The Economist Articles for Aug. 4th week : Aug. 24th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.08.15조회수63 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Aug. 4th week : Aug. 24th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | President Unpredictable

How to win at foreign policy

Donald Trump’s capricious dealmaking destabilises the world

Aug 14th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

WHEN DONALD TRUMP meets Vladimir Putin in Alaska it will be the seventh time the two have talked in person. This time is different, though. Since their last sit-down, Mr Putin has launched an unprovoked war, lost perhaps a million Russian soldiers (dead and wounded) and inflicted ceaseless misery on Ukrainians in pursuit of an imperial dream.

Undaunted, Mr Trump hopes to get in a room with a wily dictator, feel him out and forge a deal. It is the biggest test yet of his uniquely personal style of diplomacy. It is also a reminder of how unpredictable American foreign policy has become. Will Mr Trump be firm, making clear that America and its allies will do what it takes to guarantee Ukraine’s sovereignty? Or will he be in such a rush to reopen business with Russia that he rewards its aggression and leaves Ukraine vulnerable to future attacks? As everyone clamours for the president’s ear, no one knows what he will do.

At the beginning of Mr Trump’s second term his supporters had a theory about how he would wield American power. Rather than relying on deep relationships and expertise, he would rely on his gut. As a master negotiator with a knack for sensing what others want and fear, he would cut through the waffle and apply pressure ruthlessly. Everyone wants access to American markets. By threatening to shut them out, he would force recalcitrant foreigners to end wars and reset the terms of trade to America’s advantage. Career diplomats and experts would be replaced by rainmakers. Yes, his transactional approach might foster a bit of corruption. But if it brought peace in Ukraine or Gaza, who cared?

Alas, there are drawbacks to this approach. Using tariffs as a weapon hurts America, too. More fundamentally, junking universal principles for might-makes-right repels friends without necessarily cowing foes. And the substitution of presidential whim for any coherent theory of international relations makes geopolitics less predictable and more dangerous. Mr Trump is not a globalist, obviously. Nor is he an isolationist, or a believer in regional spheres of influence. He simply does what he wants, which changes frequently.

One way to make sense of Trumpism is that he divides his efforts at dealmaking into three categories: high, medium and low stakes. In the first category are America’s relations with unfriendly great powers, principally China and Russia. Israel is here, too, because of its importance in American domestic politics. Iran makes an appearance, because of the way it threatens its neighbours. All these relationships are complex, difficult and matter a lot to Mr Trump. If he scores a win here—if he ends the war in Ukraine, or brings peace between Israel and the Palestinians, or finds a formula for co-operating with China without endangering national security—then the pay-off is potentially staggering.

In the medium-stakes category Mr Trump puts Brazil, South Africa and, oddly, giant India. These are important countries that both America and China want in their camp. In most cases, their values are far closer to America’s than to China’s. Ties with them ought to be win-win. But they are unwilling to be bossed around, and take offence when Mr Trump insults or tries to bully them.

The small stakes, for Mr Trump, are in small or poor countries. A superpower can wield great influence over such places, sometimes to good ends. Mr Trump helped cement a peace deal between Azerbaijan and Armenia, for example, and brokered a truce between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. These are welcome achievements. Azerbaijan and Armenia had been fighting for 35 years. Mr Trump mediated a reopening of trade and transport links. The fruits may include a weakening of Russian influence in the area. The Congo-Rwanda deal is much shakier—Rwandan-backed rebels have violated it repeatedly—but not nothing. And there may be an upside for America, in the form of mineral deals.

When it comes to medium-size stakes, Mr Trump’s method works less well. He has started needless feuds with the leaders of Brazil (because it is prosecuting a Trumpy ex-president for allegedly attempting a coup), with South Africa (because he believes, wrongly, that it is persecuting whites) and with India (infuriating its prime minister with painful tariffs and undiplomatic boasting). The result? India will draw closer to Russia again, and be less inclined to act as a counterweight against China. Brazil and South Africa see China as a more reliable partner than America. Mr Trump has won headlines that play well with his most ardent supporters. But America has lost out.

And when it comes to the highest stakes, the president is floundering. He has tried to coerce China with tariffs, but it is fighting back. This week Mr Trump blinked and extended another deadline. He also undermined his own national-security policy by lifting a ban on exports of Nvidia chips to China, while insisting that Uncle Sam gets a 15% cut.

On Ukraine, he has been wildly inconsistent, one day blaming it for having been invaded and threatening to cut military aid, then accusing Mr Putin of bad faith and threatening stiffer sanctions on Russia. On Israel, he has consistently given Binyamin Netanyahu everything he wants and extracted nothing in return. If Mr Trump’s bombing of Iran’s nuclear sites made Israel safer, well and good. But he has failed to use his leverage to restrain Israel’s unending war in Gaza.

The world is flattery

Other countries are learning how to play Mr Trump. A crypto deal and a nomination for a Nobel peace prize worked for Pakistan. A plane helped Qatar. The corruption is turning out to be as bad as almost anyone feared; the great deals have yet to materialise. Those who say Mr Trump is looking out for his own interests, not America’s, have plenty of ammunition.

All this is only a preliminary judgment. If Mr Trump stands up to Mr Putin this week, perhaps he can make his greatest-ever deal, ending Europe’s worst war since 1945. Sadly, the odds are against it. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Want better returns? Forget risk. Focus on fear

A recent study suggests a new paradigm for asset pricing

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Aug 6th 2025|4 min read

An investor will take on more risk only if they expect higher returns in compensation. The idea is a cornerstone of financial theory. Yet look around today and you have to wonder. Risks to growth—whether from fraught geopolitics or vast government borrowing—are becoming ever-more fearsome. Meanwhile, stockmarkets across much of the world are at or within touching distance of record highs. In America and Europe, the extra yield from buying high-risk corporate bonds instead of government debt is close to its narrowest in over a decade. Speculative manias rage around everything from cryptocurrencies and meme stocks to Pokémon cards.

A common explanation for effervescent markets is that investors have become reckless or outright irrational. Or perhaps the relationship between risk and return simply is not there, posits a working paper by Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates, an investment firm, and Edward McQuarrie of Santa Clara University. They argue that over the past two-and-a-bit centuries, risk (as conventionally defined) has done a lousy job of explaining the relative returns of stocks and bonds. In its place, they propose fear—a more complex thing—as the real driving force of markets.

Standard portfolio theory says a stock’s uncertain future returns are distributed along a bell curve. The expected return lies under the peak, and risk is equivalent to the curve’s variance, or spread. These assumptions make the maths elegant and, more important, tractable. But they are also flawed. Stock returns do not in fact follow a bell curve: they take extreme values too often and are asymmetric. Investors, meanwhile, do not regard the curve’s full spread as risky, but just the side of it corresponding to losses. Who, however risk-averse, would be upset by an outsize return?

What is more, risk theory gives an inadequate account of historical returns. A core prediction is the “equity risk premium”, meaning the tendency of stocks, being riskier, to deliver better long-term returns than government bonds. To test this, Mr McQuarrie compiled American stock and bond prices going back to 1793, using data from newspaper archives. Previous studies had seemed to establish the equity risk premium as a persistent, relatively stable property of markets; his new database calls that into question.

An investor who bought American stocks in 1804 would have had to wait 97 years before their return beat that of bonds. By 1933 they would have fallen behind again. A statistical test of the relationship between variance and return, over the database’s full timespan, failed even to find a “modest or inconstant” risk premium. The cumulative equity risk premium (up to 2023) has nevertheless been large. But 70% of it came from an exceptional period between 1950 and 1999; the rest of the time, stocks’ relative performance was middling or poor. And these, after all, were results for one of the world’s best-performing stockmarkets. Other researchers have shown that, since 1900, those of other countries have on average returned far less.

Realised variance and returns contain both expected and unexpected elements, so no theory is likely to match the data perfectly. Even so, the scale of these departures from what risk theory would predict, over such a long timespan, warrants a search for a new framework. Messrs Arnott and McQuarrie propose that instead of pricing assets by their variance, investors price them according to two fears: fear of loss (FOL) and fear of missing out (FOMO). Whereas risk is measured by variance, FOL refers only to its downside (or “semivariance”). An asset inspires FOMO if it has the chance of wild, unexpected gains that those shunning it might miss. This is measured by the “skewness”, or asymmetry, of its return distribution.

Rather than working through fear theory’s maths, which they admit is formidable, the authors hope to tempt others to investigate it with them. They might just succeed. As well as being a widespread, often rational impulse, FOMO helps explain why people would buy overpriced stocks, or even speculative assets with no fundamental source of returns. Its absence from conventional theory seems like an error. And FOL describes how people actually think of risk far better than variance does. Just like investors’ mood and market dynamics, the balance between the two can vary dramatically with time and circumstance. The historical record suggests that portfolio theory needs some new ideas. Fear might be just the thing. ■

Asia | Banyan

Indonesia’s new president has daddy issues

Prabowo Subianto wants to imitate his father. Good luck with that

Illustration: Lan Truong

Aug 14th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

After Prabowo Subianto was elected president of Indonesia last year, he told his younger brother that he would finally be able to “carry out programmes from papi” and fulfil their father’s “aspirations and dreams”. That father is Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, the architect of Indonesia’s post-independence development. He served as a minister under both Sukarno, Indonesia’s first president, and Suharto, the dictator who ruled for 32 years.

But the uncomfortable truth is that if Sumitro were alive today, he would be appalled by the economic populism masquerading as his legacy. The cosmopolitan economist, who founded the economics faculty at the University of Indonesia, would probably see Mr Prabowo’s signature policies—free school lunches, village co-operatives and a new sovereign-wealth fund—as precisely the kind of undisciplined state spending he spent his career warning against.

Sumitro’s economic philosophy wasn’t ideological. Rather, he was pragmatic, believing in rigorous training and evidence. Though he came of age as a socialist in Paris, his approach was grounded in a clear method. First, identify the right problem; second, establish the facts; and only then apply logic to find a solution. When Indonesia lacked trained economists, he persuaded the Ford Foundation to send students to the University of California. That produced the “Berkeley Mafia” of technocrats who would later drive Suharto’s economic success. He argued as early as 1952 that the government should avoid direct economic intervention if there was little capacity to execute it well.

Mr Prabowo’s pledge to spend $28bn a year on free school meals is the kind of sweeping state intervention Sumitro warned against. Indonesian children eat enough, but not well. But instead of nutritional quality, the programme increasingly prioritises raw numbers of meals served, says Arianto Patunru of Australian National University. The best way to reduce stunting is to help pregnant women and toddlers; the current policy misdirects resources to schoolchildren.

Or consider the example of co-operatives. Sumitro supported them as tools for genuine, decentralised development, not as instruments of political control. This perspective had deep roots. In 1942 he completed his PhD thesis on rural credit in Java while he was living in the Netherlands, which was occupied by Germany at the time. For the rest of his career this research fuelled his belief that small traders throughout Indonesia would remain trapped in poverty unless the government invested in education, training and co-operatives.

This spirit of grassroots empowerment could not be more different from Mr Prabowo’s latest initiative of “red-white co-operatives”. Unveiled in July, the programme imposes a uniform model on 80,000 co-operatives nationwide, requiring each to run the same services regardless of local needs, says Kevin O’Rourke, a political analyst. This betrays the spirit of genuine co-operatives. The policy is designed to extend central control into rural areas, rewarding loyal village heads.

The most glaring case of historical revisionism is Danantara, Indonesia’s new $900bn sovereign-wealth fund. Mr Prabowo’s brother, Hashim Djojohadikusumo, has said that it fulfils their father’s vision of consolidating state assets and directing strategic investment. But Sumitro might well have thought its structure was a mess. Danantara reports directly to the president, is chaired by Mr Prabowo’s former campaign manager and has little oversight. Sumitro would have recognised this as a textbook case of what he called Indonesia’s “institutional disease”: the corrosion of public policy by vested interests. He diagnosed this problem at the height of the Asian financial crisis in 1998, when Suharto was bending state power to serve his family’s businesses. This week the head of a state-owned farming firm quit six months into the job, blaming Danantara for needless red tape.

Sumitro understood that a developing economy faces a delicate balancing act. His policies aimed to attract foreign investment while steadily building Indonesia’s institutional capacity. His son, by contrast, has chosen to trade fiscal stability for flashy, vote-winning programmes that entrench his power and do little to drive long-term growth. His administration blends authoritarian control with populist spending. This is a travesty of Sumitro’s real legacy: of the disciplined fiscal policy and strong institutions Indonesia badly needs. ■

Asia | Nepo politics

What Sara Duterte’s comeback means for the Philippines

She could be the front-runner for the election in 2028

Photograph: Getty Images

Aug 14th 2025|MANILA|2 min read

Listen to this story

AFEW months ago, things looked grim for Sara Duterte, the vice-president of the Philippines. The country’s House of Representatives had impeached her, accusing Ms Duterte of misusing public money and threatening to assassinate the president, Ferdinand “BongBong” Marcos. She faced a ban from politics if convicted of the charges in a trial in the Senate. Then the International Criminal Court indicted her father, Rodrigo, for crimes against humanity committed in a brutal drug war during his presidency (he denies this). The Duterte dynasty looked like it was over.

Yet the family now seems on the up. The Supreme Court struck down the impeachment complaints against Ms Duterte in late July. A couple of weeks later the Senate voted not to proceed with a trial for now. These wins make Ms Duterte likely to be the front-runner to be the Philippines’ next president, in 2028. It also means that over the next three years her nasty feud with Mr Marcos, also a scion of a political clan with a grubby history, will become even more disruptive for the country.

Ms Duterte typifies the Philippines’ dynastic political system, where powerful families make up around 80% of Congress, one of the highest shares in the world. She first took office in 2007 as vice-mayor of Davao, a city where her father was elected mayor eight times. The family name helped her win the vice-presidency in the 2022 election, during which she formed an uneasy partnership with Mr Marcos.

She also thrives in a political culture dominated by big personalities. Celebrities are often elected in the Philippines, and politicians play up to the crowds on social media and in real life. At a recent election rally in Manila, the capital, the mood felt more like a rock concert, with her supporters wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Bring Him [Rodrigo] Home” (from The Hague).

Her views appear to be similar to her father’s. She has criticised Mr Marcos for tilting towards America and said that the Philippines “shouldn’t lean toward any foreign power”. Still, it is not clear whether and how far she would, or could, reorient the country towards China, which her father cosied up to. Ties with America are stronger now than in 2016, when Mr Duterte took office. In late July Mr Marcos secured a trade deal with America. Philippine exports face a tariff of 19%. This is only one percentage point lower than Donald Trump’s threat before the agreement, but Mr Marcos still billed it as a win.

Yet with the Dutertes resurgent—for now at least—the dynastic dispute could disrupt the second half of Mr Marcos’s presidency. Ms Duterte has a growing number of allies in Congress. They may try to obstruct Mr Marcos, who cannot run again because of term limits. As a result, he could become a lame duck if enough politicians rally behind her. ■

China | Working mothers

China claims to want women to have children and a career

But special “mum jobs” are hardly helping

Illustration: Anna Kövecses

Aug 14th 2025|Beijing|3 min read

Listen to this story

WHEN MS WANG returned to work at a Chinese internet giant after having a baby, her boss pulled her aside. She told her she’d be less invested in her work because the country’s breastfeeding policy would allow her to leave one hour earlier. “I’ll be a normal colleague, not a breastfeeding mother,” she replied, staying past 10pm regularly like the rest. Based in Beijing, she was entitled legally to 158 days of maternity leave. But she received the worst performance rating in her team last year because others had to cover her work while she was away. She was fired in April.

Meanwhile, the government is trying desperately to boost China’s birth rate. On July 28th it announced that it would give households 3,600 yuan ($500) a year for each child under the age of three. Economists estimate the subsidy will cost the state about 100bn yuan a year, or about 0.07% of the country’s GDP. And it promotes “mum jobs”, which offer mothers with children under the age of 12 more flexible work schedules. In recent months Hubei province launched one of the first province-wide schemes to provide them.

Mum jobs were first introduced in 2022, when China’s National Health Commission issued guidelines for supporting childbearing. Increasingly local governments encourage firms to create them as part of a national campaign for “a birth-friendly society”. By the end of last year, Guangzhou had listed 12,760 mum jobs in e-commerce, housekeeping, manufacturing and other sectors. Chongqing has tallied more than 23,000.

But most of the time such jobs are menial, low-paid and hourly. Peng Yingbin, for example, offers flexible schedules for between 30 and 50 mothers who work at his clothing factory in the poor province of Guizhou. Paid per piece completed, his staff—most of whom moved to town with their children for better schooling—can leave earlier for school pickups.

As the number of mum jobs grows, so does the backlash against them. “In a gender-unequal society, this appears to offer mothers job opportunities, but it actually offers them low-paid gig work,” wrote one online commenter. Hubei’s new mum jobs scheme has raised a furore. “Why are there no dad jobs?” many asked. (Shanghai got around this objection by introducing “birth-friendly jobs” in 2024.)

On top of it all, the state also wants women to work as China’s population ages. Liu Shenglong of Tsinghua University in Beijing, points out that nearly 60% of current undergraduates are women. “If we were to remove these people from the labour market, wouldn’t that be a huge waste?” Most mothers also want employment. About four in five stay-at-home mums in China want to re-enter the workforce, and about two in five of them are interested in part-time or flexible roles, according to a survey conducted by the All-China Women’s Federation in 2023.

While hunting for new positions, the mum jobs Ms Wang comes across are basic administrative roles that don’t appeal to her. “They’re taking women who are already marginalised in the workplace and pushing them even further into marginal positions,” she says. Instead she hopes for changes to workplace culture and greater corporate accountability. Officials should note such pregnant ideas. ■

United States | Lexington

The real collusion between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin

It may be scarier than their critics long suspected

Illustration: David Simonds

Aug 14th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

To thwart Donald Trump is to court punishment. A rival politician can expect an investigation, an aggravating network may face a lawsuit, a left-leaning university can bid farewell to its public grants, a scrupulous civil servant can count on a pink slip and an independent-minded foreign government, however determined an adversary or stalwart an ally, invites tariffs. Perceived antagonists should also brace for a hail of insults, a lesson in public humiliation to potential transgressors.

Vladimir Putin has been a mysterious exception. Mr Trump has blamed his travails over Russia’s interference in the 2016 election on just about everyone but him. He has blamed the war in Ukraine on former President Joe Biden, for supposedly inviting it through weakness, and on the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, for somehow starting it. Back when Russia invaded in February 2022, Mr Trump praised Mr Putin’s “savvy”.

For months, as Mr Putin made a mockery of Mr Trump’s promises to end the war in a day and of his calls for a ceasefire, the president who once threatened “fire and fury” against North Korea and tariffs as high as 245% against China indulged in no such bluster. He has sounded less formidable than plaintive. “Vladimir, STOP!” he wrote on social media in April. His use of the given name betrayed a touching faith that their shared intimacy would matter to his reptilian counterpart, too.

When Mr Putin kept killing Ukrainians, Mr Trump took a step that was even less characteristic: he admitted to the world that he had been played for a fool. “Maybe he doesn’t want to stop the war, he’s just tapping me along,” he mused on April 26th. A month later, he ventured that his friend must have changed, gone “absolutely CRAZY!” Then on July 8th he acknowledged what should have been obvious from the start: “He is very nice all the time, but it turns out to be meaningless.” Mr Trump threatened secondary sanctions on Russia but then leapt at Mr Putin’s latest mixed messages about peace, rewarding him with a summit in America.

Why, with this man, has Mr Trump been so accommodating? Efforts by journalists, congressional investigators and prosecutors to pinpoint the reason have often proved exercises in self-defeat and sorrow. The pattern seemed sinister: Mr Trump praised Mr Putin on television as far back as 2007; invited him to the Miss Universe Pageant in Moscow in 2013 and wondered on Twitter if he would be his “new best friend”; sought his help to build a tower in Moscow from 2013 to 2016; and tried unsuccessfully many times in 2015 to secure a meeting with him. Then came Russia’s interference in the election in 2016, including its hack of Democrats’ emails to undermine the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton. Some journalists fanned suspicions of a conspiracy—“collusion” became the watchword—by spreading claims Mr Putin was blackmailing Mr Trump with an obscene videotape. The source proved to be a rumour compiled in research to help Mrs Clinton.

Nine years later Mr Putin’s low-budget meddling still rewards America’s foes by poisoning its politics and distracting its leaders. Pam Bondi, the attorney-general, has started a grand-jury investigation into what Mr Trump called treason by Barack Obama and others in his administration. The basis is a misrepresentation of an intelligence finding in the waning days of Mr Obama’s presidency. Tulsi Gabbard, the Director of National Intelligence, has said that because Mr Putin did not hack voting machines, the finding that he tried to help Mr Trump was a lie. The conclusion under Mr Obama was instead that Mr Putin tried to affect the election by influencing public opinion.

The exhaustive report released in 2019 by an independent counsel, Robert Mueller, affirmed on its first page that “the Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome.” Mr Mueller indicted numerous Russians, and he also secured guilty pleas from some Trump aides for violating various laws. But he did not conclude the campaign “conspired or co-ordinated” with the Russians.

To wade through the report’s two volumes is to be reminded how malicious the Russians were and how shambolic Mr Trump’s campaign was. It is also to lament the time and energy spent, given how little proof was found to support the superheated suspicions. And it is to regret how little Mr Trump was accorded a presumption of innocence. In the final words of the report, Mr Mueller noted that while it did not accuse Mr Trump of a crime, it also did “not exonerate him”. One might understand his bitterness.

The puzzle of Mr Trump’s admiration for Mr Putin may have been better addressed by psychologists. Certainly Mr Putin, the seasoned KGB operative, has known how to play to his vulnerabilities, including vanity. Mr Trump was said to be “clearly touched” by a kitschy portrait of himself Mr Putin gave him in March.

Putin on the blitz

Yet that patronising speculation may be unfair to Mr Trump, too. It certainly understates the hazard. He has weighty reasons to identify with Mr Putin. Since the 1930s a cornerstone of American foreign policy has been that no country can gain territory by force, a principle also enshrined in the charter of the United Nations. Yet in his first term, in pursuit of his vision of Middle East peace, Mr Trump twice granted American recognition of conquered territory, for Israel’s claim to the Golan Heights and Morocco’s claim to Western Sahara. He appears to envisage an end to the war in Ukraine that would also award Russia new territory.

This is how “savvy” people like Mr Trump and Mr Putin believe the world actually works, or ought to: not according to rules confected by stripy-pants diplomats to preserve an international order, but in deference to power exercised by great men. A world hostage to that theory may be the legacy of their true collusion. ■

The Americas | Ever-present Evo

Bolivia’s crazy kingdom of coca

Former leader Evo Morales is hiding out there

Photograph: Reuters

Aug 14th 2025|Chapare|5 min read

Listen to this story

After a few drinks, Feliciano Mamani hoicks up his trouser leg to show where the police shot him 30 years ago, when he was a young coca farmer resisting the government’s eradication programme, leaving a purplish crater in his leg. Yet when he recounts the two times he came even closer to death, this wound barely makes the cut.

Map: The Economist

War stories abound in the Chapare, Bolivia’s coca kingdom. It has been peaceful since Evo Morales emerged from its coca farmers’ union to lead the Movement to Socialism (MAS) to power in 2006. But that may soon change. Torn into factions, the MAS looks set to lose the coming election. Mr Morales was forced out of the MAS and is now in the Chapare evading arrest for alleged statutory rape. He says the charge is politically motivated and wants supporters to spoil their ballots to protest his exclusion from the poll by a court ruling. His future hangs in the balance. So do the prospects for the Chapare—and for Bolivia.

The split in the MAS goes back to 2019, when Mr Morales resigned after a disputed election in which he sought an unconstitutional third consecutive term in office. He went into exile, only to return when Luis Arce, his former finance minister, retook the presidency in 2020. Mr Morales wanted another run at the top post. But it soon became clear Mr Arce wanted to keep it.

After years of infighting, neither man has got onto the ballot this time. An economic crisis, with fuel shortages and inflation likely to hit 30% this year, ruined Mr Arce’s electoral chances, so he withdrew. Mr Morales’s candidacy was blocked by a court ruling on term limits. In the process the MAS’s reputation was wrecked.

The election Bolivia faces on August 17th is its most unpredictable in 20 years. The front-runners are Samuel Doria Medina, a centrist tycoon, and Jorge Quiroga, a right-wing former president. Pollsters reckon neither will surpass 25% in a field of eight; a run-off in October is likely. The left’s only real hope is Andrónico Rodríguez, 36, the Senate’s president, who is running not for the MAS but for the People’s Alliance. Though he is polling at under 10%, the rural vote has strongly favoured the MAS and is often undercounted in polls: it could yet back him.

But Mr Morales stands in the way. Mr Rodríguez is part of the same coca farmers’ union and was considered his political heir. Now Mr Morales calls him a traitor and wants Bolivians to spoil their ballots. His plan is to delegitimise the poll, then lead a resistance from the Chapare again.

The road to the Chapare winds from arid highlands into tropical forest. About 260,000 people, many descended from internal migrants escaping drought and poverty, live there across five coca-growing municipalities. The newcomers turned to coca, which grows easily and can yield four harvests a year. There is a market for leaves that Andeans have chewed as a stimulant for millennia. But in the 1980s demand for coca to produce cocaine exploded.

Coca farmers say the union was forged in the repression that ensued. When forced eradication backed by the United States began, farmers fought back. Eventually they won the right for each union member to have a coca plot of 1,600 square metres. With Mr Morales as president, the unions took responsibility for stopping illegal production over the allotted limit.

Almost 50,000 coca farmers belong to an overarching body known as the Six Federations, still led by Mr Morales. They pay dues, take part in meetings and, if called upon, take to the streets. Now they also take turns protecting Mr Morales in the village of Lauca Eñe, where hundreds of people with sharp staves have formed a ragtag garrison ever since police fired on his car last October. Mr Morales accuses the government of trying to kill him; officials say his vehicle rammed through a checkpoint.

The Six Federations unofficially reigns over the Chapare and the five coca municipalities. It runs the coca trade, controls prices and taxes the proceeds. It controls much else, from land tenure to low-level justice. Its own media pump out propaganda. Mr Mamani, who was a mayor in the Chapare for ten years, says the union wants to have an international TV channel.

Under Mr Morales’s presidency the region flourished. Villa Tunari, the biggest municipality’s hub, now has hotels, gyms and karaoke. Coca farmers plant tropical fruits and dig ponds to farm tambaqui, a tasty fish. The price of land has rocketed. A hectare by the main road that cost $300 or so in the 1990s, says a coca farmer, now goes for $10,000. Many farmers also own property in the city of Cochabamba, where their kids go to university.

Not all this prosperity is legal in origin. Mr Morales kicked the US Drug Enforcement Administration out in 2008. Much of the region’s coca feeds the drug trade; many of its hotels and tourist ventures are said to be money-laundries.

But things have soured since Mr Morales left power. Public money no longer flows to the region. Drug labs have more often been busted. And the mood could worsen still after the election. Mr Morales’s loyalists are sure most Bolivians will spoil their ballots, though polls suggest no more than 15% of Bolivians overall plan to. But even 20% would be startling.

A shot in the foot

In any case, a big null vote makes the current opposition more likely to win. And Messrs Doria Medina and Quiroga have both said Mr Morales will go to prison if either of them is elected. “Evo would be a trophy,” says Iván Canelas, ex-governor of Cochabamba and a friend of Mr Morales. “They could kill ten people and grab Evo and lots of people in the city will say it’s what had to be done.”

The Six Federations is preparing to resist. María Eugenia Ledezma, its top female leader until a few months ago, says they will use guerrilla tactics against soldiers who venture into the Chapare, depriving them of sleep, then attacking with sticks and stones. She says miners have been teaching people how to make boobytraps with dynamite; sympathisers in the army have been training the young. “Many of us, many leaders, will surely die or be imprisoned,” she says, grim-faced. ■

The Americas | Assisted death

Liberal Uruguay and the right to die

Could its approach spread across Latin America?

Illustration: Xiao Hua Yang

Aug 14th 2025|Montevideo|6 min read

Listen to this story

Pablo Cánepa was a normal, healthy 35-year-old Uruguayan. Handsome and extroverted, he was a talented graphic designer who loved to host barbecues with his girlfriend and was fanatical about Nacional, a local football team. Taking a shower in March 2022, he suddenly felt dizzy. He thought little of it.

But within four months he was trapped in his own body; his brain had lost almost all control of his muscles. As a kid, he loved to draw. Now he cannot sit, feed himself or control his bladder and bowels, let alone hold a pencil. His 75-year-old mother must change his sodden nappies. His mind is lucid. He knows exactly what has happened—what he has lost—but even his eyes do not work; he sees double. Speaking is exhausting. For three years he has been lying staring at the ceiling, unable to move his limbs to relieve the stiffness and pain, his muscles withering. Trapped, he suffers panic attacks. He has been denied even a clear diagnosis. All the doctors can tell him with certainty is that he has irreversible brain damage with no known cause. Pablo wants to die. He has said so repeatedly since early 2023. But under Uruguayan law no one can help him to do so.

That could soon change. On August 13th Uruguay’s lower house passed a law with a thumping majority to legalise assisted dying. The Senate, where a similar bill got stuck in 2022, is widely expected this time to follow suit. Legal assisted dying would continue Uruguay’s long liberal tradition and put it among a handful of countries in the world to have legal marijuana, gay marriage and assisted dying. For Pablo, the law cannot come soon enough.

In Colombia and Ecuador assisted dying was decriminalised after court battles. Cuba recently declared it legal, too. None of these countries has a comprehensive law to regulate it, so its application is often very limited. Colombia is the most advanced but even there it is bafflingly complicated. Uruguay would be the first country in Latin America to pass a comprehensive law legalising assisted dying that would make it widely available. Advocates in Chile, where an assisted-dying bill is stuck in the Senate, are watching closely.

The law that Uruguay’s lower house passed is strikingly liberal, more so than a current effort in Britain, where assisted dying would be limited to those with a terminal illness who will anyway die within six months. Uruguay’s bill imposes no such time limits. Moreover, it is open to people with an incurable illness that generates unbearable suffering, even if it is not terminal. That applies crucially to Pablo, whose disease is torture but not terminal.

Uruguay’s bill still has constraints. Mental conditions such as depression are not explicitly ruled out but patients need at least two doctors to determine that they are psychologically fit to make the choice. Minors are excluded. So are directives whereby people who are in good health can leave instructions to be helped to die in the future, should they become so ill that they are unable to communicate.

Opposition to the law comes chiefly from the religious. Daniel Sturla, the archbishop of Montevideo, the capital, worries that, together with legal abortion, assisted dying is creating a “culture of death”. He warns of “a mindset where life is disposable and where there are lives worth living and lives not worth living”. Some argue that palliative care renders assisted dying unnecessary by reducing patients’ suffering as they near the end. Others add that palliative sedation, which some doctors in Uruguay apply to relieve suffering and, in effect, to marginally hasten death at the very last moments, already does enough.

We shouldn’t have to wait

The frustration of the Cánepa family with such objections is palpable. Pablo’s brother Eduardo lists a slew of Uruguayan organisations and politicians campaigning against the law. “They claim to be empathetic toward life…but it is only in the abstract,” he says, his voice cracking with emotion. “None of them has called us, none of them has sent us a message to see if we need something, to see if they can help—absolutely nothing.”

Palliative care is more widely available in Uruguay than in most of Latin America. But for Pablo in practice it means two visits of perhaps 30 minutes a week, even though he has both state help and private insurance. Palliative care is undoubtedly necessary, but is not a substitute for assisted dying, argues his brother Eduardo. Indeed in Canada, he notes, the vast majority of people who choose an assisted death also receive palliative care.

Florencia Salgueiro, a leading campaigner for assisted dying in Uruguay, has first-hand experience of the limits of palliative sedation. Her grandfather and uncle died of a neurodegenerative disease. Then it got her father, who died aged 57 in 2020 after a torturous last few months. Doctors obediently followed the law, apologetically rebuffing his requests to be helped to die sooner through palliative sedation.

Pollsters reckon some two-thirds of Uruguayans favour legalising assisted dying. Remarkably, a solid majority of Uruguay’s Catholics back it, too. “Uruguayan Catholics are different from Argentine Catholics or Brazilian Catholics,” says Archbishop Sturla. “Secularisation [in Uruguay] has reached the soul, the culture,” he laments. Indeed every country in Latin America except Uruguay has a majority who say they are Christian.

Uruguay’s support for assisted dying is built on a strikingly secular and liberal tradition that is unique in the region and was promoted by early political leaders. Back in 1877 they declared state schools to be free, obligatory and secular. That was five years before France, the exemplar of secular education. Uruguay’s constitution of 1918 explicitly separated church from state. Unlike in many countries, it is strictly followed. Easter is officially (and widely) called “Tourism Week”. Christmas is “Family Day”. The Argentine constitution, by contrast, still says the government must “support” Roman Catholicism.

Liberalism in Uruguay runs just as deep. In 1907 it was the first country in Latin America to fully legalise divorce, some 97 years before nearby Chile. More recently, in 2012, it was one of South America’s first countries to fully legalise abortion. In 2013 it was the second to legalise same-sex marriage. In the same year it was the first country in the world to legalise marijuana.

History and public opinion may favour the Cánepas but they remain cautious. “I want to see it approved before I believe,” says Eduardo. How will he feel if it is? “Relieved,” he replies. “I don’t want people to die. I want people to be able to choose.” ■

Middle East & Africa | The war in Gaza

The world’s hardest makeover: Hamas

Dissent against it builds inside and outside the strip

Photograph: AFP

Aug 14th 2025|CAIRO AND ISTANBUL|5 min read

Listen to this story

It was born as the Islamic Resistance Movement. It is more usually known by its Arabic acronym, Hamas. But talks taking place in Cairo could determine whether the Palestinian militants drop the middle word, abandon their 22-month war in Gaza against Israel and reinvent themselves as a political party.

On August 12th Khalil al-Hayya, the head of Hamas’s Gazan wing, arrived in Cairo for negotiations mediated by Egypt with Qatar and Turkey. On the table is a proposal to decommission its weapons, dissolve its armed brigades, free the remaining hostages and surrender power. In exchange, Israel would withdraw from Gaza, an interim Palestinian technocratic administration would be put in place supported by a un-endorsed international force and the rebuilding of the devastated territory would begin.

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

The external pressure on Mr Hayya to accept such a deal is intense. Binyamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, is threatening to occupy the whole of Gaza. On August 12th Israeli forces began heavy strikes on Gaza city. Another offensive could destroy what remains of Hamas there and hasten the ethnic cleansing of the entire strip. The weakening of Iran has stripped the group’s armed wing, the Ezzedin al-Qassam Brigades, of its main foreign backer. Hamas’s last regional backers, Qatar and Turkey, have long favoured the group’s political arm. But they seem to be losing patience. They are understood to have said that if Mr Hayya refuses a deal, they might refuse to allow him and Hamas’s other leaders, who all left Doha a fortnight ago, to return.

Hamas faces even more pressure from those on whose behalf it claims to fight. The movement was born in Gaza. But the population that propelled it to victory in elections two decades ago has turned on the group. Few see value in a resistance that invites devastation upon them. While its fighters shelter in tunnels and its politicians negotiate over the width of a buffer zone, around a hundred Gazans were killed each day in July, nearly all by Israel. Threats of reprisals no longer mute criticism. “People in Gaza are furious with Hamas,” says a journalist from Gaza now in exile in Qatar. “They just want the nightmare to end.” A political activist in Gaza blames Hamas for the famine.

“Hamas’s insistence on keeping power gives Israel the pretext to starve us,” he says. “Hamas should dissolve and disappear.” Dissent is even spilling through Hamas’s ranks. On WhatsApp groups, some members are calling for a laying down of arms before Gaza suffers even more.

Others in Hamas envision the group becoming a political party, in the manner of Northern Ireland’s Sinn Fein or Israel’s own legal Islamist party, the United Arab List.

Justice and Development, one suggests calling it.

Reimagined, it could agree to the conditions set by the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, for participation in recently announced Palestinian elections. They include endorsing a two-state settlement, negotiations with Israel and Mr Abbas’s demand for a monopoly on Palestinian weapons. Given the disenchantment with Fatah, his own lacklustre movement, and the admiration Hamas’s grit still attracts outside Gaza, they might even win. “It’s been months since I’ve been this optimistic,” says an adviser to the movement exiled from Gaza.

And yet in Gaza city the Brigades fight on. Apart from cobbling shoes out of wood and rubber, it is one of the last job opportunities Gaza still offers. Israel’s attacks may have decimated Hamas’s ranks, but they still have weapons to harry their foe. Their presence spared Gaza even worse atrocities, they say, implausibly. “Without the Qassam Brigades we’d have had hundreds of Sabras and Shatilas,” argues the exiled son of a slain military commander, referring to the slaughter of thousands of Palestinian refugees in Israeli-occupied Beirut in 1982. Many still think they could regain power in Gaza. Asked to describe the Qassam Brigades’ mood, a Palestinian interlocutor with Hamas adopts an Irish lilt. “No surrender,” he says.

Meanwhile in exile, Hamas’s leaders reckon that Israel may be winning the battles but is losing the war. As in Algeria’s war of independence, their reading is that the resistance has turned the enemy’s weapons against itself, exhausting the Israelis and draining them of their international legitimacy and moral authority. Far from ending the conflict, they argue, a mass exodus of Palestinians from Gaza would intensify it. Algeria won independence only after a million Algerians had lost their lives. “Be patient, Gaza,” says Ghazi Hamad, a senior member of Hamas.

How can Hamas be pushed to accept a deal? A commitment, if given, by a new Arab committee overseeing its implementation to integrate tens of thousands of Hamas’s civil servants into a new Palestinian administration and perhaps some fighters into the security forces might help. Hamas’s political leaders have expressed readiness to hand over their weapons to a new Palestinian administration in Gaza, once Israel fully withdraws. “The Brigades will accept the movement’s decision,” says a strategist close to Hamas in Istanbul.

But many obstacles remain. America and Israel must also accept the terms, and neither has come to Cairo. Despite the rising costs for Israel, Mr Netanyahu still prefers military to diplomatic endgames. The details of Hamas’s disarmament, any international force and an interim technocratic Palestinian government have yet to be determined, says an Egyptian observer. And Hamas’s “pragmatism” has only ever gone so far. In 1991, after the end of the first Palestinian intifada (uprising), and the start of direct Israeli-Palestinian talks, one of Hamas’s founders declared mission accomplished. He proposed disbanding Hamas’s armed wing and joining the negotiations. How can we forgo our brand recognition, retorted his brothers? Too many within Hamas may still feel the same. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Must Europe choose between “strategic autonomy” and August off?

A continent on holiday from geopolitical reality

Photograph: Peter Schrank

Aug 14th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Europeans and Americans concur: there is something fishy about a two-week summer holiday. But the rationale for their concerns is markedly different. To Wall Street and Silicon Valley types, indulging in an uninterrupted fortnight of vacation—a whole fortnight!—means essentially throwing in the towel. Imagine what opportunities for promotion will be forsaken by bunking off for 14 straight days. To office toilers in Stockholm, Rome or Paris, two weeks of leave seems equally suspect. Seulement two weeks? That would be acceptable only as the opening act of a proper summer break. Ideally this should stretch to a whole month. How else to recover from the existential drudgery of work? American out-of-office emails beseech the sender to wait a few hours while the holidaying recipient snaps out of beach mode to respond to their message (sorry!). European out-of-office messages politely invite the sender to wait until September (not sorry).

Europe quietly revels in being a lifestyle superpower, with better food and longer life expectancy than America. But it is also an anxious place these days. The two months since June 21st—the traditional start of the Scandinavian holiday season—will go down as a summer of geopolitical subservience. At a NATO summit in June, a parade of European leaders toadied to Donald Trump; the alliance’s (Dutch) boss elicited cringes by praising him as the group’s “Daddy”. A summit marking the 50th anniversary of the European Union’s diplomatic ties to China in July was shifted to Beijing after President Xi Jinping made clear he had no intention of travelling to Brussels. The killing in Gaza goes on, even as European leaders protest. They have also had to swallow Trumpian edicts on trade, meekly agreeing not to reciprocate even while their exports to America get walloped with tariffs. On August 15th Mr Trump will host his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, in Alaska to discuss Ukraine. For France, Germany and other Europeans, the war is the ultimate threat to their continent’s security, yet they will not get a seat at the table.

The Alaska confab is a sharp reminder to Europeans that they live in a world where others increasingly call the shots. The idea that the continent needs to recover some measure of “strategic autonomy” was once a French obsession. Now it is widely shared. But shaping one’s own future—spending more on defence, producing more stuff instead of importing it, and so on—looks a lot like hard work. Shorter summer holidays by themselves will not rid Europe of its dependencies on China and America. But Europe’s geopolitical irrelevance is in no small part down its somnolent economy. There, working habits do matter. Whereas productivity gains in America and China have in recent decades translated into higher GDP, and in turn geopolitical heft, in Europe those advances have been used to toil less instead.

Though not exactly an indolent continent, Europe prides itself on indulging in la dolce vita. Not feeling tip-top as you head to the beach? Fret not: under EU law employees can suspend their holidays if they are unwell, ensuring that any sick days translate into more holidays later. Taken as a whole, Europeans work fewer hours in the week than most others globally, either because of legal restrictions or thanks to a penchant for part-time work (nearly a third of Europeans work fewer than 35 hours a week, a world record). They then work fewer weeks in the year, thanks not just to long holidays but to parental leave—as much as 480 days, for Swedish mums and dads. The average German now takes 15 days of sick leave every year, too. And to top it all off, Europeans work fewer years in their career, despite long life expectancies. The average Frenchman spends 23 years in retirement, over half a decade more than his Japanese or American counterparts.

E allora? some might say. By forsaking the office or factory floor Europeans are in effect purchasing leisure, rather than putting in extra hours to buy yet more stuff. Who is to say an inflated pay slip is worth more than time spent eating and playing? Yet increasingly, it feels like the extra cash would come in handy. Europe’s public finances are ever more stretched. Hefty defence commitments agreed in June are framed as a tussle of “warfare v welfare”, as if governments can only spend on defence by cutting pensions. But Europe might not need to choose between guns and butter: by working more it might be able to afford both. The focus in the continent’s economics ministries has been to improve productivity. Fostering innovation and cutting red tape are indeed needed to squeeze more output for every hour of labour. But while working better matters, what about working more?

Working nine to three

Friedrich Merz, the German chancellor, has warned that “work-life balance” and four-day weeks stand in the way of national prosperity. He is right. Happily for holidaymakers in Berlin and beyond, little is likely to change soon. While “strategic autonomy” sounds nice to those voters who can make sense of it, more time at the beach sounds even better. Politicians who have goaded their compatriots to put in an extra shift—Nicolas Sarkozy, a former French president, suggested people “work more to earn more”—have been rewarded with early retirement. A plan to cut two national holidays in France to help public finances has been greeted with the kind of enthusiasm reserved for August storms.

There is nothing reprehensible about wanting to work to live rather than live to work. Alas, the laws of geopolitics, unlike most European labour codes, do not offer five weeks of holiday. Put simply: more working means more money, and more money means added clout in global affairs. Until the 1960s Europeans toiled longer hours than Americans, and mattered somewhat more in the world. That is no coincidence. If Europeans want a seat at the global geopolitical table, they will have to work for it.■

International | Rumble in the jungle

America’s new plan to fight a war with China

Readying for a rumble in the jungle

Photograph: U.S. Air Force

Aug 14th 2025|TINIAN AND GUAM|8 min read

Listen to this story

IT COULD BE a giant archaeological dig. Bulldozers tear at the jungle to reclaim the history of the second world war and its dark finale: the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago this month. The work on Tinian, a speck in the Pacific Ocean, has exposed the four runways of North Field. Glass protects the cement pits where Little Boy and Fat Man, the first and only atom bombs used in war, were loaded onto American B-29s. For a time Tinian was the largest air base in the world, but it was soon mostly abandoned.

With China as its new rival, America is reviving old wartime facilities across the Pacific. Tinian once allowed its bombers to smash Japanese cities. These days China wields the long spear: it has built up a vast stockpile of missiles that can blast American bases in the region. Any war between the superpowers would be a cataclysm. And both now have nuclear weapons.

As in the cold war, nuclear worries go hand in hand with preparations for conventional conflict. The air force is expanding Tinian’s small commercial airport as a backup landing place. On the day your correspondent visited, two F-22 jets—America’s most capable fighters—took off with a deafening roar. Crews huddled in tents as C-130 transporters brought gear.

Photograph: U.S. Air Force

The fighters had deployed from Alaska for the recently concluded REFORPAC exercise—part of the biggest air-force war game in the Pacific since the cold war—involving more than 400 aircraft and 50 locations thousands of miles apart. It demonstrated America’s ability to bring forces quickly from the American mainland. It was also a test of “Agile Combat Employment” (ACE), a doctrine of hide-and-seek whereby American aircraft disperse to small bases to survive attacks by China, rejoin in the air to punch back and then scatter again—like a murmuration of starlings.

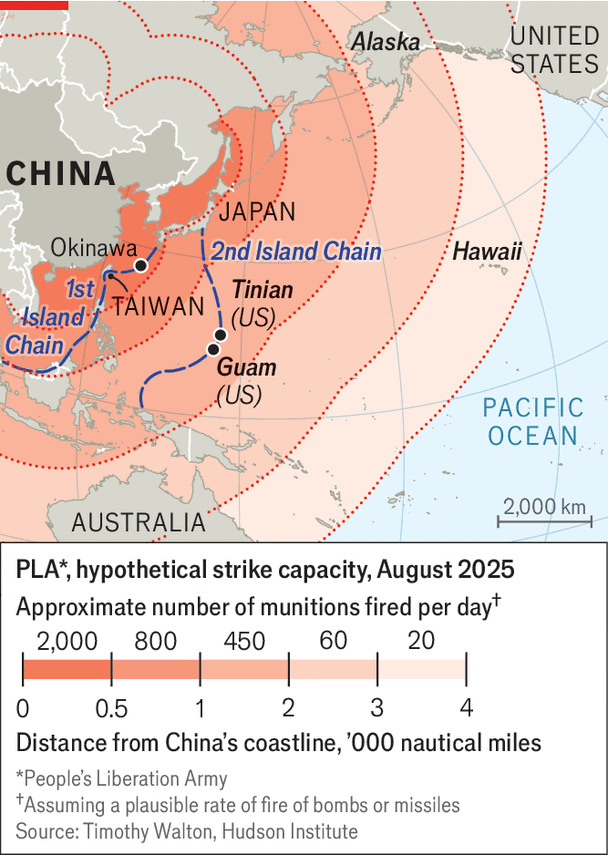

Map: The Economist

Because of China’s reach, the air force can no longer mass its planes in big bases close to the action, as it has done in recent decades. It must plan to survive and fight throughout China’s deep “kill zone”, learning from the island-hopping campaigns of the Pacific war and more recent conflicts. Ukraine has shown how, even under relentless attack, its planes can keep fighting by hiding and moving. America intends to do the same on a grand scale. “In a peer conflict our airmen will be under constant threat,” explains General David Allvin, the chief of the air force. “We must be lethal and agile, aggregating for effect and disaggregating for survival.”

Even so, it faces formidable difficulties, including the vastness of the Pacific; the density of China’s firepower; the paucity of usable airfields; the shortage of bomb-proof hangars; the vulnerability of air-refuelling tankers; the complexity of logistics; and the disruption of data networks.

China would be fighting mostly in its backyard, within the “first island chain” that runs from Japan to Malaysia—with Taiwan, about 100 miles away, at its heart (see map). Most American forces would be rushing in from the far side of the vast ocean, thousands of miles away. Many of China’s ballistic missiles have a greater range than the usual combat radius of America’s fighter jets (typically 500-600 nautical miles, or nm).

Photograph: U.S. Air Force

Calculations for The Economist by Timothy Walton of the Hudson Institute, an American think-tank, illustrate the challenge. His model suggests China could rain about 2,000 bombs or missiles a day on targets within 500nm, including hundreds on Kadena, a big American air-force base in Okinawa. It could simultaneously drop some 450 munitions a day over the second island chain, including Guam and its vital complex of bases, 1,600nm away; 60-odd over important rear bases in Alaska; and perhaps a score a day over faraway places such as Hawaii, the headquarters of America’s Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), 3,600nm back. Missiles can strike quickly and accurately, though most munitions would in fact be delivered by aircraft. (These theoretical figures assume that no planes or missiles are shot down, and Chinese facilities are not attacked.)

Ride into the danger zone

There are relatively few good landing spots east of the first island chain before reaching the continental United States. Mr Walton counts just 21 in American and allied territories with the runways, aprons and fuel supplies to take tankers, bombers and larger aircraft. Smaller fighter jets could use up to 125 airfields, but most are farther from China than their usual range, even with air-to-air refuelling. All this assumes host countries would grant permission for “ABO”—access, basing and overflight—and risk China’s wrath.

Aircraft-carriers, which helped win the Pacific war and have symbolised American power ever since, are increasingly vulnerable to China’s long-range “carrier-killer” missiles, such as the DF-26B with a range of more than 2,000nm. Unlike carriers, which may sink when struck, airfields can be repaired, often within hours.

Thus the importance of Tinian. Its four new runways, once refurbished, will provide valuable alternatives to the two at Andersen air base on Guam, and two more that have been refurbished nearby. The air force, which says it just needs “places, not bases” to make ACE work, is concentrating on dispersal and improved air-defence systems for the likes of Guam. But the more it scatters, the more places it must defend.

Photograph: U.S. Air Force

American think-tanks say it is neglecting passive defences such as hardened aircraft shelters made of concrete. Portable pop-up shelters that can stop shrapnel would be useful, too, since China would have to fire more missiles to hit all of them, including empty ones, in a high-stakes shell game. Generals talk of dispersing planes within airfields and “flushing the force” by getting planes in the air before a missile can strike.

And yet, even during the ACE exercise, about two dozen fighter jets were parked close together in the open in Guam—convenient for pilots and ground crews, but an easy target for missiles. Similar concerns apply to fuel dumps and, indeed, ground crews. It is also unclear how far the air force is responding to newer threats, exemplified by Ukraine’s use of lorry-launched drones to destroy Russian bombers thousands of miles from the front.

In a war, America would fire at Chinese ships crossing the Taiwan Strait and other targets with long-range bombers, submarines and ground units lurking on islands. It would require vast amounts of air-to-air refuelling. Yet tankers and bombers are precious assets and, apart from the B-2, easy to see on radar. Moreover, America’s tanker fleet is more than 50 years old, on average. Mr Walton says China is optimising missile warheads to seek big planes such as tankers and airborne radars. Most may have to be held far back. But the farther planes must commute to war, the less effective they are.

Hiding and moving complicates China’s targeting, but also America’s logistical task. Fuel, crews and spare parts must be brought to the right place at the right time. Supply convoys would be juicy targets. Logisticians are thinking about how to move them through safer routes, via Australia. 3D-printing of spares in theatre will help, as will artificial intelligence. The lesson of the second world war, notes General Kevin Schneider, the head of Pacific Air Forces, is that “logistics and sustainment are absolutely key to generating air power.”

Co-ordinating an ever-shifting military kaleidoscope requires robust command-and-control systems. Combatants will seek to wreck each other’s data systems, not least by attacking satellites. Even so, top brass argue, data flows may be degraded but not permanently severed. Units will have “windows” of connectivity. Above all, they will rely on “mission command”, the ability to act without explicit orders in line with the commander’s intent. That initiative, say generals, gives America an advantage over rigidly controlled Chinese forces.

Is that enough to win? China may not need to defeat America, only hold it at bay for long enough to take Taiwan. War games suggest that, as China runs out of long-range munitions, American forces could move closer and defeat a landing, albeit at great cost. But America is short, too, and China’s greater industrial capacity may give it the means to outlast America.

Out along the edges

David Ochmanek of the RAND Corporation, another think-tank, reckons China has enough firepower to overwhelm airfields in the first island chain for as long as needed, and may soon be able to do so in the second chain. He argues that, close in, the air force must shift to drones that do not need runways. These would be bigger than the hand-held quadcopters ubiquitous in Ukraine, or even the loitering munitions that INDOPACOM is thinking of to create a “hellscape” for China near Taiwan. Air-combat drones with greater range, sensors and even weapons could be fired from rails, lorries or rockets, he argues.

Photograph: Pacific Air Forces

The air force is far from giving up on pilots, though this year it will start testing prototypes of the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA), a drone that for now will use runways and be controlled by crewed aircraft to augment their firepower. Yet even if drones can be made “runway independent”, they will still need ground crews, fuel and munitions.

For all the Trump administration’s boasts of a trillion-dollar defence budget, it has provided only a sugar rush in its “Big Beautiful Bill”. Its core defence-budget request is flat, ie, a cut after inflation.

After Tinian’s capture in 1944, construction teams started building North Field. B-29s were using it within six months. The modern restoration is slower. Eighteen months after starting work, engineers are still clearing vegetation. When might the first F-22 be able to use it? Enveloped in smoke and rain, the officer in charge shrugs. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, wants his armed forces ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. America, though, is still preparing for war with a peacetime mindset. ■

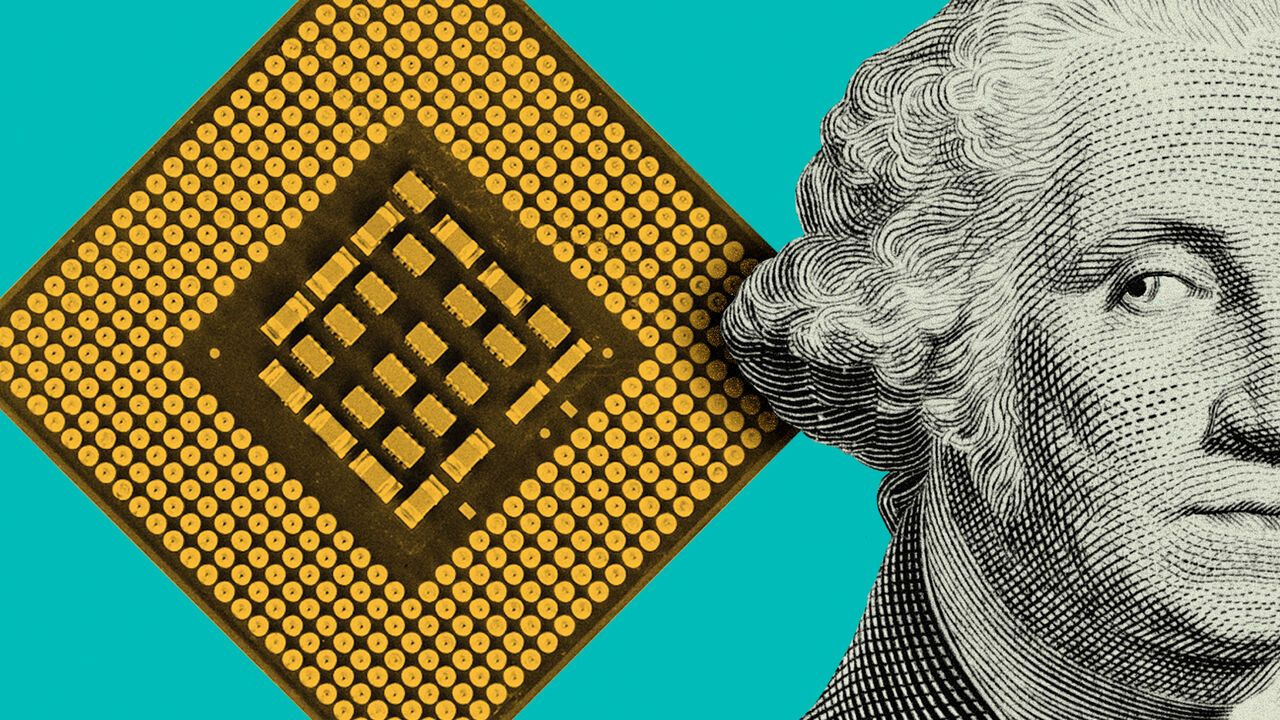

Business | Schumpeter

Trump wants to command bosses like Xi does. He is failing

His dealings with business borrow from China’s playbook

Illustration: Mari Fouz

Aug 13th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Ignore for a moment Donald Trump’s shakedown of Nvidia, in which he has allowed the world’s most valuable firm to resume limited exports of its artificial-intelligence (AI) chips to China in return for giving a 15% cut of the proceeds to Uncle Sam. Think instead of the argument about whether it is wise to let China have access to one of America’s most coveted technologies.

One side of the debate wants to flood China’s market. By permitting Nvidia to resume exports of its dumbed-down H20s, the argument is that it will reduce the incentive for China’s own chipmakers, such as Huawei, to develop substitutes. That will keep Chinese developers of generative AI hooked on American hardware, and make China less likely to invade Taiwan, where the bulk of the world’s cutting-edge chips are made. The other side takes a tougher approach. Its advocates, including this newspaper, contend that choking off access to the H20s, which are hot stuff in China even if sub-par by American standards, would slow the development of Chinese technology just enough for the US to secure an insurmountable lead in the AI race.

Mr Trump alluded to neither of these arguments when he confirmed on August 11th that Nvidia would resume selling H20s to China (AMD, a rival, will be able to sell some of its AI chips there, too). Instead he boasted of the haggling that took place between himself and Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s boss, to determine how big a cut America should get in return for the favour (and floated a similar approach for Nvidia’s “super-duper-advanced” Blackwell chips). Contrast that with the shrewder way China has used one of its most sought-after resources—rare earths—as a bargaining chip. When it comes to meddling with markets, America’s nickel-and-dimer-in-chief has much to learn from Xi Jinping.

A lot about the way Mr Trump has handled chip exports to China pales in comparison with how America’s rival has used rare earths for leverage. The American president’s strategy is capricious and confusing. In the space of three months, H20 sales have been banned and unbanned. His export levy probably violates Article 1 of the constitution, so it may face a legal challenge. By contrast, China’s approach is becoming more sophisticated. In recent months it has established a system of export controls that tries to track the end customer of commodities and spans hundreds of products, from sensors to manufacturing equipment.

So far Mr Trump’s approach appears neither to help America nor to hurt China. He has surrendered an important part of America’s national-security strategy for a pittance. Assuming H20 sales generate $20bn of revenues for Nvidia, the 15% surcharge would net $3bn—less than the cost of a new nuclear-powered submarine. Mr Trump has also given away one of America’s biggest sources of leverage before a proper deal is reached with China. Meanwhile, Mr Xi still has the rare-earths cudgel in hand, even if in the long run its use would spur efforts around the world to reduce dependence on Chinese supplies.

Mr Trump’s H20 gambit is muddle-headed. If his intent is to undercut Huawei and make China dependent on American chips, it would make more sense to dump cheap Nvidia products rather than raising their price through an export tax. That is the approach China has taken with great effect in its exports of solar panels, electric vehicles and drones (as well as, on occasion, rare earths). It knows the implications. Perhaps that is why it is pressing Chinese firms to shun the H20s.

Mr Trump’s ham-fisted approach to chips is not the only way in which he is proving to be a poor student of Mr Xi. Consider the pair’s efforts to assert themselves over their countries’ chief executives. When Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce giant, became too big for his boots in 2020, Mr Xi’s government did not just reprimand him. He was purged from public life for five years. Such was Mr Xi’s paranoia about the balance of power shifting from China’s Communist Party to its internet billionaires. Mr Trump is similarly determined to keep America’s bosses under his thumb. In the past week he has called directly or indirectly for the resignations of Lip-Bu Tan, the new boss of Intel, a chipmaker, and David Solomon, chief executive of Goldman Sachs, an investment bank. But he is more easily won over than Mr Xi. After Intel’s boss visited the White House on August 11th, Mr Trump hailed his career as an “amazing story”.

Mr Xi has likewise been more effective at whipping up patriotic fervour among companies in order to get them to do his bidding. China installs party cells to ensure they adhere to the government’s objectives. Mr Trump has used the threat of tariffs to encourage companies like Apple to reshore manufacturing to America. Yet America’s president receives mostly lip service. When Apple’s boss, Tim Cook, unveiled a $600bn, four-year investment pledge into America this month, it was more of an update than a change of plan. Not for nothing did he embellish it with a 24-carat gold gift to Mr Trump.

No big dealmaker

It is perhaps unsurprising that Mr Trump, who lacks Mr Xi’s authoritarian power, has been less effective at making his country’s businesses subservient to his political goals. It is also a relief. China’s approach of state capitalism may seem attractive to politicians in countries held back by democratic processes that make it difficult to effect change. But the model has its flaws. Growth in China has slowed and venture-backed entrepreneurial activity has waned in recent years. Businesses are mired in a brutal price war.

Thankfully, Mr Trump only dabbles in state capitalism. Even so, his approach is damaging. These days businesses in China can at least rely on a degree of coherence and consistency in policymaking. America Inc will not thrive amid chaos. ■

Business | Bartleby

Should you trust that five-star rating on Airbnb?

How to make sense of online customer reviews

Illustration: Paul Blow

Aug 14th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

It’s summer in the northern hemisphere. And as holidaymakers travel to unfamiliar places, that means demand for online customer reviews. Want to find a restaurant that won’t give everyone food poisoning, or the perfect accommodation for a city break, or a mosquito repellent that actually works? Whether you are looking on Tripadvisor, Airbnb or Amazon, you will almost certainly be guided by reviews from other people. Should you be?

The short answer is yes: better to have some information than none. But the flaws of online reviews are evident. For products with some objective measures of quality, there is a big gap between the views of punters and experts. A study in 2016 by Bart de Langhe of Vlerick Business School, in Belgium, and his co-authors found that user ratings for 1,272 items listed on Amazon.com bore little relation to either the verdict of Consumer Reports, an American product-testing organisation, or to their resale value.

That might be because consumers place greater value on more subjective things like a product’s brand. But if ratings are based on subjective criteria, then another problem arises: what if your tastes differ from other people’s? The best book ever, according to members of GoodReads, an online community of bibliophiles, is “The Hunger Games” by Suzanne Collins. You may agree, but plenty of people do not.

Another problem is that the people who bother to leave reviews and ratings may not be representative of consumers as a whole. In a study published in 2020, Verena Schoenmueller of Esade, a business school in Spain, and her co-authors examined the distribution of ratings left in around 280m reviews of more than 2m products and services on 25 different platforms. They broadly confirm a familiar pattern: a polar distribution of ratings, with more of them at the extremes of the scale than in the middle, and a skew towards more positive ratings.

There are lots of theories as to why online reviews follow this pattern. People who have chosen to buy something are already more likely to be satisfied with it. Extreme experiences, good and bad, are more likely to prompt reviews. Some write-ups are not real: estimates of the prevalence of fake reviews vary but they are certainly a problem, and one which generative AI may make worse.

The type of platform matters, too. Sharing-economy markets have a different feel. You could leave a four-star review for your Airbnb stay, but now that you have established a relationship with the hosts, and since they are also rating you, it’s much easier to just award five. A paper by Georgios Zervas of Boston University and his co-authors, last updated in 2020, found that average ratings for Airbnb properties are consistently higher than those for hotels on Tripadvisor.

In theory, businesses have an interest in soliciting as representative a sample of reviews as possible. Honest customer feedback is the best way to spot and fix problems, after all. In practice, the importance of good ratings, particularly for firms that are struggling for visibility, is an incentive for jiggery-pokery. A study from 2013 by Dina Mayzlin of the University of Southern California and her co-authors suggested, for example, that small, independently owned hotels generated more positive fake reviews on Tripadvisor than branded hotel chains.

If the incentives of businesses and consumers do not always align, then platforms have an interest in ensuring that reviews are as informative as possible. Weighting scores by the number of reviews that a customer writes could help mitigate the problem of polarity; Ms Schoenmueller’s research suggests that the more reviews a person writes, the less extreme their ratings.

But consumers can also help themselves. Mr de Langhe’s research suggests that people put too much weight on the overall average rating. The absolute number of reviews is a better indicator of actual popularity. And it is the detail in a review that tells you whether the person writing it prefers dystopian young-adult fiction to other genres, or whether a diner values buzz or the ability to hear themselves think. Reviews, then, are even more useful if you read them. ■

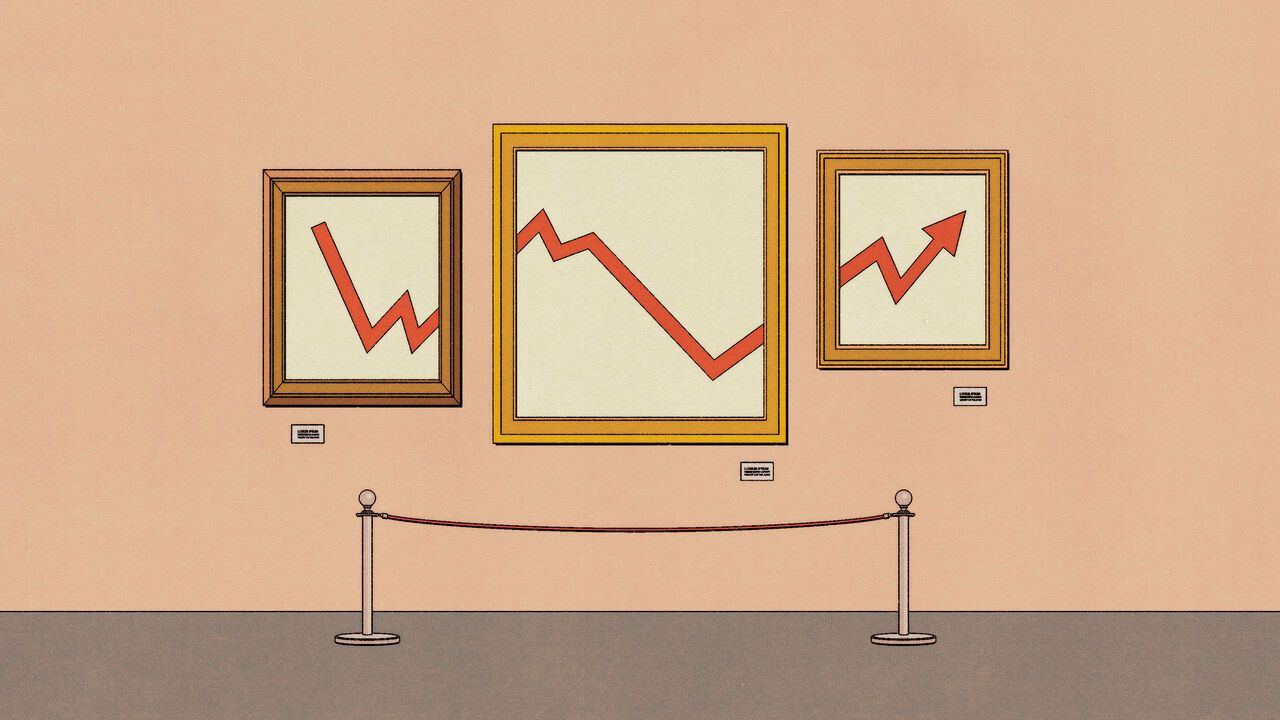

Finance & economics | Free exchange

What 630,000 paintings say about the world economy

Kandinsky, Monet and Rembrandt were economists as well as artists

Illustration: Álvaro Bernis

Aug 14th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Two figures share a table, but not much companionship, in a Parisian café. The man looks distracted, a pipe gripped in his mouth. The woman, eyes down, shoulders slumped, nurses a glass of moss-green absinthe. The painting, unveiled by Edgar Degas in 1876, boasts several titles (“L’Absinthe”, “In a Café” and others). It also divides opinion. One viewer, appalled by the woman’s loose morning shoes and the thought of her soiled petticoats, saw the painting as a cautionary tale against idleness and “low vice”. He then changed his mind. “The picture is merely a work of art”, he later said, “and has nothing to do with drink or sociology.”

Great paintings can inspire entire volumes of interpretation. The ArtEmis project, which concluded in 2021, took a more concise approach. It recruited people to log their emotional responses to thousands of paintings in a digital archive. These “annotators” could choose one of eight feelings, each illustrated by an emoji. Based on this exercise and a later, bigger project called ArtELingo, complex works of art like Degas’s 1876 masterpiece can be succinctly summarised in a handful of numbers. When asked how L’Absinthe makes them feel, over three-fifths of people choose “sadness”. Almost a fifth choose amusement. About a tenth pick contentment (perhaps they appreciate roomy footwear). None chooses the other listed emotions: anger, awe, disgust, excitement or fear. A few pick a ninth, residual option: “something else”.

ArtEmis carried out polls for 80,000 or so paintings. The project also tried, with mixed success, to emulate human responses with artificial intelligence, training a model to predict how people might feel. A new paper, entitled “State of the Art”, by Clément Gorin of the Sorbonne School of Economics, Stephan Heblich of the University of Toronto and Yanos Zylberberg of the University of Bristol, tries to do the same. The authors trained a model on 70% of the paintings, and tested if it could predict poll results for other works. Once satisfied, they unleashed this automated aesthete on over 630,000 paintings from the 15th century onwards.

The trio describe the data as a “historical time series of emotions”, subscribing to a theory of art laid out by Tolstoy in 1898. He believed that artists could transmit feelings to an audience through their work, as if by contagion. “The stronger the infection, the better is the art as art.” If paintings do communicate in this way, then, in principle, the steps of transmission can be retraced in the reverse direction, from audience back to origin. The emotional response of people today to an artwork of yesteryear tells you something about its creator and the world that shaped them.

Messrs Gorin, Heblich and Zylberberg show that painters have their own emotional signatures. Kandinsky tends to excite or amuse, Monet evokes contentment, Rembrandt sadness. If you simply know the artist, you can explain 40-50% of the variation in art’s emotional valence, the authors calculate. But that leaves a lot to be explained by other factors. There are, for example, small but systematic differences between countries in the impact of their art. Pick a random year and painting, and the chances that it will evoke contentment are 31-32% if it was produced in Denmark or Britain but only 26% if in Italy or Spain. These probabilities also respond to historical upheavals, such as the Spanish civil war.