The Economist Articles for June. 4th week : June. 22nd(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.06.14조회수66 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for June. 4th week : June. 22nd(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Factory fever

The world must escape the manufacturing delusion

Governments’ obsession with factories is built on myths—and will be self-defeating

Jun 12th 2025

Listen to this story

Around the world, politicians are fixated on factories. President Donald Trump wants to bring home everything from steelmaking to drug production, and is putting up tariff barriers to do so. Britain is considering subsidising manufacturers’ energy bills; Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, is offering incentives for electric-vehicle-makers, adding to a long-running industrial-subsidy scheme. Governments from Germany to Indonesia have flirted with inducements for chip- and battery-makers. However, the global manufacturing push will not succeed. In fact, it is likely to do more harm than good.

Today’s zeal for homegrown manufacturing has many aims. In the West politicians want to revive well-paying factory work and restore the lost glory of their industrial heartlands; poorer countries want to foster development as well as jobs. The war in Ukraine, meanwhile, shows the importance of resilient supply chains, especially for arms and ammunition. Politicians hope that industrial prowess will somehow translate more broadly into national strength. Looming over all this is China’s tremendous manufacturing dominance, which inspires fear and envy in equal measure.

Jobs, growth and resilience are all worthy aims.

Unfortunately, however, the idea that promoting manufacturing is the way to achieve them is misguided. The reason is that it rests on a series of misconceptions about the nature of the modern economy.

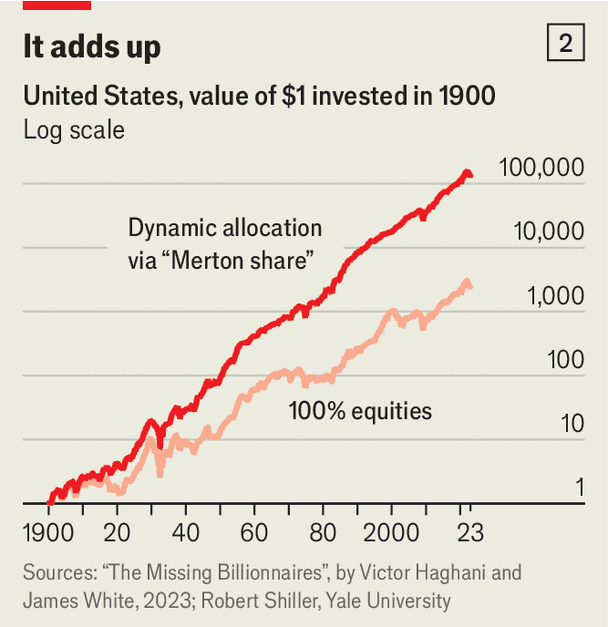

One concerns factory jobs. Politicians hope that boosting manufacturing means decent employment for workers without university degrees or, in developing countries, who have migrated from the countryside. But factory work has become highly automated. Globally, it provides 20m, or 6%, fewer jobs than in 2013, even as output has increased 5% by value. For all countries to take more of a shrinking pie is impossible.

Many of the good jobs created by today’s production lines are for technicians and engineers, not lunch-pail Joes. Less than a third of American manufacturing jobs today are production roles carried out by workers without a degree. By one estimate, bringing home enough manufacturing to close America’s trade deficit would create only enough new production jobs to account for an extra 1% of the workforce. Manufacturing no longer pays those without a degree more than other comparable jobs in industries such as construction. As productivity growth is lower in manufacturing than it is in service work, wage growth is likely to be disappointing, too.

Another misconception is that manufacturing is essential for economic growth. India’s manufacturing output, as a share of gdp, languishes about ten percentage points below Mr Modi’s target of 25%. But that has not stopped India’s economy growing at an impressive rate. In the past few years China has struggled to meet its growth targets, even as its manufacturers have come to dominate entire sectors, such as renewable energy and electric vehicles.

What about the argument that, given the war in Ukraine and tensions with China, the rich world must reindustrialise for the sake of national security? It seems dangerous to rely on factories abroad. And covid-19 caused a supply-chain panic. Some dependencies are indeed chokeholds. China’s near-monopoly in refining rare earths has recently allowed it to put the brakes on global carmaking, giving it leverage over America. It is also prudent for the West to build up stocks of weapons and ammunition, to ensure that crucial infrastructure is sourced from allies and to build things with long lead times, like ships, before conflict breaks out.

But in today’s ultra-specialised world, across-the-board subsidies for reindustrialisation will not do much to boost war-readiness. Making Tomahawks is entirely different from making Teslas. Far from suggesting that countries at peace must develop the capacity to make lots of drones, the war in Ukraine shows that a wartime economy can innovate and multiply production volumes remarkably fast.

The final part of the manufacturing delusion is the idea that China’s industrial might is a product of its state-led economy—and so must be countered with a similarly extensive industrial policy everywhere else. China does indeed distort its markets in all kinds of ways, and early in this century it manufactured an unusual amount given its level of development. But those days are past.

China has not escaped the global shrinkage of factory jobs since 2013. The share of its workforce in factories corresponds to America’s at a similar level of prosperity; and it is lower than it was in most other rich economies. China’s 29% share of global manufacturing value-added is a function of its size rather than its strategy. After years of fast growth, it now has an enormous domestic market to support its manufacturers. Innovation is begetting innovation; a “low-altitude economy” of drones and flying taxis promises to take flight soon. Yet, even though China’s goods exports have grown by 70% relative to global GDP since 2006, they have fallen by half as a share of the Chinese economy.

Factory settings

The way to rival the manufacturing heft of China is not through painful decoupling from its economy, but by ensuring that a sufficiently large bloc rivals it in size. This is best achieved if allies are able to work together and trade in an open and lightly regulated economy; factories in America, Germany, Japan and South Korea together add more value than those in China. As the pandemic showed, diverse supply chains are a lot more resilient than national ones.

Alas, governments today are heading in precisely the opposite direction. The manufacturing delusion is drawing countries into protecting domestic industry and competing for jobs that no longer exist. That will only lower wages, worsen productivity and blunt the incentive to innovate, while leaving China unrivalled in its industrial might. The mania for manufacturing is not just misguided. It is self-defeating. ■

Leaders | Strike it lucky

Israel has taken an audacious but terrifying gamble

The world would be safer if Iran abandoned its nuclear dreams, but that outcome may prove unattainable

Jun 13th 2025

FOR THREE decades, Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, has warned that Israel’s gravest external threat is Iran. And no Iranian threat is graver than its programme to acquire a nuclear bomb. Israel is a small, densely populated country within missile range of the Islamic Republic. A nuclear-armed Iran would put its very existence at risk.

Early on Friday June 13th, Mr Netanyahu at last acted on this conviction, dispatching wave after wave of Israeli aircraft to strike Iran. They attacked nuclear installations in Natanz, 300km south of the capital Tehran, as well as officials associated with the weapons programme. And they also killed the top echelons of the Iranian armed forces, including Mohamad Bagheri, the chief of staff.

Mr Netanyahu once had a reputation as a risk-averse leader, but this strike was audacious, even reckless. Israel is entitled to take action to stop Iran from getting a bomb. The prime minister is justified in fearing that a nuclear-armed Iran would hold dire consequences for his country. He appears to have the support of President Donald Trump, an essential ally. Friday’s assault could turn out to be a devastating blow against the regime in Tehran. But it also threatens a bewildering range of outcomes, including some that are bad for Israel and America.

Nobody familiar with the recent history of the Middle East could doubt that Israel is right to see Iran as a threat. The Islamic Republic has been a malign presence in the region, sponsoring terrorists, violent militias and despotic regimes, including that of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has repeatedly threatened to obliterate Israel. Iran backed Hamas, which launched a murderous attack on the country from Gaza on October 7th 2023.

An Iranian bomb would make all of this worse. It could lead countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia, to seek weapons of their own. Even without any proliferation, a nuclear-armed Iran would be perceived in the region as a constraint on the Israel Defence Forces’ freedom of manoeuvre. In Israel’s eyes, that would undermine the deterrence that keeps it safe in a dangerous neighbourhood.

Israeli officials argue that they would eventually have no choice but to attack Iran’s nuclear programme and that they had a brief window to carry one out. Iran is weaker than it has been for decades. Israel wrecked its air defences last year, in strikes undertaken as part of a tit-for-tat exchange. Not only is the regime unpopular, but its influence in Lebanon and Syria is much diminished. Hizbullah, the Lebanese militia that was once seen as the spearhead of any Iranian retaliation, no longer has the missiles or organisation to mount a serious reprisal.

More importantly, Israel insists, Iran has never been closer to going nuclear. It says that, having accelerated its production of enriched uranium, Iran now has enough for 15 bombs. In a recorded address, Mr Netanyahu claimed to have evidence that Iran is weaponising its technology, saying that it may be close to a device. His officials believe that, in talks with America about a deal that would halt the nuclear programme, Iran has been creating a smokescreen behind which its scientists were in reality pressing rapidly ahead. In a post, Mr Trump endorsed that view, accusing Iran of being unwilling to make a deal. If the talks were doomed, Israel believes, then it had to act now, before it was too late.

Perhaps with American help over the coming days, Israel may inflict fatal damage on Iran’s nuclear programme. Having killed many Iranian officials, it may have caused so much chaos in Tehran that the regime cannot mount a powerful response. After being on the receiving end of such a show of strength, the mullahs may be deterred from mounting another attempt to build a nuclear arsenal. That is the outcome which would best serve the Middle East and the world.

However, Friday’s offensive is also a huge gamble. For one thing, the urgency may not be as great as Israel suggests. In March America’s intelligence chief, Tulsi Gabbard, said that Mr Khamenei had not reauthorised the weapons programme he suspended in 2003. Even after the attacks, Mr Trump continued to believe that there was scope for talks, calling on Iran to return to the negotiating table and strike a deal. Should Iran agree, a remote possibility, this could yet become a source of friction between America and Israel. Mr Netanyahu has never trusted Iran to abide by agreements to limit its nuclear programme.

The strike is also a gamble because of its potential regional and global consequences. Although Iran is less able to retaliate than it once was, it can still cause a lot of harm. Already, on June 13th Iran loosed over 100 drones against Israel. Iran could launch attacks on the Gulf states that are American allies or host American bases. It can still call on the Houthis, its proxies in Yemen. And it could also wage a campaign of terror against Israeli or Jewish interests around the world. If this descended into a regional war, there could be consequences for stability and—via oil prices—for the rest of the world.

Odd as it may sound, a collapse of the rotten Iranian regime, much as it is hated within the country and in the region, could also be highly destabilising. Iran is a big and complex country without a history of democracy. Nobody can say what might emerge from the chaos.

But the main reason the strike is a gamble is that it may not work. Twice before, in Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007, Israel attacked nuclear-weapons programmes and successfully halted them. Iran’s effort is much more advanced and dispersed than those ever were. Its facility at Fordow, in Qom province, is safely hidden beneath a mountain. If, as some officials believe, that puts it beyond reach of Israeli munitions, Israel would require ground troops or American help to put it out of action. Even if physical infrastructure is destroyed, Iran has its own deposits of uranium. In the past few decades it has mastered the process of enrichment. Geology and knowhow lie beyond the reach of even American bombs. If the Iranian programme is restarted, it may return more virulent and threatening than ever.

The prospect is therefore that, within a few years, Israel and possibly America will be obliged to repeat the operation all over again. Each time will be harder than the last. Even in a world where the old rules are breaking down, an endless pattern of regular bombing raids on a sovereign nation would carry a heavy diplomatic and political cost. Eventually, repeated strikes could stretch America’s patience and inflame public opinion there, doing long-term harm to the alliance with America upon which Israel depends.

Mr Netanyahu will argue that none of these arguments weighs more heavily than his country’s survival and that he simply cannot afford to let talks with Iran play out. It is an all-or-nothing worldview that has led Israel into wars in Gaza, Lebanon and now Iran.

The hope is that Iran’s nuclear programme will be destroyed never to return. That would be vindication for Israel’s prime minister. But if not, Israel will have to live with the paradox that Mr Netanyahu engenders. At a time when the Gulf states are offering a new vision of the Arab world built on the coexistence with Israel that comes from economic development, his eagerness to resort to conflict risks making their plans impossible. In attempting to spare the Middle East from Iranian aggression, he risks trapping it in a cycle of violent destruction and instability. In its own way, that poses an existential threat to Israel, too. ■

Leaders | Phew, it’s a girl!

The stunning decline of the preference for having boys

Millions of girls were aborted for being girls. Now parents often lean towards them

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

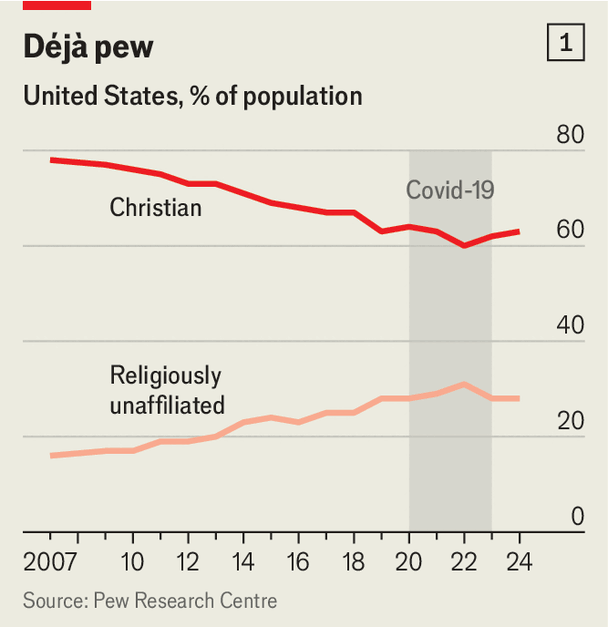

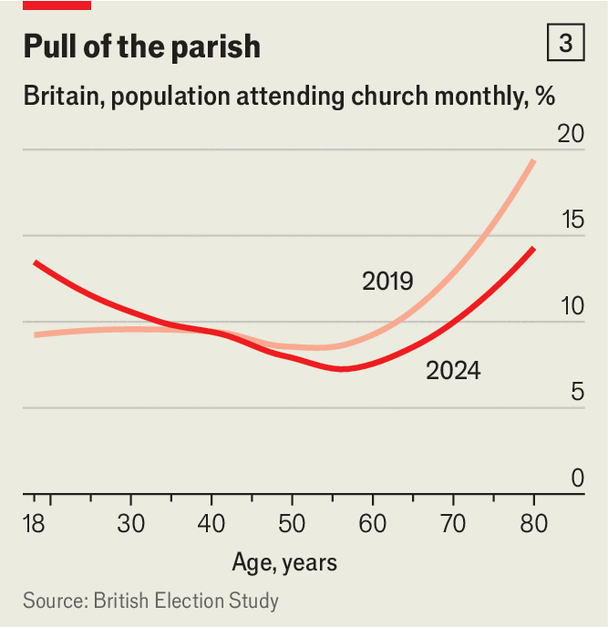

Without fanfare, something remarkable has happened. The noxious practice of aborting girls simply for being girls has become dramatically less common. It first became widespread in the late 1980s, as cheap ultrasound machines made it easy to determine the sex of a fetus. Parents who were desperate for a boy but did not want a large family—or, in China, were not allowed one—started routinely terminating females. Globally, among babies born in 2000, a staggering 1.6m girls were missing from the number you would expect, given the natural sex ratio at birth. This year that number is likely to be 200,000—and it is still falling.

The fading of boy preference in regions where it was strongest has been astonishingly rapid. The natural ratio is about 105 boy babies for every 100 girls; because boys are slightly more likely to die young, this leads to rough parity at reproductive age. The sex ratio at birth, once wildly skewed across Asia, has become more even. In China it fell from a peak of 117.8 boys per 100 girls in 2006 to 109.8 last year, and in India from 109.6 in 2010 to 106.8. In South Korea it is now completely back to normal, having been a shocking 115.7 in 1990.

In 2010 an Economist cover called the mass abortion of girls “gendercide”. The global decline of this scourge is a blessing. First, it implies an ebbing of the traditions that underpinned it: the stark belief that men matter more and the expectation in some cultures that a daughter will grow up to serve her husband’s family, so parents need a son to look after them in old age. Such sexist ideas have not vanished, but evidence that they are fading is welcome.

Second, it heralds an easing of the harms caused by surplus men. Sex-selective abortion doomed millions of males to lifelong bachelorhood. Many of these “bare branches”, as they are known in China, resented it intensely. And their fury was socially destabilising, since young, frustrated bachelors are more prone to violence. One study of six Asian countries found that warped sex ratios led to an increase of rape in all of them. Others linked the imbalance to a rise in violent crime in China, along with authoritarian policing to quell it, and to a heightened risk of civil strife or even war in other countries. The fading of boy preference will make much of the world safer.

In some regions, meanwhile, a new preference is emerging: for girls. It is far milder. Parents are not aborting boys for being boys. No big country yet has a noticeable surplus of girls. Rather, girl preference can be seen in other measures, such as polls and fertility patterns. Among Japanese couples who want only one child, girls are strongly preferred. Across the world, parents typically want a mix. But in America and Scandinavia couples are likelier to have more children if their early ones are male, suggesting that more keep trying for a girl than do so for a boy. When seeking to adopt, couples pay extra for a girl. When undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and other sex-selection methods in countries where it is legal to choose the sex of the embryo, women increasingly opt for daughters.

People prefer girls for all sorts of reasons. Some think they will be easier to bring up, or cherish what they see as feminine traits. In some countries they may assume that looking after elderly parents is a daughter’s job.

However, the new girl preference also reflects increasing worries about boys’ prospects. Boys have always been more likely to get into trouble: globally, 93% of jailbirds are male. In much of the world they have also fallen behind girls academically. In rich countries 54% of young women have a tertiary degree, compared with 41% of young men. Men are still over-represented at the top, in boardrooms, but also at the bottom, angrily shutting themselves in their bedrooms.

Governments are rightly concerned about boys’ problems. Because boys mature later than girls, there is a case for holding them back a year at school. More male teachers, especially at primary school, where there are hardly any, might give them role models. Better vocational training might nudge them into jobs that men have long avoided, such as nursing. Tailoring policies to help struggling boys need not mean disadvantaging girls, any more than prescribing glasses for someone with bad eyesight hurts those with 20/20 vision.

In the future, technology will offer parents more options. Some will be relatively uncontroversial: when it is possible to tweak genes to avoid horrific hereditary diseases, those who can will not hesitate to do so. But what if new technologies for sex selection become widespread? Couples undergoing fertility treatment can already choose sperm with X chromosomes or determine an embryo’s sex via genetic testing. Such techniques are expensive and rare, but will surely get cheaper.

Also, and more important, more parents who conceive children the old-fashioned way are likely to use cheap, blood-based screening in the first weeks of pregnancy to find out about genetic traits. These tests can already reveal the sex of the embryo. Some people trying for a girl may then use pill-based abortifacients to avoid having a boy. As a liberal newspaper, The Economist would prefer not to tell people what kind of family they should have. Nonetheless, it is worth pondering what the consequences might be if a new imbalance were to arise: a future generation with substantially more women than men.

The power of numbers

It would not be as bad as too many men. A surplus of single women is unlikely to become physically abusive. Indeed, you might speculate that a mostly female world would be more peaceful and better run. But if women were ever to make up a large majority, some men might exploit their stronger bargaining position in the mating market by becoming more promiscuous or reluctant to commit themselves to a relationship. For many heterosexual women, this would make dating harder. Some wanting to couple up would be unable to do so.

Celebrate the cooling of the war on baby girls, therefore, and urge on the day when it ends entirely. But do not assume that what comes next will be simple or trouble-free. ■

Business | Schumpeter

AI agents are turning Salesforce and SAP into rivals

Artificial intelligence is blurring the distinction between front office and back office

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

ENTERPRISE SOFTWARE is an unlikely source of hubbub. Bringing up CRM or ERP in conversation has usually been a reliable way to be left alone. But not these days, especially if you are chatting to a tech investor. Mention the acronyms—for customer-relationship management, which automates front-office tasks like dealing with clients, and enterprise resource planning, which does the same for back-office processes such as managing a firm’s finances or supply chains—and you will set pulses racing.

Between June and early December 2024 Salesforce, the 26-year-old global CRM giant, created more than $120bn in shareholder value, lifting its market capitalisation to a record $352bn. In the past 12 months SAP, a German tech titan which more or less invented ERP in the 1970s, has generated more. It is Europe’s most valuable company, worth $380bn, likewise an all-time high. Both enterprise champions rank among the world’s top ten software companies by value. Maybe not so dull, after all?

The source of the excitement is another, much sexier acronym: AI. Builders of clever artificial-intelligence models may get all the attention; this week Elon Musk’s xAI hogged the headlines when it was reported that the startup was launching a $300m share sale that would value it at $113bn. But if the technology is to be as revolutionary as boosters claim, it will in the first instance be because businesses use it to radically improve productivity. And as anyone who has tried—and probably failed—to replace corporate computer systems will tell you, they are likely to do so with the assistance of their current IT vendors.

Salesforce and SAP each believes it will be the one ushering its clients into the AI age. The trouble is that many of those clients use both firms’ products. Perhaps nine in ten Fortune 500 firms run Salesforce software. The same share relies on SAP.

This did not matter when the duo focused on their respective bread and butter. A client would run Salesforce’s second-to-none CRM in the front office and SAP’s first-rate ERP in the back. Amazon and Walmart, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, BMW and Toyota: pick a household name and the odds are it does just that.

A big reason for SAP and Salesforce to slather a thick layer of AI on top of their existing offering, though, is to give customers a way to uncurdle their data, analyse it and, with the help of semi-autonomous AI agents interacting with one another on behalf of their human managers, act on it. In this newly blended world, the lines between front and back office are fudged. “It’s one user experience,” sums up Irfan Khan, SAP’s data-and-analytics chief.

Controlling the user interface for this “agentic” AI experience promises fat profits. It also creates a head-to-head rivalry between the two enterprise masterchefs. For their AI recipes look alike.

Step one: expand your range of products. SAP has improved its front-office chops by buying CRM firms (like CallidusCloud) and marketing platforms (such as Emarsys). Though Salesforce has not gone full-ERP, it has a 16-year-old partnership with Certinia, whose financial-management system sits exclusively atop its platform. It has bought firms like ClickSoftware, which helps businesses manage their service workforce. On June 2nd it hired the team behind MoonHub, a recruitment-and-HR startup. Clients, spared from switching between providers for every specialist function, love it. So do SAP and Salesforce, since it amasses more client data, AI’s great leavener, in their own systems.

Step two: piggyback on the “hyperscalers”. This allows clients to choose between the cloud giants, including, in China, Alibaba and Tencent (and, in Salesforce’s case, excluding Microsoft, with which its co-founder and boss, Marc Benioff, has a long-running feud). It saves SAP and Salesforce from splurging on what each sees as infrastructure destined for “commoditisation”. Oracle, the giant of corporate-database management which has taken the opposite approach, has seen its quarterly capital budget explode from $400m in 2020 to nearly $6bn in its latest quarter; SAP and Salesforce spend $300m-400m a quarter between them.

Step three: whip up the AI layer. In February SAP teamed up with Databricks, a $60bn AI startup, to help clients make sense of their information, including that stored outside SAP systems, and deploy SAP’s Joule AI agents across their operations. On May 27th Salesforce said it would pay $8bn for Informatica, which designs tools to integrate and crunch corporate data. This will make its own Agentforce easier for clients to use beyond the front office.

Right now investors prefer what SAP is serving up. Its systems cover a wider range of functions and thus contain more data. This data is also notoriously hard for non-SAP systems to extract. As annoying as this may be for clients, it gives them an incentive to look from inside the SAP platform out rather than the other way round. SAP’s share price has risen by 12% in the past six months.

Meanwhile, Salesforce’s has collapsed like a bad soufflé. It is down by nearly 30% since its peak in early December. Although its sales passed those of SAP in 2023, growth is slowing while SAP’s accelerates. Analysts wonder if Agentforce, the launch of which fuelled last year’s rally, can make real money. They also fear a return to profligate dealmaking that culminated with the $28bn purchase in 2021 of Slack, a corporate-messaging platform.

Too many cooks

Investors could yet sour on SAP just as they have on Salesforce. Gartner, a research firm, reckons that between 2020 and 2024 rivals like Workday cut its share of the ERP business from 21% to 14%. For all its front-office efforts, its CRM sales declined around that time, even as Salesforce preserved its 20% slice of a growing market. Microsoft, which has its own cloud, its own cutting-edge AI and plenty of business clients, is elbowing its way into ERP, as well as CRM. The enterprise-AI food fight is just beginning. ■

Asia | Horns of a dilemma

If China invaded Taiwan, who would enter the war?

Japan and the Philippines would struggle to stay out. But what about the rest?

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025|Singapore

Listen to this story

“THE ELEPHANT in the room”, acknowledged Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, speaking to an audience of defence bigwigs at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on May 30th, “is the day China decides a big [military] operation.” Would France intervene on day one of such a war, he mused? “I would be very cautious today.”

Mr Macron’s ambivalence is widely shared. If China were to invade Taiwan, no one is certain how different countries would line up. A new paper by the Centre for a New American Security (CNAS), a think-tank in Washington, examines that question. If America stayed out of the war, it suggests, everyone else would, too. Speaking in Singapore, Pete Hegseth, America’s defence secretary, sought to dispel that thought. “Any attempt by Communist China to conquer Taiwan by force would result in devastating consequences,” he said. “Our goal is to prevent war, to make the costs too high.”

In practice, many Asian allies fear that America is getting wobblier on the issue. Last year Donald Trump said that he would “have to negotiate things” before coming to the island’s aid; some in the Pentagon see the Taiwanese as perhaps even a lost cause.

If America does step in, the two allies most severely affected would be Japan and the Philippines. Neither country would be enthusiastic about direct involvement, though. Japan’s participation would be unlikely to go much further than submarine patrols or missile strikes, argues CNAS. The Philippines, which has 175,000 citizens in Taiwan, would be more cautious still. But if China’s armed forces were bogged down, it could be tempted to grab territory in the South China Sea, where it has multiple disputes with China, suggest the authors. All this would depend on whether China had first attacked American bases in those two countries to pre-empt American involvement or whether it held back, hoping to secure American neutrality.

A second group of countries—South Korea, Australia and India—would be more insulated. But America would put pressure on each one to help. South Korea’s immediate concern would be deterring North Korea from exploiting any diversion of American forces. The country might offer “rear-area support”, such as logistical assistance, reckons CNAS.

Australia has become an increasingly important base for American forces, too. It has not formally pledged to join a war over Taiwan, even in private. But Australian officials acknowledge that their relationship with America, including the AUKUS nuclear submarine pact, could be in jeopardy if they stayed out. India would almost certainly focus on defending its land border with China, but America could probably count on co-operation on intelligence and anti-submarine warfare.

Then there is South-East Asia. Around 900,000 passport-holders from the region live and work in Taiwan, notes CNAS, accounting for 90% of foreign citizens there. Many countries would probably attempt to remain neutral, not least because China is by far the most important trading partner for most of the region. But America would probably push for access to Thai and Singaporean air and naval bases.

What about Europe? France and Italy have recently sent aircraft-carriers to the region; Britain has one en route. In private, European policymakers are increasingly concerned about a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. A handful could offer cyber and space capabilities. More consequential would be a decision by the EU to impose sanctions on China. In particular, writes Agathe Demarais of the European Council on Foreign Relations, another think-tank, a ban on Chinese imports to Europe “could be game-changing”. For now that is an exceedingly tall order. ■

China | Great rejuvenation, grim departure

Would you want to know if you were terminally ill?

In China, catastrophic diagnoses are often kept from patients

Things need not be so darkPhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025|Beijing

Listen to this story

QUALITY OF LIFE in China has soared in recent decades. The quality of death, however, remains grim. As the population ages, the number succumbing to diseases that can be protracted and painful, such as cancer and Alzheimer’s, is soaring. The government wants to make dying a bit less execrable, so it is experimenting with state-subsidised end-of-life care. But deep taboos and bureaucratic hurdles are making progress agonisingly slow.

International rankings confirm that China is one of the worst places to die. A study in 2015 by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), a sister organisation of this newspaper, placed China 71st out of 80 countries for the quality of palliative care. Another international study, published by the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, ranked China 53rd in its comparison of end-of-life care in 81 countries (Britain was top; America came in 43rd).

Chinese hospitals often do not allow patients to occupy beds simply to receive palliative care. Even at one of Beijing’s top hospitals (which does), only one-third of the patients who need such help can get it, a doctor told state media last year. Separate institutions for the dying are scant, too. For a terminally ill patient, there are often only two options: persist with hospital treatment that is expensive and ineffective, or die at home without ready access to powerful painkillers or help from well-trained nurses.

Taboos that limit discussion of death make all this harder to fix. It is common for doctors not to tell patients when they are terminally ill. Family members get told first—and they themselves sometimes decline to pass on the bad news. This can make it difficult to move someone to a hospice bed, even when one is available. Chinese tradition emphasises the importance of filial duty. People feel they are failing their parents if they give up on attempts to stop them dying. “We knew that treatment was pointless, but I covered it up and took her to Shanghai for surgery,” writes one woman on social media, about her mother’s cancer. “In the end, it was nothing but pain and disappointment.”

Efforts to set up dedicated hospices have sometimes faced opposition from neighbours fearful of living near a place linked with death. Li Wei, the founder of Songtang Hospice—a rare private institution in Beijing—recalls ordeals he faced after setting it up in 1987. The facility used rented property and had to move several times because landlords wanted to redevelop it. On one occasion occupants of an apartment complex gathered to stop the hospice moving in. Dozens of patients were left stranded outdoors in the summer heat with equipment piled around them.

Going gently

The good news is that attitudes towards hospice care have changed considerably in the past decade. Instead of lashing out as they usually do when China is criticised abroad, state media accepted the findings of the EIU’s big study. In 2016 hospice care was mentioned for the first time in a major health-related policy document issued by the central government. In its outline of goals for 2030, it said the building of hospice facilities should be “stepped up”. The following year China launched experiments in several cities. They include requiring health authorities to provide hospice beds in hospitals and offer palliative care at home.

Shanghai took the lead: by 2020 community health centres in every district were providing inpatient or home-based hospice care. Last year Beijing achieved the same. Between 2018 and the end of 2022, the number of hospice units in Chinese hospitals increased 15-fold to more than 4,200.

Yet the number of beds for palliative care remains “a drop in the bucket when considering the annual tens of millions of deaths in China”, noted Yicai, a news service, last year. Although some of the pilot schemes help patients by allowing some hospice treatment to be claimed on insurance, the biggest cost in palliative care—nursing—is not usually covered. And there is little real incentive, beyond government pressure, for underfunded hospitals to provide these services: peddling more expensive treatments is better for their bottom lines. In other rich countries hospice networks rely heavily on charitable donations. But these are far less available in China, not least because the party is wary of letting civil society flourish.

Another problem with the pilot schemes is that they do not tackle a glaring unfairness in China’s health-care system. When using urban medical services, many migrants from the countryside (there are about 300m such people) have to pay a far higher proportion of their expenses out of pocket than they would if they received the same treatment in their hometowns. And hospice wards are mostly in big cities.

It will not get easier. As China’s property market falters, one of the main sources of revenue for local governments—land sales—is drying up. It is no coincidence that the biggest progress towards rolling out hospice care is being made in the richest parts of the country. Poorer ones have little incentive to launch new public services that are not self-sustaining financially. In addition to providing beds, hospitals would have to devote considerable resources to training staff in what for most would be an unfamiliar area of expertise. In most of China a dignified, comfortable death will remain a luxury that only the rich can afford. ■

China | Can’t buy me love

Bride prices are surging in China

Why is the government struggling to curb them?

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025

Listen to this story

MARRIAGE IN CHINA can be mercenary. “Is 380,000 yuan a lot for a bride price?” a woman in Guangdong asks on a social-media site. She is thinking of getting married, and wants to know how much her fiancé’s family should pay for her hand. The sum she is suggesting, equivalent to nearly $53,000, is more than seven times her annual wage. Thousands reply; many say she should demand more. “Sis, life is your own, don’t wrong yourself, at least ask for 888,800,” says one.

In many countries the custom of paying a “bride price” has faded as people have become richer. Not in China, where the practice remains deeply entrenched. In some parts of the country bride prices are an endowment passed by the groom’s parents to the newlyweds. In others, it is a compensation paid entirely to the bride’s family. In both cases, the amounts involved are going up.

The median bride price for marriages in the countryside doubled in real terms between 2005 and 2020, according to a recent paper by Yifeng Wan of Johns Hopkins University. Prices in urban areas are rising, too. A bride price of 380,000 yuan would indeed be steep in Guangdong province, where the median was about 42,000 yuan when last estimated. But it would look a bit less outrageous in neighbouring Fujian, where 115,000 yuan is the norm.

The government disapproves. It wants more marriages, in part to boost China’s low birth rate. Lofty bride prices do not help with that. Officials desire in particular to curb them in the countryside, where they are very high, relative to incomes. Sometimes acquiring the necessary money can plunge a groom’s family into poverty.

Since 2019 the Communist Party has routinely called for efforts to tackle the problem. Yet little progress has been made—even though Chinese law bans “the exaction of money or gifts in connection with marriage”. Village officials often avoid interfering, out of respect for local custom and for fear of getting caught between bickering families. Various places have introduced caps, but these are sometimes high: 50,000-80,000 yuan in parts of Gansu province, for example.

In May state media said Gansu’s government had circulated a plan to “effectively control” high bride-prices by the end of this year and “gradually reduce” them in 2026. But the measures in its plan look fairly meagre: there seem to be no penalties.

The desperation of some men for a bride is a big obstacle to change. There is a huge imbalance of the sexes: by 2027 China will have 119 men for every 100 women in peak marrying-age groups. Women, too, resist reform. Many see bride prices as a hedge against divorce (marriages in China fail more often than in America). Should the marriage end, part of the bride price might be returned. But a big share can remain with the female divorcee.

Some Chinese argue that bride prices commodify women. In recent weeks men and women have been fighting online over a case involving a man convicted of raping his fiancée after his family made a betrothal gift of 100,000 yuan: some dinosaurs say that accepting such sums implies consent to sex. But many Chinese are coolly pragmatic about demands for cash. “Money is the foundation of everything,” writes one woman on Weibo, a social-media site: “You might not care about it in your heart, but if the other side doesn’t even want to give it, that’s a problem.” ■

United States | Lexington

The true meaning of Trump Derangement Syndrome

His partnership with Elon Musk is the Rosetta Stone

Illustration: David Simonds

Jun 12th 2025

Listen to this story

Elon Musk said Donald Trump should be impeached and that he was covering up his ties to an accused sex trafficker. Mr Trump said Mr Musk, whom he had put in charge of eliminating waste and fraud in the government, had ignored the easiest way to do the job, cutting his own government contracts. He also said Mr Musk had lost his mind. Do any of these accusations matter? Probably not, at least not nearly as much as they seemed to at the time, lo these few days ago, when they were riveting national and even global attention.

Already, in a concession to the leverage each man holds, the two are making nice with each other. Illegal immigration, the problem that has always made Mr Trump beloved by his base and at least acceptable to enough other Americans, helped the president change the subject and the businessman reingratiate himself. Mr Musk tweeted approvingly about Mr Trump’s militarised response to demonstrations in Los Angeles that turned violent, and Mr Trump told reporters he wished Mr Musk “very well”. By June 11th Mr Musk was publicly regretting “some” of his posts.

Since Mr Trump began taking control of the Republican Party more than a decade ago, it has often been noted that he was succeeding in “normalising” behaviour that would have once scandalised members of both parties, from freely using expletives in speeches to scoffing at the sacrifices of American war heroes to making outrageous insinuations about adversaries—whether that Barack Obama was a foreign-born Muslim, that Ted Cruz’s father had a link to the killing of John F. Kennedy or that Kamala Harris was cognitively impaired. But “normalisation” has always been the wrong way to think about Mr Trump’s peculiar achievement. If his antics were becoming normal, they would not continue to command the spotlight. An outrage is not outrageous if it is normal.

What Mr Trump succeeds in doing is trivialising obnoxious and even corrosive conduct. Where normalisation still invites accountability—that’s normal, after all—trivialisation defies it. The alliance with Mr Musk has been the most extreme instance of Mr Trump’s politics of trivialisation, in which outrageous abnormality after outrageous abnormality has whetted more interest in speculating about the next abnormality than in weighing the consequences of what has happened. Rather than just move on, let us reckon with a few features of their partnership—so far—that have had little if any precedent in American history.

Mr Musk spent more than a quarter of a billion dollars in a matter of months to help elect Mr Trump last year, including through a “lottery” awarding $1m each day to a registered voter in Pennsylvania. During Mr Trump’s transition, Mr Musk advised him about staff, sat in on his meetings with foreign leaders and accepted responsibility for overhauling the entire federal government. His companies not only had billions in federal contracts; they were subject to more than two dozen federal investigations and enmeshed with governments around the world. The White House waved away concerns about conflicts of interest with assurances that Mr Musk would voluntarily avoid any.

The very name of Mr Musk’s operation, the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, was a joke, a smirking reference to a meme coin Mr Musk had made fun of for years. Mr Musk blitzed minions into targeted agencies to commandeer their information-technology systems and use them to cancel contracts and fire people, apparently without considering what they did. Agencies wound up frantically rehiring specialists who safeguarded nuclear weapons, protected against bird flu or calculated interest-rate tables to rationalise the mortgage market. Thousands of other federal workers have lost their jobs, but the precise number is uncertain because DOGE cuts are still working their way through the courts, and because DOGE’s statistics have proved far less trustworthy than those of the bureaucracy Mr Musk scorned.

The principal agency for foreign development, USAID, was authorised and funded by Congress. But Mr Musk did not ask Congress to reconsider, let alone to grant him permission, before chortling on X that he had sent the agency “into the woodchipper”. No doubt the spending was not all wise. And maybe hundreds of thousands of people have not died already, as one academic has estimated. Still, that number is surely not zero, as the secretary of state, Marco Rubio, testified it was to Congress last month.

“The picture of the world’s richest man killing the world’s poorest children is not a pretty one,” Bill Gates told the Financial Times. That judgment may haunt those in Washington—Mr Rubio used to be one—who valued foreign aid. Still others may remain offended by DOGE’s overpromising, sloppiness and glibness. But all that seems somehow beside the point now, fading as memories of “Liberation Day” should not be but are, as Mr Trump sends the Marines into Los Angeles and works to ram his overstuffed, deficit-amping, DOGE-deriding budget bill through the Senate.

A small beautiful bill

That bill was ostensibly the reason Mr Musk erupted, because it undermined DOGE’s work. He called it “a disgusting abomination”. (Though who would bet he will focus on persuading Republicans to oppose it?) For his part, Mr Trump said during the spat that Mr Musk suffered from “Trump Derangement Syndrome”, brought on by how much he missed working for the president.

As it happens, two House Republicans introduced a bill last month to get to the bottom of this phenomenon. The bill instructs the National Institutes of Health to spend precious federal dollars to “conduct or support research to advance the understanding of Trump Derangement Syndrome, including its origins, manifestations, and long-term effects”. What more perfect demonstration could there be of the syndrome itself? ■

United States | California screamin’

The meaning of the protests in Los Angeles

Donald Trump’s provocation could change LA, California and perhaps the entire country

Photograph: Reuters

Jun 12th 2025|Los Angeles

Listen to this story

THE MOOD changed by the moment. On June 8th a woman hugged her two young daughters on a bridge overlooking the 101 freeway in downtown Los Angeles. Vendors sold Mexican flags and protesters adjusted the rhythms of their chants. “Move ICE get out the way” morphed into “Donald Trump, let’s be clear, immigrants are welcome here”. It felt like a neighbourhood block party—if block parties encouraged graffiti. But chants turned to screams as police exploded flash-bang grenades to clear the road. The two young girls grimaced and hustled away. California Highway Patrol officers paced in riot gear, their less-lethal weapons aimed at the crowd. Some protesters lobbed bottles at police, who dodged the projectiles.

Nearby, several Waymo driverless cars were set aflame.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had conducted several raids across Los Angeles County, which sparked protests. Mr Trump likened them to a “rebellion” and invoked a rarely used statute to deploy at least 2,000 members of the California National Guard to LA to protect federal agents and property, against the wishes of California’s state and local officials. This overreaction galvanised Angelenos and turned what were isolated clashes between protesters and federal agents into general unrest that swallowed parts of downtown. Since then, Mr Trump has doubled the number of guardsmen and added 700 active-duty marines to the mix.

Mr Trump’s political success since 2016 can be partially explained by his talent for rallying his supporters against a common enemy, whether that be illegal immigrants, Democrat-run cities, or, in this case, both. That his first reaction was to reach for the military suggests that the move was meant as a provocation, as if he were daring Angelenos to resist, thereby justifying his decision to call in troops and proving to his followers that Democrats will raise hell to shield immigrants from deportation. Local leaders urged protesters to stay peaceful lest they offer Mr Trump a reason to invoke the Insurrection Act, a law from 1807 that gives the president the power to deploy the military to help quell domestic uprisings. He has not ruled that out. The troops’ deployment has already traumatised Los Angeles and turned a tense relationship between California and the Trump administration into a hostile one. What happens next will determine whether the unrest in LA fades, or sparks a national movement.

LA was already having a bad year. Raging wildfires in January killed 30 people, incinerated two neighbourhoods and left locals angry at their leaders. A survey from the University of California, Los Angeles, in April found that just 37% of Angelenos viewed Karen Bass, the city’s mayor, favourably, down from 42% a year ago. Now the president is piling on. During a speech at Fort Bragg on June 10th Mr Trump expressed disdain for his country’s second-largest city, calling it “a trash heap” in need of liberation. Ms Bass is trying to strike a balance by promising to punish protesters who got violent, while defending LA’s massive immigrant community (roughly one-third of the county’s 10m people are foreign-born).

The unrest could unite the city against the administration, but right now it seems more likely to sow division. Several protest leaders stood on a truck bed in front of City Hall and decried Mr Trump, ICE—and their local leaders. “If Karen Bass can’t protect us, if the city council can’t protect us, if the Democratic Party can’t protect us, who’s going to protect us?”, asked one young man. The answer, he argued, isn’t just rebellion but “revolution”.

Still, LA has seen worse. More than 220 people have been arrested so far and Gavin Newsom, California’s Democratic governor, promises that number will grow. In 1992 thousands of people were arrested and 63 were killed when Angelenos rioted after police officers were acquitted of beating Rodney King, a black motorist. Across most of the city there was no sign that anything unusual was happening, except perhaps the circling helicopters. Even downtown, protesters ambled past “Fuck ICE” graffiti to admire the violet buds of the blooming Jacaranda trees. That duality is part of the city’s character: LA promises a sun-drenched dreamscape but sometimes delivers something closer to the darkness and moral ambiguity of film noir.

The unrest pits California squarely against the Trump administration. It was not an easy relationship to begin with. The liberal politics of America’s most-populous state make it a favourite target of the Republican Party. Mr Trump attacked Kamala Harris last year as a “San Francisco radical” who would turn America into California. When Mr Trump was inaugurated in January, Mr Newsom played nice: he needed the feds to help pay for LA’s recovery from the fires.

Things began to devolve even before the recent immigration raids. Last month the Republican-led Senate voted to revoke a waiver California uses to set stricter emissions standards than the federal government, and the administration said it would claw back federal dollars for the state’s boondoggle of a bullet train. California, meanwhile, is involved in at least 22 lawsuits against the administration, including a new one questioning the legality of Mr Trump’s deployment of troops to Los Angeles.

Though Mr Newsom and Mr Trump are on opposite ends of the political spectrum, they share a love of the limelight. When Tom Homan, the president’s border czar, threatened to arrest the governor for allegedly interfering with immigration enforcement, Mr Newsom told him to “come after me, arrest me, let’s just get it over with”. Mr Homan backed down, even if his boss didn’t. “I would do it,” Mr Trump told the press outside of the White House. “I like Gavin Newsom, he’s a nice guy, but he’s grossly incompetent.” Their catty spats can be mutually beneficial. The president titillates his base by attacking the governor, and Mr Newsom raises his national profile, perhaps with 2028 in mind, by presenting himself as the anti-Trump.

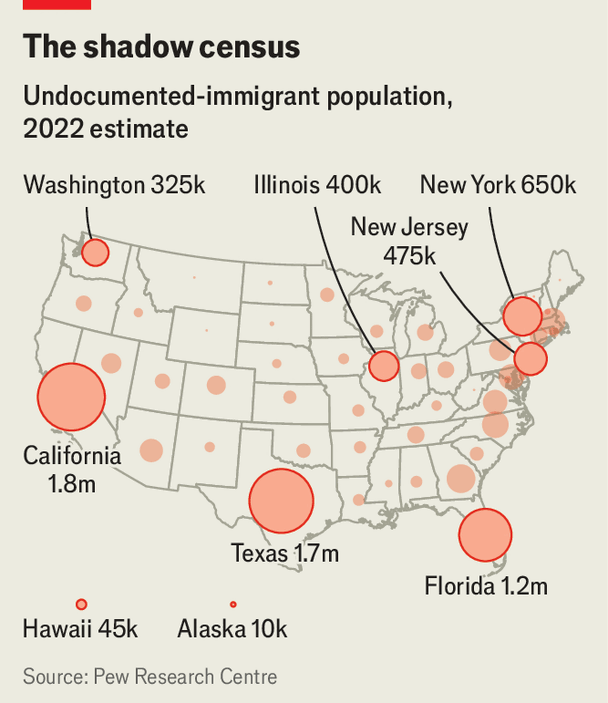

Map: The Economist

Now more is at stake than their approval numbers. In a speech on June 10th Mr Newsom warned other states that “California may be first but it clearly will not end here.” Legal scholars point out that the proclamation federalising National Guard troops did not mention LA, leaving open the possibility of sending them to other cities. After California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois are the Democratic-run states where the most unauthorised immigrants live (see map). Anti-ICE protests have already started to spread beyond Los Angeles, to Chicago, New York City and elsewhere. Some Democratic mayors may see the trouble LA is in and try to avoid attracting Mr Trump’s ire. Daniel Lurie, San Francisco’s moderate mayor, seems to be trying this route, though protesters there have taken to the streets anyway.

What the federal government does next will depend on whether Mr Trump’s end goal is to scare cities into not protesting against deportations, or to provoke unrest so he has an excuse to declare an insurrection and use the military to crack down on places that disagree with him. LA’s experience suggests the latter is not hyperbole. During his speech Mr Newsom coined a clunky phrase: “the rule of Don” (rather than the rule of law). He meant it as an insult, but Mr Trump may not mind. When asked what the standard would be for sending troops elsewhere, the president replied: “The bar is what I think it is.”■

The Americas | Crime and justice

A Harvard man turned narco-gang-buster

Daniel Noboa assures The Economist he can save Ecuador without hurting democracy

Illustration: Fede Yankelevich

Jun 12th 2025|GUAYAQUIL

Listen to this story

The president loves jogging. Yet so determined are gangsters to kill Daniel Noboa that his runs require a military operation. As his motorcade of black SUVs and outriders sweeps back to his apartment after a morning run in Guayaquil, Ecuador’s biggest city, a swarm of heavily armed soldiers surrounds him. Mr Noboa and his wife, incongruous in colourful lycra, slip swiftly inside. “We’ve had death threats on a daily basis for two years,” he tells The Economist, matter-of-factly.

Ecuador is deep in the bloody grip of transnational criminal gangs with links to Mexico, Colombia and Albania. They ship thousands of tons of cocaine, mostly made in Colombia, out of the country to Europe and the United States. Illegal mining and extortion bring in stacks more cash. Other Latin American countries have balked at taking on the gangs. Mr Noboa was recently re-elected on the promise to do just that. His efforts to make Ecuador safe again pose a crucial test that is about more than just one country: is it possible to beat back the rampant transnational gangs while respecting the rule of law and democracy?

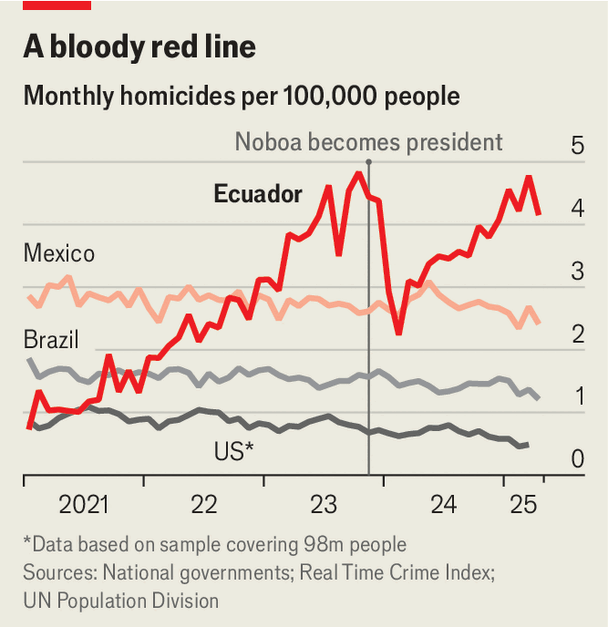

Ecuador’s descent into chaos has been shocking. In 2019 the murder rate was below seven per 100,000, similar to that of the United States. By 2023 it had surged to 45, making it the most violent country in mainland Latin America. The violence followed cocaine-export routes, which shifted to Ecuador to escape increased security at Colombian ports. Ecuador’s vast banana exports offered an ideal smuggling route, its dollarised economy a perfect conduit for laundering cash. Mr Noboa says gangs are moving about $30bn-worth of drugs through Ecuador every year, equivalent to a quarter of the country’s GDP. (Other estimates are smaller.)

Posting through it

The man Ecuadorians have chosen to fight this storm is a curious mixture. Born in Miami, Mr Noboa is the son of a billionaire banana magnate who unsuccessfully ran for president of Ecuador five times. His social-media posts alternate between pictures posed with seized loot and cowed bad guys, and clips of him working out with his influencer wife: a crime-fighting Camelot for the TikTok age.

In light of this, you might expect Mr Noboa to combine charm with the thinly veiled arrogance of privilege and chest-thumping alt-right machismo. Instead, the graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government appears introverted, nervous and wonkish. He is keen to discuss Ecuador’s debt-to-GDP ratio and country-risk premium. He admits to doubts. “There are moments that you start questioning it,” he says when asked if the job is worth the risk. “Most of the time it feels right.”

Mr Noboa was first elected president in October 2023 after the government of a conservative president, Guillermo Lasso, fell apart, prompting a snap election. Mr Noboa’s political experience was a short stint in the National Assembly. At just 35 years old, he was the youngest president ever elected in Latin America. Since then he has pushed legal limits to combat crime, governing through a series of states of exception and using his expanded powers to send the army onto the streets and into prisons. After gangs rioted in prisons and attacked journalists live on television in January 2024, he declared a state of “internal armed conflict”. He is building mega-prisons and has designated 22 gangs as “terrorist organisations”.

After winning re-election in April, Mr Noboa is stepping up the crackdown. He is taking advice from Erik Prince, founder of Blackwater, a controversial mercenary group. Mr Noboa wants to bring in foreign troops, mentioning Israel and the United Arab Emirates. Mr Lasso says all this is “a bit of the pageantry of populism—like, ‘Look, I’m bringing in Iron Man, I’ve got Spider-Man’”. More serious is a new law that allows for drop-of-a-hat raids and asset seizures, increases sentences for organised-crime offences and gives the president greater discretion to declare an internal armed conflict. It reduces the powers of the Constitutional Court, which has blocked some state-of-emergency moves.

Chart: The Economist

So far, results have been underwhelming. Homicides fell by about 15% from 2023 to 2024, but have since surged, especially on the coast. The first months of 2025 were among the bloodiest on record (see chart). Beatriz García Nice, a policy analyst in Guayaquil, suggests Mr Noboa has weakened the gangs, prompting them to lash out in a last-ditch show of force. It is also possible his policy has broken up larger groups, spurring increased violence in the process. “The groups adapt, wars are not linear,” says Mr Noboa.

The militarisation of law enforcement often comes with human-rights violations, for instance when four boys from Guayaquil were found dead near a military base in December after being seized by soldiers. Mr Noboa concedes there are risks to militarisation, but vows to prosecute soldiers who commit abuses. His new law, however, gives him more power to pardon them.

Youthful and social-media-savvy, he is often compared to El Salvador’s president, Nayib Bukele, who has smashed local gangs with mass incarceration. Mr Noboa says he respects Mr Bukele, but laughs off the comparison as absurd. “We’re looking to promote public health and strengthen public education, so ideologically it’s a bit different, I would say, from Bukele.” Instead he compares himself to the presidents of France and Brazil, Emmanuel Macron and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. He expounds on the need to invest in education and create jobs for young men who are vulnerable to gang recruitment.

Mr Noboa recognises that crushing transnational gangs requires cross-border collaboration. He is right, but his execution has so far been woeful. Last year he broke international law by ordering a raid on Mexico’s embassy to arrest a leftist former vice-president, Jorge Glas, who was sheltering there after a conviction for corruption. Any dialogue with Mexico now runs through Switzerland, admits Gabriela Sommerfeld, Ecuador’s foreign minister. That is a huge problem. Mr Noboa concedes as much, but claims collaboration is anyway difficult, seeing that Mexico is “not going to confront narcos”. He also struggles to work with President Gustavo Petro of Colombia who is pursuing “total peace” with his country’s gangs and armed groups, and has a resurgence of political violence to show for it.

No Trump card

Instead he is cleaving to President Donald Trump for help. That is sensible enough, but Mr Trump’s America-first agenda means he is unlikely to send troops or reopen a military base in Ecuador. Mr Noboa is eager to change the constitution to permit such a course. Asked about security help from China, he does not rule it out.

Another problem is that many institutions are either weak or compromised, from the justice system to the electoral authority, anti-money-laundering bodies and political parties. Judges and prosecutors, especially those in remote areas who inevitably handle cases relating to organised crime, lack adequate physical protection. At least 15 have been killed since 2022. Between 2020 and 2022 there were just three convictions for money-laundering.

A strong, independent attorney-general will be crucial. Diana Salazar finished her six-year term in May, having led courageous prosecutions against gangsters and corrupt politicians. Worryingly, both groups will probably try to influence the selection of her successor, as well as that of judges. That could grant criminals dangerous impunity. It helps at least that Mr Noboa wants to speed up justice and vows to “follow the money”.

He is in a strong position to carry out his plans. The leftist opposition is in disarray, his allies dominate the National Assembly and the courts will probably be wary of ruling against him, says Aparicio Caicedo, a former adviser to Mr Lasso. Some, however, fear that his security crackdowns and his eagerness to reform the constitution could see him turn authoritarian.

Mr Noboa is quick to reject this idea. “I won’t stay one second more than what the constitution allows me. I will never ignore the importance of a parliament or the judicial branch, and I cannot go against the Constitutional Court,” he says. “That is what keeps this country civilised.” ■

The Americas | Controlling coca

Bolivia wants the world to stop treating coca leaves like drugs

The WHO is reviewing whether the crop should be removed from international drug-control schedules

Seizing a Schedule I substancePhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025|Cochabamba, Bolivia

Listen to this story

If New York runs on coffee, Cochabamba runs on coca. The leaves—which can be chewed as a mild stimulant, but also processed into cocaine—are everywhere: spread out by the road to dry; sold in bags alongside sweets and SIM cards; stuffed in cheeks as golf-ball-sized bolos. “With a bolo I can drive all night,” boasts one trucker, with a flash of leaf-flecked teeth.

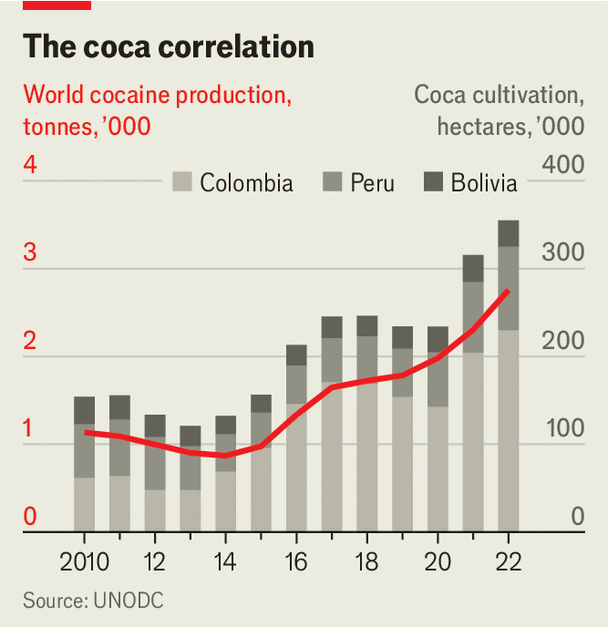

Bolivia is one of very few countries with a legal market for coca. In the rest of the world it is controlled with the same stringency as cocaine and heroin. The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treaty adopted by the United Nations in 1961, lists coca leaf as a “Schedule I” substance, one considered to come with a high risk of abuse and to pose a serious public health threat. Some consider that to be a historic mistake. It might soon change. A review by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which will conclude in October, may recommend that coca be bumped down to Schedule II, or removed from the schedules altogether. The latter would be a first. The prospect is causing hope and anxiety in equal measure.

Andeans have chewed coca for millennia. The Spanish noticed that it kept workers going in the silver mines of Potosí, but saw it as an indigenous vice. Such attitudes persisted well into the 20th century, when the WHO described coca chewing as a “social evil”. When the cocaine business took off, coca’s status as an internationally controlled substance was cemented.

Bolivia never seriously tried to abolish traditional uses of the coca leaf. Like Peru and Colombia, the other main coca-growing countries, it created broad exemptions under national law. Then, in 2013, it negotiated a partial opt-out from the convention. Now it wants coca taken off the drug schedules altogether; it was Bolivia that requested the WHO review. Other treaty articles mean coca would still be controlled to prevent it being used for making cocaine. But de-scheduling would make it easier to develop coca-based products and sell them abroad. Proponents hope it would be a boon for rural development.

Bolivia already has a lively coca economy. The law allows 22,000 hectares of coca fields to feed the legal market. And Bolivians have cooked up new ways to consume coca. In one garage factory, a woman sprinkles leaves with caffeine and fruity flavourings and puts it under a power hammer. The result: coca machucada, an amped-up version of the sacred leaf. Such products have helped win over new consumers, bringing a rural habit to the urban middle class. There is even an “executive bolo”: sachets of ground coca for those anxious about leaves in their teeth.

If coca were de-scheduled, the hope is that the legal international market would boom. Bolivia could start exporting existing products such as coca tea, flour and sweets. But de-scheduling could also boost investment in the leaf. Bolivia’s state-led efforts to industrialise coca for the domestic market failed. But the prospect of a global market could entice investment from companies to create new products, from energy drinks for health nuts to new versions of tipples like Vin Mariani, which mixed Peruvian coca with Bordeaux wine for 19th-century consumers such as Queen Victoria and Pope Leo XIII.

Bolivian coca growers worry that the profits would be gobbled up by international companies. Proponents say the idea would be to legally limit coca cultivation to Bolivia, Peru and Colombia, and to ensure locals benefit from any use of their genetic resources. One template could be the agreement that sees the rooibos tea industry pay a percentage of revenues to indigenous people in South Africa who used the plant before it was industrialised. But Bolivians still worry that industrial-scale coca farming might squeeze them out.

Chart: The Economist

Another fear is that de-scheduling coca would lead to a surge in cultivation that was bound in theory for legal markets, but in practice used to make cocaine. Such diversion already happens with part of Bolivia’s legal production. But while demand for cocaine exists, there will always be an incentive to grow coca for that purpose. And there is evidently no shortage of coca for cocaine under existing laws (see chart). Much would depend on the emergence of new regulatory systems.

If the WHO recommends changing coca’s treaty status, the 53-member UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs will then vote on the question. The diplomatic environment is challenging. The cocaine market is growing, fuelling destructive gangs. Peru opposes de-scheduling. A winning majority would probably need the bloc vote of the European Union, two-thirds of Latin America and the Caribbean, and some unexpected alliances. “It will be tough,” said Andrés López Velasco, a drug-policy expert. “But it’s not impossible.” ■

Middle East & Africa | The kernel of an idea

Globalisation is nuts

A brave and high-tech attempt to export nuts

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025|BOUAKÉ

Listen to this story

The lowly cashew is globalisation in a nutshell. The route from cashew tree to tasty snack follows a peripatetic journey. More than half of the world’s cashew nuts are grown in African countries. Most are exported raw, mainly to Vietnam, for shelling and sorting, before being exported again as processed kernels. Often the nuts munched by Americans or Europeans have travelled more than 20,000km.

African countries lament being the bottom link in global supply chains for cashews and other commodities. A rule of thumb in agro-processing is that just 10-15% of the cost of the final product, say a bag of roasted cashews, goes to the farmer in the country of origin. If more processing is done in Africa, goes the logic, the continent will create jobs and capture more of the $8bn cashew market.

This is why African countries—most of which export predominantly unprocessed commodities—are studying the parable of the Ivorian cashew. Fifteen years ago Ivory Coast, the world’s largest grower of cashews, exported nearly all of its crop as raw nuts. But last year about 30% of its harvest was processed at home; the government aims to increase that to 50% by 2030. Its efforts hold lessons for those who feel Africa gets a raw deal from its raw materials.

After Ivory Coast’s civil war ended in 2011 the government made it a priority to do more processing. The timing was fortuitous. In the 2000s Vietnam supplanted India as the global hub for turning raw nuts into kernels. It did this by mechanising tasks once done by nimble hands—cutting, shelling and peeling. This reduced the cost of processing from about $600 per tonne to $200. Factories that employed 3,000 people in India had 400 in Vietnam. This made businesses consider using the same technology, but closer to where the nuts are grown and eaten.

The Ivorian government, seeing an opening, introduced incentives for domestic and foreign-owned processors. Firms pay no import duties on machinery. They receive a subsidy of about $700 per tonne of processed kernels exported, or 10% of the price paid by the buyer. A regulator was given clout and staffed by competent technocrats. There was consistent high-level support, including from Alassane Ouattara, the president, and his late prime minister, Amadou Gon Coulibaly.

Foreign expertise has been critical. “Agro-processing in theory sounds simple, but it is very technical. It’s food science and business mixed together,” notes Jonathan Said of AGRA, an NGO headquartered in Nairobi. Ivory Coast convinced Olam, a Singaporean firm, to build the first big factories. Several foreign firms have followed.

One is Cashew Coast, which was set up by Mauritians but has investors from all over. Visitors to its factory in Bouaké, a city in central Ivory Coast, are given headphones to block the deafening noise from the machines that cook, shell, dry, peel and sort the nuts. Many are high-tech: one scanner uses optical laser technology to spot defects. Software from SAP, a German tech firm, allows the firm to trace the origin of every shipment. Ivorian women deftly peel the last 15% of shells left by the machines, just as efficiently as their Vietnamese peers, reckons the head of operations.

Salma Seetaroo, the CEO of Cashew Coast, says that “Africa is increasingly delivering a greater value equation.” Processing a tonne of cashews at Vietnamese factories remains cheaper than in Ivory Coast, but brands such as hers are competitive. The cashews taste better, she points out, because they are processed at source and not sitting on a ship for months. Freight costs and carbon emissions are lower. European demand for traceable and “sustainable” produce mean buyers are willing to pay a premium. Concerns that Ivorian factories produce too many broken nuts are less relevant these days, as fragments can be turned into lots of products, including vegan “cheese”.

Donald Trump’s trade war will raise the price of cashews for American snackers. But some in Ivory Coast see a potential upside if it ends up with a lower tariff than Vietnam. “The whole tariff thing could give firms reason to relocate some of their operations from Asia to Africa,” hopes an adviser to Mr Ouattara.

Yet Ivory Coast still has work to do before it can say it has cracked the cashew-nut industry. Foreign-owned firms, which account for about 70% of exports, do not need the government’s subsidy to turn a profit. But for Ivorian outfits it can be the difference between survival and bankruptcy. As ever in industrial policy, there is a fine line between supporting a nascent export industry and indulging firms with no hope. In a worrying sign of protectionism, last year the government briefly suspended the export of raw nuts to ensure supply to locally owned factories.

That step also reflected a deeper problem: the need to guarantee a long-term supply of raw nuts. Farmers’ yields are low compared with those in countries like Cambodia, which has large plantations. In Ivory Coast, as in most of Africa, cashew farmers are smallholders. “There is no such thing as a cashew farmer,” notes Jim Fitzpatrick, a cashew-nut expert: “There are farmers with some cashew trees.” Shoddy storage leads to too much waste. Only a few firms, including Cashew Coast, try to improve farmers’ productivity.

At a village an hour’s drive from Bouaké one farmer says he earned the equivalent of $700 from cashews last year. Will he invest the money in his plot? “I want a motorbike,” he replies. “That way I can take my daughter to look for work at a factory.” These days that is not a nutty idea. ■

Europe | Sunshine in the Valley

Picasso’s home town is thriving

But will Málaga fall victim to its own success?

The sixth cityPhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 12th 2025|MÁLAGA

Listen to this story

ON A RAINY weekday in early spring Málaga is thronged with tourists, clambering over the Moorish castle that overlooks the port, carousing at the pavement bars or queuing for one of half-a-dozen art museums. It wasn’t always thus. Until the turn of the century tourists heading for the resorts of the Costa del Sol shunned what was then a drab former industrial town. Today Málaga, Spain’s sixth city, is booming, powered not just by tourism but also by a burgeoning tech industry. Its economy has outpaced the rest of the Andalucía region for most of the past decade. It is held up by some as a model for other Spanish cities, but some locals fear it may fall victim to its own success.

Its revival began with the pedestrianisation of the centre and the opening in 2003 of a museum dedicated to Pablo Picasso, who was born in the city. Three others followed, including an outpost of Paris’s Pompidou Centre. Though cultural tourism accounts for only a minority of the 14.4m visitors last year to Málaga province (which includes Marbella and other resorts), the museums have helped turn the city into a magnet for tech workers and others. Antonio Banderas, an actor, has returned to his native city to open a theatre.

In a nearby valley sprawl the anonymous buildings of the Technological Park of Andalucía. Founded in 1992 as a joint venture between the city and regional governments and a local bank, it now employs 28,000 workers and houses companies ranging from Accenture and Ericsson to startups. Google and Vodafone have operations in the city. The park is still expanding: it now focuses on cybersecurity, games and microelectronics.

Málaga has natural advantages, says Francisco de la Torre, its mayor. They start with a benign climate and its site on the Mediterranean. It has Spain’s fourth-biggest airport. But it also has good vocational-training centres and a steady, consensual leadership: Mr de la Torre, who is 82, has been mayor since 2000.

Two clouds have darkened the horizon. Like many other Spanish cities, Málaga is short of housing. Some 9,000 new homes are under way, with the city providing the land for private builders. The other worry is the excesses of mass tourism. The historic centre has around 6,000 tourist flats, the highest density in Spain. Carlos Carrera of the local residents’ association complains of “strangers entering buildings, fights, drunks and hooligans in the lift” and of bars that stay open till 2am. “The balance has been upset,” he says. Mr de la Torre replies that the city has banned new tourist flats and is closing those without permits. The overall number is falling, he says.

These are the problems of success. “It was a city in black and white and now it’s in colour,” argues José María Luna, the city’s culture boss from 2011 to 2024. “Málaga has found a place in the world.” ■

Britain | Bagehot

Welcome to Bonnie Blue’s Britain

A place of sin, spin and soft power

Illustration: Nate Kitch

Jun 11th 2025

Listen to this story

Bonnie Blue is the most famous British woman not everyone knows. Ms Blue, a 26-year-old from Nottinghamshire, has become a mainstay of social media, her blonde hair and blue eyes beaming out from TikTok feeds, Instagram reels and YouTube shorts. Her Wikipedia page gets more traffic than Beyoncé’s, and a little less than Taylor Swift’s, even if some still say “Bonnie who?” when her name is mentioned. She has become a frequent guest on podcasts that enjoy immense listenership, yet create barely a ripple in older media.

Why the disparity? Her fame is not family-friendly. Ms Blue is a porn star, famous for stunts such as claiming to have had sex with 1,057 men in 12 hours. Footage of the event is not erotic. It is by turns surreal and disturbing, like staring at a Hieronymus Bosch painting. Nearly all the men awkwardly queuing wear balaclavas; one man brought his mother. At the end, the final gentleman begins thanking the cameraman and crew before launching into a rendition of “You’ve Got A Friend In Me”, from “Toy Story”.

Luckily, attention rather than arousal was the aim. The video was to plug OnlyFans, a British website where customers can pay porn stars directly. Ms Blue said she earned £600,000 a month posting more orthodox videos than the marathon sessions that made her name. In terms of attracting notice, it worked. When some people picture Britain, they picture Ms Blue.

And why not? Ms Blue’s strengths are Britain’s strengths. Smut, scuzz and sin are fixtures of the British economy. Tobacco companies are among the largest in the ftse 100, along with booze companies. British gambling companies, though considerably smaller, are among the country’s best-run.

OnlyFans is simply another name on the list. In 2023 people spent a little under $7bn in total on OnlyFans—or roughly how much broadcasters paid in total to show the Premier League outside Britain from 2022 to 2025. OnlyFans, which takes a 20% cut, achieves pre-tax profits of nearly $700m, sending a wodge of corporation tax to hm Revenue & Customs. Now OnlyFans’ owner is looking to sell it, wanting $8bn for the company.