The Economist Articles for Aug. 1st week : Aug. 3rd(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.07.26조회수112 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Aug.1st week : Aug. 3rd(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Humanity’s next step

The economics of superintelligence

If Silicon Valley’s predictions are even close to being accurate, expect unprecedented upheaval

ul 24th 2025|6 min read

Listen to this story

FOR MOST of history the safest prediction has been that things will continue much as they are. But sometimes the future is unrecognisable. The tech bosses of Silicon Valley say humanity is approaching such a moment, because in just a few years artificial intelligence (AI) will be better than the average human being at all cognitive tasks. You do not need to put high odds on them being right to see that their claim needs thinking through. Were it to come true, the consequences would be as great as anything in the history of the world economy.

Since the breakthroughs of almost a decade ago, AI’s powers have repeatedly and spectacularly outrun predictions. This year large language models from OpenAI and Google DeepMind got to gold in the International Mathematical Olympiad, 18 years sooner than experts had predicted in 2021. The models grow ever larger, propelled by an arms race between tech firms, which expect the winner to take everything; and between China and America, which fear systemic defeat if they come second. By 2027 it should be possible to train a model using 1,000 times the computing resources that built GPT-4, which lies behind today’s most popular chatbot.

What does that say about AI’s powers in 2030 or 2032? As we describe in one of two briefings this week, many fear a hellscape, in which AI-enabled terrorists build bioweapons that kill billions, or a “misaligned” ai slips its leash and outwits humanity. It is easy to see why these tail risks command so much attention. Yet, as our second briefing explains, they have crowded out thinking about the immediate, probable, predictable—and equally astonishing—effects of a non-apocalyptic AI.

Before 1700 the world economy grew, on average, by 8% a century. Anyone who forecast what happened next would have seemed deranged. Over the following 300 years, as the Industrial Revolution took hold, growth averaged 350% a century. That brought lower mortality and higher fertility. Bigger populations produced more ideas, leading to yet faster expansion. Because of the need to add human talent, the loop was slow. Eventually, greater riches led people to have fewer children. That boosted living standards, which grew at a steady pace of about 2% a year.

Subsistence to silicon

AI faces no such demographic constraint. Technologists promise that it will rapidly hasten the pace at which discoveries are made. Sam Altman, OpenAI’s chief executive, expects AI to be capable of generating “novel insights” next year. AIs already help program better AI models. By 2028, some say, they will be overseeing their own improvement.

Hence the possibility of a second explosion of economic growth. If computing power brings about technological advances without human input, and enough of the pay-off is reinvested in building still more powerful machines, wealth could accumulate at unprecedented speed. Economists have long been alive to the relentless mathematical logic of automating the discovery of ideas. According to a recent projection by Epoch AI, a bullish think-tank, once AI can carry out 30% of tasks, annual growth will exceed 20%.

True believers, including Elon Musk, conclude that self-improving AI will create a superintelligence. Humanity would gain access to every idea to be had—including for building the best robots, rockets and reactors. Access to energy and human lifespans would no longer impose limits. The only constraint on the economy would be the laws of physics.

You don’t need to go to that extreme to conjure up AI’s mind-boggling effects. Consider, as a thought experiment, just the incremental step to human-level intelligence. In labour markets the cost of using computing power for a task would limit the wages for carrying it out: why pay a worker more than the digital competition? Yet the shrinking number of superstars whose skills were not automatable and could directly complement AI would enjoy enormous returns. The only people doing better than them, in all likelihood, would be the owners of AI-relevant capital, which would be gobbling up a rising share of economic output.

Everyone else would have to adapt to gaps in AI’s abilities and to the spending of the new rich. Wherever there was a bottleneck in automation and labour supply, wages could rise rapidly. Such effects, known as “cost disease”, could be so strong as to limit the explosion of measured gdp, even as the economy changed utterly.

The new patterns of abundance and shortage would be reflected in prices. Anything AI could help produce—goods from fully automated factories, say, or digital entertainment—would see its value collapse. If you fear losing your job to AI, you can at least look forward to lots of such things. Wherever humans were still needed, cost disease might bite. Knowledge workers who switched to manual work might find they could afford less child care or fewer restaurant meals than today. And humans might end up competing with AIs for land and energy.

This economic disruption would be reflected in financial markets. There could be wild swings between stocks as it became clear which companies were winning and losing winner-takes-all contests. There would be a rapacious desire to invest, both to generate more AI power and in order for the stock of infrastructure and factories to keep pace with economic growth. At the same time, the desire to save for the future could collapse, as people—and especially the rich, who do the most saving—anticipated vastly higher incomes.

Persuading people to give up capital for investment would therefore require much higher interest rates—high enough, perhaps, to make long-duration asset prices fall, despite explosive growth. Scholars disagree, but in some models interest rates rise one-for-one or more with growth. In an explosive scenario that would mean having to refinance debts at 20-30%. Even debtors whose incomes were rising fast could suffer; those whose incomes were not hitched to runaway growth would be pummelled. Countries that were unable or unwilling to exploit the AI boom could face capital flight. There could also be macroeconomic instability anywhere, because inflation could take off as people binged on their anticipated fortunes and central banks did not raise rates fast enough.

It is a dizzying thought experiment. Could humanity cope? Growth has accelerated before, but there was no mass democracy during the Industrial Revolution; the Luddites, history’s most famous machine-haters, did not have the vote. Even if average wages surged, higher inequality could lead to demands for redistribution. The state would also have more powerful tools to monitor and manipulate the population. Politics would therefore be volatile. Governments would have to rethink everything from the tax base to education to the protection of civil rights.

Despite that, the rise of superintelligence should provoke wonder. Dario Amodei, boss of Anthropic, told The Economist this week that he believes AI will help treat once-incurable diseases. The way to look at another acceleration, if it comes, is as the continuation of a long miracle, made possible only because people embraced disruption. Humanity may find its intelligence surpassed. It will still need wisdom. ■

Asia | When first class isn’t good enough

The new private jet pecking order

In oligarchic aviation China has just fallen behind India

Illustration: Owen D. Pomery

Jul 24th 2025|Mumbai|5 min read

Listen to this story

Life for Asia’s super-rich has its ups and downs. One industry, more than any other, provides a bird’s-eye view on their fortunes: the mind-boggling market for private jets. In recent years the number of posh private aircraft registered in China has dropped like a stone, in part because the Communist Party has taken umbrage against lavish displays of wealth. These days it is India’s rising rich who are snapping up sleek personal planes.

Private jet-makers have long gambled that Asia will deliver an outsize chunk of future growth. By one estimate, the value of private-jet sales in the continent will swell 7% a year to 2030. That compares with 4% annual growth worldwide and a mere 1% in America (already home to two-thirds of the world’s private-jet fleet).

For years it was Chinese demand that made brokers in the region rich. Chinese tycoons took to the skies in droves during the go-go years of the 2000s and 2010s. Their country still has more private jets than any of its neighbours, yet the lead has been dwindling. Between 2021 and 2024 the size of China’s fleet shrunk by a whopping one-quarter, to 249 jets, according to Asian Sky Group (ASG), a business-jet broker and consultancy.

Zero-covid rules preventing travel may have encouraged some of the jet junking. More important: Chinese magnates lost money to a property crash and to crackdowns by a ruling party that thinks entrepreneurs are too big for their boots. The number of dollar billionaires in China peaked at about 1,185 in 2021 (37% of the global total). Since then, the number has fallen by one-third.

A few years ago the Chinese government relaunched hoary campaigns that aim to stop party members, and anyone else with a public profile, behaving in ways that could be deemed extravagant. That has gone as far as banning alcohol at government functions and lambasting excessive flora in meeting rooms. Thus even people with lots of cash now worry about being seen spending it.

Hop across the Himalayas, however, and one finds a very different mood. Between 2020 and 2024 the number of private jets registered in India jumped by nearly a quarter to 168. The number of monthly private flights tripled to more than 2,400, higher than anywhere else on the continent). In the year to March 2025, four of the ten most popular private-jet routes in Asia were domestic Indian ones, connecting Mumbai to Delhi, Bangalore, Ahmedabad and Pune (a mere four-hour drive away). None of the busiest routes began or ended at a Chinese airport.

The good times in India started in 2021, says Vinod Singel, who back then was selling planes for Bombardier, a Canadian aircraft-maker. “That’s when I saw the real boom.” Private-jet firms once treated India as an afterthought. Now they organise polo matches to woo customers.

“A whole new wave” of super-rich customers has joined the market, says Nitin Sarin, a lawyer in aviation finance. “When I started out it was just the big boys” who bought private jets, he says, such as the people running India’s richest conglomerates. Now buyers come from construction, jewellery, pharmaceuticals and education. Many are from second- and third-tier cities. They “are done buying their Maybachs and Rolls-Royces”, says Mr Sarin.

High-flying Indians differ from their Chinese peers in the jets they buy. In China the market is a lot about “showing off”, says Dennis Lau of ASG. The thinking is: “[I can’t] turn up to my golf game in a jet that’s smaller than my competitor.” So Chinese buyers lean towards high-end aircraft that can go long distances, even if that is more than they require.

Indians more often buy practical models, and use their planes more intensively. In China it is easy to cover shortish distances on the ground using high-speed rail or pristine new highways. That is not at all the case in India. As for commercial flights, schedules in India are not yet deep enough to permit day-tripping to the small cities and factory sites that tycoons sometimes visit. Besides, “it’s not easy to fly commercially,” says Rohit Kapur, a broker and former president of the Business Aircraft Operators Association. “Try going into a lounge anywhere in India. There’s a queue of 500 people with their credit cards.”

Rich Indians are fiercer negotiators than their Chinese peers, brokers say. One tells of a colleague who met a Chinese client at a golf club in order to clinch the sale of a $65m jet. The buyer’s friend came by and decided on the spot to buy the same aircraft. In India, by contrast, even “top-level clients” haggle down to the last $5,000 on a $100m jet, says the broker: “Nobody splurges here.”

This hard-nosed bargaining looks a bit more reasonable once all the costs of ownership are totted up. Private jets go for between $3m and $100m, depending on their size, range and age. Taxes on them run at 28% (though most Indian buyers charter them out sometimes, which cuts the levy to 5%). For a $10m jet, fixed annual costs run at $1m-1.5m, not including charges for fuel, parking and landing fees.

If the market keeps growing, ordinary Indians will soon also get saddled with some of the costs. Private flights produce far more emissions per passenger than the commercial kind. They also jam up busy airports. India lacks small airfields of the kind other countries use for private jets. It has only about 300 airfields in total, compared with 16,000 in America.

As the number of airports grows—a government priority—so will the number of jets. Private charter services aimed at less pecunious millionaires are getting more common. The industry could expand swiftly using innovative business models borrowed from the West, such as on-demand aircraft charters and timeshares.

The Indian market does not seem hostage to the sort of government meddling that has lately weighed down planes in China. The main thing that could clip its wings, then, is a big economic downturn. If that happens, the super-rich—like everyone else—might just have to make some wrenching adjustments. In a recession, warns Mr Kapur, company jets “will be the first thing to go”. ■

China | Shamraderie

“Comrade” is making a comeback in China

Or so the government hopes

Illustration: Ben Hickey

Jul 24th 2025|Beijing|2 min read

Listen to this story

DURING THE decades when Mao Zedong ruled China, it was common for people to address each other as tongzhi: “comrade”. Like its English equivalent, the word has an egalitarian ring, as well as a hint of revolutionary fervour. But after Mao’s death in 1976, and the market reforms that followed, the term tongzhi started to feel a little dated. Less ideological greetings took its place: like xiansheng (“mister”), meinu (“beautiful woman”) and laoban (“boss”).

So it caused a stir when the People’s Daily, a Communist Party mouthpiece, published an opinion piece this month calling for the word tongzhi to return to everyday speech. Modern greetings can sound frivolous or phoney, the author complained. Some are even “sugar-coated bullets”, they warned, using a Maoist term for bourgeois customs that corrupt the working class. Better, then, to return to the greeting used “back when people were simple and honest”.

The party often tries to stoke nostalgia for the days of high socialism in order to bolster its support. In recent years local governments have encouraged “red tourism” at sites like Mao’s hometown to teach people about the history of the party (needless to say, they are given a version without all the bloodshed). Some firms send employees on “red” teambuilding courses where they dress up as guerillas from the 1930s and trek along muddy mountain paths. In 2015 party members, though not the general public, were told to call each other tongzhi again as a way of “purifying” political culture.

The term seems unlikely to make a comeback outside the party, however. For one thing, since the 1990s tongzhi has become a popular slang term for gay people, catching on because it sounded neither pejorative nor clinical, unlike most of the alternatives. For a time one of China’s biggest LGBT-rights organisations, based in the capital, was known as the “Beijing tongzhi Centre” (it closed in 2023 under political pressure).

But many people have criticised the idea for another reason. Since the death of Mao, China has become far richer—but the wealth has not been spread evenly. The country’s Gini coefficient, a common measure of income inequality, rose sharply in the 1990s and is now higher than that of America, according to official estimates. Inequalities have particularly started to sting as the economy has sputtered. “Who should you call tongzhi?” asked one person in a post on Weibo, a social-media platform. “Someone with the same rights, assets…work and salary. Those earning 2,000 yuan ($280) a month can hardly call those earning 20,000 yuan their tongzhi.” There is little sense of camaraderie between China’s haves and have-nots. ■

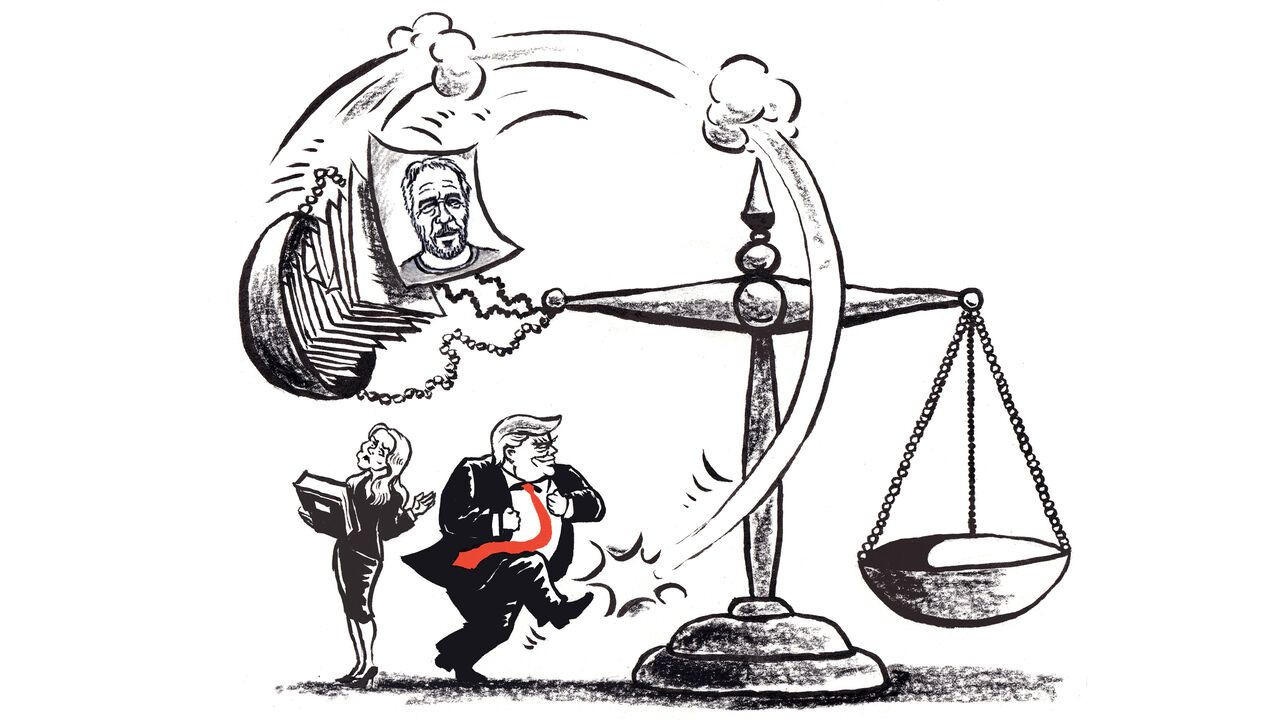

United States | Lexington

A little poetic justice for Donald Trump

The Epstein uproar has revealed an unexpected danger—for the president—of a Justice Department that seems partisan

Illustration: David Simonds

Jul 24th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

The “saddest thing” for Donald Trump, he said in an interview during his first term, was that as president he was “not supposed to be involved” with the Justice Department. He was also “not supposed to be involved” with the FBI. That meant he could not be sure the government was “going after” Hillary Clinton. “I’m not supposed to be doing the kinds of things I would love to be doing,” he lamented, “and I am very frustrated by it.”

Now that he has been re-elected, Mr Trump has chosen to do the things he loves, and he has set aside conventions that insulated the Department of Justice from White House pressure. He is paying a price for erasing any expectation the department would operate independently, as it did under Joe Biden in prosecuting prominent Democrats, including his son, Hunter. Mr Trump’s bandying of conspiracy theories about Jeffrey Epstein helps account for the anger of his MAGA base at the nothing-to-see-here position of his top Justice officials about records of the investigation into Epstein. But because he has left no doubt who is in charge, that anger is directed at him, too. “Why is Trump blowing up his base to protect child predators?” wondered Ann Coulter, a fierce advocate of the president, in a column in mid-July.

It could have been worse for Mr Trump: he could have had his first choice for attorney-general, Matt Gaetz, then a congressman from Florida. He withdrew just before the House Ethics Committee said it found “substantial evidence” he had committed statutory rape, an accusation he denied. Unlike Mr Gaetz, Mr Trump’s second choice, Pam Bondi, has deep experience prosecuting crime, including child abuse. She spent 18 years as a prosecutor in Florida, then won two terms as state attorney-general. A lawyer for Mr Trump in his first impeachment, she claimed after the 2020 election that he had won Pennsylvania, which he lost. But before being confirmed as attorney-general she assured senators that politics would play no part in her decisions. The explosion over the so-called Epstein files shows even Mr Trump’s ardent supporters are not comforted by her credentials or assurances.

Like other top Trump appointees, Ms Bondi pairs awe for Mr Trump—“the greatest president in the history of our country”, she has called him—with conviction about the vast powers of his office. In her first day on the job she issued a memo to her department demanding “zealous advocacy” to defend “the interests of the United States”. Those interests, she continued, “are set by the nation’s chief executive” and no attorney could presume to substitute their own judgment. The same day she created a “Weaponisation Working Group” to investigate a special counsel who investigated Mr Trump, and the officials who investigated those who attacked the Capitol on January 6th 2021. Ms Bondi has presided over the departures of many career prosecutors and shifted authority to Washington from US attorneys’ offices. Probably her most sweeping articulation of presidential power came in defence of the president’s decision to defy a law banning TikTok. Abruptly shutting it down, she wrote, would “interfere with the president’s execution of his constitutional duties” regarding national security and foreign affairs. That standard would seem to empower a president to ignore any law touching such matters.

The endless personal drama of Mr Trump and the law—his perils and escapes, his pardons of allies, his accusations of crimes by adversaries—can make it easy to overlook that, in bringing the Justice Department under his thumb, he is not just heeding his own druthers. He is also fulfilling a long-cherished conservative theory about how the constitutional system is supposed to work. Under this theory changes after the Watergate scandal threw the balance of powers out of whack. Congress overreached in passing laws to constrain the president in matters from waging war to managing the budget, while new norms excessively shielded investigators and prosecutors from presidential oversight.

The constitution charges the president with ensuring the law is faithfully executed, and the extent of that authority has never been delineated by Congress or the courts. Mr Trump may not have been wrong when he said, in his first term, “I have an absolute right to do what I want to do with the Justice Department.” Those who embrace such ideas argue that, unlike civil servants, the president can be held politically accountable for his choices. But this confidence seems misplaced when the president is a lame duck, in an era when polarisation has rendered impeachment futile. Further, having the right to such authority does not mean presidents are wise to exercise it, which Mr Trump appears now to grasp, given his recent forays into implausible deniability. “I have nothing to do with it,” he insisted, when asked if he would appoint a special counsel to investigate the Epstein matter—though the White House then said he opposed the idea.

Witless for the prosecution

The erosion of prosecutorial independence does not in itself mean that politics is undermining justice. It certainly does not establish that Ms Bondi made an unprincipled decision in concluding, as an unsigned statement put it, that “no further disclosure” of the Epstein files was “appropriate or warranted”. The opposite could be true: that on studying the evidence, she bravely concluded, not just that she had been wrong to promise “truckloads” of new information, but that Mr Trump had been wrong to commit to releasing the files, and wrong in spreading rumours about Epstein. In any case, another test of Ms Bondi’s integrity, and of Mr Trump’s supporters’ faith in him, lies ahead: endorsing accusations by Tulsi Gabbard, the director of National Intelligence, Mr Trump on July 22nd said Barack Obama committed treason in the investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election. “Whether it’s right or wrong, it’s time to go after people,” he said. ■

The Americas | Dear Donald, thanks! Yours, Lula

Trump’s astonishing battering of Brazil

MAGA bullying is backfiring, boosting Lula’s government

Illustration: Ricardo Santos

Jul 24th 2025|São Paulo|5 min read

Listen to this story

Rarely since the end of the cold war has the United States interfered so deeply with a Latin American country. On July 9th Donald Trump pledged tariffs of 50% on Brazilian exports, citing a “witch hunt” against Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right former president, who is soon due to stand trial for allegedly plotting a coup, a charge he denies. On July 15th Jamieson Greer, the United States trade representative, started investigating Brazil’s trade practices. On July 18th the US State Department revoked the visas of most Brazilian Supreme Court judges and other officials connected to Mr Bolsonaro’s prosecution. Marco Rubio, the secretary of state, has said he wants to use the Global Magnitsky Act to place sanctions on Alexandre de Moraes, a prominent justice, an action usually reserved for dictators and warlords.

Mr Trump and Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, are ideological foes and Mr Trump’s allies have long decried a probe Mr Moraes leads into online disinformation. Yet the trigger for Mr Trump’s attack appears to have been the summit of the BRICS, a group of emerging-market countries, that Brazil hosted on July 6th and 7th. Lula, as the president is known, has called the threats “unacceptable blackmail” and an attack on Brazil’s sovereignty. He also threatened to start taxing American technology companies. Brazil’s Congress, which is controlled by right-wing parties, has rallied around Lula and is mulling retaliatory tariffs.

But Lula saved his venom for Mr Bolsonaro and his son, Eduardo, a congressman, who took leave from his job in March and moved to Texas, where he has been lobbying Republican congressmen to put sanctions on Mr Moraes. Lula has called them “traitors”. “Let them be ashamed, hide in their cowardice, and let this country live in peace!” he told a rally on July 17th. Instead of rebutting the charge, Eduardo boasts about his access to the White House. After Mr Moraes’s visa was revoked, he posted on X: “I can’t see my father, and now there are Brazilian officials who won’t be able to see their families in the US either!”

Brazil’s powerful Supreme Court has responded aggressively, too. On July 18th Mr Moraes ordered Mr Bolsonaro to wear an electronic ankle monitor, confined him to house arrest during nights and weekends, and barred him from speaking to foreign officials or giving interviews. On July 19th Mr Moraes froze Eduardo’s assets as part of an investigation into whether his lobbying efforts are an attempt to obstruct the case against his father.

If drawing Mr Trump’s ire was supposed to bolster Brazil’s right ahead of a general election next year, the plan is backfiring. Brazilians of all stripes are backing Lula. Effigies of Mr Trump have been burned on the streets. Lula’s approval rating, which had been flagging, has perked up. He now leads the field of potential candidates for next year’s race.

Mr Trump’s tariffs have also given Lula an “incredible get-out-of-jail-free card”, says Andre Pagliarini of the Washington Brazil Office, a think-tank. “Whatever economic pain Brazil is likely to feel between now and the election, the government can credibly point to the Trump tariffs as the cause, whether it’s true or not.”

In fact, the tariffs may cause pain for Mr Bolsonaro and his right-wing allies. Only 13% of Brazil’s exports go to the United States, worth $43bn a year (some 28% go to China, a share likely to grow if Mr Trump’s tariffs are enacted). Goldman Sachs, a bank, reckons tariffs may lower growth by 0.4 of a percentage point to around 2% this year. Yet the impact is likely to fall disproportionately on companies based in regions that are Bolsonaro strongholds. More than a third of unroasted coffee beans imported into the United States come from Brazil. The vast majority of imported orange juice comes from Brazil, too. Beef imports are growing fast. Economists at the Federal University of Minas Gerais reckon that some 110,000 Brazilians will lose their jobs if the tariffs come into effect, mostly in agriculture. It is telling that Brazil’s national confederation of farmers, usually a Bolsonaro stalwart, condemned the “political nature” of Mr Trump’s tariffs. Even Mr Bolsonaro has tried to distance himself. He says the tariffs have “nothing to do with us”.

Brazilians are particularly riled by the idea that the Trump administration may go after Pix, the popular instant-payments system launched by the central bank in 2020. This was not threatened explicitly, but Mr Greer included “electronic payment services” on a list of Brazilian practices his office deems “unreasonable or discriminatory” to American firms. “The idea that Pix represents an unfair trade practice against the US is unfounded,” says Ralf Germer of PagBrasil, a leading Brazilian payments processor. Pix has spurred competition in Brazil’s previously fusty banking sector by offering low-cost infrastructure whereby upstart firms can easily provide financial services. That increased competition has also undercut American payment firms like Visa and Mastercard.

Complaints about unfair trade practices have merit. Brazil is one of the world’s most closed economies, with 86% of imports facing non-tariff barriers (as do 77% of imports to the United States and 72% of imports globally). Domestic industry receives endless bungs from the federal and local government. But if this is Mr Trump’s real concern, he has not said so. Brazil’s government has been attempting to contact the White House since May in order to negotiate a trade deal, but their entreaties have been ignored.

Only Eduardo Bolsonaro, it seems, has Mr Trump’s ear. “Trump is someone I admire, someone I look up to, someone I want to get to know better so that, who knows, maybe in the future, if I have power, I can follow in his footsteps in Brazil,” he says, speaking by video call from his office in Texas, which is adorned with MAGA hats and crucifixes.

Lula appears reinvigorated by the feud. He now wears a blue cap that says “Brazil belongs to Brazilians.” But a former Brazilian diplomat says Lula’s officials worry that the boost may not last. If tariffs come into force and economic pain sets in, Lula will struggle to lay all of the blame with Mr Bolsonaro. The question is which 79-year-old will back down first: the impetuous Mr Trump or the strong-willed Lula. ■

Middle East & Africa | A deepening catastrophe

As Gaza starves, Israel fights on

Its generals think the war against Hamas has become pointless, but a ceasefire remains elusive

Photograph: Reuters

Jul 24th 2025|Jerusalem|4 min read

Listen to this story

IN A LONG-TERM planning session on July 21st Lieutenant-General Eyal Zamir, the head of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), told his fellow generals that 2026 would be a year of “preparedness, realising achievements, returning to competency and fundamentals”. In the meeting, the largest since the war in Gaza began nearly 22 months ago, he said the army should be preparing for another war with Iran. General Zamir’s message was not intended just for the officers in the room. He was telling the government and the Israeli public that the IDF’s top brass did not think the Gaza war should continue.

And yet it continues. The night before the generals’ meeting, the IDF began a new offensive aimed at encircling Deir al-Balah, a town on the coast of the strip that had previously remained relatively unscathed (see map). That illustrates a growing difference between the IDF and the government of Binyamin Netanyahu, the prime minister. The generals think that, militarily, there is no point continuing the war against Hamas, the Islamist group that still controls parts of Gaza. The government wants them to fight on.

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

For Gazans, that means a catastrophic situation is getting worse by the day. Deir al-Balah houses the offices of many aid organisations. Many refugees have taken shelter there. Since the IDF began its offensive on July 20th, dozens of people have been killed in Israeli air strikes on the town. On July 21st the IDF struck the staff quarters and the main warehouse of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and detained one WHO employee. The organisation said the destruction of the warehouse, which was subsequently looted, had crippled its efforts to sustain Gaza’s collapsing health-care system.

At the same time, Israel continues to wage what it calls an “economic war”. The point is to replace the existing humanitarian supply networks of international organisations, which it claims were being controlled by Hamas, with its own system. The bulk of the aid that still gets into the strip is distributed at four hubs operated by the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) in areas controlled by the IDF (see map). Food distribution at the hubs, which are run by American contractors, is chaotic and often deadly. In recent days, dozens of Gazans have been crushed to death while queueing at the centres; since the hubs opened in May hundreds more have been killed by IDF fire on the approach routes.

Map: The Economist

Some aid groups are still allowed to bring limited supplies into Gaza City. Gangs that Israel says are fighting Hamas are also allowed to bring in their own food. Yet there is not enough aid to keep Gazans from starving. On July 21st countries including Britain and many member states of the European Union condemned the “drip feeding” of aid and called on Israel to abide by its obligations under international humanitarian law. On July 23rd a group of more than 100 international organisations said Israel’s distribution system was creating “chaos, starvation and death”. Supplies had been “totally depleted”, they said, with their own colleagues wasting away before their eyes. The same day health authorities in Gaza reported that 46 people had starved to death in July, ten of them over the previous 24 hours.

Israel denies that it is responsible for hunger in Gaza. It called the countries’ statement “disconnected from reality” and blamed Hamas for undermining aid distribution and failing to agree to a ceasefire.

The latest indirect talks in Qatar between Israeli and Hamas negotiators about a ceasefire have yet to yield a breakthrough after nearly three weeks of negotiations. The basic framework envisages a 60-day truce. During that time, Hamas would release some of the Israeli hostages it has held since October 2023 in exchange for Palestinian prisoners and further talks towards a full ceasefire would be held.

But the extent of the IDF’s withdrawal from Gaza continues to hold up a deal. Hamas wants Israel to withdraw as a prelude to a full retreat from Gaza. Mr Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition partners want perpetual Israeli occupation of Gaza and the removal of its people, most of whom have already been crammed into a small area in the centre of the strip. Agreeing on a ceasefire would probably push Mr Netanyahu’s partners to bring down his government. Yet without a ceasefire, it will be hard to avert full-blown famine in Gaza. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Cigarettes, booze and petrol bankroll Europe’s welfare empire

But what if people give up their sinful ways?

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Jul 24th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Is it possible to feel the burden of sin in a continent that is all but godless, as Europe is these days? Prostitution barely generates a frisson in Belgium, a land of unionised hookers. Puffing cannabis is legal in Germany, of all places. Gambling via lotteries or mobile apps is uncontentious just about everywhere. But to feel the weight of social disapproval, try buying a bottle of wine in Sweden. Since 1955 a state-run monopoly has begrudgingly dispensed alcohol to those who insist on drinking it. The Systembolaget, as it is known, oozes disapproval. Stores are sparse and closed on Sundays. If you find one, forget posters of appealing vineyards as you browse the shelves: the decor is part Albanian government office, part pharmacy. There are no discounts to be had, nor a loyalty programme. Wine is left unchilled lest a customer be tempted to down it on a whim. As they queue to pay, shoppers are made to trudge past a “regret basket” that primly suggests they leave some of their hoard behind. The road to Swedish hell is, apparently, lined with lukewarm bottles of sauvignon blanc.

And pricey ones, too. For it is not only Systembolaget’s profits that flow to the state, but the hefty excise duties imposed on what it sells. Whether in restaurants or in shops, booze is eye-wateringly expensive: in Sweden drinking serves both to numb the senses and lighten the wallet. Across Europe such “behavioural taxes” have become mainstream, and a useful fiscal bump to sustain stretched welfare states. Smokers have long put up with inflation rates on cigarettes reminiscent of Weimar Germany. A dozen European countries including France and Poland impose tithes on sugary drinks. Energy taxes clobber motorists whose cars are fuelled by planet-warming petrol. Such “sin taxes” allow European politicians to indulge in their two great passions: nannying the public and filling public coffers. Alas the two are in opposition, seeing that pricey sinning makes for fewer sinners.

Europe has a special (and arguably dubious) rationale for taxing the unholy trinity that are booze, cigs and petrol: its publicly funded health-care systems ultimately pick up the tab for citizens’ bad habits, and society at large will pay the cost of adapting to global warming. Reducing such “externalities” through tax has a long pedigree, going back to 17th-century British levies on tobacco. Over time the taxes have become not so much a nudge as a walloping. Irish smokers pay €18 ($21) for a pack of cigarettes these days, of which 80% flows straight to the state. A bottle of Absolut vodka in Sweden includes €14 of excise, well over half its price in the Systembolaget. The Netherlands adds €0.79 to each litre of petrol, equivalent to $3.55 a gallon, more than Americans pay at the pump. Alcohol and cigarettes contribute over €100bn a year to Europe’s exchequers, with energy taxes over double that—a handy few percentage points of GDP. To some governments they are vital: in Bulgaria environmental and excise taxes amount to around a tenth of the total state budget.

The downside of sin taxes is that government finances suffer when bad habits get kicked. Smoking and drinking have both declined markedly in recent decades. Whether that is because of high taxes or other factors is up for debate. Young Europeans are on a straighter path than their parents were, including when it comes to untaxed activities like sex and illegal drugs. But the result is that revenues from smoking and drinking are down by around a fifth as a share of GDP in the past decade or so. Green taxes will cause an even bigger hole in public finances. By 2035 no new cars with combustion engines will be sold in the European Union; by 2050 the bloc is pledging to cut carbon emissions to net zero. Finance ministers will balk. Though the gains made from falling sales of accessories to sin will be felt years in the future, the fiscal pain of shrinking revenue hits immediately.

Taxing sin has other issues. It often disproportionately burdens the poor, who smoke, drink and gamble more as a share of their income and drive older petrol-guzzling cars. Levies applied by one national government are easy to circumvent, especially in the EU where people can freely travel to neighbouring countries with lower excise rates to stock up on Marlboros, cognac and diesel. No tax is popular, but those on petrol have a special way of irking people. In 2018 a rise in fuel duties sparked the “yellow jackets” protests in France. And what of the argument that unhealthy habits like smoking are good for the exchequer? In 2001 the Czech arm of Philip Morris, a cigarette peddler, even argued that smokers save the state money by dying younger, thus relieving the public purse of the need to pay the pensions, health care and housing of those killed off early.

Confessions of a tax collector

As revenues on existing sin taxes decline, finance ministers are on the hunt for new ones to replace them. After sugary drinks, it may soon be the turn of meat to get a special tax: methane-belching cows are the next frontier in combating climate change. The EU is brimming with ideas of new sins to tax, not least as it hopes some might fund its budget directly. Levies on unrecycled plastics already flow to its coffers. On July 16th the European Commission proposed to extend excise on tobacco beyond cigarettes to vapes, as well as receiving some of the proceeds of carbon credits.

Why stop there? Smoking, drinking and boiling the planet are bad, certainly. But policymakers might usefully update the list of sins to be tackled. Would any sane European oppose tripling the income taxes of people who blithely watch videos on public transport without earphones? Charlemagne would happily vote for tourism levies targeting social-media influencers who turn perfectly good Parisian cafés into Instagram backdrops. Electric scooters are a nuisance, too. The problem with taxes on addiction is it is easy for politicians to end up addicted to them. ■

International | The Telegram

The surprising lessons of a secret cold-war nuclear programme

America is sick of policing the world. More nuclear-armed states will not help

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Jul 22nd 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

IN THE DEPTHS of the cold war, American spooks and generals came to suspect that the nuclear-weapons club was about to gain an incongruous new member. That state was Sweden, a neutral power that sat out both world wars, then declined to join the West’s new defence alliance, NATO, at its founding in 1949.

For all Sweden’s war-shunning ways, by the early 1960s its scientists were perhaps two years from building a nuclear bomb, after years of secret work. Officials held James Bond-ish discussions about hiding a plutonium-production plant in a vast rock cavern. Military commanders drew up plans to maul any threatening Soviet force with an arsenal of 100 tactical, or battlefield-scale nuclear bombs, missiles and torpedoes. A favoured scenario involved targeting a Soviet invasion fleet as ships clustered in a port embarking troops before crossing the Baltic Sea.

It was cold-war America’s policy to prevent the nuclear-weapons club from growing. What looks like a trap was duly set. This was baited with uranium-235, enriched for use in civilian power generation and offered to Sweden (and others) at low cost. With cheap fuel available, why would Sweden build its own reprocessing plant, a US atomic-energy chief asked a Swedish scientist in 1963. Was it planning to build weapons, the American went on. If so, his government would take an extremely negative view.

As America applied the screws, domestic politicians were also turning against the programme. After lengthy wrangling, Social Democrat leaders decided that a small nuclear arsenal of the sort envisaged would not deter the Soviets but rather make them target Sweden, while straining defence budgets and harming the country’s moral standing. By the mid-1960s the programme was over.

Sweden’s atomic adventure has lessons for the present day. During the cold war, a fearful time, several industrialised countries considered going nuclear. America worked hard to thwart such proliferation, using threats but also economic incentives and security guarantees. The world is alarming once more. Debates about acquiring nuclear weapons are growing louder in countries with scary neighbours, from South Korea and Japan, in North Korea’s and China’s backyard, to Poland, on Russia’s doorstep.

President Donald Trump has, over the years, swerved between expressions of horror about nuclear war and insouciance about countries getting their own bombs. During his presidential campaign in 2016, Mr Trump averred that it might be “better” for Japan to go nuclear, to deter North Korea’s nuclear-armed regime. Mr Trump added that America “cannot be the policeman of the world. And unfortunately, we have a nuclear world now.” More recently, Mr Trump has railed against the cost of keeping troops in Japan and South Korea, and demanded that Europe spend far more on its own defence.

Months before the elections in 2024, Elbridge Colby, who now serves as Mr Trump’s undersecretary for defence policy, told South Korean reporters that their country should take “primary, essentially overwhelming, responsibility for its own self-defence against North Korea because we don’t have a military that can fight North Korea and then be ready to fight China.” Mr Colby added that America should refrain from imposing sanctions on a nuclear-armed South Korea.

For its part, Russia does not hide its admiration for the clout conferred by nuclear arms. President Vladimir Putin has made nuclear threats to Western governments that dare to help Ukraine (stoking alarm that saw Sweden join NATO in 2024). Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, recently hailed North Korea’s “timely” decision to pursue nuclear weapons as the reason that nobody is “even contemplating the use of force” against that country.

Actually, there is no reason to imagine that an enlarged nuclear club would make the world more stable, or let America off the hook for the security of its friends. Sweden is a prime example of a country whose small arsenal was never intended to defeat its larger adversary. Its goals were two-fold: to raise the costs of a Soviet invasion; and to make American assistance more likely.

America Firsters need to read more history

Mats Bergquist, a former Swedish ambassador and historian of his country’s cold-war foreign policy, describes a twin-track strategy. Plan A was neutrality. Discreet military co-operation with the West was Plan B. Posted to Washington in the 1970s, he observed the close ties between the two countries’ armed forces, even after leading politicians wrangled publicly over the Vietnam war and other divisive topics. After the late 1950s Swedish defence planners talked of fighting “until help can be obtained”. That reflected the government’s “fairly strong conviction” that America’s security umbrella would extend to Sweden in a crisis, says Mr Bergquist.

To be precise, Sweden was pursuing what Vipin Narang, a scholar of deterrence, calls a “catalytic nuclear posture”, in other words one designed to trigger help from a superpower patron. This is a common strategy for smaller nuclear powers, says Scott Sagan of Stanford University. He points to the Yom Kippur war in 1973, when Israel signalled to America that it might use nuclear weapons, triggering a hasty American airlift of conventional arms.

For deterrence scholars, a nuclear South Korea raises a whole other set of worries. Special risks are created when two rivals fear surprise attack from the other. Today, nuclear-armed North Korea and conventionally armed South Korea fit that pattern. Both have already adopted pre-emptive, hair-trigger strategies. All new nuclear powers follow “a learning curve”, for instance as they distinguish false alarms from real threats, worries Professor Sagan.

South Korea would be a nuclear newcomer on a hair-trigger, with a volatile neighbour. If they were veering towards a nuclear war, even an America First president could be dragged in. ■

Business | Schumpeter

The dark horse of AI labs

How Anthropic’s missionary zeal is fuelling its commercial success

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jul 23rd 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Perhaps it is inevitable that Anthropic, an artificial-intelligence (AI) lab founded by do-gooders, attracts snark in Silicon Valley. The company, which puts its safety mission above making money, has an in-house philosopher and a chatbot with the Gallic-sounding name of Claude. Even so, the profile of some of those who have recently attacked Anthropic is striking.

One is Jensen Huang, boss of Nvidia, the most valuable company on Earth. After Dario Amodei, Anthropic’s chief executive, raised the spectre of big job losses as a result of advances in AI, Mr Huang bluntly retorted: “I pretty much disagree with almost everything he says.” Another is David Sacks, a venture capitalist (VC) who is one of President Donald Trump’s closest tech advisers. In a recent podcast, he and his co-hosts accused Anthropic of being part of a “doomer industrial complex”.

Mr Amodei gives short shrift to such criticisms. In an interview on the eve of the release of Mr Trump’s AI Action Plan, he laments that the political winds have shifted against safety. Yet even as he cuts a lonely figure in Washington, Anthropic is quietly becoming a powerhouse in business-to-business (B2B) AI. Mr Amodei can barely suppress his excitement. After his firm’s annualised recurring revenue grew roughly tenfold over the course of last year, to $1bn, it is now “substantially beyond” $4bn, putting Anthropic possibly “on pace for another 10x” growth in 2025. He doesn’t want to be held to that prediction, but he is over the moon: “I don’t think there’s a precedent for this in the history of capitalism.”

Schadenfreude helps, too. Mr Amodei and his co-founders, including his sister Daniela, set up Anthropic after abandoning OpenAI in 2021 over safety concerns. Their rival went on to make history by launching ChatGPT. OpenAI’s revenue, which hit a $10bn annualised run rate in June, far eclipses that of Mr Amodei’s lab. So does its latest valuation, of about $300bn, almost five times that of Anthropic. Yet even as ChatGPT’s popularity continues to soar, Anthropic has muscled in on OpenAI’s enterprise business. B2B accounts for 80% of Anthropic’s revenue, and its data suggest it is now in the lead when it comes to providing companies access to models via plug-ins known as APIs. Its latest model, Claude 4, is a hit among fast-growing coding startups, such as Cursor, as well as software developers in more established firms. Programmers, Anthropic believes, are early adopters of technology, and it hopes they will open doors to the rest of their companies.

Among some of Anthropic’s founders, there is a pinch-me quality to this commercial success. Many are science nerds, not wannabe plutocrats. Their expertise is in scaling laws—the more computational power you throw at a model the better it gets—and safety, not sales. When they gather for dinner they discuss how “weird” the company’s growth is. Anthropic continues safety-testing products when competitors are about to ship theirs. Claude Code, a fast-growing programming bot built for internal use, was commercialised only as an afterthought.

Yet while safety is central to Anthropic’s mission, it turns out it sells well, too. Early on Anthropic decided that its ethical concerns precluded it from building entertainment or leisure products, which were potentially addictive. Instead it focused on work, where most people spend the majority of their time anyway. This, Mr Amodei says, has become “synergistic” with the safety mission. Like Anthropic, businesses want trustworthy and reliable AI. They respect its interest in interpreting models to understand why things go wrong. At the same time, Anthropic’s focus on scaling has kept it competitive. Companies need access to the best models. Claude 4, which operates autonomously for long periods and is able to use other computer programs, allows companies to outsource well-paid work.

The huge cost of training Anthropic’s models is the problem. Like its peers, it is burning through cash. That requires regular fundraising. Once again Anthropic appears to be preparing to go cap in hand to investors. Press reports speculate that Amazon is considering upping its stake, and that some VCs are willing to provide money at a $100bn valuation, up from $61.5bn in March.

Yet the dash for cash highlights glaring paradoxes, as Anthropic’s material needs clash with its missionary zeal. On July 21st Wired, a tech publication, leaked an agonised Slack message from Mr Amodei in which he explained to co-workers why he had reluctantly decided to seek money from Gulf states. “‘No bad person should ever profit from our success’ is a pretty difficult principle to run a business on,” he wrote. He tells The Economist that he continues to have security concerns about American companies building data centres in the Gulf. But as for investment from the region, his scruples have eased. “Those are big sources of capital.”

Anthropic’s safety mission may, at times, prove awkward, but it breeds a race to the top, argues Mr Amodei, as other companies feel compelled to follow Anthropic’s example. His convictions appear to be deeply held. He believes AI holds enormous economic potential, as well as the power to cure “diseases that have been intractable for millennia”, but argues that it is vital to also consider how societal costs, including job losses, will be managed. He contends that the power AI bestows will be safer in the hands of a democracy like America’s than an autocracy like China’s. That Mr Trump has relaxed exports of AI chips to China, in response to lobbying by Nvidia’s Mr Huang, is “an enormous geopolitical mistake” in the eyes of Mr Amodei.

The enshittification of AI

Advocating his cause is hard work. But Ravi Mhatre of Lightspeed Venture Partners, a big Anthropic backer, says that when models one day go off the rails, the AI lab’s safety focus will pay dividends. “We just haven’t had the ‘oh shit’ moment yet,” he says. ■

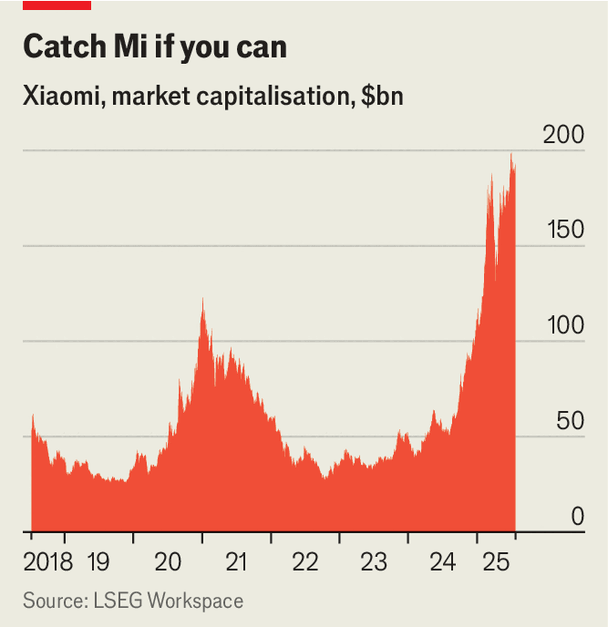

Business | Xiaomi the money

China’s smartphone champion has triumphed where Apple failed

Having conquered carmaking, Xiaomi now has its sights set on world domination

Illustration: Mariaelena Caputi

Jul 21st 2025|Shanghai|6 min read

Listen to this story

Ever since he co-founded Xiaomi in 2010, Lei Jun, the chief executive of the Chinese tech giant, has pulled off feat after feat of salesmanship. A decade ago he earned a Guinness World Record for selling 2.1m smartphones online in 24 hours. These days, though, he is not just flogging cheap phones. Last month Xiaomi sold more than 200,000 of its first electric SUV, the YU7, within three minutes of bringing it onto the market.

Xiaomi’s rise over the past few years has been vertiginous. Only Apple and Samsung sell more smartphones worldwide. The company also peddles a vast array of devices that connect to its handsets, from air-conditioners and robo-vacuums to scooters and televisions. After a slump in 2022, which it attributed to “cut-throat competition” in China for consumer electronics, Xiaomi has roared back to growth: its revenue increased by 35% last year. Since the beginning of 2024 its market value has nearly quadrupled, to HK$1.5trn ($190bn; see chart).

Chart: The Economist

With the successful release of the YU7—its second electric vehicle (EV) after the SU7, a sporty sedan launched in March last year—Xiaomi has pulled off a feat that eluded Apple, which ditched plans to make its own EV after burning billions of dollars on the effort over a decade. Xiaomi, which announced its carmaking ambitions in 2021, has put more than 300,000 of its EVs on Chinese roads over the past 15 months, and has a backlog of orders that will take more than a year to fill. Although its EV division has lost money so far, Mr Lei has said he thinks it will become profitable later this year, an impressive feat in China’s brutally competitive car market.

Xiaomi now has its sights set on world domination. Over the coming years it intends to open 10,000 shops abroad, up from just a few hundred last year, which it will use to show off its sleek new cars alongside its consumer electronics. Can anything stop its stunning ascent?

Xiaomi’s success in EVs is partly down to being in the right place at the right time. China these days is awash in carmaking know-how; Mr Lei was able to nab top talent from a number of other companies. Prices for parts and machinery have plummeted, given the oversupply of both. Getting a factory approved and built can be done far more quickly in China than most other places.

But Mr Lei also deserves plenty of credit. Insiders note that, unlike Apple’s Tim Cook, he took personal control over his company’s carmaking project. Success required deep changes to how the company operated. Prior to its foray into EVs, Xiaomi did not own factories; like Apple, it outsourced the production of its phones and other devices. Yet it chose to build its own EV factory in Beijing, which it is expanding, in order to ensure strict oversight. It is now adopting the approach elsewhere in its business: last year it began producing smartphones at another facility in Beijing, and it is building a plant in Wuhan where it will make other connected devices, starting with air-conditioners.

Xiaomi’s marketing strategy, which relies heavily on Mr Lei’s cult following in China, has also aided its expansion into EVs, much as adoration for Steve Jobs helped Apple sell its first iPhones. Wuhan University is said to have enjoyed a surge in interest thanks to Mr Lei’s attendance there some 30 years ago. “Mi Fans”, as diehard Xiaomi customers are known, collect company memorabilia and race to get their hands on every new product. Xiaomi has even managed to sustain the excitement around its EVs despite a horrific accident in March in which three university students were killed in an SU7 that was being piloted down a motorway by the company’s autonomous-driving system. The episode led to criticism of Xiaomi’s safety standards and a temporary sell-off in the company’s shares, but did not quell demand for the YU7 when it was launched three months later.

It helps, too, that Xiaomi has a vast customer base to which it can hawk new products. At the end of last year it claimed 700m monthly users across its devices globally, up by about 10% from the year before. Many of them play games purchased on Xiaomi’s app store and view ads sold by the company (these generate half of the company’s total profit, according to Bernstein, a broker). And a sizeable share of users buy their Xiaomi products directly on its app.

The company has already proved adept at persuading them to upgrade to more expensive phones. It needs only a small fraction of them to buy a car for the endeavour to be a huge success. Many of Xiaomi’s Chinese customers were in their early 20s when they bought one of its first smartphones a little over a decade ago. They are now in their mid-30s, the target demographic for Xiaomi’s EVs.

Mr Lei is looking beyond China, too. Nearly half of the revenue the company makes from smartphones and other connected devices comes from overseas, primarily in developing markets such as India and Indonesia. Mr Lei wants Xiaomi to start selling its EVs abroad by 2027. These will probably not enjoy the kind of rapturous reception they have received at home: Xiaomi does not command anything close to the same brand loyalty in foreign markets, and few overseas customers will have heard of Mr Lei. That helps explain why Xiaomi is investing in building a vast network of bricks-and-mortar shops abroad, which should raise its profile.

At the same time, the company plans to continue expanding into new lines of business. It has developed its own humanoid robot, CyberOne, and in May unveiled an advanced three-nanometre chip it had designed itself. Roughly half of its staff work in research and development, spending on which grew by 26% last year, to $3.4bn—more than the company generated in net profit. The thinking within the firm is that by developing technologies from the ground up, it can identify efficiencies and raise barriers to competition.

Perhaps the biggest risk for Xiaomi is that, given its many products and markets, it is fighting on too many fronts. The price war among Chinese EV companies continues to intensify, and despite its growth, Xiaomi remains a small player. It sells around 20,000 cars a month, less than a tenth of the figure for BYD, the market leader. Competition in smartphones is also heating up as Huawei, another Chinese tech giant whose handset business was hobbled by American sanctions in 2019, makes a comeback. Still, Mr Lei’s salesmanship is not to be underestimated. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Why 24/7 trading is a bad idea

There are advantages to the old-fashioned working day

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Jul 23rd 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

Stock exchanges are the quaintest corners of modern finance. At other financial institutions, the typical trading floor features people in t-shirts sitting at ergonomic keyboards, sipping herbal tea and reviewing computer code. Enter New York’s bourse, meanwhile, and you might as well have been through a time warp. Tense-looking people bustle everywhere sporting headsets and relics known as neckties. Everyone looks as if they shout a lot. As in a cattle market, opening and closing bells are rung to mark either end of the day’s trading session, at 9.30am and 4pm.

This last bit is the most anachronistic, and not because of the bells. Today’s markets, after all, have long ceased to respect the working day. Currencies, American Treasury bonds and crypto assets all trade around the clock.

Although investors the world over want to buy and sell American stocks, standard trading at both the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and its digital cousin, the Nasdaq, begins close to Hong Kongers’ bedtime and ends while Californians are having lunch. Pre- and post-market sessions facilitate some transactions from New York’s 4am and until 8pm. But few marketmakers operate during these, and liquidity can evaporate. Stock exchanges in Europe and Asia keep similar core hours to American ones, adjusted by time zone.

Now change is afoot. Both the NYSE and Nasdaq have applied for regulatory permission to extend their trading sessions, to 22 and 24 hours a day respectively. On July 20th the Financial Times reported that the London Stock Exchange is considering something similar. The transition is coming fast: Nasdaq expects to be open all night from the second half of 2026. So are investors, traders and financial plumbers ready for another market that never sleeps?

Some certainly are. Stock exchanges might not yet trade overnight, but plenty of alternative platforms do. In May 2023 Robinhood, a digital retail broker, began to allow all-night trading of 43 popular single stocks, before expanding this to many more. It joined Charles Schwab and Interactive Brokers, two rivals already facilitating some overnight trading; this year, on July 21st, Schwab said it would start offering the service for 1,100 securities. For decades institutional investors have had “dark pools”—venues for off-exchange stock trading, which can stay open all night. It is through these pools that the retail platforms often execute their clients’ overnight trades.

The problem with such trading is that price discovery can be fraught with difficulty. In fact, this is partly why institutional investors like dark pools: their lighter reporting requirements, compared with exchanges, allow big orders to be executed without alerting the wider market beforehand, which would move the price. Professionals taking the other side of these trades accept the risks and know how to navigate them. Amateurs, getting a worse price than they might have done in daylight, often do not.

Overnight exchanges would increase transparency, but might not improve the second drawback of the small hours: low liquidity. Even during the day trading is concentrated around the opening and closing auctions (held just before the respective bells), with much lower volumes at other times. The phenomenon is self-fulfilling, since high auction volumes allow for better price discovery, which means professionals often prefer to place their trades during them.

Regulators could compel marketmakers to offer quotes throughout the night, as they currently do throughout the day. However, thin liquidity decreases the proportion of buy and sell orders that can be netted off, forcing marketmakers to hold positions on their books for longer. The result is more risk, more capital that must be held against it and therefore higher trading costs. Even then, prices would remain more volatile than during the day.

And that is before considering the logistical nightmare that 24-hour exchanges would entail. The witching hours are currently when all manner of dull, but vital, post-trade processes take place, from settlement and valuation to the reconciliation of mistakes. Once trading is non-stop, there will be no pause for the financial pipes to clear—nor for traders to rest in the knowledge that the market is resting with them, so there is no need to refresh their screens. In today’s always-on world, stock exchanges’ limited opening hours might seem old-fashioned. But get ready to miss them once they’re gone. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

What economics can teach foreign-policy types

Hegemons should care about even puny countries

Illustration: Álvaro Bernis

Jul 24th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Markets work best when many companies vie for customers’ favour. They work badly when a few firms dominate, carving up sales between them. Economists therefore need a measure of whether markets are competitive or concentrated.

The most famous measure was invented by Albert Hirschman in 1945. It starts by summing the squares of each supplier’s market share. That makes it sensitive both to the number of suppliers and inequalities between them. A staple of antitrust investigations, his index, with minor modifications, crops up in courtrooms and classrooms. Almost every economics student comes across it.

Few will know that Hirschman invented the index to measure something else: the economic power wielded not by firms but by countries. It appeared in a book examining trade as a source of “political pressure and leverage”. Hitler’s Germany had exerted its influence over its neighbours in the 1930s not only through “diabolical cunning” but also the gravitational pull of its economy.

Hirschman rejected the naive belief that because trade is voluntary and mutually beneficial, it is geopolitically innocuous. Benefits can be mutual without being symmetrical. And if one country depends less on a relationship than its partner, it can extract concessions by threatening to walk away.

The German economist would not have been surprised by President Donald Trump’s tariffs or indeed China’s own attempts at economic coercion, which include export restrictions on vital inputs, such as rare earths. It is, therefore, a good time to revive the spirit of his inquiries, according to Christopher Clayton of Yale School of Management, Matteo Maggiori of Stanford University and Jesse Schreger of Columbia Business School. They are seeking to apply the modern toolkit of economics to geopolitics. The result is something they call “geoeconomics” (borrowing a term coined by Edward Luttwak, a historian and military strategist, in 1990). Whatever the subject is called, it is inescapable. Three years ago people asked the authors what geoeconomics was. Now they are asked not to go on about Mr Trump too much.

In their models, big economies—hegemons—can make demands of smaller ones by subjecting them to economic sticks and carrots. The losses a country suffers if it rejects such demands are a measure of the power the hegemon wields. Smaller countries can try to protect themselves in advance by decoupling and diversifying their economies. They might, however, overdo it, according to the authors’ models. Economic networks, be they banking systems, industrial ecosystems, or global trade itself, increase in value the more people take part in them. If one country withdraws to protect itself, it makes that network less attractive to others. That might shift their calculus in favour of decoupling, too.

To dissuade countries from insulating themselves, a hegemon might promise not to exploit its power too much. It might say, “Do business with me. I’m not going to bully you like crazy later. I’m only going to bully you a little bit,” as Mr Maggiori has put it. The hegemon might, for example, submit to international trade rules that put a ceiling on its tariffs. If the rules are credible, they can benefit the hegemon as well as everyone else. In these models, trade rules emerge not as the result of “globalist” planning, but as an act of enlightened self-interest on the part of a hegemon. The models make the nationalist case for multilateralism.

Their theory also aids measurement. In the spirit of Hirschman, they calculate their own indices of power, based on market shares and the ease with which imported inputs can be replaced. Their calculations bring out a vital implication of their theory: power does not grow in a straight line. It tends to shoot up as a hegemon’s market share nears 100%. There is an enormous difference between claiming most of a market and claiming almost all of it. The same is true of hard-to-replace inputs. There is a big difference between having few substitutes and none or nearly none.

This result makes intuitive sense. If a hostile America provides 80% of a country’s foreign financial services, the country’s other providers would have to expand their sales by 400% to replace it (an increase from 20 to 100 equals growth of 400%). If America instead provides 90%, the alternative providers would have to expand by 900%. An increase in market share of ten percentage points makes a 500 percentage-point difference.

All this has practical implications. America and its allies have a large share of the world’s financial services. Adding a country like Singapore to the coalition might not seem like much of a prize. But it would make a big difference; a small increase in a large market share yields disproportionate gains in power.

Bully for them

The same is true in reverse. Even small efforts to decouple from an abrasive hegemon can diminish its power by a surprising degree. America’s rivals are, for example, experimenting with alternatives to the dollar in international finance. These alternatives do not have to match the dollar in order to erode America’s financial clout. If they can capture even 10% of the market in small and medium-size countries, they can make a big difference, according to the authors. Going from 1% of the market to 10% can reduce American financial power as much as going from 10% to 50%, they argue. According to this logic, currencies like China’s yuan can defang the dollar even if they never dethrone it.

Hirschman’s book, in which he outlined his index, was largely forgotten by the economics profession until recently. Political scientists and other scholars now account for most of its citations, according to Messrs Clayton, Maggiori and Schreger. The three authors hope to revive interest in Hirschman’s work among their fellow economists. The inventor of the best known index of concentration warrants a broader, more diversified readership. ■

Science & technology | Well informed

Do probiotics work?

For a healthy microbiome, eating your greens is a surer bet

Illustration: Cristina Spanò

Jul 18th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

ADAZZLING menagerie of microbes live inside the human gut—by some counts a few thousand different species. Most residents of this gut microbiome are not the disease-causing kind. In fact, many do useful jobs, such as breaking down certain carbohydrates, fibres and proteins that the human body would otherwise struggle to digest. Some even produce essential compounds the body cannot make on its own, like B vitamins and short-chain fatty acids, which help regulate inflammation, influence the immune system and affect metabolism.

As awareness of the microbiome has grown, the shelves of health-food shops have become stocked with products designed to boost good bacteria. These usually fall into two categories: probiotics, capsules containing live (but freeze-dried) bacteria that, in theory, spring back to life once inside your gut; and prebiotics, pills made of fibres that beneficial bacteria feed on.

There may be good scientific reasons to tend one’s microbiome. Having a diverse array of gut bugs, with plenty of the good kind, seems to confer broad health benefits. A varied microbial population can fend off pathogens by competing with them for nutrients and space. Reduced diversity, by contrast, has been linked to obesity, type-2 diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Evidence for causal links is growing: randomised-controlled trials have shown that tweaking the microbiome can accelerate weight loss, reverse insulin resistance and improve IBS symptoms.

The microbiome’s influence may stretch well beyond the gut. Microbes seem to be important for mood: people with depression have less microbial variety in their guts than those without do, for example. One study from 2016, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, even found that transplanting the microbiome of a depressed person into a rat caused the animal to display behaviour characteristic of depression. An off-kilter microbiome has also been linked to respiratory infections: mice with fewer gut microbes are more likely to catch pneumonia or influenza.

For a diverse microbiome, diet matters. Microbes thrive on foods rich in fibre and digestion-resistant starch, so munching on fresh fruit, vegetables, legumes and nuts is a good place to start. Fermented foods and drinks, such as yogurt, sauerkraut and kombucha, also contain friendly micro-organisms like Lactobacillus. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics is important, as they wipe out good bacteria along with the bad.

Supplements seem equally appealing, but because they are not regulated as medicines, many have not been rigorously tested. “It is absolute cowboy territory in terms of marketing”, says Ted Dinan, a psychiatrist at University College Cork who studies the influence of the microbiome on mental health. Fortunately for consumers based in America, Britain and Canada, academics in those countries have developed apps (each called The Probiotic Guide) that can be used to search for probiotic products and check what scientific evidence, if any, backs them up. Nothing so comprehensive exists for prebiotics, as yet.

Taking the wrong product may not do much good, but it probably won’t do much harm either. “You really cannot overdose on probiotics,” says Glenn Gibson, a microbiologist at the University of Reading. Taking too many prebiotics, however, could temporarily disrupt the microbiome. The likely side-effect? “Gas,” he says. “But that’s more just antisocial than anything else.”■

Culture | Interior design

IKEA’s prints have transformed how homes everywhere look

Chances are you have come across a “Strix” cushion or a “Rinnig” tea towel

A collection of bright ideasPhotograph: © Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2025

Jul 23rd 2025|EDINBURGH|4 min read

Listen to this story

NO FIRM IN history has had as penetrating an impact on everyday design and taste as IKEA. Even if you have never found yourself winding through a shop, absent-mindedly adding “Billy” bookcases, “Rodalm” picture frames or “Glimma” tea lights to a trolley, you will probably have encountered “Stockholm” rugs, “Rinnig” tea towels or “Ektorp” sofas in the homes of friends or in Airbnbs. This is, after all, a company with over 480 shops in 63 countries, which generated around €45bn ($52bn) in sales last year.

IKEA has brought Swedish minimalism to the masses, usually in the form of white or beige mdf (medium-density fibreboard). It is synonymous with practicality and affordability—and spousal arguments over the instructions for assembling flat-pack furniture. Yet “Magical Patterns”, a new show at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh, shows off a bolder, brighter side to Ikea’s output by focusing on its textiles.

Fabrics were not a priority for the furniture firm when it was founded in 1943. Many of its soft furnishings came in unsexy shades of grey. But by the mid-1960s, a renaissance in textiles was under way in Europe and America. Fashionable women strutted about cities in shift dresses in geometric patterns. Mini skirts came in paisley and polka dots. Bell-bottom trousers were adorned with psychedelic prints.

ikea’s executives cottoned on to the market opportunity. A new generation of predominantly young female textile artists, including Bitten Hojmark, Inger Nilsson and Vivianne Sjolin, was brought in to create a distinct look that would appeal to the firm’s customers. The result was a playful explosion of colour, print and technical innovation that coincided with Ikea’s rapid expansion. By 1970 textiles accounted for about a quarter of the firm’s sales.

In all, the exhibition brings together 180 different fabrics on loan from the Ikea Museum at Almhult. (It is the first time this collection has gone on show outside Sweden.) Displayed together, the effect is a punch of graphic prints and bright shades—there are few minimal, monochromatic Scandinavian designs here.

Among Ikea’s offerings were the striped “Strix” and “Strax” fabrics, designed by Inez Svensson in 1971 in blue, orange, green, brown, yellow and white. Though they may appear simple, these were the product of engineering experimentation and marked the first time that horizontal stripes had been printed onto fabric. In the past stripes had to be woven in, making the fabric more expensive.

“Strix” and “Strax” kicked off what have since been characterised as the halcyon days of textile design. IKEA drew influential artisans into its operation; aficionados of Scandinavian design will encounter familiar names in the show, including Gota Tragardh, Sven Fristedt and 10-Gruppen (a design collective formed in 1970, of which Svensson was a part). ikea also collaborated with designers such as Marimekko, a popular Finnish textile company, and Zandra Rhodes, a British fashion designer who dressed stars including Freddie Mercury and Princess Diana. No matter who created the print, the emphasis was usually on maximalism and playfulness.

Photograph: © Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2025

As you might expect from a collection belonging to the brand’s own museum, “Magical Patterns” is particularly instructive in revealing how Ikea would like to be seen. As the title implies, this is an exhibition with an emphasis on the most beguiling and eye-catching prints of the past 60 years. In addition to red-on-pink polka dots, botanical subjects and chevrons, design motifs include multi-coloured buttons and broccoli florets waltzing over Pepto-pink stripes (“Anniken”, 2014). The “Randig Banan” print (also pictured), which combines bananas and stripes, was divisive at the time of its creation in 1985, but is popular today.

Ms Sjolin, who ran the textile department in the 1970s and 1980s, has spoken about how the firm used textiles as a marketing tool. Striking new designs were used to attract press attention, adorn catalogue covers and shop windows and get people talking. Though the daring designs may be the most memorable, the reality is rather more plain: it is the less vivid prints that have driven the multi-billion sales figures year after year.