The Economist Articles for June. 3rd week : June. 15th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.06.07조회수76 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for June. 3rd week : June. 15th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Phew, it’s a girl!

The stunning decline of the preference for having boys

Millions of girls were aborted for being girls. Now parents often lean towards them

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

Without fanfare, something remarkable has happened. The noxious practice of aborting girls simply for being girls has become dramatically less common. It first became widespread in the late 1980s, as cheap ultrasound machines made it easy to determine the sex of a fetus. Parents who were desperate for a boy but did not want a large family—or, in China, were not allowed one—started routinely terminating females. Globally, among babies born in 2000, a staggering 1.6m girls were missing from the number you would expect, given the natural sex ratio at birth. This year that number is likely to be 200,000—and it is still falling.

The fading of boy preference in regions where it was strongest has been astonishingly rapid. The natural ratio is about 105 boy babies for every 100 girls; because boys are slightly more likely to die young, this leads to rough parity at reproductive age. The sex ratio at birth, once wildly skewed across Asia, has become more even. In China it fell from a peak of 117.8 boys per 100 girls in 2006 to 109.8 last year, and in India from 109.6 in 2010 to 106.8. In South Korea it is now completely back to normal, having been a shocking 115.7 in 1990.

In 2010 an Economist cover called the mass abortion of girls “gendercide”. The global decline of this scourge is a blessing. First, it implies an ebbing of the traditions that underpinned it: the stark belief that men matter more and the expectation in some cultures that a daughter will grow up to serve her husband’s family, so parents need a son to look after them in old age. Such sexist ideas have not vanished, but evidence that they are fading is welcome.

Second, it heralds an easing of the harms caused by surplus men. Sex-selective abortion doomed millions of males to lifelong bachelorhood. Many of these “bare branches”, as they are known in China, resented it intensely. And their fury was socially destabilising, since young, frustrated bachelors are more prone to violence. One study of six Asian countries found that warped sex ratios led to an increase of rape in all of them. Others linked the imbalance to a rise in violent crime in China, along with authoritarian policing to quell it, and to a heightened risk of civil strife or even war in other countries. The fading of boy preference will make much of the world safer.

In some regions, meanwhile, a new preference is emerging: for girls. It is far milder. Parents are not aborting boys for being boys. No big country yet has a noticeable surplus of girls. Rather, girl preference can be seen in other measures, such as polls and fertility patterns. Among Japanese couples who want only one child, girls are strongly preferred. Across the world, parents typically want a mix. But in America and Scandinavia couples are likelier to have more children if their early ones are male, suggesting that more keep trying for a girl than do so for a boy. When seeking to adopt, couples pay extra for a girl. When undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and other sex-selection methods in countries where it is legal to choose the sex of the embryo, women increasingly opt for daughters.

People prefer girls for all sorts of reasons. Some think they will be easier to bring up, or cherish what they see as feminine traits. In some countries they may assume that looking after elderly parents is a daughter’s job.

However, the new girl preference also reflects increasing worries about boys’ prospects. Boys have always been more likely to get into trouble: globally, 93% of jailbirds are male. In much of the world they have also fallen behind girls academically. In rich countries 54% of young women have a tertiary degree, compared with 41% of young men. Men are still over-represented at the top, in boardrooms, but also at the bottom, angrily shutting themselves in their bedrooms.

Governments are rightly concerned about boys’ problems. Because boys mature later than girls, there is a case for holding them back a year at school. More male teachers, especially at primary school, where there are hardly any, might give them role models. Better vocational training might nudge them into jobs that men have long avoided, such as nursing. Tailoring policies to help struggling boys need not mean disadvantaging girls, any more than prescribing glasses for someone with bad eyesight hurts those with 20/20 vision.

In the future, technology will offer parents more options. Some will be relatively uncontroversial: when it is possible to tweak genes to avoid horrific hereditary diseases, those who can will not hesitate to do so. But what if new technologies for sex selection become widespread? Couples undergoing fertility treatment can already choose sperm with X chromosomes or determine an embryo’s sex via genetic testing. Such techniques are expensive and rare, but will surely get cheaper.

Also, and more important, more parents who conceive children the old-fashioned way are likely to use cheap, blood-based screening in the first weeks of pregnancy to find out about genetic traits. These tests can already reveal the sex of the embryo. Some people trying for a girl may then use pill-based abortifacients to avoid having a boy. As a liberal newspaper, The Economist would prefer not to tell people what kind of family they should have. Nonetheless, it is worth pondering what the consequences might be if a new imbalance were to arise: a future generation with substantially more women than men.

The power of numbers

It would not be as bad as too many men. A surplus of single women is unlikely to become physically abusive. Indeed, you might speculate that a mostly female world would be more peaceful and better run. But if women were ever to make up a large majority, some men might exploit their stronger bargaining position in the mating market by becoming more promiscuous or reluctant to commit themselves to a relationship. For many heterosexual women, this would make dating harder. Some wanting to couple up would be unable to do so.

Celebrate the cooling of the war on baby girls, therefore, and urge on the day when it ends entirely. But do not assume that what comes next will be simple or trouble-free. ■

Leaders | Capital pains

America’s tax on foreign investors could do more damage than tariffs

Provisions in the Republican budget are a dangerous step

Illustration: Alberto Miranda

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

America needs foreign investors, and foreign investors need America. Yet clauses buried in the Republican budget bill in Congress are a threat to this crucial symbiosis. Under the obscure “Section 899”, the treasury secretary will gain the power to tax interest, dividends and rent flowing to foreigners in countries with tax systems that the law defines as “unfair”. The rate will start at 5% but could rise as high as 20%. That could mean lower returns for pension funds, governments and individual investors from the rest of the rich world. Companies with operations in America would also be caught in the net when they remit their profits. A separate clause taxes at 3.5% money sent out of the country by any non-citizen.

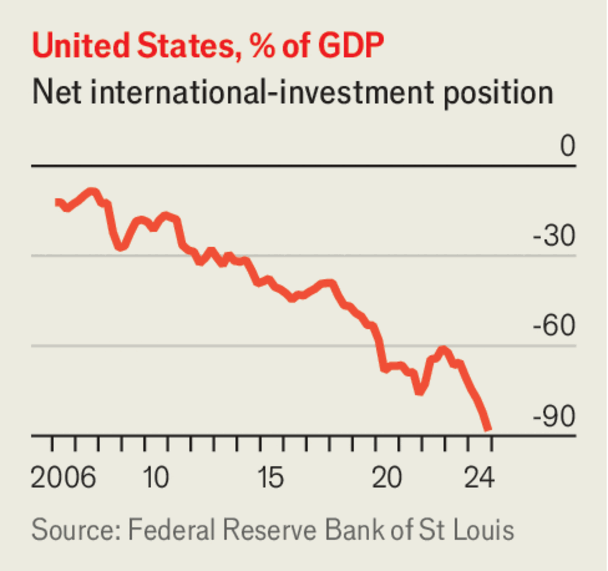

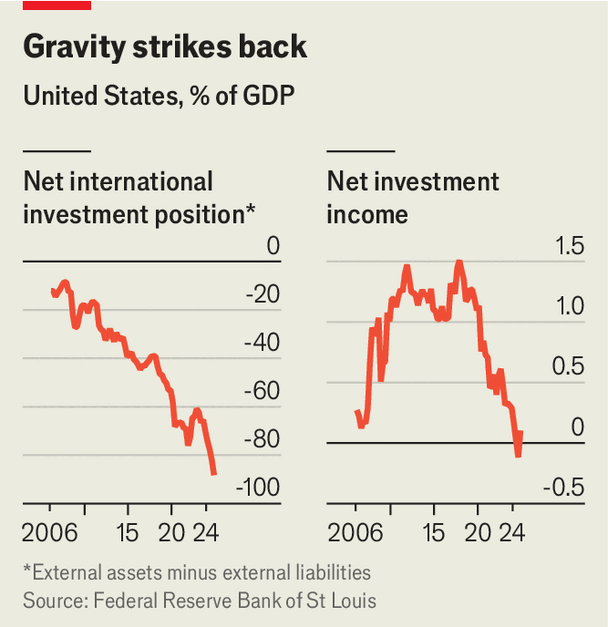

It is a worrying new front in the trade war. President Donald Trump’s tariffs have been highly disruptive, but at least America’s economy does not depend heavily on trade, which as a share of GDP is less than half the rich-world average. The same cannot be said for foreign investment, on which America is unusually reliant. Foreigners own $62trn-worth of American assets (including derivatives) compared with only $36trn owned abroad by Americans. The balance, at -90% of GDP, is by far the lowest “net international investment position” of any big, rich economy. One third of America’s government debt, amounting to $9trn, is held by foreigners.

Chart: The Economist

This is a particularly bad time for America to become less attractive to foreign investors. The budget bill, by making past unfunded tax cuts permanent, will also make annual government borrowing worth 6-7% of GDP the norm. Treasuries will probably be exempted from Section 899, but that is not yet certain. Even if they are carved out, foreign buyers might reasonably wonder if the rules could change in the future. Scaring them when there is such a big deficit to finance is reckless, especially when foreign investors have already become skittish about American assets after Mr Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcement. Moreover, the bill works against the president’s desire to have foreign companies build factories in America. Why would they, if they and their foreign staff must pay a steep price to send money home?

Capital protectionism will also badly hurt the rest of the world. Other countries could, ultimately, create their own trading arrangements and make do with restricted access to America’s goods market, which accounts for only 15% of final demand for imports. Being denied entry to Wall Street is another matter. American stocks account for about 60% of global equities by value, and the dollar is the world’s reserve asset. Even if American investments no longer produce outsize returns, foreigners would lose the benefits of diversification. The allocation of capital across the globe would be distorted, making the world economy less efficient, and therefore poorer, over time.

Optimists contend that Section 899 is a negotiating tool and that the tax on remittances is small. And didn’t other rich-world countries start the tax war by ganging up on America’s technology giants with “digital services taxes” and other rules designed to extend the reach of their tax systems across borders? The proposed law specifically targets these rules; it does not give Mr Trump a free hand.

The trouble with these arguments is that new taxes tend to expand over time regardless of their initial scope and size. There is no constituency in Congress to defend the interests of foreigners, and the legislature’s failure to avert tariffs shows how unwilling it is to challenge the president’s self-harming protectionism. The budget bill is a sign that the world could be entering an era of hostility towards foreign capital, not just foreign goods. If that day arrives, the damage will be so great that who started the fight will be irrelevant. ■

Asia | Martial law, impeachment and, finally, a new president

Lee Jae-myung is South Korea’s next president

What will the left-winger mean for the country?

Can he provide stability?Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 3rd 2025|SEOUL

Listen to this story

Six months of turmoil in South Korea are over. Lee Jae-myung of the liberal Democratic Party won a commanding victory, with 49.4% of the vote, in the snap presidential elections held on June 3rd to replace Yoon Suk Yeol, who was impeached for declaring martial law last December. Mr Lee’s triumph serves as a resounding referendum on Mr Yoon’s failed presidency: Mr Yoon’s ally, Kim Moon-soo of the conservative People Power Party, came second with just 41.2%. Mr Lee will inherit a divided society and a battered economy, as well as big challenges from abroad, in particular Donald Trump, who has threatened South Korea with tariffs and called America’s security commitments to its long-time ally into question.

Mr Lee’s win caps an improbable journey. Born into poverty, he dropped out of school as a teenager to work in factories. He retrained as a lawyer, became a labour-rights activist, and, eventually, governor of South Korea’s most populous province. In 2022 he narrowly lost the presidential elections to Mr Yoon. He survived after being stabbed in the neck last year by an extremist bent on preventing him from becoming president. Alleged election-law crimes threatened to derail his second presidential bid, but South Korean courts gave voters a chance to issue their own verdict.

In choosing Mr Lee, however, it is unclear exactly whom voters will get. Mr Lee made his name as a progressive populist. Yet in recent months he has recast himself as a sensible moderate. “Our guiding value is pragmatism,” he told The Economist in January. He pledged to boost South Korea’s benchmark stockmarket index and to make big investments in artificial intelligence. He endorsed South Korea’s alliance with America and closer co-operation with Japan. Although he has called for stabilising relations with China, he pushed back against critics who label him pro-Chinese.

However Mr Lee decides to govern, he will enjoy a commanding position, with his party controlling a majority in parliament. His first priorities will be domestic. He has called for constitutional amendments to allow presidents to serve two four-year terms instead of a single five-year term and also to make it harder to impose martial law. He also promised a fiscal stimulus package to boost the struggling economy.

But the outside world will not give the new president much respite. Mr Trump imposed steep levies on industries in which South Korean firms excel, such as cars and steel, and threatened additional 25% tariffs on goods from South Korea (which has a free-trade agreement with America). A clash also looms over whether America should maintain its current troop levels on the Korean peninsula and continue to dedicate those forces to the defence of South Korea against its nuclear-armed northern neighbour—or divert them to broader regional goals, such as deterring China.

Mr Trump may also restart negotiations with North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong Un. On that matter, he and Mr Lee, an advocate of more engagement with the North, could find common cause. But if Mr Trump cuts a deal over Mr Lee’s head, it could fuel South Korean fears of abandonment. What’s more, far-right allies of Mr Trump in America have embraced conspiracies spread by South Korea’s far-right that Mr Lee is a communist and his election was fraudulent.

Other diplomatic challenges loom. Mr Lee’s attitudes towards Japan will face an early litmus test when the two countries mark the 60th anniversary of their formal ties on June 22nd, an occasion that will bring the historical awkwardness in their relationship to the fore. In October South Korea will host an APEC summit, which will strain Mr Lee’s ability to balance between America, China and Russia.

Many South Koreans will be happy to see an end to the Yoon era. But, even so, any sense of relief will be brief. As Mr Lee himself acknowledged in his inauguration speech on June 4th, “Unfortunately, we now face a complex web of overlapping crises in every sphere.” ■

China | The Chinese economy

China is waking up from its property nightmare

An ecstatic $38m luxury-mansion auction lights up the market

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 1st 2025|SHANGHAI

Listen to this story

CHINA’S ECONOMY has been through a stress test in the past six months with the trade war shredding nerves. Tensions over tariffs are not over yet. On May 29th Scott Bessent, America’s treasury secretary, said that talks had “stalled”. President Donald Trump then exchanged accusations with China’s ministry of commerce about who had violated the agreement reached on May 12th to reduce duties. On June 4th, Mr Trump wrote on social media that President Xi Jinping was “extremely hard to make a deal with”. Yet even as the trade war staggers on, two things may be reassuring Mr Xi. One is that so far the economy has been resilient. Private-sector growth estimates for 2025 remain in the 4-5% range. The other is that one of China’s biggest economic nightmares seems to be ending: the savage property crunch.

To get a glimpse of that, consider a gated home in Shanghai’s Changning district. It has an air of traditional German architecture and a large front garden, a feature of the city’s most ritzy neighbourhoods. But what really stands out is the price. On May 27th the property sold for a stonking 270m yuan ($38m), creating a sensation in the Chinese press. At 500,000 yuan per square metre, it is one of the priciest home auctions in recent memory. That the wealthy are prepared to pony up such an exorbitant price is being interpreted as a sign that China’s huge and interminable property crisis might finally be ending.

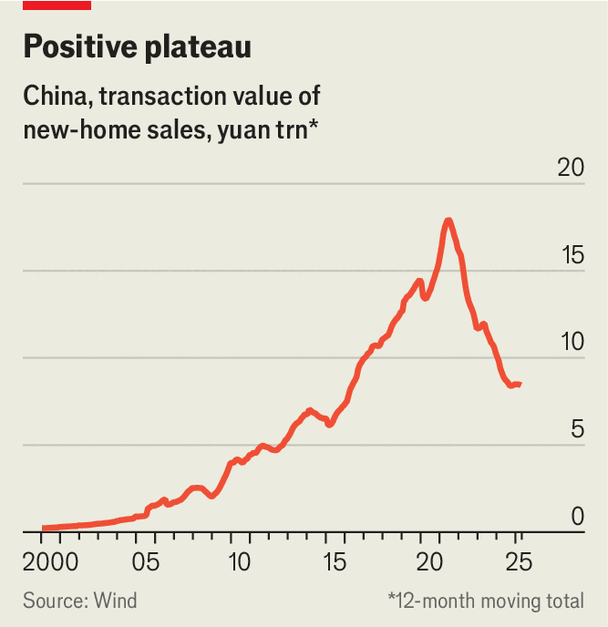

Speculation about a turnaround has been building over dinner tables, in boardrooms and at state-planning symposiums. The excitement is hardly surprising. Property, broadly defined, contributed about 25% of GDP on the eve of its crash in 2020. It now represents 15% or less, showing how the slump has been a huge drag on GDP growth. The depressive impact of falling prices on ordinary folk is hard to overstate. In 2021, 80% of household wealth was tied up in real estate; that figure has fallen to around 70%. Hundreds of developers have gone bust, leaving a tangle of unpaid bills. The dampening of confidence helps explain sluggish consumer demand.

While the market is still falling, you can make a decent case for the first time since the start of the crisis that the end is in sight. In the first four months of 2025 sales of new homes by value fell by less than 3% compared with the year before. In 2024 the decline was 17%. Transactions will continue to drop only modestly this year, reckon analysts at S&P Global, a rating agency.

Chart: The Economist

One of the biggest problems was that millions of flats were built but never sold. Last year as many as 80m stood dormant. Now in the “tier-one” cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, that problem is easing. At the end of January the inventory held by developers in those cities would have taken around twelve and a half months to shift at current sales rates, according to CRIC, a property data service. That is down from nearly 20 months in July 2024, and not far from the average of ten months in 2016-19 across the country’s 100 largest cities. In other words, the overhang is starting to look less terrifying.

Shanghai’s renaissance illustrates the trend. Transactions rose slightly each month from February to April compared with the year before, making it one of the few cities where prices have risen year on year for months in a row. It still has controls over who can buy properties and how many. But luxury homes are starting to be snapped up quickly, says Ms Fang, an estate agent. The prices of standard properties will probably continue to grow this year, she says, but the most expensive homes are increasing in value even faster.

Bottoms up

What explains the bottoming out? Partly, just the passage of time. The average housing crash takes four years to play out, according to a study by the IMF of house-price crashes from 1970 to 2003. Officials in Beijing started deflating the bubble by tightening developers’ access to credit in mid-2020 and investors started to panic about the solvency of the monster developers at the end of that year. But the government is also more determined than ever to put an end to the downturn. Local governments have been encouraged to buy unused land and excess housing with proceeds from special bonds. Some are handing out subsidies for buying homes. A plan to renovate shantytowns could create demand for 1m homes. The central bank cut interest rates in May, reducing mortgage rates for new home purchases. This has boosted property sales activity, says Guo Shan of Hutong Research, a consultancy.

There are still dangers. The trade war is a drag on confidence. Home prices across 70 cities surveyed by the National Bureau of Statistics declined by about 2% in April from a month earlier. Sales of new homes and the starting and completion of housing projects all fell month on month. Fewer cities in April notched up month-on-month price rises compared with the month before. Things are not getting much worse but they will probably not get better without more government support, says Larry Hu of Macquarie, a bank.

In Wenzhou, a manufacturing city on China’s south-eastern coast, price declines are still sharp. Locals say the trade war with America is shaking confidence. Mr Zhou, a restaurant owner, says the official data do not capture huge discounts of more than 50% on some new homes in overbuilt areas. He blames a manufacturing downturn—and Mr Trump’s trade war.

In all probability the crisis is over in big rich cities, such as Shanghai, but may last longer in smaller cities, such as Wenzhou. New-home prices in first-tier cities will be flat this year and increase by 1% next year, according to S&P. But in third-tier cities and below they will fall by 4% this year and 2% next. Small cities are full of unwanted homes. China is escaping its property nightmare. Even so, the Communist Party must ensure it is not only big-ticket mansions in Shanghai that look appealing. ■

United States | The neo-neo-con

Pete Hegseth once scared America’s allies. Now he reassures them

The defence secretary is a MAGA radical at home but a globalist abroad

Photograph: AP

Jun 5th 2025|SINGAPORE

Listen to this story

TO SOME he embodies the “revenge of the field-grade officers”, the angry mid-ranking veterans who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with loathing for the politicians and generals who sent them to fight losing wars. Pete Hegseth, a former army major and now America’s defence secretary, celebrates soldiers “with dust on their boots”. But though he may be a MAGA radical at home, there are signs that he is turning into a surprisingly conventional American globalist abroad.

Begin with the disrupter. In the name of restoring the “warrior ethos”, he has fired prominent black and female commanders, banished transgender soldiers and banned books promoting “woke” ideas. He has also been obsessed with leaks, sacking staff suspected of disloyalty. As a “recovering neocon”, he shocked European allies in February by appearing to forsake Ukraine and NATO. “President Trump will not allow anyone to turn Uncle Sam into Uncle Sucker,” he warned.

Yet on May 31st he presented an altogether more reassuring and familiar American persona at the Shangri-La Dialogue, an annual Asian security conference in Singapore organised by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a British think-tank. Mr Hegseth described allies not as a burden, but as “force multipliers”. As he put it, “America First certainly does not mean America alone.”

Mr Hegseth told Asian allies that America had their backs: “We are here to stay.” And rather than berate Europeans, he held them up as models for Asia to emulate as they rushed to re-arm. He warned that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan “could be imminent” and implied any assault would lead to war with America. “We will not be pushed out of this critical region, and we will not let our allies and partners be subordinated and intimidated,” he insisted.

For all his bellicose tone—China warned him not to “play with fire”—many in the audience welcomed his comments as a return to normality. Mr Trump, after all, has accused Taiwan of “stealing” America’s chip industry. Even such erstwhile defenders of the island as Elbridge Colby, recently confirmed as the Pentagon’s under-secretary for policy, seemed to want America to stand back when he said a Chinese takeover of Taiwan would not be an “existential” threat. In Mr Hegseth’s telling, it “would result in devastating consequences for the Indo-Pacific and the world”.

Foreign interlocutors who meet him are pleasantly surprised. “He is not a caricature. He listens,” says one. The forthcoming defence budget, and decisions about force deployments globally, will reveal much about his philosophy. He has privately assured NATO that any drawdown in Europe will be done “responsibly”. South Korea worries about American troop withdrawals, too.

How to explain Mr Hegseth’s duality as a culture warrior at home and apparent upholder of the status quo overseas? He has not given up being the grunts’ champion. Before dawn Mr Hegseth set out for physical training with the troops, doing jumping jacks and push-ups with the crew of the USS Dewey, a guided-missile destroyer docked at the island.

Those who know him say it comes down to him being a “half-trained Jedi”. He has fierce views about masculinity and loyalty to the “trigger-pullers”. But he is out of his depth in one of the world’s most complex bureaucracies, which explains the managerial chaos. Although a Princeton graduate, he lacks fully formed views on geopolitics, never having gone to war college or worked at a think-tank or in Congress. (After his service, Mr Hegseth ran veterans’ organisations and became a Fox TV host). Thus, some surmise, on matters of strategy he may be deferring to the very generals he claims to despise.

Many abroad, and even some critics at home, see signs that Mr Hegseth is learning fast. His former associates, though, worry he is being tempted away from the MAGA faith. The question for all is whether the new-look Mr Hegseth speaks for Mr Trump, or will be disowned by him. ■

The Americas | Still divided

Slums, swimming pools and Latin America’s inequality

Its tax and welfare systems are shockingly bad at reducing inequality

Photograph: Johnny Miller

Jun 5th 2025|MONTEVIDEO

Listen to this story

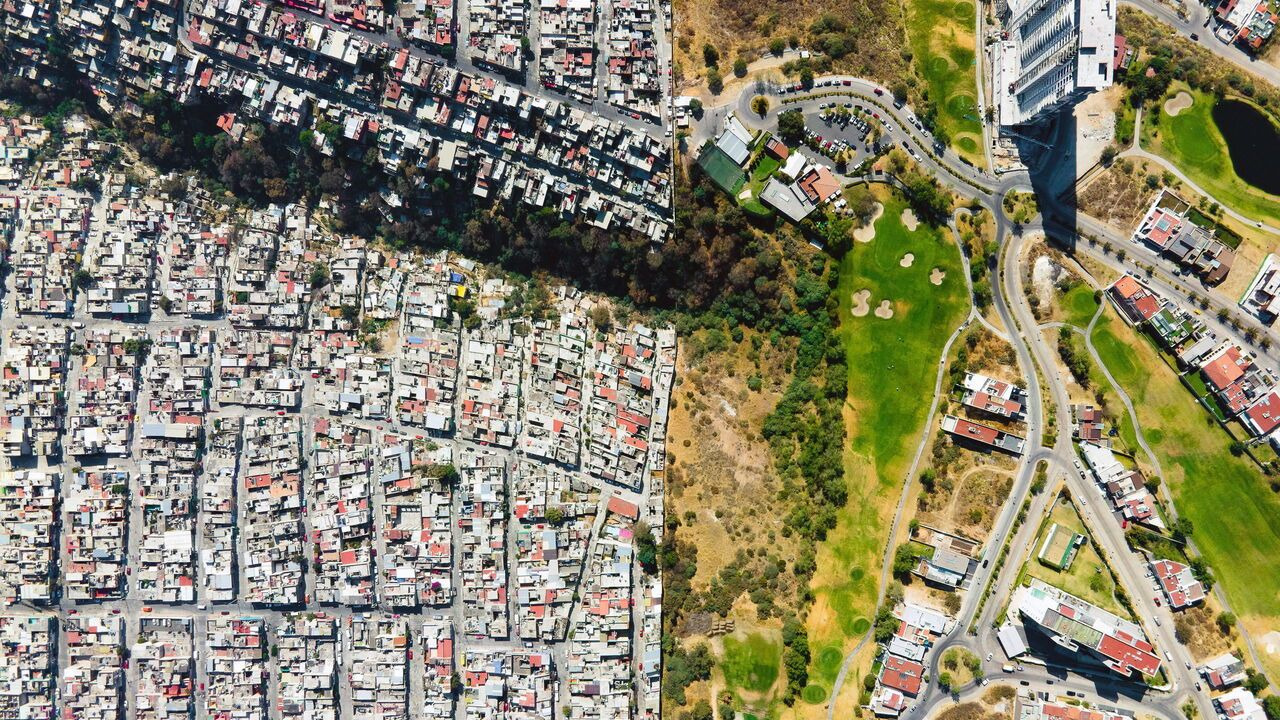

TO SEE REALITY in the Buenos Aires suburb of San Isidro, consider the drone’s-eye view (pictured). A razor-straight line divides lush gardens and smooth clay tennis courts from a mess of corrugated iron roofs in one of the city’s “villas miserias”. Santa Fe in Mexico City looks similar, the jewel-green of the golf club hemmed in by endless concrete boxes of the city’s strugglers. Rio de Janeiro’s favela of Rocinha sees makeshift dwellings spiral down the mountain, all but crashing into the turquoise swimming pools below.

Such visceral inequality is the defining feature of Latin America’s economies. The disparities in the region are rivalled only by those in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet because inequality is usually lower in richer places, and Latin America’s GDP per person four times that in Africa, its inequality is extraordinary. Some countries such as Colombia and Guatemala are extremely unequal, others such as Uruguay less so. Yet there are no exceptions. The World Bank does not class a single country in the region as “low-inequality”.

This shapes Latin America in countless ways beyond bird’s-eye photography: physically, through the proliferation of high fences and security cameras; politically, in populism and leftward lurches; and economically, through low social mobility, large informal economies and weak internal demand. The Economist will publish several articles this year exploring this dynamic. To start, it helps to understand why Latin America made good progress to reduce inequality in the 2000s, and why that progress has slowed.

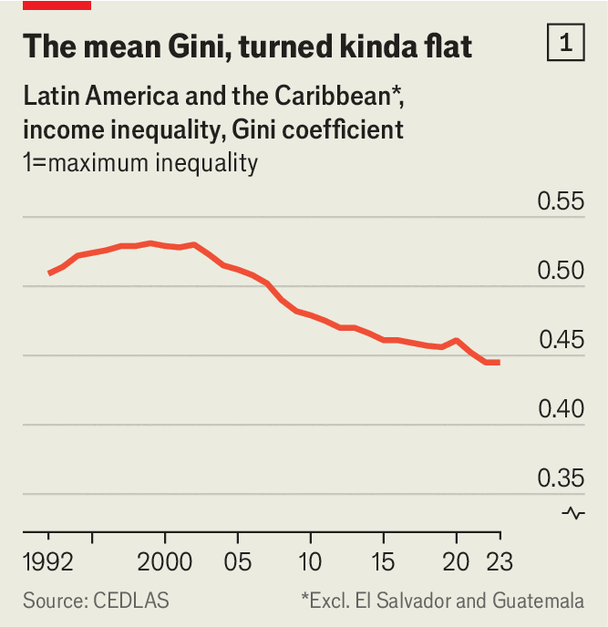

Chart: The Economist

The most common way to measure inequality is the Gini coefficient. This ranks a country’s income inequality between zero and one. Zero means everyone in the country gets the same income; one means a single person receives everything. Other kinds of inequality matter, too, but none transcend income. Unequal access to good education and health care are both outcomes of income inequality as well as being important causes of it.

The broad trend in Latin America is clear: inequality rose through the 1990s, peaked in about 2002 and then began to fall. Around 2014 the decline began to slow, and recently it has flatlined (see chart 1). There are exceptions—the Gini coefficient is still falling, though more slowly, in Peru and has been rising in Colombia—but the overall trend is plain.

Two things drove the decline between 2000 and 2010. One was government handouts. Conditional cash-transfer programmes such as Bolsa Família in Brazil gave money to poor families if they sent their children to school and for health check-ups. Across the region, transfer programmes of all kinds accounted for about 20% of the fall in inequality on average. A second factor mattered much more: strong growth in wages for the poor. This accounted for over half of the fall. The backdrop to this was a long period of robust economic growth, helped along by a commodities boom. The lesson, says Ana María Ibáñez of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), is that “If we want to reduce inequality, we need to grow.”

There is a series of smaller problems, too. One is the heavy influence of family background. A paper by Paolo Brunori of the University of Florence and co-authors finds that more than half of the current generation’s inequality is in effect inherited, largely as a result of their parents’ level of education and type of jobs.

Photograph: Johnny Miller

Photograph: Johnny Miller

To see how this works, consider the cycle a family background can set off. As Ms Ibáñez and co-authors explain, toddlers of richer parents often get better food and more attention, so develop more skills. This helps them take advantage of the better (often private) schools they attend, which in turn push them on to university where attendance strongly boosts earnings in Latin America, in large part by helping students get formal jobs in big companies. Children born into poorer families tend to go to worse schools, often don’t make it to university and end up working in Latin America’s large, less productive informal sector. And so the cycle revolves.

When inequality was falling, strong economic growth boosted poor Latin Americans’ wages, helping break the cycle. Yet growth has stalled horribly. Real income per person in Latin America and the Caribbean increased by a dismal 4% in total between 2014 and 2023. In South Asia, by contrast, it increased by 46%.

Governments have turned to other less effective remedies. A popular choice is to up the minimum wage. Mexico’s last president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, doubled it in real terms during his six years in office. Claudia Sheinbaum, his successor, has promised annual increases of 12%. This has helped reduce poverty and inequality in Mexico, in part because the minimum wage was very low when Mr López Obrador took office. But there are limits. If productivity does not also increase, a rising minimum wage tends to increase informal jobs, dragging people back into the inequality feedback loop.

Chart: The Economist

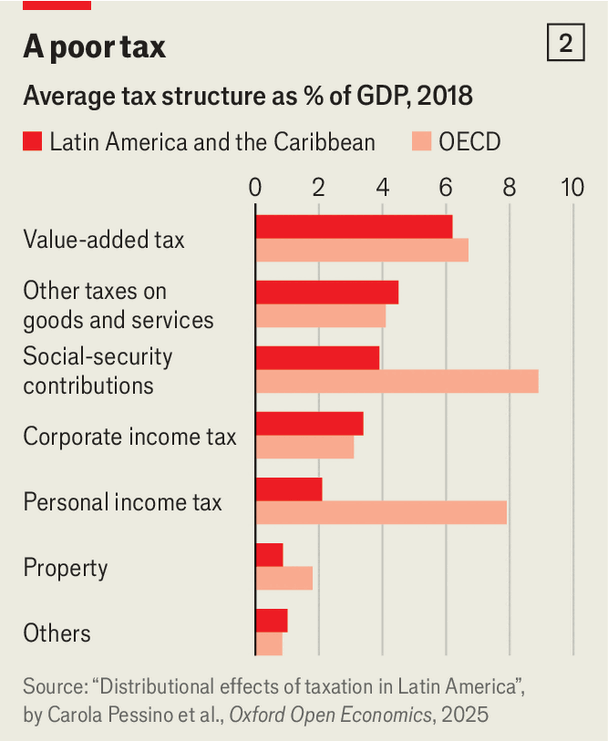

Governments also hope redistribution can deal with inequality. The immediate problem with this is that soft growth means thin government revenues, so less money to redistribute. Still, Latin American tax and welfare systems could do far better. When the region’s income inequality is measured before taxes and redistribution, it is only slightly higher than in rich countries. But whereas taxes and transfers reduce the Gini coefficient by almost 40% in rich countries, in Latin America they only reduce it by about 5%. Shockingly, in about half the region this translates into an increase in poverty.

The biggest problem is taxation. Across the OECD, a club of mainly rich countries, personal income taxes, which are usually progressive, are worth 8% of GDP. In Latin America they are worth just 2%. Instead, the region relies more on indirect taxes, such as VAT on goods and services (see chart 2). These are often regressive, as the rich and poor pay the same rate but the poor consume a larger portion of their income, so are hit harder.

Many welfare programmes are also riddled with problems. An IDB study of transfer programmes in 17 countries found that targeting is wayward. Only about half of people living in poverty benefit, while about 40% of those not in poverty get at least one kind of transfer. The amounts being transferred are often too small.

The circle is still vicious

Fixing this could put a big dent in inequality. But even as anger about disparities dominates election campaigns and sometimes explodes in the streets, as it did during violent protests in Chile in 2019, there is little progress. Though cross about the status quo, voters are not keen to change tax and welfare systems either. A study by Matias Busso of the IDB and co-authors surveyed eight countries and found that, while respondents are unhappy about inequality and support redistribution in theory, they are reluctant to pay extra taxes to fund it. One reason is that many mistrust the state and ruling elites.

All this adds up to a daunting challenge. Sustained growth, last seen over a decade ago, would provide the sharpest relief. Political reforms that build trust in government and allow for improvements to taxation and welfare would help. Both would be ideal. Neither seems likely. ■

Middle East & Africa | The Israeli far right

Israel “won’t commit suicide”, says the government’s ideologue

In an interview Bezalel Smotrich is uncompromising about the war in Gaza

Photograph: Tomer Appelbaum for The Economist

Jun 4th 2025|Tel Aviv

Listen to this story

ACCORDING TO THE unofficial ideologue of Israel’s government, its war in Gaza is going well. The new plan to distribute aid to civilians through hubs controlled by Israel is working, says Bezalel Smotrich, the finance minister. It is a “gamechanger” in the fight against Hamas. He has repeatedly opposed ceasefires, by threatening to leave the coalition of which he is a key member.

Now he has a different emphasis. Providing the government seeks to end the war with the defeat of Hamas, he will stay (though there is now a chance that the government may be brought down imminently by its ultra-Orthodox partners, who are frustrated that a controversial law exempting religious students from military service has not been passed by the coalition).

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

Since the atrocities of October 7th 2023 Mr Smotrich’s words have been among the most incendiary from Israeli politicians. He has predicted Gaza will be “totally destroyed”. He has been accused of justifying starvation as a tactic in war, saying last year that aid should flow into Gaza only if the hostages are returned.

In an interview with The Economist on June 3rd he sought to present himself as a sober-minded, constructive member of the government. But there is no disguising that his vision is extreme and messianic. The war has given him and those who share his views an opening, and they have seized it.

The day after we spoke to Mr Smotrich, Israel closed its new aid centres in Gaza temporarily. The Israel Defence Forces said that the roads leading to the hubs will be considered “combat zones”. That decision came after days of chaos around the distribution centres in which dozens of Gazans were shot and killed on their way to collect food.

Under the new system, aid is brought in convoys protected by Israel and distributed by American mercenaries, rather than by the UN. Gazans must travel to any of four distribution hubs in the ruined enclave to pick up family-sized boxes on a weekly basis. Mr Smotrich says this method of delivering aid is important for Israel to win the war.

No time for critics

He says he is bewildered by criticism from international aid organisations and European governments. Critics say the aid scheme is insufficient to feed Gaza’s hungry people and a cover for plans to corral Palestinians into a small area while depopulating most of Gaza. It is the best way to shorten the war and alleviate suffering, counters the finance minister.

He claims he has always favoured letting aid into Gaza (though less than two months ago he said Israel should not allow “even a grain of wheat” to enter the strip); he simply opposed the way in which it was being done. He said it kept Gazans reliant on Hamas and allowed the group to profit from it. Breaking that link is crucial to Israel’s victory, he explains.

Stick to the plan and the war can be over in a matter of months, he says, but Hamas must surrender, disarm and send its leaders into exile. Anything less will leave the group in a position to attack again in a few years. Once Hamas is gone, Gaza can be “rehabilitated”, he says. But the tunnels used by Hamas will still need to be dismantled; so far Israel has destroyed only a quarter, he claims. If Hamas does not leave, and the fighting continues, further devastation for Gaza seems inevitable.

Mr Smotrich acknowledges no wrongdoing on Israel’s part. More than 50,000 Palestinians have been killed but he says the ground assault has been “gentle” and the army has been “using tweezers” in its targeting. He says half of those killed are combatants (Israeli officers say it is closer to a third; there are no verified figures distinguishing between combatant and civilian fatalities). He blames Hamas, as terrorists who hide behind civilians, for the death toll.

He has no thought of Israel leaving Gaza. He has called for the building of Israeli settlements throughout a Gaza depopulated of Palestinians: “Where there are settlements and the army, there’s security; where there aren’t settlements and army, there is no security.” He denies Gazans would be forced to leave but concedes that the war has rendered Gaza uninhabitable and that those who want to should be “allowed” to emigrate. The European countries that are threatening to impose sanctions on Israel and “preach” about solving the conflict should welcome Palestinians, he suggests.

Photograph: Tomer Appelbaum for The Economist

His longer-term vision for the Palestinians involves them either abandoning the land that Israel occupies or living with limited rights under its control. Mr Smotrich grew up in settlements in the West Bank (which he insists on calling Judea and Samaria, its biblical name). He still lives in one and rejects any possibility of Palestinian statehood there. He says allowing this would create the “existential” threat of an attack on Israel “20 times worse” than the one that occurred on October 7th.

When it comes to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, “there is a big difference between individual rights and national rights”. This means that most Palestinians, apart from those who currently live in Israel, will remain without full citizenship or voting rights. “If there is a process of deradicalisation, if there is a generation that accepts that Israel is a Jewish and democratic state, that wants to live with us in a pact…I don’t mind giving them the vote,” he suggests. But “I can’t let them destroy me through democracy after they failed to do it by terror.”

This seems to rule out normalising relations with Saudi Arabia. The kingdom has said it will not establish ties with Israel without a process towards a Palestinian state. A Saudi deal is a prize but “we won’t commit suicide for it”, says Mr Smotrich. He insists that “in closed rooms” Israel is hearing other things from its Arab counterparts: “All our neighbours are looking at Gaza and waiting to see what we do.” He is confident that a bright future of regional integration awaits.

Israelis may welcome the finance minister’s talk of peace with their neighbours but his vision for their country raises alarms. Some fear that, given the opportunity, he would turn Israel into a theocracy. Asked about his call in 2019 for restoring “the laws of the Torah” as in the biblical days of King David, he says: “There is no contradiction between halachic [religious] law and democracy.”

Mr Smotrich is in many ways a minority figure. Were elections to be held, surveys indicate his ultra-nationalist party would struggle to cross the electoral threshold of 3.25% of the vote. At best, it would win a handful of seats. After Binyamin Netanyahu returned as prime minister in 2022, he insisted that the far right “are joining me, I’m not joining them”.

And yet this is the hardliners’ government. Under their pressure it has tried to tamper with Israel’s legal system and has lavishly funded religious programmes and expanded settlements in the West Bank, with a stated aim to annex the territory. If Mr Smotrich left the coalition, his fellow radical, Itamar Ben-Gvir, would follow suit, denying Mr Netanyahu his majority. But Mr Smotrich has stayed because, for him, the war has proved an unparalleled opportunity to fulfil his long-held vision. ■

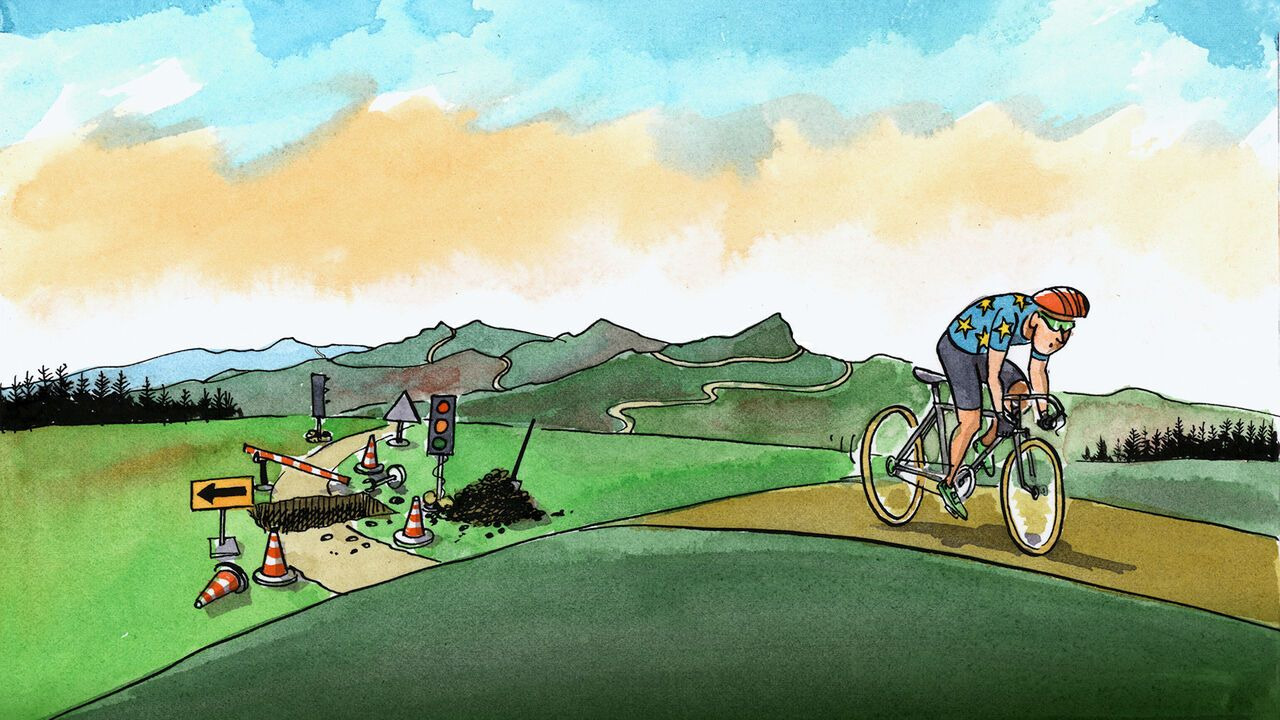

Europe | Charlemagne

The constitution that never was still haunts Europe 20 years on

The stumble of 2005 resulted in a better EU

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

Europe is famed for its zippy German cars, French high-speed trains and sleek Italian motorboats. But for decades the contraption most often favoured to describe the workings of the European Union was the humble bicycle. Federalists painted the EU as an inherently unstable machine whose only chance to avoid a crash was to keep moving forward. The self-serving analogy justified furious pedalling by those who dreamed of “ever-closer union” lest the whole thing keel over. By the early 2000s the argument that more integration was always better had made its way. What had once been a modest pact between six countries to regulate coal and steel production had morphed into a political union of 25 (later up to 28), with a shared currency, no internal borders and the rights for citizens from Lisbon to Lapland to settle down where they saw fit. Who could tell where a few more decades of such freewheeling towards continental convergence would lead?

In an anniversary precisely nobody in Brussels is marking, the theory of more-integration-or-bust got a nasty puncture 20 years ago this month. A “constitutional treaty” dreamt up as the next big step in EU integration was voted down by French voters on May 29th 2005, by a 55-45% margin. On June 1st Dutch voters rejected it by an even wider one. Those convinced the EU had only one gear—en avant, toute!—fretted that the defeat might result in gradual disintegration; war pitting Europeans against their fellow Europeans would be only a matter of time. That was always hyperbole; it also proved to be entirely wrong. After 2005 the EU shelved its grandiose plans for a more technocratic life—and has never been more popular with citizens as a result. Bitter as it seemed at the time, defeat at the polls set the union on a better track.

These days the idea of a constitution is remembered as a curio of European history. The EU and its forebears had, since its inception in 1957, been ruled by intergovernmental treaties, in legal terms a souped-up regional version of the UN. By the early 2000s a new text was undoubtedly needed to streamline the club’s workings after a period of rapid expansion. Enlargement with ten new countries in 2004, most of them in central Europe, threatened to gum up the machine’s gears if not revised (a lot of business that had required EU national governments to agree unanimously was to be replaced by qualified-majority votes). But the second purpose, just as important to some, was to endow the EU with the regalia of a nation state—hence the constitution bit.

The document had been crafted by a “convention” chaired by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, haughty even by the standards of former French presidents. The parallels with the birth of America were intentional. The preamble of the Euro-constitution invoked the “will of the citizens” as a justification for these new arrangements between them (never mind that the citizens knew little about this supposed will of theirs). Symbols meant to foster citizenly love for the EU oozed from the text. It already had a directly elected parliament; now the union was to have its own official flag, anthem, foreign minister and even a dedicated holiday.

For all the symbolism it contained, the constitution was no federalist power-grab. Despite being denounced as a “blueprint for tyranny” by Britain’s Daily Mail, a fount of Euro-outrage, the text disappointed those who wanted the EU to have its own taxation powers, for example. (The Economist felt the text was confusing and recommended filing it in the nearest rubbish bin.) The French non and Dutch nee were not enough to send the machine entirely off course. By 2009 much of the 450 pages of the constitution—brevity was not one of Giscard’s strong points—had been recycled into the Lisbon treaty, which shoehorned most of its provisions into a whopper amendment of two EU treaties already in force. The union did deepen somewhat as a result, for example giving its parliament a bit more power. But anything that smacked of symbolism was left on the cutting-room floor. The post of foreign minister was replaced with the odd-sounding “High Representative/Vice-President” for foreign affairs.

Worse, the failed constitutional gambit allowed a new brand of Euroscepticism to take root. The urban and upper classes had backed the EU in the French and Dutch referendums. Rural and working-class types had not. Populists decried the adoption of most of the constitution’s clauses by the back door; Marine Le Pen in France dubbed it “the worst betrayal since the second world war”. Brussels has never shaken off the idea that it is a project of the elites.

We the People are not keen on this sort of thing

Voters in Ireland and Denmark had previously rejected EU treaties—before being made to vote again. Having two of its six founding members reject the constitution was a different matter. The votes “brought the process of European integration to an abrupt and durable halt”, says Jean-Claude Piris, who served for decades as the EU’s top lawyer and helped draft the treaties. It made the prospect of future treaties too daunting to even contemplate. The EU retreated into intergovernmental technocracy, where it remains to this day.

This is dispiriting to some. It need not be. Yes, the EU is still a distant beast to citizens. Over a third of Europeans admit they have little idea how it actually works. But that has not stopped the union from being effective: 74% of Europeans think it serves their own country well, a record high. The EU has even integrated more, on necessary occasions, such as when governments in 2020 agreed to jointly issued bonds to fund a post-pandemic recovery stimulus. A union of states, with independent institutions on hand to push common interests forward in areas where Europe needs to act as one, turns out to be a fine idea. It had never needed to be more than that. ■

International | The Telegram

To earn American help, allies are told to elect nationalists

MAGA-world flirts with forces that once tore Europe apart

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Jun 3rd 2025

Listen to this story

ACORE SKILL in MAGA diplomacy is the making of offers that cannot be refused. Karol Nawrocki “needs to be the next president of Poland. Do you understand me?” Kristi Noem, America’s Homeland Security Secretary, urged voters in Poland on May 27th. Ms Noem was addressing a rally in Jasionka, a logistics hub near the frontier with Ukraine, days before a presidential election pitting Mr Nawrocki, a nationalist historian, against the progressive, pro-European mayor of Warsaw.

Then Ms Noem added a hint of menace, seeming to imply that Poles should choose the right head of state if they want American troops to stay in their country. To many Poles, that garrison is a flesh-and-blood guarantee of American support. If Poles elect a leader who will work with President Donald Trump, they will have a strong ally against “enemies that do not share your values”, Ms Noem told the crowd. With the right leader, “you will have strong borders and protect your communities” and “you will continue to have a US presence here, a military presence”, she went on.

Mr Nawrocki pulled off a narrow victory on June 1st. In a message of congratulations, America’s secretary of state, Marco Rubio, declared: “The Polish people have spoken and support a stronger military and securing their borders.” It will never be known how many votes were swung by Ms Noem’s intervention. Still, her election-eve visit is evidence of a revolution in America’s relations with Europe. The notion that America sees a vital interest in Europe’s collective security is being replaced by something more grudging and conditional. This selective American offer builds on familiar complaints, from Democratic and Republican presidents, that European members of the NATO alliance need to spend more on their own defence. But Trumpworld’s impatience with Europe goes beyond grumbles about free-riding. Take Ms Noem and Mr Rubio at face value, and foreigners who hope to be defended by America would do well to show fealty to Trumpism.

Europe’s leaders face a dilemma. Though they are desperate to maintain defence ties with America, Mr Trump is not focused on the same threats as they are. His aides are obsessed with borders. He sounds eager to cut deals with President Vladimir Putin, though it is fear of Russia that explains why Poles want an American garrison. As for the European Union, Mr Trump treats it as a hostile power, which he says was created to “screw” his country.

Mr Trump and aides condemn Europe’s approach to transatlantic trade, and to the regulation and taxation of businesses, notably American technology firms. Its leaders are called hysterical about climate change. The EU is deemed disastrously open to immigration, and a bully for asking governments to share the burden of hosting asylum-seekers who arrive at its external frontiers (a charge of bullying that Mr Nawrocki made to Polish voters).

Some criticisms are worth pondering. Addressing the Munich Security Conference in February, the vice-president, J.D. Vance, was right to question heavy-handed European controls on free speech and the bans that some countries impose on political parties with broad support. But Mr Vance was point-scoring when he called that “threat from within” more dangerous than Russia.

It is now painfully clear that Europe is caught up in America’s domestic, partisan politics. Asked to explain that Munich speech, a well-connected Washington conservative reports that, as a “culture-war Catholic”, Mr Vance felt personally offended when secular-minded “chattering-class Europeans” scolded America’s Supreme Court for ruling against abortion rights. To Trumpworld, the EU is a haven for globalist, woke elites, to be brought to heel like Harvard University or the State Department.

Trumpian loathing for Europe goes beyond present-day culture wars, though. Mr Trump’s real fight is with the American presidents who defined post-war transatlantic relations. Closer European co-operation was not a plot to “screw” America. Indeed, post-war American governments urged Europeans to seek economic and political union, invoking the example of America’s founding fathers. Only a prosperous continent could avoid the “despair” that led people to seek out fascism and communism, Harry Truman said in 1947, as he urged Congress to approve the Marshall Plan to fund Europe’s reconstruction. The 33rd president praised post-war European leaders for shunning “narrow nationalism” and agreeing to “the reduction of trade barriers, the removal of obstacles to the free movement of persons within Europe, and a joint effort to use their common resources to the best advantage”.

Thank your predecessors

Today’s German laws to ban extremist parties were drafted at the urging of post-war American lawyers and diplomats, anxious about Nazism’s return. Dwight Eisenhower, the former general turned 34th president, said European unity was needed to demonstrate to America that its provision of aid was worthwhile. To leaders in Washington, European integration was the answer to the “German problem”: how to let Germany re-emerge as an economic giant without terrifying its neighbours and risking another war.

For all modern Europe’s flaws, Truman, Marshall, Eisenhower and their peers succeeded. In Mr Nawrocki, Poland has just elected a nationalist fire-breather as president who scorns the EU and says he will seek vast reparations from Germany for wartime crimes. Yet the risks of war between Poland and Germany, or between any EU countries, remain approximately zero. That miracle of peace was not known in any earlier century. It allows Ms Noem and her ilk to use America’s role as a security guarantor for leverage and to play divide and rule with EU unity, with no risk of conflict within Europe’s borders. Mr Trump and his team may despise the visionaries who rebuilt Europe after 1945. But they are free-riders on their work. ■

Business | Schumpeter

AI agents are turning Salesforce and SAP into rivals

Artificial intelligence is blurring the distinction between front office and back office

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

ENTERPRISE SOFTWARE is an unlikely source of hubbub. Bringing up CRM or ERP in conversation has usually been a reliable way to be left alone. But not these days, especially if you are chatting to a tech investor. Mention the acronyms—for customer-relationship management, which automates front-office tasks like dealing with clients, and enterprise resource planning, which does the same for back-office processes such as managing a firm’s finances or supply chains—and you will set pulses racing.

Between June and early December 2024 Salesforce, the 26-year-old global CRM giant, created more than $120bn in shareholder value, lifting its market capitalisation to a record $352bn. In the past 12 months SAP, a German tech titan which more or less invented ERP in the 1970s, has generated more. It is Europe’s most valuable company, worth $380bn, likewise an all-time high. Both enterprise champions rank among the world’s top ten software companies by value. Maybe not so dull, after all?

The source of the excitement is another, much sexier acronym: AI. Builders of clever artificial-intelligence models may get all the attention; this week Elon Musk’s xAI hogged the headlines when it was reported that the startup was launching a $300m share sale that would value it at $113bn. But if the technology is to be as revolutionary as boosters claim, it will in the first instance be because businesses use it to radically improve productivity. And as anyone who has tried—and probably failed—to replace corporate computer systems will tell you, they are likely to do so with the assistance of their current IT vendors.

Salesforce and SAP each believes it will be the one ushering its clients into the AI age. The trouble is that many of those clients use both firms’ products. Perhaps nine in ten Fortune 500 firms run Salesforce software. The same share relies on SAP.

This did not matter when the duo focused on their respective bread and butter. A client would run Salesforce’s second-to-none CRM in the front office and SAP’s first-rate ERP in the back. Amazon and Walmart, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, BMW and Toyota: pick a household name and the odds are it does just that.

A big reason for SAP and Salesforce to slather a thick layer of AI on top of their existing offering, though, is to give customers a way to uncurdle their data, analyse it and, with the help of semi-autonomous AI agents interacting with one another on behalf of their human managers, act on it. In this newly blended world, the lines between front and back office are fudged. “It’s one user experience,” sums up Irfan Khan, SAP’s data-and-analytics chief.

Controlling the user interface for this “agentic” AI experience promises fat profits. It also creates a head-to-head rivalry between the two enterprise masterchefs. For their AI recipes look alike.

Step one: expand your range of products. SAP has improved its front-office chops by buying CRM firms (like CallidusCloud) and marketing platforms (such as Emarsys). Though Salesforce has not gone full-ERP, it has a 16-year-old partnership with Certinia, whose financial-management system sits exclusively atop its platform. It has bought firms like ClickSoftware, which helps businesses manage their service workforce. On June 2nd it hired the team behind MoonHub, a recruitment-and-HR startup. Clients, spared from switching between providers for every specialist function, love it. So do SAP and Salesforce, since it amasses more client data, AI’s great leavener, in their own systems.

Step two: piggyback on the “hyperscalers”. This allows clients to choose between the cloud giants, including, in China, Alibaba and Tencent (and, in Salesforce’s case, excluding Microsoft, with which its co-founder and boss, Marc Benioff, has a long-running feud). It saves SAP and Salesforce from splurging on what each sees as infrastructure destined for “commoditisation”. Oracle, the giant of corporate-database management which has taken the opposite approach, has seen its quarterly capital budget explode from $400m in 2020 to nearly $6bn in its latest quarter; SAP and Salesforce spend $300m-400m a quarter between them.

Step three: whip up the AI layer. In February SAP teamed up with Databricks, a $60bn AI startup, to help clients make sense of their information, including that stored outside SAP systems, and deploy SAP’s Joule AI agents across their operations. On May 27th Salesforce said it would pay $8bn for Informatica, which designs tools to integrate and crunch corporate data. This will make its own Agentforce easier for clients to use beyond the front office.

Right now investors prefer what SAP is serving up. Its systems cover a wider range of functions and thus contain more data. This data is also notoriously hard for non-SAP systems to extract. As annoying as this may be for clients, it gives them an incentive to look from inside the SAP platform out rather than the other way round. SAP’s share price has risen by 12% in the past six months.

Meanwhile, Salesforce’s has collapsed like a bad soufflé. It is down by nearly 30% since its peak in early December. Although its sales passed those of SAP in 2023, growth is slowing while SAP’s accelerates. Analysts wonder if Agentforce, the launch of which fuelled last year’s rally, can make real money. They also fear a return to profligate dealmaking that culminated with the $28bn purchase in 2021 of Slack, a corporate-messaging platform.

Too many cooks

Investors could yet sour on SAP just as they have on Salesforce. Gartner, a research firm, reckons that between 2020 and 2024 rivals like Workday cut its share of the ERP business from 21% to 14%. For all its front-office efforts, its CRM sales declined around that time, even as Salesforce preserved its 20% slice of a growing market. Microsoft, which has its own cloud, its own cutting-edge AI and plenty of business clients, is elbowing its way into ERP, as well as CRM. The enterprise-AI food fight is just beginning. ■

Business | A degree of uncertainty

Which universities will be hit hardest by Trump’s war on foreign students?

It’s not the Ivy League

Donald Trump would prefer a MAGA hatPhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 3rd 2025

Listen to this story

If college presidents were hoping Donald Trump would tire of lambasting America’s universities, the latest tirades against international students have left them freshly agog. On June 4th Mr Trump escalated his attacks against Harvard, issuing an order suspending the university from a student-visa programme, which would stop foreigners from attending. Of wider impact is the government’s decision to pause scheduling new visa interviews for foreign students, no matter where they aim to study. Beyond the damage this is doing to America’s reputation, and its prowess in research, the tumult has bean-counters across the country’s higher-education system wringing their hands.

Many American colleges and universities were facing financial problems long before Mr Trump’s return to the White House. Americans have soured on higher education, after years in which participation grew fast. The share of high-school leavers going straight to college fell from around 70% in 2016 to 62% in 2022. In December Moody’s, a rating agency, said a third of private universities and a fifth of public ones were operating in the red.

Looming demographic change will bring more trouble. The total number of high-school graduates in America may fall by around 6% by 2030 and 13% by 2041, according to one estimate. The impact will vary widely by region: in some north-eastern and mid-western states (which for historical reasons have a surfeit of universities) the decline could be as high as a third.

Foreign students are not an antidote, but they are helping offset some pain. The million or so foreigners studying in America are roughly double the number in 2000. They pay far higher fees than locals for undergraduate courses—in some public universities as much as three times the rate, says William Brustein, who has led international strategy at several of them. Over half the foreigners are postgraduates; these courses tend to bring outsize profits.

Though America has more foreign students than any other country, it would seem to have room for more: they make up only about 6% of those in higher education, compared with over 25% in each of its main competitors—Britain, Australia and Canada. For now, alas, growth is the last thing anyone expects. The risk is both that the number of foreigners who turn up this autumn will fall sharply, and of a longer-lasting depression caused by future applicants turning to countries that seem more welcoming than America.

The big question is who might suffer the most if there is a bust. Ultra-elite institutions may look exposed: around 28% of Harvard’s students and a whopping 40% at Columbia come from abroad. But these institutions have many ways to balance the books: last year tuition fees (both domestic and foreign) and payments for room and board made up only about 20% of Harvard’s total income, compared with over 80% at the least prestigious private universities. Demand for spots at the highest-ranking universities is rarely affected by a slowdown and their home-grown students could pay more.

The trouble might be greater for second- and third-tier institutions, where foreign students are not quite so numerous but are often more important to the bottom line. For many years public universities ramped up foreign enrollment to make up for declining funding from the state where they are located. The best of these institutions were able to boost revenues by attracting high-paying Americans from out of state, whereas the rest had no choice but to pay agents and marketers to bring in overseas students.

A pronounced slowdown in overseas arrivals could damage institutions, even those that have never enrolled a single foreigner. If highly regarded universities adapt by enrolling more local students, that will make it harder for institutions with lesser reputations to attract them, and thus to pay their bills. In Britain, changes to visa rules have recently brought sharp falls in arrivals of foreign students. Last year about 40% of universities predicted operating deficits.

This would not be a problem if it were to put shoddy and unpopular institutions out of business. But it is a worry if it leads to regional “cold spots” in which affordable degrees become difficult to find. Or if it benefits complacent incumbents that trade on their reputation rather than their teaching. Mr Trump’s war on the Ivy League could have much wider effects than he bargained for. ■

Business | Bartleby

A short guide to salary negotiations

Don’t threaten. Do research

Illustration: Paul Blow

Jun 2nd 2025

Listen to this story

Talking about how much money you earn is uncomfortable for many people. But there are moments when it is an unavoidable topic of conversation. When you take a new job or learn how much your rise will be for the coming year, you have to talk about salaries. You also have to make a decision about whether to negotiate for more.

Negotiating does seem to pay off, at least in monetary terms. In its 2025 survey of American jobseekers, Employ, a recruiting-software provider, found that 37% of candidates had asked for more money, and that 80% of them had got more than their initial offer. That is consistent with a paper published in 2011 by Michelle Marks of the University of Colorado and Crystal Harold of Temple University, which found that candidates who chose to bargain bumped up their starting salaries by an average of $5,000 ($7,160 in today’s money).

Negotiating, which is the subject of this week’s episode of our Boss Class podcast, comes more naturally to some than others. A recent study by Jackson Lu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked at 19 consecutive years of MBA graduates from an American business school, and found that graduates of East Asian and South-East Asian ethnicity had markedly lower salaries than South Asians and whites. The propensity to negotiate among different groups explains the gap; East Asians and South-East Asians who did not try to negotiate were more likely to say they were concerned about damaging the relationship with an employer.

Women are more likely than men to worry about the effect of negotiating—with some cause. As part of a paper on salary negotiations published in 2024, Francesco Capozza of the Berlin Social Science Centre conducted a survey of HR managers in America. The respondents thought that candidates who attempted to negotiate on pay were less likely to receive a job offer than those who did not, and that this penalty hit women disproportionately hard.

If negotiating both raises salaries and risks a backlash, what is a bargainer to do? Leigh Thompson, who teaches at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, gives two pieces of advice to her MBA students as they look for work. One is not to start negotiating until you actually have a job offer (further evidence that MBAs may lack many things but confidence isn’t one of them). The other is not to turn a negotiation into a bidding war, deliberately playing potential employers off against each other to extract higher offers. Don’t be combative, she says. Don’t threaten.

Jim Sebenius, who teaches negotiating at Harvard Business School, advises scoping out the role as fully as possible and then finding the market rate for that sort of job. Information on pay is much easier to find than it was, owing to sites such as Glassdoor, and requirements in some places to publish salary ranges for advertised roles.

If candidates can attach themselves to a reasonable principle—that they only want to be paid the going rate—and point to evidence to back up their argument, that is more likely to work than arbitrary numbers, begging or threats to go elsewhere. Even if more money isn’t available, other things might be on the table: a promise to review pay after a certain period, named parking bays or whatever floats your boat.

It can be annoying for bosses to hear requests for more money, when all they really want is unbridled enthusiasm. But some employers actively want people to be good at negotiating. Photoroom is a French AI startup that makes photo-editing software; it offers negotiating training to anyone at the firm who wants it. Its primary goal is to enable engineers to buy kit fast without getting lost in red tape; the training helps them to do so at a good price.

Matt Rouif, its boss, says Photoroom also wants to know if it is paying below market rate; it buys in benchmark data on salaries and shares that data with employees so that conversations have a common starting-point. “A lot of people think it’s a fight. We’re trying to find the best outcome that looks fair.” That’s not a bad way for employees to frame a salary negotiation. ■

Business | Retail therapy

What Bicester Village says about the luxury industry

Everyone loves a bargain

England’s green and pleasant shopping centresPhotograph: Alamy

Jun 5th 2025|Bicester Village

Listen to this story

At first glance Bicester Village looks like any other in the Cotswolds, the bucolic corner of England it is located near. It is filled with low-rise buildings with gabled roofs, cobbled streets, wooden benches and greenery. It is, in fact, a shopping centre where designer brands, from Armani to Zegna, sell their wares at discounts of 30% or more. Announcements on the train from London come in Mandarin, as well as English, testament to its status as one of Britain’s most popular tourist destinations.

Bicester Village was built 30 years ago by Value Retail, a privately held group founded by Scott Malkin, whose father once owned the Empire State Building, and backed by L. Catterton, a private-equity firm part-owned by lvmh, a French luxury-goods giant. The group has since built 11 similar sites around wealthy cities including Shanghai and Milan. It seems shoppers can’t get enough of cut-price designer gear.

Value Retail takes 15-18% of sales plus a service fee from brands, rather than charging rent on their stores in its villages. As a private company it is coy about giving precise numbers but does say that it recorded double-digit growth in net sales in 2024 and it is on track for the same again this year. The firm reckons 50m people will visit its shopping centres in 2025. So what does the success of Value Retail say about the current state of the luxury industry?

Chart: The Economist

First and foremost, it is a sign that luxury brands are struggling. Demand for pricey frocks and handbags has drooped amid an economic slump in China and a cost-of-living crisis in the West. This in turn has prompted luxury brands to discount their wares and lean more heavily on bargain hunters. Of all the places for luxury shopping, including brands’ own shops and department stores, sales ticked up only in outlets last year, reckons Bain, a consultancy (see chart). As Mr Malkin puts it, in a downturn it becomes a “must have” for a label to have a store at one of his shopping centres, not a “nice to have”.

Value Retail’s growth also reflects changes in distribution. Brands are eager to take more control of discounting and customer experience to avoid damage to their image. In recent years luxury brands have sold more through their own shops, websites and concessions within department stores combined than through wholesale channels for the first time, according to Bain. This shift, says Anita Balchandani of McKinsey, another consultancy, is making outlets the “prime channel” through which brands are able to offload excess inventory.

As far as customers go, the throngs at Value Retail’s sites are evidence that in-person shopping is not going away. Returning unsuitable online purchases is a bother and the opportunity to see and touch items is still valued, especially for costly goods. bcg, yet another consultancy, estimates that 75-80% of luxury sales this year will take place in person.

Shoppers do, however, expect more from stores nowadays to make a visit worthwhile. That’s why Value Retail’s outlet centres boast fancy restaurants, storefronts pretty enough to post on social media and toilets that wouldn’t look out of place in a five-star hotel. vip customers at Bicester Village get access to a lounge and can use a “hands-free shopping” service, whereby shoppers can pick up all their purchases from one place when their spree is concluded.

Value Retail still faces limitations. Its carefully designed spaces and highly trained staff come at a high cost. There is only so much room for growth, too. The firm opened its first village in America last year. Expansion into other fast-growing markets, such as India and parts of the Middle East, is out of the question because of local regulations that complicate foreign investment, says Mr Malkin. That leaves a ceiling on the number of places around the world with droves of customers willing to drop large sums of money on discounted luxury goods. ■

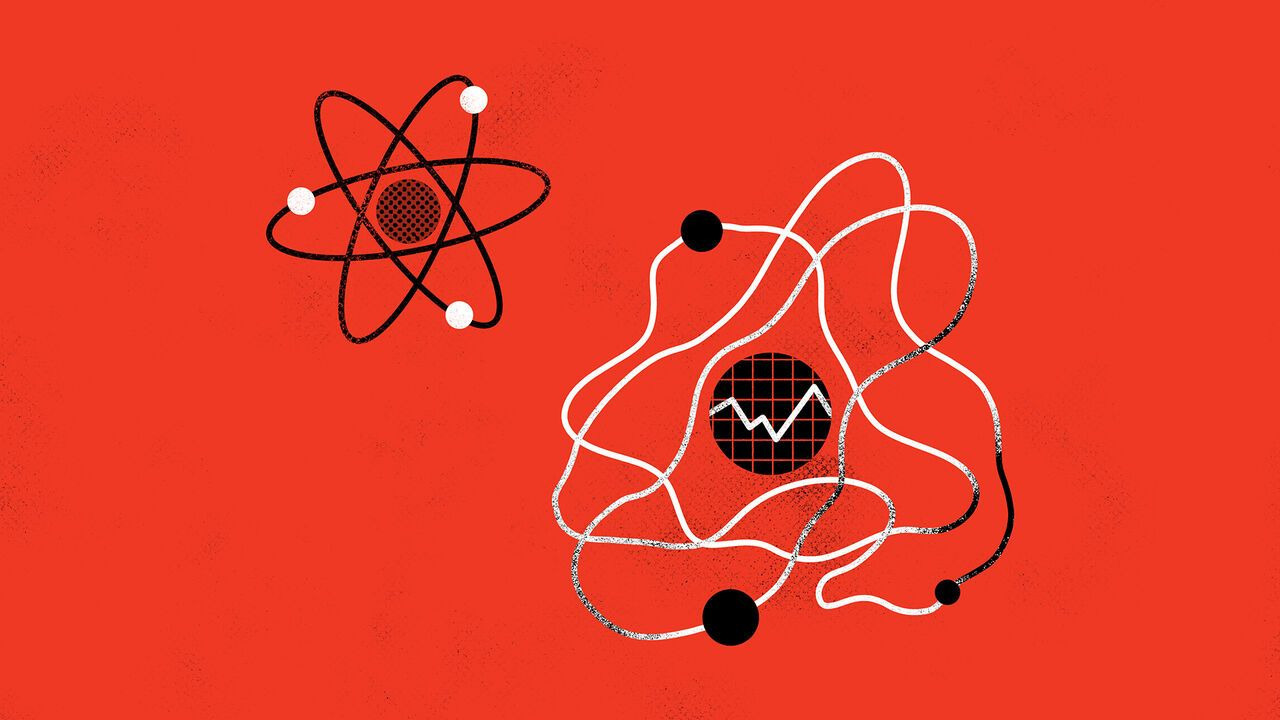

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Why investors lack a theory of everything

Markets have no fundamental laws, which is why they are so interesting

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Jun 4th 2025

Listen to this story

If there was to be some cataclysm, and he could preserve just one sentence for future scientists, Richard Feynman would have made it about atoms. Tell them everything was made of tiny particles in constant motion, thought the great 20th-century physicist, attracting and repelling each other along the way. With a little imagination they could then uncover the rest. That was because the universe had a marvellous feature: though vast, it could be described by surprisingly few laws. Armed with the knowledge of atoms, Feynman reckoned his successors could work some of these out and then deduce far more.

At first sight, the less illustrious field of financial theory resembles Feynman’s. A popular destination for recovering physicists, it includes many people who would have studied his old lectures as undergraduates. Some of the equations look similar, too. Were you to pick one branch of maths to teach a budding financial theorist, it would probably be stochastic calculus—the same one used to analyse the behaviour of Feynman’s jiggling atoms. Asset prices, after all, also jump around with seeming randomness. If you could specify how—and how they, too, jostle each other—you would have markets cracked for good.

But that is where finance and physics part ways, because the quest for the laws of markets is doomed. This is seldom as obvious as it has been recently, when the ground has been shifting and long-standing links between assets have snapped. Rich-world currencies normally strengthen when bond yields rise; no longer for the dollar and American Treasuries. Gold is supposed to do well when investors are panicking, and share prices when they are ebullient; now, both gold and plenty of stockmarkets are at or near all-time highs. The volatility implied by the options market is supposed to rise when things get riskier. It has been falling for months. Who, then, thinks markets have become safer—those dumping their dollars or snapping up gold?

There are plausible narratives to explain all these developments. But the reason investors reach for them is that they lack anything more concrete. Even physical laws that are merely approximate govern multitudes: Newton’s concerning gravity and motion got men to the moon, as well as explaining why apples fall. By contrast, all the financial candidates are both limited and empirically dubious.

The efficient-market hypothesis says that investors, in aggregate, perfectly and promptly incorporate new information into asset prices. It is an appealing thought, though not a convincing one if you have observed a crowd, a trading floor or a stockmarket bubble. Arbitrage theory, which says portfolios of assets with the same pay-offs must have the same price, is more useful. It governs how derivatives (contracts with pay-offs dependent on some underlying asset price) are valued by specifying how traders can replicate them. But the replication strategies it prescribes can come badly unstuck if prices jump sharply. Models relating risk to returns—such as the widely taught “capital asset pricing model”—usually make the maths tractable by assuming returns are distributed along a bell curve. Unfortunately, they are not.

None of these approaches the ideal theory of markets, which would fully explain how fundamentals move prices and how they sway each other. It is no surprise, then, that practitioners pursue narrower goals. The bright sparks who work at today’s dominant quantitative hedge funds are not searching for a theory of everything. They want to find links between assets that have held in the past, will hold in the near future and from which they can make money. One example is “trend following”, which does what it says after spotting a new pattern early. Another is “statistical arbitrage”, which searches for assets that usually move in a set relationship to each other, snapping back if they get out of line.

If that sounds unsatisfying to investors who are wondering what comes next, it is not the theorists’ fault. The complexity of markets is dizzying, and in complex situations even the iron laws of physics can produce surprising, unstable results (think of aeroplane turbulence). More important still, finance is ultimately driven by people, not particles, and they do not always respond to similar stimuli in similar ways. They look at what happened last time, try to do better, anticipate what other traders will do and seek to outfox them. The absence of fundamental laws in markets is frustrating, disorientating—and what makes them so interesting. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

Stanley Fischer mixed rigour and realism, compassion and calm

The former IMF, Bank of Israel and Federal Reserve official died on May 31st

Illustration: Álvaro Bernis

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

He looked ridiculous, his wife assured him. Stan Fischer, the number-two official at the IMF, was supposed to be enjoying a holiday on Martha’s Vineyard in July 1998. Instead, he was perched on a sand dune, mobile-phone at his ear, trying to negotiate a bail-out of Russia, a country deemed “too nuclear to fail”.

Russia’s crisis also ruined Mr Fischer’s next holiday on the Greek island of Mykonos. He had to fly back to Washington, records “The Chastening”, a book by Paul Blustein, huddled under a blanket so other passengers could not overhear his phone calls.

Mr Fischer, who died on May 31st aged 81, bore such indignities with stoical good humour. This composure, as well as his wisdom, endeared him to his peers, his staff and even the many emerging-market officials, “fear in their eyes”, who turned to the fund for help during his tenure from 1994 to 2001. They hailed from Mexico, Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Brazil and Argentina, as well as Russia. The Thai central bank, which had hidden the parlous state of its foreign-exchange reserves, eventually offered to reveal the true number. But only to Mr Fischer. One head of Brazil’s central bank refused to deal with IMF staffers, whose command of economics failed to impress him. But he spoke every day to Mr Fischer, whose credentials could not be doubted.