The Economist Articles for June. 1st week : June. 1st(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.05.23조회수115 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for June. 1st week : June. 1st(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Vietnam

The man with a plan for Vietnam

A Communist Party hard man has to rescue Asia’s great success story

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

Fifty years ago the last Americans were evacuated from Saigon, leaving behind a war-ravaged and impoverished country. Today Saigon, renamed Ho Chi Minh City, is a metropolis of over 9m people full of skyscrapers and flashy brands. You might think this is the moment to celebrate Vietnam’s triumph: its elimination of severe poverty; its ranking as one of the ten top exporters to America; its role as a manufacturing hub for firms like Apple and Samsung. In fact Vietnam has trouble in store. To avoid it—and show whether emerging economies can still join the developed world—Vietnam will need to pull off a second miracle. It must find new ways to get rich despite the trade war, and the hard man in charge must turn himself into a reformer.

That man, To Lam, isn’t exactly Margaret Thatcher. He emerged to become the Communist Party boss from the security state last year after a power struggle. He nonetheless recognises that his country’s formula is about to stop working. It was concocted in the 1980s in the doi moi reforms that opened up the economy to trade and private firms. These changes, plus cheap labour and political stability, turned Vietnam into an alternative to China. The country has attracted $230bn of multinational investment and become an electronics-assembly titan. Chinese, Japanese, South Korean and Western firms all operate factories there. In the past decade Vietnam has grown at a compound annual rate of 6%, faster than India and China.

The immediate problem is the trade war. Vietnam is so good at exporting that it now has the fifth-biggest trade surplus with America. President Donald Trump’s threat of a 46% levy may be negotiated down: Vietnam craftily offered the administration a grab-bag of goodies to please the president and his allies, including a deal for SpaceX and the purchase of Boeing aircraft. On May 21st Eric Trump, the president’s son, broke ground at a Trump resort in Vietnam which he said would “blow everyone away”.

But even a reduced tariff rate would be a nightmare for Vietnam. It has already lost competitiveness as factory wages have risen above those in India, Indonesia and Thailand. And if, as the price of a deal, America presses Vietnam to purge its economy of Chinese inputs, technology and capital, that will upset the delicate geopolitical balancing act it has performed so well. Like many Asian countries it wants to hedge between an unreliable America and a bullying China which, despite being a fellow communist state, has long been a rival and now disputes Vietnam’s claim to coastal waters and atolls. The trade and geopolitical crunch is happening as the population is ageing and amid rising environmental harm, from thinning topsoils in the Mekong Delta to coal-choked air.

Mr Lam made his name orchestrating a corruption purge called “the blazing furnace”. Now he has to torch Vietnam’s old economic model. He has set expectations sky-high by declaring an “era of national rise” and targeting double-digit growth by 2030. He has made flashy announcements, too, including quadrupling the science-and-technology budget and setting a target to earn $100bn a year from semiconductors by 2050. But to avoid stagnation, Mr Lam needs to go further, confronting entrenched problems that other developing countries also face as the strategy of exporting-to-get-rich becomes trickier.

Vietnam’s growth miracle is concentrated around a few islands of modernity. Big multinational companies run giant factories for export that employ locals. But they mostly buy their inputs abroad and create few spillovers for the rest of the economy. This is why Vietnam has failed to increase the share of the value in its exports that is added inside the country. A handful of politically connected conglomerates dominate property and banking, among other industries. None is yet globally competitive, including Vietnam’s loss-making Tesla-wannabe, VinFast, which is part of the biggest conglomerate, Vingroup. Meanwhile, clumsy state-owned enterprises still run industries from energy to telecoms.

To spread prosperity, Mr Lam needs to level the playing field for smaller firms and new entrants. That means hacking back a bewildering licensing regime and allowing credit to flow to small firms by shaking up a corruption-prone banking industry. Legislation issued this month abolishes a tax on household firms and strengthens legal protection for entrepreneurs. That is a step in the right direction, but Mr Lam also needs to free up universities so that ideas flow more easily and innovations thrive.

This is where it gets risky. Vietnam’s people would without a doubt benefit from a more liberal political system. But although that may also help development, China has shown that it may not be essential—at least not immediately. What is crucial is facing down powerful vested interests that hog scarce resources. A good start would be forcing the oligarchs to compete internationally or lose state support, as South Korea did with its chaebols. Often they are protected by cronies and pals within the state apparatus and the Communist Party. Encouragingly, Mr Lam has already begun a high-stakes streamlining of the state, including by laying off 100,000 civil servants. He is also halving the number of provinces in a country where regions have sponsored powerful factions within the party. And he is abolishing several ministries. All this will modernise the bureaucracy, but it is also a brilliant way of making enemies.

The autocrat’s dilemma

The danger is that, like Xi Jinping in China, Mr Lam centralises power so as to renew the system—but in the process perpetuates a culture of fear and deference that undermines his reforms. If Mr Lam fails, Vietnam will muddle on as a low-value-added production centre that missed its moment. But if he succeeds, a second doi moi would propel 100m Vietnamese into the developed world, creating another Asian growth engine and making it less likely that Vietnam will fall into a Chinese sphere of influence. This is Vietnam’s last best chance to become rich before it gets old. Its destiny rests with Mr Lam, Asia’s least likely, but most consequential, reformer. ■

Asia | Do it with conviction

How to fix India’s sclerotic justice system

There are plenty of ideas but not enough action

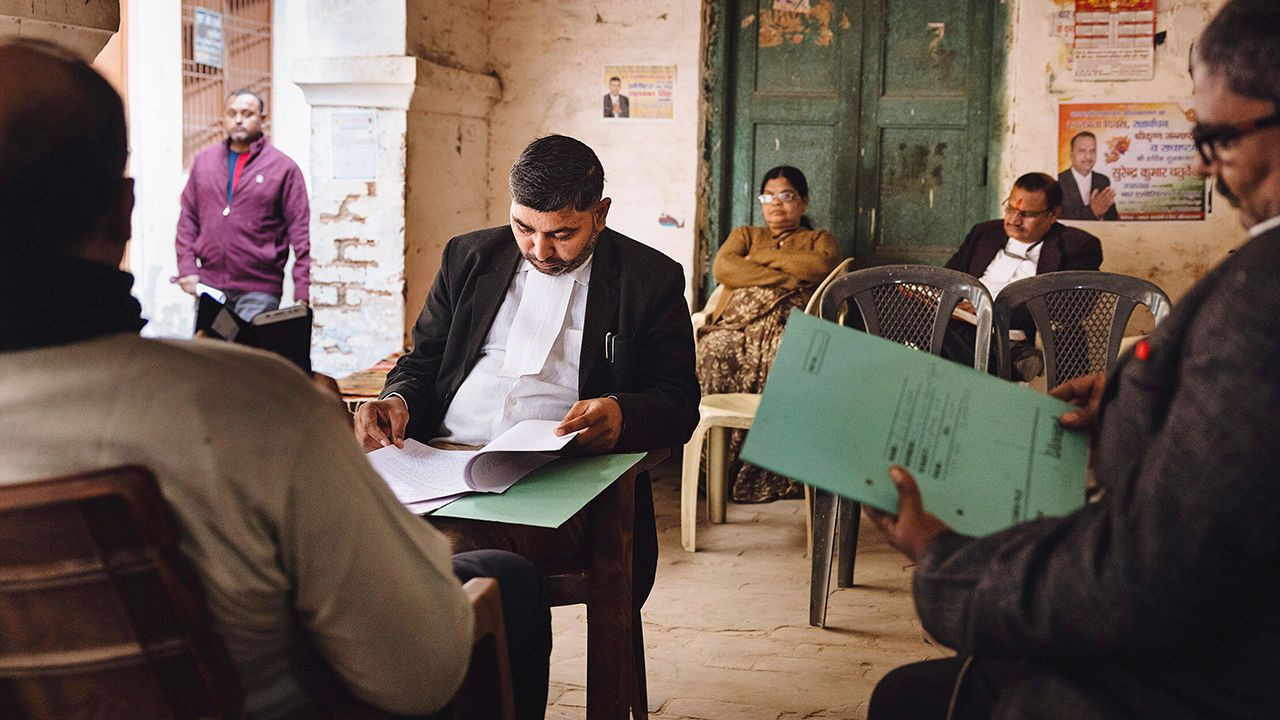

Photograph: Elke Scholiers/The New York Times)/Redux/Eyevine

May 22nd 2025|Delhi

Listen to this story

In most faiths judgment is delivered in the afterlife. India’s judiciary seems to have adopted a similar approach. Earlier this year in the central city of Bhopal, a newspaper revealed that a case filed in 1959 was still winding its way through a local court—despite the accused and witness having died many years ago. For Bhushan Gavai, the Supreme Court judge who was appointed as India’s chief justice on May 14th, this is a familiar problem that has vexed all his predecessors.

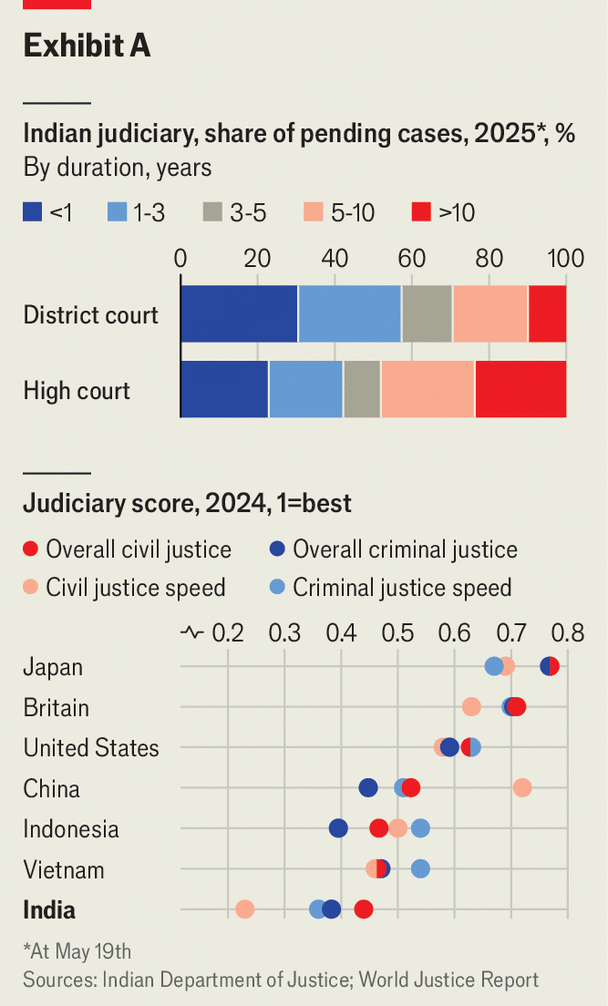

India’s judicial system is painfully slow. Across the country more than 50m cases are awaiting a verdict. Of those, nearly a third have been pending for more than five years (see chart), while around half have been delayed by at least three years. Outside a district court in Saket, a suburb of Delhi, Seema Chauhan, a 34-year-old, arrives for a hearing in a domestic-violence case, only to find out that there has been an adjournment from the judge for a later date. But for Ms Chauhan, that is not news: her case started in 2016.

Chart: The Economist

All this has meant India has consistently fared worse on composite measures of justice than several of its peers, including Indonesia, China and Vietnam, according to the World Justice Project, a research outfit. On a specific indicator of judicial speed, India ranked 131st out of 142 countries, below Pakistan and Sudan. According to the India Justice Report, a non-profit, the courts’ backlog is expected to increase by at least 15% by 2030. India’s judiciary is not in a “mere state of stasis but a downward spiral”, says Gautam Patel, a former judge of the Bombay High Court.

Several factors explain the judiciary’s malaise, but they all are rooted in weak management. At every level, judges are hindered by archaic rules. Mr Gavai, the new chief justice, will only have six months in his role before mandatory retirement rules force him out. His successor will only enjoy the post for less than three months. Mr Patel, the former high court judge, complains that he has had to assess district judges on their punctuality and courteousness, despite never seeing them in court.

The judiciary is also overworked and understaffed. Nearly a third of judge positions and a quarter of support staff roles in high courts are vacant. But filling vacancies alone is not enough. Even at full strength, the caseload would never be cleared because of new cases constantly being filed. In 2024 the lower courts disposed of 23m cases, even as 25m were added. Our calculations suggest clearing the backlog would also require a 40% productivity increase, sustained over five years.

The consequences of this malaise are vast. Around 75% of India’s prisoners are awaiting trial, the sixth-highest share in the world. Judicial delays also have enormous economic impact. In addition to legal expenses, people like Ms Chauhan face the opportunity cost of forgone wages. These alone amount up to at least 0.5% of GDP in a year, according to work by DAKSH, an Indian legal think-tank.

Firms are even bigger economic victims. Many are dragged into long disputes, often over basic contracting issues. In 2019 the World Bank estimated that enforcing a contract in India can take roughly 1,500 days (a little less than four years), compared with less than 500 in the rich world and China. India’s courts are no longer an instrument for resolving disputes between parties, but one for buying time, says Arghya Sengupta, founder of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, another think-tank.

Clogged-up courts could lead to corruption. In March, officials responding to a fire at the house of Justice Yashwant Varma, a judge in Delhi’s High Court, discovered among the burnt items currency notes worth 150m rupees ($1.8m). Mr Varma is under investigation by the Supreme Court for possible corruption, but denies any impropriety. Critics, however, think that graft thrives in dysfunctional systems.

One solution is to outsource the court’s administrative work away from judges to management specialists. Other countries with similar common-law systems, such as Australia, Britain and Canada, have used agencies to improve judicial performance. In Kenya, reforms introduced in 2011—which instructed judges to organise more pre-trial conferences and set case deadlines—have reduced the country’s backlog. Crucially, such reforms do not require constitutional changes, nor do they compromise the judiciary’s independence.

Another solution, which has been implemented, is specialised courts. But these too are already burdened with the same problems. For instance, more than 200,000 cases, involving claims of at least 18trn rupees, are piled up in various debt-recovery tribunals across the country. Meanwhile alternative dispute mechanisms, such as arbitration and mediation, that let parties settle matters between themselves outside court, are still under-developed.

Defining independence

Little has changed because judicial delays are not a big political issue, according to Dr Sengupta. “We’ve long assumed courts will manage themselves,” he says. In 2014 the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) tried to involve the government in judicial appointments, which are controlled entirely by the courts and long considered opaque. The BJP’s proposal triggered a backlash from judges and was eventually struck down by the Supreme Court on the ground that it undermined the judiciary’s independence. But independence, Dr Sengupta points out, should not mean “insulation”.

And although the judiciary has resisted government intervention in judicial appointments, critics argue it is hardly insulated from political influence. Lately, several decisions have seemingly favoured the government. In a recent interview, Prashant Bhushan, a Supreme Court lawyer and anti-corruption activist, claimed that “post-retirement jobs awarded to judges by the government” severely undermined judicial independence by creating perverse incentives for sitting judges.

Still, there are reasons to be optimistic. For all its faults, Indians are more confident in their courts than Americans, Britons and Japanese, according to Gallup, a pollster. And there is some evidence to suggest that, on the whole, the judiciary is fair. In a recent study, a team of economists from the Development Data Lab in Washington found no evidence that judges in India exhibit bias towards groups from their own communities, based on an analysis of more than 5m Indian criminal cases between 2010 and 2018.

Some courts have also shown they can improve their performance. Southern India dominates a national ranking of judicial performance put together by the India Justice Report. As in other domains, this superiority is thanks to better governance. Southern judiciaries use budgets more efficiently, invest more in court infrastructure and maintain better staff-to-case ratios than their northern counterparts.

They have also used technology, which perhaps offers the biggest opportunity for improving the judiciary. The High Court of Kerala, for example, has pioneered machine-learning examination of filings to speed up judges’ work and a case-management system that tightens schedules. If AI can help sort out this very human problem, then India stands to benefit. ■

China | Medical affairs

A sex scandal in China sparks a nationwide debate

The affair has morphed into a discussion about privilege and fairness

Photograph: Alamy

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

Though the trade war has been a hot topic of debate on Chinese social media over the past month, the Chinese public appears to have been just as exercised about an old-fashioned sex scandal at one of the country’s most elite hospitals. The scandal has morphed into a full-blown debate about privilege, ethics and (the lack of) fairness in Chinese society.

The story broke in mid-April and revolves around a senior surgeon called Xiao Fei at the China-Japan Friendship Hospital in Beijing. The first the public knew of Mr Xiao was when his estranged wife posted a letter online, alleging that he had been having affairs with work colleagues, including a junior doctor called Dong Xiying. The letter also accused Mr Xiao and Ms Dong of walking out of a surgical theatre where he was preparing for an operation, and leaving the anaesthetised patient unattended by a doctor for 40 minutes.

The hospital announced on April 27th that it had investigated the allegations and found they were “basically true”. It said Mr Xiao had been sacked and expelled from the Communist Party. (He told state media that he had not violated medical ethics, that he had left the patient for 10-20 minutes in the care of anaesthetists, and the reason for doing so was to defuse a dispute with a nurse.)

That was not enough to satisfy some members of the public, who suspected there was more to the story and had already started sniffing around. Top hospitals are redoubts of a health-care system that many citizens view as deeply unfair. Seeing specialists requires hours or even days of queuing. Treatment can be costly, often prohibitively so for the poor or migrants from the countryside. So if there was dirt, there were plenty of ordinary people willing to dig it up.

Back-door admissions

What they revealed was that Ms Dong had got her start in medicine on an experimental programme known as the “4+4” at Peking Union Medical College, one of the nation’s most prestigious. The scheme offers outstanding students with an undergraduate degree in another discipline an accelerated path to qualification as a doctor after four years, rather than the usual pathway which takes more than a decade. Ms Dong had studied economics at Barnard College in New York. Netizens asked why an American economics degree meant she needed only four years of medical school, and whether the 4+4 programme was simply a back door for the well-connected into a profession where people’s health and indeed lives were on the line.

In late April and early May the topic became one of the hottest online. On Weibo, a microblog platform, posts with the hashtag “Xiao Fei has been dismissed, when will Dong Xiying’s issues be investigated?” attracted more than 200m views. Some of China’s tabloid media joined the fray. “Frankly, this farce has evolved into an issue of social fairness,” Jimu News, an online service, posted to its Weibo account. It referred to reports that Ms Dong’s papers had suddenly disappeared from an academic database. “Could there be some hidden secrets that cannot see the light of day, prompting a hasty cover-up?”

Difficult operations

The scandal has put the authorities on the spot. Though they can sometimes suppress news completely, once a scandal gathers steam it can become more dangerous to try to squash it. So they try to manage it. State media have covered the main developments, but censors have struggled to keep online debate in check. It has veered into withering criticism of official corruption in hospitals and academia; of callous self-centredness among the well-connected; and, above all, of the way that plum jobs get taken by the high-born. As the economy falters and work becomes harder to find, the Communist Party is even less keen than usual to encourage discussion about such matters.

On May 15th the health ministry announced that Mr Xiao and Ms Dong had been stripped of their licences to work as physicians. The government will be hoping that those punishments—and the ministry’s promise to conduct a “comprehensive assessment” of the kind of fast-track scheme that Ms Dong joined—will put the whole affair to rest. By sacrificing the protagonists, it may be able to avoid making any further serious changes. Not surprisingly, the story has been pulled from Weibo’s list of “hot searches”.

Though the scandal has left a bitter taste, the public seems not to have lost its ability to laugh. One joke online has a patient admitting that he pulled strings to be treated at that particular hospital, whereupon the surgeon confesses that he, too, used contacts to get his job. The assistant surgeon admits the same. Finally the virus asks, “Am I the only one who got here on his own merits?” ■

United States | Lexington

Joe Biden did not decline alone

His party and the press lost altitude along with him

Illustration: David Simonds

May 19th 2025

Listen to this story

Accept, for a moment, Joe Biden’s contention that he is mentally as sharp as ever. Then try to explain some revelations of the books beginning to appear about his presidency: that he never held a formal meeting to discuss whether to run for a second term; that he never heard directly from his own pollsters about his dismal public standing, or anything else; that by 2024 most of his own cabinet secretaries had no contact with him; that, when he was in Washington, he would often eat dinner at 4.30pm and vanish into his private quarters by 5.15; that when he travelled, he often skipped briefings while keeping a morning appointment with a makeup artist to cover his wrinkles and liver spots. You might think that Mr Biden—that anyone—would welcome as a rationale that he had lost a step or two. It is a kinder explanation than the alternatives: vanity, hubris, incompetence.

In fact, by March 2023, there were times, behind the scenes, when Mr Biden seemed “completely out of it, spent, exhausted, almost gone”, according to “Original Sin”, by Jake Tapper, of CNN, and Alex Thompson, a reporter for Axios. In one encounter in December 2022, he did not remember the name of his national security adviser or communications director. “You know George,” an aide prodded Mr Biden in June 2024, coaxing him to recognise George Clooney, who was starring at a fundraiser for him.

Mr Biden’s aides tried to compensate by walking beside him to his helicopter, to disguise his gait and catch him if he stumbled, and by using two cameras for remarks to be shown on video so they could camouflage incoherence with jump cuts. Jonathan Allen, a reporter for NBC, and Amie Parnes, a reporter for the Hill, describe in “Fight” how aides would tack down fluorescent tape to guide the president to the lectern at fund-raisers. Once the most loquacious of politicians, Mr Biden ended up clinging to brief texts on teleprompters for even casual political remarks.

Such in-plain-sight accommodations point to what is slightly ridiculous about the present exercise of exposing Mr Biden’s decline. It was obvious to many people: to donors, to some Democratic politicians on the rare occasions they met him and, most important, to Americans, who saw through his pretence long before June 2024, when he fell apart in debate with Donald Trump. In April 2023, only a third of voters told Pew Research that they thought Mr Biden was “mentally sharp”.

For that reason, focusing on Mr Biden’s health is useful now less to tell a cautionary tale about his own decline, made even more melancholy by his cancer diagnosis, than one about the decline of his party and the press. “Fight” details how, after Mr Biden failed in debate, party leaders struggled to prevent the electoral catastrophe they foresaw. Even the most influential of Democrats, Barack Obama, who is portrayed as lacking confidence in both Mr Biden and Vice-President Kamala Harris, emerges in this account as ineffectual as he belatedly seeks some sort of “mini-primary”.

The parties have become so weak that whoever becomes their nominee can dominate them. Mr Biden’s vanity, and that of his family and closest aides, overrode common sense about whether he should seek a second term. Few Democrats spoke up about his infirmity while he was in office. With few exceptions, journalists from left-leaning news organisations, quick to deplore Mr Trump’s behaviour, competed to expose Mr Biden’s frailty only once Democrats were pushing him out. Journalists from right-leaning news organisations are still pounding away at Mr Biden’s mental or ethical lapses; they show less interest in Mr Trump’s.

“We got so screwed by Biden as a party,” David Plouffe, the rare Democrat in either book willing to attach his name to such criticism, told the authors of “Original Sin”. Mr Plouffe helped run Ms Harris’s campaign for president after she replaced Mr Biden. Mr Plouffe describes as “one of the great lessons from 2024” something that only a condescending, insular political organisation could possibly need to learn: “never again can we as a party suggest to people that what they’re seeing is not true”. (Regular readers may recall that Lexington, and The Economist, urged Mr Biden not to run again back when he was riding high, after the Democrats overperformed in the midterms of 2022.)

Many Democrats who condemn Republican congressmen for lacking the courage to oppose Mr Trump and call out his lies might instead pause to consider their own weakness, calculation or inattention. Even after that shocking debate, Democratic leaders who insisted Mr Biden was fit for a second term included not just Ms Harris but Governor Gavin Newsom of California, Governor J.B. Pritzker of Illinois and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, all possible presidential candidates. Have they since absorbed Mr Plouffe’s lesson?

A bridge, abridged

It’s the easy one. The party will probably not nominate an oldster again any time soon. Neither book shows that Mr Biden’s age led to policy failures by degrading his decision-making, as opposed to his communication skills (as essential as breath to a president). Regardless, nominating a young candidate won’t resolve the party’s confusion. The hard questions for Democrats are not about Mr Biden’s age but about how they should face the other challenges he struggled with, including immigration, the deficit and the implementation of his own infrastructure plan.

Revisionist historians may someday emphasise Mr Biden’s legislative achievements. But those cannot compensate for his hubris. Having once declared himself a bridge to a new generation, he became, instead, just a bridge “from one Trump term to the next”, the authors of “Fight” conclude. This may not be merely a story of the decline of a man, his party and the media. It may turn out to be about the decline of American democracy itself. ■

The Americas | Argentina economic reform

An election win boosts Javier Milei’s reform project

Lower inflation brings popularity. Popularity brings power, which helps with lowering inflation

Shouting in the cityPhotograph: AP

May 22nd 2025|MONTEVIDEO

Listen to this story

In most of the world mid-term elections for half of the seats in a city hall would be ignored by presidents and markets alike. Not so in Argentina. Javier Milei, the libertarian president, made his spokesperson his party’s leading candidate in elections held on May 18th in Buenos Aires. He cast the capital’s ballot as a referendum on his government. His party won 30% of the vote, compared with 27% for the leftist Peronists and 16% for the centre-right PRO, the party of a former president, Mauricio Macri. Argentine shares soared in response and sovereign bonds rose. Having beaten Mr Macri in his stronghold, Mr Milei intends to sideline him entirely, trying to subsume the PRO ahead of national mid-terms in October.

Argentine politics have been in flux since Mr Milei won the presidential race in late 2023 running as an angry outsider. He has slashed spending and brought raging inflation sharply down. In April he partially floated the peso. Yet Argentina has a history of woeful economic policy, and Mr Milei’s steps are not enough. A reformer also has to show repeatedly that he can keep the Peronists out. A struggling government and resurgent Peronists, even in minor elections, can spook markets and send the economy spiralling. This week’s win is a boost, though despite compulsory voting, turnout was at a historic low of 53%.

Two conclusions emerge. One is that politics will probably get angrier and dirtier. Mr Milei’s style is to rage against perceived enemies; the press is now a prime target. “People don’t hate journalists enough,” is his new catchphrase. Mr Milei also made his spokesperson the lead candidate while keeping him in post and giving him juicy announcements close to the election. More worrying was a fake video, generated using artificial intelligence, purporting to show Mr Macri urging people to vote for Mr Milei’s party in order to block the Peronists. It was shared on election eve by social-media accounts close to the president, including one widely reported to belong to his powerful spin doctor.

The second is that the government will continue to think that bringing inflation down is the path to electoral success—and will bet everything to that end. That is why after allowing the peso to float within a band, prompted in part by the IMF, the government has done all it can to keep the peso strong, avoiding a depreciation that would push inflation up. Interest rates remain high, while the government has tweaked rules to encourage foreigners to convert dollars into pesos in order to profit from a form of carry trade. A temporary tax break is pushing soyabean exporters to sell their harvest fast, also boosting the peso. The central bank has declared it will not buy dollars to rebuild its reserves until the peso touches its limit of 1,000 to the dollar, and has allegedly fiddled in the futures market to strengthen it. To the same end the government is expected to announce a loosening of rules on tax evasion, encouraging Argentines to bring an estimated $270bn hidden in mattresses back into the formal economy.

The approach is working, for now. Post-float depreciation was modest. Monthly inflation fell to 2.8% in April. Mr Milei may benefit from a flywheel effect whereby markets cheer his victory, which in turn boosts sovereign bonds and confidence in the peso, further staving off an inflationary depreciation. If inflation keeps falling he could win handsomely in October.

But flywheels can break down. The peso remains very strong, and so vulnerable to a depreciation, especially once the harvest ends in July. (Mr Milei surely hopes to delay any reckoning until after the mid-terms.) Boosting the peso makes exports less competitive. The central bank’s refusal to buy dollars to rebuild net reserves comes as it needs $5bn-odd by mid-June to meet the demands of the IMF’s new programme. It is preparing to borrow to do so, but that only delays the problem. The other risk is that the Peronists, who increased their seat share in Buenos Aires, do well in the mid-terms. That could spook people into dumping the peso, thus prompting inflation. For now such worries have not punctured Mr Milei’s euphoria. ■

Middle East & Africa | Gaza on the brink again

Israel says it is unleashing an “unprecedented attack”

More war beckons, as Donald Trump freezes out Binyamin Netanyahu

Photograph: Getty Images

May 19th 2025|JERUSALEM

Listen to this story

In a career of many crises Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, faces a defining moment. The path he chooses may alter Israel’s relationship with the Palestinians and America, its closest ally. One route involves reinvading Gaza to try to eradicate Hamas, which the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) are poised to do. That would cause more casualties, and further damage Mr Netanyahu’s relations with America and the Gulf states. The other path would involve a truce that could topple Mr Netanyahu’s government but repair Israel’s influence in the White House at a time when Mr Trump is reinventing American policy towards the Gulf, Syria and Iran. The implications of that shift could last decades.

The odds of the first path, reinvasion, are now dangerously high. On May 19th Mr Netanyahu said the IDF would be “taking control of all of Gaza”. His finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, a leader of one of the coalition’s far-right parties, went even further. “We are destroying what is still left of the strip, simply because everything there is one big city of terror,” he said.

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

The IDF has warned Gazans to leave Khan Younis, a key city, ahead of an “unprecedented attack”. Israel hopes a final surge will eradicate what remains of Hamas. On May 13th a strike may have killed Muhammad Sinwar, one of its last senior commanders. The humanitarian cost is likely to be staggering. Since the collapse of a ceasefire on March 18th, perhaps 5,000 Gazans have been killed, taking the total to over 50,000, including combatants. Hunger is widespread. In preparation for a ground attack the IDF has been conducting over 100 strikes a day.

The Trump administration appears to have granted Israel licence to act, but Mr Netanyahu himself appears not to have its support. Steve Witkoff, Mr Trump’s envoy, is said to have privately urged Mr Netanyahu to return to a deal. J.D. Vance, the American vice-president, was planning to go to Israel this week but has cancelled his visit, apparently because he did not want to appear to endorse Israel’s latest military expansion. Mr Trump and those close to him are refraining from openly criticising Israel’s government. The president has repeatedly said he would like to see the war end, for the hostages to be freed and for food to be let into Gaza. In public he has put the onus on Hamas. But the new distance between America and Israel may be widened still more if Israel reinvades Gaza.

Mr Netanyahu was blindsided by America’s decision to embark on talks with Iran on a nuclear deal. Likewise Mr Trump’s announcement that America had agreed to end its bombing campaign of the Houthis in Yemen, despite their continuing missile attacks on Israel, caught the prime minister unawares. Israel was conspicuously absent from the president’s itinerary during his Middle East tour. Saudi Arabia was meant to be the next Arab country to sign Mr Trump’s Abraham accords by normalising its ties with Israel, but Mr Trump has accepted that this will not happen until the war in Gaza is over. Mr Trump met Syria’s new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, and announced that he was lifting American sanctions on Syria, a step Israel had argued against. For Israel, having a free rein in Gaza seems to have come with a striking loss of influence.

Is the other path, a new truce, still possible? “Our operation in Gaza is staged so at any moment we can pull back if there’s a ceasefire,” says an Israeli general. Diplomacy may not be dead. American and Qatari diplomats are pressing Israel’s and Hamas’s teams in Doha to reach a new deal. Hamas has freed an American-Israeli soldier. Israel has allowed in a trickle of supplies to be distributed by aid groups, despite its claims they let Hamas steal them.

The probable death of Mr Sinwar may also help bring a ceasefire. With another hardliner out of the way, Hamas’s more pragmatic political leaders, who are based outside Gaza, may have more leeway. Still, the main obstacles to peace remain. Israel will countenance only a temporary truce, during which more of the hostages would be freed and more aid allowed in. But Hamas has ruled out any deal unless it permanently ends the war and is balking at Israel’s demand that it disarm and send its surviving Gazan leaders into exile.

Pressure is increasing on both sides. A majority of members of the European Union want the chance to re-examine Israel’s free-trade agreement with Europe, its main trading partner. Britain has suspended talks on a new trade deal. A majority of Israelis favour ending the war. Yair Golan, the leader of the opposition Democrats party, warned Israel could become a pariah state: “a sane country does not wage war against civilians, does not kill babies as a pastime, and does not engage in mass population displacement.” And Hamas is under pressure, too, as its people starve. In polls, around half of Gazans say they would leave given the chances.

Perhaps there will be a last-minute compromise. Without it, the future looks bleak. Mr Netanyahu says he will end the war only once he has won “total victory”. The total devastation of Gaza and isolation for Israel look more likely. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Europe’s mayors are islands of liberalism in a sea of populists

City bosses are the functioning bits of increasingly dysfunctional polities

Illustration: Peter Schrank

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

Every election in Europe these days seems to pit a moderate politician advocating mostly sensible ideas against a rabble-rousing populist with a bombastic dislike of migrants, gays and the European Union. The centrist usually wins, but the margins are dwindling. Is Europe thus destined to drift into reactionary dysfunction, one electoral setback at a time? Not so fast. Powerful as they may seem, Europe’s firebrand nationalists—even when they seize high office—are merely the meat in a liberal sandwich. Above them are EU wallahs, always on hand to police budget deficits and adhesion to the rule of law. Below the populists is a layer of pragmatic politicos who keep the day-to-day machinery of government on the road (and the roads free of potholes). Europe’s mayors, particularly those of big cities, are the unsung moderating force of the continent’s politics. Free of patriotic bombast and focused on getting buses running on time, they are the bulwark of moderate governance in a continent that needs it badly.

This quiet layer of mayoral technocracy has seen rapid promotions of late. On May 18th Nicusor Dan, the centrist mayor of Bucharest, unexpectedly trounced George Simion to win the presidency of Romania. The campaign highlighted their different approaches to government. The hard-right Mr Simion pontificated on foreign policy, boasted of being “almost perfectly aligned ideologically with the MAGA movement” and spent part of the final week of his campaign in Brussels, a place not actually in Romania. In contrast Mr Dan once admitted that what really kept him up at night was the traffic in the capital. Voters plumped for the traffic guy. Another centrist mayor may be propelled to higher office on June 1st when Rafal Trzaskowski, the centrist Warsaw mayor who narrowly won the first round last week, faces off against a candidate backed by the illiberal Law and Justice party.

At confabs in Brussels Mr Dan will meet fellow EU leaders familiar with cycle lanes, waste-water treatment and other unglamorous bits of the state. Bart De Wever, Belgium’s newish prime minister, was himself once perceived as a hard-right firebrand (his cause is the independence of Dutch-speaking Flanders), so much so that political rivals refused to include his party in ruling coalitions. A 12-year stint as mayor of Antwerp from 2013 was just the thing to show the electorate he was capable of more than soundbites. Giorgia Meloni once ran for mayor of Rome before settling for the Italian premiership; Ulf Kristersson, prime minister of Sweden, is an erstwhile vice-mayor of Stockholm. Meetings of EU leaders are chaired by António Costa, the president of the European Council who ran Lisbon for eight years before becoming Portugal’s prime minister.

Across Europe mayors are often cut from a different political cloth to the rest of the governing class. Lefties do notably well locally even when their parties are out of favour nationally—perhaps unsurprisingly, given the cosmopolitan types who choose to make cities their home. Parties of the hard right, which lack the organisational nous to put up candidates for dull city jobs, are notably absent. The municipal discourse thus has a gentler feel to it (at least until the building of cycle lanes is discussed). Amsterdam’s mayor, Femke Halsema, who is appointed by central government rather than elected, is a progressive woman in a Dutch political system dominated by progressive-bashing men. Socialists and their left-leaning allies have been routed in France, losing out on all the top jobs at national level—but they still run Paris, Marseille and most other big French cities. Ms Meloni and her right-wing acolytes dominate Italian politics, but the mayors of Rome and Milan come from the moribund left. (The same is true in America, where most big cities are run by Democrats.)

In central Europe, the spiritual home of continental illiberalism, local pols stand proudly as open-minded counterweights to majoritarian regimes. Fed up with the region being associated with the likes of Viktor Orban, the limelight-hogging Hungarian prime minister, the mayors of Prague, Bratislava, Warsaw and Budapest in 2019 set up a “Pact of Free Cities” where dynamic, hipsterish mayors showed another way was possible. The quartet travelled to Kyiv together to support Ukraine when some of their national leaders refused to do so. Another member of the club might have been Istanbul, whose mayor, Ekrem Imamoglu, proved such a threat to Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, that he was simply put in prison. The Pact now includes 32 European cities focused on “protecting democracy and open society”, not to mention sharing tips on handling thorny zoning issues.

From city council to European Council

Town halls are obvious places to find capable managers. Demagogues rise by making promises; mayors stay in power by keeping them. Not all politicians who have thrived as mayor do well on the national stage. Olaf Scholz will be remembered more fondly for his seven years as mayor of Hamburg than for his three as German chancellor. Anne Hidalgo, now in her second decade as mayor of Paris, managed a risible 1.8% of the vote in her bid for the French presidency in 2022, behind no fewer than nine other candidates.

Cities may seem easy to manage in comparison to countries. Often capitals are the richest part of the nation. Delivering public services is easier in densely populated places with a fat tax-base. But shortcomings are also easier to spot. Managerial ineptitude that exposes the shortcomings of populist national leaders can take years to emerge: underfunded public services degrade only slowly, and few voters follow the intricacies of foreign policy. In contrast, everyone swiftly notices when potholes go unfilled and buses run late. Blowhard politicians often talk about taking back control. Voters should pay more attention to those with a good record of taking care of the rubbish bins. ■

International | The Telegram

How to fight the next pandemic, without America

The world scrambles to save global health policy from Donald Trump

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

May 20th 2025

Listen to this story

HEARTFELT APPLAUSE greeted the adoption on May 20th of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, a treaty that commits governments to be more responsible and less selfish when future pandemics emerge. There was doubtless an edge of relief to the clapping. After three years of fierce argument, an overwhelming majority of health ministers and officials from over 130 countries—but not America, which is leaving the WHO and boycotting the treaty—voted to approve the text.

To cheerleaders, this was hopeful applause. The WHO boss, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, congratulated governments on a “victory for public health, science and multilateral action”. Opponents of the new pandemic agreement, who include the Trump administration but also populist politicians in Europe and elsewhere, might call those clapping sinister.

An executive order issued on President Donald Trump’s first day in office announced America’s withdrawal from the WHO and from negotiations to craft the new pandemic treaty. The order added that America would not be bound by amendments to international health regulations agreed on in 2024. Those changes, which tighten virus-surveillance and reporting obligations on governments, were demanded by American negotiators during the Biden administration. Mr Trump accuses the WHO of mismanaging the covid-19 pandemic under China’s influence, and of demanding too much money from America.

The pandemic treaty has sparked wild if vague claims in several countries. In 2024 a fringe candidate for America’s presidency called the pandemic agreement a power-grab by “international bureaucrats and their bosses at the billionaire boys’ club in Davos” that tramples Americans’ constitutional rights. Alas for the WHO, that long-shot candidate, Robert F. Kennedy junior, is now Mr Trump’s health secretary. In Britain, a right-wing political leader, Nigel Farage, falsely charges that the pandemic treaty will allow the WHO to impose lockdowns “over the heads of our elected national governments”. In fact, the treaty explicitly reaffirms the sovereign authority of national governments.

Was the applause in Geneva naive? Several times talks nearly collapsed, as bold promises made by world leaders during the covid-19 pandemic ran into long-standing divisions between high- and low-income countries. A year or two of hard wrangling still lies ahead, as governments hammer out the details of a political, scientific and commercial bargain at the heart of the treaty, known as the Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing system (PABS). That compact must balance the interests of very different places: on the one hand, the developing countries where many new viruses emerge; on the other, the wealthier nations where advanced vaccines and treatments are typically discovered.

Success is not a given. For PABS to save lives, some poor or struggling governments will need to step up surveillance of remote rural regions where people live among domestic and wild animals, and which create conditions that favour the spread of viruses into human hosts. They must report troubling discoveries swiftly and share pathogen samples with foreign scientists, even at the risk of suffering travel bans that bring trade and tourism to a halt. In return for free and rapid access to those same pathogens, some of the world’s most powerful governments and drug firms must commit to hand to the WHO, in real time, 20% of the vaccines, therapies and diagnostic tests they produce.

The politics of inequality nearly derailed the process. With reason, delegates from the global south accused rich countries of taking pathogens found among their populations, using them to create life-saving vaccines and drugs, then hoarding those same miracle cures for rich-world customers. Some developing countries called for cash payments for genetic data, following the model of an international agreement, the Nagoya Protocol, that allows countries to demand fees from drug and food companies or other entities that profit from their genetic heritage. Adopting PABS would make the sharing of pandemic-causing pathogens a public good, keeping Nagoya Protocol payments at bay.

Other emerging economies, notably those with fast-growing pharmaceutical industries, called for intellectual-property (IP) rights to be weakened or suspended during pandemics, and for technology transfers so that Africans and Asians can make their own vaccines. European governments said that defending IP was a red line, arguing that companies need to recoup research costs, or innovation will suffer. Rich-world pharmaceutical firms called the expansion of advanced vaccine-manufacture a noble but long-term goal. In the meantime, they argued, haggling with governments over fees for pathogens can slow down vital cures, for example, during a Zika-virus outbreak in Latin America in 2016.

Sometimes, avoiding failure is the big win

China was “very comfortable with the polarised debate” in Geneva, says an expert on the talks. “They had no interest in eroding IP protection, they have lots of IP. But they liked seeing a geopolitical fight between north and south.”

Mr Trump saved the treaty, argues Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global-health law at Georgetown University: governments compromised to save the multilateral order from America.

Aalisha Sahukhan heads the Centre for Disease Control on the Pacific island-state of Fiji and led her country’s delegation in Geneva. There is no guarantee that governments will keep treaty commitments, she concedes. Still, the mere act of agreeing on shared principles reassures small countries like hers. “A standard is set: this is how we should be behaving.” Much could still go wrong. But if nothing else, rational self-interest was tested and survived. That is surely worth a cheer. ■

Business | Bartleby

The secrets of public speaking

Lessons from actors on how to give a good presentation

Illustration: Paul Blow

May 19th 2025

Listen to this story

People who enjoy public speaking are luckier than they realise. A much-publicised survey from the 1970s claimed that Americans feared it more than death. In 2012 Karen Dwyer and Marlina Davidson of the University of Nebraska Omaha published a paper that tried to replicate the result. They found that things were less dramatic than that—but not by much.

Among the American students they surveyed, speaking in front of a group was indeed the most common fear, beating out financial problems, loneliness and death. When respondents were asked to rank their phobias, death pipped public speaking to the top spot. But this triumph for perspective ought not to be exaggerated. The grim reaper most scared one-fifth of students; but almost as many, 18%, picked having to stand up and talk in public as their principal fear. In sum, this staple office activity causes very many people to feel deeply anxious.

There is plenty of homespun advice out there for glossophobes. Just be yourself (which ignores the fact that the “real you” would rather be dead than give a presentation). Imagine that your audience is in their underwear (for reasons that are totally unclear). Speak on things you properly understand (when getting ahead in many jobs requires precisely the opposite).

A better source of advice comes from a profession that really knows how to pretend and perform: acting. Drama schools routinely offer communication coaching (if you like listening to journalists being humiliated, you can hear your columnist’s experience at RADA Business, an offshoot of the famous acting college in London, in the latest episode of our Boss Class podcast). “Don’t Say Um”, a recent book by Michael Chad Hoeppner, offers presenting tips from an actor-turned-coach.

The advice of professional performers can be condensed into three main messages. First, presenting is a deeply physical activity. Kate Walker Miles, one of the RADA Business coaches, warns against standing with legs locked straight; a slight bend in the knees makes for greater stability. She emphasises the importance of vowel sounds in communicating emotion, which means opening the jaw more widely than you might naturally tend to. Her warm-up exercises include some fairly ferocious massaging of the masseter muscles—think Edvard Munch and you get the idea—and some theatrical yawning. To achieve a relaxed posture, she asks clients to imagine being held up by a “golden thread” of infinite length which rises from the crown of their heads.

Second, it helps to slow down the pace of delivery—to allow for pauses, to not rush to fill silences with “ers”, “ums” and other verbal detritus. Mr Hoeppner recommends a useful technique called finger-walking, whereby you walk your index and middle fingers across the table as you speak, and only take a “step” when you know what the next word or point is going to be. Even doing it once is an interesting exercise: by forcing you to take time choosing your words, those filler noises start to disappear and language becomes more precise.

Third, don’t focus on yourself (or, in Ms Walker Miles’s phrase, turn “selfie view off”). Too often speakers concentrate on how they are doing—how many minutes to go? have I gone bright red?—and not on the experience of their audience. To help evoke the right emotion, actors have a technique called “actioning”, in which they assign a transitive verb (“pacify”, “bait”, “entice”, “repel”) to their lines in order to clarify a character’s goal. The emotional range of a quarterly update may not match “King Lear”, but executives should still work out what they want an audience to feel.

Some of these techniques can feel alien. Imagining that a golden thread is holding you up at the same time that you soften your knees, elongate your jaw and finger-walk your words is definitely something to try out at home first. But the value in them is also clear. Unusual professions often have less to teach managers than they claim (what does free diving have to teach you about budgeting? Answer: absolutely nothing). Acting really does have something to teach about how to communicate. ■

Business | Schumpeter

Big box v brands: the battle for consumers’ dollars

American retailers are slugging it out with their suppliers

Illustration: Brett Ryder

May 21st 2025

Listen to this story

DURING WALMART’S latest earnings call on May 15th, Doug McMillon stated the obvious. “The higher tariffs will result in higher prices,” the big-box behemoth’s chief executive told analysts, referring to Donald Trump’s levies on imports of just about anything from just about anywhere. Who’d have thought? Two days later the president weighed in with an alternative idea. Walmart (and China, where many of those imports come from) should “EAT THE TARIFFS”, he posted on social media. Mr McMillon did not respond publicly to the suggestion. But it is likely to be a polite, lower-case “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Walmart is not the only large American retailer that can afford to turn down the unhappy meal. Earlier this month Amazon hinted that prices of goods in its e-emporium could edge up as the levies bite. Costco, a lean membership-only bulk discounter which reports its quarterly earnings on May 29th, will probably not be taking up Mr Trump’s offer, either. This week Home Depot, America’s fourth-most-valuable retailer behind those three, said that while it was not planning to raise prices just yet, it expects to maintain its current operating margin. This implies its suppliers will absorb much of the cost of tariffs.

Not even the artificial-intelligence revolution seems to whet investors’ appetite as much as the ability to preserve profits in times of economic uncertainty. The giant retailers’ shares trade at multiples of future earnings that put big tech to shame. Home Depot’s is on a par with Meta’s. Walmart’s beats both Microsoft’s and Nvidia’s. Costco’s is nearly twice that of Apple. Amazon, with fingers in both pies, is just behind Walmart. Tasty.

Despite Walmart’s warning about everyday not-so-low prices, it is not shoppers who bear the brunt of its pricing power. It is, as in Home Depot’s case, suppliers. Retail firms can increasingly dictate terms not just to nameless providers of nuts-and-bolts products (including, at the home-improvement store, actual nuts and bolts) but also to once-mighty brands, from Nike to Nestlé. Do not be fooled by their single-digit operating margins, just over half those of their typical vendor. Their slice of the profits from the $5trn-plus that American consumers splurge annually on physical products is growing.

Estimating the retailers’ profit pool is straightforward. Start with the Census Bureau’s tally of American retail spending (excluding cars and petrol). This is, by definition, the money that ends up in shop tills. Multiply it by the industry’s overall operating margin, which can be approximated by looking at the revenue-weighted average of all listed retailers. Last year the figures were $5trn and 7.2%, giving $360bn in retail profits. Calculating vendors’ revenues requires a few more assumptions, such as that 90% of retailers’ cost of goods sold ends up with consumer-goods firms. This implies perhaps $3.2trn in sales and, given the average consumer-goods operating margin of 12.6% last year, a profit pool that is a shade over $400bn.

On this rough reckoning, then, manufacturers grab a little over half of the two groups’ combined profits. But this is down from three-fifths in the late 2010s. A narrower but more sophisticated analysis by Zhihan Ma of Bernstein, a broker, which focuses on food, hygiene and household products but excludes durable goods, yields a directionally similar result: over the past 15 years retailers’ profit share has risen from 34% to 38%. Having lagged behind consumer-goods stocks between 2000 and 2015, their shares have since handily outperformed them, too.

The main reason for retailers’ growing clout is competition. For established brands this is fiercer than ever. On one side they are squeezed by upstart labels, which can easily outsource production to contract manufacturers and market their wares on TikTok: think hip Warby Parker spectacles or hideous Allbirds trainers. When the economy looked healthy and money was cheap, brand owners could counteract some of this by snapping up the challengers. With interest rates, uncertainty and the risk of recession all up, dealmaking is the last thing on CEOs’ minds.

On the other side brands feel the pinch from retailers’ own private labels. These are no longer slapped just on low-margin goods like toilet paper. Best Buy, an electronics retailer, sells fancy own-brand refrigerators for $1,699. Wayfair flogs $7,800 sofas. Sam’s Club, Walmart’s Costco-like membership arm, even offers a five-carat diamond engagement ring for a bargain $144,999.

Even as shoppers enjoy ever more choice of what to buy, their options of where to buy it are becoming more limited. Although America’s retail industry remains fragmented compared with the cosy oligopolies found in many rich countries, it is consolidating fast. Between 1990 and 2020 the share of food sales claimed by the four biggest retailers more than doubled, to some 35%.

Food fight

A federal court’s decision last year to block the $25bn merger of Kroger and Albertsons, two big supermarkets, is scant comfort to vendors. They remain beholden to big retailers, especially Walmart, which accounts for a quarter of Americans’ grocery spending. Suppliers including Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever have set up offices next door to its headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. Walmart has no similar outposts in that trio’s hometowns of Vevey, Switzerland, Purchase, New York, and London.

During the last price shock, amid the covid-19 pandemic in 2021, consumer-goods firms could at least console themselves that stuck-at-home shoppers flush with stimulus cheques were willing to spend a bit more on branded goods. Their margins duly edged up that year. Now Mr Trump’s tariffs are about to hit just as consumer confidence is depressed. If they seek any retail therapy at all, it will be from Amazon, Costco and Walmart. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Hong Kong says goodbye to a capitalist crusader

David Webb was an exemplary shareholder

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

David Webb was quick to get his hands on the ZX Spectrum or “Speccy”, a computer launched in 1982 with up to 48 kilobytes of memory and rubber keys. Before he turned 18, he had written a book, “Supercharge Your Spectrum”, showing how to get the most out of the contraption with his favourite machine-code tricks and techniques. What set him apart from other tinkerers was how he spent the royalties. He would cycle to his bank in Oxford to place an order in London for some shares. (“Which stock, young man, do you want to buy?”)

That interest led naturally to a career in investment banking. His methodical mind mastered what you might call the machine code of capitalism: the rules, regulations and economic principles that make markets work, holding firms accountable to their customers and their owners. In 1991 he applied the same curiosity to Hong Kong, where he moved for a two-year stint that never ended. “I loved the place,” he says. By the time the Asian financial crisis rattled the city seven years later, Mr Webb had made enough money to retire. So in his early 30s he began trying to debug Hong Kong capitalism, sharing his favourite tricks and techniques via his website (webb-site.com) and a newsletter that now attracts over 30,000 subscribers.

At a farewell event hosted by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong on May 12th, Mr Webb, who is battling cancer, was philosophical about his achievements. Sometimes he changed things for the better; on other occasions he delayed a change for the worse. “That’s also a win,” he said.

Hong Kong was often celebrated as a bastion of economic liberty. But when Mr Webb began his crusades, its corporate governance was “lousy”, he says. Corporate reporting was slow and scanty. Shareholders had to wait four months for a two-page summary of a firm’s yearly results and another month for the annual report. At the same time, shareholder meetings were fast and perfunctory. Even important motions were often passed on a show of hands, no matter how many shares each “hand” represented. Big business dominated the legislature and the listing committee that sets rules for companies on the stockmarket.

In 2003 he exploited a “wrinkle” in the company law inherited from Britain, which allowed five shareholders to demand a formal poll on company resolutions. He bought ten shares in each of the companies in the Hang Seng index, Hong Kong’s main stockmarket benchmark, dividing them between himself, his wife and three firms he owned. With that foothold, he could oblige companies to conduct polls properly: one share, one vote. He also threatened to publish the results himself if they did not. His extra five shares allowed him to appoint proxies to appear at the meeting alongside him. He offered these five places to the press, which was otherwise barred from many meetings. “Tickets will be scarcer than the Rolling Stones,” he joked. Some journalists took up the invitation, mostly because they wanted to see what he, rather than the company, was up to.

Listed companies have to disclose “significant investments”, including shareholdings in other firms. At Mr Webb’s urging, the regulator began to enforce the rule. That let him map out a web of holdings among 50 firms he dubbed the Enigma Network. A company might borrow from another on advantageous terms with no intention to repay, or dilute the stakes of independent investors by issuing lots of shares, snapped up at a discount by insiders if minority shareholders did not fork out for them. An umbrella-maker issued 75bn shares (“in case everyone on Earth wants ten”, as Mr Webb put it). In 2017, six weeks after he published his map, the shares of many Enigma firms crashed.

He also fought a rear-guard action against weighted voting rights, which allow firms to issue special shares that carry more clout. He feared this would further entrench tycoons, allowing their control to exceed their ownership stake. But Hong Kong’s exchange was keen to attract Chinese tech companies led by celebrity founders, which are often popular even with minority investors.

Not all sharebuyers take much interest in capitalism’s inner workings. Many simply want exposure to a stock’s returns, even without the other rights of ownership. They are happy to free-ride on the efforts of more careful stewards of capital, such as Mr Webb. Capitalism in Hong Kong works better thanks to him. And it would work better still if more capitalists were like him. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

America’s scientific prowess is a huge global subsidy

And it is now under threat

Illustration: Álvaro Bernis

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

One of the best things about living in Europe is America. Faced with a moribund domestic stockmarket, European investors can redirect their savings into the s&p 500. Residents enjoy the protection of America’s security umbrella without having to foot the bill. At times of crisis the continent’s central banks rely on swap lines from the Federal Reserve. All the while they enjoy better food, nicer cities and superior cultural offerings.

But America, under President Donald Trump, now threatens to withdraw many of these implicit subsidies. His administration’s attacks on science, involving deep cuts to the budgets of institutions, may damage the biggest subsidy of all. America is a research powerhouse. It has the best universities. It accounts for 4% of the world’s population, yet produces a third of high-impact scientific papers. It also accounts for a third of global research-and-development spending.

Americans benefit most of all from their country’s scientific prowess. The average American medical scientist earns $100,000 a year, for instance—some 60% more than the average American worker. But as any economist knows, knowledge is a public good, meaning science has large “spillover” benefits. In 2004 William Nordhaus of Yale University argued that companies only capture 2.2% of the total returns from their innovations. Patents expire and even before that competitors copy ideas. Innovation therefore drags up everyone’s living standards, as lots of companies become more productive and ordinary people benefit from better goods and services. America’s average incomes are fantastically high.

Economists have devoted less attention to the question of international spillovers. Nevertheless, America almost certainly runs a surplus in science with the rest of the world, providing much more to foreigners than it receives in return. In recent years, too, the size of this subsidy has almost certainly grown. Three mechanisms stick out—all of which are now under threat.

First, people. American scientific institutions are a melting pot. There are twice as many foreign students today as in the early 2000s. Many outsiders, having graduated, return home, taking ideas with them. We estimate that around 15% of the people who have graduated from mit, a top American science school, live abroad. On that basis, the raw material of future scientific progress has already spilled out from America to elsewhere.

Second, new ideas. When a scientist publishes a paper online, almost anyone in the world can read it. Traditionally research was a domestic affair. One bibliometric study found that in 1996 only about 40% of citations of American scientific publications were from foreign researchers. More recently the globalisation of scientific knowledge has intensified. By 2019 foreign scientists accounted for about 60% of America’s citations. Scientists in the rest of the world thus stand on the shoulders of American giants.

American consumers also subsidise r&d. This is most well-known in the case of pharmaceuticals. Prescription drugs are more expensive domestically than abroad. American consumers, in effect, pay for the research that creates them. And this pattern is apparent elsewhere, too. National-accounts data suggest that, on average, American corporations earn returns on domestic capital that are more than 50% higher than abroad. So while Americans may fund corporate r&d, the world shares the benefit.

The third factor is new technologies. Every other country has long drawn from the well of American innovations. This was how Europe rebuilt itself following the second world war. French steel executives visited American steelworks in order to copy workflow designs. Britain’s car bosses turned to American executives in an attempt to improve plant efficiency. Economists struggle to measure the ways in which American tech spills abroad today. In some cases the American government explicitly provides it to the world for free, as in the case of gps. During the covid-19 pandemic America gave away vaccines to poor countries. Many American artificial-intelligence companies release “open source” models. Even when American firms try to protect their intellectual property, foreign competitors find workarounds. Many other smartphone companies have copied Apple’s aesthetic, for instance.

According to Nancy Stokey of the University of Chicago, one quantitative measure of technological spillovers involves looking at capital goods, in which new tech is often embodied. From the early 1990s to 2024 America exported nearly $5trn-worth of high-tech capital goods, more than any other country, spreading the American way to every corner of the Earth. Another proxy is outward foreign direct investment. This is when an American buys a controlling stake in a foreign business or builds a new industrial facility abroad—and often introduces new tech as part of the bargain. Americans’ direct investments abroad are worth some $10trn, which is far more than any other country.

Nutty professor

If Mr Trump follows through with his proposed cuts, and America’s scientific system stumbles, can another country pick up the mantle? Many American scientists say they want to leave the country; a few already have. China, which on some measures of scientific prowess already surpasses America, may hope to capitalise. Yet few foreigners want to do their phd in China. A closed political system slows down the diffusion of innovations across international borders. So does the language barrier.

Even if China changed, however, decades of research on economic clusters shows that they are rarely replicated. Just as you could not uproot Hollywood and move it elsewhere, scientists leaving Berkeley and Boston will not carry on as before when they arrive in Beijing or, indeed, London. If America’s scientific system sneezes, the rest of the world will catch a cold. ■

Finance & economics | American titan

Will Jamie Dimon build the first trillion-dollar bank?

We interview JPMorgan Chase’s boss, and his lieutenants

Photograph: Benedict Evans for The Economist

May 22nd 2025|New York

Listen to this story

“Serena Williams, Tom Brady, Stephen Curry.” When it comes to making sure the world’s biggest bank is a lean operation, Jamie Dimon takes athletic inspiration. “Look how they train, what they do to be that good,” says the boss of JPMorgan Chase. “Very often, senior leadership teams, they lose that. Companies become very inward-looking, dominated by staff, which is a form of bureaucracy.”

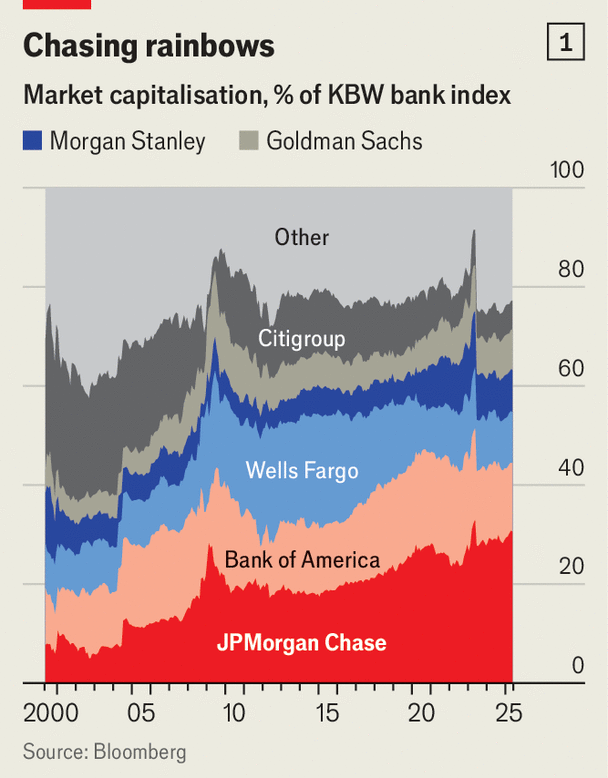

During Mr Dimon’s tenure, JPMorgan has become to banking what Ms Williams was to tennis. In most of the markets in which it competes, it ranks as America’s leading institution, or a close runner-up. It boasts a market capitalisation of $730bn, or 30% of the total among America’s big banks, up from 12% when Mr Dimon took charge at the start of 2006 (see chart 1). The gap with competitors has grown larger still since the covid-19 pandemic. JPMorgan has 317,233 staff, nearly twice as many as in 2005. Its share of American deposits has doubled to 12%.

Chart: The Economist

America has never had a bank of such size. Even when John Pierpont Morgan, one of Mr Dimon’s predecessors, bailed out the Treasury at the turn of the 20th century, he could not boast coast-to-coast operations. In 2021 JPMorgan became the first lender with branches in every one of America’s 48 contiguous states. The bank’s combination of scale and market-beating efficiency means that it can invest far more than its rivals in technology, draw on an immense hoard of deposits for cheap and sticky funding, and benefit from flights to safety when smaller banks wobble.

But the institution’s tremendous size, success and prominence pose risks, too. Banking is not a business that suffers mistakes gladly; the larger and more unwieldy an institution, the longer the list of potential slip-ups. Being the biggest bank in a country where small lenders are sacred makes JPMorgan an obvious political target, from both the left and right. And then there is the succession question. How do you replace a man of Mr Dimon’s reputation? And how does someone without his stature prevent infighting and bureaucracy at an institution of JPMorgan’s size?

Photograph: Benedict Evans for The Economist

Mr Dimon sat down for an interview with The Economist on May 16th. We also met the four bosses of the bank’s biggest businesses—the most likely candidates to succeed Mr Dimon—beforehand. They are Troy Rohrbaugh, co-head of the commercial and investment bank; Douglas Petno, its other boss; Mary Erdoes, who runs the wealth-management arm; and Marianne Lake, leader of retail operations. Each is a loyal lieutenant and JPMorgan veteran. Mr Rohrbaugh is the most recent hire; he has worked at JPMorgan for 20 years.

On January 1st next year, Mr Dimon will have been at the helm of the bank for the same amount of time. On March 13th he will celebrate his 70th birthday. His succession has been a subject of relentless discussion on Wall Street for over a decade, spurred on by two health scares and the prospect that he might be made treasury secretary. Mr Dimon says that in the next few years he will step down but remain the company’s chairman, and stubbornly refuses to provide a firmer timeline. He does offer some traits for any future leader of the bank: “There’s a work ethic; there’s people skills. There’s determination. You better have a little bit of grit. There’s humility; there’s ability to form teams. There’s having courage. Constantly observing the world out there and thinking, ‘Well, what can be done better?’”

Chart: The Economist

Well, what could be? Not much, if you listen to Mike Mayo of Wells Fargo, the most prominent JPMorgan analyst and an uber-bull. Indeed, Mr Mayo has asked why Jamie Dimon would want to step down at all. The bank is, he says, the “Goliath of Goliaths” and the best he has covered in his career; he expects it to be the first with a trillion-dollar valuation. Part of his argument is that advances in artificial intelligence mean investment in tech has grown in importance, and JPMorgan, which he also calls the “Nvidia of banking”, can afford more than any rival. The bank will spend about $18bn on tech this year, some 40% more than Bank of America.

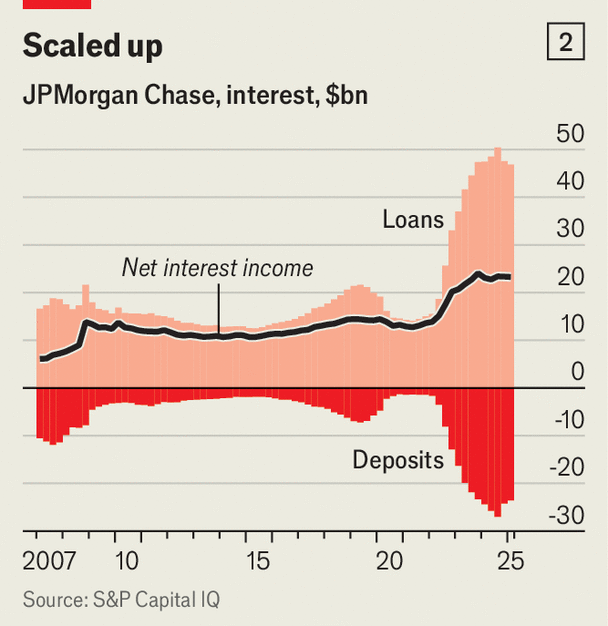

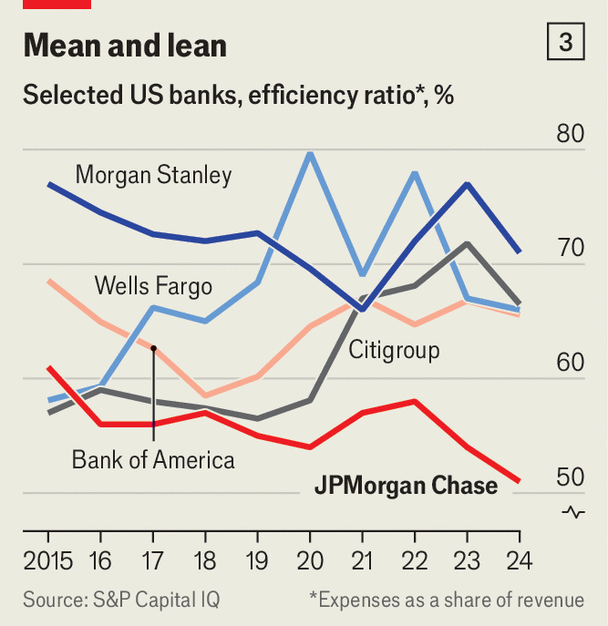

The heft that JPMorgan has developed under Mr Dimon provides the bank with a compounding advantage. Wall Street executives moan about how hard it is to compete across JPMorgan’s full range of businesses. The bank has an enormous base of $2.5trn in deposits. Over the past two years it has paid out $190bn in interest on deposits, while hoovering up $374bn in interest on loans (see chart 2). Yet the bank is not just larger than its rivals—it is also more streamlined. Its efficiency ratio (non-interest expenses as a share of total revenue) has dropped from 61% in 2015 to 51%, a figure that is 15 percentage points lower than any competitor (see chart 3).

Chart: The Economist

Increasingly, JPMorgan’s competition is to be found outside banking. “I want us to be better than the best in class, which is in many ways the non-bank trading houses,” says Mr Rohrbaugh. “In other parts of our business, like in payments, we’re not only competing against the big banks, we’re competing against fintechs.” Vast trading firms such as Citadel Securities and Jane Street have seized market-making activities once dominated by banks, while techy upstarts such as Stripe eat into payments.

According to clients, JPMorgan has stayed efficient because its businesses have remained complementary. It has avoided both becoming a conglomerate made up of unrelated silos and falling into zero-sum internal competition. “You have to sew all those pieces together,” says Ms Erdoes, who has run wealth management since 2009, meaning she has been in her current job the longest of the four bosses. “That’s really easy at our operating-committee level, because we live with each other. It’s harder when you’ve got the person in the Milan office who’s trying to find the person in the Austin, Texas office.”

Mr Dimon’s “fortress” balance-sheet helps. Large reserves, low leverage and plentiful capital serve JPMorgan well in times of stress, allowing it to snap up firms. The bank bought Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, a pair of banks, as the financial crisis worsened in 2008. Two years ago, during a smaller crisis, it acquired the lion’s share of assets from First Republic, America’s 14th-largest bank. “We did it because the government needed it,” says Mr Dimon. But “we have to make it financially attractive to ourselves, obviously.”

Manning the fort

The stress in 2023 had lessons for JPMorgan. “When Silicon Valley Bank failed, we learned a lot about what we didn’t do properly covering Silicon Valley,” says Mr Dimon. “Even though we’re out there all the time and we did a lot of stuff. The [lesson of the] deep-dive was that we didn’t have a consistent, devoted calling on venture capitalists.” That year JPMorgan hired John China, former president of SVB Capital, Silicon Valley Bank’s venture-capital arm, to jointly run its “innovation economy” business. His job is to tie America’s financial capital to its tech capital.

At the same time as other firms are cutting back in San Francisco, or abandoning the city altogether, JPMorgan last month announced plans to increase the size of its offices in the city by 30%. “When you bank the venture capitalist, you bank them individually, you bank their firm, you bank their startups and you bank their founders,” notes Mr Petno. The exercise-obsessed, joke-cracking Mr Petno is a veteran even among the veterans, having worked at JPMorgan for 35 years. The firm’s analysts think that his promotion, in January, to jointly run the investment bank puts him in serious contention for the top job.

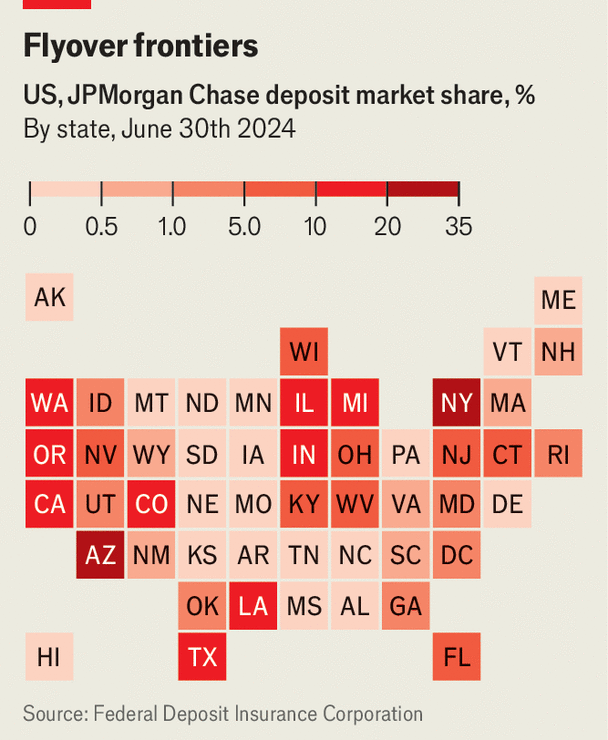

Map: The Economist

Meanwhile, the bank’s retail operations are spreading across the country. Ms Lake, their boss, who grew up in Britain and speaks with a crisp English accent, wants a 15% share of American deposits, a cautious goal. Over the past six years, JPMorgan has established a physical presence in 25 states. It takes several years for branches to reach their potential, and in dozens of cities—Boston, Salt Lake City and Washington included—the bank still oversees less than 3% of deposits. JPMorgan is growing overseas, too. Almost four years after launching a digital consumer bank in Britain, it has 2m customers. Germany is next. “We have previously said Europe is more difficult, but that is different today with digital banking,” explains Ms Lake.

Could anything halt JPMorgan’s ascent? Scale is no guarantee of success. At the turn of the century, another institution accounted for 30% or so of the market capitalisation of American banks. After a barrage of mergers and acquisitions, Citigroup was a titan. But its lead was eroded by a series of scandals in the 2000s, and a bad financial crisis. Today it accounts for less than 6% of the industry’s market capitalisation. By comparison, JPMorgan has been pretty scandal-free under Mr Dimon—with the exception of the “London Whale” farrago, when a rogue trader cost the institution over $6bn.

JPMorgan’s size also makes it a target. In normal circumstances, American law would not allow it to merge with another lender, owing to its market share. But the rule does not apply if the lender is failing, which is what allowed it to buy First Republic. All the same, JPMorgan was criticised. Elizabeth Warren, a left-wing senator, paired up with J.D. Vance, now vice-president, to attack the sale. It made “the nation’s largest bank grow even bigger”.

Photograph: Benedict Evans for The Economist

Mr Dimon is unrepentant, arguing large banks offer America vital heft. “We move $10trn a day...We have lent $35bn to a company to get a deal done. You know, we bank the biggest companies around, we bank countries,” he says. “I don’t think necessarily the people making those statements understand why you need a big bank that does business in 100 countries and that market-makes like we do.”