The Economist Articles for July 3rd week : July. 20th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.07.11조회수50 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for July 3rd week : July. 20th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | It is not working

Scrap the asylum system—and build something better

Rich countries need to separate asylum from labour migration

Jul 10th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

THE RUles for refugees arose haphazardly. The UN Refugee Convention of 1951 applied only to Europe, and aimed to stop fugitives from Stalin being sent back to face his fury. It declared that anyone forced to flee by a “well-founded fear” of persecution must have sanctuary, and must not be returned to face peril (the principle of “non-refoulement”). In 1967 the treaty was extended to the rest of the world.

Most countries have signed it. Yet dwindling numbers honour it. China admits fewer refugees than tiny Lesotho and sends North Koreans home to face the gulag. President Donald Trump has ended asylum in America for nearly everyone except white South Africans, and plans to spend more on deporting irregular migrants than other countries spend on defence. Western attitudes are hardening. In Europe the views of social democrats and right-wing populists are converging.

The system is not working. Designed for post-war Europe, it cannot cope with a world of proliferating conflict, cheap travel and huge wage disparities. Roughly 900m people would like to migrate permanently. Since it is almost impossible for a citizen of a poor country to move legally to a rich one, many move without permission. In the past two decades many have discovered that asylum offers a back door. Instead of crossing a border stealthily, as in the past, they walk up to a border guard and request asylum, knowing that the claim will take years to adjudicate and, in the meantime, they can melt into the shadows and find work.

Voters are right to think the system has been gamed. Most asylum claims in the European Union are now rejected outright. Fear of border chaos has fuelled the rise of populism, from Brexit to Donald Trump, and poisoned the debate about legal migration. To create a system that offers safety for those who need it but also a reasonable flow of labour migration, policymakers need to separate one from the other.

Around 123m people have been displaced by conflict, disaster or persecution, three times more than in 2010, partly because wars are lasting longer. All these people have a right to seek safety. But “safety” need not mean access to a rich country’s labour market. Indeed, resettlement in rich countries will never be more than a tiny part of the solution. In 2023 OECD countries received 2.7m claims for asylum—a record number, but a pinprick compared with the size of the problem.

The most pragmatic approach would be to offer more refugees sanctuary close to home. Typically, this means in the first safe country or regional bloc where they set foot. Refugees who travel shorter distances are more likely one day to return home. They are also more likely to be welcomed by their hosts, who tend to be culturally close to them and to be aware that they are seeking the first available refuge from a calamity. This is why Europeans have largely welcomed Ukrainians, Turks have been generous to Syrians and Chadians to Sudanese.

Looking after refugees closer to home is often much cheaper. The UN refugee agency spends less than $1 a day on each refugee in Chad. Given limited budgets, rich countries would help far more people by funding refugee agencies properly—which they currently do not—than by housing refugees in first-world hostels or paying armies of lawyers to argue over their cases. They should also assist the host countries generously, and encourage them to let refugees support themselves by working, as an increasing number do.

Compassionate Westerners may feel an urge to help the refugees they see arriving on their shores. But if the journey is long, arduous and costly, the ones who complete it will usually not be the most desperate, but male, healthy and relatively well-off. Fugitives from Syria’s war who made it to next-door Turkey were a broad cross-section of Syrians; those who reached Europe were 15 times more likely to have college degrees. When Germany opened its doors to Syrians in 2015-16, it inspired 1m refugees who had already found safety in Turkey to move to Europe in pursuit of higher wages. Many went on to lead productive lives, but it is not obvious why they deserved priority over the legions of other, sometimes better-qualified people who would have relished the same opportunity.

Voters have made clear they want to choose whom to let in—and this does not mean everyone who shows up and claims asylum. If rich countries want to stem such arrivals, they need to change the incentives. Migrants who trek from a safe country to a richer one should not be considered for asylum. Those who arrive should be sent to a third country for processing. If governments want to host refugees from far-off places, they can select them at source, where the UN already registers them as they flee from war zones.

Some courts will say this violates the principle of non-refoulement. But it need not if the third country is safe. Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister, wants to send asylum-seekers to have their cases heard in Albania, which qualifies. South Sudan, where Mr Trump wants to dump illicit migrants, does not. Deals can be done to win the co-operation of third-country governments, especially if rich countries act together, as the EU is starting to. Once it becomes clear that arriving uninvited confers no advantage, the numbers doing so will plummet.

The politics of the possible

That should restore order at the frontier, and so create political space for a calmer discussion of labour migration. Rich countries would benefit from more foreign brains. Many also want young hands to work on farms and in care homes, as Ms Meloni proposes. An orderly influx of talent would make both host countries and the migrants themselves more prosperous.

Dealing with the backlog of previous irregular arrivals would still be hard. Mr Trump’s policy of mass deportation is both cruel and expensive. Far better to let those who have put down roots stay, while securing the border and changing the incentives for future arrivals. If liberals do not build a better system, populists will build a worse one. ■

Leaders | Hormones

Sex hormones could be mental-health drugs too

If they can be liberated from ignorance and hucksterism

Illustration: Nathalie Lees

Jul 10th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

POOR MENTAL health is a scourge. Prescriptions for anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medicines have soared in rich countries in recent decades. Yet they do not work for everyone. Perhaps a third of people with serious depression, for instance, report that drugs seem to have little effect. Doctors are therefore beginning to look further afield.

As we report this week, one promising area is hormone therapy. The idea is to boost levels of naturally occurring hormones in patients’ bodies—and in particular, to tweak sex hormones such as oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone. New ways to treat mental illness should be celebrated. Making the most of them, however, will involve dispelling the poor reputation that hormones have gained over the years.

Hormone-replacement therapy (HRT) is best known as a treatment for the physical symptoms, such as hot flushes or night sweats, that come with menopause, when a woman’s levels of oestrogen and progesterone drop. But, as any parent of teenagers will tell you, hormones can influence the mind as well as the body. Evidence suggests that restoring hormone levels can sometimes ease symptoms of many disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, that have resisted other treatments.

It is not just women who can benefit. Men do not experience anything like the fluctuation in hormones tied to various life stages such as menopause. But many (perhaps a third of older men) seem to have lower levels of testosterone than they should. There is growing evidence that giving those men extra testosterone can help with mood disorders, too.

The problem is that many patients—and even some doctors—remain wary of hormonal treatments, because of their bad name among the public. Excessive worries about a small increase in breast-cancer risk have dogged women’s HRT since the early years of this century. Even now, only 5% or so of menopausal women in America take it. This situation is not helped by the persistence of the naturalistic fallacy, which holds that what is natural—like the menopause and male ageing—must be good, and so is not in need of treatment.

With testosterone replacement in men, the problem is too much enthusiasm among people who want cosmetic rather than medical benefits. Testosterone is a potent performance-enhancing drug. In America, in particular, an industry has emerged to sell the hormone to middle-aged men. Rife with hucksters and Instagram influencers, it pitches testosterone as a fountain of youth: a way to pack on muscle, restore sex drive and generally turn back the clock on ageing. Less is said about the downsides: that testosterone causes infertility, say, or that high doses are bad for your heart. Even the clinics themselves admit that shady prescribing is driving the industry into disrepute, though many say their rivals are to blame.

For the testosterone business, better regulation is the place to start. Clinics should be required to test their customers and clearly spell out the downsides. For women, awareness is the key. Fears about HRT and breast cancer have been overplayed; and anyway, HRT brings health benefits by, for example, cutting the risk of osteoporosis. When it comes to mental health, hormonal treatments should undergo clinical trials to identify which patients stand to benefit: because hormones are cheap, the gains could be huge. If patients can be made less wary of sex hormones, many more people could be helped by them—for ailments of the mind as well as of the body. ■

Asia | Banyan

Mahathir Mohamad, the leader who transformed Malaysia, turns 100

His vision for the country remains thankfully unrealised

Illustration: Lan Truong

Jul 10th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD, Malaysia’s prime minister from 1981 to 2003 and again from 2018 to 2020, resembles other statesmen he hobnobbed with back in the 1980s—such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Lee Kuan Yew and Deng Xiaoping. All of them had distinctive policies; all presided over an economic transformation; all were larger than life. Only Dr Mahathir, however, is still alive, turning 100 on July 10th. He continues to wield influence, not just through his past achievements but as an active dabbler in politics. Sadly, that influence is mostly baleful.

As prime minister for 24 of the past 44 years, Dr Mahathir is due considerable credit for Malaysia’s economic success. In 1981 it still relied heavily on commodity exports—first rubber and tin, industries the British empire had nurtured, and then petroleum, timber and palm oil. It is now a diversified manufacturing hub, with electronics its most important export.

Dr Mahathir was often abrasive towards the outside world, but he nevertheless welcomed foreign investment. He oversaw Malaysia’s rapid integration into global supply chains and the building of impressive infrastructure (as well as some expensive flops, such as a national carmaker). GDP per person rose from about $1,900 in 1980 to about $12,500 last year.

His reputation for economic management was enhanced by his unorthodox response to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. The Malaysian ringgit plunged and the economy slumped, but Dr Mahathir rejected IMF help. He imposed capital controls and pegged the currency to the dollar. When Malaysia quickly recovered, he could claim victory.

This record helps explain his enduring popularity. So too does his image as a straight-talking man of the people—a doctor from humble origins, willing to fight for the truth as he sees it. Hence his remarkable comeback in 2018, when he joined his former deputy, and later nemesis, Anwar Ibrahim, to topple another of his protégés, Najib Razak.

Yet politically Dr Mahathir has left a largely toxic legacy. The issues that have driven him have been the most sensitive in Malaysian society: race and religion. (The concepts are inseparable in Malaysia, as the constitution insists a Malay must be Muslim.) The inflammatory book he published in 1970, “The Malay Dilemma”, castigated Malays, who then made up 56% of the population, for accepting a second-class status. Farming and fishing were lazy options that hampered the growth of the Malay community, he argued. He supported the affirmative-action policies that favour Malays over the Chinese and Indian minorities (then 34% and 9% of the population respectively), whom Dr Mahathir throughout his career has berated for perceived disloyalty to Malaysia.

In 1980 the ethnic-Chinese minority dominated business. The attempt to redress this imbalance through affirmative action, with lavish public funding for favoured Malay businessmen, had predictable effects: a culture of corruption and cronyism that thrived long after Dr Mahathir stepped down, culminating in the 1MDB scandal, exposed in 2015, in which billions of dollars were stolen from a sovereign wealth fund by well-connected insiders. (Mr Najib is now in jail on related charges.)

Dr Mahathir can also be blamed for the weakening of some of the institutions and people that might have provided better oversight and accountability, including of himself. In the 1980s he engaged in a series of confrontations: with the judiciary; the traditional hereditary Malay rulers of nine of the country’s states; and his political opponents, against whom he deployed an Internal Security Act, bequeathed by the British, to arrest more than 100 politicians, academics, activists and others in 1987. The trend was towards a stronger executive branch, with weaker accountability.

Ironically, Dr Mahathir’s victory in 2018 at the head of a breakaway party meant a first-ever electoral defeat for the United Malays National Organisation, the party he did so much to build as a vehicle for Malay political dominance. Worse, for Dr Mahathir, his coalition was short-lived. He lost power in 2020 and saw Mr Anwar become prime minister two years later.

Dr Mahathir fights on for his divisive vision of Malaysian society. Surely it is too late for another comeback. But he remains an obstacle to the relaxed multicultural society Malaysia might become. Impeding that progress may be his most lasting legacy. ■

China | Left in the lurch

Why so many Chinese are drowning in debt

Some contemplate suicide. Others vaunt their folly as influencers

Illustration: Ben Hickey

Jul 7th 2025|HANGZHOU|6 min read

Listen to this story

THE RISE of a property-owning, entrepreneurial middle class in China has transformed its cities in this century. It has helped to spur consumption in the world’s second-largest economy. In May retail sales grew by 6.4% year on year—the fastest pace since December 2023—helped by state subsidies aimed at reviving consumers’ enthusiasm. The government has even cautiously promoted borrowing in past years. But all this has created new risks. Along with car-jammed streets, glitzy restaurants and vast malls has come an invisible change that is no less great: soaring household debt.

As a proportion of China’s GDP, household debt has risen from less than 11% in 2006 to more than 60% today, close to rich-country levels. Lenders include state-owned banks and tech platforms. Between 25m and 34m people may now be in default, according to Gavekal Dragonomics, a research consultancy. If those merely in arrears are added, the total could be between 61m and 83m, or 5-7% of the total population aged 15 and older. In both categories, these numbers are twice as high as they were five years ago, the firm reckons. Amid high youth unemployment and a property slump, things may only worsen.

Dealing with personal debt remains shameful and unfamiliar in China. But the government is struggling to help. It is already busy tackling debt throughout the system: local-government debt remains painfully high, and corporate debt uncomfortably so. Household debt is one more worry. It is not an imminent threat to financial stability. But it weighs increasingly heavily on the minds of middle-class people, inhibiting their spending and undermining a belief in ever-rising prosperity that the Communist Party sees as crucial to keeping its grip on power.

Chinese households have a buffer: overall, their savings relative to disposable income were nearly 32% in 2023, according to JPMorgan Chase, a bank. That is far higher than the rate of less than 3% in America in the build-up to the global financial crisis in 2007. But in the boom years money borrowed for housing seemed like a one-way bet, especially as jobs were plentiful and secure. People grew accustomed to splashing cash from big online lenders such as Alipay and WeBank. Others borrowed to invest in family firms. Then came zero-covid lockdowns in 2020 and the start of the property crash the year after. Whatever the origins, debt trouble and interactions with cuigou, or “pressure dogs” (aggressive debt-collectors), have been the fate of many.

Start with property. Borrowing for housing made up 65% of household loans last year (excluding loans for business purposes). Most mortgage lending is done by government-owned banks, which have to be careful about how they get their money back from those unable to pay. The number of foreclosed residential properties listed for auction last year was 366,000, slightly up from 364,000 in 2023, according to China Index Academy, a private research firm. The number of people failing to pay their mortgages may be growing much faster. Regulators are wary of aggressive repossessions involving people’s primary homes: they worry about triggering public protests. Banks may be mulling another problem. In today’s depressed market, auctioning a property may not recoup the mortgage. Online lenders, which provide a more modest share of mortgages, can be far tougher about repayment.

Spendthrifts are another group in trouble. Lily, a millennial in Shanghai, got into debt when her employer, a software firm, stopped paying her wages because of its own cashflow difficulties. She owed 30,000 yuan ($4,200) to online lenders. To help, she is dabbling in “debt IP”—when people turn stories of ruin into a means of generating cash as online influencers. She describes her travails in short videos on social media, but hasn’t hit the big-time. Some of the most popular accounts have hundreds of thousands of followers. “Some people are even competing: ‘Oh, I’m 10m in debt, I’m 100m in debt,’” she says.

Now consider investment debt. In Hangzhou, Ms Bai used to run a big education business and took out personal loans of millions of yuan to invest in it. Many Chinese borrow to boost family-owned firms and lenders often require personal guarantees, putting households at risk if the ventures fail. At its peak, her business organised cramming classes for between 50,000 and 60,000 students at 30-odd tutoring centres, generating an annual revenue of 100m-200m yuan. Then came covid-19 and a political crackdown on crammers. She had to sell her house and car to pay the debt.

Dealing with the banks was the easy bit, however. During the pandemic the government urged them to be gentle with debtors whose businesses had been affected by it; they agreed to waive tens of thousands of yuan in interest. The tough part was dealing with the pressure dogs hired by online lenders from whom she had borrowed money for personal use. They repeatedly called Ms Bai, her friends and her relatives, often from different phones so they could not be blocked. She is particularly angry about the harassment of her parents. “In China”, she says, “we generally don’t tell our parents about bad news, so they were very, very affected.” Ms Bai became depressed and thought of suicide. Her husband divorced her.

Regulations relating to the debt-collecting industry are new and patchily enforced in China. Rather than helping Ms Bai, a court put her on a “social credit” blacklist, which meant she could no longer fly, use high-speed trains or stay at luxury hotels. So where can debtors find relief? Support groups for them have been growing online. Jiaqi Guo of the University of Turku in Finland has been studying one of them, called the Debtors Alliance, on Douban, a social-networking site. Founded in 2019, it now has more than 60,000 members. Dr Guo says users often discuss shesi, meaning “social death”. It refers to the destruction of relationships caused by “contact bombing”, as the debt collectors’ phone calls are described.

The government has tried to show a modicum of sympathy. Last year it banned debt-collection agencies from threatening violence, using abusive language or calling people at anti-social times. It also reminded lenders to protect personal information (presumably meaning stopping misusing contact details). But data-privacy regulations are loosely enforced in China. Complaints on the debtors’ forum suggest little change in the collectors’ threatening and intrusive behaviour.

One reform that might help is a personal-bankruptcy law, of the kind found in rich countries, to protect debtors from claims that would leave them destitute. The lack of such legislation has fuelled the growth of online loan-sharks offering high-interest credit to desperate defaulters. In 2021 Shenzhen became the first city to introduce a bankruptcy law for individuals. But it has been used with caution. By the end of September 2024 more than 2,700 people had applied for bankruptcy protection under this law, but courts had accepted only about 10% of their cases. A few other places have been dabbling in similar schemes. But the government appears in no hurry: creditors are often big state firms. Officials worry that a national law might signal tolerance of reckless spending or speculative investment. ■

United States | Hormonal men

American men are hungry for injectable testosterone

A legion of new health clinics are serving it up

Joe says it is soPhotograph: Scott McIntyre/The New York Times/Redux/Eyevine

Jul 8th 2025|ATLANTA|5 min read

Listen to this story

ARE YOU struggling to be the man you were always meant to be? You might have low testosterone. Walk into Gameday Men’s Health clinic and you will find yourself in their “man cave”, a waiting-room decked out with black leather armchairs, televisions and a well-stocked fridge. A nurse practitioner will do a blood test and check if your testosterone levels are normal. If you are indeed deficient—or if you’re technically not but you’re experiencing symptoms of exhaustion, depression or trouble putting on muscle and having stamina during sex—they can inject you with your first dose of testosterone within the hour.

Refer a friend for $50 off your next weekly treatment.

The Gameday clinic in the ritzy Buckhead neighbourhood of Atlanta, Georgia, opened in April last year as the company’s 50th franchise. In the 14 months since, another 325 have been launched across the country. This represents a burgeoning American health trend. Between 2019 and 2024 prescriptions for testosterone jumped from 7.3m to 11m. In Texas, the hub for testosterone-replacement therapy (TRT), a medical treatment that artificially increases hormone levels and Gameday’s most popular service, there were more scripts filled in the final quarter of last year than in all of 2021. Because hormone levels naturally fall as people age, middle-aged men inject it at higher rates than anyone else. But the demographic group that is taking to it fastest is men under the age of 35.

Like many wellness fads, the testosterone craze aims to fix a real medical problem. There is some evidence that men today, on average, have lower testosterone levels than men did decades ago, thanks to higher rates of diabetes, obesity, opioid use and more exposure to environmental toxins. That makes them feel lousier than they ought to. According to Mohit Khera of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, 92% of men with low testosterone suffer from depression and a simple blood test can change their lives for the better. Hypogonadism, the condition, too often goes undiagnosed. Injections can dramatically improve mood, sleep and libido and reduce body fat. Clever entrepreneurs, like Casey Burt of Gameday Buckhead, reckon that the market is still partially untapped: doing away with the stigma around sexual health will reveal more patients who genuinely need care.

Its loudest proponents, however, are not doctors. Joe Rogan, America’s top podcaster, touts it to his 20m listeners as a way to help men feel younger. Dax Shepard, an actor and podcaster, says that “heavy testosterone injections” helped him gain 24 pounds of muscle. “I spent my whole life as a medium boy and now I’m a big boy and I like it,” he says. (Because it is a steroid that very effectively improves athletic performance, testosterone is banned in most professional sports.) Buff gym-bros and “biohackers” inject themselves on TikTok while telling their audiences that they should be on “T” even if their doctor disagrees. This fits with the Make America Healthy Again movement, which has made distrust of conventional medicine conventional. Indeed Robert F. Kennedy junior, the health secretary, has set aside his habitual scepticism of injections to go on TRT as part of an “anti-ageing protocol”.

According to the American Urological Association, a quarter of the patients receiving TRT last year did not have their testosterone levels checked before starting treatment. Of those who were given TRT, a third were not in fact testosterone deficient. Akanksha Mehta, a doctor at Emory University, says she turns away almost 50% of the men who come asking for it; Gameday treats almost everyone.

How bad is it for people who don’t need testosterone to be on it? Compared with other drugs it is relatively safe, as long as it is not taken in body-building doses. A big clinical trial published in 2023 found that taking testosterone does not increase the risk of prostate cancer or heart attacks, as was thought. But it can cause infertility, if another hormone is not given alongside it. Doctors often see young men who come in at “supraphysiological” levels who do not know that they have made themselves infertile. “There is a lot of anger,” says Ms Mehta. Mr Khera, the Houston doctor, reckons that in most cases he can restore fertility back to 25% of a patient’s baseline. But “when someone drops down that low it can be an issue”, he says.

The men’s clinics also vary in their quality of care—and the quality of drugs. Online retailers like Hone, Hims, Maximus and DudeMeds do not require in-person check-ups and often get patients hooked on subscriptions. Some clinics require multiple diagnostic blood tests, following medical standards; others do not. Gameday aims to “optimise” how men feel, and argues that men within the normal range can still benefit from treatment. Many clinics, with exceptions like the Low T Center chain in Texas, get their testosterone supply from compounding pharmacies rather than pharmaceutical firms. That means that the drugs are cheaper—TRT is rarely covered by insurance—but also not approved by the government’s Food and Drug Administration. Compounded testosterone is more likely to be contaminated and can fluctuate in potency per dose. Getting the safest stuff has also become harder. Pfizer, a big domestic supplier, recently reported a shortage of testosterone due to rising demand.

The majority of testosterone businessmen your correspondent spoke to said that they were doing things right, but others were dragging the industry into shady territory. Mr Burt of Gameday Buckhead says that making money from people’s health, as all ordinary doctors do, is in itself “an ethical balancing act” but that “doesn’t mean we should be more criticised than any other profession”. Like ketamine, testosterone is a Schedule III drug with a robust black market. In recent years customs agents have seized large caches of it at America’s borders. “There is a massive demand and it’s going to get met,” Mr Burt explains. It’s just a matter of whether it’s met at a clinic or at the gym. ■

The Americas | A losing battle

Brazil is bashing its patron saint of the environment

Congress is bulldozing environmental laws. Marina Silva wants to stop it

Silva needs no mansplainingPhotograph: Alamy

Jul 9th 2025|6 min read

Listen to this story

When Marina Silva resigned as Brazil’s environment minister in 2008, she was an international rock star. Deforestation in the Amazon had plummeted by 50% during her five-year tenure. She had been showered with awards and included on lists of influential thinkers. She was also admired for her tenacity. Brought up poor and illiterate as one of 11 siblings on a rubber plantation, Ms Silva went on to graduate from university, be elected as Brazil’s youngest senator and forge Brazil’s climate policies. Even her resignation, in protest at large infrastructure projects in the Amazon, seemed to bolster her integrity.

Now Ms Silva is under attack in Brazil. Having returned to the helm of the environment ministry in 2023, on July 2nd she was summoned before a committee in the lower house of Congress to testify about deforestation. Lawmakers hurled insults at her for almost seven hours. They called her “inelegant” and “a disgrace”, compared her to terrorists and told her to resign. In a previous exchange, senators had told her she “should know her place” and that she did not deserve respect.

Such chauvinist language is nasty, and reflects the state of environmental discourse in Brazil today. Since Ms Silva’s last stint in office, Congress has become both more powerful and more beholden to agribusiness and fossil-fuel lobbyists. The government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula) is desperate for cash. As his relationship with lawmakers sours, he is increasingly loth to stand in their way.

Those attacking Ms Silva want to pass a bill that would dismantle many of Brazil’s environmental regulations. It would exempt infrastructure, mining and farming projects that have a “small or medium-size impact” from having to carry out an environmental-impact assessment, putting them on a fast track instead. In some cases developers would be allowed to judge the impact of their own works. Projects the government deems strategic would automatically qualify for simpler licensing. The World Wide Fund for Nature, a charity, calls it “the biggest setback in Brazilian environmental legislation in the last 40 years”. A final vote on the bill could come as soon as July 16th.

The impulse to simplify Brazil’s licensing laws is reasonable. The country has 27 states and over 5,000 municipalities, which sometimes enforce their own rules. This is a pain for businesses that operate across different regions. Yet the proposed law would gut environmental protections and offer new avenues for corruption. “Just because a project is deemed strategic for the government does not mean the environmental impact disappears,” says Ms Silva. It could also create legal uncertainty. Brazil’s top court has ruled that projects with a medium-size impact should not qualify for fast-track licensing. Flávio Dino, a judge on the Supreme Court, has said he expects the bill to be contested.

Photograph: Getty Images

That the bill could pass while Lula is president frustrates environmentalists. He took office in 2023 promising to tackle the illegal ranchers, loggers and miners that proliferated under Jair Bolsonaro, his far-right predecessor. He beefed up IBAMA, the environmental regulator. Deforestation fell. In November he will try to bolster his credentials when Brazil hosts the COP30, the UN’s annual climate conference. Lula “will need to make a choice between his environmental promises and pleasing Congress”, says Marcio Astrini of the Climate Observatory, a network of charities in Brazil. “He can’t have both.”

Three forces are undermining Ms Silva. The first is that Congress has become emboldened. In the past decade Brazil’s legislature has given itself vastly greater spending powers. In 2015 lawmakers’ amendments to discretionary spending in the federal budget, which amounts to some $40bn a year, represented less than 2% of the total. Today such “earmarks” account for a quarter of non-mandatory spending—far higher than the average in the OECD, a club of rich countries. Representatives demand pork in exchange for backing laws. In June a bill that will regulate offshore wind energy only passed in Congress after lawmakers forced Lula to include unrelated subsidies in the draft.

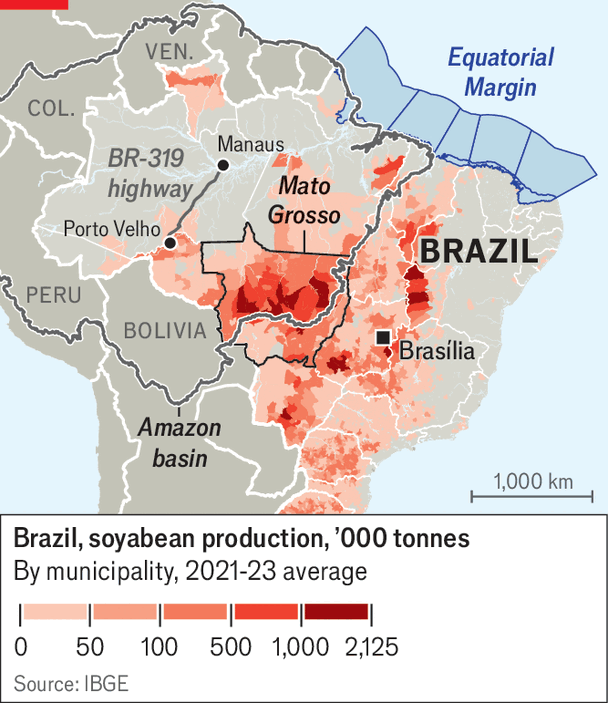

As it has gained power, the composition of Congress has shifted rightwards. Though Mr Bolsonaro lost the presidential election in 2022, his party and centre-right groupings swept the legislature. The rural caucus now comprises almost two-thirds of lawmakers in both houses. The lobby is particularly strong at a local level. Lawmakers in Mato Grosso, Brazil’s soyabean heartland, are trying to have parts of the state reclassified as tropical savannah instead of Amazon. This would let farmers raze 65% of trees on their land, instead of only 20%. Governors elsewhere are gunning for looser licensing laws. This would allow for the completion of the BR-319, a once-abandoned 900km (550-mile) highway that cuts through pristine jungle. Lula has promised to finish much of the road by the end of his term.

Map: The Economist

Brazil’s oil lobby has also gained clout. Prospectors believe the country’s northern coastline is rich in crude oil, in an area called the Equatorial Margin (see map). But because it lies near the mouth of the Amazon river, IBAMA has prohibited drilling there. Lula and several of his ministers want to exploit it, and think the licensing law could help. If this happened, Brazil could become the world’s fourth-largest producer of crude by 2030, up from seventh today. On June 17th the national oil agency put 172 exploration blocks up for auction, including some near the Amazon basin. The government plans to offer more oil concessions this year, which it hopes will raise some $4bn.

The final obstacle is the government’s fragile finances. The IMF says public debt is on course to hit 92% of GDP this year, up from 60% in 2013. Much of this borrowing happened under Lula’s predecessors. Yet he is not helping. Without accounting trickery, the government will miss its fiscal goal of reaching a primary surplus of 1% by 2026. Lula has ramped up social spending and raised the minimum wage. The Senate is set to approve his plan to exempt people who earn up to 5,000 reais ($920) a month from income tax. That will cost around $5bn a year in lost revenue. Easy oil money is thus particularly appealing.

Every cloud

And so Brazil’s environmental movement is squeezed. Yet Natalie Unterstell of the Talanoa Institute, a think-tank in Rio de Janeiro, sees a silver lining. Only 34 of the 172 blocks put up for auction found takers. Even the union of oil workers did not back licensing sites near the mouth of the Amazon river, which Brazil’s public prosecutor tried to suspend. Mr Astrini is blunt. If the licensing bill passes, “We will not stop fighting for the environment. We will just hire more lawyers.” ■

Middle East & Africa | Assassin’s creed

Got an enemy? Hire a killer

In South Africa, contract murders are spreading from gangland into wider society

Illustration: Gregori Saavedri

Jul 10th 2025|Cape Town|4 min read

Listen to this story

In late June a dozen soldiers from a South African elite special-forces unit appeared in court in Johannesburg. They were charged with the murder of Frans Mathipa, a police detective. He was shot twice in the head from a moving car while driving north from Pretoria in 2023.

The detective’s murder is a special case: at the time he was shot, he was investigating the unit whose members have been charged with his killing. Yet it is also part of a grim trend. Having inconvenient people bumped off is disturbingly common in South Africa. What began as a way to settle drug disputes or turf wars between gangs has become a service industry with a varied customer base. Targets range from teachers to civil servants and politicians.

Contract killings are still a small share of all murders in the country of 64m people, where an average of 72 people were killed every day in 2024. Yet there has been a sharp rise since 2015, says Rumbi Matamba, who tracks these murders for the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC), an NGO. There are now at least ten a month, reckons Ms Matamba, up from around four a month in the early 2010s. She says the rise is mostly the result of the increasing availability of both guns and hitmen, known as izinkabi in Zulu. Legitimate jobs are scarce and killers are rarely caught. As a result, many young men who started out as apprentice assassins in gangs are now willing to moonlight for other clients.

The first time he killed someone for money it took him two days to work up the courage, says one teenage killer. He shot three times, missing once, “because it was the first time, and I looked away”. The next four murders came easier. “After two or three times you can look at someone’s face,” he says. He reckons he may survive in the job for a year or two. The most he has ever been paid for a hit was 400 rand ($23). That is at the low end of the scale. Murders that require extensive surveillance of the intended victim, or where the victim has bodyguards, cost more.

The proliferation of hitmen is one factor in the spread of assassinations. Another is impunity. One study estimates that police solve as few as one in ten political assassinations. Partly that is because the criminal networks are so sophisticated. Triggermen rarely know who commissioned the hit, says Mark Shaw, author of a book on assassinations. Both middlemen and izinkabi are expendable if powerful clients want to cover their tracks. Yet police are also sometimes complicit, either by renting out their uniforms or body armour to criminals, or by offering themselves as killers for hire. Of the 337 people arrested by an assassination task force since 2016, 47 were members of the police. The task force was disbanded earlier this year; on July 6th a senior policeman broke ranks and accused the minister of police of meddling in its investigations (the minister denies the allegation).

Most contract killings are still linked to disputes over lucrative minibus routes, which are controlled by mafia-like networks, and other organised crime. Together these account for around two-thirds of the total, according to GI-TOC. About a quarter are politically motivated, often linked to rivalries within the African National Congress, the main governing party, as candidates seek to eliminate rivals higher up on election lists or gain control of lucrative municipal budgets.

The practice is beginning to seep into other areas of society. In 2021 the chief accountant in Johannesburg’s provincial health department was murdered as she was preparing to expose a big accounting fraud in a local hospital; her death set the investigation back by years. In 2017, the head teacher of a school in KwaZulu-Natal province was shot in front of her history class; school governors barred staff from applying to fill the vacancy because they suspected them of having been involved.

When politicians and civil servants fear for their lives for doing their jobs, the functioning of the state is compromised. That is even more true when lawyers, politicians or members of the police like Mathipa are targeted. Mr Shaw worries that hitmen could increasingly be paid to kill more senior politicians, police officers or judges, further undermining South Africa’s already embattled institutions.

The arrests in the Mathipa case are a welcome sign that the South African state is not entirely powerless to deal with the threat. Yet real justice is rare. The men who killed the accountant in Johannesburg were eventually convicted. Their paymasters remain in the shadows. ■

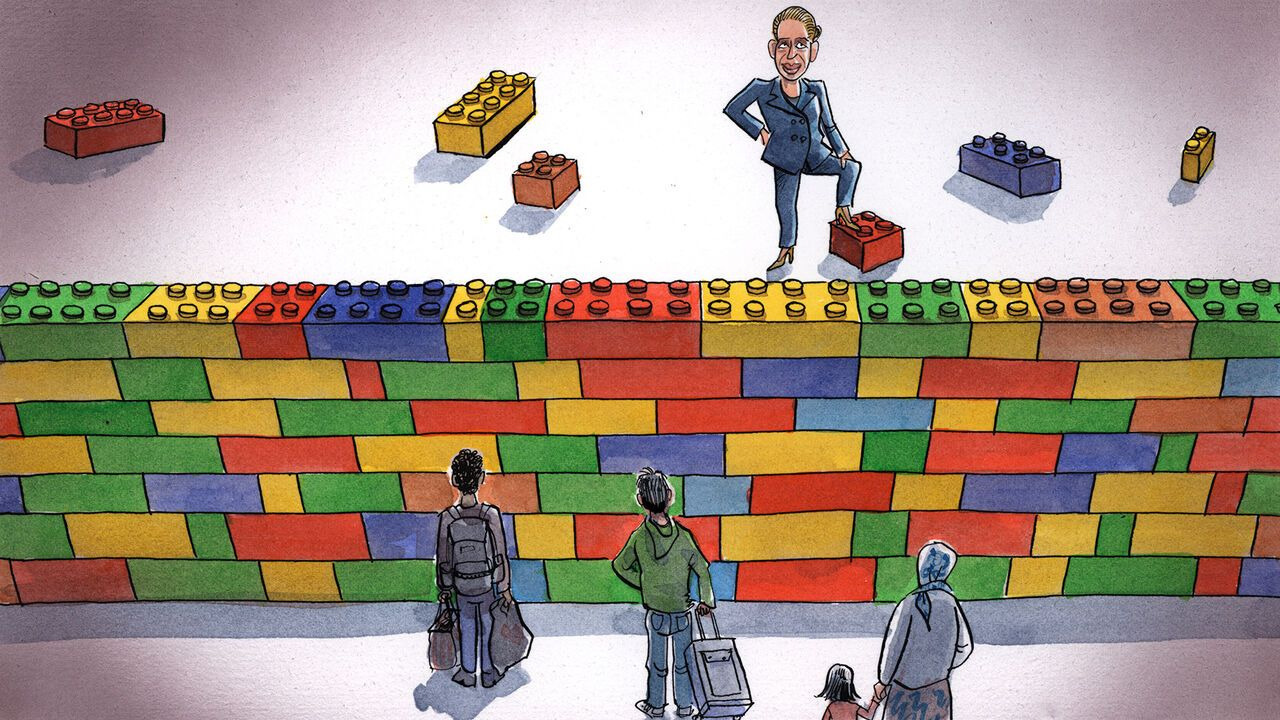

Europe | Charlemagne

Denmark’s left defied the consensus on migration. Has it worked?

Building walls, one brick at a time

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Jul 10th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Venturing beyond the ring road of just about any western European capital, far from its museums and ministries, often means encountering a landscape that mainstream politicians prefer to gloss over. Many suburbs are havens of familial peace. But others are the opposite: run-down dumping grounds into which societies shunt the immigrants whom they have failed to integrate. In the unloveliest banlieues surrounding Paris, Berlin or Brussels, criminality—whether petty, organised or drug-related—is often rife. Social indicators on education or employment are among the nation’s worst. Ambitious youngsters looking to “get out” know better than to put their real home address on their CVs.

These are uncomfortable facts, so much so that to point them out is to invite the disgust of European polite society. Whether in France, Germany, Italy or Sweden, parties of the hard right have surged as they—and often only they, alas—persuaded voters that they grasped the costs of mass migration. But the National Rally of Marine Le Pen in France and Giorgia Meloni’s post-fascist Brothers of Italy have an unexpected ally: Denmark’s Social Democrats, led by the prime minister, Mette Frederiksen. The very same party that helped shape the Scandinavian kingdom’s cradle-to-grave welfare system has for the past decade copy-pasted the ideas of populists at the other end of the political spectrum. Denmark is a generally well-run place, its social and economic policies often held up for other Europeans to emulate. Will harsh migration rhetoric be the next “Danish model” to go continental?

Ms Frederiksen, who served as party leader for four years before becoming prime minister in 2019, did not pioneer the migrant-bashing turn. Like most western European countries, Denmark had welcomed foreign workers and some refugees from the 1960s on. The tone shifted as early as the early noughties, even more so after an influx of Syrian asylum-seekers reached Europe in 2015. While Germany showed its kind side—the then chancellor, Angela Merkel, asserted with more hope than evidence that “we can manage this”—Denmark fretted that a far smaller number of arrivals might undermine its prized social arrangements.

The Danish left’s case for toughness is that migration’s costs fall overwhelmingly on the poor. Yes, having Turks, Poles or Syrians settle outside Copenhagen is great for the well-off, who need nannies and plumbers, and for businesses seeking cheap labour. But what about lower-class Danes in distant suburbs whose children must study alongside new arrivals who don’t speak the language, or whose cultures’ religious and gender norms seem backward in Denmark? Adding too many newcomers, the argument goes—especially those with “different values”, code for Muslims—challenges the cohesion that underpins the welfare state.

For a place with a cuddly reputation, Denmark has been cruel to its migrants. Authorities in 2015 threatened to seize asylum-seekers’ assets, including family jewels, to help pay for their support. Benefits were cut, as was the prospect of recent arrivals bringing in family members. Being granted permanent residency, let alone Danish nationality, takes longer than almost anywhere else. And it is far from guaranteed: those offered refuge are afforded protection only as long as conflict in their home country rages, their status reviewed every year in some cases. Somalis and Syrians once settled in Denmark are among those who have been asked to head back to a “home” their children have never known.

In 2021 it was proposed that newcomers seeking asylum in Denmark should be processed in Rwanda instead, a plan that fizzled. A law passed by Ms Frederiksen’s predecessor, but which she enthusiastically carried forward, cracks down on “ghettos”, now known as “parallel societies”: estates housing lots of folks with “non-Western backgrounds”. If crime, unemployment or other metrics are too high, failure to reduce them (or the “non-Western” resident share) can result in their being razed or sold off.

The upshot of the left’s hardline turn on migration has been to neutralise the hard right. Once all but extinct, it is still only fifth in the polls these days, far from its scores in the rest of Europe. For good reason, some might argue: why should voters plump for xenophobes when centrists will deliver much the same policies without the stigma? Either way, that has allowed Ms Frederiksen to deliver lots of progressive policies, such as earlier retirement for blue-collar workers, as well as unflinching support for Ukraine. The 47-year-old is one of few social-democratic leaders left in office in Europe, and is expected to continue past elections next year. Before that, she has a megaphone to pitch her unyielding approach to migration to the rest of the EU: Denmark holds the bloc’s rotating presidency until the end of the year.

To tolerate or not to tolerate

Denmark’s near-consensual diagnosis that the poor are left to pick up the pieces of botched migration policies is worth pondering. But this recent visitor to Copenhagen left with an uneasy feeling. Immigrants and their descendants make up about 1m of Denmark’s 6m-strong population. The ugly upshot around limiting immigration—however noble the motives—is that it seems acceptable to be nasty about immigrants. As a class they are spoken of as a “threat”, an inconvenience to be dealt with. Disdain for Muslims seems tacitly endorsed by officialdom, as if each were a potential rapist or benefits cheat. Refugees with proven fears of persecution are expected to learn Denmark’s language and adopt its customs—but face being kicked out at any minute. Such an us-versus-them approach is corrosive to a country’s sense of citizenship. How can people embrace a society that holds them in contempt? Denmark may have done a better job than others of grasping that migration comes with costs. But it risks shattering the social cohesion it is trying to preserve. ■

International | The Telegram

The 19th century is a terrible guide to modern statecraft

A world carved up between Presidents Trump, Xi and Putin would be unstable and unsafe

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Jul 8th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

SOME 120 years on, few remember the outrage provoked by the awarding of the Nobel peace prize to Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th American president and, to his critics, a might-makes-right, America First bully. That fuss offers lessons for the present.

Roosevelt saw stability in a world carved into spheres of influence that balanced the interests of big powers. He earned his 1906 Nobel—the first won by an American—by brokering a peace treaty that rewarded Japan for a war launched on Russia without warning. Morality was not his guide. Roosevelt was “thoroughly pleased” when Japan sank much of Russia’s navy, for he saw Russia as the main obstacle to American ambitions in Asia. Still, he aimed to avoid Russia’s total defeat. Once safely weakened, Russia would be a useful check on Japan’s rise. Envoys from both powers were summoned by Roosevelt to cut a deal in which Russia handed swathes of modern-day China to Japan: the “balance of power” at work. In this chilly system, perfected in 19th-century Europe, large countries seek security by limiting the ability of one power to dominate all others. The same system seeks to limit conflicts by paying heed to the core interests of big states, especially in their neighbourhoods. Small countries do what they are told.

Liberal-minded Europeans were appalled by Roosevelt’s Nobel. They called him a “military mad” imperialist. They recalled his assertion in 1904 of an American sphere of influence from the Arctic to Cape Horn, including an “international police power” to intervene anywhere in the western hemisphere. Roosevelt’s declaration built on the Monroe Doctrine, a 19th-century warning to European colonial powers to stay clear of the Americas. Roosevelt meant what he said, sending troops to foment revolution in Panama, and to grab territory there for an American-owned canal.

President Donald Trump’s fans detect thrilling parallels, and not just because Mr Trump covets his own Nobel prize. To America Firsters, spheres of influence are a smart response to a world of problems that America cannot fix, and should not have to.

Mr Trump certainly seems to take a 19th-century view of the western hemisphere. He wants America to own ports at each end of the Panama Canal, which currently belong to a Hong Kong-Chinese conglomerate. And he is hostile to Chinese-funded infrastructure across Latin America. In 1895 it was Britain that angered America by trying to build a telegraphic-cable station on an island near Brazil, and by claiming land at the mouth of the Orinoco river in Venezuela. President Grover Cleveland’s secretary of state successfully browbeat his British counterpart into backing off, explaining: “Today the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law.” As for Greenland, American governments first talked of buying that cold island in 1867, though Mr Trump’s preferred excuse—that America must keep Greenland’s minerals out of Chinese hands—is new.

If Mr Trump cedes a sphere of influence to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, MAGA types would stand ready to defend him. America Firsters agree with Mr Trump that Russia had a right to feel menaced by NATO enlargement. Jump to Asia, and some Trump loyalists even sound ready to accommodate China’s core interests. Donald Trump junior, the president’s eldest son, wrote in February that an America First foreign policy should seek “a balance of power with China that avoids war”, by “avoiding poking the dragon in the eye unnecessarily”.

During the cold war, American- and Soviet-led blocs amounted to spheres of influence. After the USSR fell, both Democratic and Republican administrations repudiated such spheres as deplorable artefacts of the past, calling instead for a liberal world order, open to all. Mr Trump’s secretary of state, Marco Rubio, sounds less definitive. In March he was asked whether Mr Trump’s aim is an understanding with China, whereby the two powers avoid one another’s backyards. Rather than denounce the very notion as illegitimate, Mr Rubio replied that “we don’t talk about spheres of influence” because America is “an Indo-Pacific nation” with friends and interests in the region.

China denies wanting a sphere of influence, chiding Westerners with a “bloc mentality” for trying to divide the world. For all that, Xi Jinping in 2014 rejected the meddling of outsiders, saying: “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia.”

Speak loudly and wave a big stick around

In fact, nostalgia for spheres of influence is misplaced. Such compacts would not bring stability today. The 1880s were simpler in several ways. An empire could feel (somewhat) secure once it controlled its own set of key resources, such as coal, iron, oil, copper, rubber and grain, as well as guaranteed colonial markets for its industrial exports. Today, indispensable inputs are generated by supply chains spanning many continents, and will be for years. What is more, the contests to develop certain future technologies, from artificial general intelligence to quantum computing, resemble winner-takes-all arms races. Until those races are won, neither America nor China can feel safe in its own economic sphere. Compared with a century ago, lots of mid-rank countries are too strong to be forced to comply, even assuming that great powers could agree where new blocs begin and end. Poland and South Korea have tragic histories of being divided by others. Today politicians in both countries wonder aloud if they need nuclear arsenals.

Mr Trump is no Teddy Roosevelt. If he were a master of Rooseveltian statecraft that tempered spheres-of-influence policies with balance-of-power realism, he would fear a Ukraine armistice that dangerously strengthens Russia. Were he focused on denying China hegemony in Asia, he would pick fewer pointless fights with allies in that region, and plan trade wars with China less impulsively. Cynicism without skill is no way to put America First. ■

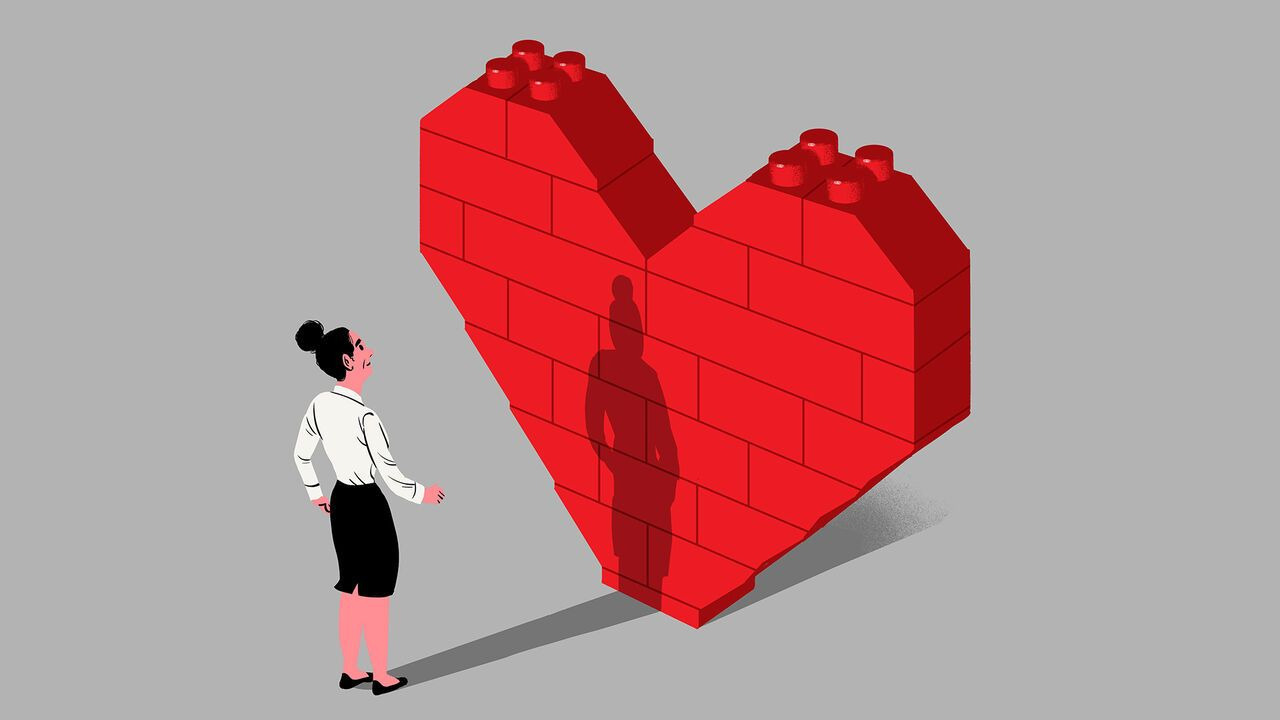

Business | Bartleby

On Lego, love and friendship

Human relations are a useful way to think about brands

Illustration: Paul Blow

Jul 7th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

There is a locked room in Lego’s corporate museum, in Billund in Denmark, which is called the Vault. It is a large space, filled with shelves that are arranged in chronological order, starting in 1958 and stretching towards the present day. Between them, the shelves contain around 10,000 sets of Lego.

The Vault is used by the toymaker’s designers as a source of inspiration, but its effect on first-time visitors is what makes the room remarkable. It’s impossible not to seek out sets from your own childhood, not to be drawn back to an earlier version of yourself and, for lots of people, not to well up. We thought about having Kleenex as a sponsor, says Signe Wiese, an in-house historian.

Visiting Lego’s vault is a chance to experience the emotional power of a much-loved brand (you can hear more in this week’s final episode of our Boss Class podcast). Marketing experts have a whole taxonomy to describe the ties that bind consumers and brands. In a recent review of the literature, Claudio Alvarez, Meredith David and Morris George of Baylor University identify five types of connection that have been the subject of concerted study.

The feeling that every marketing manager dreams of eliciting is “brand love”. This goes well beyond a belief in the quality of a firm’s products to include things like emotional attachment, feelings of passion, frequent use, a strong sense of identification with a brand and more. It’s not quite doodling a business’s name and yours with a love-heart, but it’s not far off.

The flipside of brand love is “brand hate”, a reaction that might reflect bad experiences with a product, a strong dislike of a brand’s values or simply a rivalry with a loved brand. A diverting piece of research by Remi Trudel of Boston University and his co-authors looks at how consumers choose to dispose of products, and finds that people who strongly identify as Coca-Cola drinkers are more likely to recycle a Coke can and throw a Pepsi one in the rubbish; the reverse is true of Pepsi fans.

The three other types of consumer-brand connection identified by Mr Alvarez and his co-authors are “communal relationships”, in which people feel a sense of obligation or concern for a brand (local stores can often fit into this category); “brand addiction”, often characterised by uncontrollable urges to buy a firm’s products and services; and “brand friendships”, to denote positive feelings that fall somewhere short of love.

These are the five types identified in the literature review, but the analogies between humans’ relations with each other and with brands can be extended in all sorts of directions. Researchers use the term “brand flings” to describe shorter-lived, intense interactions with brands, often in zeitgeisty industries such as fashion. “Brand flirting” involves a little dabbling with a competitor of your preferred brand; it can redouble your liking for the original. Friendships have subcategories, too: best friends, casual friendships and so on.

Some of this taxonomy can feel a bit forced. You’re going shopping, not joining an orgy. Brands cannot reciprocate feelings. But the idea of gradations of attachment rings true; how people feel about a brand determines their behaviour. Vivek Astvansh of McGill University and his co-authors found that people are more likely to report safety incidents when they believe a brand is well-intentioned than when they do not. The reason? They want to provide feedback that can help it to solve the problem.

Lego elicits a depth of emotion that feels like brand love. But Mr Alvarez wouldn’t put it in that category, because most adults do not continue to have frequent interactions with the products. It’s more like a childhood friend, he says, one that depends on the trigger of nostalgia to cause a wave of warm feelings.

Such distinctions are not just academic. Lego’s bosses, for example, make no bones about the fact that they have a limited window early in a child’s life to form a bond that can cause them to shed tears in a room in Billund decades later. If managers know what kind of connection a brand is likely to have with its customers, the bricks of a marketing strategy will fall into place. ■

Business | Schumpeter

A CEO’s summer guide to protecting profits

America’s bosses are sharpening their axes

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jul 10th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

MID-JULY is the time to bare it all. On the beach, this involves swimwear that, au fait with the latest fashion, varies in skimpiness from extreme to disturbing. In the boardroom, it consists of a ritual of corporate exhibitionism known as the summer earnings season. Results from the second three months of the year will trickle out over the next few weeks. Back in April it looked on course to be a distinctly awful quarter. President Donald Trump had just launched his trade war, sending stockmarkets down and bond yields up. Bottom lines were imperilled by rising costs and slowing economic growth. Think walking around in tiny Speedos makes you feel naked? Try fielding analysts’ questions about plunging profits on an earnings call.

In the event, bosses have had little to feel bashful about. Mr Trump chickened out in the face of market forces and promptly paused most of his tariffs for 90 days. Bond vigilantes retreated. The S&P 500 index of American big business has recouped all its losses and then some. Yes, the average forecast for its constituents’ second-quarter earnings growth has declined, from 9%, year on year, at the end of March to 5%, according to FactSet, a data provider. Nonetheless, many bosses will be able to parade record profits over the coming weeks.

Even so, they may experience some residual discomfort when asked about what comes next. Pressure on profits is building. Although Mr Trump has extended the tariff pause until August 1st, he has told Uncle Sam’s trading partners to brace for more levies. On July 8th the price of copper futures in America jumped by 13% after the president threatened a 50% tariff on the red metal. Days earlier he had signed into law a budget bill that will add perhaps $4.5trn to public debt, which may raise borrowing costs for everyone eventually (and pronto if bond traders stir).

Companies have little control over the cost of imports and of debt. They can, however, contain that of labour. In an effort to reassure investors, many have been telegraphing just such containment lately. On July 2nd Microsoft said that it would lay off 9,000 workers, or about 4% of the software giant’s total, on top of the 6,000 let go in May. That month Walmart told employees to prepare for 1,500 job cuts. In June BlackRock, Citigroup, Disney and Procter & Gamble all carried out “simplification”, “strategic realignment” or other euphemisms for sackings.

So far this year American companies have signalled a total of 439,000 redundancies, according to Challenger, Gray & Christmas, an outplacement firm. In the same period last year the figure was below 400,000. On July 2nd a closely watched jobs report from ADP, an HR firm, revealed that American businesses shed a net 33,000 workers in June. Official figures released the following day painted a rosier picture, but chiefly thanks to growth in public-sector and health-care payrolls.

Corporate employees should brace for more terminations. If innovation is America Inc’s mightiest superpower, ruthlessness in keeping its workforce lean comes a close second, especially next to the cuddlier capitalisms found in places like Europe or Japan.

On first glance, corporate America does not immediately look more pink-slip-happy than businesses in other rich economies. Three-quarters of S&P 500 firms saw their workforces shrink in at least one year over the past decade, identical to the share of Europe’s STOXX 600 index that reported such a decline. The index-wide workforce fell in nine of the past 24 years in Europe and seven times in America. One in four large European companies has a smaller workforce today than it did ten years ago, compared with just one in five American counterparts.

The big difference, of course, is that American businesses have been trimming nearly as much fat as European ones while growing much more robustly. Between 2014 and 2024 aggregate revenues for the S&P 500 increased by just over a fifth, after adjusting for inflation. For the STOXX 600 they contracted by the same amount. Sales outpaced employment at more than half of the American blue-chip companies. At 27 of them turnover rose even as the workforce diminished. By comparison, revenues grew more slowly than payrolls at two-thirds of large listed European firms.

The tendency to prune workforces whenever the opportunity arises is especially pronounced in America’s most go-getting sector. Since 2016 combined annual sales dipped just once for the S&P 500’s information-technology champions, whereas their total workforce was cut four times. Meta had 12,000 fewer techies at the end of last year than at its peak of 86,000 in 2022. On average, they generated $2.2m in revenue each in 2024, up from $1.4m three years ago. In January Mark Zuckerberg, Meta’s boss, channelled his inner Jack Welch by vowing to rank employees and yank the worst 5% of performers as he transforms his social-media empire into an artificial-intelligence (AI) powerhouse.

Computer says you’re fired

Advances in AI, and especially semi-autonomous AI agents, promise to hand bosses an even bigger axe. Chief executives cannot wait. In April Tobi Lütke informed his staff at Shopify, a maker of e-commerce software, that before asking for more people or more money, teams “must demonstrate why they cannot get what they want done using AI”. Last month Andy Jassy told Amazon’s white-collar employees that AI will reduce the tech titan’s total corporate workforce in the next few years.

When the next downturn does hit America Inc, as sooner or later it will, such pronouncements will multiply. Businesses can use recessions, when lay-offs are more excusable, to adopt labour-saving technologies. And even if AI does not save all that much labour, it provides convenient cover for CEOs seeking to slim down their workforces. Anything to avoid profitless nudity. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

Want to be a good explorer? Study economics

The battle to reduce risk has shaped centuries of ventures

Photograph: Alberto Miranda

Jul 10th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Deep in Zambia’s Copperbelt province, explorers from Kobold Metals are testing the ground for a new mine shaft. Although the arc of copper running through central Africa was first mapped by Victorian explorers and was mined by a colonial British firm, the search for deposits has been only occasionally fruitful in the years since. Kobold’s discovery is the biggest in a century. Born in California and backed by Bill Gates, the company uses everything from ancient maps to artificial intelligence in order to learn about what lies beneath the ground. Perhaps its biggest idea, though, is an economic model, pioneered at Stanford University, that helps process vast reams of information. It guides where Kobold drills, the most important decision for any miner.

The idea of a purely scientific explorer, financed by maverick philanthropists, is appealing. In reality, ever since the Renaissance the vast majority of ventures have been financed by companies and governments with an eye on profit. As with more typical projects, investors want to estimate, and then reduce, risk—in much the same manner as the risk-management department of a modern bank. Sailing to foreign lands, trekking to new wildernesses and excavating underground reserves is extraordinarily expensive. It is also fraught with uncertainty. Companies such as Kobold are just the latest to do battle with the unknown.

At best, early financiers were able to support those who returned with evidence of success, even if flimsy. Unfortunately, one batch of treasures offered little certainty of finding a second or third. Aside from the ever-present threat of disease and storms, few explorers understood the resources they sought to extract. Riverbeds moved, populations migrated, rockfaces crumbled.

In the 17th century financiers began to share risk more often. Even the most challenging ventures could purchase insurance through Lloyd’s Coffee House, an insurer that later became known as Lloyd’s of London, or on Amsterdam’s financial markets. Firms set up for the purpose of exploration, such as Hudson’s Bay Company and the East India Company, could not hedge against undefined and unknowable risks; they could, however, sell contracts that passed some of them on to others. By 1616 the Dutch East India Company was insuring its ships by selling sophisticated policies in which the buyer promised to contribute a share of the voyage’s cost should it meet an unfortunate end.

Governments and financiers also set out to map the world. The deluge of information this produced changed their investment decisions, allowing them to pick the most promising topographies for investigation. In the 1760s, for instance, American and British investors noticed iron-rich rocks on maps of the Andes drawn by Spanish conquistadors, spurring several expeditions.

Over time, maps, surveys and rock samples transformed exploration. The additional information was used to produce geological models—often the result of algorithms borrowed from statistical economics—that provided best guesses as to the location of economically viable mineral ores, thus representing predictions about maximum pay-offs. Mining companies did not spend their time attempting to estimate and reduce risk. Instead, they simply drilled in such places and hoped for the best.

Most modern resource exploration still suffers from very low success rates. Although at least 80% of the world’s valuable resources show no sign of existence above ground, some 85% of operating mines were dug as a result of surface observations. Much of what lies beneath the ground remains a mystery.

Kobold wants to return the focus to risk, by using new algorithms and data to reduce uncertainty. This includes quantifying how much geologists do not know—producing somewhat surreal numbers that indicate how likely a rock is to be somewhere. The idea, pioneered by Jef Caers, a geologist at Stanford who also designs economic models, comes from game theory. Faced with two options that hold an equal probability of success, the choice between them is arbitrary. When more information becomes available, it becomes less so. Yet you need to be convinced that the additional information is relevant, and that obtaining it costs less than just taking an arbitrary gamble.

Rock and a hard place

Suppose, for a minute, that you find yourself in charge of a directional drill with two prospective sites to excavate. How do you pick between them? A regular mining firm would make a bet on the rock core’s geology, and drill where it thinks valuable minerals are most likely to be found. Kobold holds several ideas about what could be going on beneath the surface at once. Its algorithms then create thousands of scenarios for each idea; any one could reflect the real rock core. The algorithms resemble those used by banks to ascertain the credit risk of countries.

How much is unknown about an area, and where is the uncertainty concentrated? Kobold can now answer both questions, along with the probability of finding a mineral in a particular place. The firm’s geologists then drill the hole that reduces the unknowns most drastically, rather than at the site where it expects to find the biggest prize. The idea is that, in time, it will come to know enough to pinpoint resources. As that will probably take fewer moves than a rival making a series of guesses about where the richest mineral seam lies, Kobold’s pay-off will be bigger.

After drilling just a few dozen holes, Kobold has dug millions of tonnes of copper in Zambia, outperforming local rivals. “If you could see inside the black box of everything under the Earth’s surface,” says Kurt House, the company’s chief executive, “you would be a perfect explorer.” Long dead Victorian gentlemen, who spent their lives seeking out mysterious and unknowable places, might disagree. Their financiers, however, would not. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Don’t invest through the rearview mirror

Markets are supposed to look forward; plenty of investors look back instead

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Jul 9th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

In a more predictable world, stocks would be easy to price. A share gives its owner claim to a series of cash flows, such as dividends and earnings. Investors would forecast the future value of each, then discount it to a present value based on prevailing interest rates, the riskiness of the cash flow and their own risk appetite. Add them all up, and that would be the stock’s price.

In the actual, radically uncertain world, things are rather more difficult. Few equity analysts, for example, even attempt to forecast earnings more than a few years into the future. But the “discounted cash flow” model is still useful. Divide stock prices by current earnings, and you get an indication of the discount rate the market applies to future cash flows. It turns out that this discount rate has historically been a reasonable, if imperfect, guide to the stockmarket’s long-run returns. A low discount rate (or, equivalently, a high price-to-earnings ratio) forecasts low returns, and vice versa. That is valuable information for investors considering, say, how much to save for retirement, or to allocate to stocks compared with other assets.

It might be surprising that such readily available measures help predict the future. The bigger surprise is that so many investors ignore them altogether. Similar forward-looking measures of expected returns are widely employed by academics and big institutional investors; indeed, they underpin many investment firms’ long-term forecasts of capital markets. Yet when it comes to individual investors, this reasoning is often turned on its head. Instead of looking forward, surveys consistently show that, as a group, they look back, expecting returns that are extrapolated from those in the past.

Think of it as investing through the rearview mirror. Such an approach says that if stock prices have soared recently, they will continue to do so. Admittedly, for most of the time since 2009, this has been a better prediction than the supposedly forward-looking ones. American share prices climbed for most of the 2010s, and price-to-earnings ratios with them, but the bull market just kept going. Trimming your stock allocation as valuations rose and the academics’ expected returns fell would only have cut your profits. Even after the bear market of 2022, prices began marching up again despite above-average valuations, and then rocketed. No wonder that, this year, retail investors are eager to buy shares whenever the market dips.

It is not just amateurs who look back rather than ahead. Stock analysts have strong incentives to accurately forecast the earnings growth of the companies they cover. They nevertheless tend to do so by extrapolating from past years, despite the fact that the true correlation between historical and future growth is negative. Theory suggests that the prices of options, a form of derivative contract, should depend on the volatility traders expect in the future. In practice, the volatility implied by foreign-exchange options often tracks the size of past jumps. Analysts at Goldman Sachs, a bank, find that over the past year this has led traders of foreign-exchange options to consistently underestimate future volatility. They have been wrongfooted by changing economic conditions and geopolitical uncertainty.

That points to the real problem with rearview-mirror investing: it is all very well until something smacks into the windscreen. Betting on a surging bull market continuing looked clever in the late 1990s, before the dotcom bubble burst, and again in 2021, before the following year’s crash. Both times, forward-looking measures would have noted exceptionally high valuations, forecast low returns and rightly cautioned against outsize investments in stocks. As animal spirits roared, such pessimism would have struck many investors as the very worst kind of downer—right up until the plunge began.

The rearview-mirror mindset, writes Antti Ilmanen of AQR Capital Management, a hedge fund, is most pronounced when such investors have recently “got it right”. It is most misleading when their success has come from rising valuations, since this is a trend that can readily go into reverse. And it is most dangerous when “the times they are a-changing”. For American stocks in particular, all three conditions are in place today. Those who have spent recent years investing through the rearview mirror have scored a victory over the ivory tower and some of the world’s grandest financial institutions. But it is probably time to start inspecting the road ahead.■

Science & technology | Hormones and mental health

Could hormones help treat some forms anxiety and depression?

Mental illnesses that do not respond to standard treatment could be hormone-driven

Illustration: Nathalie Lees

Jul 10th 2025|6 min read

Listen to this story

Their names are unknown but their pain is nonetheless evident. A user on Reddit, a social-media site, was “fairly close to being just another young man that killed himself because of depression”. On the website of Menopause Mandate, a campaign group, a woman tells of her grief “for the lost years where suicide seemed my only option”.

Both people described poor mental health that had resisted standard treatments. Both, eventually, found their ans-wers where psychiatrists seldom look—their low levels of sex hormones.

Mental illnesses resistant to treatment affect millions of people worldwide. Around a third of those seen by doctors for major depression, for example, are in this category. For some of these patients, an emerging consensus among scientists—bolstered by evidence from years of research on menopausal women—suggests that hormonal deficiencies could be causing their conditions.

From a biological point of view, this connection has been hiding in plain sight. The sex hormones oestrogen, progeste-rone and testosterone, all of which are produced by both men and women, are known to be potent governors of behaviour, mood and stress. Proteins sensitive to oestrogen are found scattered across many important regions of the brain, and studies have shown that this hormone can enhance memory formation, recall, decision-making and problem-solving. Progesterone and testosterone, meanwhile, exercise a calming effect via interactions with the brain region called the GABA-receptor complex. Other hormones, such as cortisol produced by the adrenal glands and those produced in the thyroid, also play a role in mood and behaviour.

It is evidence from medical practice, though, that is now leading scientists to look more closely at the role of hormones in mental health. Data from menopausal women, particularly from the past five years, have shown that they find relief from symptoms of depression and anxiety (and have therefore needed fewer antidepressants) because of hormone-replacement therapy (HRT). The evidence strongly suggests that a wider group of people—and middle-aged men and women in particular—could potentially benefit from similar hormonal treatments.

Start with men. The Endocrine Society, a scientific group, says that about 35% of men over the age of 45 have hypogonadism, a condition in which their testes produce little or no testosterone; it is rarer for those in their 20s and 30s.

There is a dearth of good data on dia-gnosis of hypogonadism rates but experts say it is widely underdiagnosed and undertreated. Men with low testosterone often report symptoms such as depression, irritability and cognitive impairment.

Even though testosterone-replacement therapy (TRT) is not in the standard toolkit for treating depression in men, some evidence suggests it may be useful—a meta-analysis of studies on almost 2,000 men in total, published in 2019, showed that TRT was associated with a reduction in the symptoms of depression.

In America the popularity of TRT has risen sharply since 2019, with many men with hypogonadism finding their mental health greatly improved after receiving it. The perception of TRT, however, has become muddied by sloppy prescribing practices and the aggressive promotion of testosterone as an easy solution for low energy, muscle growth or ageing.

Women in the run-up to menopause—a period known as perimenopause—are another group that may be missing out. Some experience serious mental-health problems. Last year researchers from Cardiff University published an analysis using data from UK Biobank, a research body, of almost 130,000 women who had gone through menopause and who had no history of psychiatric disorders. During perimenopause, the risk of major depression and bipolar disorder increased by 30% and 112%, respectively, compared with the risk of developing the illnesses during their younger reproductive years.