The Economist Articles for June. 5th week : June. 29nd(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.06.20조회수126 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for June. 5th week : June. 29nd(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Conflict in the Middle East

Where will the Iran-Israel war end?

In a worse place if Donald Trump rushes in

Jun 19th 2025

Listen to this story

IN THE 20 months since Hamas massacred almost 1,200 people, Israel has fought in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. On June 13th, when Israeli aircraft struck Iran, it became clear that these campaigns waged against Iranian clients and proxies have all been leading to today’s momentous confrontation between the Jewish state and the Islamic Republic.

The Iran-Israel war will reshape the Middle East, just as Arab-Israeli wars did between 1948 and 1973. As President Donald Trump teeters between talking to Iran and sending American aircraft and missiles to bomb it, the question is whether this first Iran-Israel war will also be the last, thereby creating space for a new regional realignment built on economic development. Or will it lead to a series of Iran-Israel wars that mire the Middle East in years, if not decades, of further violence?

Israeli minds are focused on the looming threat of a nuclear-armed Iran. Israel claims that it acted now because Iran has been racing towards a bomb, under the cover of arms talks with America. Western intelligence agencies are less sure. Either way, a nuclear Iran could abuse its neighbours with impunity, much as Vladimir Putin has Ukraine. It could also spark an atomic arms race in the Middle East and beyond.

More on the war between Israel and Iran:

A nuclear-armed Iran would therefore be a disaster for Israel and the world. Mr Trump’s desire to stop it is a welcome signal to would-be proliferators across the planet that they should abandon their ambitions.

However, Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, faces a grave problem. To remove the threat, he must destroy Iran’s wherewithal to make a bomb or he must eliminate its desire to acquire one. War with Iran is unlikely to achieve either of those things. Even if Israel wrecks Iran’s infrastructure, thereby postponing the day when it might complete a weapon, it cannot eradicate the know-how accumulated over decades. And far from eliminating the Iranian regime’s desire to go nuclear, Israeli strikes are likely to redouble it.

Mr Netanyahu’s solution is to encourage Iranians to rise up and topple the Islamic Republic. He calculates that a new regime is likely to be less tyrannical, less bellicose and less wedded to a nuclear programme. But Israel can only create conditions that favour a change of regime; it cannot impose a coup from the skies. Besides, nobody knows how willing a new government would actually be to make peace with Israel or to abandon nuclear dreams which, after all, began with the shah.

The conclusion is that the only thing under Israel’s direct control is to buy time, by setting back Iran’s technical capacity to get a bomb. If, in a few years, Iran renewed its nuclear programme, Israel would have to mount another operation all over again. The barriers to success would surely grow.

What is to be done? The G7, meeting in Canada, called for de-escalation and there are reports that Iran wants to negotiate. Diplomacy, if it worked, would indeed be the best way to solve this problem. In contrast to war, it could both lead to the dismantling of the programme and also, by building confidence, reduce Iran’s incentive to dash for a bomb. That is why Mr Trump’s decision in 2018 to walk out of an imperfect arms agreement with Iran was a terrible blunder.

In practice, however, a deal will be very hard to reach. For it to be credible, Iran must agree to give up every ounce of highly enriched uranium, submit to intrusive inspections and forgo all but a token enrichment capacity. Would the regime in Tehran ever accept such humiliating terms as a precondition? Only, if at all, if it fears for its survival. Perhaps sensing that, Mr Trump has demanded Iran’s “unconditional surrender”, issuing threats that have caused residents to flee Tehran.

The best way to apply pressure to Iran, hawks suggest, would be to leave negotiations for later—and for America instead to shift from merely defending Israel and deterring Iran to joining the attack on Iran’s programme. This has advantages, too. America’s bunker-busting bombs are much more likely than Israel’s to penetrate key nuclear facilities such as Fordow, in central Iran. Iran might talk sooner, because it would know that America has the resources to strike it long after Israel’s stocks of guided munitions start to run out.

Yet for Mr Trump to enter the fray would be a huge gamble. He was elected to keep America out of wars in the Middle East. Even if he intends to hit nuclear targets and nothing else, America could be sucked in. So far Iran has focused all its strike-power on Israel, but it may be saving missiles for a regional assault. It may also have terror cells around the world. Imagine that it now starts to kill American troops and civilians, or that it sends energy prices soaring by blasting Saudi Arabia’s oil industry or blocking the Strait of Hormuz, a vital waterway for oil and gas tankers. Or perhaps it will hit tower blocks in Dubai or Qatar, beginning a stampede of the expatriates who power their economies. Mr Trump would have to retaliate.

Where does that leave America? Fordow is important, but even if it is destroyed Mr Trump cannot be sure of eradicating Iran’s programme once and for all. Secret facilities and stocks of uranium might survive; know-how definitely would. If Iran is not to go nuclear, America might therefore have to go to war in the Middle East repeatedly—forcing it to choose between non-proliferation and giving full attention to its rivalry with China. Sooner or later, America will come to realise that talks offer the least bad path and that the refusal of Mr Netanyahu to countenance them is an obstacle.

Centrifugal forces

So Mr Trump faces a trade-off. By doing more damage than Israel could alone, America could set the clock back further. Its participation might also increase the chances that the regime enters talks in earnest or collapses. But those gains are uncertain and must be weighed against the risk of a regional conflagration. In a shifting landscape, better for the king of ambiguity to wait to see how far Israel’s campaign gets, whether the Iranian regime is willing to talk and to gauge whether American intervention could tip the balance. ■

Leaders | Factory fever

The world must escape the manufacturing delusion

Governments’ obsession with factories is built on myths—and will be self-defeating

Jun 12th 2025

Listen to this story

Around the world, politicians are fixated on factories. President Donald Trump wants to bring home everything from steelmaking to drug production, and is putting up tariff barriers to do so. Britain is considering subsidising manufacturers’ energy bills; Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, is offering incentives for electric-vehicle-makers, adding to a long-running industrial-subsidy scheme. Governments from Germany to Indonesia have flirted with inducements for chip- and battery-makers. However, the global manufacturing push will not succeed. In fact, it is likely to do more harm than good.

Today’s zeal for homegrown manufacturing has many aims. In the West politicians want to revive well-paying factory work and restore the lost glory of their industrial heartlands; poorer countries want to foster development as well as jobs. The war in Ukraine, meanwhile, shows the importance of resilient supply chains, especially for arms and ammunition. Politicians hope that industrial prowess will somehow translate more broadly into national strength. Looming over all this is China’s tremendous manufacturing dominance, which inspires fear and envy in equal measure.

Jobs, growth and resilience are all worthy aims.

Unfortunately, however, the idea that promoting manufacturing is the way to achieve them is misguided. The reason is that it rests on a series of misconceptions about the nature of the modern economy.

One concerns factory jobs. Politicians hope that boosting manufacturing means decent employment for workers without university degrees or, in developing countries, who have migrated from the countryside. But factory work has become highly automated. Globally, it provides 20m, or 6%, fewer jobs than in 2013, even as output has increased 5% by value. For all countries to take more of a shrinking pie is impossible.

Many of the good jobs created by today’s production lines are for technicians and engineers, not lunch-pail Joes. Less than a third of American manufacturing jobs today are production roles carried out by workers without a degree. By one estimate, bringing home enough manufacturing to close America’s trade deficit would create only enough new production jobs to account for an extra 1% of the workforce. Manufacturing no longer pays those without a degree more than other comparable jobs in industries such as construction. As productivity growth is lower in manufacturing than it is in service work, wage growth is likely to be disappointing, too.

Another misconception is that manufacturing is essential for economic growth. India’s manufacturing output, as a share of gdp, languishes about ten percentage points below Mr Modi’s target of 25%. But that has not stopped India’s economy growing at an impressive rate. In the past few years China has struggled to meet its growth targets, even as its manufacturers have come to dominate entire sectors, such as renewable energy and electric vehicles.

What about the argument that, given the war in Ukraine and tensions with China, the rich world must reindustrialise for the sake of national security? It seems dangerous to rely on factories abroad. And covid-19 caused a supply-chain panic. Some dependencies are indeed chokeholds. China’s near-monopoly in refining rare earths has recently allowed it to put the brakes on global carmaking, giving it leverage over America. It is also prudent for the West to build up stocks of weapons and ammunition, to ensure that crucial infrastructure is sourced from allies and to build things with long lead times, like ships, before conflict breaks out.

But in today’s ultra-specialised world, across-the-board subsidies for reindustrialisation will not do much to boost war-readiness. Making Tomahawks is entirely different from making Teslas. Far from suggesting that countries at peace must develop the capacity to make lots of drones, the war in Ukraine shows that a wartime economy can innovate and multiply production volumes remarkably fast.

The final part of the manufacturing delusion is the idea that China’s industrial might is a product of its state-led economy—and so must be countered with a similarly extensive industrial policy everywhere else. China does indeed distort its markets in all kinds of ways, and early in this century it manufactured an unusual amount given its level of development. But those days are past.

China has not escaped the global shrinkage of factory jobs since 2013. The share of its workforce in factories corresponds to America’s at a similar level of prosperity; and it is lower than it was in most other rich economies. China’s 29% share of global manufacturing value-added is a function of its size rather than its strategy. After years of fast growth, it now has an enormous domestic market to support its manufacturers. Innovation is begetting innovation; a “low-altitude economy” of drones and flying taxis promises to take flight soon. Yet, even though China’s goods exports have grown by 70% relative to global GDP since 2006, they have fallen by half as a share of the Chinese economy.

Factory settings

The way to rival the manufacturing heft of China is not through painful decoupling from its economy, but by ensuring that a sufficiently large bloc rivals it in size. This is best achieved if allies are able to work together and trade in an open and lightly regulated economy; factories in America, Germany, Japan and South Korea together add more value than those in China. As the pandemic showed, diverse supply chains are a lot more resilient than national ones.

Alas, governments today are heading in precisely the opposite direction. The manufacturing delusion is drawing countries into protecting domestic industry and competing for jobs that no longer exist. That will only lower wages, worsen productivity and blunt the incentive to innovate, while leaving China unrivalled in its industrial might. The mania for manufacturing is not just misguided. It is self-defeating. ■

Leaders | Phew, it’s a girl!

The stunning decline of the preference for having boys

Millions of girls were aborted for being girls. Now parents often lean towards them

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

Without fanfare, something remarkable has happened. The noxious practice of aborting girls simply for being girls has become dramatically less common. It first became widespread in the late 1980s, as cheap ultrasound machines made it easy to determine the sex of a fetus. Parents who were desperate for a boy but did not want a large family—or, in China, were not allowed one—started routinely terminating females. Globally, among babies born in 2000, a staggering 1.6m girls were missing from the number you would expect, given the natural sex ratio at birth. This year that number is likely to be 200,000—and it is still falling.

The fading of boy preference in regions where it was strongest has been astonishingly rapid. The natural ratio is about 105 boy babies for every 100 girls; because boys are slightly more likely to die young, this leads to rough parity at reproductive age. The sex ratio at birth, once wildly skewed across Asia, has become more even. In China it fell from a peak of 117.8 boys per 100 girls in 2006 to 109.8 last year, and in India from 109.6 in 2010 to 106.8. In South Korea it is now completely back to normal, having been a shocking 115.7 in 1990.

In 2010 an Economist cover called the mass abortion of girls “gendercide”. The global decline of this scourge is a blessing. First, it implies an ebbing of the traditions that underpinned it: the stark belief that men matter more and the expectation in some cultures that a daughter will grow up to serve her husband’s family, so parents need a son to look after them in old age. Such sexist ideas have not vanished, but evidence that they are fading is welcome.

Second, it heralds an easing of the harms caused by surplus men. Sex-selective abortion doomed millions of males to lifelong bachelorhood. Many of these “bare branches”, as they are known in China, resented it intensely. And their fury was socially destabilising, since young, frustrated bachelors are more prone to violence. One study of six Asian countries found that warped sex ratios led to an increase of rape in all of them. Others linked the imbalance to a rise in violent crime in China, along with authoritarian policing to quell it, and to a heightened risk of civil strife or even war in other countries. The fading of boy preference will make much of the world safer.

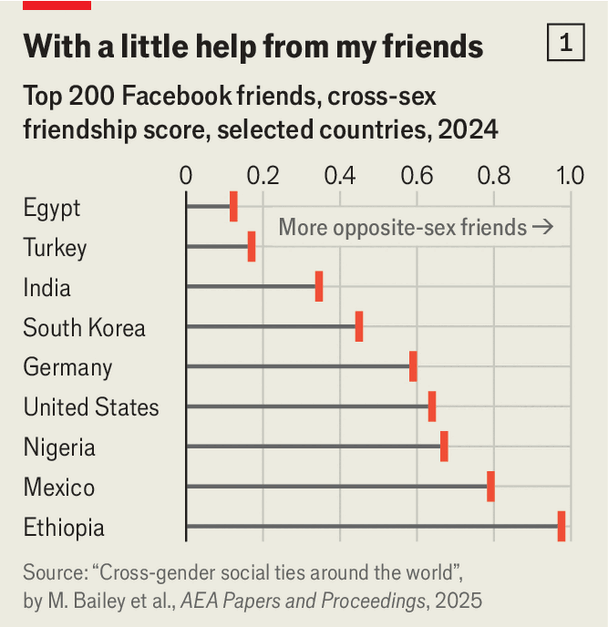

In some regions, meanwhile, a new preference is emerging: for girls. It is far milder. Parents are not aborting boys for being boys. No big country yet has a noticeable surplus of girls. Rather, girl preference can be seen in other measures, such as polls and fertility patterns. Among Japanese couples who want only one child, girls are strongly preferred. Across the world, parents typically want a mix. But in America and Scandinavia couples are likelier to have more children if their early ones are male, suggesting that more keep trying for a girl than do so for a boy. When seeking to adopt, couples pay extra for a girl. When undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and other sex-selection methods in countries where it is legal to choose the sex of the embryo, women increasingly opt for daughters.

People prefer girls for all sorts of reasons. Some think they will be easier to bring up, or cherish what they see as feminine traits. In some countries they may assume that looking after elderly parents is a daughter’s job.

However, the new girl preference also reflects increasing worries about boys’ prospects. Boys have always been more likely to get into trouble: globally, 93% of jailbirds are male. In much of the world they have also fallen behind girls academically. In rich countries 54% of young women have a tertiary degree, compared with 41% of young men. Men are still over-represented at the top, in boardrooms, but also at the bottom, angrily shutting themselves in their bedrooms.

Governments are rightly concerned about boys’ problems. Because boys mature later than girls, there is a case for holding them back a year at school. More male teachers, especially at primary school, where there are hardly any, might give them role models. Better vocational training might nudge them into jobs that men have long avoided, such as nursing. Tailoring policies to help struggling boys need not mean disadvantaging girls, any more than prescribing glasses for someone with bad eyesight hurts those with 20/20 vision.

In the future, technology will offer parents more options. Some will be relatively uncontroversial: when it is possible to tweak genes to avoid horrific hereditary diseases, those who can will not hesitate to do so. But what if new technologies for sex selection become widespread? Couples undergoing fertility treatment can already choose sperm with X chromosomes or determine an embryo’s sex via genetic testing. Such techniques are expensive and rare, but will surely get cheaper.

Also, and more important, more parents who conceive children the old-fashioned way are likely to use cheap, blood-based screening in the first weeks of pregnancy to find out about genetic traits. These tests can already reveal the sex of the embryo. Some people trying for a girl may then use pill-based abortifacients to avoid having a boy. As a liberal newspaper, The Economist would prefer not to tell people what kind of family they should have. Nonetheless, it is worth pondering what the consequences might be if a new imbalance were to arise: a future generation with substantially more women than men.

The power of numbers

It would not be as bad as too many men. A surplus of single women is unlikely to become physically abusive. Indeed, you might speculate that a mostly female world would be more peaceful and better run. But if women were ever to make up a large majority, some men might exploit their stronger bargaining position in the mating market by becoming more promiscuous or reluctant to commit themselves to a relationship. For many heterosexual women, this would make dating harder. Some wanting to couple up would be unable to do so.

Celebrate the cooling of the war on baby girls, therefore, and urge on the day when it ends entirely. But do not assume that what comes next will be simple or trouble-free. ■

Business | Schumpeter

AI agents are turning Salesforce and SAP into rivals

Artificial intelligence is blurring the distinction between front office and back office

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jun 5th 2025

Listen to this story

ENTERPRISE SOFTWARE is an unlikely source of hubbub. Bringing up CRM or ERP in conversation has usually been a reliable way to be left alone. But not these days, especially if you are chatting to a tech investor. Mention the acronyms—for customer-relationship management, which automates front-office tasks like dealing with clients, and enterprise resource planning, which does the same for back-office processes such as managing a firm’s finances or supply chains—and you will set pulses racing.

Between June and early December 2024 Salesforce, the 26-year-old global CRM giant, created more than $120bn in shareholder value, lifting its market capitalisation to a record $352bn. In the past 12 months SAP, a German tech titan which more or less invented ERP in the 1970s, has generated more. It is Europe’s most valuable company, worth $380bn, likewise an all-time high. Both enterprise champions rank among the world’s top ten software companies by value. Maybe not so dull, after all?

The source of the excitement is another, much sexier acronym: AI. Builders of clever artificial-intelligence models may get all the attention; this week Elon Musk’s xAI hogged the headlines when it was reported that the startup was launching a $300m share sale that would value it at $113bn. But if the technology is to be as revolutionary as boosters claim, it will in the first instance be because businesses use it to radically improve productivity. And as anyone who has tried—and probably failed—to replace corporate computer systems will tell you, they are likely to do so with the assistance of their current IT vendors.

Salesforce and SAP each believes it will be the one ushering its clients into the AI age. The trouble is that many of those clients use both firms’ products. Perhaps nine in ten Fortune 500 firms run Salesforce software. The same share relies on SAP.

This did not matter when the duo focused on their respective bread and butter. A client would run Salesforce’s second-to-none CRM in the front office and SAP’s first-rate ERP in the back. Amazon and Walmart, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, BMW and Toyota: pick a household name and the odds are it does just that.

A big reason for SAP and Salesforce to slather a thick layer of AI on top of their existing offering, though, is to give customers a way to uncurdle their data, analyse it and, with the help of semi-autonomous AI agents interacting with one another on behalf of their human managers, act on it. In this newly blended world, the lines between front and back office are fudged. “It’s one user experience,” sums up Irfan Khan, SAP’s data-and-analytics chief.

Controlling the user interface for this “agentic” AI experience promises fat profits. It also creates a head-to-head rivalry between the two enterprise masterchefs. For their AI recipes look alike.

Step one: expand your range of products. SAP has improved its front-office chops by buying CRM firms (like CallidusCloud) and marketing platforms (such as Emarsys). Though Salesforce has not gone full-ERP, it has a 16-year-old partnership with Certinia, whose financial-management system sits exclusively atop its platform. It has bought firms like ClickSoftware, which helps businesses manage their service workforce. On June 2nd it hired the team behind MoonHub, a recruitment-and-HR startup. Clients, spared from switching between providers for every specialist function, love it. So do SAP and Salesforce, since it amasses more client data, AI’s great leavener, in their own systems.

Step two: piggyback on the “hyperscalers”. This allows clients to choose between the cloud giants, including, in China, Alibaba and Tencent (and, in Salesforce’s case, excluding Microsoft, with which its co-founder and boss, Marc Benioff, has a long-running feud). It saves SAP and Salesforce from splurging on what each sees as infrastructure destined for “commoditisation”. Oracle, the giant of corporate-database management which has taken the opposite approach, has seen its quarterly capital budget explode from $400m in 2020 to nearly $6bn in its latest quarter; SAP and Salesforce spend $300m-400m a quarter between them.

Step three: whip up the AI layer. In February SAP teamed up with Databricks, a $60bn AI startup, to help clients make sense of their information, including that stored outside SAP systems, and deploy SAP’s Joule AI agents across their operations. On May 27th Salesforce said it would pay $8bn for Informatica, which designs tools to integrate and crunch corporate data. This will make its own Agentforce easier for clients to use beyond the front office.

Right now investors prefer what SAP is serving up. Its systems cover a wider range of functions and thus contain more data. This data is also notoriously hard for non-SAP systems to extract. As annoying as this may be for clients, it gives them an incentive to look from inside the SAP platform out rather than the other way round. SAP’s share price has risen by 12% in the past six months.

Meanwhile, Salesforce’s has collapsed like a bad soufflé. It is down by nearly 30% since its peak in early December. Although its sales passed those of SAP in 2023, growth is slowing while SAP’s accelerates. Analysts wonder if Agentforce, the launch of which fuelled last year’s rally, can make real money. They also fear a return to profligate dealmaking that culminated with the $28bn purchase in 2021 of Slack, a corporate-messaging platform.

Too many cooks

Investors could yet sour on SAP just as they have on Salesforce. Gartner, a research firm, reckons that between 2020 and 2024 rivals like Workday cut its share of the ERP business from 21% to 14%. For all its front-office efforts, its CRM sales declined around that time, even as Salesforce preserved its 20% slice of a growing market. Microsoft, which has its own cloud, its own cutting-edge AI and plenty of business clients, is elbowing its way into ERP, as well as CRM. The enterprise-AI food fight is just beginning. ■

Business | Schumpeter

Make America French Again

Gallic lessons for the American private sector

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jun 12th 2025

Listen to this story

ON JUNE 14TH Constitution Avenue will turn into the Champs Elysées for a day. Some 150 military vehicles, 50 aircraft and 6,600 troops will roll, fly and march past the White House to celebrate the US Army’s 250th birthday (and, coincidentally, its current occupant’s 79th). The scene will be reminiscent of the annual Bastille Day parade in Paris, which so inspired Donald Trump when he attended one during his first presidential term that he has since insisted on emulating it at home.

The Pentagon pantomime is not Mr Trump’s only recent French import. The Oval Office got a Versailles-style gilded makeover. And even as they turn their noses up at goods from France and the rest of the European Union, which may soon face a 50% tariff, the president and people around him are turning into avid consumers of French ideas. These include what by America’s free-market standards counts as a heavy dose of dirigisme.

In recent months the Trump administration has touted not just tariffs (to protect domestic industry) but also national champions (such as the $500bn Stargate artificial-intelligence project), price controls (for pharmaceuticals) and state ownership (demanding a golden share in return for blessing a Japanese takeover of US Steel). On June 5th Steve Bannon, a prominent MAGA-whisperer, went so far as to call for the full nationalisation of SpaceX, a rocketry-and-satellite firm belonging to Elon Musk, a former “First Buddy” who had just had an epic falling-out with the president.

Mr Trump himself has yet to channel his inner François Mitterrand in so far as seizing private assets is concerned. But it is becoming clear that for large sections of his right-wing movement, Making America Great Again involves the sort of protectionism and state meddling that would be more familiar to Mitterrand than to his American contemporary, Ronald Reagan.

Chief executives in industries that could benefit from protection have cheered parts of this agenda. Mary Barra of General Motors has defended Mr Trump’s tariffs on cars as helping “level the playing-field” warped by other countries’ unfair rules. Leon Topalian of Nucor said those on steel, of which his firm is America’s biggest producer, were “long overdue”. Marc Bitzer of Whirlpool has described the washing-machine maker as a “net winner” from Trumpian trade policies. However, for most American CEOs it all seems about as appealing as a corked Pétrus.

To understand their sniffiness, consider American business before Reagan’s free-market revolution. The 1960s seem to be the time when, in populist MAGA eyes, America was great: men were men, most women had yet to discover feminism and businesses built stuff. Manufacturing accounted for more than a fifth of total output. Effective tariffs averaged 5-10%. Unions enjoyed plenty of clout. By 1970 more than half of the net value generated by non-financial companies was paid out to workers as wages, twice the share that flowed to their employers’ bottom lines. In all these respects, America Inc and France SA were hard to tell apart.

American capitalists look back at the period of Franco-American similitude with less nostalgia. Between 1960 and 1980 their companies turned profits (as measured by the gross operating surplus of non-financial firms) amounting to a ho-hum 14% of GDP. Uncle Sam pocketed around a third of that in corporation tax. Rising inflation,exacerbated by Richard Nixon’s 90-day freeze on prices and wages in 1971, pushed up short-term interest rates. The cost of capital for a typical firm soared from 7.5% or thereabouts in the 1960s to nearly 15% in the early 1980s. In the two decades to the start of 1980 the S&P 500 index of large companies rose by 80%, for a paltry compound annual return of 3%.

Both in terms of profitability and stockmarket returns, the pre-Reagan era in America also happens to mirror the past 20 disappointing years in corporate France. Since 2005 French companies’ gross operating surplus has hovered around 15-16% of GDP and the CAC 40 index of the largest ones has returned a piddling 3.5% a year. The ten blue-chip businesses part-owned by the state have done even worse. They include makers of aeroplanes (Airbus, Safran), arms (Thales), cars (Renault, Stellantis) and materials (Saint-Gobain), utilities (Engie, Veolia), plus a bank (Société Générale) and a telecoms operator (Orange). As a group, they represent 21% of the index’s market capitalisation—and generated no shareholder value in the 20 years to January 2025.

Meanwhile, American business has zoomed ahead. Its profits rose from less than 15% of GDP in 2003 to around 18.5% in the early 2020s. Since the start of 2005 the S&P 500 has ballooned five-fold, yielding a compound return of 8.2% a year. Three American technology giants, Microsoft, Nvidia and Apple, are worth more apiece than the entire CAC 40. France’s most valuable firm, Hermès, a $280bn manufacturer of pricey bags and scarves, wouldn’t make America’s top 25.

France is not as étatiste as it was. But the state remains meddlesome. In 2023 it strong-armed grocers to freeze prices of hundreds of everyday food items. Dealing with its representatives on corporate boards is impossible, says an executive with experience of the ordeal. Even when it does not own a stake, it can interfere—as it did in 2005 by blocking PepsiCo’s takeover of Danone, a French yogurt-maker that the government could not bear to see swallowed by an American rival.

Au revoir, laissez-faire?

Mr Trump’s views on the strategic importance of dairy products are unknown. He has ignored Mr Bannon’s SpaceX suggestion. He is a tax-cutter at heart (even if it means exploding debt). And his administration appears too undisciplined to enact French-style five-year economic plans. Still, American bosses are right to be on alert for more soupçons of Mr Trump’s unlikely Francophilia. ■

Asia | From shrimp to dolphin

Can South Korea’s new president get his country back on track?

From culture to chips to arms, South Korea should punch above its weight

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 19th 2025|Seoul

Listen to this story

UNTIL RECENTLY South Korea seemed to be moving inexorably up the global food chain. Gone are the days of a “shrimp among whales”, as a traditional proverb described the nation’s position beside larger neighbours. Today’s South Korea is relatively free, relatively rich and relatively large, part of a small club of democratic nations with a GDP per person over $30,000 and a population over 50m (see chart). As Lee Jae-myung, the newly elected president of South Korea, quipped in an interview with The Economist earlier this year, now it is more fitting to compare his country to a dolphin.

But that progress was thrown into question last December when Yoon Suk Yeol, then South Korea’s president, briefly imposed martial law. Although he was ultimately impeached, the episode raised troubling questions about the health of the country’s democracy, the stability of its economy and the trajectory of its foreign policy. “Our national prestige has fallen,” Mr Lee lamented during the campaign to replace Mr Yoon. South Korean society remains intensely polarised. Other problems loom. The Bank of Korea recently cut this year’s GDP-growth forecast by half, to just 0.8%. Donald Trump’s tariffs threaten South Korea’s economy; in the past he has also cast doubt on America’s security commitments to South Korea and has appeared to placate North Korea’s dictator. Can Mr Lee sort out his country?

Chart: The Economist

Three industries underpin South Korea’s global clout: culture, technology and arms. Start with culture, perhaps the best known export. At a k-pop concert, such as the appearance by Seventeen at Gocheok stadium in Seoul last year, the crowd resembles a mock United Nations, with fans from as far afield as Toronto, Paris and Manila. As Juraimi Jaril, a fan from Singapore, puts it, “K-pop really put Korea on the map.” Last year K-pop groups accounted for four of the ten most commercially successful albums in the world, according to IFPI, an international recording-industry body—and this was a year when the genre’s biggest stars, BTS, were taking a break from music to perform mandatory military service.

Attention has also spread to other forms of culture. “These days we’re eating kimchi instead of cauliflower!” King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands gushed during a reception in South Korea’s honour in 2023, noting the spread of k-drama, k-movies, k-beauty and even k-food. In November Han Kang, a novelist, became the first woman from Asia to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Membership in fan communities connected to hallyu (“Korean wave” culture) has grown from under 10m in 2012 to 225m in 2023; while acolytes are primarily concentrated in Asia, groups of over 1m exist in countries as disparate as Italy, Chile and Jordan.

K-fans’ spirits remained undimmed in the face of political turmoil. South Korea welcomed more than 3.5m foreign tourists between December and February, around 20% more than in the same period of 2023-24. Mr Lee has pledged more state support for the creation and distribution of k-content, through export financing and tax breaks. “Culture is the economy, and culture is international competitiveness,” he declared enthusiastically in his inauguration speech.

A taste for all things Korean has helped whet an appetite for Korean goods and gadgets, too. “It opens customers’ eyes—once you see the dramas you get into the other parts,” says Ryu Jin Roy, chairman of the Federation of Korean Industries, a lobby group for big business. South Korean firms are among the global leaders in consumer goods, from smartphones to cars.

But South Korea’s most strategic products are the least visible. Samsung and SK Hynix, two South Korean electronics behemoths, dominate the market for mainstream memory chips, the commodity of the semiconductor world. The firms have also pioneered a new type of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) technology that is an essential element in chips for generative artificial intelligence (AI), enabling higher performance at smaller sizes and lower power consumption. “HBM is a technology miracle,” Jensen Huang, the chief executive of Nvidia, the AI chip darling, said last year. While trailing Taiwanese firms, South Korea’s champions also produce high-end logic chips. Mr Lee has pledged to assemble a 100trn won ($73bn) public-private fund to continue developing South Korea’s AI and semiconductor infrastructure.

K-defence may be South Korea’s next hit industry. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, South Korea was an exception to the global shortage of munitions. Because of the need to respond to continuing threats from North Korea, “our capacity is still quite high and we are able to surge production,” says Mr Ryu, who also heads Poongsan Group, a big South Korean metals and munitions maker. South Korean arms exports averaged $13bn annually between 2022 and 2024, up from an average of $3bn between 2011 and 2021, putting it among the world’s top ten arms exporters. America hopes to tap South Korean shipbuilders to help revive its dilapidated shipbuilding industry.

South Koreans across the political spectrum share pride in this move up the geopolitical food chain. Yet, as it has grown, South Korea’s surrounding habitat has become ever harsher, leaving little room for manoeuvre, even for the swiftest dolphin. Mr Lee has pledged to pursue a “pragmatic” foreign policy. His aim is to strengthen his country’s alliance with America and reinforce a budding rapprochement with Japan, while repairing relations with China and reopening dialogue with North Korea.

A military kind of music

Mr Lee’s first weeks in office reveal his priorities. His first call went to the White House. Mr Trump and Mr Lee pledged to work towards an agreement on tariffs and trade, and to play a round of golf together. Second was Japan’s prime minister, Ishiba Shigeru, who said he wished to move bilateral relations forward. Then came Xi Jin-ping, China’s leader, whom Mr Lee formally invited to an Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation leaders meeting in South Korea this autumn; if Mr Xi comes, it would be his first visit to the country since 2014. Mr Lee also turned off loudspeakers blasting propaganda into North Korea.

Pulling off the balancing act will be difficult. Mr Trump’s administration is pushing Asian partners to choose sides between America and China more definitively. Last month at the Shangri-La Dialogue, an annual meeting of defence bigwigs in Singapore, Pete Hegseth, America’s defence secretary, warned against “seeking both economic co-operation with China and defence co-operation with the United States”. Steve Bannon, Mr Trump’s former campaign chief and MAGA ideologue, put it far more bluntly to Chosun, a South Korean newspaper. Talk of a pragmatic balance between the superpowers is “full of shit,” he said. “If South Korea believes in freedom and democracy, it cannot claim neutrality between the US and China.”

In the long term, the greatest threats to South Korea’s continued flourishing are domestic. Demographic change is sapping South Korea’s growth prospects; no president has managed to make a meaningful dent in the problem. Last year the total fertility rate rose, slightly, for the first time in nearly a decade—but it remained the lowest in the world, at just 0.75. The population is projected to shrink to 47m by 2050, and to 37m by 2070.

The economy grew an average of 6.4% per year between 1970 and 2022, but the Bank of Korea reckons that even with improvements to productivity, growth will slow to an annual average rate of 2.4% in the 2020s, 0.9% in the 2030s, and 0.2% in the 2040s. A business-as-usual approach means that “K-power will not only peak, but begin to decline rapidly,” writes Lee Chung-min of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, an American think-tank.

The next phase of South Korea’s history, in short, is not about whether it can become a whale, but whether it can continue to thrive as a dolphin. ■

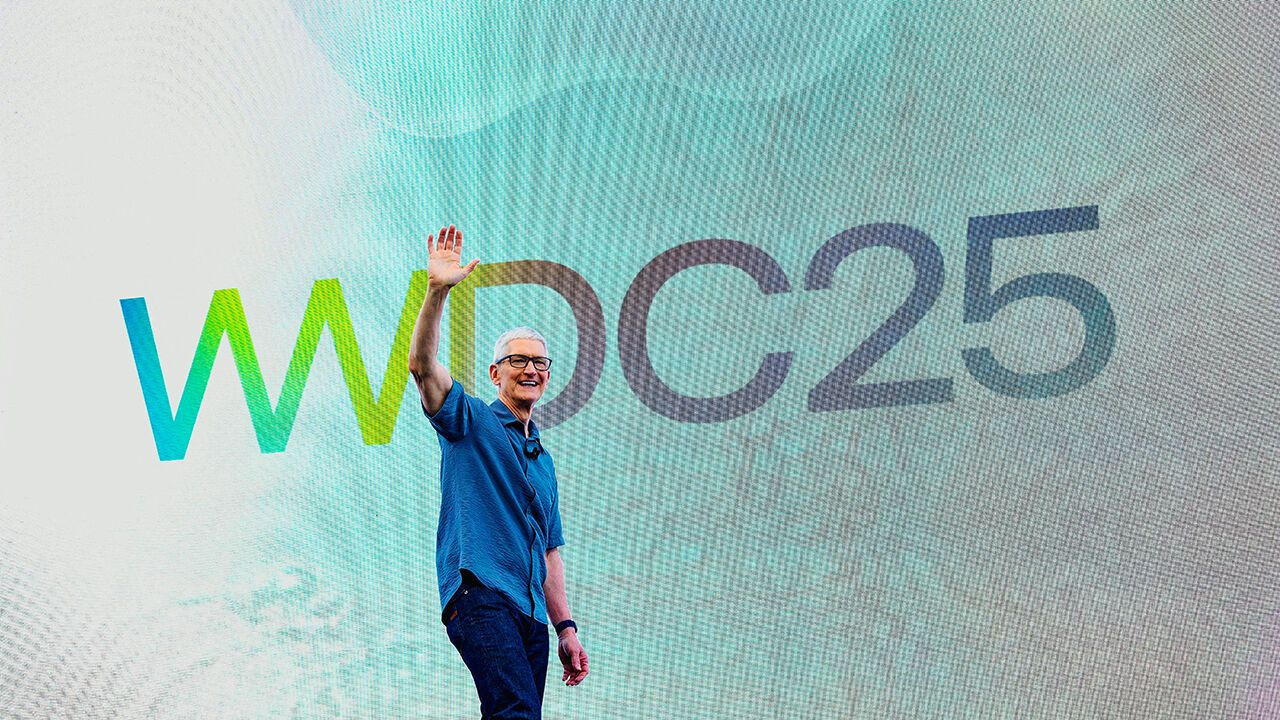

Business | Falling from the sky

Can Tim Cook stop Apple going the same way as Nokia?

It’s time to tear up the rule book

Photograph: Reuters

Jun 8th 2025|SAN FRANCISCO

Listen to this story

Editor’s note (June 9th 2025): This article has been updated.

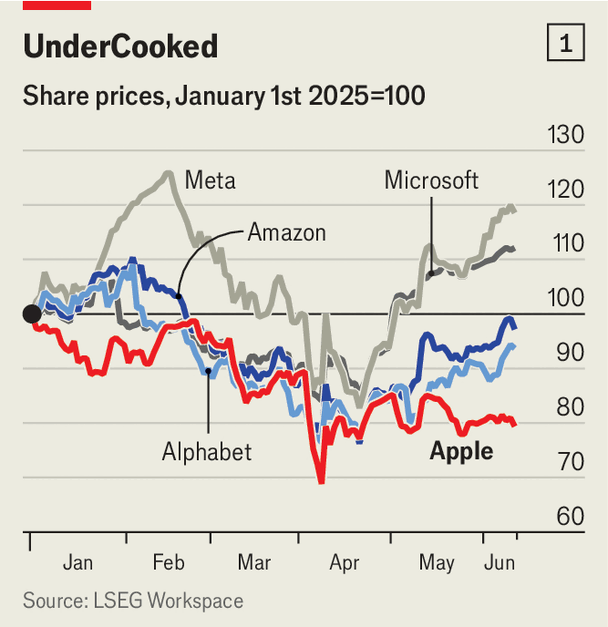

AYEAR AGO, when Apple used a jamboree at its home in Silicon Valley to unveil its artificial-intelligence (AI) strategy, grandly known as Apple Intelligence, it was a banner occasion. The following day the firm’s value soared by more than $200bn—one of the biggest single-day leaps of any company in history. The excitement was fuelled by hopes that generative AI would enable Apple to transform the iPhone into a digital assistant—in effect, Siri with a brain—helping to resuscitate flagging phone sales. Twelve months later, that excitement has turned into almost existential dread.

It is not just that many of last year’s promises have turned out to be vapourware. Siri’s overhaul has been indefinitely postponed, and Apple Intelligence is no match for other voice-activated AI assistants, such as Google’s Gemini. Meanwhile Apple’s vulnerabilities in China have been exposed by President Donald Trump’s trade war. Moreover, the company faces new legal and regulatory challenges to the two biggest parts of its high-margin services business.

Chart: The Economist

Apple’s shares, down by almost a fifth this year, have lagged behind its big-tech peers, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft (see chart 1). But those are not the most alarming comparisons. In a new book, “Apple in China”, Patrick McGee draws an ominous parallel between Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, and Jack Welch, boss of General Electric from 1981 to 2001. Like Welch, Mr Cook has made a fortune for investors. When Apple’s market value first exceeded $3trn, in 2022, it had risen by an average of more than $700m per day since he took over from Steve Jobs in 2011. But Mr McGee raises the possibility that, as at GE, Apple’s success may obscure serious vulnerabilities. If that is the case, what can Mr Cook do to avoid the sort of fate that befell GE and other once-great companies that suddenly lost their way, such as Nokia, a Finnish phone-maker that was disrupted by Apple in the late 2000s?

The answer did not emerge during the keynote address on June 9th at Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference. Unlike last year, Apple made few promises about AI, besides opening up the Apple Intelligence models on its devices to app developers. The biggest announcement was a refreshed look for its operating systems, which it called Liquid Glass.

Many would prefer to see Mr Cook work on a new hardware strategy instead. Craig Moffett of MoffettNathanson, an equity-research firm, notes that the greatest moments in Apple’s history have come from the reinvention of what techies call “form factors”: the Mac reimagined desktop computing, the iPod transformed music-listening habits and the iPhone popularised touchscreen smartphones. AI looks like it will be another such pivot point. (Eddy Cue, Apple’s head of services, recently admitted that AI could make the iPhone irrelevant in ten years.)

For now, Apple’s rivals have been faster to explore new opportunities. Meta and Google are pinning hopes on AI-infused smart glasses, as are Chinese tech firms such as Xiaomi and Baidu. OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT, recently announced a $6.4bn deal to buy a firm created by Jony Ive, Apple’s former chief designer, to build an AI device. As yet there is only hype to go on, but it has put Apple’s lack of AI innovation in the spotlight.

Apple’s response may seem like dogged incrementalism. Next year it is expected to unveil a foldable phone, following a path blazed previously by the likes of Samsung and Motorola. But Richard Windsor of Radio Free Mobile, a tech-research firm, thinks Apple may still have an ace up its sleeve. If smart glasses take off, its investment in the Vision Pro virtual-reality headset, though so far an expensive flop, may be a useful insurance policy. It could provide Apple with enough expertise in headgear and eyewear to shift quickly to glasses. If so, the company will avoid “doing a Nokia”, he says.

Questioning the Cookbook

Likewise, Apple might make use of this moment of soul-searching to rethink other shibboleths of Mr Cook’s tenure, such as the obsession with privacy and the high walls it puts around its family of products. As Ben Thompson of Stratechery, a newsletter, points out, sanctifying the privacy of its users’ data has been an easy virtue for Apple to uphold because until recently it did not have much of an advertising business. Yet in the AI era, prioritising privacy has drawbacks.

First, Apple’s reluctance to scrape customers’ individual information makes it harder to train personalised AI models. Apple uses what it calls “differential privacy” based on aggregate insights, rather than the rich, granular data hoovered up by firms such as Google. Second, privacy has encouraged it to prioritise AI that runs on its own devices, rather than investing in cloud infrastructure. Chatbots have advanced more rapidly in the cloud because the models can be bigger (awkwardly, this led Apple to offer some users of Apple Intelligence an opt-in to ChatGPT).

In order to overcome its AI deficiencies, it could splash out on buying a builder of cloud-based large language models (LLMs). But it has left that quite late. OpenAI’s deal with Mr Ive makes it less likely to ally with Apple. Anthropic is close to Amazon, which has a big stake in the maker of the Claude family of LLMs. Other options are either Chinese or too small for a company of Apple’s heft.

Alternatively, it could relax its “walled garden” ethos of seamless integration, and partner with a variety of third-party LLMs, as Motorola, owned by the Chinese firm Lenovo, has done. Third-party voice-activated chatbots could quickly solve its Siri problem, giving renewed reason for people to upgrade their phones.

The likelihood is that Mr Cook will do nothing radical. As Mr Moffett puts it, his tenure has been marked by the steady ascendancy of “process over product”. Instead of flashy innovations, his hallmark has been metronomic reliability, especially with regards to financial performance. Nor has he any hope of swiftly extricating Apple from China. As Mr McGee points out, even if Apple’s final assembly moves to India and other countries, the supply chain’s roots remain deeply embedded in the Middle Kingdom.

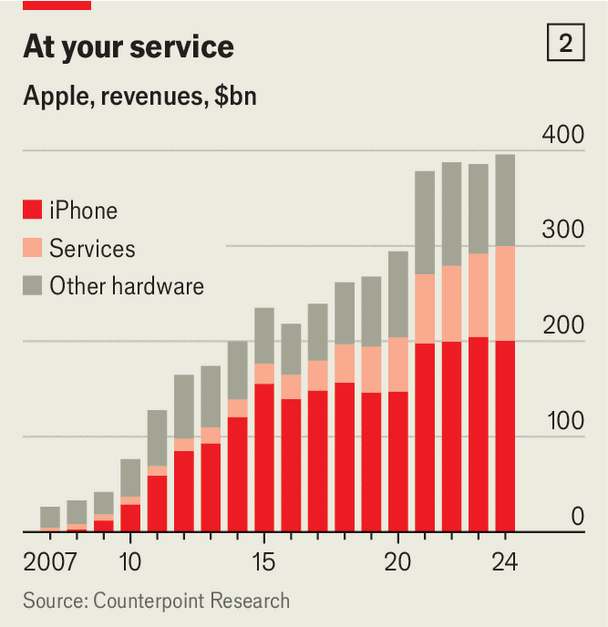

Chart: The Economist

Yet this is no time for complacency. Whatever the ups and downs of AI—as Google has recently shown, yesterday’s losers can quickly become today’s winners—nothing turns investors off quicker than a profits shock. That is what makes the threats to Apple’s services business so serious (see chart 2).

The most striking risk is that the judge who declared Google a monopolist may order it to suspend payments to Apple that make Google’s search engine the default on the iPhone. The payments, which are partly for exclusivity and partly a revenue-sharing arrangement, generate about $20bn a year for Apple (last year its services revenue was $96bn). David Vogt of UBS Investment Bank says that, if the judge imposes a ban on the exclusivity part of the payments, it could cut Apple’s revenue by about $10bn. “I’m getting calls every day of, ‘What will the market do to Apple stock if that happens?’” he says. Google has vowed to appeal.

Another looming threat is to app-store revenues, which are under scrutiny as a result of the EU’s Digital Markets Act, as well as from an antitrust lawsuit brought by Epic, a gaming firm, against Apple in America. Bank of America estimates that app-store commissions generate $31bn a year of high-margin services revenue for Apple. If app developers steer customers away from Apple’s app store as a result of the rulings, it could clobber the lucrative cash cow.

Services have been the brightest spot of Mr Cook’s tenure in recent years, helping to mitigate stagnation in iPhone sales. It will be a blow if the line of business suffers. But if it prompts Mr Cook to tear up his own rule book on AI and everything else, it may be worth it in the end. ■

China | Cash for clunkers

Chinese consumers are splurging—but probably not for long

There is a reason retail sales have boomed

Photograph: Getty Images

Jun 19th 2025|Hong Kong

Listen to this story

IN THE West the shopping calendar is organised around the birthday of Jesus Christ. In China it is shaped by the birthday of JD.com. That giant e-commerce firm, established on June 18th 1998, introduced the “618” shopping festival in honour of its founding. The festival offers discounts and other enticements to shoppers in the run-up to the big day. But just as Christmas decorations seem to appear earlier each year, the 618 festival keeps starting sooner. This year’s promotion began on May 13th, a week earlier than in 2024.

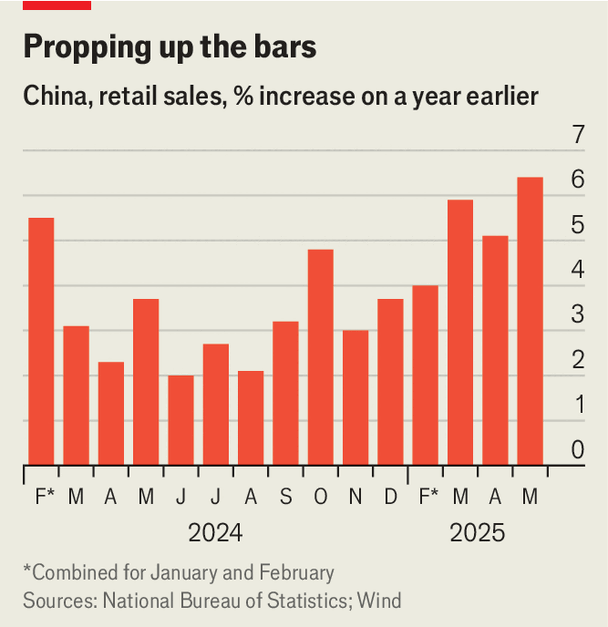

The early start helped boost last month’s retail sales, which grew by 6.4% year on year, faster than expected (see chart). The festival had stimulated “enthusiasm” among consumers, said China’s government, which has promised to boost consumption “vigorously” this year. It hopes higher household spending will defeat deflation and cut the economy’s reliance on investment spending (which is often wasteful) and foreign demand (which is threatened by tariffs).

Chart: The Economist

The month’s sales were also lifted by the government’s own attempt to reshape the country’s shopping schedules. Since early 2024 it has provided a steadily expanding subsidy to consumers who trade in old goods for newer, greener and snazzier versions. A variant on the “cash-for-clunkers” schemes popular after the global financial crisis of 2007-09, the programme now extends far beyond cars. According to government figures, it has subsidised the purchase of more than 77m household appliances, from refrigerators to air purifiers, in the first five months of this year. It has also financed discounts on more than 57m pieces of home decor, bathware or kitchenware, 6.5m electric bikes, and over 56m electronic goods, such as mobile phones.

In recent weeks the scheme has dovetailed with 618, allowing vendors to offer festival discounts, courtesy of the taxpayer. Some provincial governments now worry that they will run out of money for the programme long before its scheduled conclusion at the end of this year. The region of Xinjiang in the far west of China suspended its scheme on June 15th, saying that funds were almost exhausted. Chongqing, home to 32m people, has also run out of the money earmarked for home appliances. Several other provinces have imposed daily quotas on their subsidies. They are waiting for the central government, which provides roughly 90% of the money, to disburse the remaining funds: 138bn yuan ($19bn) out of the scheme’s 300bn-yuan budget. It will do so in an “orderly manner”, according to the Securities Times, an official newspaper.

Some provinces are taking advantage of the pause to tighten up their rules. An earlier version of the scheme last year was vulnerable to abuse. Some firms have captured the subsidy for themselves by raising their prices before applying the government discount. Others have claimed to sell the same item dozens of times. Firms must now match any subsidy to the unique serial number of a product. In some provinces couriers must provide a photo of an unwrapped, activated product at the consumer’s home to prove it has been sold.

Beyond these speed-bumps lies the bigger question of what happens when the government’s trade-in festival comes to an end. Many companies fear the schemes have merely front-loaded spending rather than substantially increased it. Strong retail sales now may be followed by unusually weak sales next year. If the property market has not stabilised by then, or if the trade war is still raging, the economy could be in real trouble. Even the big appliance-makers have doubts. Although they are taking advantage of the scheme, “deep down in their mind, they think this may create a lot of problems at a later stage,” says Chen Luo of Bank of America.

Festivals such as 618 have created similar problems in the past. During the pandemic, consumers took advantage of the deep discounts that were available on cosmetics to stock up with long-lasting beauty products, says Mr Luo. But that depressed sales for a while after, as people worked through their strategic lipstick reserves. To keep the recent momentum going, China’s government may find that it needs to offer more cash next year for a diminishing supply of clunkers. Just as the 618 festival keeps starting sooner, and Christmas lights keep twinkling earlier, China’s flagship stimulus scheme may keep getting longer. ■

United States | Lexington

The New York mayor’s race is a study in Democratic Party dysfunction

A party with a bad reputation for local governance shows few signs of turning that round

Illustration: João Fazenda

Jun 19th 2025

Listen to this story

New York City, America’s most innovative metropolis when it comes to making life harder than it needs to be, is about to perform that service for the national Democratic Party. As Democrats go to the polls to choose their next candidate for mayor, the big question is whether they will make their party’s path back to power in Washington rockier by only a little bit, or by a lot.

Polls show an overcrowded race narrowing to two candidates who are ideal only as foils for one another. Neither would dispel the cloud darkening the Democrats’ image when it comes to local governance. At the far left, perpetually smiling, is Zohran Mamdani, a 33-year-old Democratic Socialist with scant experience in leadership but grand plans. Towards the centre, glowering, is Andrew Cuomo, one of the more effective but also most scarred of Democratic politicians. He resigned in his third term as governor, in 2021, over accusations of sexual harassment that he denies.

Mr Cuomo, at 67 more than twice his rival’s age, is running as the reliable choice for New Yorkers who want their streets safer and their trash picked up. Yet not just his history of scandal but his long experience itself repels the college-educated, young white voters who are increasingly important in Democratic primaries in New York, as across the country. For them, he reeks of the past.

To these voters, Mr Mamdani—with his proposals for free bus services and city-run grocery stores, his censure of Israel and his artful TikTok videos—could have been dreamed up to embody the future by a benign Silicon-Valley genius, if they thought one existed. Mr Mamdani, a member of the state Assembly, would be the first immigrant mayor of New York in generations, and the first Muslim ever. He has mobilised thousands of volunteers, while Mr Cuomo has relied on a lavishly funded super-PAC. At a rally for Mr Mamdani on June 14th, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said a vote for him would “turn the page” to a party that “does not continue to repeat the mistakes that have landed us here”.

For Democrats rallying to Mr Cuomo, Ms Ocasio-Cortez and Mr Mamdani are making the mistakes, dragging the party down by alienating working-class voters with Utopian schemes that neglect fear of crime and frustration with high taxes and poor services. Mr Mamdani has run a disciplined campaign focused on affordability, and he has revised some past positions, such as defunding the police. Yet polls show Mr Cuomo receiving far more support from black and Latino New Yorkers, as Jacobin, a socialist magazine, noted. “We need to become more organically connected with the working-class constituency we hope to help organise,” the writer observed, in a timeless lament of the high-toned left.

Early voting is under way ahead of election day, June 24th. In all, 11 candidates are competing, under a ranked-choice voting system that makes the outcome hard to predict. Most candidates share Mr Mamdani’s contempt for Mr Cuomo, and they have been urging supporters not to include him among their five possible choices. Another of the many progressives, Brad Lander, the city’s comptroller, may have cut into Mr Mamdani’s support by getting arrested in front of reporters on June 17th while challenging federal agents to produce a warrant to detain an immigrant.

In the presidential election last autumn Kamala Harris sank under the burden of left-wing positions she took in the past, while moderate Democrats down-ballot outperformed more extreme candidates. Subsequently, conventional political wisdom appeared to be taking hold that the party needed to reclaim the political centre; Democrats with national ambitions have been deleting their “preferred pronouns” from their social-media bios. On June 10th, in one bellwether race, Democrats in New Jersey chose a moderate congresswoman, Mikie Sherrill, as their nominee for governor. But as the race in New York shows, Democrats’ identity and direction are far from settled questions, and much of the party’s dynamism and imagination remain with the left.

Donald Trump’s electoral success is driving the intraparty debate even as his actions in office create superficial unity. The candidates uniformly say they will resist Mr Trump, unlike the current Democratic mayor, Eric Adams, who extended some co-operation as Mr Trump’s Justice Department moved to dismiss corruption charges against him. Mr Adams, whose support has collapsed, plans to compete as an independent in the general election. The Democratic nomination is usually enough to secure the mayoralty, but, should Mr Cuomo or Mr Mamdani lose the primary, either could also run on another party’s lines, prolonging this struggle.

Three kings of Queens

Mr Adams’s pliability may explain why Mr Trump has yet to be as aggressive in New York as in Los Angeles. That is likely to change under the next mayor. Mr Cuomo, who like Mr Trump grew up in what was then the white ethnic Queens of Archie Bunker, touts his toughness, with reason; he is a bulldozer whose biggest obstacle has usually been himself. Mr Trump would not easily bait him into the political fights he loves (such as arresting Democrats who can be portrayed as grandstanding and obstructing justice).

For his part, Mr Mamdani declared in one debate, “I am Donald Trump’s worst nightmare, as a progressive Muslim immigrant who actually fights for the things that I believe in.” That is probably wrong. Mr Mamdani lives in Queens, but in the multi-ethnic, hipster oasis it is today. He grew up on the Upper West Side, the son of a professor of anthropology and an Oscar-nominated filmmaker. That may help explain why, like Mr Trump, he is such an adept social-media performer. But as a legislator he has delivered just three minor pieces of legislation, and nothing on his résumé suggests he is ready to competently deploy the city’s 360,000 workers or its $112bn budget. As New York’s mayor he is a leftist’s dream—and that makes him Mr Trump’s dream, too. ■

The Americas | More dirt

Police allege that Jair Bolsonaro sanctioned a spy ring

The right-wing former president is already on trial for allegedly plotting a coup

Charging aroundPhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 19th 2025|São Paulo

Listen to this story

Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right former president, is on trial for allegedly plotting a coup to stay in power after he lost an election in 2022. But the allegations do not end there. Police now say he approved the operation of an illegal spy ring to target his enemies.

On June 17th the federal police handed their inquiry to the attorney general. He will decide whether there is enough evidence for the accused to be tried. The police list numerous current and former officials who allegedly ran the surveillance network. They did not recommend indicting Mr Bolsonaro because he is already answering for related crimes as part of the coup trial. His son, Carlos, a councillor in Rio de Janeiro, and Alexandre Ramagem, Mr Bolsonaro’s former bodyguard, whom he appointed to lead the intelligence services in 2019, stand accused of masterminding the operations. Carlos says the investigations are politically motivated and Mr Ramagem says the police have created a “narrative”.

Police say the surveillance began after Mr Bolsonaro took office in 2019. Mr Ramagem allegedly ordered the use of geolocation software to track those critical of Mr Bolsonaro, as well as police officers who were investigating corruption. Police say the goal was to use the information on people’s whereabouts to smear Mr Bolsonaro’s opponents.

Mr Bolsonaro is already barred from next year’s presidential election. If found guilty for his role in a coup plot, he is expected to be sentenced to jail. But he is still Brazil’s most popular right-wing politician. He has no obvious successor. Another of his sons, Eduardo, a congressman, talks of running. A third son suggests that Mr Bolsonaro’s successor must pledge to pardon him. ■

Middle East & Africa | Cheap and deadly

Africa’s scary new age of high-tech warfare

The proliferation of new technology could make conflicts even longer and deadlier

Death from abovePhotograph: Getty Images

Jun 19th 2025|Addis Ababa

Listen to this story

Once infamous for fighting on horseback and ransacking villages like medieval raiders, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) recently acquired the weapons of 21st-century war. In early May the Sudanese militia, which has been fighting the country’s army since April 2023, launched drone strikes on Port Sudan, an army stronghold on the Red Sea coast. The attack damaged Sudan’s only functioning airport and the city’s main power station. Yet its most enduring impact was psychological. More than 1,000 kilometres away from any known RSF base, Port Sudan was long considered safe. The RSF’s drones demolished that assumption.

The strikes are the most recent illustration of how drones are changing the character of war in Africa. For decades the continent’s wars have been land-based, fought largely by light mobile infantry units. Air power was too costly and too complex for most armies. Today’s drones, by contrast, are both cheap and deadly. For now, they can sometimes provide a decisive advantage in a conflict. But they may ultimately make the continent’s wars easier to start and harder to end.

Chart: The Economist

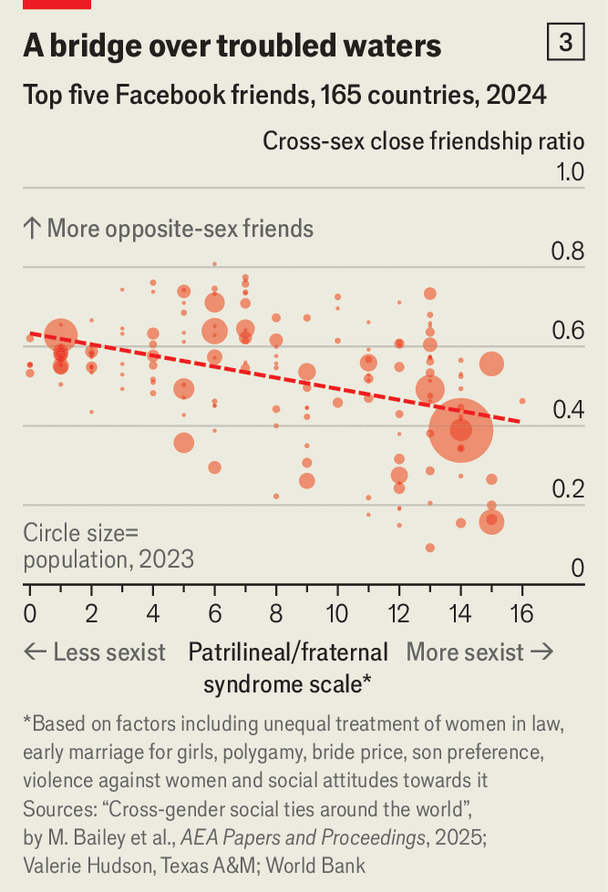

Drones are becoming ubiquitous in Africa. By 2023, some 30 African governments had bought an unmanned system of some kind. Data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED) show a surge in drone activity: 484 drone strikes were carried out across 13 African countries in 2024, more than twice as many as in 2023. More than 1,200 people were killed in such strikes (see chart).

Unlike the smaller first-person view (FPV) drones that litter the skies in Ukraine, most systems deployed by African forces are medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) drones. They are bulkier, fly at higher altitudes for longer, and carry larger payloads. The most popular is Turkey’s Bayraktar TB2, which costs around $5m. Other suppliers include the United Arab Emirates (UAE), China and Iran.

In Russia’s war in Ukraine, the ubiquity of drones on both sides has produced a grinding war of attrition. In Africa, drones have sometimes given one side a decisive advantage. In the summer of 2021 rebel forces from Tigray in northern Ethiopia marched to the gates of the capital, Addis Ababa, threatening to topple the government. But the stunning offensive left the rebels’ supply lines exposed. The Ethiopian government had built up a large arsenal of drones from Turkey, Iran and the UAE. It used them to wreak havoc on Tigrayan logistics and beat back the assault, a turning-point in a war it eventually won. “We could have captured Addis easily,” laments a former intelligence officer from Tigray, who was involved in the offensive. “It was those fucking drones…We had no way of shooting them down.”

Drones have shifted the balance of power in other conflicts, too. Before the RSF’s attacks on Port Sudan, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) used drones to attack the RSF’s supply lines, helping it recapture Khartoum, the capital, in March. In 2023 Turkish drones helped Mali’s junta retake the northern city of Kidal, booting out the Tuareg separatists who had ruled it for more than a decade.

Yet drones alone cannot always turn the tide. The SAF’s recapture of Khartoum required months of gruelling, door-to-door fighting, even though drones helped with intelligence-gathering. They are not particularly useful when opponents hide in mountains or rainforests, or embed with civilian populations. Despite their success in Tigray, Ethiopia’s drones have been ineffective against rebels in the mountainous Amhara region. In Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, drones struggle to cover the vast distances involved in campaigns in the Sahel. Jihadist insurgencies there continue to spread as fighters have been quick to adapt to the new threat. They now use motorbikes instead of pickup trucks, so they can disperse fast and evade aerial surveillance. In eastern Congo fighters from M23, a militia backed by Rwanda, have used jammers to blunt drones fielded by UN peacekeepers. They reportedly shot down a Chinese MALE drone used by Congo’s army.

Most importantly, because drones are cheap, plentiful and easy to transport, they can be acquired by all sides in a conflict. On June 13th Tuareg insurgents in northern Mali appear to have used FPV drones, similar to those used by Ukraine, to devastate a convoy of Russian mercenaries crossing the desert.

The proliferation of drones offers governments a cheap way to keep rebels in check without suffering many casualties. That could lower their willingness to strike negotiated agreements. It also boosts the arsenals of non-state actors and makes it easier for foreign powers to support proxies in Africa. The result could be more and longer wars on the continent. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Europe wants to show it is ready for war. But would anyone show up to fight one?

The “peace project” at the heart of the continent has worked rather too well

Illustration: Ellie Foreman-Peck

Jun 19th 2025

Listen to this story

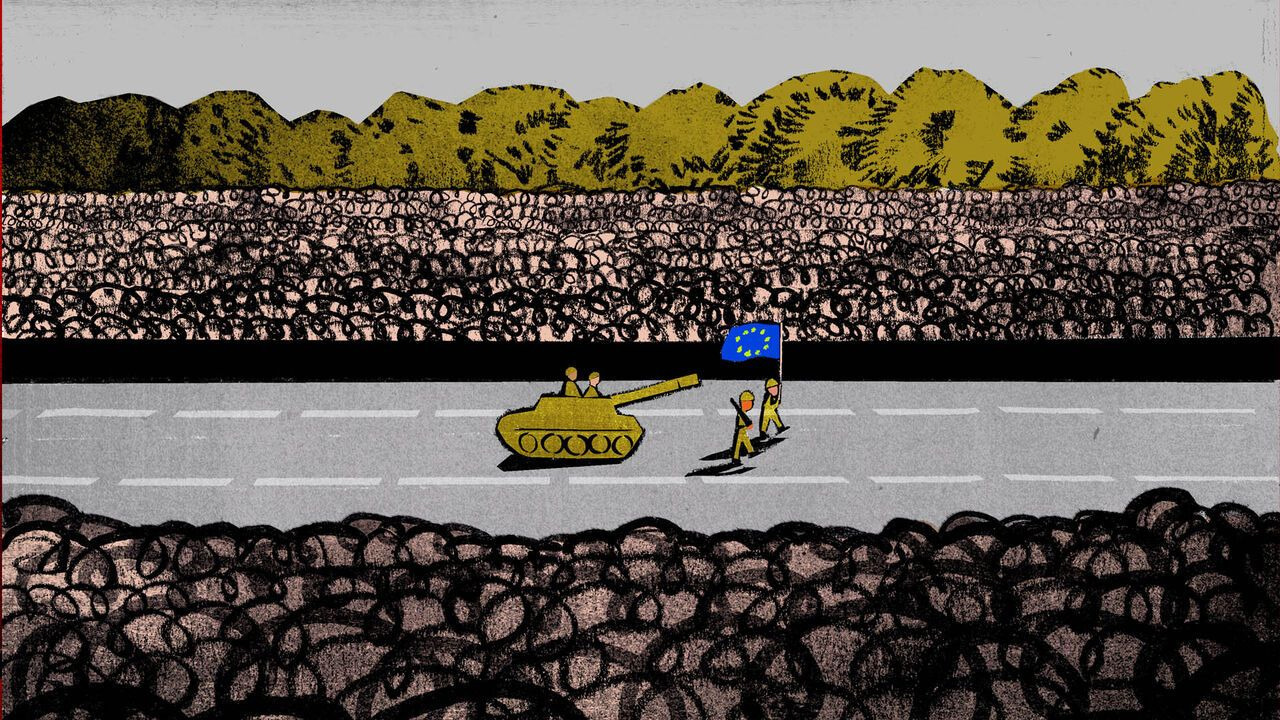

Nice tanks you got there, Europe—got anyone to drive ’em? Such are the taunts the continent’s generals might have to endure following the announcement of a splurge in defence spending expected from the NATO summit in The Hague on June 24th-25th. Assuming European governments don’t bin their commitments to bigger defence budgets once some kind of peace is agreed to in Ukraine—or Donald Trump leaves the White House—spending on their armed forces will roughly double within a decade. A disproportionate slug of the jump from a 2% of GDP spending target to 3.5% will go towards purchasing equipment. But armies are about people, too. Attracting youngsters to a career that involves getting shot at has never been easy; a bit of forceful nagging (known in military jargon as “conscription”) is already on the cards in some countries. Even dragooning recalcitrant teens into uniform will not solve a problem that is lurking deep in the continent’s psyche. Europeans are proud of their peaceful ways. If war breaks out there, will anybody be there to fight it?

Polling that asks people how they would behave in case of an invasion ought to send shivers down the spines of Europe’s drill sergeants. Last year a Gallup survey asked citizens in 45 countries how willing they would be to take up arms in case of war. Four of the five places with the least enthusiastic fighters globally were in Europe, including Spain, Germany and notably Italy, where just 14% of respondents said they were up for taking on a foreign foe. Given Russia’s snail-paced advances since it launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, countries over a thousand kilometres away from today’s front lines may not feel the chill wind of the Kremlin. But even in Poland, which shares a border with Ukraine (and with the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad), fewer than half of respondents say they would fight in a war involving their country. In a separate poll taken before the invasion, 23% of Lithuanian men said they would rather flee abroad than fend off an attack. Citizens asked to stand up and be counted are giving a resounding shrug instead.

To some Europeans, a citizenry with no appetite for fighting is the reflection of a job well done. The union at the continent’s heart bills itself as a “peace project”. The past seven decades have been about ensuring Germany would never take up arms against France and vice versa. Meshing economies together within the European Union and even outside it was meant to make invasions impractical at first and unthinkable in time. The bureaucratic pacificism that endures within the EU—“make meetings not war!” would be a fine motto—may have resonated a bit too much with some citizens. Some may have forgotten that those outside the club, like one Vladimir Putin, were not privy to such arrangements. Military matters were at most an afterthought. Only in the past year has the bloc appointed a commissioner for defence, while making clear the job is about overseeing the companies making shells and missiles, not the armed forces per se.

To what can the broader population’s lack of appetite to bear arms even in case of war be attributed? Sociologists speak of Europe as a “post-heroic” society, where individualism and aspirations of “self-realisation” trump the supposed patriotic fervour of generations past. The continent’s polarised politics have played a part: support for parties of the hard right and left has surged in recent decades, and their voters are notably cooler on the idea of fighting for their country. Older people tend to be less gung-ho about taking up arms, and Europe is an ageing continent. Places with recent histories of dictatorship, such as Spain and Portugal, are also gun-shy. Seeing misfiring American operations in Afghanistan and Iraq (in which Europeans had at best a supporting role) comforted pacifists that theirs was the right way.

Notwithstanding its peace-mongering ways, Europe does not lack men and women in uniform. Despite a scything in the number of troops since 1990, to less than half the previous figure in many countries, the continent still has more soldiers than America, and roughly as many as a share of its overall population. Still, some countries like Poland are now talking of bringing some form of conscription back (a few, like Denmark and Greece, never quite got rid of it). Abolishing military service was once hailed as a liberal accomplishment. Now drafting youngsters is seen as a way of promoting the idea that national defence is everybody’s job, not just the role of a few paid soldiers.

The fog of peace

That notion may take a while to take hold. For something strange happens when you ask Europeans about defence matters. In surveys carried out by the European Commission, the bloc’s citizens list Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and matters of defence as the biggest threats facing the EU as a whole. Well over half think that fighting within the union’s borders is likely in coming years. But asked what issues affect them personally and Europeans forget about Russia altogether, worrying more about inflation, taxes, pensions and climate change than they do about potential invaders. It is not that Europeans don’t see the looming threat. It is that they think it is somebody else’s problem.

The upshot is a continent that gives the impression of being battle-weary without having fought the battle. Already Trumpians have a dim view of Europeans’ fighting verve. J.D. Vance, the American vice-president, in March dismissed the possibility of “some random [European] country that hasn’t fought a war in 30 or 40 years” credibly deterring Russia by putting boots on the ground in Ukraine. It was offensive precisely because it contained elements of truth. Getting Europeans to shell out for more of their own defence has taken decades of Americans nagging. Convincing them to give war a chance might take even longer. ■

Britain | Child sexual exploitation

The grooming-gangs scandal is a stain on the British state

It involved a toxic combination of victim-blaming and misguided political correctness

A case study in institutional failurePhotograph: Reuters

Jun 18th 2025

Listen to this story

MOHAMMED ZAHID ran a clothes stall in Rochdale market, and a grooming gang. He employed vulnerable girls, offering them gifts of alcohol and underwear, and targeted others when they came to buy tights for school. Along with his friends, who included other Pakistan-born stallholders and taxi drivers, Mr Zahid then treated the children as sex slaves, raping and abusing them in shops, warehouses and on nearby moors. Among his victims were two 13-year-old girls. One was in care; both were known to social services and the police. On June 13th, almost 25 years after the abuse began, Mr Zahid and six others were convicted of 30 counts of rape.

Britain’s grooming-gangs scandal, the long-ignored group-based sexual abuse of children, has been a stain on the country for decades. Yet justice for victims and action to tackle failures have been painfully slow. On June 16th the government published an audit, which pinned the blame on authorities that failed to see “girls as girls” and “shied away from” looking into crimes committed by minorities—in this case often men of Asian or Muslim (especially Pakistani) heritage. Yvette Cooper, the home secretary, announced a raft of measures, including new criminal investigations. At last, the government is getting to grips with a scandal that should remain a case study in institutional failure.

The latest report follows a succession of probes stretching back over a decade. Those include two long public inquiries, one completed in 2015 into gangs in Rotherham, another in 2022 into child-sexual exploitation more broadly. Despite taking four months, this audit provided new and valuable insights for two reasons. It was the first to look solely at grooming gangs nationally. And it was led by Louise Casey, a cross-bench peer and social-policy fixer with a reputation for plain speaking.

Lady Casey begins by observing that, even now, it is impossible to know the scale of this problem. That is in part because these are horribly complex cases, victims fear coming forward and investigations were badly botched. Police forces failed to collect data. Grooming gangs have been identified in dozens of towns and cities. In Rotherham alone, thanks to an unusually thorough police investigation led by the National Crime Agency (NCA), 1,100 victims were identified. Our rough calculation suggests that tens of thousands of victims could be awaiting justice.

Lady Casey’s most significant contribution is on the role of ethnicity. It was known that some police forces failed to look into reports of Asian grooming gangs out of a fear of appearing racist or upsetting community relations. She goes beyond this, strongly criticising a Home Office report from 2020, which claimed in spite of very poor data that the ethnic composition of groups that sexually exploited children was likely in line with the general population, with “the majority of offenders being White”. No such conclusions can be drawn, she says. Instead she cites new, more solid data, unearthed from three police forces, showing that suspects were disproportionately of Asian heritage; in Greater Manchester, more than half were.

Will this time be different?

There is no evidence to support the idea, found on the right, that Asian men are more likely to commit sexual or child-sexual abuse in general. Yet the refusal of some on the left to grapple with the role of culture and ethnicity in group-based abuse was inexcusable. What marks these crimes out, says Sunder Katwala of British Future, a think-tank, is precisely that perpetrators become disinhibited from moral norms as a group. Asian men appeared to target white girls in part because they were from another community. Cultural over-sensitivity may also have blinded the police to obvious patterns, like the role of (disproportionately Asian) taxi drivers employed by councils to ferry vulnerable children.

Lady Casey also shines a light on sexism and classism running through the state. Presented with evidence of predatory gangs, the police’s reaction was often to treat victims as “wayward teenagers” or adults who had made bad choices. Many were not believed—some were criminalised as child prostitutes. Ms Cooper will change the law to prevent rapists getting away with lesser charges by claiming that 13- to 15-year-olds had “consented” to sex.

The home secretary also, sensibly, announced that the NCA would take over hundreds of cold cases. Attention, however, focused on her reversal in calling another public inquiry. Such inquiries have become something of a national addiction, often less fact-finding probes than expensive and cumbersome attempts at catharsis. In this case one seems warranted: earlier inquiries have left basic gaps, and statutory powers could be used to compel local police forces and councils to release documents, as happened in Rotherham.

Kemi Badenoch, the Tory leader who had called for such a U-turn, reacted gleefully, accusing the government of having attempted a cover-up. That trivialises the depth and breadth of the failure, which successive politicians in Westminster have overlooked (the home secretary at the time of the 2020 report was Priti Patel, a Conservative). But many recommendations from previous inquiries, covering issues from data sharing to victim support, have not been implemented, owing to a lack of political interest and bureaucratic inertia. This time, the hope must be that attention is sustained, and many more predators like Mr Zahid end up behind bars. ■

International | The Telegram

In Trumpworld, toppling rulers is taboo

Donald Trump prefers deals to regime change

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Jun 17th 2025

Listen to this story

BY THE TIME the Iran crisis ends, President Donald Trump risks breaking some solemn promises about war and peace. Large-scale American help to destroy Iran’s deeply buried nuclear sites would imperil his pledge to keep America out of Middle Eastern conflicts. Yet if his caution allows a wounded Iran to successfully sprint for a bomb, that would challenge Mr Trump’s stated belief that “you can’t have peace if Iran has a nuclear weapon”.