The Economist Articles for Dec. 1st week : Dec. 1st(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간24.11.23조회수172 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Dec. 1st week : Dec. 1st(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | On another planet

The opportunities—and dangers—for Trump’s disrupter-in-chief

Elon Musk is given the ultimate target: America’s government

In 2017 Elon Musk branded Donald Trump a “con man” and “one of the world’s best bullshitters”. Now he is known at Mar-a-Lago as Uncle Elon and is in the president-elect’s inner circle. This week they watched a rocket launch together. The alliance of the world’s leading politician and its richest man creates a concentration of power both want to use to explosive effect: to slash bureaucracy, detonate liberal orthodoxies and deregulate in the name of growth.

Mr Trump has a mandate for such disruption. Despite America’s economic prowess, much of Main Street, Wall Street and Silicon Valley is frustrated by government profligacy and incompetence. They are right to be. The state needs an overhaul. Yet Musk-led reform risks creating a new problem for America: the emergence of a combustible, corrupt oligarchy.

Weeks after helping Mr Trump win the election Mr Musk has climbed to the apex of power. The president-elect has appointed him to a new advisory body, called doge, tasked with slashing spending. Mr Musk is already in touch with foreign leaders and lobbying for cabinet appointments. It is hardly the first time a tycoon has had extraordinary influence in America. In the 19th century robber barons such as John D. Rockefeller dominated the economy. In the early 20th century, when there was no Federal Reserve, John Pierpont Morgan acted as a one-man central bank.

Mr Musk’s firms are more global than the big 19th- and 20th-century monopolies, and smaller if measured by profits to GDP. Musk Inc is worth the equivalent of just 2% of America’s stockmarket. Its main units are Tesla, an electric-car firm; SpaceX, his satellite-communications and rocket business; X, formerly Twitter; and xAI, an artificial-intelligence startup that was valued at $50bn in a deal this week. These mostly have market shares below 30% and face real competition. The Economist reckons that 10% of Mr Musk’s $360bn personal fortune is derived from contracts and freebies from Uncle Sam, and 15% from the Chinese market, with the rest split between domestic and international customers.

Mr Musk is also different because he is a disrupter. Rather than exploiting monopolies to raise prices, or creating a stable banking system as the foundation for finance, most of Musk Inc uses technology to slash costs in competitive markets. This disruption is central to Mr Musk’s messianic ideology, in which innovation conquers humanity’s intractable challenges from climate change to colonising Mars. Realising these distant goals depends on a genius for constantly rethinking industrial processes. His desire for freer action helps explain his contempt for orthodoxies, including what he regards as woke conformism. From the bureaucrats who allowed the American government’s space-launch market to be rigged by defence firms to the Californian box-tickers who regulate Tesla’s factories, he views the state as an impediment to growth.

Both Mr Trump and Mr Musk want to disrupt the entire federal government. Mr Musk has said DOGE may aim to cut as much as $2trn from the $7trn annual federal budget and abolish many agencies. It is easy to ridicule such goals as naive—$2trn is more than the government’s entire discretionary spending. But with a budget deficit of 6% of GDP and debt of almost 100%, reform is needed. The creaking Pentagon machine is struggling to adapt to the age of drones and AI. Lobbying by incumbent firms helps explain why federal regulations have reached 90,000 pages, near an all-time high. Even if Mr Musk achieved only a fraction of his liberalisation, America could have much to gain.

What, though, are the dangers? One is cronyism and graft. The president-elect is an economic nationalist and the industries Mr Musk has interests in have become strategic, thanks to rivalry with China, the militarisation of space and cross-border disinformation wars. Proximity to power could let him skew regulations and tariffs and hobble competitors in fields from cars and cryptocurrency to autonomous vehicles and AI. Since the start of September the total value of Musk Inc’s businesses has risen by 50% to $1.4trn, far outperforming the market and its peers, as investors bet that its boss will be able to extract exceptional rents from his friendship with the president.

At the same time Mr Musk could bungle, especially when he is outside his areas of expertise. He has shown erratic judgment in foreign affairs, by micromanaging the use of the Starlink satellite service in Ukraine and comparing Taiwan’s status to Hawaii’s. His love of the limelight and conspiracies, and of the swirl of social media, are worrying. With $50bn of his personal wealth tied up in China, which hosts half of Tesla’s production, he is an obvious target for manipulation.

He could also fail before he even starts, because of the combustibility of the Trump-Musk combination. The next president loves hiring and firing. The tech tycoon burns through executives and relationships, too. The fusion of Silicon Valley libertarianism and techno-utopianism with the maga nationalism of Mr Trump’s world is inherently volatile. Reforming government requires patience and diplomacy, neither of them Mr Musk’s strong suits.

On another planet

If Mr Musk’s political career proves to be brief, it could still have two lasting, pernicious effects. One would be to turn politicians away from reforming government. With his appointment, that goal has received more attention than ever. But if he mounts a half-baked programme that ends in spectacular failure, the ambition to tackle spending will be set back for years.

The other effect would be to normalise collusion between politicians and tycoons. As the state expands into trade, industrial policy and technology, the incentives for state capture are growing. At the same time, Mr Trump’s method involves weakening institutions and practices supposed to guard against conflicts of interest. America is a long way from behaving like an emerging market. But if oligarchic business titans habitually worked with dominant politicians, it would suffer great harm. That used to be unthinkable; no longer. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

What Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders get wrong about credit cards

Forget interest rates. Rewards are the real problem

Illustration: Alvaro Bernis

Nov 21st 2024

Democrats spent much of the presidential-election campaign calling Donald Trump a fascist. Mr Trump is hardly known for his conciliatory nature. So few American politicos expect there to be much bipartisanship in his second term. Yet in one place there is already a flicker of cross-aisle agreement: a proposal to cap interest rates on credit-card repayments at 10% has won the support of both Mr Trump and Bernie Sanders, perhaps the most prominent left-wing Democrat.

Sadly, the policy is unwise. Like most price controls, capping interest rates would distort the market and hurt ordinary punters. Card issuers would probably respond by locking out less reliable borrowers, not by offering cheaper rates. Worse still, Messrs Trump and Sanders are looking past genuine problems with American credit cards. That may be because the problems stem from something stupendously popular: ultra-generous rewards.

Credit-card rewards are meagre in much of the rich world, especially Europe. But in America they are chunky, and many are hooked. The Points Guy, a website with the strapline “Maximise your travel”, which recommends strategies to accumulate and spend credit-card points, has garnered almost 30m visits in the past three months. More than 600,000 people subscribe to the r/churning forum on Reddit, a social-media site, where members construct elaborate strategies to “churn” through different cards, capitalising on introductory offers. A common piece of advice for would-be churners is to beware the “5/24 rule”. JPMorgan Chase, a bank, is thought to issue blanket denials to anyone who has signed up to five or more cards over the previous 24 months.

Options run from relatively straightforward cashback cards, which might offer 1.5% back on each transaction, to jazzier, more expensive ones. Some charge hefty annual fees: $695 for the American Express Platinum card, for instance. Customers can, in theory, recoup these with points and benefits such as credits for flights, food delivery and subscriptions. In practice, clawing back fees can be tricky and distort spending. Your columnist, desperate to spend a $50 American Express voucher for Saks Fifth Avenue, a department store, before it expired, once found himself ordering an entirely unnecessary $49 geranium-scented-soap dispenser.

To the sufficiently obsessed, optimising credit-card spending can be a lucrative hobby. However, beneath the bonanza is a problem: the rewards are funded by the least well-off. This happens in two ways. First, customers who do not use credit cards subsidise those who do. Half of all transactions by households earning more than $150,000 a year are done by card, compared with just one in ten for those earning less than $25,000. The subsidy occurs because every time a card is used, merchants are charged an interchange fee. In America that is usually around 2% of the value of the transaction, though it can easily be higher for premium cards. The fee then gets split three ways: between the credit-card company (most often Mastercard or Visa), the issuer (usually a bank) and the customer (via cashback or rewards). Each beneficiary, unsurprisingly, enjoys this arrangement: banks and credit-card companies make a tidy profit; shoppers get a little closer to funding that business-class flight to the Maldives. Merchants are rather less grateful, but they generally fold the fee into their prices—meaning those who do not use credit cards share the pain.

Merchants could, in theory, demand higher prices from credit-card users. This happens occasionally; for instance, some stores offer discounts when payments are made by cash or else only accept card payments for larger transactions. Rent payments often cannot be done by credit card, or at least not without sizeable additional fees. But until recently adding surcharges for credit-card payments was banned, both in retailers’ agreements with credit-card companies and, in some states, by legislation. In 2013 a class-action lawsuit put an end to surcharge bans by Mastercard, Visa and the like. Most state-level laws are also getting pared back. In New York credit-card surcharges were outright illegal until 2018, when the state Court of Appeals ruled that surcharges were permitted as long as they were adequately disclosed. Still, a widespread shift in pricing norms looks unlikely. Americans are too used to the current way of doing things.

A second issue is that rewards function as a tax on those with credit cards but without the ability or inclination to keep up with the panoply of options. Sumit Agarwal of the National University of Singapore, Andrea Presbitero of the IMF, and André Silva and Carlo Wix of the Federal Reserve find that American credit-card-reward programmes redistribute around $15bn a year from “naive” to “sophisticated” consumers. In cash terms, the biggest losers are actually the unsophisticated well-off. Yet financial sophistication, which the researchers approximate with credit-rating scores, also correlates with education, income and race. High-school graduates, the poor and ethnic minorities are the least likely to earn credit-card rewards.

The Brussels route

What could Mr Trump do? One answer lies on the other side of the Atlantic. In 2015 the European Union capped credit-card interchange fees at 0.3%. Research by the European Commission estimates that 70% or so of the reduction has been passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices. At the time, The Economist was sceptical of the EU’s move. Better, we thought, to let competition yank down fees than to do so by state diktat: startups could profit by undercutting incumbents. Although that is still the best solution, there is little sign of such disruption. If Mr Trump can stomach taking inspiration from Europe, and is willing to incur the ire of r/churning, he could support legislation to lower interchange fees—ideally by enough to scupper reward programmes. ■

Leaders | It’s time

Why British MPs should vote for assisted dying

A long-awaited liberal reform is in jeopardy

Nov 21st 2024

This newspaper believes in the liberal principle that people should have the right to choose the manner of their own death. So do two-thirds of Britons, who for decades have been in favour of assisted dying for those enduring unbearable suffering. And so do the citizens of many other democracies—18 jurisdictions have passed laws in the past decade.

Despite this, Westminster MPs look as if they could vote down a bill on November 29th that would introduce assisted dying into England and Wales. They would be squandering a rare chance to enrich people’s fundamental liberties.

The proposal—put forward as a private member’s bill by Kim Leadbeater, a Labour backbencher—seeks to set out the safeguards that would govern assisted dying for the terminally ill. This will be a free vote, in which MPs follow their conscience rather than a party line and Ms Leadbeater has received no help from the government, even though the prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, has said he is in favour. A few weeks ago, it looked as if her bill would pass. Now opposition is growing and Sir Keir has taken up a position on the fence.

You might think the debate over assisted dying would be about principles. But appealing to God or the sanctity of life would no longer succeed in today’s Britain. Such arguments, however sincere, operate in a space that is governed by individual conscience, not the state.

What is more, the principle of assisted dying has already been established. The courts have ruled that doctors can withdraw life support from patients in a vegetative state. And Britons are free to travel to Switzerland for an assisted death. Between 2016 and 2022, about 400 people did so.

Ms Leadbeater’s bill extends this logic. Going to Switzerland to die costs about £15,000 ($19,000); companions risk prosecution. The bill would make assisted dying open to anyone who qualifies, rich or poor, including those who need their family to be with them.

Those who can no longer defeat the bill on principle have therefore joined those who worry about the details. But these arguments do not withstand scrutiny either.

Much of the running is being made by Wes Streeting, who as health secretary has argued that access to palliative care is too hit-and-miss to give terminally ill patients a genuine choice. That is a red herring. The closest analogue to Ms Leadbeater’s proposed system is in the Australian state of Victoria, which passed its law in 2017. It gathers data on palliative care and has found that assisted dying does not happen more often in places where access is patchier.

In any case Mr Streeting could afford to improve access to palliative care. Those in the hospice sector in England believe that an extra £350m-400m of annual statutory funding, around 0.2% of the nhs budget, would allow them to meet demand fully. Even then, the need for assisted dying would remain. One reason is that in around 1% of cases, the best palliative care does not ease physical pain; another is that most people choose assisted dying because they want autonomy.

In a bold piece of ministerial judo, Mr Streeting also argues that the health service, which he runs, is too broken to take on the burden of assisted dying. Yet doctors already routinely make decisions over life and death. Through the principle of “double effect”, doctors can administer painkillers to terminal patients knowing that they will cause death. One salutary consequence of Ms Leadbeater’s bill would be to bring these obscure judgments into the light, and to involve patients in them.

Critics also raise concerns about the risk of coercion. But that is not credible in this case. In Ms Leadbeater’s bill a person with around six months to live must make sustained requests approved by two doctors and a judge. The idea that an evil relative might go to great lengths to kill someone who will shortly be dead makes no sense.

Someone may choose an assisted death for fear of being a burden, which is cited as a reason in four out of ten cases in Oregon, which has had an assisted-dying law for longest. It would be better if people didn’t feel burdensome, obviously, but that does not stop them from making rational choices. Indeed, the option to die may be all the comfort people seek: a fifth of those handed the medication in Victoria never take it.

Even if opponents of the bill are reassured by these arguments, some cannot shake the fear that Ms Leadbeater’s law would be a slippery slope. If they mean that the criteria would sneakily be broadened to include the mentally ill or disabled without further legislation, then the facts are against them. In no case has an assisted-dying law restricted to the terminally ill expanded in this way. In Canada the scope widened, but that was because the courts enforced broad eligibility criteria derived from the country’s existing Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

If they mean that future legislation could extend the right to assisted dying after due debate and consideration, then that is not an argument against, but a recommendation. In the view of The Economist, Ms Leadbeater’s bill is drawn too tightly. Oregon and Victoria have shown that a doctor does not need to be present for the medication to be safe. A High Court judge is unnecessary when two doctors have already given their opinions. A prognosis of six months or less to live is arbitrary and imprecise. A 21-day cooling-off period is too long for people with only a very limited time to live; in 2021 California reduced this period from 15 days to two. None of that is an argument for voting down the current bill—indeed it can improve as it passes through Parliament.

Ms Leadbeater’s bill would have been better if the government had helped her prepare it, or if Sir Keir had set up a citizens’ assembly that weighed up the evidence and presented MPs with an agenda. The fact that he did not is one more example of his passive style of government. But that is not a reason to reject it, either. We would sooner that more Britons benefit from greater freedom, choice and dignity than none does. MPs should reassure themselves about the details of the bill, and then they should vote for it. ■

Leaders | Diminishing returns

Too many master’s courses are expensive and flaky

Governments should help postgraduates get a better deal

Illustration: Travis Constantine

Nov 21st 2024

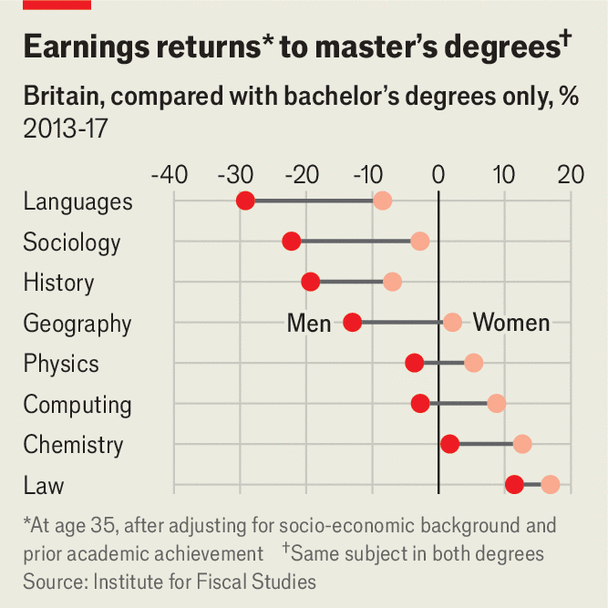

For young people with big ambitions, bagging a measly bachelor’s degree no longer seems enough. Students in America have been rushing into postgraduate courses, even as demand for higher education among the general public has declined. These days nearly 40% of university-educated Americans boast at least two degrees. In Britain a surge in demand from foreign students has created a huge boom in postgraduate education. Universities there now dole out four postgraduate qualifications for every five undergraduate ones.

Master’s degrees lasting one or two years are the biggest draw. These courses are necessary for jobs, such as teaching in academia, that are appealing even if poorly paid. Yet many of the people who enroll in postgraduate study are taking part in an educational arms race. Now that undergraduate degrees are common, goes the thinking, it takes extra credentials to get ahead. The hope is that advanced qualifications will boost all manner of careers.

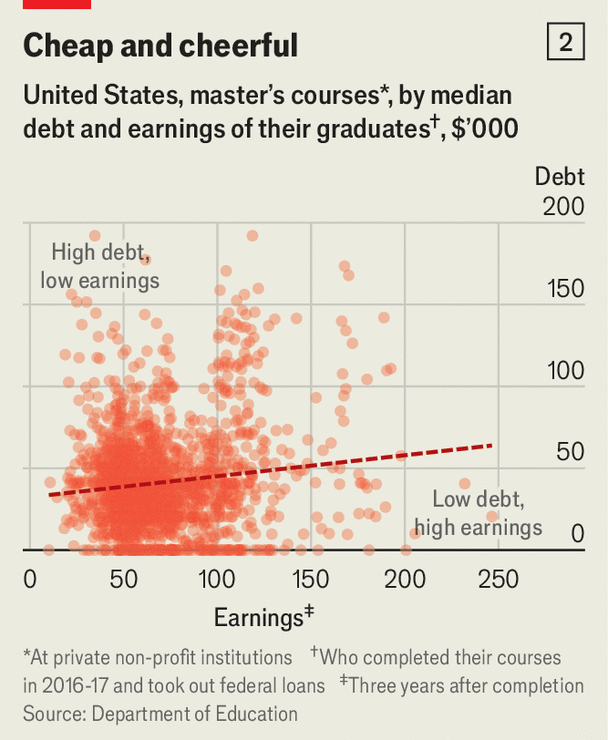

Chart: The Economist

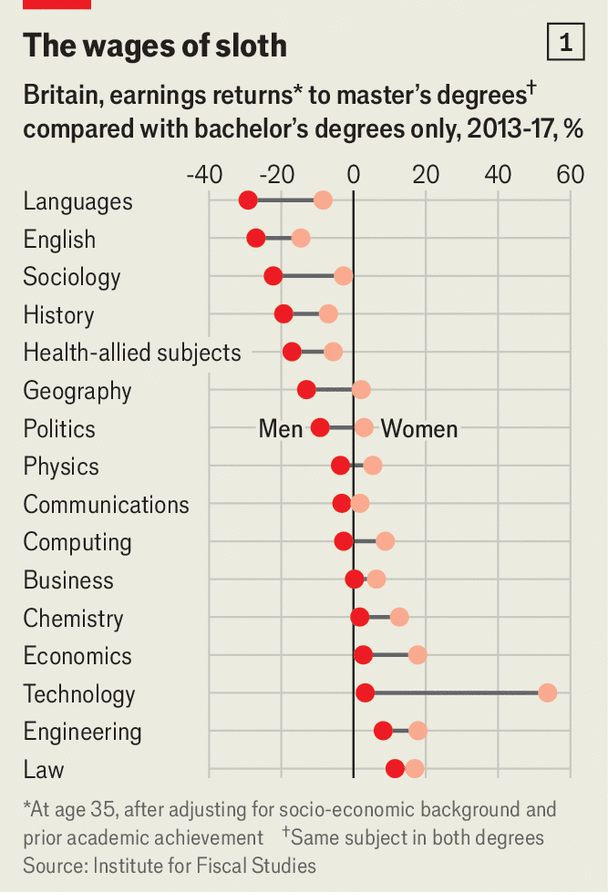

That is often a mistake. New data are helping researchers compare the earnings of postgraduates with those of peers who are equally bright but have only a bachelor’s degree. One analysis suggests that more than 40% of America’s master’s courses provide graduates with no financial return or leave them worse off, after considering costs and what they might have earned anyway. A study in Britain concludes that completing a master’s has, on average, almost no effect on earnings by the time graduates are 35.

Dreadful returns to lofty qualifications should worry students and politicians alike. Governments are right to think that investing in skills can pep up growth—but not when universities are flabby and inefficient. It is not just students who suffer if poor courses burden them with outrageous debts; taxpayers do, too. About half the money the American government lends to students each year is for postgraduate degrees. Generous repayment and forgiveness schemes mean a big chunk of that will never be repaid.

Governments should respond in two ways. First, they should abandon policies that are distorting the market for postgraduate study. America does not limit what it will lend postgraduates for tuition fees. This blank cheque has created a culture of profligacy in which universities raise fees, obliterating the financial returns students might ultimately make. Britain has also slipped up, though in a different and sneaky way. For a decade it has mostly declined to let universities increase fees for undergraduates, even as inflation has caused their costs to rise. In order to make up for that financial shortfall, vice-chancellors have vastly expanded expensive postgraduate programmes, some of which are of dubious quality.

The second priority for governments should be to give students the data they need to make better choices. A chasm divides the riches that flow from getting the most lucrative master’s, such as in computer science, from the meagre returns of English or film studies. Fees vary wildly by institution, even for very similar programmes. And yet people shopping for postgraduate education find it much harder to get hold of information—on matters such as drop-out rates or probable future earnings—than people applying for their first degrees.

Masterstroke

America is trying to change this. Under new rules, graduate colleges may soon be compelled to warn applicants before they sign up for courses that have a record of saddling students with low wages and high debts. Donald Trump, who likes to lambast college presidents, should make sure these changes take place. And regulators in other countries should consider similar schemes. Higher education ought to make students brainier and richer. It too often fails to do either. ■

By Invitation | Britain’s end-of-life debate

My assisted-dying bill safely solves a grave injustice, says Kim Leadbeater

One of a pair of essays in which members of Parliament argue their cases

Illustration: Dan Williams

Nov 21st 2024

MEMBERS OF BRITAIN’S Parliament will soon get their first opportunity in almost a decade to vote on extending the choices available to terminally ill people at the end of their lives. The second-reading debate on November 29th is an important occasion, although it will be far from the last word on the matter.

If my bill passes, it will be scrutinised by a representative committee of MPs, followed by detailed debates in both parliamentary houses, the Commons and the Lords. It is open to amendment and will only become law if both houses approve it.

If the bill is rejected, however, it is unlikely to be considered again for many years. The government maintains that it is for Parliament to decide through a private members’ bill, so there is no prospect of government ministers proposing their own bill. And if this law—widely acknowledged as the most thorough, well-drafted and safest piece of legislation on the subject ever debated in Parliament—should fail, no other MP is likely to have any prospect of success.

So the choice before MPs is between continuing the debate on my bill, with all the protections and safeguards it contains, or agreeing that the status quo is acceptable—and with it, in the words of the prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, “an injustice…trapped within our current arrangement”.

That injustice, which Sir Keir identified when he was director of public prosecutions (DPP) and voted to change when first elected as an MP, is profound. The 1961 Suicide Act makes it a criminal offence punishable by up to 14 years in prison to assist another person in taking their own life. Sir Keir, as DPP, issued guidance that there should be a presumption against prosecution when assistance was given purely on compassionate grounds. But he said, and I agree, that it is for Parliament, not prosecutors, to resolve the injustice.

I have heard so many heartbreaking stories from individuals and families affected by the current law. It is those voices that I have been encouraging MPs to listen to above all others, and not just the voices of those whose loved ones suffered an agonising death despite receiving the best palliative care. Although those accounts are particularly distressing, there are also the many husbands, wives, partners and children who have had to wave goodbye as a terminally ill person goes abroad, if they can afford it, to die alone. Or those who have had to deal with the trauma of a suicide by someone who felt they had no choice but to take matters into their own hands. In most cases these deaths take place before a person is ready to go, because they need to be well enough to act. They are denied the comfort of a final goodbye surrounded by love and support, and those left behind must add feelings of guilt and anguish to their grieving.

So the status quo is indefensible. My job has been to propose an alternative that addresses these injustices, offers the strongest possible protections and safeguards for a person seeking assistance to shorten their death, and is workable for the medical profession and the judiciary in particular.

We can learn from what has worked well in other jurisdictions and also see where things have gone in a direction we would not wish to follow. Under my bill no one would be eligible for assistance because they were disabled or mentally ill, or had an eating disorder, depression or anything other than a terminal illness. The courts, both domestic and European, have made clear that if Parliament votes for my very restrictive legislation, they would not and could not broaden its scope as has happened in Canada and elsewhere.

At every stage, a person requesting assistance must have a clear, settled and informed wish to end their life. Periods of reflection mean the process cannot be rushed and they can change their mind at any time. Two independent doctors and a High Court judge must be satisfied that a patient is eligible under the legislation, is mentally competent to express their decision and has not been coerced. I have had lengthy discussions with the British Medical Association, individual doctors and the judiciary at the highest level. They have reassured me that medical practitioners and judges are experienced in detecting coercive and abusive behaviour in difficult, even life-and-death circumstances.

This is not about ending a person’s life but allowing them to shorten their deaths. My bill would not create a new cohort of patients: those eligible will be in the last months of their lives and already receiving care and medication. Fears of a significant extra burden on National Health Service resources are unfounded. Nor would it detract from the provision of palliative care. The opposite is the case. The parliamentary Health and Social Care Select Committee found that elsewhere in the world, palliative care improved alongside the introduction of assisted dying. Here at home I am delighted that the debate around my bill has already renewed attention on palliative care and the hospice sector. We have started talking about death, something we have historically avoided. So I hope MPs will conclude that offering the possibility of a good death is a compassionate, just and ethical decision that rights serious wrongs and brings comfort to many of our fellow citizens—whether or not they elect to exercise that choice.■

By Invitation | Britain’s end-of-life debate

Assisted-dying advocates’ claims of freedom have it backward, says Danny Kruger

One of a pair of essays in which members of Parliament argue their cases

Illustration: Dan Williams

Nov 21st 2024

WHAT IS THE purpose of the campaign to give people the right to summon the state to kill them? The answers campaigners give are dignity and choice. Note that these are not in themselves related to the condition of dying—to the practical realities of pain, fear and the emotions that assail a person as they contemplate their own end. These are meta-objects, higher goods which transcend the immediate circumstances of a deathbed. They reflect a religious idea about what it is to be human. To be human, according to this faith, is to be in control. The end, the object, is power.

The practical problems with the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill are stark and inescapable. The proposed law would require doctors and judges—both are needed, in a reflection of the fact that neither is really competent to do so—to confirm that a patient may reasonably be expected to die within six months, and that he or she genuinely and freely wishes to die.

As we see in places where assisted dying happens, however, all this means is that someone with a chronic condition can refuse their drugs, or an anorexic can refuse their food, and a doctor will be found to confirm that their condition is terminal. We are all within six months of death if we choose to be.

If our only object were—as it should be—to relieve suffering at the end of life, to address the practical realities of death, there is a simple solution: to properly resource palliative care. Modern pain-relief drugs mean almost no one needs to die in unbearable physical agony. Everyone can be helped to die well, but end-of-life care at the moment is patchy and shamefully underfunded.

But the campaign is not about these things. Indeed, a subset of campaigners is open in declaring this bill as merely the beginning, and that once the right-to-die principle is established access to it will soon be widened—as has happened in other jurisdictions that have started down this road. The idea that animates the bill is that of absolute patient autonomy.

Yet the crucial paradox is that it will have precisely the opposite effect. A religion of individual control, of personal freedom, is not liberating in practice, but rather deeply disempowering. There remain Labour members of Parliament who remember that “progressive” politics used to be about protecting the vulnerable from abuses of power—that individual autonomy is not the highest good, because different people have different degrees of agency and in a liberal free-for-all the powerless get trampled.

Under the bill, doctors will be allowed to suggest assisted dying to patients who have not mentioned the idea themselves. If the patient requests it from a doctor who does not agree with the practice, that doctor will be obliged to refer them to a colleague who does. Here we see the dynamic established: this is presented as a plausible, even a good choice for patients to make, and the system will help them to make it. The echoes of the Liverpool Care Pathway, a notorious scheme of ten years ago by which patients were essentially assigned by the National Health Service to die, should sound in our ears.

The law’s very existence would put pressure on each patient and their family to have “the conversation”, whether openly at the bedside or whispered outside the room: is it time for Mum or Dad to die? Patients would bear the awful responsibility of deciding whether to go now—sparing their loved ones the cost and distress of caring for them—or to hold on selfishly, messily, expensively.

This is not freedom. It is not autonomy. It is a terrible burden to place on people at their most vulnerable. It is not “choice” when one option is so total and potentially compelling. It speaks of a profound disrespect for the frail, and raises over the disabled a spectre that haunts them: the awareness that others might think them better off dead.

The dignity that we need at the end of life is to be fully cared for as we die. There is no disgrace in dependence or being a “burden” to others. And the choice we need is that over our care, including using advanced health-care directives to provide clear wishes on being resuscitated or kept alive if we were to lose cognition or the ability to communicate.

Not for nothing do campaigners for assisted dying call it “the last right”. For this is the unintended object of the theology of control. Cross this Rubicon and, as with Julius Caesar, the republic of liberty falls. In the name of progress we will obliterate the key protection which all of us have need of as we grow old and ill and burdensome: that the people at our bedside will not connive to kill us.■

Briefing | Poster boy

Elon Musk’s transformation, in his own words

Our analysis of 38,000 posts on X reveal a changed man

Photograph: Getty Images

Nov 21st 2024

“Sure, you might say something silly once in a while, as I do, but that way people know it’s really you!” As part of a plea for “political & company leaders” to join him in holding forth on X, his social network, Elon Musk has repeatedly stressed that such posts offer an unusual and engaging authenticity. We have taken him at his word. What do his tweets say about him?

Chart: The Economist

To work out what subjects preoccupy Mr Musk and how his views have changed over time, The Economist analysed his activity on Twitter (as it was) and X (as it became in 2023). Using artificial intelligence to trawl through his 38,358 posts between December 2013 and November 2024, we found that he is posting far more often and with a far more political bent. Climate change and clean energy used to be the realm of policy on which he opined the most, but he now bangs on much more about immigration and free speech (see chart 1).

Mr Musk posts vastly more than he used to. From December 2013 to the middle of 2018, he tweeted just over a dozen times a week, on average. Between then and October 27th 2022, when he completed the purchase of X, he was posting 50 times a week. Since the takeover, that has risen to around 220 a week.

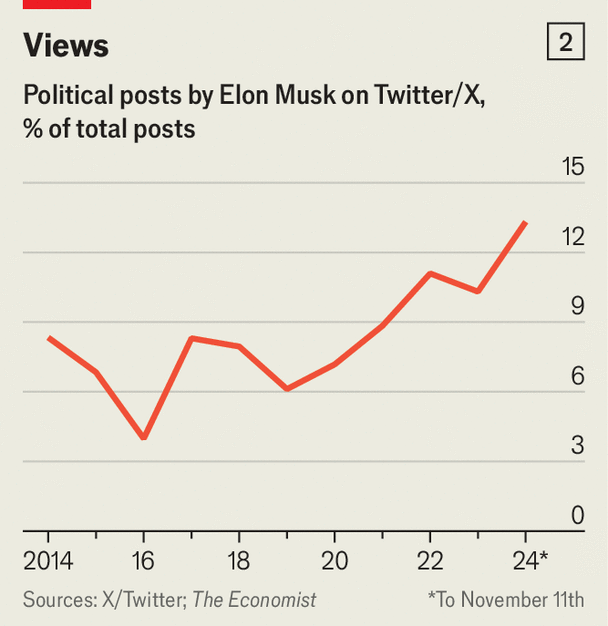

Those who follow him—and over 200m do—may also have noticed a shift in subject-matter. From 2016 to 2021 between 30% and 50% of his tweets each year were about Tesla or SpaceX, his two biggest companies. These days only 11% are. Meanwhile the share of his posts that are political has risen from less than 4% in 2016 to over 13% this year (see chart 2).

Chart: The Economist

The shift in the topics of such posts is even more dramatic. In 2022, as he was buying Twitter, posts about free speech surged. This was followed by a leap in 2023 and 2024 in talk of immigration, border control, the integrity of elections and the “woke mind virus”. (The vicissitudes of poor regulation has remained a common topic throughout.)

Despite his considerable business interests outside America, few posts mention other countries. Between 2017 and 2020 around 1% touched on China, but often in passing (“China & Japan have awesome trains…”) or to praise Tesla’s unit there. His interest in the country has since waned. Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Mr Musk showed little interest in either country, but in 2022 they featured in almost 3% of his tweets. The only other country to crop up in more than 1% of his posts in recent years is Brazil, after the country briefly blocked X in August this year.

To his followers Mr Musk advocates a fierce focus on missions he sees as urgent, such as making humans an “interplanetary species” by colonising Mars. But his own posts reveal shifting interests over the past few years, with the only truly intense focus on the act of posting itself. He may have more money than anyone else on Earth and the ear of the next president, but to a casual observer, he may not seem that different from any other American man in his 50s: lurching rightward politically, online a huge share of the time, complaining about immigration and mocking the left.■

United States | Farewell to the five queens

Los Angeles decides it is sick of scandal

A county of 10m people conducts a civilised revolution

The ancien regimePhotograph: Christina House/Los Angeles Times via Contour RA

Nov 19th 2024|Los Angeles

LESS NOTICED among recent political events, Los Angeles is reckoning with a small revolution. Los Angeles County is home to nearly 10m people, making it more populous than all but ten states. Its five supervisors wield a $50bn budget. What happens in this sprawling conglomeration of suburbs and highways affects a quarter of all Californians. And, as in the rest of the country, Angelenos voted for change.

In contrast to many Midwestern and east-coast population centres, county governments in California are run by five supervisors, who combine executive, legislative and quasi-judicial powers. In LA “each supervisor is an autocrat in their district”, says Fernando Guerra, director of the Centre for the Study of LA at Loyola Marymount University. That is about to end.

Voters narrowly chose to expand the board of supervisors to nine, elect (rather than appoint) a county chief executive and create an ethics commission to increase oversight of the whole shebang. The measure’s passage marks the first time voters have approved board expansion since 1913, when the county adopted its charter and its population hovered somewhere near 500,000. In the city of Los Angeles, which is run by a mayor and a powerful city council, voters favoured ballot measures to implement independent redistricting of the council and school board, as well as to strengthen the city’s ethics commission. The sum of these results is a repudiation of the corrupt and ineffective politics that has dogged Los Angeles in recent years.

The decisions to overhaul the structure of local government are largely a reaction to a series of scandals. Four former or sitting city-council members have faced criminal charges in as many years for embezzlement, bribery or lying to the feds. In 2022 a leaked recording of three other council members and a labour leader revealed the group of Hispanic powerbrokers making disparaging remarks about other ethnic groups as they discussed how to slice up the city during redistricting. Three of the four lost their jobs, and the final holdout lost his bid for re-election.

Their ousting did not placate Angelenos. The ballot measure that will create an independent redistricting commission is meant to combat the kind of back-room politicking caught on tape. For structural reform to happen “there usually has to be something…that has really got people agitated”, says Raphael Sonenshein of the Haynes Foundation, which supports research on governance and democracy in Los Angeles. The last time LA saw such a reckoning was in the 1990s, when the Rodney King riots prompted police reform, among other efforts.

What will the county’s measure achieve? The five supervisors are known as the “five little queens”. Their fiefs of roughly 2m constituents each will be nearly halved in size when four new colleagues join the board in 2032, after the next census reapportionment. Governance wonks hope that budgets will be better allocated for homelessness and that supervisors will be more responsible to their voters. “Local government works best when…elected officials have to pay attention to their constituents,” says Mr Guerra. “When districts get too big, that just cannot happen.”

Zev Yaroslavsky sat on the county board for 20 years, and the city council for 20 years before that. He argues that the most consequential reform is actually the creation of an elected county chief executive. He likens LA County’s government to a business without a CEO or a state without a governor. The county’s size and wealth demand a different system, he reckons, and a leader that can take decisive action rather than dithering. The person who is elected to that position will be among the most important—if not the most important—local-government executives in the biggest state in America, he argues.

Many bits of the reform have yet to be finalised, including how exactly the county will pay for the new positions (taxes have been ruled out). Mr Yaroslavsky relishes those details, while knowing that they will make others’ eyes glaze over. “Governance makes a difference,” he says, even if “it’s boring as hell”.■

United States | Fries with that

How gaga is MAHA?

RFK junior, Dr Oz and co. have the potential to do harm, but also some good

Fly-thruPhotograph: Donald Trump Jr

Nov 20th 2024|WASHINGTON, DC

When Michelle Obama suggested in 2010 that American children should eat less junk food, it triggered outrage in conservative circles. “Get your damn hands off my fries, lady,” Glenn Beck, then a Fox anchor, told his audience, adding that “if I want to be a fat-fat fatty and shovel French fries all day long, that is my choice.” Right-wing commentators criticised “food-police” overreach. Within months of Donald Trump becoming president in 2017, his administration said it would roll back some of the healthy school-lunch requirements (it failed).

The idea that Americans should be free to eat whatever they want, that the government has no business in their fridges, and that companies should be able to make money with as few regulatory hurdles as possible, has long been core to Republicanism. But “make America healthy again” (MAHA), championed by Robert F. Kennedy junior, Donald Trump’s pick for secretary of health, challenges these orthodoxies. Indeed, his merry band of followers is anything but orthodox. The latest to join is Dr Mehmet Oz, a star known for promoting pseudoscience and having psychics on his tv show, who has been nominated to lead the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which provides health coverage for nearly half of Americans.

If confirmed, Mr Kennedy will be responsible for leading 13 agencies, including CMS, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). He would be in charge of managing national health crises, from the current opioid epidemic to a future pandemic, and will have power to direct the agencies’ priorities. Putting a vaccine-sceptic conspiracy theorist in charge of the country’s health policy, and the largest department in terms of federal budget, is nutty. Yet underneath the tinfoil hat Mr Kennedy—who calls ultra-processed foods “poison” and waxes lyrical about regenerative farming—advocates some things liberals have long favoured.

In a video promoting MAHA, Mr Kennedy promised that he and Mr Trump would “transform our nation’s food, fitness, air, water, soil and medicine”. To achieve this, he has pledged to replace “corrupt industry-captured officials” in the health agencies with “honest public servants”, take a tough approach with big business, use government regulation to ban harmful substances from food and farming, and support alternative medicine.

MAHA supports interventions which under a Democratic administration would be termed “nanny state”. Mr Kennedy wants to ban pharmaceutical advertisements and has promised to “get [ultra-] processed food out of school lunch immediately.” Calley Means, a rising star in the MAHA movement, recently said that “Michelle Obama was right,” in her efforts to make school lunches healthier. Where most Republicans ridiculed Joe Biden’s efforts to insist on clearer food labels, Mr Kennedy wants much the same.

The MAHA agenda is outspokenly hostile to big business and Mr Kennedy—a former environmental lawyer who successfully sued corporations for using harmful chemicals—makes no secret of his plans to go after Big Pharma, Food and Agriculture. He advocates stricter regulation and has said he wants to eliminate “1,000 ingredients in our food that are banned in Europe”. Although it seems unlikely Mr Trump read the small print on Mr Kennedy, he has (for now) endorsed his criticisms of industry, writing in his nomination announcement that “For too long, Americans have been crushed by the industrial food complex and drug companies.”

The third and final area where MAHA looks less like traditional conservatism and more like hippy progressivism is in its embrace of alternative medicine and unorthodox approaches to health. Mr Kennedy advocates bringing a range of experimental treatments into the mainstream. He has berated the FDA for “suppressing” alternative therapies, from the kooky to the dangerous, and has suggested Medicaid should cover health food and gym memberships. He wants half of the National Institutes of Health’s research budget to be spent on “preventive, alternative and holistic” treatments. And he wants to legalise psychedelics for therapeutic use—a departure for the party of “Just say no”.

Ultimately, Mr Kennedy will be able to act only at the behest of his boss who, having promised to let the bear-botherer “go wild”, has also sent a few mixed signals about his commitment to MAHA. In a picture posted last weekend by his son, Donald Trump junior, Mr Trump and Mr Kennedy posed with McDonald’s meals and Coca-Cola. The accompanying text read “Make America Healthy Again starts TOMORROW.” It did not look like a happy meal for Mr Kennedy. ■

The Americas | A match made in the Middle Kingdom

Brazil courts China as its Musk feud erupts again

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, spies a chance to draw Brazil closer

Photograph: Getty Images

Nov 17th 2024|São Paulo

The re-election of Donald Trump on November 5th rather overshadowed Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s big bash. Lula, as Brazil’s president is known, hosted the G20 leaders’ summit in Rio de Janeiro on November 18th and 19th. Heads of state from 19 of the world’s largest economies, as well as the European and African Unions, convened to talk shop.

Lula had three goals for the summit: the creation of a global alliance to reduce hunger and poverty; an agreement to reform global institutions like the IMF and the UN; and an increase in countries’ financial commitments to combat climate change. He also wanted to whip up support for a global tax on billionaires. Lula got a declaration signed by all g20 participants to broadly support these ambitions. Mr Trump, soon to be the most powerful person in the world, will not share the zeal.

Mr Trump’s return to the world stage may scupper Lula’s plans, but he has a consolation prize: his relationship with Xi Jinping. After the g20 China’s president travelled to Brasília, the capital, to meet his Brazilian counterpart. To celebrate 50 years since their countries established diplomatic ties they signed 37 agreements, covering everything from Brazilian grape exports to co-operation on satellites. Sino-Brazilian relations “are at their best moment in history,” said Mr Xi, with Lula by his side. In recent months, “anyone who is anyone in Brazil has been to China,” says a former Brazilian ambassador to Beijing.

Several factors have been pushing Brazil and China together. In Brazil’s case they are mostly political. Shortly before the election in the United States, Lula threw veiled support behind Kamala Harris, Mr Trump’s rival. Meanwhile, Mr Trump is close to Jair Bolsonaro, Lula’s far-right populist predecessor and nemesis. Elon Musk has become Mr Trump’s right-hand billionaire. The tech entrepreneur had a months-long feud with Brazil’s highest court this year, which culminated in his social-media platform, X, being banned in Brazil for over a month. On November 16th Lula’s wife, Rosangela da Silva, said “Fuck you, Elon Musk,” at a public event. Mr Musk replied on X, “They are going to lose the next election”. This means Lula will not expect a warm reception in Washington after Mr Trump is inaugurated in January.

China’s problems with the United States run deeper. Mr Trump has said he will slap 60% tariffs on all Chinese goods as soon as he takes office. And so China is keen to do everything it can to expand the markets for its goods beyond the United States. Brazil, the world’s ninth-largest economy, is an important part of that puzzle. Brazil also shares China’s multipolar view of the world, and is keen to rely less on the dollar for international transactions.

But perhaps the most important component of Sino-Brazilian friendliness is that China wants to buy what Brazil is selling. China guzzled Brazilian oil, iron ore and soyabeans though the 2000s as the Chinese middle class grew rapidly. It overtook the United States as Brazil’s biggest trade partner in 2009, during Lula’s second term (see chart). Commerce continues to expand despite slowing Chinese growth. Brazilian exports to China are running at record highs. Brazil is one of a handful of countries that boast a trade surplus with China; last year it exported $51bn more to the Asian giant than it imported from it.

Chart: The Economist

And that surplus could yet grow. During Mr Trump’s last term, between 2017 and 2021, Brazilian exports to China nearly doubled as China bought soyabeans, corn and chicken from Brazil instead of the United States. On this visit, Mr Xi and Lula signed deals that could soon allow Brazil to export grapes, sesame, sorghum and fish products to China, which could be worth a combined $450m per year. TS Lombard, an investment firm in London, reckons that a 10% increase in Chinese demand for Brazilian products could boost GDP growth from a projected 2% in 2025 to 2.6%.

But it is Chinese investment in technology, industry and green energy which most excites Lula, a former carworker who has pledged to slash Brazil’s carbon emissions. The United States remains the biggest source of foreign investment into Brazil by far. Chinese investment in the region—and in Brazil—has fallen in recent years. But the composition of that investment still suits Lula. Last year fully 72% of it went to clean-energy projects. Exports of electric vehicles, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries from China to Latin America rose from $3.2bn in 2019 to $9bn in 2023. Brazil absorbed 63% of the total by value.

“Five years ago China was investing in expensive fixed assets like electricity infrastructure, oil and gas,” says Hsia Hua Sheng, a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo who also works for Bank of China. “Today it invests in manufacturing, renewables, services and logistics.” He claims that these are “higher-quality” investments because they often involve partnerships with local firms, job creation and technology transfer. BYD and Great Wall Motors, two Chinese rivals to Tesla, are opening electric-vehicle factories in Brazil next year. BYD’s is in a former Ford factory. It will be the firm’s biggest factory outside Asia.

A high-tech Chinese factory built on the site of a fading American industrial champion is hard enough for officials in Washington to stomach. But no subject is likely to ruffle as many feathers in a Trump-Musk White House as a deal on satellites. During Mr Xi’s visit a memorandum of understanding was signed between Brazil’s state telecommunications company, Telebras, and SpaceSail, a Chinese maker of low-Earth orbit satellites that competes with Mr Musk’s Starlink. Brazil’s communications minister, Juscelino Filho, said he hoped SpaceSail will offer its services in Brazil “as soon as possible”. In October, Mr Filho had visited SpaceSail’s headquarters in Shanghai and those of another satellite-maker in Beijing. The visit followed a spat about free speech and disinformation between Mr Musk and Alexandre de Moraes, a powerful judge on Brazil’s Supreme Court. In August Mr Moraes froze Starlink’s bank accounts in Brazil to force Mr Musk to take down social-media accounts on X, the platform he owns. Starlink controls almost half of the market for satellite-internet services in Brazil. SpaceSail plans to have 600 satellites in orbit by the end of 2025—around a tenth of the number that Starlink does.

Beyond this, Lula and Mr Xi could further their countries’ financial co-operation. In 2023 they agreed to settle all trade in their countries’ own currencies rather than in dollars. In October that same year they carried out the first transaction in yuan and reais. The scale of these transactions is currently puny, but they carry symbolic weight and may provoke Mr Trump’s ire. He has warned that he would slap tariffs of 100% on goods imported from countries that try to “leave the dollar”.

Such radical actions by Mr Trump would probably have unintended consequences. “The relationship between Brazilian and Chinese businessmen is way more consolidated today compared with five or ten years ago,” says Mr Hsia. That is thanks in part to the trade war Mr Trump waged in his first term. In his second, he may end up making Chinese and Brazilian businessmen friendlier than ever. ■

Asia | Banyan

Once a free-market pioneer, Sri Lanka takes a leap to the left

A new president with Marxist roots now dominates parliament too

Illustration: Lan Truong

Nov 21st 2024

Sri Lanka was once a pioneer of free-market capitalism in South Asia. After J.R. Jayewardene took power with a super-majority in 1977, he introduced a French-style executive presidency and economic reforms that overturned the left-wing orthodoxy of the previous two decades. Cheered on by Western governments concerned about Soviet influence, Sri Lanka became the first country in the region to liberalise its economy.

South Asia’s most developed nation has now leapt back to the left. It was surprising enough that Anura Kumara Dissanayake, an outlier from a party with Marxist roots, won a presidential election on September 21st. More stunning still was his National People’s Power (NPP) coalition’s landslide victory in a parliamentary poll on November 14th. It won 159 of 225 seats, more than enough to change the constitution. Previously, the NPP had just three.

Mr Dissanayake’s mandate is another clear warning to South Asia’s political and business elites in 2024, following electoral upsets in Pakistan and India and a student-led revolution in Bangladesh. Considering his Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) party’s past links to China, his victory could intensify that country’s tussle with India for influence in the region. It is also a test for the International Monetary Fund (imf), given his pledge to review a bail-out.

But the outcome raises questions for Mr Dissanayake too. What exactly does “Comrade President” (as he was introduced at rallies) plan to do with his vast powers and how will ideology shape those plans? Can he meet voters’ high expectations within the IMF’s constraints? And how open to criticism and political opposition will he be if public support wanes?

His campaigns were based on broad promises to end endemic corruption and cronyism. That proved hugely effective among voters still reeling from Sri Lanka’s first debt default, in 2022. Mass protests ousted the president that year, and though his successor stabilised the economy and secured a $2.9bn IMF bail-out, voters penalised him in September over continuing corruption and austerity measures.

Opponents portrayed Mr Dissanayake as a dangerous radical. They cited the JVP’s two failed uprisings in the 1970s and 1980s (the party renounced violence in 1994). They pointed to his paltry government experience—he was briefly an agriculture minister two decades ago. And they said he would cause a financial crisis by trying to renegotiate the IMF bail-out.

So far, such warnings have been unwarranted: Mr Dissanayake has been far more of a pragmatist than a revolutionary. As he often boasted in election rallies, he has run the country with a cabinet of just three for almost two months without spooking markets. Harini Amarasuriya, the prime minister whom he reappointed on November 18th, is widely respected. And the cabinet of 21 people he named after this month’s election includes a sensible balance of academics, seasoned politicians and new faces.

His handling of the IMF has been especially telling. While it may be possible to adjust tax rates and other parts of the existing plan for meeting bail-out benchmarks, some feared that he would demand much more, potentially re-opening debt-restructuring talks with creditors, including India and China. But in a meeting with an IMF team that arrived in Sri Lanka on November 17th, Mr Dissanayake committed to the existing agreement, according to people familiar with the discussions. “That question is at least resolved in the short term and that is important for the stability of the economy,” said one.

At the same time, in a nod to the public pressure he faces to increase social spending, Mr Dissanayake urged the IMF to maintain a “balanced approach that considers the hardships faced by citizens”. And his government did not provide details on longer-term questions, such as its growth strategy and its views on trade or the role of the state sector. “That’s where you will have an ideological issue,” predicts Murtaza Jafferjee of Advocata Institute, a think-tank in Colombo, the capital. He fears that the government’s protectionist and statist instincts could stifle badly needed productivity growth.

Some answers may become clearer in the next few weeks, when Mr Dissanayake is expected to present an interim budget. Not all Sri Lankans may like what they hear. For the moment, though, most are just glad to be rid of a political old guard that pushed their once promising economy to the brink of collapse. ■

China | The Sino-American rivalry

Helping America’s hawks get inside the head of Xi Jinping

China’s leader is a risk-taker. How far will he go in confronting America?

Illustration: Ellie Foreman-Peck/Getty Images

Nov 21st 2024

AS DONALD TRUMP assembles his foreign-policy team, many of his picks display a common characteristic: they are strident China hawks. Those seeking a tougher approach towards America’s rival range from Mike Waltz, Mr Trump’s proposed national security adviser, to Marco Rubio, his nominee for secretary of state. Part of their job will be to grasp how relations have changed in the four years since the last Trump administration, a period in which the Chinese economy has sagged, tensions around Taiwan and in the South China Sea have grown, and the war in Ukraine has further divided the world’s biggest powers. When weighing up the risks Xi Jinping is prepared to take in his competition with America, new calculations are needed. Forming them must involve studying what motivates China’s leader.

A valuable tool is the vast body of literature purporting to have been written by Mr Xi. The number of volumes bearing his name, explaining his views on China’s main concerns at home and abroad, far exceeds that of books by Mr Trump or Mr Putin—or, indeed, previous Chinese leaders (see chart). According to an estimate by the China Media Project, he published 120 volumes in the first decade of his rule. This year at least nine have been added to the pile (“Excerpts from Xi Jinping’s Discourses on Natural Resources Work” is hot off the presses this month).

Chart: The Economist

These books are tedious, but they are also important. They reflect the ideology that guides the party and show how Mr Xi is trying to reshape it to justify his distinctive approach to ruling the country and projecting Chinese power. In 2017, during Mr Trump’s first term, “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” by François Bougon, a French journalist, became the first critical book-length study of what is commonly known as “Xi Jinping Thought”. Mr Bougon argued that Mr Xi “manoeuvres, tinkers, and seeks his balance” between conflicting ideological forces in China. “There is no indication that he is the author of a coherent doctrine of his own.”

Analysts now have much more of Mr Xi’s thought to sift through. Among global statesmen, Kevin Rudd is rare in having undertaken this task. Mr Rudd was Australia’s prime minister between 2007 and 2010, when Mr Xi was China’s heir apparent, and again in 2013, after Mr Xi became leader. In a recent book, “On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World”, Mr Rudd, who is now his country’s ambassador to America, says “the outline of Xi’s brave new world is now hiding in plain sight for us all.” His bibliography lists well over 50 of Mr Xi’s books. More than a quarter were published after Mr Trump left the White House.

In Mr Rudd’s telling, ideology is the main impulse behind Mr Xi’s actions. China’s leader sees powerful historical forces leading to the decline of the West and the ineluctable rise of the East. The process can be hastened by a disciplined Communist Party that understands the dialectical process. In his pursuit of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by 2049, when the party marks the centenary of its rule, a defining objective is “reunification” with Taiwan. Like his predecessors, Mr Xi does not rule out the use of force.

Mr Xi has steered China towards what Mr Rudd calls Marxist Nationalism. In other words, he has purged the party and strengthened its control, shifted economic policy away from market forces towards greater central planning, and embarked on a more bellicose foreign policy. In Mr Rudd’s view, Mr Xi would want to take Taiwan—ideally without a war—by the end of his fourth term in 2032. “The only thing that would prevent him would be effective and credible US, Taiwanese, and allied military deterrence—and Xi’s belief that there was a real risk of China losing any such engagement,” writes Mr Rudd.

Therein lies the rub. Who knows how Mr Xi would weigh up the risks? By surrounding himself with yes-men, he may have made it more difficult for dissenting views to percolate upwards. And Mr Xi is certainly a risk-taker. His purges of high-level officials, ostensibly for corruption, are a sign of that (millions must be quietly fuming at him). So are his displays of military muscle around Taiwan and shoals claimed by the Philippines. In both places a small clash could escalate. Even if Mr Xi’s behaviour so far has not been as reckless as Mr Putin’s, it may become more so.

Risk v endure

Yet Mr Xi’s writings (or those of his ghostwriters, overseen by Wang Huning, his chief ideologue and author of a gloomy book on the United States called “America against America”) are also laced with anxiety about threats to the party. He often urges officials to learn lessons from the Soviet Union’s collapse. In another book published this year, “The Political Thought of Xi Jinping”, Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London argue that Mr Xi’s ideology is mostly a cover. It is less about socialism and more about strengthening the party’s power. If the authors are right, it may suggest that Mr Xi’s focus is on preventing collapse. He would reckon that losing a war could trigger a regime-threatening backlash at home.

Indeed, it is far from clear that Mr Xi is really a Maoist or Marxist. Mao called for endless class struggle against bureaucratic elites and “capitalist roaders”. Mr Xi’s writings stress the need for stability. He has no truck even with protests by nationalists—there have been no large ones during his rule, unlike in preceding years.

In his handling of the economy, Mr Xi has scared entrepreneurs with his left-leaning talk. His “common prosperity” campaign, launched in 2021, raised the spectre of big new redistributive schemes. That effort coincided with a regulatory crackdown on large tech firms which smacked to some of an ideologically driven assault on the titans of private enterprise. But in the past year or two Mr Xi has been struggling to revive the economy. This has involved treating private firms with a softer touch and promoting high-tech manufacturing. It is hard to spot much in the way of socialism in his efforts. Some economists argue that more spending on welfare would help the economy by encouraging people to save less and spend more, but Mr Xi criticises doling out money for such purposes.

Two strands of Mr Xi’s thinking are far less in doubt to those who have studied him. One is his Leninism, meaning his emphasis on the party as an instrument of control. He blames the Soviet collapse on ideological laxity. He wants his officials to parrot well-worn doctrinal lines, rather than debate them.

The other strand is Mr Xi’s chest-thumping nationalism. The message conveyed by his works contrasts with that of Deng Xiaoping, who said China should “hide its capabilities and bide its time”. Mr Xi says China must move to the “centre of the global stage”. Some of Mr Trump’s picks for senior jobs believe this means more than a mere desire for great-power status (China has that already). “They are seeking to supplant us and they are seeking to replace democracy and capitalism with their one-party-form-of-rule techno-state,” said Mr Waltz last year.

Mr Xi is careful to avoid such language, but Mr Tsang and Ms Cheung agree that he wants global leadership. This is not “about taking over from the United States as the global hegemon, with all the baggage of US leadership”, they say. “It is also not about overtly overturning the liberal international order. The ultimate goal is to capture or ‘modernise and transform’ the international order into one that fits in with Xi’s thoughts.” That, clearly, would be a chilling world for democracy.

Yet for all the words Mr Xi has published, it is possible to misread them. “I sometimes worry that the sheer volume of Xi’s musings obfuscates more than it illuminates,” says Jonathan Czin, a former analyst of China at the CIA. “In China’s system, Xi is in effect both pope and emperor—responsible for ruling, as well as promulgating ideological justifications that read like an obscurantist theological treatise from the Middle Ages.”

As America and China struggle to make sense of each other during the new Trump era, misinterpretations will abound. That will make a fraught relationship all the more dangerous. ■

Middle East & Africa | America and the Middle East

Get ready for “Maximum Pressure 2.0” on Iran

The Trump White House may bomb and penalise the regime into a deal

Photograph: Imago

Nov 19th 2024|DUBAI

OCCASIONALLY, THERE are second acts in American diplomacy. During his first term, Donald Trump abandoned the nuclear pact agreed on in 2015 by Iran and world powers. He went on to pursue “maximum pressure”, crippling sanctions meant to compel Iran into a stricter agreement. It was only half successful: the sanctions battered Iran’s economy, but Mr Trump left office without a deal.

Now he may get another chance. Many of the sanctions have remained in effect under Joe Biden, but American enforcement has flagged: Iran’s oil exports climbed from less than 600,000 barrels per day (b/d) in 2019 to a high of 1.8m b/d earlier this year, almost all of them sold to China. People close to the president-elect are keen to resume the pressure in January—but such talk has prompted unease in the Middle East, and not only in Iran.

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

Though Mr Trump has been vague about his plans, many of his cabinet nominees support tougher sanctions. Marco Rubio, his pick for secretary of state, opposed the original nuclear deal and criticised Mr Biden for his failure to enforce an oil embargo. Mike Waltz, Mr Trump’s choice as national security adviser, wants to “reinstate a diplomatic and economic pressure campaign” against Iran.

There may be dissenting voices, such as Tulsi Gabbard, who is tipped to be director of national intelligence. But advocates of fierce embargoes have spent four years making detailed plans for how to implement them and the sceptics have no clear alternative. The new administration will probably go with the ready-made policy.

Tougher American enforcement could well block up to 1m b/d of Iranian exports. That could halve Iran’s oil revenue at a time when its budget deficits are already widening fast. What is more, Mr Trump might be able to avoid a big rise in American petrol prices. The International Energy Agency, a global forecaster, predicts an oil-supply glut of more than 1m b/d in 2025. The market could probably absorb the loss of some Iranian crude.

Still, the effect might be temporary, since Iran has built a resilient network to defy sanctions. So the question is what America wants to achieve; sanctions are meant to be a means, not an end. For some hardliners in Washington, the ultimate goal has always been regime change.

That may be a minority view, but there is broad consensus beyond the incoming administration that a new nuclear deal is necessary. Even some supporters of the original agreement, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), think there is no going back to it. The JCPOA sought to keep Iran’s “breakout time”, the period it would need to produce a bomb’s-worth of enriched uranium, to around one year. It limited Iran’s uranium stockpile to 300kg enriched to 3.67% purity.

Iran has blown past those limits. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the UN’s nuclear watchdog, estimated in October that Iran had more than 6,600kg of uranium enriched to various levels. That included 182kg at 60% purity, a hair’s breadth from weapons-grade. It has also resumed production of uranium metal, which can be used to make the core of a nuclear bomb. Iran could probably produce a bomb’s-worth of enriched uranium in less than two weeks. Reviving the jcpoa would lengthen that time-frame—but it would still be far less than a year.

Ask and ye might receive

America could ask for many things in a new deal. It could insist that Iran dismantles some of its nuclear facilities, particularly those that were used in the past for weapons research. It could require Iran to implement the Additional Protocol, an addendum to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty which gives the IAEA further inspection powers. Beyond capping enrichment, a new deal could also try to restrict Iran’s missile programme, or demand that Iran curtails its military support for its proxies.

The problem is that diplomats have tried to negotiate some of these provisions in the past. Iran refused. This is where advocates of maximum pressure think Mr Trump is their secret weapon: he could threaten to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities if diplomacy fails, and he might seem crazy enough that Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, would take him seriously.

Mr Khamenei may not, though. After a year of back-and-forth missile attacks between Iran and Israel, many conservatives in Iran would be reluctant to negotiate away their nuclear programme. Instead he could try to call Mr Trump’s bluff. He knows that the new president does not want a war with Iran and that some of his allies are keen to disengage from the Middle East in order to focus on China. Rather than a comprehensive accord, Iran could propose a limited one that simply pulls its nuclear programme back from the threshold. It could offer to get rid of its stockpile of 60%-refined uranium, by blending it down or by shipping it out of the country, and to cap enrichment once again.

This would be hard for Mr Trump to defend, a far weaker agreement than the one he abrogated in 2018. But he could argue that his predecessor left him a mess. A more limited deal would find some support in Iran, too. Hardliners seem to have accepted that they cannot muddle along without sanctions relief.

Binyamin Netanyahu opposed the JCPOA and has dreamed for years that America might attack Iran’s nuclear facilities. But he would struggle to sabotage the new administration’s diplomacy. The Israeli prime minister has long promoted Mr Trump as Israel’s greatest champion in America; it would be ironic if Mr Trump ended up securing Republican support for a watered-down agreement with Iran.

Gulf states, meanwhile, worry that he will fail. Faisal bin Farhan, the Saudi foreign minister, supported maximum pressure during Mr Trump’s first term; now he talks cheerily about how Saudi Arabia’s relations with Iran are “on the right path”. The Saudis are keen to avoid a repeat of Mr Trump’s first term, when Iran targeted their oilfields. Prince Faisal visited Iran last summer, the first such trip in seven years. There is talk of joint military exercises.

The kingdom has also tried to distance itself from Israel. At a conference in Riyadh earlier this month, Muhammad bin Salman, the crown prince, condemned Israel not only for its wars in Gaza and Lebanon but also for its recent air strikes on Iran. The Saudis worry that Mr Trump may want them to cut ties with Iran and have urged the coming administration not to shatter their fragile detente. With the Middle East mired in an ever-widening war, few are in the mood to take risks. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

A rise in antisemitism puts Europe’s liberal values to the test

The return of Europe’s oldest scourge

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Nov 21st 2024

In 1945, as Europe smouldered and the moral reckoning of the Holocaust lay ahead, Karl Popper pondered the paradox of tolerance. An open society needs tolerance to thrive, the Austrian-born philosopher posited. But extending that intellectual courtesy to the prejudiced would result in the undermining of the very tolerance that made their intolerance possible in the first place. Popper concluded it was on balance better to nip the bigots in the bud early on and save everyone the kind of trouble his home continent (and Popper personally, given his Jewish heritage) had just been through. The history of post-war Europe, at first in the west and then in the former communist bloc, is one of polities striving to balance the right of allowing everyone to say what they please while preserving the liberal society Popper sought to bring to life.

A form of intolerance that should have seen its last in 1945 has made a discomfiting return. Antisemitism, never quite expunged from the continent but once banished beyond the political pale, is so rife in Europe now that 96% of Jews say they have experienced it in the past year. More than half say they fear for their safety; the same number have either emigrated or considered doing so in recent years. Physical attacks, while rare, are rife enough that three-quarters of Jews occasionally avoid wearing religious symbols in public. Even more worrying these statistics, compiled by the European Union for a report released in July, were based on data gathered before the terrorist attacks by Hamas in October 2023, and the brutal Israeli response. Every indicator has become worse since then. A dispiriting flow of antisemitic incidents reached an apogee in the wake of a football match involving a team from Tel Aviv playing in Amsterdam on November 7th, after which Israeli visitors—some of them behaving even more boorishly than is customary for football fans, including tearing down Palestinian flags and worse—were chased in the streets by mobs in what the city’s mayor described as a “pogrom”. Rabbi Menachem Margolin, chairman of the European Jewish Association, warned of Europe “going down the darkest path again”.

The continent suffers from three sorts of antisemitism. The first is the kind of bigotry, soft or hard, that people in Popper’s era might have recognised. It is the prejudice that puts the greedy Jew (preferably with a hooked nose) at the centre of all manner of conspiracy theories, from hoarding gold to controlling the media/banks/politics. An offshoot of ancestral intolerance, it became the preserve of the extreme right: think of Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the French party now known as the National Rally, describing the Nazi gas chambers as “a detail” of history. The resurgence of this type of prejudice has been fuelled by the advent of the internet, whose dark corners are the spiritual home of crackpots.

The second antisemitism is one that can be thought of as an unwelcome import through waves of migration. New arrivals to Europe in the past six decades or so often came from Muslim-majority countries. Some lacked the liberal cultural mores which most Europeans (debatably) believe themselves to exemplify, and justifiably felt no guilt for the Holocaust nor what preceded it. A sympathy for the Palestinian cause hardened attitudes to Jews in ways that sometimes resembled Mr Le Pen’s tirades. Even as the migrants became the parents of European-born children, the bigotry all too often endured. In France, the EU country with both most Jews and Muslims, 55% of the latter think the former are too powerful in politics (a claim that can easily be dismissed as fanciful). Across Europe, perceptions of prejudice against Jews have risen most in places that have taken in lots of migrants in recent years, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Add to this a third antisemitism linked to some Europeans’ anger at the Israeli government of the day, which shoots up in the wake of strife in the Middle East (ie, all too regularly). Protesting against the actions of Israel in Gaza is legitimate, everyone agrees, but also acts as a pretext for those who hold less acceptable views about Jews. Drawing the line between what is fair criticism and what is covert bigotry can be hard: Germany recently passed a resolution combating antisemitism that critics—including Jewish ones—say stymies legitimate discussion of any Israeli misdeeds.

Whose antisemitism is it anyway?