The Economist Articles for June. 2nd week : June. 8th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.05.30조회수113 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for June. 2nd week : June. 8th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | New and untested

American finance, always unique, is now uniquely dangerous

Donald Trump is putting an untested system under almighty strain

May 29th 2025

Listen to this story

ALWAYS A HAVEN in dangerous times, America has itself become a source of instability. The list of anxieties is long. Government debt is rising at an alarming pace. Trade policy is beset by legal conflicts and uncertainties. Donald Trump is attacking the country’s institutions. Foreign investors are skittish and the dollar has tumbled. Yet, astonishingly, one big danger lurks unnoticed still.

When you think of financial risk, you may picture investment-banking capers on Wall Street or subprime mortgages in Miami. But, as our special report explains, over the past decade American finance has been transformed. A mix of asset managers, hedge funds, private-equity firms and trading firms—including Apollo, BlackRock, Blackstone, Citadel, Jane Street, KKR and Millennium—have emerged from the shadows to elbow aside the incumbents. They are fundamentally different from the banks, insurers and old-style funds they have replaced. They are also big, complex and untested.

The financial revolution is now encountering the MAGA revolution. Mr Trump is hastening the next financial crisis by playing havoc with trade, upending America’s global commitments and, most of all, by prolonging the government’s borrowing binge. America’s financial system has long been dominant, but the world has never been as exposed to it. Everyone should worry about its fragility.

Special report: A new financial order

The new firms are a magnet for financial talent. They also enjoy regulatory advantages, because governments forced banks to hold more capital and rein in their traders after the financial crisis of 2007-09. That combination has led to a spate of innovation, supercharging the firms’ growth and propelling them into every corner of finance.

Three big private-markets firms, Apollo, Blackstone and KKR, have amassed $2.6trn in assets, almost five times as much as a decade ago. In that time the assets of large banks grew by just 50% to $14trn. In the search for stable funding, the upstarts have turned to insurance; Apollo, which made its name in private equity and merged with its insurance arm in 2022, now issues more annuities than any other American insurer. The firms lend to households and blue-chip companies such as Intel. Apollo alone lent $200bn last year. Loans held by large banks increased by just $120bn. New-look trading firms dominate stockpicking and marketmaking. In 2024 Jane Street earned as much trading revenue as Morgan Stanley.

There is much to like about this new financial system. It has been highly profitable. In some ways, it is also safer. Banks are vulnerable to runs because depositors fear being the last in the queue to withdraw their money. All things being equal, finance is more stable when loans are financed by money that is locked up for longer periods.

Most importantly, the dynamism of American finance has channelled capital towards productive uses and world-beating ideas, fuelling its economic and technological outperformance. The artificial-intelligence boom is propelled by venture capital and a new market for data-centre-backed securities. Bank-based financial systems in Europe and Asia cannot match America’s ability to mobilise capital. That has not only set back those regions’ industries, it has also drawn money into America. Over the past decade, the stock of American securities owned by foreigners doubled, to $30trn.

Unfortunately, the new finance also contains risks. And they are poorly understood. Indeed, because they are novel and untested by a crisis, they have never been quantified.

One lot of worries come from within the system. The new giants are still bank-like in surprising ways. Although it is costly to redeem a life-insurance policy early, a run is still possible should policy holders and other lenders fear that the alternative is to get back nothing. And although the banks are safer, depositors are still exposed to the new firms’ risk-taking. Bank loans to non-bank financial outfits have doubled since 2020, to $1.3trn. Likewise, the leverage supplied to hedge funds by banks has ballooned from $1.4trn in 2020 to $2.4trn today.

The new system is also dauntingly opaque. Whereas listed assets are priced almost in real time, private assets are highly illiquid. Mispriced risks can be masked until assets are suddenly revalued, forcing end investors to scramble to cover their losses. Novel financial techniques have repeatedly blown up in the past because financial innovators are driven to test their inventions to breaking-point and, the first time round, that threshold is unknown.

Under Mr Trump, the next upheaval is never far away. The government’s excessive borrowing imperils bond markets, alarming foreign investors. Although a court has this week limited the president’s powers to wage trade wars, the administration is appealing and Mr Trump is unlikely to abandon tariffs altogether. A toxic combination of uncertainty, institutional conflict, volatile asset prices, higher capital costs and economic weakness threatens to put the new-look financial system under almighty strain.

A crisis would test even the most capable policymaker. Much about the risks of the superstar firms, and their linkages to the wider financial system and the real economy, will become clear only when trouble strikes. New emergency-lending schemes would be needed. Rescuing banks last time was politically toxic. Saving billionaire investors would be an altogether harder task. And yet if the biggest of these giant firms were left to fail, it could lead to a global credit crunch.

Under Mr Trump a rescue would be unpredictable. In 2008 the Treasury and the Federal Reserve acted quickly to save the banks, and set up swap lines to offer dollar funding to much of the world. Mr Trump might decide to bail out everyone. But imagine the panic if he started to pick his favourite financiers, threatened to abandon or charge countries that displeased him and changed his mind every five minutes on Truth Social.

There will be another financial crisis—there always is. Nobody knows when disaster will strike. But when it does, investors will suddenly wake up to the fact that they are dealing with a financial system they do not recognise. ■

Leaders | Vietnam

The man with a plan for Vietnam

A Communist Party hard man has to rescue Asia’s great success story

May 22nd 2025

Listen to this story

Fifty years ago the last Americans were evacuated from Saigon, leaving behind a war-ravaged and impoverished country. Today Saigon, renamed Ho Chi Minh City, is a metropolis of over 9m people full of skyscrapers and flashy brands. You might think this is the moment to celebrate Vietnam’s triumph: its elimination of severe poverty; its ranking as one of the ten top exporters to America; its role as a manufacturing hub for firms like Apple and Samsung. In fact Vietnam has trouble in store. To avoid it—and show whether emerging economies can still join the developed world—Vietnam will need to pull off a second miracle. It must find new ways to get rich despite the trade war, and the hard man in charge must turn himself into a reformer.

That man, To Lam, isn’t exactly Margaret Thatcher. He emerged to become the Communist Party boss from the security state last year after a power struggle. He nonetheless recognises that his country’s formula is about to stop working. It was concocted in the 1980s in the doi moi reforms that opened up the economy to trade and private firms. These changes, plus cheap labour and political stability, turned Vietnam into an alternative to China. The country has attracted $230bn of multinational investment and become an electronics-assembly titan. Chinese, Japanese, South Korean and Western firms all operate factories there. In the past decade Vietnam has grown at a compound annual rate of 6%, faster than India and China.

The immediate problem is the trade war. Vietnam is so good at exporting that it now has the fifth-biggest trade surplus with America. President Donald Trump’s threat of a 46% levy may be negotiated down: Vietnam craftily offered the administration a grab-bag of goodies to please the president and his allies, including a deal for SpaceX and the purchase of Boeing aircraft. On May 21st Eric Trump, the president’s son, broke ground at a Trump resort in Vietnam which he said would “blow everyone away”.

But even a reduced tariff rate would be a nightmare for Vietnam. It has already lost competitiveness as factory wages have risen above those in India, Indonesia and Thailand. And if, as the price of a deal, America presses Vietnam to purge its economy of Chinese inputs, technology and capital, that will upset the delicate geopolitical balancing act it has performed so well. Like many Asian countries it wants to hedge between an unreliable America and a bullying China which, despite being a fellow communist state, has long been a rival and now disputes Vietnam’s claim to coastal waters and atolls. The trade and geopolitical crunch is happening as the population is ageing and amid rising environmental harm, from thinning topsoils in the Mekong Delta to coal-choked air.

Mr Lam made his name orchestrating a corruption purge called “the blazing furnace”. Now he has to torch Vietnam’s old economic model. He has set expectations sky-high by declaring an “era of national rise” and targeting double-digit growth by 2030. He has made flashy announcements, too, including quadrupling the science-and-technology budget and setting a target to earn $100bn a year from semiconductors by 2050. But to avoid stagnation, Mr Lam needs to go further, confronting entrenched problems that other developing countries also face as the strategy of exporting-to-get-rich becomes trickier.

Vietnam’s growth miracle is concentrated around a few islands of modernity. Big multinational companies run giant factories for export that employ locals. But they mostly buy their inputs abroad and create few spillovers for the rest of the economy. This is why Vietnam has failed to increase the share of the value in its exports that is added inside the country. A handful of politically connected conglomerates dominate property and banking, among other industries. None is yet globally competitive, including Vietnam’s loss-making Tesla-wannabe, VinFast, which is part of the biggest conglomerate, Vingroup. Meanwhile, clumsy state-owned enterprises still run industries from energy to telecoms.

To spread prosperity, Mr Lam needs to level the playing field for smaller firms and new entrants. That means hacking back a bewildering licensing regime and allowing credit to flow to small firms by shaking up a corruption-prone banking industry. Legislation issued this month abolishes a tax on household firms and strengthens legal protection for entrepreneurs. That is a step in the right direction, but Mr Lam also needs to free up universities so that ideas flow more easily and innovations thrive.

This is where it gets risky. Vietnam’s people would without a doubt benefit from a more liberal political system. But although that may also help development, China has shown that it may not be essential—at least not immediately. What is crucial is facing down powerful vested interests that hog scarce resources. A good start would be forcing the oligarchs to compete internationally or lose state support, as South Korea did with its chaebols. Often they are protected by cronies and pals within the state apparatus and the Communist Party. Encouragingly, Mr Lam has already begun a high-stakes streamlining of the state, including by laying off 100,000 civil servants. He is also halving the number of provinces in a country where regions have sponsored powerful factions within the party. And he is abolishing several ministries. All this will modernise the bureaucracy, but it is also a brilliant way of making enemies.

The autocrat’s dilemma

The danger is that, like Xi Jinping in China, Mr Lam centralises power so as to renew the system—but in the process perpetuates a culture of fear and deference that undermines his reforms. If Mr Lam fails, Vietnam will muddle on as a low-value-added production centre that missed its moment. But if he succeeds, a second doi moi would propel 100m Vietnamese into the developed world, creating another Asian growth engine and making it less likely that Vietnam will fall into a Chinese sphere of influence. This is Vietnam’s last best chance to become rich before it gets old. Its destiny rests with Mr Lam, Asia’s least likely, but most consequential, reformer. ■

Business | Schumpeter

Big box v brands: the battle for consumers’ dollars

American retailers are slugging it out with their suppliers

Illustration: Brett Ryder

May 21st 2025

Listen to this story

DURING WALMART’S latest earnings call on May 15th, Doug McMillon stated the obvious. “The higher tariffs will result in higher prices,” the big-box behemoth’s chief executive told analysts, referring to Donald Trump’s levies on imports of just about anything from just about anywhere. Who’d have thought? Two days later the president weighed in with an alternative idea. Walmart (and China, where many of those imports come from) should “EAT THE TARIFFS”, he posted on social media. Mr McMillon did not respond publicly to the suggestion. But it is likely to be a polite, lower-case “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Walmart is not the only large American retailer that can afford to turn down the unhappy meal. Earlier this month Amazon hinted that prices of goods in its e-emporium could edge up as the levies bite. Costco, a lean membership-only bulk discounter which reports its quarterly earnings on May 29th, will probably not be taking up Mr Trump’s offer, either. This week Home Depot, America’s fourth-most-valuable retailer behind those three, said that while it was not planning to raise prices just yet, it expects to maintain its current operating margin. This implies its suppliers will absorb much of the cost of tariffs.

Not even the artificial-intelligence revolution seems to whet investors’ appetite as much as the ability to preserve profits in times of economic uncertainty. The giant retailers’ shares trade at multiples of future earnings that put big tech to shame. Home Depot’s is on a par with Meta’s. Walmart’s beats both Microsoft’s and Nvidia’s. Costco’s is nearly twice that of Apple. Amazon, with fingers in both pies, is just behind Walmart. Tasty.

Despite Walmart’s warning about everyday not-so-low prices, it is not shoppers who bear the brunt of its pricing power. It is, as in Home Depot’s case, suppliers. Retail firms can increasingly dictate terms not just to nameless providers of nuts-and-bolts products (including, at the home-improvement store, actual nuts and bolts) but also to once-mighty brands, from Nike to Nestlé. Do not be fooled by their single-digit operating margins, just over half those of their typical vendor. Their slice of the profits from the $5trn-plus that American consumers splurge annually on physical products is growing.

Estimating the retailers’ profit pool is straightforward. Start with the Census Bureau’s tally of American retail spending (excluding cars and petrol). This is, by definition, the money that ends up in shop tills. Multiply it by the industry’s overall operating margin, which can be approximated by looking at the revenue-weighted average of all listed retailers. Last year the figures were $5trn and 7.2%, giving $360bn in retail profits. Calculating vendors’ revenues requires a few more assumptions, such as that 90% of retailers’ cost of goods sold ends up with consumer-goods firms. This implies perhaps $3.2trn in sales and, given the average consumer-goods operating margin of 12.6% last year, a profit pool that is a shade over $400bn.

On this rough reckoning, then, manufacturers grab a little over half of the two groups’ combined profits. But this is down from three-fifths in the late 2010s. A narrower but more sophisticated analysis by Zhihan Ma of Bernstein, a broker, which focuses on food, hygiene and household products but excludes durable goods, yields a directionally similar result: over the past 15 years retailers’ profit share has risen from 34% to 38%. Having lagged behind consumer-goods stocks between 2000 and 2015, their shares have since handily outperformed them, too.

The main reason for retailers’ growing clout is competition. For established brands this is fiercer than ever. On one side they are squeezed by upstart labels, which can easily outsource production to contract manufacturers and market their wares on TikTok: think hip Warby Parker spectacles or hideous Allbirds trainers. When the economy looked healthy and money was cheap, brand owners could counteract some of this by snapping up the challengers. With interest rates, uncertainty and the risk of recession all up, dealmaking is the last thing on CEOs’ minds.

On the other side brands feel the pinch from retailers’ own private labels. These are no longer slapped just on low-margin goods like toilet paper. Best Buy, an electronics retailer, sells fancy own-brand refrigerators for $1,699. Wayfair flogs $7,800 sofas. Sam’s Club, Walmart’s Costco-like membership arm, even offers a five-carat diamond engagement ring for a bargain $144,999.

Even as shoppers enjoy ever more choice of what to buy, their options of where to buy it are becoming more limited. Although America’s retail industry remains fragmented compared with the cosy oligopolies found in many rich countries, it is consolidating fast. Between 1990 and 2020 the share of food sales claimed by the four biggest retailers more than doubled, to some 35%.

Food fight

A federal court’s decision last year to block the $25bn merger of Kroger and Albertsons, two big supermarkets, is scant comfort to vendors. They remain beholden to big retailers, especially Walmart, which accounts for a quarter of Americans’ grocery spending. Suppliers including Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever have set up offices next door to its headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. Walmart has no similar outposts in that trio’s hometowns of Vevey, Switzerland, Purchase, New York, and London.

During the last price shock, amid the covid-19 pandemic in 2021, consumer-goods firms could at least console themselves that stuck-at-home shoppers flush with stimulus cheques were willing to spend a bit more on branded goods. Their margins duly edged up that year. Now Mr Trump’s tariffs are about to hit just as consumer confidence is depressed. If they seek any retail therapy at all, it will be from Amazon, Costco and Walmart. ■

Leaders | How to repel talent

Pausing foreign applications to American universities is a terrible idea

The Trump administration hobbles a great American export

Photograph: EPA

May 28th 2025

Listen to this story

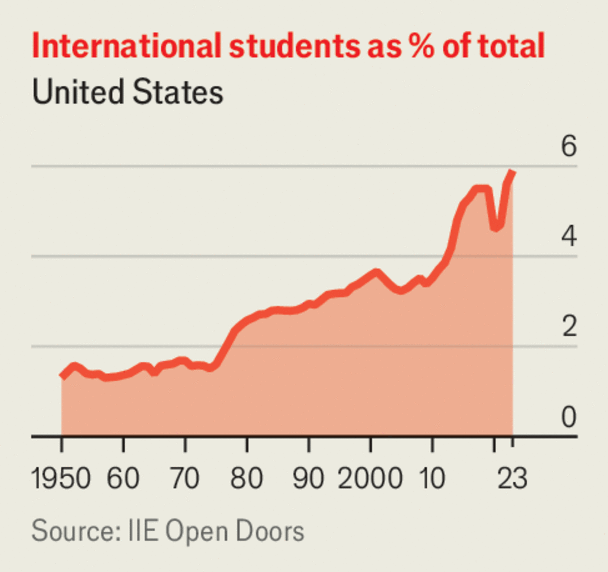

The Trump administration’s decision to pause all visa interviews for foreign students who want to study in America, pending a review of how applicants’ social-media posts are vetted, is yet another escalation in the power struggle over who controls the world’s best universities. The policy may be modified. It may prove less onerous than it looks at first glance. Even if that happens, though, this is another blow to a great American success story.

President Donald Trump cares about America’s trade deficit. So it is perverse for him to make it harder for one of America’s most prodigious exporters—the education industry—to sell its services to foreigners. Some of his supporters imagine that foreign students are taking places that could have gone to Americans. This could be called the lump-of-college fallacy. In fact, by paying higher fees, foreign students tend to subsidise locals. American universities attract a wider variety of the best minds from around the world than any of their global rivals. That makes them more dynamic and innovative. And by pulling foreign elites into America’s cultural orbit, they magnify America’s soft power abroad.

Chart: The Economist

Unfortunately, that is not how Mr Trump and his cabinet see it. To them, elite universities, in particular, are hotbeds of antisemitism and wokery. They are factories for future Democratic Party leaders and donors. And they must be brought to heel. “The universities are the enemy,” as J.D. Vance (Ohio State and Yale Law) told a conference of national conservatives before he became the vice-president.

There is some truth to MAGA criticisms of elite universities. Some have indeed been too soft on antisemitism and too dismissive of conservative viewpoints. But that hardly justifies the cudgels the administration is wielding against the entire college system. So far they include: deporting foreign students for wrongthink, freezing applications from foreign students, suspending government research grants and promising to increase taxes on big college endowments.

Mr Vance has often complained, with some justification, about censorship on campus. So it is galling for him now to favour deporting foreign students for their views and making new student applications subject to social-media vetting. College is supposed to be a place where the young explore new ideas, not a place where they venture only with burner phones, terrified to reveal they once shared a meme sympathising with Palestinians or mocking Mr Trump. The only students likely to have clean social-media feeds will be those from police states like China, who have internalised the lesson that free expression attracts unwelcome attention. Perhaps that is why the administration has also said that it will “aggressively” revoke visas of Chinese students.

In the global war for talent, America’s universities have long been its most persuasive recruiters, with huge benefits for American science, business and arts. Mr Trump’s policies will make them less attractive. Foreigners have other options. Why pay to study in a country where the president doesn’t want you, your visa could be revoked before you graduate, you will be snooped on and you may not be allowed to work?

American universities are so good that large numbers of foreigners will still jostle to attend them. However, the early signs are that all this really is deterring applicants. Mr Trump and his supporters may think that, by cutting snooty lefty institutions down to size and shutting out foreigners with distasteful views, they are making higher education in America great again. They are on course to make it mediocre. ■

Leaders | A dictator’s progress

First he busted gangs. Now Nayib Bukele busts critics

El Salvador’s president has all the tools of repression he needs to stay in power indefinitely

Photograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025

Listen to this story

Nayib Bukele’s autocratic tendencies were already clear when he ran for a second term as El Salvador’s president in 2024. He had extended a “temporary” state of emergency for two years, and used it to lock up legions of alleged gangsters without due process. He had ignored court rulings and used soldiers to bully lawmakers into supporting him. After his party won a supermajority in the legislature in 2021, he used it to stack the justice system with cronies. El Salvador’s constitution limits presidents to one five-year term, but those friendly judges waved him through. There was evidence that his government had done deals with the gangs, and bought their support in elections.

Salvadorans did not care. They re-elected Mr Bukele in a landslide, with 85% of the vote. They loved him because he made the streets safe. Gangs had terrorised the country for decades. The murder rate in 2015, at 106 per 100,000 people, was the highest in the world. Every corner shop and bus company faced the threat of extortion. Mr Bukele ended this by jailing 85,000 people, equivalent to 8% of all young men in El Salvador. Anyone suspected of gang ties—because of a tattoo, a tip-off or a policeman’s hunch—could be locked up indefinitely without trial. By 2024 the official murder rate was only 1.9 per 100,000: lower than in the United States. Extortion all but disappeared, since gangsters were too scared to show their faces.

Nayib Bukele is devolving from tech-savvy reformer to autocrat

Voters were so grateful that they overlooked the power grabs that came with all this. Only a few liberal voices warned that the strongman would one day aim his weapons of repression more widely.

One year after his re-election, he is doing just that. Journalists who report on his tyranny are being arrested, along with union leaders who question government spending and farmers protesting against land seizures. On May 18th his goons seized Ruth López, a prominent human-rights lawyer.

On May 20th his tame legislature passed a law that mimics the repression of Vladimir Putin. Any organisation that receives foreign funds or merely “responds to the interests” of foreigners must register as a foreign agent. It can then be strictly monitored and shut down on a whim. That will be crippling for human-rights groups, anti-corruption NGOs, and so on. Mr Bukele has also empowered himself to rewrite the constitution more easily. Now that the opposition has been neutered and most watchdogs are muzzled, there is little to stop the 43-year-old from remaining “the world’s coolest dictator”, as he styles himself, well into old age.

Mr Bukele has been a beneficiary of President Donald Trump’s values-free foreign policy. Whereas President Joe Biden objected to Mr Bukele’s power grabs and slapped sanctions on his allegedly corrupt or abusive associates, Mr Trump gushes that he is doing “a fantastic job”. In turn, Mr Bukele lets Mr Trump use El Salvador’s brutal prisons as a memory hole for deportees, beyond the reach of any law.

At home, however, Mr Bukele’s popularity has started to slip. Many Salvadorans dislike playing jailer for Uncle Sam. Despite safer streets, the economy is lacklustre. Poverty is rising, many public services are dismal and ordinary Salvadorans smell whiffs of grotesque corruption in high places.

Recent revelations about Mr Bukele’s cosy relationship with the gangs have been damaging, too. El Faro, a news outlet, reports that gangs helped him win his first big election, as mayor of the capital, San Salvador, and agreed to make the murder rate look lower by hiding bodies better. Mr Trump has obligingly sent back to El Salvador some gang members who were detained in America under Mr Biden and may have dirt on Mr Bukele. But silencing them will not hush up the scandal.

Polls in El Salvador are unreliable, given widespread fear of the government, but some show Mr Bukele’s approval rating far below its peak of nearly 90%. This may explain his recent crackdown on critics.

A spiral of souring public opinion and greater repression looms. However, Mr Bukele will probably weather it. He has a knack for social media, a powerful propaganda machine and all the tools he needs to crush his opponents. As Nicaragua and Venezuela show, autocrats can cling to power long after they cease to be admired.

Mr Bukele’s entrenchment as a despot holds a simple lesson, especially for other countries made miserable by gang violence, such as Ecuador and Peru. When a would-be strongman promises to keep you safe from criminals by suspending the rule of law, he may succeed for a while. But there will be no law left to keep you safe from him. ■

Asia | Compounding misery

Myanmar’s scam empire gets worse, not better

Fewer Chinese are forced to come, but more workers are coming by choice

Myawaddy bluesPhotograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025|Bangkok

Listen to this story

For Samuel, a sports teacher in Sierra Leone, a Facebook message promising a similar job in Thailand at ten times his salary was irresistible. Yet his dream curdled when he landed in Bangkok. Spirited across the border into Myanmar, he was tortured and coerced into the online-scam industry, and confined for ten months in a vast compound secured by barbed wire, high walls and armed guards. His job was to pose as an affluent Singaporean woman to defraud victims on eBay.

Deliverance, of a sort, arrived in February. He was one of some 7,000 people released from scam compounds in Myawaddy, a town on Myanmar’s border with Thailand that is among the world’s largest online-fraud hubs. According to some estimates, this industry dwarfs the global illicit-drug trade in value. The raid was a mere dent; the United Nations reckons that at least 120,000 people remain captive in such facilities in Myanmar. Globally, this illegal business may have as many as 1.5m coerced and voluntary workers, according to the United States Institute of Peace, a think-tank in Washington.

After more than two grim months in a camp in Myanmar, on May 8th Samuel was able to fly to Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital. Around 400 people, mostly from Ethiopia, remain stranded in Myawaddy. Repatriation gets tied up in red tape involving embassies in Thailand or Myanmar, when for many Africans the nearest diplomatic mission might be in Beijing or Tokyo. And many African governments are unable or unwilling to pay for a flight home. Those left behind are held in military camps or repurposed scam compounds, mostly run by the Kayin Border Guard Force, a powerful militia. Access to food and water is limited. Several people are reported to have died since February for want of medical care.

Scam operations continue to grow. Judah Tana of Global Advance Projects, an NGO on the Thai-Myanmar border, says people from around the world, including India and the Philippines, are “flocking” to the fraud compound. Many now arrive voluntarily, aware that their role will involve conning others online. Previously, most scammers’ journeys to Myanmar involved a flight to Bangkok airport, a seven-hour car ride to Mae Sot, a Thai town on the Myanmar border, and being smuggled across. Thailand has made this journey harder. Mr Tana says people have to take a circuitous route from Bangkok to Mae Sot, swapping cars around ten times.

He says fewer Chinese nationals are appearing at the border. This is perhaps unsurprising—China’s government was behind the release of Samuel and the others from scam compounds in February. In January the trafficking of Wang Xing, a Chinese actor, into a Myanmar scam compound ignited outrage in China, prompting the government to press the Thai and Myanmar authorities to act. This pressure, applied to local militias, prompted them to shed what Jacob Sims, an expert on transnational organised crime in South-East Asia, terms the “low-performing, bottom 5-10% of their workforce”. Samuel and his fellow detainees owe their freedom less to a crackdown than to a calculated pruning of the workforce. Dismantling this vast, criminal enterprise will require a much broader, sustained effort. ■

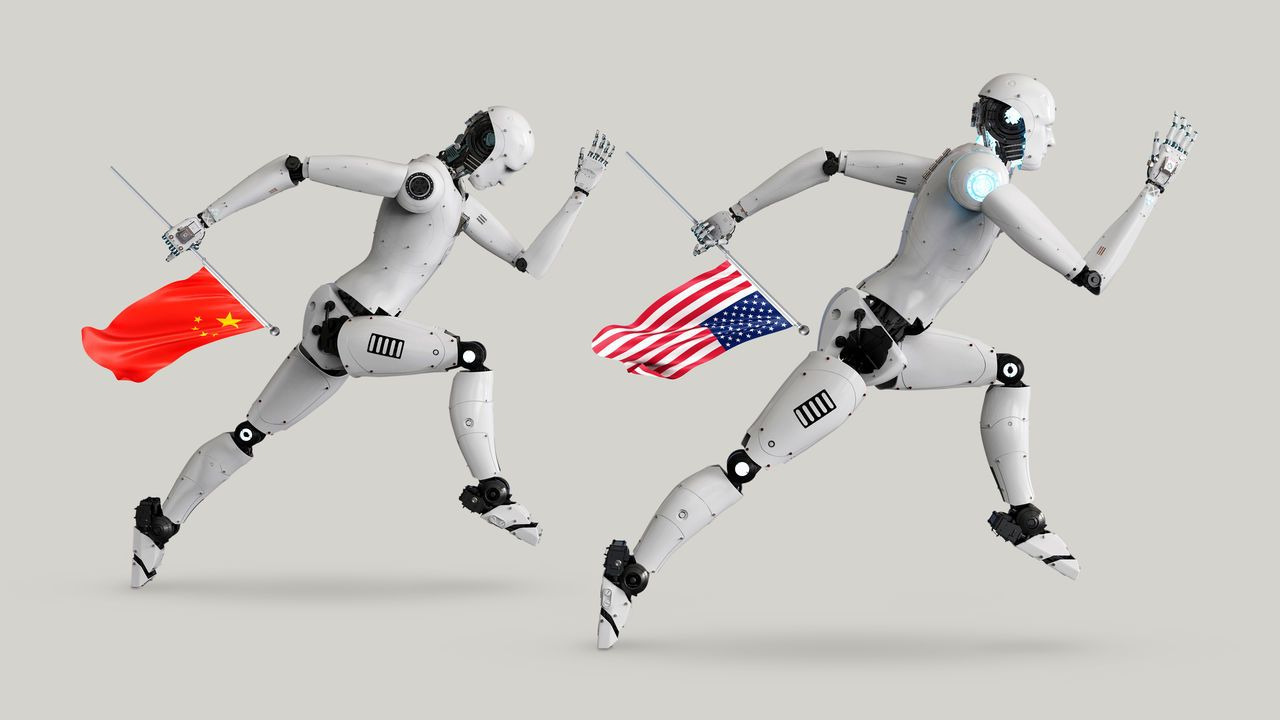

China | The superpower technology race

Xi Jinping’s plan to overtake America in AI

China’s leaders believe they can outwit American cash and utopianism

Illustration: Mariaelena Caputi/Shutterstock

May 25th 2025

Listen to this story

On May 21st J.D. Vance, America’s vice-president, described the development of artificial intelligence as an “arms race” with China. If America paused because of concerns over AI safety, he said, it might find itself “enslaved to PRC-mediated ai”. The idea of a superpower showdown that will culminate in a moment of triumph or defeat circulates relentlessly in Washington and beyond.

This month the bosses of OpenAI, AMD, CoreWeave and Microsoft lobbied for lighter regulation, casting ai as central to America remaining the global hegemon. On May 15th President Donald Trump brokered an ai deal with the United Arab Emirates that he said would ensure American “dominance in AI”. America plans to spend over $1trn by 2030 on data centres for ai models.

The “DeepSeek moment” in January, when the Chinese company unveiled a large language model (LLM) almost matching the capabilities of an Openai model, confirmed that China is snapping at the heels of America. Yet a recent meeting of the Communist Party’s leadership suggests it is preparing for a different kind of strategic race. “American firms focus on the model, but Chinese players emphasise practically applying ai,” says Zhang Yaqin, a former boss of Baidu, a tech giant, now at Tsinghua University.

This focus on practical applications—in factories and for consumers—is how China stole a lead in e-commerce and e-payments. On May 19th Jensen Huang, the boss of Nvidia, a chip firm, warned that America is in danger of being left behind again. If American firms do not compete in China as it builds a “rich ecosystem”, Chinese technology and leadership “will diffuse all around the world”, he told Stratechery, a newsletter.

America’s view of ai is often abstract and hyperbolic. LLMs are expected to match humans’ cognitive abilities. Boosters believe this Rubicon of artificial general intelligence (AGI) will be crossed quite soon. Sam Altman, the boss of Openai, reckons the next step could be superintelligent systems that actually surpass human abilities in cognitive tasks.

Being the first to develop a model that can recursively improve itself (some call this “take-off”) may create a decisive advantage comparable to a nuclear bomb. Barath Harithas of CSIS, a think-tank, notes that American planners believe “the first country to secure the AGI laurel will usher in the 100-year dynasty.” America’s export controls on semiconductors are there to ensure China comes second.

It is true some Chinese entrepreneurs are also believers in the arms race. Liang Wenfeng, DeepSeek’s founder, has made developing agi his firm’s mission and reckons it may arrive in as little as two years’ time. Less noticed is that the government is betting on a different approach.

Mr Liang’s exploits won him a meeting with Li Qiang, the prime minister, in January. But days later a vice-premier in charge of the party’s science effort seemed to rebuke the American approach, stating: “China will not blindly follow trends or engage in unrestrained international competition.” Last month Qiushi, an authoritative party journal, described AGI as a tool “to promote human understanding and transformation of the world”. In China the term for AGI, tongyong rengong zhineng, typically refers to a “general-purpose AI” that is applied and has multiple uses, rather than to the Western concept of a superhuman, or self-improving, system.

In April the party’s Politburo met for its second-ever study session on AI (the first was in 2018). At the meeting, President Xi Jinping told his lieutenants they should focus on how it can be applied to everyday uses: more like electricity than nuclear weapons. At least a dozen prominent researchers and government officials have aired scepticism over the reasoning ability of LLMs. Wu Zhaohui, a former minister of science and the current vice-president of a state think-tank, suggests China needs to explore different paths to AGI. Chinese experts generally expect AGI to take longer to arrive than do their American counterparts, notes Mr Zhang of Tsinghua.

“While American tech leaders often frame AI with Utopian aspirations, China’s government appears more focused on using it to solve concrete problems like economic growth and industrial upgrading,” says Karson Elmgren of RAND, an American think-tank. The government’s annual work report in March mentions a new campaign called “AI+”, which prioritises firms adopting AI, including in physical facilities using automated robots.

A protracted war

This application-oriented approach reflects a shortage of ai talent and chips, or “basic theory and key core technologies”, Mr Xi said in April. “We must face up to the gap.” Liu Zhiyuan of Tsinghua University compared China’s approach to an argument in “On Protracted War”, a series of lectures by Mao Zedong in 1938: a weak opponent can tire, and outlast, a strong one. On May 8th Qiushi published an article by Tang Jie, also of Tsinghua, urging China to follow American innovation and create applications cheaper and faster.

China’s emerging AI strategy seems to have two parts. One is to undercut the monopoly America has over advanced ai, by replicating Western innovations and making the model weights freely available, or “open source”, as DeepSeek has done. The idea is that the value AI generates will accrue to those who apply it, not to the model-makers. By the time AGI arrives, China will be better placed than America, with “robust social applications, search engines, agents and hardware in place,” notes Kai-Fu Lee, a prominent Beijing-based entrepreneur. He argues that by amassing users and data early, Chinese applications can build a moat that Western competitors will struggle to cross, just as TikTok, a video app, has done.

Alongside the push to deploy ai faster and more cheaply, there is an effort to create moonshots that bypass America’s trillion-dollar bet on LLMs. “If we merely follow the well-worn American path—computing power, algorithms, deployment—we will always remain followers,” said Zhu Songchun, boss of the Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence, a state-run laboratory dedicated to advanced ai, in a speech last month. In April the Shanghai government offered funding for researchers advancing towards AGI using new kinds of architectures, such as models that interact with the real world through imagery, others that can control computers with the mind, or algorithms to emulate the human brain.

Will China’s approach work? A new IMF study concludes ai could boost America’s economy by 5.6% in ten years’ time, compared with 3.5% for China, largely because China’s relatively small services sector means that, even if ai diffuses fast in manufacturing, the productivity gains are capped. Yet what is clear is that China is accelerating down a different track. One sign of this is Apple: in order to reverse a decline in its revenue in China, it desperately needs a local partner to provide ai services which customers now expect. But reports suggest America may block it from doing so. Without local ai applications, American tech products, such as the iPhone, risk becoming also-rans in China, and perhaps, in time, elsewhere. ■

United States | The Zillennial election

How young voters helped to put Trump in the White House

And why millennials and Gen Zers are already leaving the president

Photograph: Getty Images

May 27th 2025|BOSTON

Listen to this story

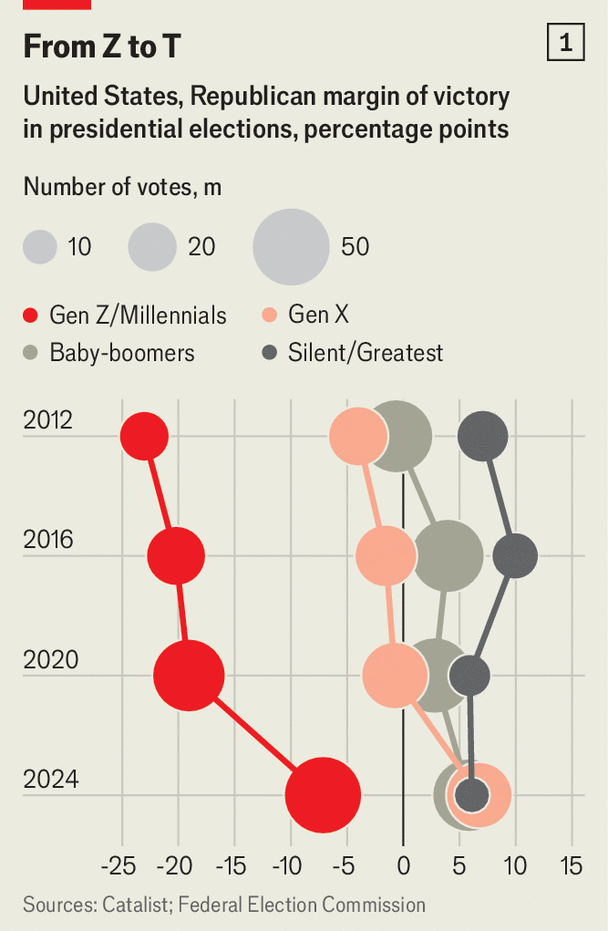

THE 2024 election unfolded like a political thriller, replete with a last-minute candidate change, a cover-up, assassination attempts and ultimately the triumphant return of a convicted felon. But amid the spectacle, a quieter transformation took place. For the first time, millennials and Gen Z, people born between 1981 and 2006, comprised a plurality of the electorate. Their drift towards Donald Trump shaped the outcome.

Millennials and Gen Z are the most diverse and educated generations in American history, traits long thought to favour the Democratic Party. Yet a new report from Catalist, a left-leaning political-data firm, shows that although Democrats still won a majority of young voters, their long-standing advantage over the Republican Party was reduced by nearly two-thirds. In 2024 Kamala Harris’s margin of victory among these voters was 12 points smaller than was Joe Biden’s in 2020, a bigger swing than for any other cohort (see chart 1). The exodus was caused in large part by non-whites and helped propel Mr Trump back into the White House. But many of these voters lack firm partisan loyalties. They are still up for grabs.

Chart: The Economist

Younger voters appear highly sensitive to economic pressures. They earn less than their elders and are less likely to own their home or have substantial savings. America’s overall unemployment rate was a healthy 4.2% in November 2024. But the figure was nearly double that for 20- to 24-year-olds and roughly triple that for 18- and 19-year-olds. Younger voters were more likely to say that the economy was the most important issue to them and substantially less likely to cite immigration.

Catalist’s numbers are only available six months after the election, and their analysis avoids many of the pitfalls that plague pre-election polling, which underestimated Mr Trump for the third consecutive presidential election. The average American voter swung towards Mr Trump by six points in 2024. The lion’s share of that shift came from the youngest voting-age generations. Gen Z and millennial voters preferred Mr Biden by 19 points in 2020.

Had these two cohorts voted as they did in 2020, Ms Harris would have won the popular vote by 2.8 points, rather than losing it narrowly to Mr Trump. And though turnout fell by around two points nationwide, it fell by double that among 18- to 29-year-olds. This also hurt Ms Harris, since she attracted a majority of the young vote, even if by declining margins.

Most worrisome for Democrats is their clear loss of purchase on younger black and Latino voters. Though Democrats have long hoped that a more diverse young electorate would help tilt the political map in their favour, the latest data show that it was those voters who revolted most fiercely. Among 18- to 44-year-olds, white voters swung towards Mr Trump by 4.6 points, while their black counterparts shifted by 14.6 points and Latinos by a sobering 22.6 points. The impact was all the greater because just under a third of millennials and Gen Z are non-white, a higher percentage than for older generations.

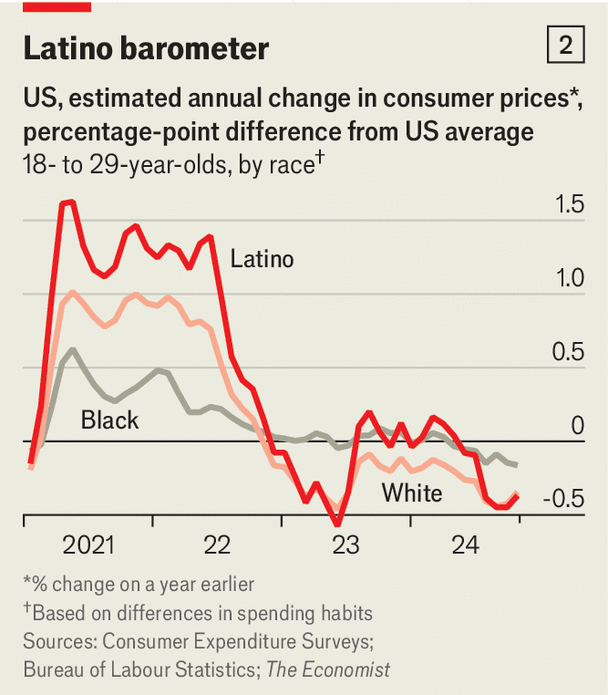

Chart: The Economist

One reason all groups of young people swung against the Democrats in 2024 seems to be their perceptions of the economy. In polling conducted by YouGov/The Economist before the election, 18- to 29-year-olds gave Mr Biden a net rating of minus 23 percentage points on his handling of inflation, for example. Indeed, The Economist’s analysis of the Consumer Expenditure Surveys found that young people’s consumption habits meant they were exposed to higher rates of inflation in 2021 and 2022, when prices were rising at their fastest (see chart 2). The Fed reports that used cars and fuel make up a larger portion of young people’s (and especially Latinos’) spending. Prices for those goods rose dramatically in 2021 and 2022.

Yet economic stress is not the only plausible explanation for young voters’ desertion of the Democratic Party. They are also more likely to consume news from non-traditional sources. YouGov’s pre-election polling showed that six in ten young people had learned something new about Mr Trump from social media; one in four had heard new information about him from podcasts. In the final days of the campaign Mr Trump went on a tour of “bro podcasts”, fishing for viral moments. Social media were also a hotbed for left-wing criticism of Mr Biden and Ms Harris, especially of their handling of the conflict in Gaza. Analysis by Blue Rose Research, a Democratic firm, found that voters who got their news from TikTok were substantially more likely to switch to the Republican Party, even after controlling for other factors.

Chart: The Economist

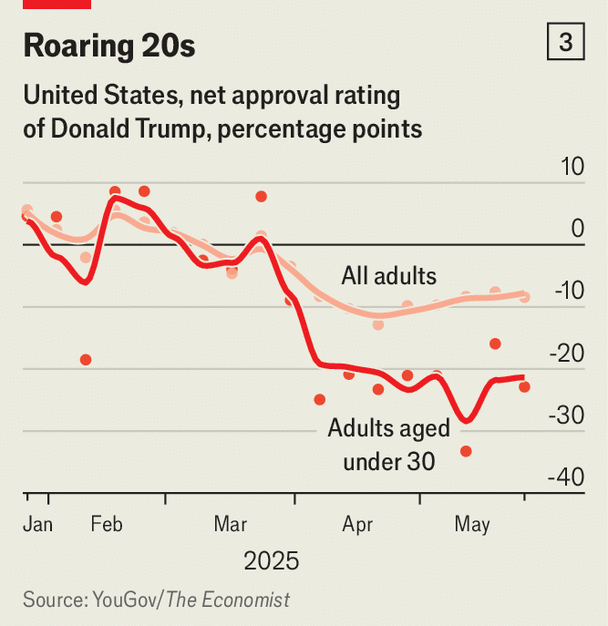

Perhaps the only good news for Democrats is that millennial and Gen Z voters appear persuadable. Already, data from YouGov/The Economist show that many of the gains Mr Trump made for his party among the youngest voters have begun to diminish. After a chaotic first few months in office the president’s net approval has fallen by around 13 points nationwide. Among the under-30s it has plunged 25 points, from net positive four to a net negative 21 (see chart 3).

Research by Columbia University found that events in voters’ early adulthood have an outsize effect on their long-term partisanship. Older millennials aged into the electorate against the backdrop of the financial crisis and Occupy Wall Street. But for the youngest voters formative political events have been more diverse and disruptive. They have come of age during covid-19 lockdowns, cost-of-living shocks and the rise of and backlash against wokeness. How they will make ideological sense of the whiplash is difficult to predict. ■

The Americas | Otherworldly success

Why Latin American Surrealism is surging in a down art market

Works by women in particular offer collectors a sure thing at a better price

Photograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025

Listen to this story

In 1956 the painter Diego Rivera stated that three of the world’s most important female artists lived in Mexico. (His wife, Frida Kahlo, had just died.) He was talking about European émigrée Surrealists: Remedios Varo of Spain, Leonora Carrington of England and Alice Rahon of France.

Unlike Kahlo, whose face appears on cushions and in baby books, Varo, Carrington and Rahon are little known outside the art world. But demand for their work has driven surging prices that collectors are willing to pay for works by female Surrealists, particularly those from Latin America.

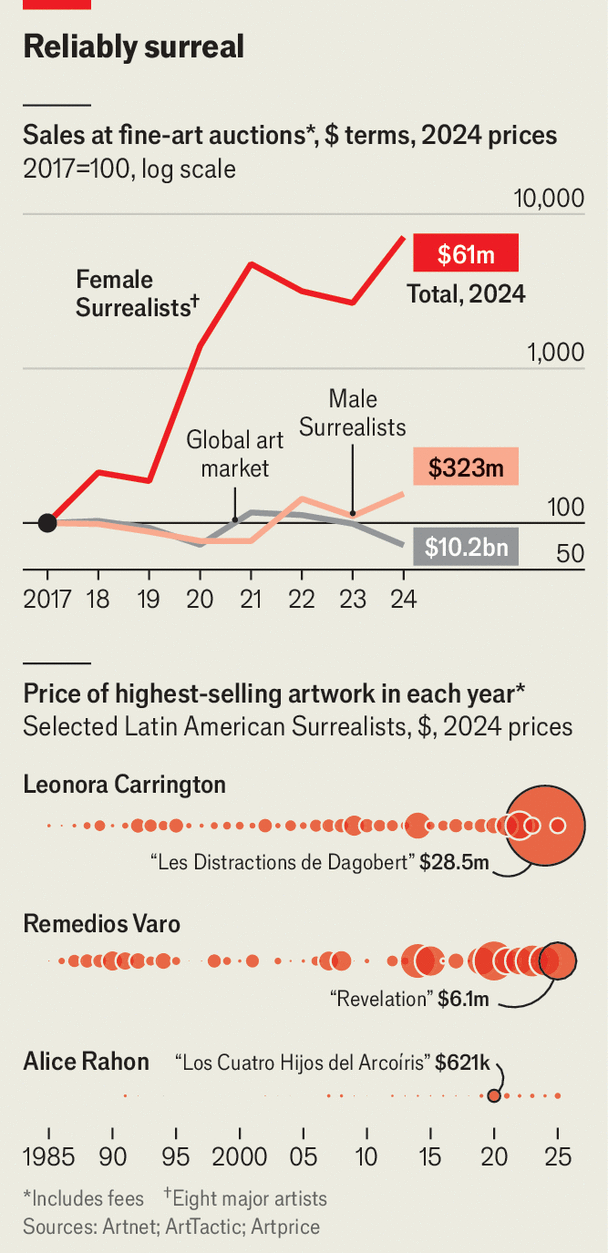

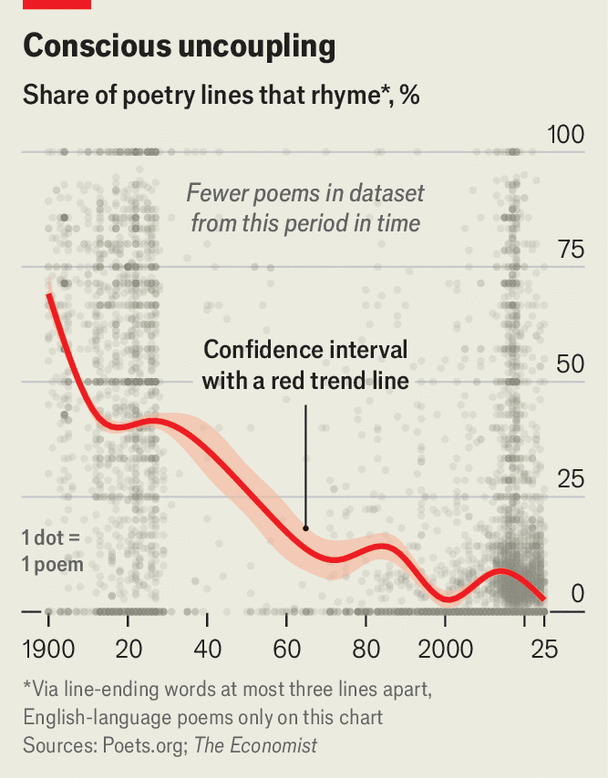

Chart: The Economist

Between 2017 and 2023 total sales of works by the eight major female Surrealists increased in value by an average of 150% every year, according to ArtTactic, an arts consultancy based in London (see chart). In 2024 sales jumped by 159%, mainly thanks to Carrington and Varo, together up 490%. Argentine collector Eduardo Costantini paid $28.5m for a Carrington, “Les Distractions de Dagobert”, coming close to Salvador Dali’s top price. All this amid a slumping global art market. Overall sales were down by 27% last year.

The boom has its roots in the 1940s, when many European artists fled to Mexico to escape fascism. André Breton, a French founder of Surrealism, hailed the country as “the Surrealist place par excellence”. A magical mentality has long been embedded in indigenous Mexican culture, according to Janet Kaplan, an art historian, exemplified by the sugar-coated confectionery skulls given to children for the Day of the Dead. Where they had been peripheral in Paris, perhaps crowded out by male peers, once in Mexico Varo, Carrington and Rahon rose to become major artists.

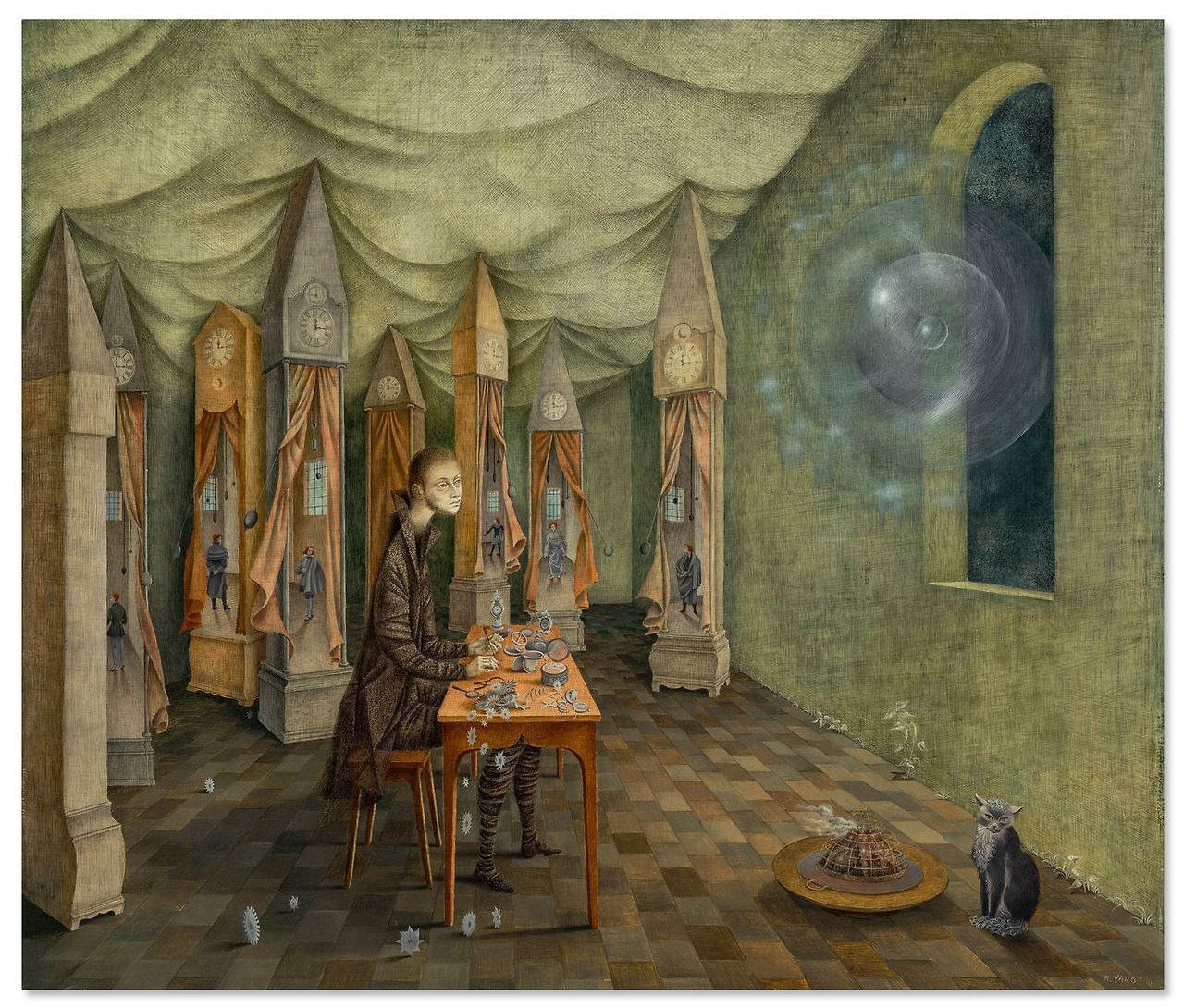

Remedios Varo, Revelación (also titled El relojero)Photograph: Christie's Images Ltd. 2025

As the value of everything from the dollar to tech stocks shifts, collectors have focused on established work. “Ultra-contemporary” art was hot in 2022, but prices dipped by 38% in 2024, falling more than the overall market. In contrast, a painting by René Magritte was sold in New York for $121m in 2024, a record both for the artist and Surrealist work. For collectors who want a sure thing, but who cannot afford the most famous pieces, the female Surrealists offer a discounted way to hedge risk, says Lindsay Dewar of ArtTactic.

Nationalist-billionaire ambition also pushes up prices. Mr Costantini founded the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires and wants pieces to fill it. His bidding wars can send prices sky-high. After paying a record price for a Varo in 2020, he said: “It can take 50 years to see [such superlative works] again.”

Institutional recognition has also played a role. In 2021 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York put on an exhibition which expanded Surrealism’s canon beyond western Europe. It included pieces by Carrington, Varo and Rahon.

Major works are rarely sold, but on May 12th Christie’s in New York auctioned Varo’s “Revelation” for $6.22m, a new record for the artist. The painting depicts gears of a clock scattered amid a glowing disc, representing Einstein’s relativity. Born from geopolitical tumult, Surrealism focused on the subconscious and otherworldliness. “It’s 100 years later,” says Ms Dewar, “and things kind of feel the same”. ■

Middle East & Africa | On the sidelines

The losers of the new Middle East

The tables have been turned on once-powerful countries

Photograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025|DUBAI

Listen to this story

EIGHT YEARS ago Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi was on centre stage. Donald Trump gave the Egyptian dictator a warm welcome at the White House in April 2017. A few weeks later, when Mr Trump visited Riyadh, the Saudis invited Mr Sisi to join. The former general, who seized power in a coup in 2013, took pride of place alongside the American president and the Saudi king at the launch of a counter-terrorism centre.

Yet no one bothered to summon him when Mr Trump returned to Riyadh this May. Gulf rulers were keen to talk to the American president about their vision for the Middle East, and Mr Sisi did not fit into those plans. Instead he flew to Baghdad for a desultory Arab League summit, where he was one of only five heads of state to attend (most members of the 22-country club sent mere ministers).

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

This is a moment of transition in the Middle East. Iran is weakened. New governments in Syria and Lebanon want to keep it that way. Gulf monarchs are keen on detente with both Iran and Turkey, their regional rivals. Mr Trump talks hopefully of a “bright new day”, a Middle East focused on commerce rather than conflict.

The region is a rough place for optimists: this moment may not last. Whether or not it does, it shows how the Middle East has already changed. Rich and seemingly stable, the Gulf states are at the hub of things, while some countries that were once influential are now just onlookers.

At the top of that list is Egypt, and Mr Sisi has himself to blame. He has wrecked the Egyptian economy, running up unsustainable public debts (around 90% of GDP) to pay for vanity projects and refusing the common-sense reforms that might boost a stagnant private sector.

That has left Egypt reliant on bail-outs. It has received at least $45bn in aid from Gulf states since 2013, according to data from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank. It is also the IMF’s third-biggest debtor. But now it has competition. Lebanon will need at least $7bn to rebuild after last year’s war with Israel. Syria will need many times more.

At least for now, both countries seem a better investment than Egypt. Their governments are promising serious economic and political reform. Syria’s interim government wants to privatise state-run firms and woo foreign investors. Joseph Aoun, the Lebanese president, wants to disarm Hizbullah, a powerful Iranian-backed militia. Aid to those countries might help them achieve those goals; aid to Egypt merely buys time until its next financial crisis.

Iraq finds itself sidelined too. Iran has lost its closest state ally (the Assad regime in Syria) and its strongest proxy militia (Hizbullah). That leaves it desperate to preserve its influence in Iraq, where it supports an array of armed groups. Some officials in the Gulf describe Iraq as a lost cause: the militias are too strong and too interwoven with the state to be uprooted. Ahmed al-Sharaa, Syria’s new president, could not even attend the Arab League summit in Baghdad because of threats from pro-Iranian militias.

No matter: he flew to Riyadh instead, where he met Mr Trump and secured a promise that America would lift its sanctions. The Saudis are keen to support Mr Sharaa in part because a strong Syria would be a bulwark against Iranian influence. “Syria used to help balance Iraq,” muses one Saudi official, referring to a time when the Assad regime was a rival of Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship in Iraq. “Maybe it can play that role again,” this time with Iran.

The stateless Palestinians have been at the heart of Arab affairs since 1948. But there is reason to think that they too are losing their centrality. Mahmoud Abbas, the eternal Palestinian president, has done nothing to clean up his corrupt administration in the occupied West Bank. Hamas offers an even bleaker model in Gaza: it has let Israel destroy the enclave rather than cede power.

Arab leaders still pay lip service to the Palestinian cause. In practice, though, they are trying to diminish its influence. Mr Aoun wants to disarm the Palestinian militias in Lebanon’s refugee camps (and some members of Hizbullah have signalled their assent). The new Syrian government has pledged to do the same. There is serious talk in both countries about peace with Israel: not full normalisation, but at least an end to decades of conflict.

All of this makes for a remarkable turnabout. A year ago Lebanon and Syria seemed like lost causes as well. The former was dominated by Hizbullah and at war with Israel; its economy was still reeling from a financial crisis that shrank its GDP by 40%. The latter was a narco-state still in the grips of a resilient-looking Assad regime. Now Gulf states and America see them as the heart of a more prosperous Middle East. To stay that way, their governments will have to deliver results.

After all, many of Mr Sisi’s Arab allies had high hopes for him too a decade ago. Those hopes were dashed. For decades, the Middle East was divided along ideological lines. Perhaps now the split is between governments that can meet their promises and those that cannot. ■

Middle East & Africa | Cultural globalisation

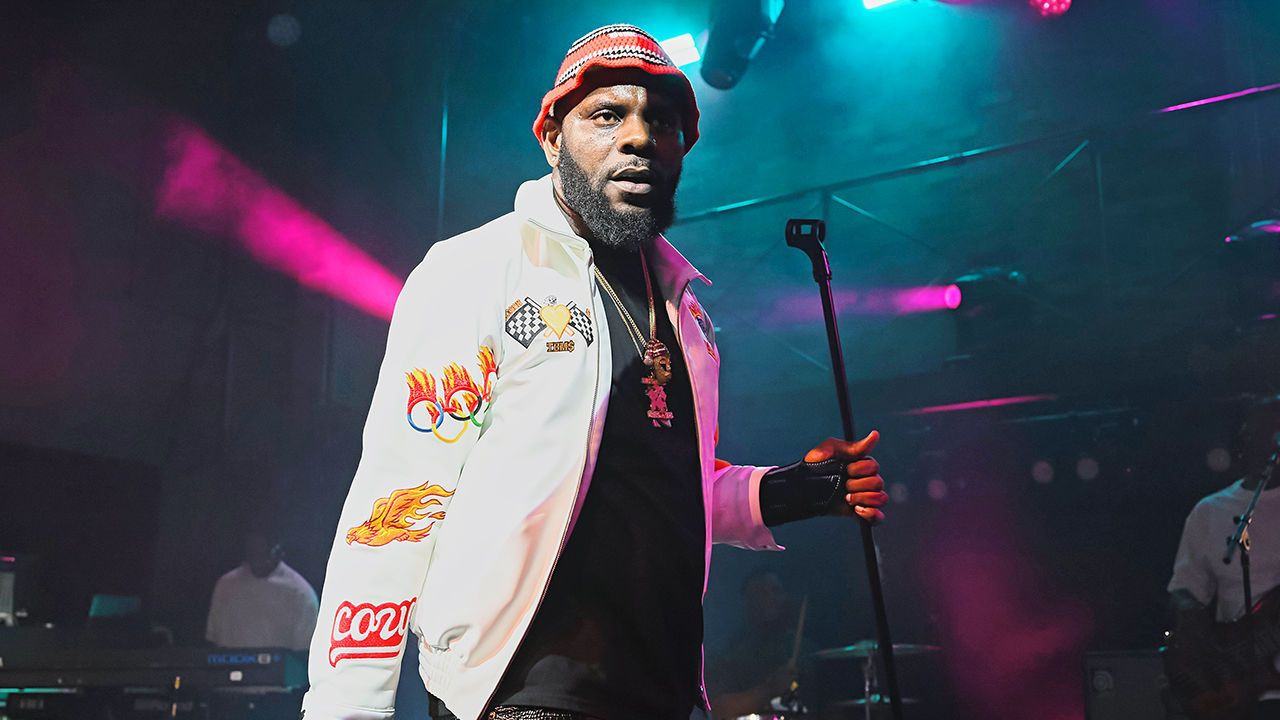

Afrobeats’ new groove

Africa’s growing diaspora is transforming the continent’s musical exports

From Abuja to the worldPhotograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025|Lagos

Listen to this story

IN 2023 ODUMODUBLVCK, a Nigerian rapper and singer, put out his first single. Called “Declan Rice” after an English footballer, the track saw a fresh surge in streams in April when Mr Rice scored two free kicks for Arsenal in a tense match against Real Madrid. On the record the artist, brought up in Abuja as Tochukwu Ojugwu, layers Pidgin English on a drill track to liken Mr Rice’s game-changing star power to his own. Since its release he has signed with Native Records, a Nigerian label based in Britain, and has put out a mixtape featuring an Italian rapper that has proved popular from Britain to Qatar.

Living and working across the world, Odumodublvck typifies a new generation of African musicians who in recent years have won global awards, topped international charts and rocked stages from India to Brazil. Spotify, a streaming platform, found that streams of what is referred to as Afrobeats increased more than six-fold between 2017 and 2022, and by 33% in 2024 alone. As African music has spread around the world, it has also acquired more varied influences and a more diverse sound, partly thanks to its changing audience. Afrobeats now refers to a range of styles that is hard to capture in a single word, changing the business.

The popularity of African music is not new. African acts from King Sunny Ade, a Nigerian juju singer, to Amadou & Mariam, a Malian blues duo, have played on festival stages in America and Britain since the 1970s. But as diasporas have grown, some African artists now perform abroad more often than at home. Yoruba slang and Zulu call-and-response loops echo from London’s O2 arena to New York’s Madison Square Garden. This summer Rema, one of the world’s most streamed African artists, will headline Japan’s first-ever Afrobeats festival, performing alongside Ghanaian, South African and Jamaican acts.

As audiences have expanded, the music has changed. Songs are a fraction of the length of Fela Kuti’s 15-minute ensembles from the 1980s, made more digestible for a generation of TikTok dancers who often discover new sounds on social media. The tracks are sped up to sound more poppy or slowed down to marry better with R&B. Lyrical rap and underground music lean heavily on American hip-hop. Cross-genre collaborations, samples and interpolations have become the norm.

Rema featured Selena Gomez, an American pop singer, on a remix for his 2023 hit “Calm Down”. It became the first song led by an African artist to exceed 1bn streams on Spotify. Within the continent, artists in Nigeria have lifted from, and collaborated with, Amapiano hitmakers in South Africa, who slow down European drum-and-bass beats and fuse them with log drums and local languages. “Pop borrows from other genres. Afropop is nothing different,” says Seni Saraki, who runs Native Records (and prefers the moniker Afropop to Afrobeats).

A more global sound has brought a more global ownership. Spotify paid 58bn naira ($36.5m) to rights-holders of Nigerian music in 2024. Because many artists and their labels have links with global firms, little of that stayed in Nigeria. And while global reach has brought commercial success for some, it has also meant less creative control. “We need the money and we need the connections, so it’s a bit of a sacrifice,” says Joey Akan, a podcaster.

Change your tune

Artists earn more from streams in richer countries than in poorer ones. Spotify says this is because royalties are proportional to subscription prices which, based on the currencies’ purchasing powers, vary widely across countries. A premium subscription costs around $2 a month in Ghana, but $17 in Switzerland. The financial benefits of producing music that does well in the West can sway artistic choices made in the studios, sometimes to the detriment of an artist’s identity. “The songs were not picked by me, I wasn’t in the right place,” Davido, a Nigerian-American singer, later recalled of a collaboration with Sony.

The diversification of African music reflects its success in shaping global pop culture. Yet for now, African countries are benefiting less than they could. By investing in concert infrastructure, improving protection of intellectual property and developing the skills of young musicians, they could help ensure that Africa’s musical appeal is as good for the continent as it is for the rest of the world. ■

Middle East & Africa | Murder in Birakat

What a massacre reveals about Abiy Ahmed’s Ethiopia

The killing of civilians is part of a disturbing pattern

Photograph: Getty Images

May 29th 2025|Nairobi

Listen to this story

Two months ago, in the early afternoon of March 31st, gunfire erupted in Birakat, a town in the Amhara region of northern Ethiopia (see map). Panicked residents ran for cover as the Ethiopian army battled local militias. Five hours later the guns fell silent, briefly. But after the army had taken control of the town, according to three eyewitnesses, a massacre began.

Map: The Economist

In teams of four to six men, the soldiers combed through the town, dragging people from their homes and rounding them up in the streets. One man saw four women made to kneel outside the bus station, with their hands behind their heads. Four soldiers then shot them from behind. The same man later watched a different group of soldiers kill a priest outside his church. Another witness, returning to Birakat the following morning, saw piles of corpses in the streets. He counted 56 bodies, his brother among them. The Ethiopian army did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story.

The events in Birakat add to mounting evidence that what is unfolding in Amhara resembles the abuses committed by the army and other armed groups during the war in Tigray, the region next door, where hundreds of thousands of people were probably killed between 2020 and 2022. They also shed light on the increasingly reckless approach to security taken by Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s prime minister since 2018.

Since 2023 Ethiopia’s government has been in conflict with the Fano, a loose coalition of rebel groups that claim to be fighting for the interests of the Amhara, Ethiopia’s second-largest ethnic group. The government has trained and equipped local militias to help its soldiers fight them. Yet the anti-Fano fighters are also Amhara, and there is little trust between them and the regular army. Asres Mare Damte, a Fano commander, claims plenty have defected to join the Fano.

The forces with which the government clashed in Birakat on the day of the massacre were anti-Fano militias, some of whom, Mr Asres claims, have since joined the rebels. It is plausible that Ethiopian soldiers, suspecting local militias of collaborating with their enemies, sought revenge by killing anyone they could find.

That fits a disturbing pattern of reprisal attacks against civilians. In January 2024 government troops summarily executed dozens of civilians in the town of Merawi, some 20km west of Birakat, according to an investigation by Human Rights Watch (HRW), an international monitor. Those killings followed an attack by the Fano on government forces.

During the war in Tigray the Ethiopian army killed at least 70 civilian men and boys in the town of Bora, according to a UN investigation, after an attack on their camp by Tigrayan rebels in December 2020. The following month Ethiopian troops frogmarched dozens of unarmed Tigrayan men to the edge of a cliff near the town of Mahbere Dego, where they filmed themselves shooting their captives and flinging their corpses over the precipice. On May 14th of this year the African Union’s human-rights body held a hearing in a case accusing the army of extrajudicial killings, torture and sexual violence in Tigray.

Mr Abiy’s spokesperson declined to comment on this story. The government has previously denied that its soldiers committed atrocities in Tigray and promised to investigate individual instances of alleged abuses. It says it is preparing to launch a transitional-justice programme to prosecute all war crimes committed in Ethiopia since 1995. But independent observers say the process is a charade. “Ethiopia has stalled and hampered any hope that those most responsible will be held to account,” says Laetitia Bader, HRW’s Horn of Africa director.

In part, civilians are suffering the consequences of Mr Abiy’s approach to holding the country together. Since 2019 his army has been bogged down fighting various ethnic insurgencies. Some of his generals have publicly complained that their troops are exhausted.

Mr Abiy has repeatedly tried to solve the problem by drafting in poorly trained militias. This has tended to backfire. The Fano, for instance, were Mr Abiy’s allies during the war in Tigray before becoming his enemies. In Oromia, which borders Amhara, his government relies on a dizzying array of Oromo militias to fight the Oromo Liberation Army, another ethno-nationalist rebel group. Rebels and militiamen have been known to swap sides. Many are bandits more than fighters. Murder, theft and kidnapping are rampant.

The anarchy allows Mr Abiy to divide and discredit his enemies, which arguably strengthens his hand. But it also erodes the authority of the Ethiopian state, potentially threatening his grip on power. Mr Abiy may see method in the madness. Ethiopians are paying the price. ■

Europe | Catholics in France

France’s improbable adult baptism boom

A secular country returns to the church

Photograph: Alamy

May 26th 2025|PARIS

Listen to this story

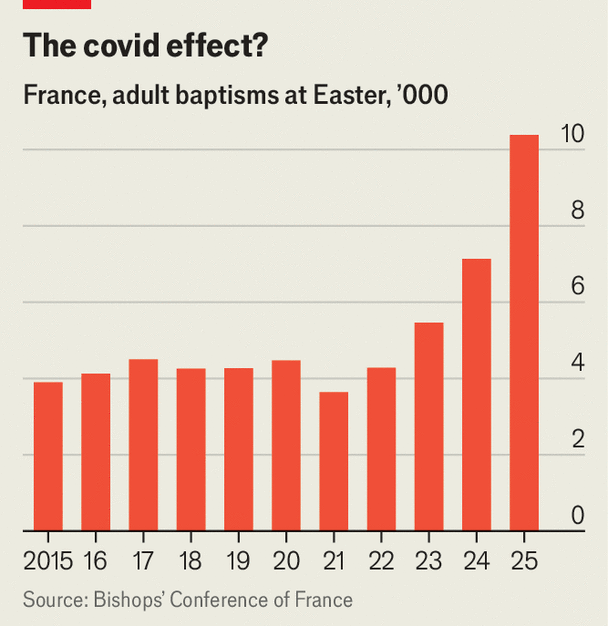

Among European countries with Catholic roots, France wears its religion lightly. A secular state by law since 1905, the country bans conspicuous religious symbols in state schools, town halls and other official buildings. Less than 5% of its people attend a religious service every week, compared with 20% in Italy and 36% in devout Poland. Yet France, of all places, is witnessing an unexpected surge in Catholic fervour.

At Easter 10,384 adults were baptised, a jump of 46% on last year and nearly double the number in 2023. This was the highest since France’s Conference of Bishops began such records 20 years ago. At 7,404, the number of teenagers baptised this Easter was more than double the figure in 2023, and ten times the one in 2019. France is not the only European country to report an upsurge in adult baptisms. Austria and Belgium this year also reported a big rise, but to a tiny total of 240 and 536 respectively. It is the scale and context that make the trend in France so arresting.

Chart: The Economist

One broad explanation may be the lasting effect of covid-19, imposed solitude and the quest for purpose that confinement generated. Some people took up yoga; others, God. The surge in baptisms in France began in 2023, two years after the end of the lockdown, which happens to be exactly the prescribed length of preparation for adult baptism. Sonia Danizet Bechet, who grew up in an atheist family in France, says that covid was the spark that moved her to begin the catéchuménat (the path to baptism).

Excessive time spent on screens (and working from home) could be another factor. People may now be seeking a non-virtual community. Nearly a quarter of adults baptised at Easter in France in 2024 were students (the rest were a mix of both white-collar and blue-collar); 36% were aged 18-25; three-fifths were women. Strikingly, nearly a quarter came from a non-religious background. “We work with a lot of people who grew up with no experience of faith and feel something is missing,” says a lay Catholic who accompanies those preparing for baptism in Paris.

But why France? After all, its Catholic church has been damaged by home-grown sexual-abuse scandals. Many churches struggle to put bottoms on pews, or priests in the pulpit. Some point to the spiritual effect of the fire that gutted Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris in 2019, and the painstaking and transcendently successful project to rebuild it—a form of resurrection and an invitation to faith, according to its chaplain. Others suggest a link to the prominence of Catholic-nationalist politicians; a pushback against France’s strict secular culture; or even an unspoken rivalry with Islam in a country with a big Muslim population.

France does not share America’s starry, big-teeth televangelist culture. Yet even here some younger priests have become mini online stars, helping to spread the word—and prompting the odd clash with the church’s staid hierarchy. Frère Paul-Adrien, a bearded Dominican monk with half a million YouTube followers and an acoustic guitar, is one such influenceur. At Easter he says he received an average of five baptism requests a day: “We are overwhelmed by what is taking place.” ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Europe fantasises about an “Airbus of everything!” Can it fly?

From chips to satellites Euro-champions are back. Expect turbulence.

Illustration: Peter Schrank

May 29th 2025

Listen to this story

What do fertilisers, artificial intelligence, small cars, microchips, vaccines, nuclear plants, streaming platforms, cloud computing, satellites and green technology all have in common? Trick question, to which the answer is not that the European Union would like to regulate them to oblivion (though there may be that, too). What links them together is that they are all sectors some in Europe think could be transformed by One Neat Trick: to create an “Airbus of”. Merging lots of subscale European companies so they stopped competing against each other and took on Boeing instead worked wonders in the 1970s; from a standing start Airbus went on to outsell its jetmaking American rival. Could the same strategy be used to help Europe in the 2020s take on the likes of Google, Nvidia, SpaceX and Chinese carmakers? Politicians in Brussels and beyond want to believe. As the pilot of a wayward Airbus might exclaim: “Brace for impact!”

No European industry confab is complete these days without someone invoking the “Airbus of” trope. To many the age of such European champions feels overdue. Even as the EU’s economies have come together in theory, it is notable how often their corporate leading lights have not. Europe’s bigger countries (and many smaller ones) all have their own energy majors, telecoms firms, banks, carmakers and so on. Some blame this enduring fragmentation on the bloc’s incomplete single market, which means that doing business across EU borders is still hard. Others focus on regulation, notably the club’s antitrust rules that stymie mergers dreamed up by industrialists. Siemens and Alstom, two big engineering firms from Germany and France respectively, pitched the “Airbus of rail”, only for it to be kiboshed by Brussels officialdom in 2019. Either way Europe is now a corporate also-ran. The EU makes up one-sixth of the global economy, yet it does not have a single firm among the world’s most valuable 20.

A few cross-border tie-ups have taken place: Peugeot of France and Fiat of Italy became Stellantis in 2021 (its biggest shareholder also owns a stake in the parent group of The Economist). Fighter jets and missiles are made through consortia of firms dotted across Europe. But politicians have more than mere mergers in mind. For Airbus is not just big, it is the apotheosis of corporations fulfilling a vision dreamed up by politicians (the firm is partly owned by the French, German and Spanish governments, though run mostly free of interference these days). Forget the jet age: Europe now needs gigafactories making microchips, green tech firms to help decarbonisation and so on. The bigger the business in Europe, the more politicians can lean on it to do their bidding. If a few new factories can serve as a backdrop for their ribbon-cutting photo-ops, so much the better. Le business, c’est moi!

Such industrial policy was once all but verboten in the EU, at least since its heyday in the age of disco music and stagflation five decades ago. Germans, abetted by Britain, imposed on the EU its largely hands-off approach to letting firms compete in the market; the French shelved their meddling instincts in exchange for farm subsidies. But dirigisme has been threatening a return for some years. The rise of Chinese industry—once a customer of German firms, now their rival—is evidence (to some) that state capitalism works. Brexit deprived the EU of a liberal voice. Covid-19, the war in Ukraine and two bouts of Trumpism have given credence to the French idea Europe needs to bolster its “strategic autonomy” by being less reliant on globe-spanning supply chains. Who wants to rely on today’s America for cloud computing, or jet fighters?

The effects of this statist turn can already be seen. Brussels once worked to deter governments from funding favoured enterprises. Now it allows giant exemptions for industries it deems “strategic”, such as batteries, microchips or hydrogen, which receive billions in cash from the EU and governments. Airbus and Thales of France and Leonardo of Italy, all partly state-owned, are lobbying for approval to merge their satellite-launch offerings (“the Airbus of satellites”, featuring Airbus). The antitrust commissioner for a decade until November, Margrethe Vestager, argued that reducing competition in Europe would make it less likely its firms could successfully compete outside it. The views of her replacement, Teresa Ribera, are thus far hard to fathom.

The boss of Airbus itself, Guillaume Faury, says that “When we work together, not against each other in Europe, we can achieve the scale needed to become global leaders.” But what worked for Airbus in the age of vinyl may not be the right recipe for tech in the age of ChatGPT: making jets is unique in that fixed costs (to design planes that actually fly) are sky high and demand for products is stable for decades. That applies to relatively few other industries. Already a bunch of grands projets have gone awry. Northvolt, a battery maker backed in part by EU and German money (“the Airbus of batteries”, inevitably), has gone bust despite raising $15bn. Gaia-X, an “Airbus of cloud computing” has failed to offer a credible European alternative to Amazon and Microsoft.

Please fasten your seat belts

In an ideal world, European pols would love to shower companies with money, Chinese-style. Alas state coffers are empty. Bar Germany, big EU countries have massive debt piles and need to find cash to spend on defence, not industrial policy. The next best thing, to those of a dirigiste persuasion, is to discreetly provide a dollop of protection to a few state-favoured industries. The EU has imposed tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, for example; a carbon tax will soon be levied on some goods imported into the EU. Building up European champions worthy of Europe-wide protection is the next logical step. Industry would cheer, its profits soaring as competition falls away. Consumers pay for this in the end—but long after today’s batch of politicians have disembarked. ■

Britain | Bagehot

Doctors, teachers and junior bankers of the world, unite!

The rise of middle-class consciousness

Illustration: Nate Kitch

May 28th 2025

Listen to this story

The best place to consider class consciousness in Britain today is beneath the canvas of a £283-per-night ($381) yurt at Hay Festival, a literary jamboree in Wales. Revolutionary fervour is building among those who “glamp”, as if someone had given Colonel Qaddafi a subscription to the London Review of Books.

Here in Hay-on-Wye, the men behind Led By Donkeys, an unapologetically middle-class campaign group that emerged via anti-Brexit gimmicks, can pack out an arena. Alastair Campbell, a once-disgraced spinner turned centrist-lodestar, speaks to sell-out crowds, imploring an audience in expensive walking shoes to channel their anger into a force for change. The middle classes are mad as hell and they are not going to take it any more.

Class consciousness is a simple concept. Before an oppressed class can throw off their shackles, they must know how hard they have it. Karl Marx had workers in mind when he devised it. Increasingly those who are most aggrieved in British society are not those at the bottom but those stuck in the middle. Overtaxed by the state, underpaid by their employers and overlooked by politicians, middle-class consciousness is growing.

It started with Brexit. For many in the middle class—the relatively well-off, well-educated band of voters who make up about a third of the country—this was a radicalising moment. Comfortable lives were rudely interrupted by politics. Marches against Britain’s departure from the eu represented the “id of the liberal middle classes”, argues Morgan Jones in “No Second Chances”, a forthcoming book about the campaign to undo Brexit.

What began with “the longest Waitrose queue in history”, as one joker unkindly but not unfairly dubbed the first Brexit march, did not end there. That life is tough in the middle is a feeling that goes beyond people who pay £16 to watch the lads from Led By Donkeys. Traditionally right-wing professions in Britain—such as those in the law and finance—are increasingly unhappy with their lot. The HENRYs (high-earners, not rich yet) are already revolting. Those on six-figure salaries, a small but growing part of the economy given hefty inflation and healthy wage growth, discuss ways of avoiding the grotesque cliff-edges and disincentives that kick in the second someone’s salary trips over £100,000. If no one looks out for a class, it looks after itself.

Britain’s middle class is less disparate than it seems. The banker and the bookseller have much in common. Even those in normal jobs now face high marginal-tax rates. Strangely, the Conservatives bequeathed an overly progressive tax system to Labour. Direct taxes on median earners have never been lower; those who earn even slightly above are hammered. What ails a junior banker today will haunt a teacher tomorrow. If teachers accept a proposed 4% pay rise, the salary of the median teacher will hit £51,000—shunting them into the 40% tax bracket. A tax bracket designed for the richest will soon hit a put-upon English teacher watching “The Verb”, Radio 4’s poetry show, in a tent near the Welsh border.

It should be no surprise that middle-class unions are now the most militant. Resident doctors—formerly called “junior”—were offered 5.4% by the government, but the British Medical Association has called a strike ballot. It wants almost 30%. This would be its 12th strike since 2023. Labour had tried to buy goodwill by agreeing a pay rise worth 22% in 2024. It did not work. “Bank and build” is the mantra of the middle-class Mensheviks.

Before their stonking pay rise, doctors liked to point out that some young doctors earned less than a barista in Pret A Manger. It was a delicate point. Everyone likes doctors; no one likes snobs. Yet it is a grievance that afflicts an increasing number of middle-class workers. Graduate salaries are often squished in real terms while the minimum wage cranks ever higher. Cleaners and barmen enjoy better pay thanks to the state; middle-class jobs are left at the mercy of the market. The gap between a publisher on a jolly in the Welsh countryside and the person serving them gourmet macaroni cheese is shrinking. Some do not like this. The history of class in Britain is the history of status anxiety.

Partly, middle-class consciousness is a defensive move. When Labour looks to raise money, broad-based tax rises are ruled out. That means niche attacks on the middle classes are in. Pension pots are a tempting target. The Treasury gazes longingly at ISAs, the tax-free saving accounts that are a tremendous bung to middle-class people. Middle England feels about ISAs the same way rural America feels about guns.

Being ignored and, at times, abused by politicians is a new sensation for the middle classes. For decades, their wants and needs drove political debate. As recently as 2017, entire books were written about the exclusion of the working class from British politics, arguing that the middle classes had a monopoly on political attention. Brexit inverted this deal. Now every major party (except the Liberal Democrats, who speak for England’s most prosperous corners) falls over itself to offer something to an imagined working-class voter. If Brexit taught anything, it was that voters in want of attention eventually throw a tantrum.

Aux barricades, doc