The Economist Articles for Aug. 2nd week : Aug. 10th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.08.02조회수62 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Aug. 2nd week : Aug. 10th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Greenlash

The climate needs a politics of the possible

To win voters’ consent, policymakers must offer pragmatism and hope

Jul 31st 2025

Curbing climate change was never going to be easy. The fundamental energy balance of a planet cannot be changed overnight; nor can a fossil-fuel-based economy that serves billions of people be replaced without furious political objections. But today the problem looks particularly hard.

On July 29th, continuing President Donald Trump’s gutting of efforts to reduce emissions, America’s Environmental Protection Agency said it would renounce its main authority to regulate greenhouse gases. That goes along with his reckless attacks on climate science. In Europe the war in Ukraine has spurred growth in defence budgets, squeezing spending on green policies, which also face renewed political opposition. Some voters think the cost of cutting emissions is too high, or should fall on others. In poor countries, which have historically emitted far less than rich ones, many resent green policies they see as foreign and heedless of the desperate local need for energy. Sensing the political winds, big global firms have gone quiet about greenery, though many still pursue it.

None of this deprives the world of its technical ability to decarbonise a great deal of its economy; on that score things have never looked better. The cost of clean energy is tumbling, as the demand for it continues to grow.

The problem is politics. Many people do not believe that the strict “net zero” targets to which some governments have tied their climate policies are in their interest—or that they will bring benefits to anyone else. Some think they are being taken for chumps, paying good money to meet bad targets while businesses and people elsewhere are belching out carbon, chuckling as they do so. Seeing an ever-more-powerful China emitting more than Europe and America combined makes resentful Western voters seethe.

The scientific rationale for net zero is strong. An end to warming requires the level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to stop increasing. That means either a world with no such emissions or one which takes as much greenhouse gas out of the atmosphere as it puts in (the “net” in net zero). The logic is inescapable. The political rationale is clear, too. Saying you will hit net zero by a certain date is a definite goal, easily articulated. Hard, ambitious targets have advantages: you never know for sure what can be done until you try.

However, reaching net zero in the nearish future would require emission cuts to be quick, deep—and painful. For countries which have not yet seen any decline in emissions—which, worldwide, is most of them—the steepest cuts would have to come very early. In many cases such scenarios are barely physically imaginable, let alone politically feasible.

If a target is so hard that it cannot win consent, then it needs to be changed. But how? For rich countries to abandon stringent net-zero targets outright would demoralise greens, energise climate nihilists and make sensible reforms harder. Better to find ways to ease them into the “more of a guideline” category. There will be resistance from those who believe that all problems can be solved by “more political will”, but as a famously iron-willed German once said, politics is the art of the possible.

Better to be Bismarck

Some politicians get it. Mark Carney, Canada’s prime minister and an economist, understands that, in many situations, the most efficient way to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions is to tax them. But many voters hate such taxes, so he has been quick to rescind the aspects of Canada’s carbon-pricing scheme that affect them directly.

Instead of charging for pollution, many governments have subsidised its avoidance. Some subsidies have borne fruit. Extra demand has driven the virtuous cycle of larger volumes and lower prices that have seen wind, solar and batteries become more available and cheaper. Costs are now so low that unstimulated demand will drive them even lower. That more or less guarantees a growing amount of decarbonisation come what may. Even post-Big-Beautiful-Bill America will see its emissions shrink, albeit more slowly than they could have.

Nonetheless subsidies still distort markets and reduce emissions less cheaply than a carbon price normally would. So it makes sense to charge for emissions when it is politically feasible (for example, when it does not affect voters directly). Governments should also scrap the many subsidies that harm the climate, such as those still applied to fossil fuels.

They should try harder to reduce the pain inflicted when decarbonisation involves lots of ordinary people. Do not bully them into buying heat pumps when there are too few technicians to install them. Make switching to an electric car easier by building charging infrastructure and letting in cheap imports from China. Apply the same pain-reducing logic to adaptation. Marine Le Pen, the leading French populist, struck a chord when she complained that France’s elite had air conditioning but its masses did not.

America will play an unusual role so long as Mr Trump is in charge: as a cautionary tale. Some promising clean-energy technologies, such as advanced geothermal and possibly even fusion, now have bipartisan support. But Mr Trump’s war on climate action will leave the country worse off. At a time of rising energy demand, some of it needed to power artificial intelligence—a national-security priority—prices will rise. Efforts to establish an American renewables industry to rival China’s will wither.

Voters everywhere prefer cleanliness to pollution and a future in which they can thrive to one that looks dangerous. Those are more potent rallying cries than an abstract target. Stories that make people feel they are participating in progress still play well. The idea of not being subject to swings in fossil-fuel prices is attractive, too. “The art of the possible” may sound flat. But a politics of new possibilities could put climate policy on a more sustainable footing, as well as offering hope. That is what those fighting climate change need to offer.

Leaders | Block off the old chips

America is easing chip-export controls at exactly the wrong time

The ban on sales to China was working, and should be kept in place

Illustration: Klawe Rzeczy

Jul 31st 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

In the six months since China stunned the world with DeepSeek, its progress in artificial intelligence (AI) has continued to impress. In July alone three labs unveiled top-flight ai models, matching and in some cases even beating America’s best. The bosses of America’s leading modelmakers say that advanced ai, able to outperform the average human at all cognitive tasks, could be just a few years away. The race is not just commercial, but geopolitical: the country that gets to superintelligence first would enjoy mighty military advantages, too.

This is the backdrop against which the Trump administration has abruptly changed its mind on the export of America’s world-beating ai chips to China. In April it blocked the sales of Nvidia’s h20 chips to the People’s Republic. On July 14th the firm said it had been given permission to resume them. The U-turn came shortly after a meeting at the White House between President Donald Trump and the boss of Nvidia, Jensen Huang. Nvidia is the world’s most valuable company, and its fortunes move markets. To a president who views the S&P 500 as a personal approval tracker, that may give it sway that other firms lack. But even without the grubby optics, the decision is a grave mistake at the worst possible time.

That is because as impressive as Chinese models have been, America’s chip controls were clearly working. When Nvidia devised the h20 to comply with an earlier set of rules, it inadvertently created a chip that was hobbled for training new AI models, but perfect for running them—a process called inference. Since exports of the H20 were banned in April, even the Chinese labs that had overcome the shortage of training chips to produce world-class AI models have been unable to access enough computing capacity to offer those models to paying customers. They have had to resort to relying on outsourced hosting, and making the most of the limited quantity of AI chips produced by Huawei and other Chinese hardware firms. But the trend seems clear: without H20s, Chinese companies cannot keep up with demand.

And as AI adoption increases, having enough capacity for inference will become ever more important, making export controls even more potent. America’s ban on the export of H20s, in short, has impeded China’s progress in AI. It seems perverse for America, engaged in an arms race with China, to give up this advantage.

Moreover, rapid progress in AI argues for restricting chip sales now, even if that ends up boosting China’s hardware industry in the longer term. There is no question that blocking Chinese firms’ access to foreign inputs has stimulated demand for Chinese alternatives. It has turbo-charged innovation and the development of an alternative ecosystem in a way that even President Xi Jinping and his deep pockets could not manage. China’s domestic chipmakers remain years behind the industry’s cutting edge, but export controls have strengthened their commercial incentive to catch up. America thus faces a trade-off: it can limit China’s AI software industry today at the expense of emboldening its AI hardware industry in the longer term, or vice versa.

Mr Trump’s ai adviser, David Sacks, says allowing chip exports will make China dependent on America’s technology ecosystem, and discourage it from developing its own. The more Chinese firms use Nvidia’s chips, goes the argument, the harder it will be for Huawei and other local firms to develop a commercially viable alternative. America’s commerce secretary says he wants China to be “addicted” to American chips.

Yet given the stakes of the AI race, the risk that China’s hardware supply chain will be strengthened in the long run is worth taking. The fiendish complexity of chipmaking means catching up will take many years. And if there is even a small chance that the time-frame for AI development suggested by America’s AI leaders is correct, the race for superintelligence may have been won by 2030. Accordingly, America should do everything it can to win that race in the short term, even if that means it fails to hamper the development of China’s hardware industry in the longer term.

Nvidia’s comparison

When it comes to many of the ingredients of artificial intelligence, China measures up well against America. It has deep reservoirs of talent, data and capital, and plenty of power-generating capacity. Chips, however, are its Achilles heel. As artificial-intelligence models wow the world, and even bigger advances loom on the horizon, it is foolish for America to give its main geopolitical rival any assistance. ■

Asia | Tariffs unstitched

South Asian women will be hurt by the trade war

Unless Bangladesh and Sri Lanka strike a deal with Donald Trump

Material gainsPhotograph: GMB Akash/Panos Pictures

Jul 31st 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

ThE participation rate of women in the labour markets of South Asia is in general woefully low. The region’s garment factories, however, are exceptions. In Bangladesh and Sri Lanka around two-thirds of those behind the sewing machines are women. The industry has pulled millions of them into the workforce while spearheading the countries’ economic growth since the 1980s. But much hinges on selling cheap t-shirts and shoes to a country whose president’s favourite word is tariffs.

Workers and industrialists have been on tenterhooks since Donald Trump announced “reciprocal tariffs” on most of America’s trade partners in February. America is the largest single-country buyer of garments from the region. Sri Lanka, which still faces a tariff rate of 30% after a four-month pause runs out on August 1st, relies on garment sales for more than 40% of its export revenues. Bangladesh, the world’s second-largest producer of ready-made garments, is renegotiating the 35% tariff that Mr Trump now says will come into effect that day. “This will be a disaster for us,” says Mohiuddin Rubel, a former director of Bangladesh’s garment manufacturers’ and exporters’ association.

Since February, American buyers such as American Eagle and Walmart have put millions of dollars-worth of orders on hold. Mr Rubel’s own company has lost around 25% of his sales to America since March. A few days after Mr Trump renewed his threat of tariffs on Bangladesh on July 7th, Walmart told Iqbal Hossain, the managing director of Patriot Eco Apparel, a garment manufacturer there, to freeze $1.25m-worth of orders until more clarity emerges.

A stitch in time

Both women and men are likely to suffer. But there are fewer options for women to retrain or find other work. Unions say that temporary workers have already been laid off in Bangladesh. Lima Akhter, a 28-year-old woman who supported her family of eight by working at Patriot Eco Apparel, lost her job without notice in June, along with 40 others. “I used to pay for my children’s school fees and my parents’ medication,” says Ms Akhter. Instead, she has been obliged to borrow money from a microcredit company.

In Sri Lanka companies have been citing the proposed tariffs in order to refuse to pay salary rises or bonuses. Ranil Wickremesinghe, a former president of Sri Lanka, has warned that if they come into effect they could put over 100,000 jobs at risk. Trickle-down effects would hurt at least 2.5m to 6m dependants, says Anton Marcus of the Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital.

American brands such as Gap and Walmart have also asked manufacturers to absorb at least half of the initial 10% tariff that Mr Trump has imposed during the pause. A number of small and medium-size companies suspended production, just as they were recovering from the after-effects of the revolution that toppled Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s leader, in 2024. Over 800 businesses in the country will be affected, says Rashadul Alam Raju, general secretary of the Garment Workers Union Federation in Dhaka, the capital.

“It is difficult for a single mother to survive and pay school fees without a job,” says Kohinoor Begum, a 35-year-old garment-worker who also lost her job last month in Bangladesh. Unions complain that when women factory-workers get dismissed, they struggle to get another position. Most leave their villages for factories in their late teens. They spend years repeating the same mechanical tasks without gaining new skills.

Ahead of Mr Trump’s deadline, countries are renegotiating renewed tariff rates that may preserve some of their industry’s comparative advantage. Bangladesh is ramping up imports from America to convince the Trump administration that it can close its $6bn trade deficit. Recently the government ordered 25 Boeing aircraft as well. The Sri Lankan government says it is scheduled for another round of talks with America.

Even so, both Bangladesh and Sri Lanka will need to undergo profound change to become immune to future shake-ups. Sri Lanka could offer America targeted benefits in high-value sectors such as tech to reduce its overdependence on clothes. This would have the added advantage of shielding the industry and its workers from the volatility of global trade structures, says Thiruni Kelegama at the University of Oxford. But for now, the next payslip of thousands may depend on giving Mr Trump what it takes to seal a deal. ■

China | Grey power arising

Can pensioners rescue China’s economy?

The government is stingy and timid when it comes to retirement benefits

Photograph: Getty Images

Jul 31st 2025|HONG KONG|6 min read

Listen to this story

INSIDE BEIJING’S third ring road, Mr Li rides a scooter for FlashEx, a courier. Now in his 40s, with two school-age children, he migrated from Henan province, roughly 600km to the south. The capital’s ring roads, he has discovered, are not paved with gold. Competition has increased; fees have declined. Of the roughly 8,000 yuan ($1,100) he makes each month, he saves more than half.

People like Mr Li pose a conundrum for China’s economic policymakers. If China’s households feel insecure, they will not spend. And if they do not spend, the country’s ever more impressive industrial system will keep struggling to find customers. The lack of demand has already saddled the economy with persistent deflation: China’s factory-gate prices have fallen year on year for 33 months in a row. Falling prices can become a vicious circle, if they oblige companies to cut wages, further dampening demand.

On a recent visit to Henan, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, urged officials to strengthen social security and improve public services. Many macroeconomists agree: stronger social safety-nets would be good economically, as well as being good in themselves. On July 28th, the government took a welcome step in the right direction with a new subsidy to boost births: 3,600 yuan a year for families for each child under the age of three.

The government might look next to the other end of the life cycle. If China spent another 1trn yuan on rural pensions, it would increase GDP by roughly 1.2trn, according to Liu Shijin, who used to work for a think-tank attached to China’s cabinet. That makes pension reform effective stimulus policy, as well as worthwhile social policy. It is one of China’s best structural tools to unlock household consumption, according to Robin Xing of Morgan Stanley, a bank. The difficulty is getting the government to use it.

China is famous for its thrift. Households as a group now save over 30% of their disposable income. Migrant workers, like Mr Li, save even more: over 48%, according to one estimate, although some of that money will be spent by their family members back in their home towns.

Chart: The Economist

In the past, much of this saving was channelled into property. But purchases of flats have fallen by half since the housing market peaked in mid-2021. The saving is flowing instead into financial assets, often cash. Figures reported by HSBC, another bank, show that cash and deposits accounted for almost half of households’ financial assets in 2022, compared with less than 14% in America. These piggy banks provide peace of mind, but meagre financial returns. The paltry income households earn from their wealth is another reason for weak consumer spending, says Adam Wolfe of Absolute Strategy Research, a consultancy.

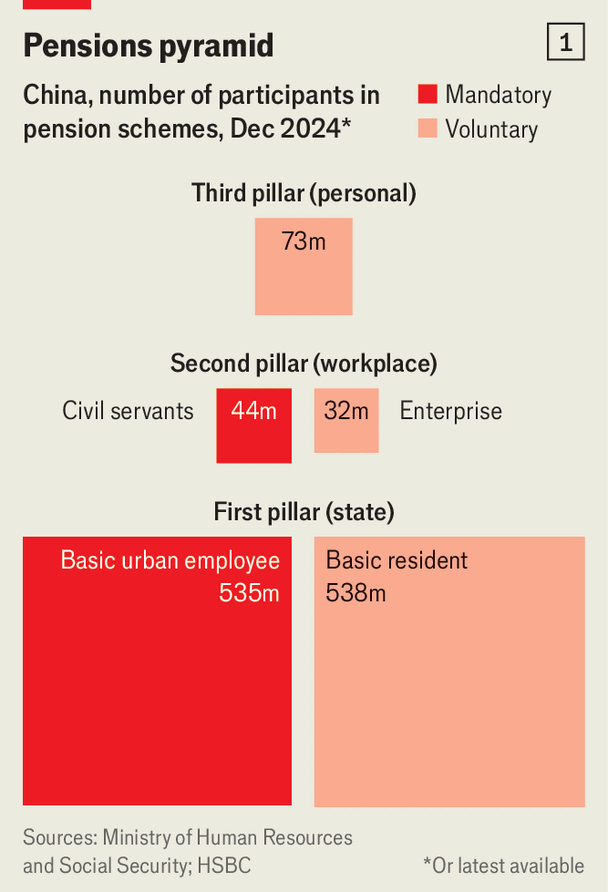

To increase spending, pension reform will have to make the system both more generous and more adventurous. The existing pension architecture, it is often said, comprises three pillars (see chart 1): state, workplace and personal, which cover more than 90% of the adult population. But it is, in fact, a less tidy assemblage of five programmes. In some schemes an individual’s contributions flow directly into assets held on their behalf. In others the link between money in and money out is much less tight. A government formula, not market returns, links past contributions to future payouts.

The government has been tinkering with many of these schemes, to improve their reach and financial returns. At the end of last year it rolled out personal pensions across the whole country, offering modest tax breaks to people who contribute up to 12,000 yuan a year to their private pension pot. Almost 73m people have signed up, but fewer than a quarter of them have paid in any money.

The government also wants the funds collected by occupational pensions (which cover about 76m people, including 44m government workers) to be invested more bravely. Because the money managers who handle these assets are typically judged annually, they play it safe, allocating only 10-15% of their portfolios to equities, so as to avoid a bad year. The result is long-term money managed with a short-term mindset, argues Bo Sun of Principal Financial Group, an investment firm. The government wants money managers to be evaluated over three years or more. That would allow them to buy more equities, which could help stabilise the stockmarket and earn higher returns over the long run.

The government is also trying to extend its mandatory social-security scheme for urban employees, which covers over 530m people, to gig workers like Mr Li and others engaged in more flexible kinds of labour. Such workers can now contribute 20% of their earnings if they wish, although many are reluctant to give up wages now for pensions later. Some e-commerce platforms have started offering to act more like regular employers, making top-up contributions for riders who divert a share of their wages into such schemes.

Chart: The Economist

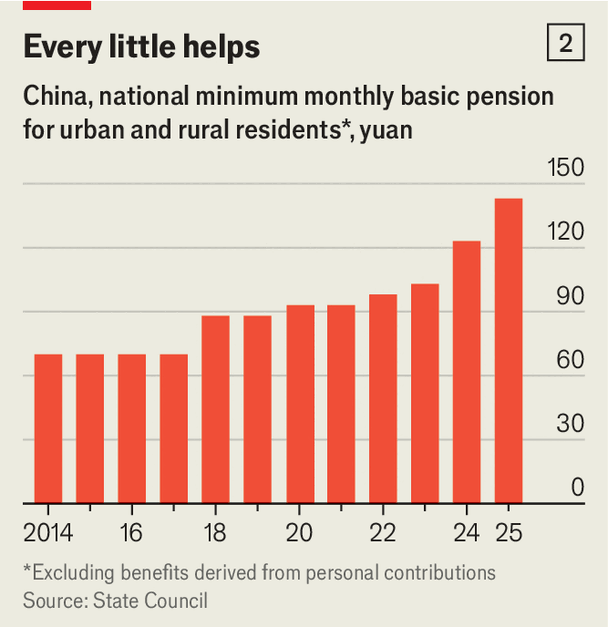

The biggest of China’s five schemes spans around 538m residents, most of them rural, who can choose to make small contributions in their younger years in return for modest benefits later in life. In March, the government said it would add 20 yuan to the minimum monthly payout of 123 yuan, which is often topped up by provincial governments (see chart 2). Behind the state schemes stands the National Social Security Fund, which manages some of the money collected, as well as holding equity stakes in state-owned enterprises, with a book value of 2.1trn yuan.

Some economists think the government should do far more. Lu Ting of Nomura, a bank, argues that increasing the monthly pension by 300 yuan would have a double benefit. The extra money would increase the spending of pensioners, who now number over 180m. It would also reduce the saving rate of the scheme’s 358m younger members who could look forward to receiving it when they retire. The extra cost would be less than 0.5% of GDP a year.

Is the government listening? In June, the Communist Party’s central committee released a set of ten opinions on “improving people’s livelihood”, covering the elderly, education, health care and more. They represent the first comprehensive livelihood policy, issued as a central document, since Mr Xi came to power in 2012, according to a government spokesman. They said China should sweeten incentives to contribute to pensions, bring more flexible workers into the fold, and make it easier to enroll in schemes where people live, not where they are registered under China’s hukou system of internal passports. The opinions were, however, disappointingly vague, failing to clarify “who is going to pay”, points out Mr Xing.

The government does not seem ready for the kind of generosity that would really drive growth. The 20-yuan addition to resident pensions offered this year and last was itself a big increase compared with past increments. The government is wary of haste, even when the shortfall in demand is urgent. In recent weeks, it increased retirement benefits for urban employees and government workers by a measly 2%. “The problem isn’t a lack of ideas—it’s institutional inertia,” argues Mr Xing. “The gap between diagnosis and delivery remains wide.”

As for Mr Li from Henan, he is not counting on pension reform to secure his retirement. “If we can’t work any more, we can go back to our home town to farm,” he says. Mr Xi tells the country’s people to look forward to “Chinese-style modernisation” and a gleaming industrial future. But many older people, like Mr Li, face the prospect of a return to the land. ■

United States | Fight or flight

What Donald Trump is teaching Harvard

Under pressure, America’s oldest university may make a deal

Illustration: Harry Haysom

Jul 30th 2025|NEW YORK|4 min read

Listen to this story

At Harvard you can study negotiation. This being Harvard, there is in fact an entire academic programme dedicated to the craft. The principles are simple. Understand your alternatives—what happens if you fight rather than compromise—and your long-term interests. This being Donald Trump’s America, Harvard itself is now the case study.

Mr Trump has turned full guns on that supposed hotbed of antisemitism and left-wing indoctrination. America’s oldest and richest university would be his most satisfying trophy and its capitulation would become a template for coerced reforms across higher education. The government has sought to review some of Harvard’s coursework as Mr Trump has pressured it to hire fewer “Leftist dopes” and discipline pro-Palestine protesters. When the university refused, his administration froze federal research grants worth $3bn and tried to bar it from enrolling foreign students.

Harvard has fought back and sued the government twice. Its many constituencies have loudly supported this resistance. Seven in ten faculty who took part in a poll by the Crimson, a student newspaper, said the university should not agree to a settlement. Yet it seems likely that Harvard will fold in the manner of Brown University and Columbia; reports suggest it will pay up to $500m.

Consider Harvard’s options. Litigation has succeeded initially: a judge paused the ban on foreign students.

Harvard had a sympathetic hearing in its lawsuit to restore government funding. Yet the university knows that it cannot count on the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority. Meanwhile, the potential damage from Mr Trump’s campaign looks both acute and existential. Losing federal funds would transform Harvard from a world-class research university to a tuition-dependent one. They constitute 11% of the operating budget and represent almost all the discretionary money available for research. Making do without while maintaining current spending levels would see the university draw down its $53bn endowment by about 2% a year. That is possible for a while, though it would erode future income and much of the endowment is constrained by donor restrictions anyway.

Already Harvard has frozen some hiring and laid off research staff. More trouble awaits. The Internal Revenue Service is considering revoking Harvard’s tax-exempt status. Elise Stefanik, a Republican congresswoman, has suggested that the university committed securities fraud when it issued a bond in April and failed initially to tell investors about the government’s demands. She wants the Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate. The Department of Homeland Security has sought records about foreign students who participated in pro-Palestine protests.

Alumni, faculty and students report pride in Harvard’s president, Alan Garber, resisting Mr Trump’s extortion scheme. Yet more and more faculty are calling for a deal, especially in medicine and science since they have the most to lose. Steven Pinker, a psychology professor, has argued for a “face-saving exit”: Mr Trump may be “dictatorial” but “resistance should be strategic, not suicidal”.

A deal similar to Brown’s would not be so hard to swallow. To restore its federal funds, that university will pay $50m to workforce-development organisations. A likelier model is the one reached with Columbia, which coughed up $200m to the government. Most of its federal funding, worth $1.3bn, was reinstated and probes into alleged civil-rights violations were closed. Viewed from the outside, the price paid by Columbia looks arbitrary—there was no explanation for how it had been calculated.

Columbia also agreed to dismantle DEI initiatives and will hire faculty specialising in Israel and Judaism, among other concessions. An outside monitor will ensure compliance. Claire Shipman, the university’s acting president, said Columbia had not accepted diktats about what to teach or whom to hire and admit.

Maybe so, but the settlement was still a shakedown. Mr Trump skipped the legal process by which the government can cancel funds. By law the administration has to offer a hearing and submit a report to Congress at least 30 days before the cut-off takes effect. None of that happened. Of course coercive, bilateral deals are Mr Trump’s métier—he has achieved them with law firms and trading partners.

Harvard has been making changes on campus that may be labelled as concessions in any eventual settlement. Some do appear designed to assuage Mr Trump. Since January the university has adopted the government’s preferred definition of antisemitism; ended a partnership with Birzeit University in the West Bank; removed the leadership of the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies; and suspended the Palestine Solidarity Committee, an undergraduate group. DEI offices have been renamed and their websites scrubbed.

Harvard’s lack of ideological diversity will not be fixed by fiat. In 2023 a Crimson poll found that less than 3% of faculty identified as conservative. Now the university is reportedly considering establishing a centre for conservative thought akin to Stanford’s Hoover Institution. Across campus it is understood that too many students seem ill-equipped to deal with views that challenge their own, says Edward Hall, a philosophy professor.

Another insight you will glean in a Harvard negotiation class is to grasp your opponent’s interests. In Mr Trump’s practice, this means bagging a deal and bragging about it. He wrote a whole book on the topic. It could go on a syllabus. ■

The Americas | A new assault

Donald Trump’s unprecedented attack on Brazil’s judiciary

He has placed sanctions on the judge leading the prosecution of Jair Bolsonaro, his ideological ally

Button down the hatchesPhotograph: Dado Galdieri/The New York Times/Redux/Eyevine

Jul 31st 2025|São Paulo|6 min read

Listen to this story

“Let this be a warning to those who would trample on the fundamental rights of their countrymen,” Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, posted on X, a social-media service, on July 30th. The would-be human-rights trampler was Alexandre de Moraes, a Brazilian Supreme Court judge. The warning came in the form of sanctions placed on Mr Moraes under the Global Magnitsky Act, freezing his assets in American banks and prohibiting him from entering the United States.

The Magnitsky Act punishes foreign officials for “gross violations of internationally recognised human rights”. It has previously been used against genocidal Burmese generals and Russian officials who murdered political dissidents. Mr Moraes has done nothing like that. His most noteworthy act is leading the prosecution of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right former president and ally of Donald Trump, who will soon stand trial on charges of plotting a coup to overturn an election he lost in 2022, which he denies.

Targeting a sitting judge in a functioning democracy is unprecedented. The sanctions come days after the State Department revoked the visas of most justices on Brazil’s Supreme Court and other officials connected to Mr Bolsonaro’s prosecution. In justifying the sanctions Scott Bessent, the treasury secretary, claimed that Mr Moraes was carrying out “an unlawful witch-hunt against US and Brazilian citizens and companies”.

Bearing down on Brazil

After the sanctions were announced, Mr Trump signed an executive order placing tariffs of 50% on many Brazilian imports from August 6th. In the order he cited the “politically motivated persecution, intimidation, harassment, censorship, and prosecution” of Mr Bolsonaro. He did not mention trade imbalances, the usual justification for tariffs, perhaps because Brazil runs a deficit with the United States.

Mr Moraes has been at loggerheads with the Trump administration and its allies since 2019. That year, the court opened what would become known as “the fake-news inquiry” to investigate misinformation on social media that affected “the honour and security of the Supreme Court and its members”. The probe was controversial from the beginning. Brazil does not have a legal definition of misinformation. By investigating, prosecuting and ruling on threats against itself, the Supreme Court demonstrated its excessive powers. Mr Moraes was appointed to lead the inquiry, bypassing the usual lottery system.

The probe was meant to last less than a year. Instead, it continues six years later and its remit has expanded to include online disinformation about Brazil’s democratic institutions. The probe is sealed, so it is unclear how many social-media accounts Mr Moraes has ordered to be taken down, or why. In April 2024 the judiciary committee of the US Congress published a report showing that Mr Moraes had ordered X to remove at least 88 accounts since 2019, usually without providing justification. In February, Mr Trump’s media group and Rumble, a video-sharing platform, sued Mr Moraes, alleging that because his rulings affected Brazilians in the United States, they constituted overreach.

None of Mr Moraes’s actions have been illegal on Brazilian terms. He is empowered by Brazil’s constitution, one of the world’s longest, which covers everything from health care to wages. It also allows Brazil’s president, state governors, the country’s bar association, trade unions, political parties and other groups to file lawsuits directly with the Supreme Court, instead of having them filter up from lower bodies. The court’s 11 justices issued over 114,000 rulings last year alone. To deal with this caseload, individual judges are allowed to make far-reaching decisions. This gives Mr Moraes and his colleagues on the bench enormous power, especially in areas where Brazil’s Congress has not legislated. Since it has yet to pass a law regulating social media, much of the enforcement has fallen to the court.

Brazilian speech law is more restrictive than that in the United States. It prohibits discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation, religion or “physical or social condition”. Penalties for slander, defamation and libel are higher when made against public officials. In 2021, while Mr Bolsonaro was in office, Congress passed a law penalising “crimes against democracy” that include “restricting the exercise of constitutional powers” through serious threats or force. Equipped with this cocktail of laws, Mr Moraes has gone after Mr Bolsonaro and some of his fans.

With flowers on a Sunday

Those who decry Mr Moraes’s pursuit of Mr Bolsonaro seem to ignore the evidence in his prosecution. Bolsonaristas attacked government buildings on January 8th, 2023, after their leader falsely claimed that voting machines had been rigged against him. Mr Bolsonaro’s allies make the riot sound like a tea-party. “It was done by old ladies, with Bibles, with flowers, with flags, by the elderly, by children, without tanks, without leaders, on a Sunday,” says Rogério Marinho, a senator for Mr Bolsonaro’s party. Any cursory search of the riot shows that it was a vandalistic orgy. On December 12th, 2022, when President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s victory was certified by Brazil’s electoral court, Mr Bolsonaro’s supporters set buses and cars alight in Brasilia, the capital. On Christmas Eve one man strapped a bomb to a fuel truck near Brasilia’s airport, but it failed to go off.

Mr Bolsonaro’s inner circle allegedly considered more thuggish actions to stay in power. According to federal police, his deputy chief of staff, Mario Fernandes, produced a plot to assassinate or kidnap Mr Moraes as well as Lula, as the president is known, and his running-mate before they could take office. The plan was allegedly printed out several times at the presidential palace in the last days of Mr Bolsonaro’s administration. It listed weapons to be used, including rifles, machineguns, grenade launchers and anti-tank rocket launchers, as well as chemical weapons to kill Lula in hospital, where he was getting check-ups. On July 24th Mr Fernandes admitted in court that he was the author of the document, but called it a habitual “risk analysis” and claimed that he had printed it out to avoid straining his eyes. He said that he did not share it with anybody.

Police also allege that lawyers close to Mr Bolsonaro drew up a decree that would have called a bogus state of emergency to in effect annul the 2022 election. On June 10th Mr Bolsonaro admitted before the Supreme Court that he had called meetings in the presidential palace to discuss the possibility of declaring a state of emergency after losing the vote. He said he quickly abandoned the idea, which received pushback from generals.

Messrs Rubio, Trump and Bessent may think that putting pressure on Mr Moraes will liberate Mr Bolsonaro. Yet their novel use of the Magnitsky Act could backfire. Lula now frames the Bolsonaro clan as “traitors”. Most Brazilians agree. Mr Moraes, who is accustomed to receiving death threats, is hard to intimidate. On the day the sanctions were announced he flew to São Paulo to watch his favourite football team play a match. ■

Middle East & Africa | Only bad options

Famine in Gaza shows the failure of Israel’s strategy

It has become an international pariah without vanquishing Hamas

Testimony to failurePhotograph: Getty Images

Jul 31st 2025|Jerusalem|4 min read

Listen to this story

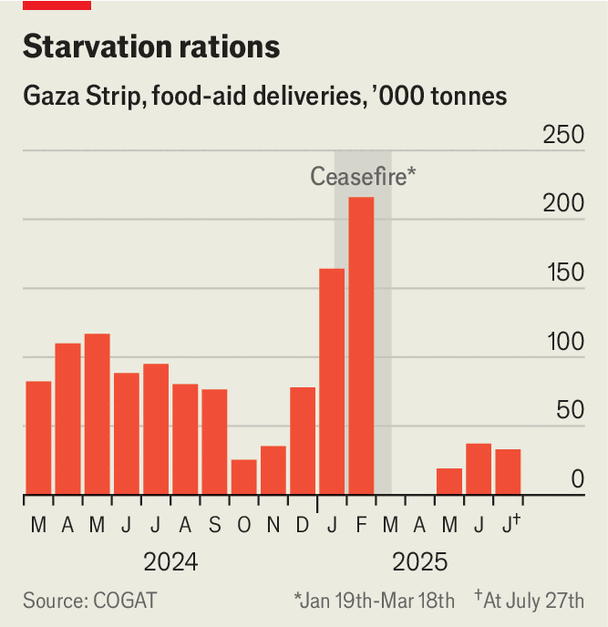

The announcement was an admission of failure. On July 26th the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) said that it would parachute food into Gaza and implement daily “humanitarian pauses” in parts of the still depopulated areas of the devastated strip, allowing international aid organisations to bring in convoys.

Four months after Israel ended the ceasefire in Gaza by closing the crossings into the territory, relaunching its military offensive and trying to replace the international aid system with an alternative supply arrangement, it has exacerbated a humanitarian crisis and drawn global opprobrium without destroying Hamas, the Islamist movement that still controls parts of Gaza. Yet beyond immediate attempts to placate international critics while continuing to pander to hardliners at home, it is unclear what will replace its failed strategy.

The decision to let in more aid followed mounting reports of starvation within Gaza and pressure from Israel’s allies, especially from the Trump administration. On July 29th the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an organisation that monitors food security around the world, said “the worst-case scenario of famine” was unfolding in the territory. It said that widespread starvation, malnutrition and disease were causing a rise in hunger-related deaths. Since April 20,000 children in Gaza have been hospitalised with acute malnutrition. On July 28th Donald Trump said there was “real starvation” in the strip.

The Israeli government still denies that Gazans are starving, calling the claims a propaganda campaign by Hamas. It insists that Hamas controls the flow of aid through the established aid organisations, a claim which the UN and other groups have consistently denied.

Replacing that system with the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF), a shadowy organisation that since late May has been distributing food at four centres staffed by American mercenaries and located inside areas controlled by the IDF, has proved disastrous. The flow of aid into the strip has slowed to a trickle. In addition, hundreds of Palestinians have been killed by the IDF on the approach routes to the centres, or have been trampled to death while queuing for food. In private, even Israel’s military chiefs have admitted that the strip is on the brink of famine and have been urging Binyamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, to let in more food.

Chart: The Economist

Aid officials say the about-face has yet to have much effect on the ground. Air drops have barely made a dent in the needs of Gaza’s 2m people, as there is no way to ensure the food reaches those who need it most. On July 29th Israeli authorities said they were allowing 200 lorries a day into the strip, still far fewer than the 500-600 that aid groups say are needed to meet basic needs. Half of all planned convoys were still not being authorised, said aid workers. Several lorries that made it into the strip were stopped by crowds of desperate people and looted en route. To supply the vast quantities of aid necessary to stave off famine, says Tom Fletcher, the UN’s emergency relief co-ordinator, quicker clearances and safer routes are needed.

Mr Netanyahu promised in a statement in English that Israel “will continue to work with international agencies” and “ensure that large amounts of humanitarian aid flows into the Gaza Strip.” In Hebrew he was much less emollient, promising his base that “in Gaza we are continuing to fight” and that “we will achieve our aim of destroying Hamas.” The aid entering Gaza, he said, would be “minimal”.

Besides its propaganda purpose, the conflicting messaging reflects a lack of clarity. Mr Netanyahu has manoeuvred Israel into a corner where it has few options, much less a coherent strategy. Unofficial talks about a ceasefire have continued since indirect talks between Israel and Hamas broke down on July 24th. America is still urging Israel to make a deal that ends the war. Given intensifying international condemnation of Israel, Hamas may feel it can drive a harder bargain. But a deal that leaves Hamas with any degree of power in Gaza would be unacceptable to Israel.

Other plans being floated by Mr Netanyahu’s government are equally untenable. Opposition from the IDF has blocked the government’s idea of forcing the entire population into a “humanitarian city” on a sliver of Gaza’s territory. Annexing parts of the strip or laying siege to the remaining areas inhabited by civilians would both worsen the already dire humanitarian situation and prompt louder global outrage without finishing off Hamas.

Airing such drastic ideas pleases Mr Netanyahu’s far-right coalition partners. Their power to rattle his government has been diminished now that the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, is in recess until mid-October. Mr Netanyahu could use this period for moves that would enrage them, such as agreeing to a ceasefire. Yet for now, he is playing for time. For starving Gazans, that means any relief may be temporary. ■

Photograph: Getty Images

Editor’s note (July 29th): This photograph, which originally illustrated our leader, was wrongly captioned. It omitted to say that Muhammad al-Matouq, an emaciated 18-month-old child, suffers from a pre-existing condition. We have replaced it because we are unable to know to what extent the decline in his health was caused by the incipient famine in Gaza, his lack of medical care or the inevitable progression of his underlying illness.

Europe | Lady killers

Ever more Ukrainian women are joining the army

A growing group that is changing society

An equal shotPhotograph: AFP

Jul 31st 2025|Komyshuvakha|3 min read

Listen to this story

Commander Twig and her girls pull into a café near the Zaporizhia front and order non-alcoholic mojitos. In the distance is the occasional thud of outgoing artillery. The word “killing” implies murder, which would be wrong, says Twig’s comrade, Titan; she prefers to call her job “liquidating Russians”. The five-strong unit is one of a small but growing number of all-female drone crews. Genitals are irrelevant to flying drones, notes Maria Berlinska, a campaigner for military women.

Unlike men, many of whom are unwilling conscripts, all Ukrainian women under arms are volunteers. They number about 100,000 of the country’s 1m military personnel. Some 5,500 are on the front line, says Oksana Grygorieva, a gender adviser to the armed forces. They include medics, drivers, drone crews and others. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 about 15% of armed forces staff were female. The army’s huge growth means that though the share is smaller, the number of women serving has more than doubled.

Read more of our recent coverage of the Ukraine war

Perhaps 20% of the students in military high schools and universities are women, says Ms Grygorieva—a huge shift. Only in 2018 did Ukrainian legislators open such schools to women, and remove other restrictions on the roles they could fulfil. Laws against sexual harassment in the armed forces are now being tightened. The struggle is to ensure women “are not treated like second-class soldiers”, says Ms Grygoieva. Formal barriers may have gone but informal ones remain, says Katerina Prymak, head of Veteranka, which campaigns for military women’s rights.

Alina Shukh initially tried to enlist in the prestigious Azov Brigade, but they said they had “no positions for women”. Instead she joined the more egalitarian Khartiia Brigade. As a former professional heptathlete, Sergeant Shukh notes, she is stronger than most male soldiers. In any case, says Olha Bihar, who commands an artillery unit, technology is changing warfare: the best killer may now be a tiny drone pilot with dexterous fingers. “All our stereotypes are changing,” she says; she hopes, some day, to be minister of defence.

Ms Berlinska has been pushing to open more roles to women since Russia’s initial invasion in 2014. Invisible Battalion, a research project she helped found, revealed that many women were fighting despite laws barring them from combat, registering instead as cooks and cleaners. “Every war has boosted technological progress and the emancipation of women,” she says, and this war is no different. There has been no political debate about conscripting women. It might be risky, says Yevhen Hlibovytsky of the Frontier Institute, a think-tank. Ukrainian leaders may “fear that the Russians would smell strategic weakness” if the topic were opened. But with yawning gaps in recruitment, the idea cannot be ignored for ever.

Not everyone is on board. In a command centre near Komyshuvakha, eight men in T-shirts and slippers sweat in front of live drone feeds. A banner on the wall depicts a naked, sword-wielding maiden. Asked why he has no female soldiers, the commander curses a blue streak: the front, he thinks, is no place for a woman. ■

Business | Schumpeter

Who will pay for the trillion-dollar AI boom?

A technological revolution meets a financial one

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Jul 31st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

America’s biggest technology companies are combining Silicon Valley returns with Ruhr Valley balance-sheets. Investors who bought shares in Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft a decade ago are sitting on eight times their money, excluding dividends. Spending on data centres means the firms possess property and equipment (accounting-speak for hard assets) worth more than 60% of their equity book value, up from 20% over the same period. Add the capital expenditure of these firms during the past year to that of Amazon and Oracle, two more tech giants, and the sum is greater than the outlay of all America’s listed industrial companies combined. Jason Thomas of Carlyle, an investment firm, estimates that the spending boom was responsible for a third of America’s economic growth during the most recent quarter.

This year companies will spend $400bn on the infrastructure needed to run artificial-intelligence (AI) models. Predictions of the eventual bill are uniformly enormous. Analysts at Morgan Stanley reckon $2.9trn will be spent on data centres and related infrastructure by the end of 2028; consultants at McKinsey put it at $6.7trn by 2030. Like a bad party at a good restaurant, nobody is quite sure who will pick up the tab.

Much of the burden will fall on big tech’s bottom line. Since 2023 Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft have divided $800bn of operating cashflows roughly evenly between capex and shareholder returns. This goldilocks capital allocation, which combines a building boom with a trip to the bank, is unprecedented even among their own ranks. Amazon’s shareholders are paying for huge capex bills but have been starved of returns; Apple investors have benefited from vast share buy-backs but are worried that the company’s lack of investment means it is falling behind on AI.

But capex is growing faster than cashflows. Morgan Stanley’s calculations indicate a $1.5trn “financing gap” between the two over the next three years. It could be bigger if advances in the technology escalate spending further and kill existing cash cows. Conversely, if companies are slower to adopt AI than consumers, big tech will struggle to earn a quick return on its investment; shareholders might then demand a greater portion of their earnings to compensate for this sluggish growth.

More certain than the size of the financing gap is the type of investors looking to fill it. The hot centre of the AI boom is moving from stockmarkets to debt markets. That is surprising since the attitude of the biggest tech firms to debt has been essentially German. They are much less beholden to their bankers than telecoms outfits were at the turn of the century, during the dotcom mania. Fortress balance-sheets are prized. Large bond issuances have been outweighed by even larger piles of cash. (If the “magnificent seven” tech firms pooled their liquid financial assets and formed a bank, it would be America’s tenth-biggest.)

Slowly, this is changing. During the first half of the year investment-grade borrowing by tech firms was 70% higher than in the first six months of 2024. In April Alphabet issued bonds for the first time since 2020. Microsoft has reduced its cash pile but its finance leases—a type of debt mostly related to data centres—nearly tripled since 2023, to $46bn (a further $93bn of such liabilities are not yet on its balance-sheet). Meta is in talks to borrow around $30bn from private-credit lenders including Apollo, Brookfield and Carlyle. The market for debt securities backed by borrowing related to data centres, where liabilities are pooled and sliced up in a way similar to mortgage bonds, has grown from almost nothing in 2018 to around $50bn today.

The rush to borrow is more furious among big tech’s challengers. CoreWeave, an ai cloud firm, has borrowed liberally from private-credit funds and bond investors to buy chips from Nvidia. Fluidstack, another cloud-computing startup, is also borrowing heavily, using its chips as collateral. SoftBank, a Japanese firm, is financing its share of a giant partnership with Openai, the maker of ChatGPT, with debt. “They don’t actually have the money,” wrote Elon Musk when the partnership was announced in January. After raising $5bn of debt earlier this year xai, Mr Musk’s own startup, is reportedly borrowing $12bn to buy chips.

This means the technology revolution is increasingly coming into contact with a financial one. Those at the apex of Silicon Valley are not the only elites in the West who, after spending decades perched in the realm of ideas, have decided that the physical world is where it’s at. Private-equity firms are refashioning themselves as lenders to the real economy. The resulting balance-sheet transformation has been, if anything, more dramatic than the one in Silicon Valley. Data centres produce large amounts of debt. This sits easily on the huge balance-sheets managed by these outfits, which are often funded by life-insurance policies. Like big tech, private markets are increasingly concentrated. Tech firms are raising capital because they think that the gains from AI will be concentrated among a few players. Investors are lending to them because they know the same thing is true on Wall Street.

Railroaded

This symbiotic escalation is, in some ways, an advert for American innovation. The country has both the world’s best AI engineers and its most enthusiastic financial engineers. For some it is also a warning sign. Lenders may find themselves taking technology risk, as well as the default and interest-rate risks to which they are accustomed. The history of previous capital cycles should also make them nervous. Capex booms frequently lead to overbuilding, which leads to bankruptcies when returns fall. Equity investors can weather such a crash. The sorts of leveraged investors, such as banks and life insurers, who hold highly rated debt they believe to be safe, cannot. ■

Business | Wham, bam, monogram

Can Bernard Arnault steer LVMH out of crisis?

Investors are starting to call for the luxury conglomerate to break itself apart

Photograph: Getty Images

Jul 26th 2025|Paris|6 min read

Listen to this story

Louis Vuitton’s new 17,000-square-foot development in Shanghai is, quite literally, the luxury brand’s Chinese flagship. The structure, which serves as store, restaurant, museum and billboard, is shaped like a giant boat, its hull emblazoned with Louis Vuitton’s monogram print. To some, it is also a metaphor for Louis Vuitton’s parent company, LVMH, which is floundering in China and beyond. Is it a superyacht headed for promising new waters, asks Flavio Cereda-Parin of GAM, an asset manager, or “Titanic 2.0”?

Four decades of dealmaking have turned LVMH into a luxury colossus. The group is made up of 75 independent maisons, from fashion labels such as Louis Vuitton and Dior to booze brands like Hennessy and Moët & Chandon, alongside watchmakers, hotels, retailers and more. Last year these brought in €85bn ($100bn) in sales, making LVMH around four times as large as the industry’s two other big conglomerates, Kering and Richemont. Its creator, Bernard Arnault, was perhaps the first to recognise that combining luxury brands under one roof could bring significant economies of scale by conferring negotiating power with advertisers, landlords and suppliers, and helping to entice and retain talent. Over the past decade alone Mr Arnault, referred to as “the wolf in cashmere”, has devoured a high-end jeweller (Tiffany & Co), a luxury-hotel chain (Belmond) and a premium luggage brand (Rimowa).

LVMH rode the luxury boom that began around the turn of the millennium, as monied middle-class shoppers across the globe bought posh frocks and pricey bags by the trunk-load. According to Bain, a consultancy, global spending on personal luxury goods quadrupled between 2000 and 2023, when LVMH’s market value reached its peak of around €450bn, briefly making Mr Arnault the world’s richest man.

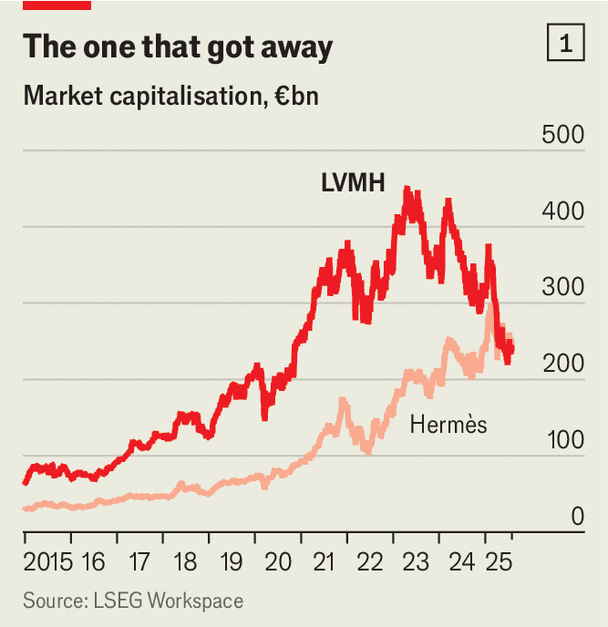

Chart: The Economist

Much has changed since then. On July 24th LVMH reported that its revenue in the first half of 2025 fell by 4%, year on year, with net profit plunging by 22%. Shoppers in America and China, the two biggest markets for luxury wares, are cutting back spending. American tariffs on European goods have not helped. LVMH’s market value has fallen by more than a quarter over the past year, to less than €250bn. Hermès, a luxury brand Mr Arnault tried and failed to buy, and has eyed with envy ever since, has taken LVMH’s crown as the most valuable company in the industry, despite generating only €15bn in sales last year (see chart 1). Adding insult to injury, the Arnault family, which has topped France’s rich list since 2017, has also been dethroned by the Hermès clan. Can Mr Arnault turn the ship around?

LVMH can’t blame the economic environment for all its woes. It raised prices enormously in the post-covid “revenge shopping” boom, irking some customers. The price of Louis Vuitton’s Speedy 30 canvas tote bag has more than doubled since 2019, for example, while the average price of personal luxury goods in Europe has increased by just over 50%, according to HSBC, a bank. Only a handful of designers, including Chanel and Gucci, have raised prices more.

A series of scandals has also damaged the image of some of its brands. Moët Hennessy, LVMH’s drinks division, has recently faced accusations of sexual harassment, bullying and unfair dismissal by former employees (which it denies). On July 14th an Italian court placed Loro Piana, an LVMH label that sells cashmere sweaters for over $1,000 apiece, under judicial administration for using suppliers that allegedly violate labour rights. Dior faced similar investigations last year. LVMH’s response has been half-hearted: “Transparency, control, and management of this whole ecosystem can sometimes prove a bit difficult,” it said recently.

Mr Arnault is trying to steer to calmer waters. New bosses have been put in charge of the booze, watches and retailing units. The appointment of Jonathan Anderson as the new creative director of Dior has been cheered by fashionistas. Some investors, however, worry that the problems are deeply rooted. One concern is that decades of pushing fancy clothing and accessories not just to the super-rich but also the merely well-off has made LVMH’s brands more vulnerable to economic cycles and dented an image of exclusivity. Even Louis Vuitton, the firm’s crown jewel, has not been immune. Analysts at HSBC term the brand “schizophrenic” for its attempt to peddle entry-level goods like chocolate and make-up alongside ultra-pricey handbags and luggage.

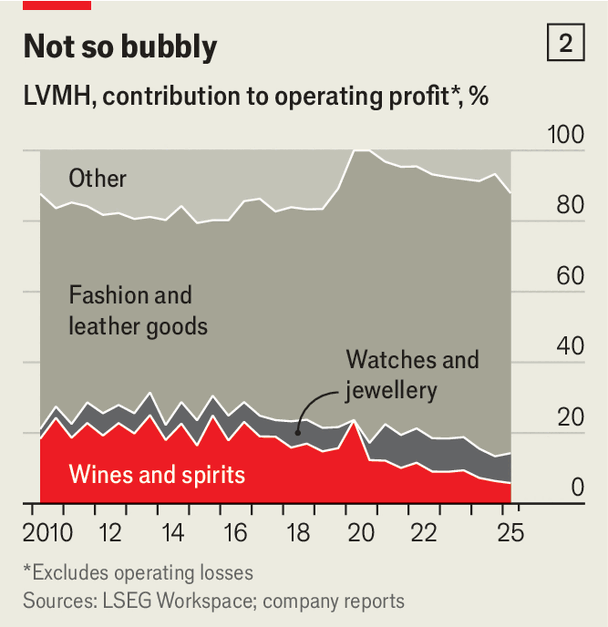

The outlook for Moët Hennessy is more worrying still. As profits have shrunk, the division has announced thousands of job cuts. Analysts point out that the young aren’t drinking as much as older generations, and when they do they tend to shy away from cognac, which makes up much of LVMH’s booze business. The wines-and-spirits division now contributes less than 10% of LVMH’s operating profits, down by roughly half in a decade (see chart 2).

Chart: The Economist

By contrast, Hermès, which has remained focused on selling fashion to the exceedingly wealthy, has continued growing handsomely. Its market value as a multiple of its net profit is now more than twice as high as for LVMH. Brunello Cucinelli, another purveyor of ultra-luxe fashion, is valued at a similar multiple to Hermès. If Louis Vuitton were to be valued at such a multiple, it alone would be worth significantly more than the entirety of its parent company.

That has led some to call for a break-up of LVMH. On July 25th reports emerged that it was exploring a sale of Marc Jacobs, a fashion label founded by a former creative director of Louis Vuitton. A bolder move would be jettisoning the troubled drinks business. Diageo, owner of tipples from Guinness to Johnny Walker, already controls a third of Moët Hennessy and has in the past expressed interest in taking the rest of it off LVMH’s hands. The British firm is currently grappling with its own slump in profits and recently parted ways with its chief executive, but analysts speculate that it could make a deal work by selling off its beer business at the same time.

Mr Arnault, aged 76, is navigating all this while making plans for a transition at the helm. He clearly intends to keep the enterprise under family management. All five of his children work in different corners of his empire under the tutelage of experienced executives. His daughter Delphine, who has been given the job of turning around Dior, is his eldest and the only of his offspring on the executive committee of LVMH, making her the most likely candidate to succeed her father. Yet there are other possibilities. In February Alexandre was parachuted in as the deputy head of Moët Hennessy. In March Frédéric was put in charge of Loro Piana.

Mr Arnault refuses to answer questions on the topic of succession. Having raised the age limit for his job from 75 to 80 three years ago, he raised it again to 85 earlier this year. That may mean he will wait until he has steadied the ship before relinquishing control. Even then, some investors question whether it is possible to replace the man who created the modern luxury industry. Mr Arnault still has plenty to do before he hangs up his captain’s hat. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Japan’s dealmaking machine revs up

Private equity is enjoying a renaissance in an unlikely place

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Jul 31st 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

The corporate raiders of the private-equity (PE) industry have been memorably compared to invading barbarians. But the industry is more usefully described as a machine, which converts investors’ money into deals, deals into profitable divestments (or “exits”), and exits into investor returns. When running well, this contraption gathers a momentum of its own. Profitable exits generate handsome returns, which tempt investors to pump in more capital, enabling further dealmaking.

Unfortunately, private equity is not running well in America. Funds are struggling to exit profitably. Deal volumes have slumped. And new capital has become harder to raise: it could fall in 2025 for the third year in a row. What was once a dominant and successful model has become sluggish and unreliable, like one of Detroit’s infamous gas-guzzlers from the 1970s.

Across the Pacific, though, is a machine roaring back to life. In Japan the number of private-equity deals has doubled since 2019, and their value has tripled. Mergers and acquisitions reached a record $232bn in the first half of 2025. Western raiders such as Ares, Carlyle and Apollo are opening new offices in Tokyo, or expanding old ones. Japanese PE is having a “major renaissance”, proclaimed bigwigs at KKR, another titan, last year.

Three things explain the contrast between the world’s biggest PE market and its hottest one. First is value. Like Detroit’s disappointing cars in the 1970s, American firms are not especially affordable. The enterprise value of American listed companies is 11 times their operating profit (less depreciation and amortisation). In Japan, the median firm costs only seven times its operating profits.

Japanese firms are cheap partly because their managers tend to squander shareholders’ capital. Many companies have giant cash hoards and plenty of inessential assets sitting around. But that drawback is also an opportunity. In America, tuning up companies’ operations is hard work. In Japan simple rationalisations would reap massive returns. The median listed firm holds cash worth 21% of its total assets, compared with 8% for American public companies.

The second flaw in American PE is that money pumped in often cannot get out. Many deals were struck in 2020-21 when interest rates were low. The industry has struggled to adapt to tighter monetary policy, just as Detroit struggled to adapt to tighter fuel-efficiency standards. Higher interest rates have reduced the value of the bought-out companies. They have also raised the cost of financing the deals. Yet many funds, having made lofty promises to investors, are now unwilling to sell at diminished valuations, for fear of realising losses. That has created an exit backlog for American PE funds, which have become slower to pay investors.

In Japan, by contrast, the pipes are less clogged. Exits are 68% above the 2019-23 average, according to Bain (although they remain short of the highs of a decade ago). Big-ticket listings, such as the 2023 sale of Kokusai Electric, a maker of chip tools that is backed by KKR, have increased confidence. Japan’s low interest rates have helped, too.

The third trend favouring Japan is surprising: deglobalisation. The rise of protectionism is rattling Japan’s many exporters. But Japanese PE has one big advantage over its American counterpart: it benefits from the retreat from China. As the risk of doing deals in the People’s Republic has grown, global PE funds have shuffled their Asia allocations away from China towards its biggest neighbours, Japan and India. China’s appeal may improve if its stockmarket continues to rally. But fear that Chinese investments could attract bad press or fall on the wrong side of a geopolitical dust-up has made many PE investors skittish. Greater scrutiny of Chinese investments has fuelled the trend towards markets like Japan, says Jim Verbeeten of Bain.

The contrast between America and Japan may not last for ever. If American interest rates fall, its PE industry could recover, just as Japan’s progress could sputter if the country’s central bank resumes raising rates. Recalcitrant managers in Japanese firms could still frustrate PE’s ambitions. Efforts in America to bring PE to the masses may let the industry sell assets to risk-happy retail investors, clearing the pipes. But for now, Japan’s dealmaking machine looks as cheap, nimble and reliable as a trusty Corolla or a Civic, while American PE remains a bit of a clunker.■

Science & technology | Well informed

Can you overcome an allergy?

Treatment is improving, even for the most dangerous

Illustration: Cristina Spanò

Jul 25th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

ALLERGIES Are on the rise. Every year more people clog up in springtime or succumb to itchy eyes in the presence of pets. In America the share of children with food allergies rose from 3.4% in 1997 to 5.8% in 2021, and there were similar increases elsewhere. But treatments allowing people to manage their allergies—even the most dangerous ones—are becoming increasingly effective, accessible and safe.

Allergies arise when the immune system gets confused. Normally tasked with protecting the body from pathogens, in people with allergies it also reacts to harmless irritants, or allergens. In overactive immune systems, proteins responsible for recognising dangerous invading parasites, known as immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies, start to become sensitive to allergens, too.

This can cause them to raise the alarm each time they come into contact with the allergen, which prompts the body to produce a signalling chemical known as histamine. When the body is under threat from a parasite, histamine can help expel it by producing mucus and provoking coughing. But for people with allergies, the response can go overboard, causing allergic symptoms such as wheezing and hives. In the worst case, histamine can provoke a whole-body reaction known as anaphylactic shock, which can block the airways and cause suffocation.

Desensitisation is possible. A family of treatments known as immunotherapies work by repeatedly exposing the body to tiny and gradually increasing amounts of allergen. For common allergens, such as pollen and dust mites, immunotherapy—in the form of drops, shots or tablets—is now common, and highly effective for most people.

Progress has been slower for food allergies, in part because they carry a higher risk of anaphylaxis. The outlook has started to brighten. In 2020 America’s Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral immunotherapy for children with peanut allergy, a powder containing peanut protein. Children who take the powder with food react less, but the increased dosage must be given under medical supervision to avoid reactions and children should still follow a strict peanut-free diet.

Options that could allow patients to increase their tolerance more safely are on their way. Companies are developing immunotherapies based on small fragments of allergen proteins called peptides. These seem to increase tolerance to the allergens without setting off harmful immune reactions.

Another avenue is blocking IgE antibodies. In a trial in 2024, 79 of 118 people with allergies to several foods were able to ingest 600mg of their allergens after taking a monoclonal antibody called omalizumab for 16 to 20 weeks, compared with only five of the 59 participants in the control group. As patients must keep taking omalizumab to feel its effects, some researchers hope to prescribe it to patients while building their tolerance through regular or peptide immunotherapy.

The burst of innovation is particularly good news for allergic adults. Because the immune system becomes less flexible with age, adults are harder to treat than children and are often excluded from immunotherapy trials. This, too, is changing. The omalizumab trial from 2024 included a small number of adults, and in April an adult-only trial showed that standard oral immunotherapy, done carefully over months, could build patients up to a dose of four daily peanuts. ■

Culture | #1 Also Rises

Hemingway remains the most famous 20th-century American novelist

A much-imitated style, celebrity fans and a life-turned-myth all help

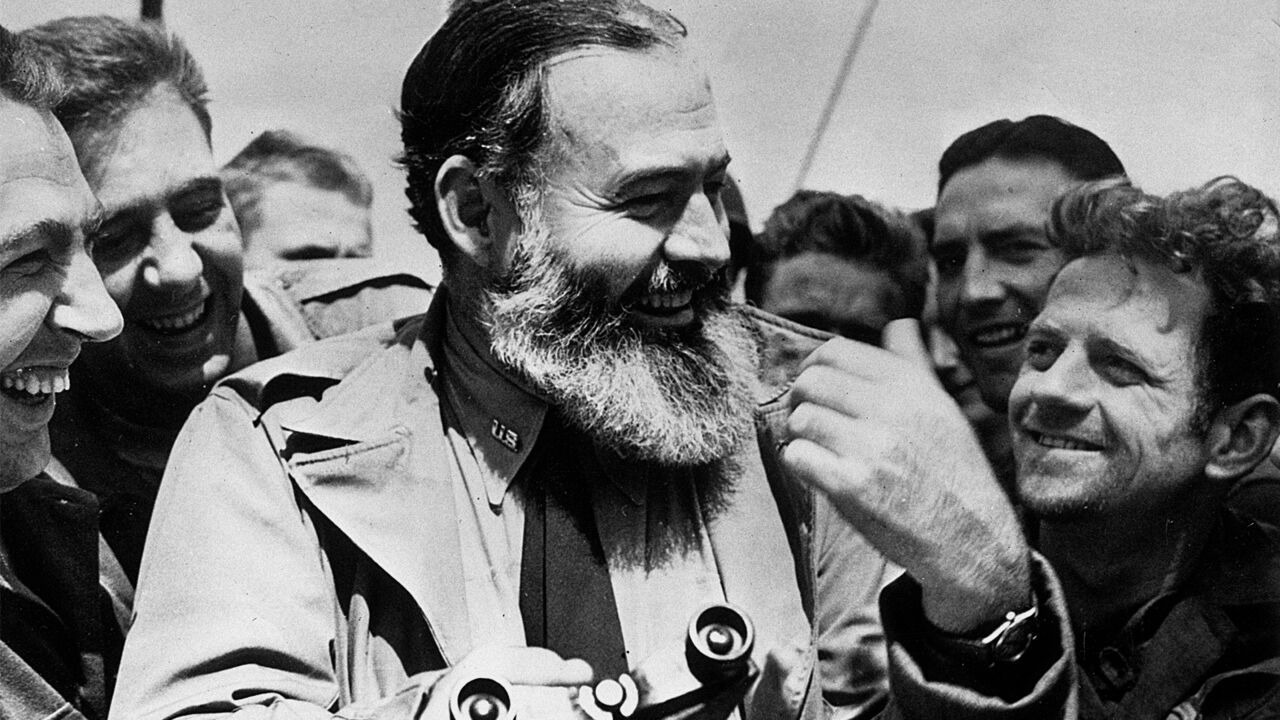

Photograph: Getty Images

Jul 28th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

IN the early 1920s Ernest Hemingway was a little-known journalist slumming around Europe and getting into absinthe-fuelled scrapes. Then, a century ago, in 1925, he published “In Our Time”, a book of short stories; in July of that year he started working on “The Sun Also Rises”, his first novel, which fictionalised his antics. It became the most celebrated book about the “Lost Generation” in post-war Europe.

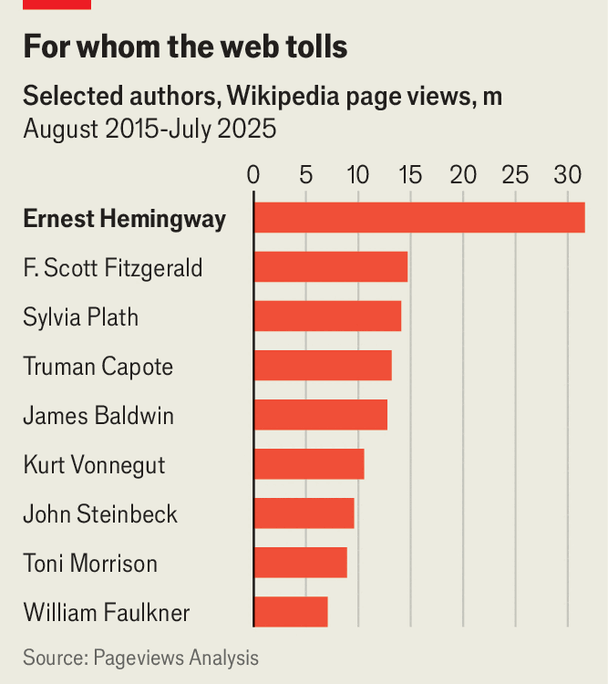

Hemingway became famous in the same way one of his characters described going bankrupt: “gradually and then suddenly”. Eight other novels and novellas followed, as did Pulitzer and Nobel prizes. He remains the most famous American novelist of his century, judged by mentions in Google’s corpus of books. His Wikipedia page also gets more views than those of his contemporaries, including F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Steinbeck (see chart). Why?

Chart: The Economist

There are three reasons. First, nobody had written like him before. A short clean sentence is a fine thing. But if the writer has his story straight and his words true he can go long and hard as a bull after a picador and to hell with big words and adverbs and commas. He also knew what to leave out, as he explained: “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them.” This lean style influenced writers of fiction—notably Norman Mailer, Cormac McCarthy and Raymond Carver—as well as journalists. Joan Didion’s spareness reads like sober Hemingway.

Second, his heroes attracted famous admirers. He defined courage as “grace under pressure”: martially, for the soldier Frederic Henry in “A Farewell to Arms”; physically, for the fisherman Santiago in “The Old Man and the Sea”; or sportingly, for the titular cuckolded character in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”, who becomes a fearless hunter. In 1955 John F. Kennedy asked for Hemingway’s permission to use this definition in “Profiles in Courage”, which won the Pulitzer prize for biography.

John McCain’s favourite novel was “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (1940), about the Spanish civil war, which he quoted in a posthumous book: “The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.” Barack Obama, a fan of the same novel, mentioned it in his eulogy to McCain. Less credibly, Donald Trump has dubbed himself the “Hemingway of 140 characters”.

Third, and perhaps most important, Hemingway’s life became legend. He married four times, drank hard, feuded with rivals, was wounded in the first world war, reported on the Omaha Beach landings in the second, ran with the bulls in Spain and survived a plane crash in Africa. But beneath the bravado his ego was fragile; he sometimes swapped gender roles in bed and suffered from depression. He was one of seven in his family to commit suicide. That has provided ample material for biographies and documentaries, including a six-hour series by Ken Burns in 2021.

But adaptations of his work are scarce. Fitzgerald and Steinbeck enjoy higher ratings and more reviews on Goodreads, a website. Perhaps Hemingway’s stoical heroes—and hints of sexism and racism, at least in the voices of some characters—are becoming old-fashioned. If so, he may end up like Lord Byron and Oscar Wilde: read keenly by a few, read about by many. ■

Obituary | Time to transubstantiate!

Tom Lehrer found matter worth roasting everywhere he looked

America’s best modern satirist died on July 26th, aged 97

Photograph: Getty Images

Jul 31st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

When he suddenly stopped, and the output dropped, he was presumed dead. No, Tom Lehrer replied. Just having fun commuting between the coasts, teaching maths for a quarter of the year, ie the winter, at the University of California in sunny Santa Cruz, and spending the rest of the time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, being lazy. Never having to shovel snow; never having to see snow. And, being said to be dead, avoiding junk mail.

Yet how famous he had been in the 1950s and most of the 1960s! He had sold his entire first song collection, recorded and mailed out by himself, and about half a million of those that came afterwards. The word spread like herpes. One album reached No.18 on the Billboard chart. Oh fame! Oh accolades! He had toured the world and packed out Carnegie Hall. Yes, they really panted to see a clean-cut Harvard graduate in horn-rimmed glasses pounding at a piano and singing: sometimes stern, sometimes morose, but often joyose, as he twisted in the knife.

Anything could be his victim; nothing was sacred. In his love songs lovers told the truth, begging for agility while they still had facility, and admitting “I will hate you, when you are old and gray”. Nostalgia for “My Home Town” was shredded when the son of the mayor was an arsonist and the lovely girl next door now charged a fee “for what she used to give for free”. “National Brotherhood Week” was a fine idea; everyone should love their neighbour, even him, though he was Jewish (“and everybody hates the Jews”):

Be nice to people who

Are inferior to you

It’s only for a week, so have no fear

Be grateful that it doesn’t last all year!

As for spring, everyone loved it; he did himself, dearly. Skittles and beer, sunshine, all right with the world, and he and his sweetheart walking out each Sunday, “Poisoning Pigeons in The Park”.

Yet shadows fell across this pretty landscape. One was pollution, with “the halibuts and the sturgeons being wiped out by detergeons”. The other was war. World War III was as vivid in the 1950s as the world war just past. He had spent a brief time at Los Alamos, “where the scenery’s attractive and the air is radioactive”, doing not much. In 1955-57 he was at the National Security Agency, aka No Such Agency, to do his army service, having waited til the world was calm first. It could not stay calm for long. A soldier told his mom he was off to drop the Bomb, “so don’t wait up for me”, but reassured her he would return “when the war is over, an hour and a half from now”. The blessing of a nuclear war, however, was that everyone would burn, fry or bake together, so there would be no more grieving: “We Will All Go Together When We Go!”

And go where? Any institution that thought it knew ought to market itself in a modern way. Hence his most controversial song, “The Vatican Rag”, set indeed to ragtime:

Get in line in that processional,

step into that small confessional;

there the guy who’s got religion ‘ll

tell you if your sin’s original.

He liked it when he touched a nerve; more so when he severed a limb. His audiences did not have to applaud or agree with him, just laugh at his songs. Though he campaigned for George McGovern, he was more universalist than of the political left. But as the left splintered in the early 1960s, and as Vietnam got too serious for his songs, it was harder to write. He disliked the grammatical sloppiness of the counter-culture, and even more their air of moral superiority. “We are the folksong army, every one of us cares. We all hate poverty, war and injustice, unlike the rest of you squares.” Rather than anger, his deepest emotion was chagrin.

So he stopped, though with a flurry in the mid-1960s when he wrote songs for various TV shows. And he went back to being what he truly was, a studious mathematician let dangerously loose on a keyboard.

His childhood had been a breeze of maths and music, with a preference for Broadway shows. He entered Harvard at 15 and graduated at 18, the sort of student who brought books of logical puzzles to dinner in hall, and, on the piano in his room, liked to play Rachmaninov with his left hand in one key and his right a semitone lower, making his friends grimace. He seemed bound for a glittering mathematical career, but then the songs erupted, written for friends but spreading by word of mouth, until he was famous. He wrote each one in a trice and performed, increasingly, in night clubs. By contrast his PhD, on the concept of the mode, vaguely occupied him for 15 years before he abandoned it.

Maths still infiltrated his songs. In “New Math” he pilloried a modernised teaching system, “so very simple, that only a child can do it!” Another favourite skewered Nikolai Lobachevsky, the “inventor” of hyperbolic geometry, whose secret was “Plagiarise! Let no one else’s work evade your eyes!” Maths influenced the songs in subtler ways, too, appealing to his love of pattern, rhyming and making things fit. These too were puzzles to solve.

Did he ever have hopes of extending the frontier of scientific knowledge? Noooooo, unless you counted his Gilbert & Sullivan setting of the entire periodic table. He would rather retract it, if anything. He still taught maths, along with musical theatre, and that was his career. He had never wanted attention from people applauding his singing in the dark. His solitary, strictly private life made him happy; to fame he was indifferent. In 2020 he told everyone they could help themselves to his song rights. As for him, he returned to his puzzle books, as if he had never strayed. ■