The Economist Articles for Dec. 4th week : Dec. 22th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간24.12.14조회수262 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Dec. 4th week : Dec. 22th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

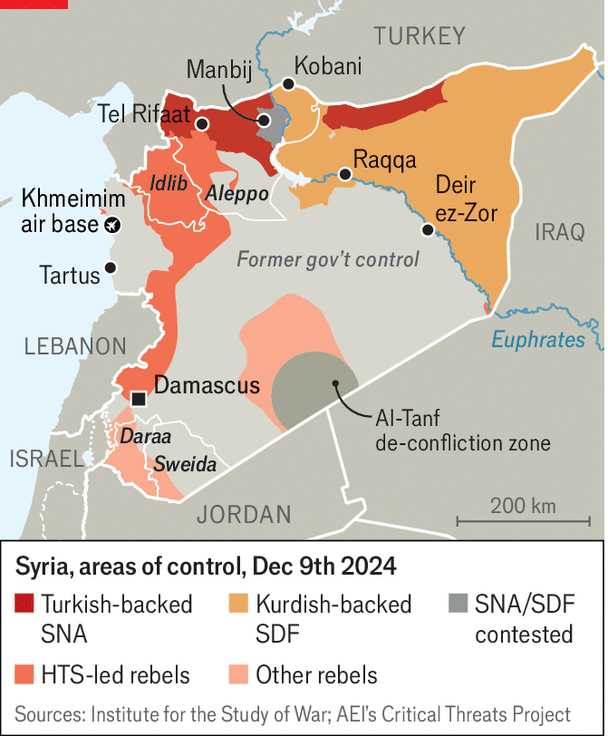

Leaders | The end of the house of Assad

How the new Syria might succeed or fail

Much will go wrong. But for now, celebrate a tyrant’s fall

Dec 12th 2024

AFTER 53 YEARS in power, the house of Assad left behind nothing but ruin, corruption and misery. As rebels advanced into Damascus on December 8th, the regime’s army melted into the air—it had run out of reasons to fight for Bashar al-Assad. Later, Syrians impoverished by his rule gawped at his abandoned palaces. Broken people emerged blinking from his prisons; some could no longer remember their own names.

Now that Mr Assad has fled to Moscow, the question is where will liberation lead. In a part of the world plagued by ethnic violence and religious strife, many fear the worst. The Arab spring in 2010-12 taught that countries which topple their dictators often end up being fought over or dominated by men who are no less despotic. That is all the more reason to wish and work for something better in Syria.

There is no denying that many forces are conspiring to drag the country into further bloodshed. Syria is a mosaic of peoples and faiths carved out of the Ottoman empire. They have never lived side by side in a stable democracy. The Assads belong to the Alawite minority, which makes up about 10-15% of the population. For decades, they imposed a broadly secular settlement on Syrian society using violence.

Syria’s people have many reasons to seek vengeance. After 13 years of civil war in a country crammed with weapons, some factions will want to settle scores; so will some bad and dangerous men just released from prison. Under the Assads’ henchmen, many of them Alawite and Shia, Sunnis suffered acts of heinous cruelty, including being gassed by chlorine and a nerve agent.

Syria’s new powerbrokers are hardly men of peace. Take the dominant faction in the recent advance. Until 2016 Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was known as Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda. Its founder, Ahmad al-Sharaa, had fought the Americans as a member of Islamic State (IS) in Iraq under the nom de guerre Abu Muhammad al-Jolani. HTS and Mr Sharaa swear they have left those days behind. If, amid the chaos, such groups set out to impose rigid Islamic rule, foreign countries, possibly including the United Arab Emirates, will bankroll other groups to take up arms against them.

Indeed, some of those foreign countries are already fighting in Syria to advance their own interests. In the north, Turkey’s proxies are clashing with Kurds who want autonomous rule. In central Syria, America is bombing IS camps, for fear the group will rekindle its jihad. Israel has destroyed military equipment and chemical weapons—and encroached deeper into the Golan Heights, occupying more Syrian territory.

With so much strife, no wonder many share a fatalistic belief that Syria is doomed to collapse into civil war once again. If it does so, they rightly warn, it will export refugees, jihadists and instability beyond the Middle East and into Europe.

But despair is not a policy. At the least, the Assads’ fall is a repudiation of Iran and Russia, two stokers of global chaos. And witness the jubilation in Syria this week: a nation exhausted by war could yet choose the long road towards peace.

The essential condition for Syria to be stable is that it needs a tolerant and inclusive government. The hard-learned lesson from the years of war is that no single group can dominate without resorting to repression. Even most of the Sunni majority do not want to be ruled by fundamentalists.

The daunting task of attempting to forge a new political settlement out of a fractured country could well fall to Mr Sharaa. As ruler of Idlib, a rebel province in the north, he ran a competent government that nodded at religious pluralism and oversaw a successful economy. However, although he has distanced himself from more radical groups and courted the West, Mr Sharaa has become increasingly autocratic, and had taken to purging rivals and imprisoning opponents.

His interim national government, announced this week, is exclusively made up of HTS loyalists. Because it is laying claim to a dysfunctional state, competence and order will go a long way. Yet if Mr Sharaa attempts to run Syria permanently as a giant Idlib—a Sunni fief dominated by HTS—he will fail. Syria will remain divided between feuding warlords, many of them mini-dictators in their own right.

Syria will also fail if it becomes an arena for the rivalries of outside powers. It is more likely to prosper if it is left alone. And only if it prospers will millions of refugees choose to return home. That is especially important for Turkey, which is weary of the 3m Syrians living there. As a backer of HTS, it will be hoping for contracts in a thriving country. Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, should also understand that the best way to weaken calls for Kurdish self-rule is to create a Syria where the Kurds and other minorities have a voice.

The world may not like HTS, but to sabotage the creation of a stable government would risk the poison spreading to Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon. America and Saudi Arabia should therefore prevail upon Israel, Turkey and the UAE not to ruin Syria’s chances. If Mr Sharaa emerges as a plausible national leader, the West should be prepared to speedily remove its designation of HTS as a terrorist group.

The new Syria has one great gift: it can be rid of Iran and Russia. They spent tens of billions of dollars to keep Mr Assad in power, but the tyrants in Tehran and Moscow proved no more able to sustain despotism in a country that had rejected its despot than the West was able to sustain democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan. Russia has failed to realise its imperial ambitions—a message that will echo in the Caucasus and Central Asia. In little over a year, Iran has seen its proxies defeated in Gaza, Lebanon and now Syria. Its benighted influence in the Middle East has shrunk dramatically, possibly opening space for negotiations with the incoming Trump administration.

Much will go wrong in a traumatised place like Syria. The effort to rebuild the country is bound to entail a struggle for influence. Its strongmen will need reserves of courage, foresight and wisdom that they have yet to reveal. But before writing off the future, pause for a moment and share Syrians’ joy at bringing down a tyrannical dynasty. ■

Leaders | Artificial exuberance

America’s searing market rally brings new risks

Financial innovation is just as much to blame as the technological sort

Illustration: Rose Wong

Dec 11th 2024

SINCE AMERICA elected Donald Trump as president on November 5th, the value of its listed firms has increased by $4.2trn, more than the entire worth of London’s stockmarket. The S&P 500 is up by nearly 30% this year. At 23 times its forward earnings, the index has rarely been so highly rated by investors. Nor, in recent years, have its constituents been able to borrow more cheaply. The cost for risky companies of raising funds is at its lowest relative to Treasury bonds since the spring of 2007. Everywhere you look, there are signs of exuberance. This month the price of bitcoin reached $100,000. And all this is happening despite positive real interest rates.

What is going on? A familiar part of the explanation is that American technological innovation has made investors giddy. No two businessmen exemplify the boom better than Jensen Huang, whose firm sells artificial-intelligence (ai) chips, and Elon Musk, who makes electric vehicles and rockets, and will be part of Mr Trump’s administration. Their two firms, Nvidia and Tesla, are part of the “Magnificent Seven” which now account for a third of the S&P 500’s market value and a quarter of its profits—an extraordinary degree of concentration.

Chart: The Economist

Less remarked upon, however, is the wave of financial innovation that is under way, and which brings new risks. The Schumpeterian urge burns as hot among the country’s financial engineers as it does for those who build real things. Exchange-traded funds (ETFs), for instance, have accelerated their decades-long rise. Those listed in America now manage $11trn-worth of assets, and come in increasingly speculative forms. Investors can now buy ETFs that provide leveraged exposure to Nvidia and Tesla—or even MicroStrategy, a software firm raising billions to purchase bitcoin, whose share price has shot up by around 500% this year.

The structural changes taking place in private markets are no less dramatic. On average, share prices in the three biggest private-markets firms have risen by more than those of the Magnificent Seven this year. Private-credit providers are nosing into lending markets once dominated by banks, often funding investments with life-insurance policies. A Cambrian explosion of products for individual investors is under way.

Their architects are not bankers. Quant firms such as Jane Street are minting fortunes making markets in ETFs. The popularity of such low-cost investment products has squeezed active portfolio managers; survivors have migrated to huge multi-manager hedge funds such as Citadel and Millennium. BlackRock, dominant in public markets, is targeting private ones: this month it agreed to buy HPS, a lender. Apollo, a private-markets firm with a big insurance arm, is moving the other way. It plans to launch a private-credit ETF.

Investors buying the most speculative new products are likely to end up disappointed. Firms consolidating the private-credit industry today risk doing so at the top of the market.

What matters more is the risk this rapid innovation poses to the broader financial system. Regulators face at least a dozen growing non-bank institutions which on the basis of their size, novelty, opacity and interconnectedness may be deemed systemically important. Some of these companies may indeed efficiently shift risk away from the banking system, which is always vulnerable to runs by depositors. But deciding which of them strengthen the system in this way, and which pose new, unacceptable and poorly understood threats, is the most urgent question in financial regulation today.

That may not be a priority for Mr Trump, whose interest in regulation appears to centre on lifting rules for the crypto industry (see Buttonwood). Yet today’s sky-high asset prices lend the task urgency. Markets show signs of becoming more fragile. In August the VIX, a measure of stockmarket volatility, recorded its biggest-ever one-day spike as hedge funds unwound highly leveraged currency trades. Equity investors react more and faster to company earnings than they used to. In debt markets, reports from business-development companies, a type of investment vehicle, indicate plenty of sloppy lending in private credit.

Some investors acknowledge that returns in years to come may be lower. But many are too sanguine about the risk of a market crash. Although volatility has returned to normal and default expectations are benign, minds could change quickly. Imagine that one of America’s tech champions suddenly issues a gloomy outlook and that financial innovators also turn out to have misunderstood the risk contained in their new products. Markets would be falling from a very great height. ■

By Invitation | Holding the line

South Korea’s crisis highlights both fragility and resilience, writes Wi Sung-lac

The country is deeply polarised, but its living memory of military rule strengthens its commitment to democracy

Illustration: Dan Williams

Dec 11th 2024

The audio version of this story is available in our app. It has been produced using an AI voice. Learn more.

President Yoon Suk Yeol’s declaration of martial law on December 3rd brought a profound sense of déjà vu to many South Koreans, evoking memories of the military coups from the 1970s and 1980s. For decades, South Koreans had believed that such events were consigned to the past. Yet the martial law declared by President Yoon shocked not only Koreans but the entire world. It exposed both the fragility and the resilience of democracy in South Korea. Although the immediate threat was averted, the situation remains fraught with uncertainty.

The crisis reveals two critical weaknesses in South Korea’s democracy. The first is the highly polarised political environment that allowed Mr Yoon—an anti-democratic, anti-political, dogmatic figure with no political experience—to rise to the presidency. He never shed the mental habits of a prosecutor when he entered politics. Mr Yoon lacks the capacity for political dialogue or compromise. His binary mindset, where people were either guilty or innocent, led him to view political opponents as enemies to be eliminated. With far-right leanings, self-righteousness and impulsiveness, Mr Yoon exhibits traits reminiscent of dictators from history.

Mr Yoon gained prominence by prosecuting former President Park Geun-hye and clashing with President Moon Jae-in, earning a reputation for independence. South Korea’s political polarisation allowed the conservatives to overlook his authoritarian tendencies, adopting him as a presidential candidate to prevent another progressive administration. As president, Mr Yoon has wielded power to target political opponents, shielding himself and his wife from mounting legal difficulties. His administration became notorious for its abuse of prosecutorial power, becoming, in a perversion of Lincoln’s famous phrase, a government of the prosecution, by the prosecution, and for the prosecution.

The second fragility is the lingering interference exerted by South Korea’s military and intelligence agencies on politics (and political manipulation in those agencies in turn). Despite efforts to depoliticise these institutions, certain people with political ambitions remain entrenched, misusing their personal networks based on military-school ties. Mr Yoon manipulated these networks, appointing his high-school peers to top positions in the military and intelligence services.

The president exploited these two South Korean fragilities to consolidate his power. As his administration faced mounting scandals after a decisive defeat in the April parliamentary election, he resorted to extreme measures instead of seeking compromise. With his political survival at stake, Mr Yoon and his loyalists in military and intelligence agencies declared martial law, sought to shut down the press, and tried to use military force to dismantle the parliamentary majority of opposition parties.

The coup attempt failed when opposition lawmakers swiftly convened in the National Assembly to lift martial law. Of the 300 lawmakers, 190 gathered, including 18 from Mr Yoon’s own party, and unanimously passed the resolution. This moment underscored South Korea’s democratic resilience.

Traditionally, coup leaders in South Korea have suppressed such resolutions by arresting lawmakers or dissolving the legislature. This time, citizens, opposition parties and the media played pivotal roles in resisting. The leader of the opposition Democratic Party, Lee Jae-myung, livestreamed in his car on the way to the National Assembly, calling for citizens to protect the institution. Citizens gathered in the cold, surrounding the National Assembly building to protest, and the citizen action became the first line of defence for democracy.

Democratic Party lawmakers, embedded with the spirit of defending democracy that stretches back through South Korea’s pro-democracy movements, climbed over fences to bypass police blockades and enter the National Assembly. Special forces advanced to within metres of the main assembly hall where I was gathered with other legislators to vote on lifting martial law. Amid tense confrontation, staffers resolute in their commitment, built barricades to block them from entering. On-site media coverage also played a crucial role, limiting the military actions. These acts of defiance bought precious time for the vote.

The coup’s failure was also due to the rushed and poorly executed operation by a few leaders of the military and police. Rank-and-file soldiers and mid-level commanders were reluctant to attack civilians or lawmakers, a hesitation probably influenced by historical reckoning with past military atrocities like the Gwangju Massacre, a slaughter of hundreds of pro-democracy protesters against martial law in 1980. These factors culminated in the successful resistance in the latest crisis.

However, the battle is not over. The aftermath of the failed coup remains uncertain. Impeachment proceedings against President Yoon, despite overwhelming public support, were blocked by him and his conservative allies, allowing him to remain in office and plot a counteroffensive. Public sentiment is boiling. It is not clear whether South Korea’s fragility or resilience will prevail.

Strengthening the resilience must begin with the resignation or the impeachment of the president who orchestrated the coup, along with holding the individuals involved accountable. This would mark an additional historical reckoning, reaffirming democratic principles and ensuring such abuses are never repeated. In parody of Lincoln’s famous line, a government of the prosecution, by the prosecution, and for the prosecution must perish from the earth. Furthermore, to prevent the rise of authoritarian figures, we must address political and social polarisation, depoliticise the military and intelligence agencies, and strengthen the resilience of democracy by fostering sustained political dialogue. There must be greater military transparency and guaranteed civilian oversight, and promotion of public awareness of democratic values and rights.

As political polarisation deepens globally, South Korea’s experience serves as a reminder that no democracy is immune to such threats. Martial law in Korea highlighted that democracy relies not just on institutions but on active citizen engagement, constant vigilance and the collective resolve of citizens and leaders. South Korea’s struggle offers invaluable lessons for all.■

United States | Tort report

America’s best-known practitioner of youth gender medicine is being sued

Johanna Olson-Kennedy leads the Centre for Transyouth at LA’s Children’s Hospital. One of her patients thinks she has been negligent

Photograph: Melissa Lyttle/Redux/eyevine

Dec 6th 2024|NEW YORK

JOHANNA OLSON-KENNEDY is among the most celebrated youth gender-medicine clinicians in the world. She has been the Medical Director of the Center for Transyouth Health and Development at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), one of the first high-profile American youth gender clinics and presently the largest, since 2012. A frequent expert witness in court cases who is often quoted in the media, Dr Olson-Kennedy also leads a $10m initiative funded by the National Institutes of Health to study youth gender medicine—by far the largest such project in America. In addition, she is the president-elect of the United States Professional Association for Transgender Health.

As state-level bans on youth gender medicine have accumulated, and are being tested at the Supreme Court, this controversial field has been seized by a fierce debate over the proper role of mental-health assessments. The Dutch clinicians who published the seminal youth gender-medicine protocol in 2012 emphasised the importance of conducting a careful, in-depth assessment prior to starting a young person on puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones. But Dr Olson-Kennedy has emerged as a critic of what she views as undue and unnecessary “gatekeeping”. “I don’t send someone to a therapist when I’m going to start them on insulin,” she told the Atlantic in 2018. In her published research, Dr Olson-Kennedy has reported prescribing cross-sex hormones to patients as young as 12, and referring patients as young as 13 for double mastectomies.

Now, however, Dr Olson-Kennedy is being sued by a former patient, Clementine Breen, who believes that she was harmed precisely by a lack of gatekeeping. And many of Ms Breen’s claims appear to be backed up by Dr Olson-Kennedy’s own patient notes, which Ms Breen and her legal team have shared with The Economist. The medical-negligence lawsuit was filed on December 5th in California.

Ms Breen is a 20-year-old drama student at UCLA whose treatment at Dr Olson-Kennedy’s clinic included puberty blockers at age 12, hormones at 13 and a double mastectomy at 14. She stopped taking testosterone for good about a year ago and then began detransitioning in March. The lawsuit’s defendants are Dr Olson-Kennedy, the gender therapist to whom Dr Olson-Kennedy referred Ms Breen, the surgeon who performed the double mastectomy and 20 as-yet-unnamed “Doe Individuals” who were “agents, servants, and employees of their co-defendants.” Ms Breen’s lawyers accuse them of medical negligence on a number of grounds, including lack of psychological assessment, poor management of her mental health and a lack of concern about the effects of puberty blockers on her bone health.

Why sue? Ms Breen is seeking monetary damages. But she also cites “personal closure reasons” in an interview, as well as a desire to rebut the notion that rushed youth gender transitions are rare in America, a claim commonly made by some activists. “People are just brushing exactly what happened to me off as something that doesn’t happen,” she says.

While little is known about the practices of American youth gender clinics, Dutch-style assessment does not appear to be the norm. None of the 18 American youth gender clinics contacted by Reuters for an investigation published in 2022 described such a protocol. The share of Americans who regret their gender transitions, or who detransition, is unknown too. Anecdotally there appears to be an uptick in the number of detransitioners seeking redress, says Jordan Campbell, one of Ms Breen’s lawyers. His firm, which focuses on detransitioners, has been approached by more than 100 people but has pursued litigation on behalf of less than a fifth.

In most instances state statutes of limitations make it all-but-futile for detransitioners to pursue legal claims, or the potential client ultimately decides against the often-bruising experience of doing so. In Ms Breen’s case, though, her treatment was recent enough to allow her to sue her providers and she is willing to speak out. That—and Dr Olson-Kennedy’s perch at the very top of her field—is what makes Ms Breen’s case particularly noteworthy. And if plaintiffs like Ms Breen prevail, health-care systems in states where these treatments are still legal—always wary of lawsuits and the potential of rising premiums for medical-malpractice insurance—might take a more conservative approach to youth gender medicine, or even abandon offering it altogether.

Ms Breen’s story starts early in the 2016-17 school year, when she turned 12. She felt depressed and sought help from a counsellor. “I mentioned that I might be trans,” she recalled in the interview, “but I also mentioned that I might be a lesbian and that I might be bisexual, like I wasn’t really sure about my identity at all.” In retrospect, she said, she believes that her unsettled feelings about going through puberty stemmed from a violent situation at home involving her older brother, who has severe autism, as well as abuse she experienced at the hands of someone outside the family when she was six years old, which she did not disclose to anyone until much later.

Ms Breen and her lawyers claim that despite the vagueness of her musings about her identity, her counsellor fixed on the possibility that she was transgender. “Based on those conversations and few statements, the counsellor called Clementine’s parents and told them she believed Clementine was transgender,” they write in the complaint. With the support of her school, Ms Breen, who went by the name Kaya at the time, changed her name to Kai and her pronouns to he/him. Her parents took her to the CHLA gender clinic, and Ms Breen’s first appointment there, records show, was in December 2016.

Dr Olson-Kennedy’s notes from that first visit show that she immediately set Ms Breen down a path towards medical transition. She writes that Ms Breen had not yet seen a gender therapist and had come out as trans three months earlier. Nevertheless, she asserts that Ms Breen meets the specific Diagnostic and Statistical Manual criteria for gender dysphoria, one of which, she writes, is a cross-sex identity that has lasted for six months or longer.

At the time of this appointment, the latest guidelines for gender-medicine practitioners, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s (WPATH) Standards of Care Version 7, noted that “Before any physical interventions are considered for adolescents, extensive exploration of psychological, family, and social issues should be undertaken, as outlined above. The duration of this exploration may vary considerably depending on the complexity of the situation.”

Three months later, Ms Breen returned to CHLA to have a puberty-blocker implant inserted into her left arm. “I still have the scar—it’s very little, but it’s right here,” says Ms Breen, showing it on a Zoom call. From there, her path towards fully irreversible treatments was swift. Medical records show that less than a year later Dr Olson-Kennedy prescribed testosterone for Ms Breen. In May 2019 Ms Breen, who was 14 at the time, had a double mastectomy.

Ms Breen and her lawyers claim in their lawsuit that when her parents expressed reservations about testosterone, Dr Olson-Kennedy spoke with them away from Clementine. “Dr Olson-Kennedy first told them that Clementine was suicidal,” they write in the complaint. “At that time, Clementine had never had any thoughts of suicide, and she certainly had never expressed anything along those lines to Dr Olson-Kennedy. Dr Olson-Kennedy went even further [...] by telling them that if they did not agree to cross-sex hormone therapy, Clementine would commit suicide.”

Because Ms Breen’s parents declined an interview request, Ms Breen herself is the only source for this claim. It is true, however, that there is no mention of suicide risk in any of Dr Olson-Kennedy’s notes before Ms Breen’s double mastectomy, and the visit notes for the appointment when Dr Olson-Kennedy ordered testosterone describe Clementine’s (then Kai’s) mental state as “Alert… No acute distress… Cooperative, Smiling.” Even if Ms Breen had been suicidal, the evidence that cross-sex hormones ameliorate suicidality is thin: in a 2021 systematic review on the effects of cross-sex hormones on trans people commissioned by the World Professional Association of Transgender Health, the authors write that due to a lack of quality published research, “We could not draw any conclusions about death by suicide.”

Fluid recordkeeping

Perhaps the lawsuit’s most damning claim is that Dr Olson-Kennedy misrepresented Ms Breen’s gender-identity history in the letter of support she wrote to Ms Breen’s surgeon. In the letter, quoted in the complaint and also obtained in full by The Economist, Dr Olson-Kennedy writes that Ms Breen had “endorsed a male gender identity since childhood”—language intended to signal that a young person’s gender identity has been stable for a long time, alleviating concerns that the patient might change their mind. But the claim was contradicted by Dr Olson-Kennedy’s own records. (Dr Olson-Kennedy did not respond to a request for comment through her hospital. Ms Breen’s surgeon declined to comment through his lawyer.)

Save for a fleeting period of improved mood following the insertion of the implant, Ms Breen says that she does not believe any of these treatments made her feel better. In fact, her mental health began to decline after she went on testosterone.

The CHLA team prescribed and tweaked various psychotropic medications, but nothing in the records suggests anyone at the hospital questioned whether the transition was helping rather than harming Ms Breen, despite what appear in retrospect to be some warning signs. By July 2020 she was having a “very difficult time remembering” her weekly testosterone shots, and was missing three quarters of them, Dr Olson-Kennedy wrote at the time (Dr Olson-Kennedy switched her to a gel). Three sentences after mentioning this, Dr Olson-Kennedy expresses the opinion that “Kai” “would probably benefit from an increased dose of testosterone.” A psychiatrist at CHLA wrote after a September 2020 telehealth visit that Clementine was at that time engaging in “compulsive cutting to see if he has blood.” Later in the notes he explained that Clementine “has a complex diagnosis that includes tics, psychosis, obsessions, and compulsions”.

Ms Breen says she is doing significantly better today—partly, she believes, simply because she ceased taking testosterone. But well before that, she ditched the therapist Dr Olson-Kennedy referred her to, who she said fixated entirely on her gender identity. She switched to a dialectical behavioural therapist whom she described as a godsend, with whom she had her first-ever in-depth conversations about the physical and sexual abuse she endured earlier in life. Ms Breen says she is fairly confident that if she’d had these conversations at age 12, she wouldn’t have pursued medical transition. She has been left with a lower voice than she wants, an Adam’s Apple that distresses her, the prospect of breast reconstruction if she wants to partially regain a female shape, and the possibility that she is infertile due to the years she spent on testosterone.

In a statement provided to The Economist, CHLA notes “we do not comment on pending litigation; and out of respect for patient privacy and in compliance with state and federal laws, we do not comment on specific patients and/or their treatment.” Unfortunately, the paper trail that shines a light on Dr Olson-Kennedy’s approach to Ms Breen’s care does not exist for her former therapist, whom we also contacted for comment. California state law requires therapists to retain patient visit notes for five years. But the therapist Ms Breen is suing told us, via a lawyer, that almost all of the notes were unavailable, due to water damage. ■

United States | Message in a bullet

Luigi Mangione’s manifesto reveals his hatred of insurance companies

The man accused of killing Brian Thompson gets American health care wrong

Photograph: AP

Dec 12th 2024|CHICAGO

Homicide investigations are like bankruptcies: they come along gradually and then all at once. On December 9th, Luigi Mangione, a 26-year-old engineering graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League school, was arrested and charged with murdering Brian Thompson, the ceo of UnitedHealthcare, America’s biggest health insurer, in a predawn assassination in Manhattan on December 4th. The arrest came after five days of frenetic investigation in which police seemed to have almost no leads at all. The fugitive was finally captured in a branch of McDonalds in Altoona, a town in central Pennsylvania, after a member of staff recognised his face from a security camera photo circulated by the police.

Mr Mangione, of course, is legally innocent until proven guilty. But the public evidence against him is piling up. Police say the arresting officers discovered a fake New Jersey id of the sort the killer apparently used to check into a hostel in Manhattan, as well as a 3D-printed gun, a silencer, and a bundle of cash. (Mr Mangione apparently disputes this last detail). There was also a 262-word handwritten note that included the passage: “I do apologise for any strife or traumas but it had to be done. Frankly, these parasites simply had it coming.” Health insurers, he wrote, are “too powerful, and they continue to abuse our country for immense profit.”

Despite his writings, Mr Mangione did not seem determined to get caught. He skillfully eluded his pursuers. He apparently arrived in New York and left again by bus; covered his face for much of his time in the city, may have used a “burner” phone; and paid for things exclusively in cash. Searches in Central Park had turned up a backpack that the killer had apparently discarded, but it contained only a jacket and a bundle of Monopoly money. Had he not revealed his face to a security camera for a few seconds in the hostel, or been recognised by an eagle-eyed burger flipper, he might very well still be free.

Mr Mangione now faces five criminal charges in New York City, including second-degree murder. He is also charged with weapons offences and using a false id in Pennsylvania. He is currently fighting extradition back to the Empire State, a process that could take several weeks to resolve. He will then have to plead formally to the charges. His lawyer suggested he intends to plead not guilty.

What could have inspired the killing? Mr Mangione’s short note suggested a calculating desire to wreak revenge on America’s health-care system. America, he correctly noted, has the most expensive health care in the world, but life expectancy has stagnated. “Many have illuminated the corruption and greed” in the system, he wrote. “Evidently I am the first to face it with such brutal honesty.”

Chart: The Economist

Biographical details add some context. Mr Mangione belongs to a wealthy Italian-American family from Baltimore. He was the valedictorian of his elite private school in the city. After studying computer science and graduating from Penn in 2020, he lived in Hawaii, working as a data engineer for TrueCar, a car-buying website. Though clearly fit and active, according to friends in Hawaii, he suffered chronic back pain, possibly made worse by a surfing injury. In 2023 he apparently underwent back surgery. On his Reddit account, he posted an X-ray image of a spine with several bolts implanted into it. About six months ago he disappeared, cutting contact with friends and family, until reappearing in Altoona.

If his goal was to get America discussing its health-care system, Mr Mangione seems sure to succeed. In the days leading up to his arrest, three words written on the casings of the bullets used to kill Mr Thompson—“deny”, “defend” and “depose”—seemingly intended to echo words used by insurance companies while rejecting claims, became a meme. On TikTok sympathisers made out the then mysterious killer was some sort of superhero, with influencers singing ballads to him and getting tattoos of his face.

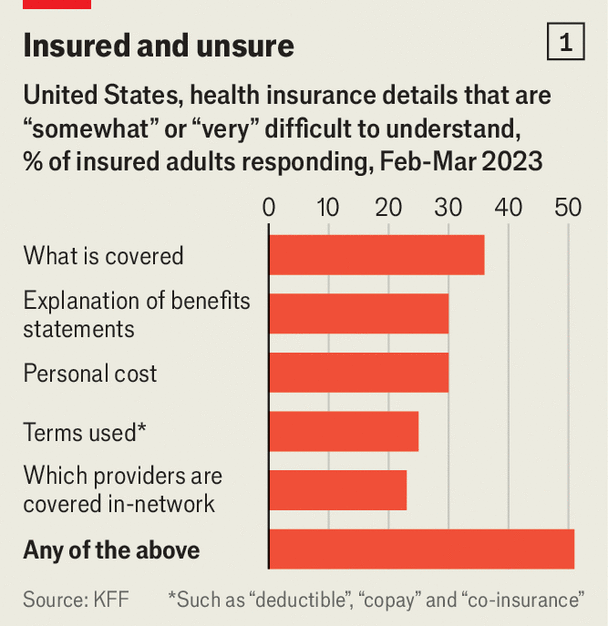

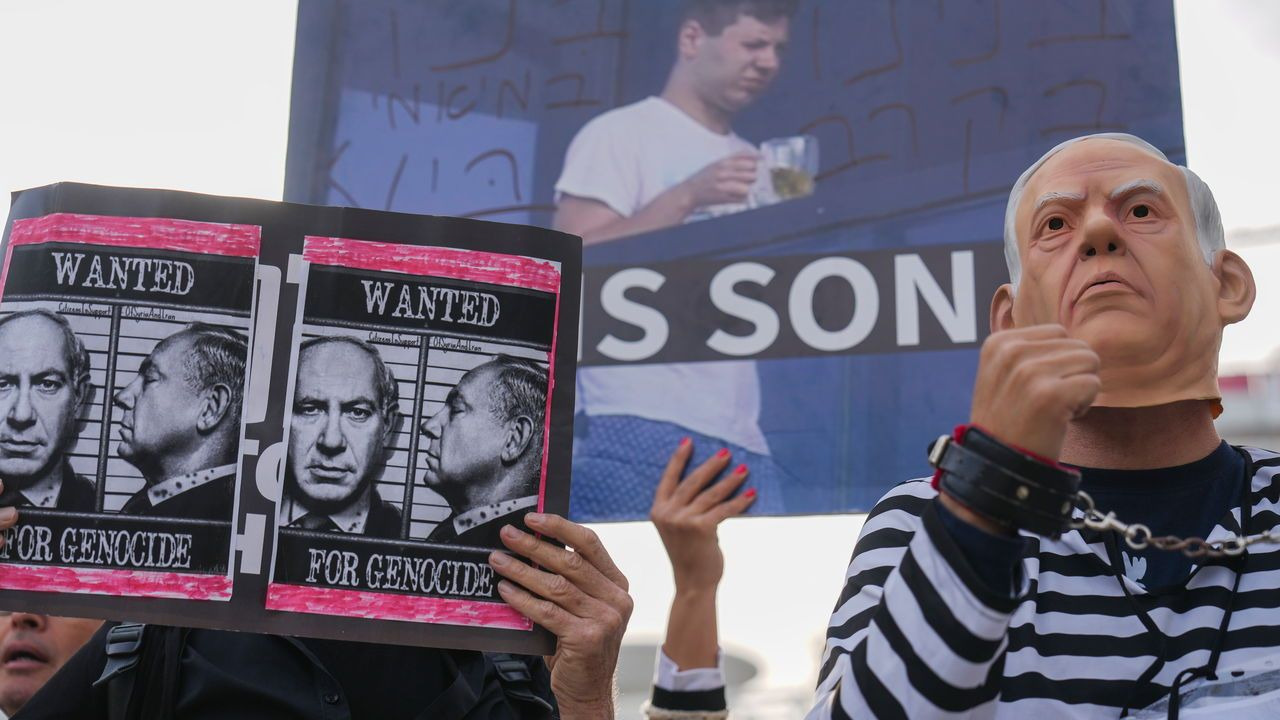

Certainly frustration with insurers is growing. According to a survey conducted last year by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health policy think-tank, in the preceding year 18% of Americans were refused care they thought would be covered, and 27% had insurers pay out less than expected. Two-fifths say that they have had to go without health care because of insurance limitations. In recent years denial rates have been rising, while insurers have adopted new tactics (such as the use of artificial intelligence to make determinations) that are deeply unpopular and have produced some shocking errors. Knowing what will be covered or denied is extraordinarily difficult, even for professionals. Around half of Americans say that they are unsure how their coverage works (see chart 1). The other half are overconfident.

Chart: The Economist

The tricky thing is that insurers are hardly the only villains in this story. UnitedHealthcare’s net profit margin is about 6%; most insurers make less. Apple, a tech giant, by contrast, makes 25%. Insurers are forced to deny coverage in large part because the firms’ resources are limited to what patients pay in premiums, sometimes with the help of federal subsidies. Yet every other part of America’s health-care system incentivises providers to overdiagnose, overprescribe and overcharge for treatment, a lot of which is probably unnecessary. Many in-demand doctors refuse to accept insurers’ rates, leading to unexpected “out-of-network” charges. Hospitals treat pricing lists like state secrets. America’s enormous health administration costs (see chart 2) are bloated by the fact that almost any treatment can lead to a combative negotiation between insurer and provider.

America has fewer doctors per capita than almost all other rich countries, and over one in four doctors earns more than $425,000. Yet a tight federal cap on residencies stops more being trained. And much treatment offered to Americans (and either paid for or refused by insurers) simply would not be offered at all in more statist countries. Mr Mangione’s back surgery is in fact a revealing case in point. The details are unclear, including whether insurance paid for his treatment. But his Reddit account suggests that he shopped around doctors before persuading one to conduct a “spinal fusion” surgery. Elsewhere, the number of such surgeries has declined over the past decade because research shows them to be ineffective compared to simpler treatments. Yet in America the number has continued to rise.

Sadly, changing health-care policy is easier to talk about than to do. And one irony of Mr Mangione’s writing is that, while it is true that American health care is expensive and often ineffective, that is not clearly linked to America’s lagging life expectancy. Indeed, one notable contributor to shorter lifespans has nothing to do with doctors. That is, the 20,000 or so murders committed each year with guns. ■

Asia | The coup that crashed

South Korea’s unrepentant president is on the brink

His attempt to impose martial law has triggered a constitutional crisis

Photograph: Getty Images

Dec 12th 2024|SEOUL

“Seoul’s spring”, the highest-grossing South Korean film of 2023, tells the story of how Chun Doo-hwan, a military dictator, seized power more than 40 years ago. It is supposed to be an edifying historical drama, a reminder of the horrors the country endured under martial law and of how far it has come in the decades since. Instead, on December 3rd, Yoon Suk Yeol, the current president, staged a real-life sequel by imposing martial law for the first time since Chun’s era. The film has shot back to the top of streaming platforms in South Korea. Mr Yoon, however, has crash landed. After quickly backtracking on the declaration of martial law, he now faces imminent impeachment or even arrest.

Mr Yoon has been defiant since his failed self-coup. He survived an impeachment vote in the National Assembly on December 7th, thanks to a boycott by his People’s Power Party (PPP). The party then proposed an “orderly” transition of power. But the dubious legality of this arrangement caused a constitutional crisis. By law, Mr Yoon remained in charge of the country and the commander-in-chief. In political and moral terms he had lost all authority.

The president underscored his unfitness for office with a raving address on December 12th, the 45th anniversary of Chun’s coup. He accused the opposition of seeking to turn South Korea into a “paradise” for foreign spies and a “drug den” overrun by “gangsters”. He railed against a “parliamentary dictatorship” that thwarted his agenda and promised to “fight until the end”. The speech came shortly after Han Dong-hoon, the head of the PPP, had changed tack and called for immediate impeachment. The Democratic Party (DP), the main opposition, will hold a vote on a second impeachment motion on December 14th. Only eight PPP members need to break ranks for it to pass.

Pressure from the streets is also building. Protest movements have been a powerful force in the country’s history, from the democratisation process in the late 1980s to the impeachment of a former president, Park Geun-hye, in 2016-17. Tens of thousands gathered on December 7th. Smaller rallies have since persisted. The mood is carnivalesque, with music, dancing and vendors selling lighting sticks intended for K-pop concerts that have been plastered with anti-Yoon slogans. But the protests are fuelled by real fury. “I’m too old to be doing this in the cold, but I’m just so angry,” says Park Ju-yeon, a 62-year-old pensioner from Seoul who promises to continue until Mr Yoon is gone.

The picture of the fateful night of the coup has become only more disturbing as details have emerged. Troops were dispatched not only to the National Assembly, but also to the national election commission. Mr Yoon says this was to gather evidence of purported North Korean hacking (which he implies led to his party’s defeat in general elections in April). The president ordered the arrests of leading politicians, including Lee Jae-myung, the head of the DP, and even Mr Han. As farcical as the affair now seems, the intent was all too serious. One special-forces commander testified that Mr Yoon personally called him during the operation and ordered him to “break down the doors” and “drag out” the lawmakers inside.

Only a small cabal, many of whom graduated from the same high school as the president, knew of the plot in advance. Rhee Chang-yong, the governor of the Bank of Korea, was among many senior officials who learned of the impending martial law only when he saw Mr Yoon on television. The declaration was so unlikely that “I initially thought the video was a deepfake and that the television station had been hacked,” says Mr Rhee.

In retrospect, signs of Mr Yoon’s intentions had been visible. In recent months he had moved loyalists into key positions in the defence ministry and intelligence services. Opposition leaders had been warning of the possibility of martial law since August. Mr Yoon’s defence minister, Kim Yong-hyun, dismissed the idea as fearmongering during his confirmation hearings. He ended up being the first official arrested in connection with the plot; he attempted suicide while in custody.

Mr Yoon’s justification for his rash act is unlikely to convince many. Mr Rhee calls the move an “unnecessary and unimaginable mistake” and an “embarrassment”. Other current and former officials, politicians and diplomats use even starker language: shameful, stupid, crazy, surreal, unthinkable, outrageous, psychotic.

Liable to be a laughing-stock

The consequences will be far-reaching. Mr Yoon positioned his country as a democratic bulwark, even co-hosting, with America, a “Summit for Democracy” in Seoul this year. He promoted the idea of South Korea as a “global pivotal state”. He has instead made it look ridiculous.

American officials insist that their alliance with South Korea remains “ironclad”. Yet trust in it may suffer, especially since America had no advance notice, despite having nearly 30,000 troops stationed there. South Korea will also be in a worse position to manage Donald Trump, America’s president-elect. A longtime sceptic of the alliance, Mr Trump discussed withdrawing American troops from the Korean peninsula during his first term. South Korea’s best hope of changing his views was for its leader to forge a personal bond, but there is likely to be a leadership vacuum in Seoul when he is inaugurated.

The political crisis may well drag on for months. If the National Assembly approves a motion to impeach, the president will be suspended, with power passing to the prime minister in the interim. The constitutional court then must issue a final ruling within 180 days. The court has just six of its nine seats filled (three justices retired in October). While only six votes are needed to convict, in normal circumstances seven would be required for a quorum. It is a matter of debate whether the court could issue a verdict in its current state.

Prosecutors may get to the president even sooner. South Korean law makes treason an exception to presidential immunity. The National Assembly voted on December 10th to empower a special counsel. Investigators have already put Mr Yoon on a no-fly list and moved to search his office.

Mr Lee, the DP’s presumptive presidential candidate, faces his own legal problems, having been convicted of lying to investigators. (He calls the charges politically motivated.) The PPP hopes that his conviction will be upheld on appeal before the next election, barring him from running. A second constitutional crisis looms if he tries to stand regardless.

Any DP candidate will be favoured to win the new elections. If they do, foreign policy will be an area of “dramatic change”, reckons Kim Sook, a former ambassador. Those changes will probably frustrate Western governments that welcomed Mr Yoon’s alignment with America, Japan and Europe. The DP may bid for more engagement with North Korea, which has been happy to sit back and watch Mr Yoon’s antics. The relationship with Japan will face friction. DP leaders are also loth to aid Ukraine or Taiwan.

The impact on South Korea’s economy will probably be more muted. “There is a mechanism for economic issues to be dealt with irrespective of political issues,” says Mr Rhee. Mr Yoon’s finance minister has agreed to take part in a consultative body for emergency economic policymaking alongside the DP. Daily life has continued without interruption since the abortive martial-law attempt. Acute turbulence on financial markets proved short-lived. But prolonged political uncertainty will make it harder to tackle longer-term economic challenges. A DP president will want to implement labour-friendly policies, while corporate-governance reforms that Mr Yoon promoted may stall.

For all the turmoil, the incident has also highlighted the evolution and resilience of South Korea’s democracy. During Chun’s rule, Ms Park, the pensioner, and her husband, Hyeong-Bae, were too afraid to protest. Previous periods of upheaval, including the massacre of protesters by Chun’s forces in Gwangju in 1980, helped strengthen South Koreans’ dedication to democracy. “I hope this will be another of those episodes that feeds into that process,” says Mr Park. The film version, when it inevitably gets made, will write itself. ■

China | Language lessons

Why China is losing interest in English

Learning the world’s lingua franca is no longer a priority for students or businessmen

Photograph: Getty Images

Dec 12th 2024|BEIJING

IN PREPARATION FOR the summer Olympics in 2008, the authorities in Beijing, the host city and China’s capital, launched a campaign to teach English to residents likely to come in contact with foreign visitors. Police, transit workers and hotel staff were among those targeted. One aim was to have 80% of taxi drivers achieve a basic level of competency.

Today, though, any foreigner visiting Beijing will notice that rather few people are able to speak English well. The 80% target proved a fantasy: most drivers still speak nothing but Chinese. Even the public-facing staff at the city’s main international airport struggle to communicate with foreigners. Immigration officers often resort to computer-translation systems.

For much of the 40 years since China began opening up to the world, “English fever” was a common catchphrase. People were eager to learn foreign languages, English most of all. Many hoped the skill would lead to jobs with international firms. Others wanted to do business with foreign companies. Some dreamed of moving abroad. But enthusiasm for learning English has waned in recent years.

According to one ranking, by EF Education First, an international language-training firm, China ranks 91st among 116 countries and regions in terms of English proficiency. Just four years ago it ranked 38th out of 100. Over that time its rating has slipped from “moderate” to “low” proficiency. Some in China question the accuracy of the EF index. But others note that this apparent trend is happening when China is also growing more insular.

During the covid-19 pandemic, for example, China shut its borders. Officials and businessmen, let alone ordinary citizens, made few trips abroad. Long after the rest of the world began opening up, China remained closed. At the same time, China’s relations with the world’s biggest English-speaking countries soured. Trade wars and diplomatic tiffs strained its ties with America, Australia, Britain and Canada.

The mood is such that legislators and school administrators have tried to limit the amount of time devoted to the study of English, and to reduce the weight given to it on China’s all-important university-entrance exams. In 2022 a lawmaker proposed de-emphasising the language in order to boost the teaching of traditional Chinese subjects. The education ministry demurred. But a professor at one of China’s elite universities says many students consider English less important than it used to be and are less interested in learning it.

As China’s economy slows, people have become more cautious and inward-looking. Today fewer Chinese are travelling abroad than before the pandemic. Young people are less keen on jobs requiring English, choosing instead to pursue dull but secure work in the public sector.

Then there are translation apps, which are improving at a rapid pace and becoming more ubiquitous. The tools may be having an effect outside China, too. The EF rankings show that tech-savvy Japan and South Korea have also been losing ground when it comes to English proficiency. Why spend time learning a new language when your phone is already fluent in it? ■

China | China and America

MAGA with Chinese characteristics

Why many in China cheer for Donald Trump, despite his tariffs and team of hawks

Illustration: Ben Hickey

Dec 9th 2024|BEIJING

THE INTERNET in China is not a friendly place for admirers of anything American. Fire-breathing nationalists, helped by censors who are quick to stamp out liberal views, rule the roost. Yet as China digests the implications of Donald Trump’s re-election as president, including his threat of huge tariffs on Chinese goods, many netizens see in him something to like. In their own world of economic anxiety and yawning social divides, strands of the MAGA movement seem familiar. China’s nationalists can be surprisingly Trumpian. Some of them are even pro-Trump.

To be sure, many of those who cheer for Mr Trump do so out of contempt for America. They share clips of his moments of buffoonery and sneer at his nominations for cabinet posts—don’t they prove what a sham democracy is, with jobs so flagrantly doled out to loyalists regardless of their suitability? The nationalists relish the thought that Mr Trump might weaken American support for Taiwan or end military aid for Ukraine. They refer to him by a nickname: Chuan Jianguo, meaning “Trump the Nation Builder”. It is supposed to be ironic—they mean he is making China stronger by undermining America.

But China’s nationalists also genuinely admire aspects of Mr Trump. They like his strongman image and the conservative social views he professes. “There are many lessons to be learned by our government departments about Trump’s coming to power,” wrote a doctor, Ning Fanggang, who has nearly 1.6m followers on the microblogging site Weibo and supports attacking Taiwan as well as condemning LGBT activism. “The most important takeaway is this: loud voices do not necessarily represent the true will of the people,” he said, referring to Democrats’ backing for LGBT rights. “Trump’s election revealed that the vast majority of ordinary people were opposed to those ideas deep down.”

In recent weeks Chinese nationalists have expressed outrage at a video showing Jin Xing, a transgender celebrity, raising a rainbow flag at a performance (Ms Jin was once a male colonel in a Chinese army dance troupe). They have also applauded Mr Trump’s campaign speeches on trans issues. A Weibo user with more than 700,000 followers posted a clip of one of them, in which Mr Trump pledged to “defeat the toxic poison of gender ideology”. Ms Jin and people like her, said the blogger, “must be hopping mad with rage”. Commenters agreed. “This is why I don’t want Trump to win,” said one. “Only Harris can make America even worse.”

Many of the nationalists brush off Mr Trump’s talk of imposing tariffs of 60% on Chinese goods. One of them is Ren Yi, a Harvard-educated princeling (as descendants of powerful politicians are known). Mr Ren goes by the name “Chairman Rabbit” on social media (his Weibo followers number more than 1.8m). He tells The Economist that Mr Trump’s instincts are not necessarily anti-China.

For example, he notes, the president-elect has suggested that he would reverse a ban on TikTok, a Chinese-owned video-sharing app, and invite Chinese carmakers to do business in America. The tariff talk is just a tactic, Mr Ren believes: Mr Trump might change his mind if Chinese companies invest in America. Mr Ren and other nationalists see promise in Mr Trump’s close associate, Elon Musk, whose car firm, Tesla, makes more than half of its vehicles in China. Some of Mr Trump’s picks for government posts may be China hawks, but others, like Mr Musk, seem to be “much more open” to China, Mr Ren says.

A particularly vocal group of nationalists is known as xiaofenhong, or “little pinks”. These young, fiercely patriotic netizens are not the kind of people who, in America, would be thought of as typical Trump supporters. Chinese academics say the pinks are often well educated and urban. The original little pinks were mainly young women, though the group is now more diverse. As with MAGA types in America, the main targets of their discontent are liberals at home, such as Ms Jin.

Public opinion in China is polarised. Culture wars rage, just as they do in America. Some nationalists share the misogynist worldview of young men in the West known as “incels” (involuntary celibates), who blame their inability to form sexual relationships on supposedly over-empowered and picky women. In China, such people sometimes self-deprecatingly call themselves diaosi, which literally means “dick hair”. They do endless battle online with China’s equally fiery feminists.

Cyber-liberals point out the irony of their opponents’ pro-Trump views. “Some so-called ‘little pinks’ and patriotic bloggers on Weibo spend their days opposing feminism and LGBT rights, demonising the left, and end up idolising one extreme anti-China, deranged right-winger after another,” wrote a Weibo user who has more than 390,000 followers after Mr Trump’s victory.

Pro-Trump sentiment, however, will not persuade China’s leader, Xi Jinping, to be better disposed towards America’s next president. Mr Xi shares the nationalists’ views on social values. And he would doubtless love it if Mr Trump were to prove as transactional on Taiwan, and as unsympathetic to Ukraine, as his supporters in China hope he will be.

But Mr Xi is surely anxious about Mr Trump’s return. It will make China’s relationship with America more unpredictable. It could also—if Mr Trump’s threatened tariffs do indeed materialise—further damage China’s struggling economy. America’s election may even have reminded the stability-obsessed Mr Xi of something the little pinks may be wary of saying out loud: citizens embittered by economic malaise can turn against elites. ■

Middle East & Africa | Getting away with murder

Kenyan women are fed up with rampant sexual violence

A spate of horrific murders has fuelled a campaign to end femicide

Taking the fight to the streetsPhotograph: Getty Images

Dec 12th 2024|Nairobi

Each fresh killing seems more gruesome than the last. In July the hacked-up remains of nine women were found stuffed into sacks in a quarry in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital. In September Rebecca Cheptegei, a Ugandan Olympic runner who was living in Kenya, was doused in petrol and set on fire by her estranged boyfriend. And in October police found the remains—apparently boiled, flesh methodically removed—of a female body near a cemetery in Nairobi.

Kenyan women have had enough of the grim routine. Back in January 10,000 protesters took to the streets of Nairobi, after at least 31 women were killed in a single month. The protest sparked a sustained campaign to “end femicide”. Activists want the government to make the murder of a woman or a girl because she is female a specific crime. But misogynistic social-media influencers are stoking hate against women online. And there are signs that the violence is getting worse.

Campaigners have had some success highlighting the problem. A new survey by the Ichikowitz Family Foundation, a South African charity, finds that 95% of young Kenyans are worried about violence against women, a higher proportion than in any other country in Africa bar South Africa. Several MPs say that femicide should be declared a national disaster.

Yet a reduction in violence looks far off. A study by Africa Data Hub, a research group in Nairobi, counted more than 500 reports of femicide in the Kenyan media between 2016 and 2023, with a sharp spike between 2022 and 2023. The real number is likely to be much higher. Many crimes in Kenya are never reported to the police; only the most heinous killings make the news. “We can assume this is just the tip of the iceberg,” says Irungu Houghton of Amnesty International, a human-rights group.

If anything, things seem to have worsened in 2024. The number of reported rapes has increased by 40% compared with 2023, according to the government’s latest national-security report (though some of this may be down to improved reporting). Kenya’s deputy police chief notes 97 women were murdered in just the three months up to November, though it is unclear how many were killed on account of their sex. “Every single day you wake up and a woman has been killed somewhere,” says Muthoni Maingi, a leading campaigner.

Change is likely to be slow. In Kenya, as in many African countries, patriarchal values are entrenched. According to the latest demographic and health survey, more than a third of Kenyan women have experienced violence. Some 13% have experienced sexual violence. As elsewhere, the main perpetrators are intimate partners. Three-quarters of femicides counted by Africa Data Hub were committed by men who knew their victims.

Economic trends may have made things worse. In 2020, when covid-19 lockdowns slowed the economy, incidents of violence against women went up by more than 90%, according to Kenya’s National Crime Research Centre. Since then the economy has struggled; 67% of those under the age of 34 have no regular job. For men for whom “money is connected to his status as a man”, economic frustration may make them lash out against women in their lives, says Onyango Otieno, another activist.

Male anger is also being stoked online. A network of misogynistic influencers has exploded in recent years. Figures such as Amerix (whose real name is Eric Amunga) and Andrew Kibe boast huge followings of young men, to whom they offer advice on how to be “real men” and control their wives and girlfriends. Though no direct link can be drawn between individual murders and specific online influencers, Kenya’s “manosphere” “rationalise[s] women’s murders as part of disciplining women back into their traditional roles,” argues Awino Okech of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

On December 10th women were back on the streets of Nairobi. They expect little from the government. The dispiriting truth, says Wangui Kimari, an academic, is that in Kenya “it is easy to kill a woman, and get away with it.” ■

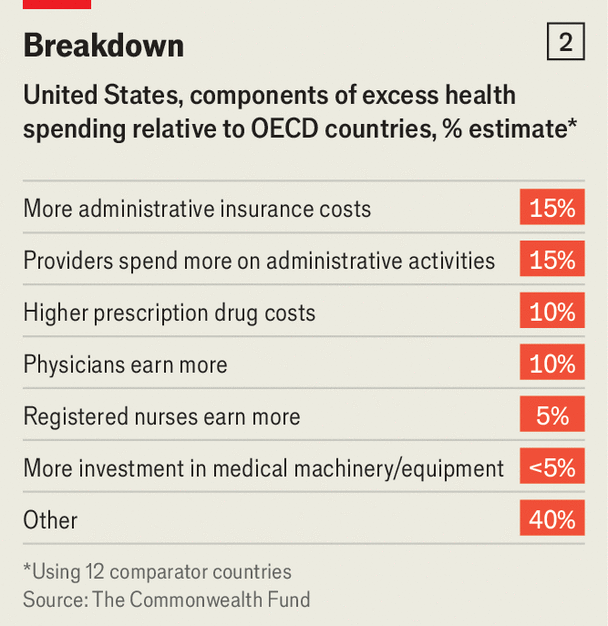

Middle East & Africa | Back in the dock

Binyamin Netanyahu is in court again in Israel

As he fights charges of corruption, his country’s democracy may suffer

Photograph: AP

Dec 12th 2024|Tel Aviv

The small but noisy groups of protesters shouting at each other outside the Tel Aviv District Court on December 10th agreed on one thing. It was absurd for the man running a country, with wars on several fronts, to spend three days a week in court defending himself against complex corruption charges. Critics of Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s first serving prime minister to appear as a witness in his own defence in a criminal trial, think he should resign and face his manifold legal challenges as an ordinary citizen.

His supporters, however, are convinced he is indispensable. They consider the whole case a witch-hunt that should be called off. As for Mr Netanyahu, in recent weeks he has tried in vain to get a security assessment that it was dangerous for him to attend court at fixed times in the same place. Then he said he had too little time to prepare his testimony. Finally, he denied ever having tried to delay the show. “I’ve waited eight years for this moment,” he told the court. “I’m a marathon-runner” who can prevail “with 20kg on my back”.

The investigations into Mr Netanyahu’s affairs began in 2016. Charges of fraud and bribe-taking were laid against him five years ago. He is accused of accepting illicit gifts from rich benefactors and colluding with media barons to get favourable coverage. He strenuously denies all the charges.

At the start of his testimony Mr Netanyahu claimed that what the media say about him “is not really important”, then went on to explain in detail how journalism in Israel works and defended his meetings with publishers and editors to influence journalistic appointments.

The case has dragged on so long for many reasons, including covid-19, the war against Hamas since October 7th 2023, delaying tactics by Mr Netanyahu’s defence team, and the slow pace of Israel’s courts. Judges are overloaded partly because Mr Netanyahu’s coalition has tried to change the judicial-appointments system and, having failed to do so, has been obstructing the existing process.

Mr Netanyahu’s legal travails have been responsible for forcing the country to hold five elections in four years, as centrist parties have refused to join a government led by an indicted prime minister. In 2021 he lost power for 18 months but came back at the end of 2022 with a coalition supported by far-right and religious parties that share his hostility to Israel’s courts.

The ambitious judicial reforms that he promoted last year aimed to weaken the Supreme Court and independent legal counsel to government but were largely stymied by a massive wave of protest. They were then dropped in the name of national unity after last year’s war in Gaza began.

But in recent months his government has restarted the campaign to increase control of parts of the state. This includes laws now going through the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, that would let politicians fire the attorney-general and control the appointments of the commissioner of the civil service and of the ombudsman investigating complaints against judges. Other laws would grant members of parliament virtual immunity from investigation and would defund or privatise Israel’s stubbornly independent broadcasting corporation. In his autobiography in 2022 Mr Netanyahu says he has “always been a staunch believer in liberal democracy” and been “immersed since my teens in its classical texts”. That assertion may be tested under cross-examination by the prosecution.

Mr Netanyahu is the first of many witnesses for the defence. It could be years before a verdict is reached. But Israel’s courts have held Israeli leaders to account before. Ehud Olmert, a former prime minister, was jailed for bribery. Mr Netanyahu is determined to avoid that fate. But by clinging to power by every means, he may undermine Israel’s democracy. ■

Europe | La excepción

Spain shows Europe how to keep up with America’s economy

Reforms a decade ago are bearing fruit with high-tech success

Photograph: dpa

Dec 12th 2024|Madrid

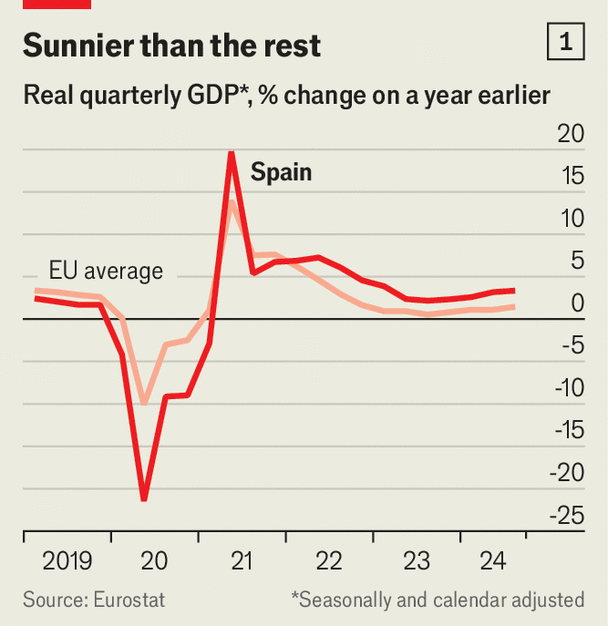

“Spain is becoming a global reference point for prosperity,” boasted Pedro Sánchez, the country’s prime minister, at a congress of his Socialist Party in Seville on December 1st. While Europe’s other large economies are plunged in gloom, Spain’s is soaring. It is set to grow 3% this year (see chart 1), almost four times the euro-area average. Hit harder than most by the pandemic, it now boasts 1.8m more jobs than at the end of 2019. Investors have noticed: with faster growth and a lower fiscal deficit than France, Spain has seen its bond yields dip below those of its northern neighbour for the first time since 2007.

With packed restaurants and throngs of shoppers, Madrid is enjoying a palpable pre-Christmas buzz. But how long can the good times last? Forecasters expect Spain to outpace its peers for at least the next two years, helped in part by large dollops of Next Generation funds, the European Union’s post-pandemic aid scheme. The country is the biggest beneficiary of these after Italy. Much of the expansion has been driven by immigration, tourism and public spending, which may all eventually tail off. But some of the growth comes from non-tourist service exports, by companies ranging from tech firms to engineering consultants. And that bodes well.

Chart: The Economist

Take Smartick, an educational software company based in Pozuelo, a well-heeled suburb of Madrid. It uses big data and AI to provide pupils with individualised learning materials in maths, reading and coding. Founded in 2009 by Javier Arroyo and a fellow management consultant, it is poised for growth. Mr Arroyo expects to double the firm’s €10m ($10.5m) of annual sales in three years, with most of the expansion coming from abroad. “There’s now a startup culture that wasn’t there five or ten years ago,” Mr Arroyo says. “Spain is starting to figure in the digital world.”

During the pandemic, non-tourism service exports overtook tourism revenues for the first time. But the travel sector is booming too, with over 90m visitors expected this year, a record. That has produced outbreaks of tourism phobia among locals.

The tourism boom is also one of the reasons for immigration: a quarter of those who work in hospitality are foreign-born. Spain’s population has increased by 1.5m in the past three years (to 48.9m), with nearly all the increase due to immigration (see chart 2). Latin Americans, with the same language and a similar culture, make up 70% of the recent arrivals, which has reduced friction. Whether immigration can continue at this pace depends in part on the availability of housing. “It’s a bigger bottleneck than ever,” says Rafael Domenech of BBVA, a bank.

Chart: The Economist

But with around 90% of the new jobs going to immigrants, income per person has barely grown. That explains a paradox: “The macroeconomic picture is extraordinary but the social perception of it is not,” says Raymond Torres of Funcas, a think-tank. Although the inflation triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has subsided, in real terms the income of a family who stayed in the same jobs is slightly below that of 2019. Only in the past year or so have average real wages started to rise. Officials point out that thanks to Mr Sánchez’s big increases in the minimum wage, the incomes of poorer Spaniards have risen faster than the average.

Worryingly, investment by the private sector lags behind the rest of the economy. It is still below its 2019 level. Until the pandemic interrupted it, Spain’s economy was growing at a respectable 3% or so a year between 2015 and 2019 and adding jobs faster than in the past. This owed much to reforms of the financial system and the labour market pushed through by the previous conservative government during the great recession. “Spain is still living from that,” says Iñigo Fernández de Mesa of the employers’ association.

A second labour reform in 2021, under Mr Sánchez, preserved labour flexibility and added a crackdown on the abuse of temporary contracts. But business leaders blame the slowdown in investment on more recent government policies. They complain especially of constant tinkering with labour rules and a relentless rise in taxes. As a result, “businesses are on hold, waiting,” says Juan María Nin of the Circulo de Empresarios, a business think-tank.

Since an election last year, Mr Sánchez’s minority government has had to accommodate the conflicting demands of half a dozen leftist and nationalist parties which sustain it in parliament. Amid chaotic parliamentary scenes last month, it managed to get approval for tax rises worth €4.5bn (0.3% of GDP). They include an extension for three years of an emergency tax on the interest and fee income of banks, initially brought in as a temporary measure when interest rates rose in 2022. Bankers grumble that this involves double taxation and will force banks to become more cautious in granting credit.

Officials note that banks and businesses are making healthy profits. The bank tax “has generated revenues to finance the social safety-net”, says Carlos Cuerpo, the economy minister. He says he expects investment and private consumption to be the main motor of growth from now on. The tax rises will also help the government meet its policy of gradually reducing the fiscal deficit and thus secure the next tranche of EU aid. “We think a soft landing is possible,” says Mr Cuerpo. That may well be true for the public finances. The proof of the Spanish model more broadly now lies in the rate of investment. ■

International | The Telegram

The Art of the Deal: global edition

Donald Trump will have vast leverage over American allies, but ruthless despots may resist his dealmaking

Illustration: Ellie Foreman-Peck

Dec 10th 2024

WITH THE right portfolio of assets, property developers enjoy tremendous power over architects, builders and potential tenants. Yet even the richest have little leverage over arsonists.

That bricks-and-mortar framing is surprisingly helpful for understanding why America’s next president is both right and wrong about his ability to reshape the global order. The Telegram is willing to risk a prediction: in his second presidency, Donald Trump will wield tremendous power over allies and countries that profit from ties with America. With adversaries ready to burn relations with the West to the ground, his grip will be less sure.

Mr Trump sounds confident that he has leverage on all fronts. Big economic partners, whether that means Canada, China, the European Union or Mexico, have been warned to brace for tariffs on their exports, followed by calls to renegotiate terms of trade with America. At the same time, Mr Trump has pledged to end Russia’s war with Ukraine within 24 hours. He has warned Hamas to release hostages taken in Israel on October 7th 2023, or face being “hit harder than anybody has been hit in the long and storied history of the United States of America”.

The strengths and limits of this approach are apparent to American and foreign officials who watched Mr Trump’s first presidency up close. It is striking how often the same insiders draw lessons from his career building casinos, hotels and golf courses. Indeed, go back to interviews that Mr Trump has given over many years, and he sometimes makes America’s economy sound like the world’s most valuable bit of real estate. Because he thinks previous American presidents were “suckers” who let foreign partners pay too little for access to it, he is ready to impose aggressive rent reviews.

In Mr Trump’s first presidency, numerous allies endured his dealmaker’s scrutiny. This was often a humiliating experience. In June 2017 Panama’s then-president, Juan Carlos Varela, secured a meeting in the Oval Office, a visit liable to boost him with voters back home. During their encounter, Mr Trump questioned why American warships pay to use the Panama Canal, which returned to Panamanian control in 1999. Mr Trump told his Panamanian guest that surrendering the canal zone was a terrible deal and that “we should take that thing back”, recalls America’s then-ambassador to Panama, John Feeley. To his relief the Panamanian leader, whom he had “assiduously prepped” to avoid confronting Mr Trump at all costs, tactfully changed the subject, Mr Feeley says. Mr Varela asked his host: “Mr President, can I ask you a question? How are you doing in Syria?” (America is winning, he was told.)

Another former American official watched Mr Trump bullying a string of allies, and draws links to his business career. As a developer, Mr Trump routinely told suppliers to lower their prices after they had completed projects. Some sued. Others wanted future business so gave in. “He always stiffed his subcontractors,” notes that eyewitness. “To him, allies are like subcontractors.”

Many times, Mr Trump’s “unconventional thinking cut to the quick of things”, the former official goes on. Mr Trump asks “very good questions” and was “a wrecking ball to things that needed to be disrupted”. He had a patchier record when it came to building sturdier alternatives. Too often, his ambitions were thwarted by his impatience with detail, and by his struggles to understand foreign leaders guided by incentives very different from his own.

For all his tough talk, Mr Trump wants to be loved, seeing himself as a man of destiny sent to protect ordinary Americans’ interests, says the former official. He craves the approval of financial markets and of very rich people, whose wealth he takes as a proxy for brilliance. Truly cold-blooded rulers confound him. “Someone who is utterly ruthless, and who will slaughter anyone they need to, Trump can’t get his head around that.” In his first presidency, the businessman was “totally shocked” by intelligence briefings about Syria’s then-dictator, Bashar al-Assad, using poison gas on women and children in his own country. In contrast, the same former official watched Mr Trump failing to fathom leaders who acted on humanitarian impulses, as when Germany’s then-chancellor, Angela Merkel, told him she had allowed Syrian refugees into her country because it was the right thing to do.

Not everyone wants to build beach resorts

Those same blind spots could become apparent once more when Mr Trump returns to office. President Vladimir Putin is willing to sacrifice terrible numbers of Russian lives to keep pushing deeper into Ukraine. Given that the Russian leader is currently winning ground while Ukraine suffers a crisis of manpower and morale, some Western officials wonder why Mr Trump imagines he can force Russia to stop the war soon. Trumpian threats to strike Hamas are equally unconvincing, for that terrorist group is willing to see Gaza destroyed to advance its fanatical goals.

A former Western diplomat says that Mr Trump placed excessive faith in economic incentives, as when he left an Obama-era pact to constrain Iran’s nuclear programme, the JCPOA, in 2018. Trump aides told allies that their builder-boss saw the pact as an edifice with bad foundations, fit only for demolition. The JCPOA was imperfect, agrees the former diplomat. Still, it imposed real curbs on Iran and Mr Trump’s rebuilding plan was worse: he asserted that harsher sanctions would swiftly bring Iran to its knees, leaving its rulers begging for a new deal. This did not happen. Nor was North Korea’s hereditary despot, Kim Jong Un, swayed by Mr Trump’s invitation to abandon nuclear arms and develop his country’s beaches for tourism. To the former diplomat, Mr Trump is constrained twice over: by his “vast lack of knowledge about abroad” and by his instinct that America should disengage from foreign wars. In a world on fire, the art of the deal has limits. ■

Business | Bartleby

The employee awards for 2024

Least accurate website photo. Best AI-washer. Let’s celebrate our winners

Illustration: Paul Blow

Dec 12th 2024

It’s that time of year again, when we celebrate our successes and gloss over our failures. For our 2024 employee awards we have all our classic categories, from team member of the year and newcomer of the year to the big one: employee of the year. As usual, the winner of that award will enjoy a weekend away in a location of our choosing.

But first, we have taken on board last year’s criticisms that these awards have an overly traditional view of achievement. We are fully committed to inclusivity and have introduced several new categories this year to reflect the extraordinary range of contributions that all of you make. Please join me in congratulating our debut winners.

Most likely to make an irrelevant point. There was enormous competition in this category; several people who took part in the judging process ended up coming close to winning. But we’d like this to go to Violet. None of us could recall a discussion when she had not made a point; none of us could remember a time when that point was salient.

Least punctual colleague. We used actual data to track arrivals in virtual meetings. We can see that Akshat arrives 12 minutes late on average, which is enough to earn him a commendation. But the winner is someone called Mandy, who did not turn up to a single meeting to which she was invited. We are currently trying to work out who this person is and why no one has ever heard of her.

Least accurate website photo. Again, a very hotly contested category. A few colleagues appear to be using their passport photos: they are doing themselves a disservice. But most people look younger, friendlier and more attractive than they actually are. The prize in this category goes to Paul, who resembles a promising young novelist on the site and looks like a repeat offender in real life.

Most likely to nominate themselves for an award. This (self-nominated) category honours those who know the value of self-promotion and struggle with irony. We think this category may well be a reliable guide to spotting our leaders of tomorrow. So well done, Willem.

Source of greatest uncertainty over what they actually do. All of our senior leadership team received lots of nominations. So did the marketing and HR departments. But the clear winner is the strategy office. No other team received more nominations from its own members than this one, which is surely an achievement worth marking.

Most disliked item of clothing worn by a co-worker. We can’t get any of you to answer the employee survey except through veiled threats. But give people permission to weigh in on how their colleagues dress and suddenly everyone has a view. Overly tight T-shirts, sweaters with holes in them, weirdly jaunty scarves, those terrible trousers: they all featured. But in the end no one wanted to look beyond, or at, Bogdan’s shorts.

Longest co-working relationship without conversation. Sylvie and Edgar have been colleagues for 19 years and have recently only moved to nodding terms. They are both gearing up to say “hello” to each other some time in 2032, and we’ll keep a very close eye on their progress. Well done, both of you.