The Economist Articles for Aug. 5th week : Aug. 31th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.08.23조회수67 목록 댓글 0

The Economist Articles for Aug. 5th week : Aug. 31th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | All-American silicon

America’s fantasy of home-grown chipmaking

To remain the world’s foremost technological power, the country needs its friends

Aug 21st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

How low mighty Intel has fallen. Half a century ago the American chipmaker was a byword for the cutting edge; it went on to dominate the market for personal-computer chips and in 2000 briefly became the world’s second-most-valuable company. Yet these days Intel, with a market capitalisation of $100bn, is not even the 15th-most-valuable chip firm, and supplies practically none of the advanced chips used for artificial intelligence (AI). Once an icon of America’s technological and commercial prowess, it has lately been a target for subsidies and protection. As we published this, President Donald Trump was even mulling quasi-nationalisation.

More than ever, semiconductors hold the key to the 21st century. They are increasingly critical for defence; in the ai race between America and China, they could spell the difference between victory and defeat. Even free-traders acknowledge their strategic importance, and worry about the world’s reliance for cutting-edge chips on tsmc and its home of Taiwan, which faces the threat of Chinese invasion. Yet chips also pose a fiendish test for proponents of industrial policy. Their manufacture is a marvel of specialisation, complexity and globalisation. Under those conditions, intervening in markets is prone to fail—as Intel so vividly illustrates.

To see how much can go wrong, consider its woes. Hubris caused the firm to miss both the smartphone and the ai waves, losing out to firms such as Arm, Nvidia and tsmc. Joe Biden’s CHIPS Act, which aimed to spur domestic chipmaking, promised Intel $8bn in grants and up to $12bn in loans. But the company is floundering. A fab in Ohio meant to open this year is now expected to begin operations in the early 2030s. Intel is heavily indebted and generates barely enough cash to keep itself afloat.

Illustration: Deena So'Oteh

The sums needed to rescue it keep growing. By one estimate Intel will need to invest more than $50bn in the next few years if it is to succeed at making leading-edge chips. Even if the government were to sink that much into the firm, it would have no guarantee of success. The company is said to be struggling with its latest manufacturing process. Its sales are falling and its plight risks becoming even more desperate.

The Biden administration failed with Intel, but Mr Trump could make things worse. He has threatened tariffs on chip imports, and may try to browbeat firms such as Nvidia into using Intel to make semiconductors for them. These measures might buy Intel time but they would be self-defeating for America. Chipmaking is not an end in itself but a critical input America’s tech sector requires to be world-beating. Forcing firms to settle for anything less than the best would blunt their edge.

What should America do? One lesson is not to pin the nation’s hopes on keeping Intel intact. It could sell its fab business to a deep-pocketed investor, such as SoftBank, which has reportedly expressed interest in buying it and this week announced a $2bn investment in Intel. Or it could sell its design arm and pour the proceeds into manufacturing. Intel may fail to catch up with TSMC even then. Either way, the federal government should not throw good money after bad. Taking a stake in Intel would only complicate matters.

That leads to a second lesson: to look beyond Intel and solve other chipmakers’ problems. tsmc is seeking to spread its wings. It is running out of land for giant fabs in Taiwan and its workforce is ageing. It has already pledged to invest $165bn to bring chipmaking to America. A first fab is producing four-nanometre (nm) chips and a second is scheduled to begin making more advanced chips by 2028. Samsung, a South Korean chipmaker that is having more success than Intel, is setting up a fab in Texas. But progress has been slow: Samsung and TSMC have both struggled with a lack of skilled workers and delays in receiving permits.

The last lesson is that, even if domestic chipmaking does make America more resilient, the country cannot shut itself off from the rest of the world. One reason is that the supply chain is highly specialised, with key inputs coming from across the globe, including extreme-ultraviolet lithography machines from the Netherlands and chipmaking tools from Japan. The other is that Taiwan and its security will remain critical. Even by the end of this decade, when tsmc’s third fab in America is due to begin producing 2nm chips, two-thirds of such semiconductors are likely to be made on the island. TSMC’s model is based on innovating at home first, before spreading its advances around the world.

To keep America’s chip supply chains resilient, Mr Trump needs a coherent, thought-through strategy—a tall order for a man who governs by impulse. No wonder he is going in the wrong direction. On Taiwan he has been cavalier, confident that China will not invade on his watch, while failing to offer the island consistent support. His tariffs on all manner of inputs will raise the costs of manufacturing in America; promised duties on chip imports will hurt American customers. He thrives on uncertainty, but chipmakers require stability.

A sensible chip policy would make it attractive to build fabs in America by easing rules over permits and creating programmes to train engineers. Instead of using tariffs as leverage, the government should welcome the imports of machinery and people that support chipmaking. Given the bipartisan consensus on the importance of semiconductors, the administration should seek a policy that has Democratic support—with the promise of continuity from one president to the next.

Economic nationalists should also see the progress of chipmakers in allied countries as a contribution to America’s security. Samsung is aiming to start producing 2nm chips in South Korea later this year. Rapidus, a well-funded chipmaking startup in Japan, is making impressive progress. Both countries have a tradition of manufacturing excellence, and may have a better shot at emulating Taiwan.

The chipmaking industry took decades to evolve. It is built for an age of globalisation. When economic nationalists build their policies on autarky, they are setting themselves a needlessly hard task—if not an impossible one. ■

Asia | Poll politics

How fair are India’s elections?

Rahul Gandhi, an opposition leader, raises some uncomfortable questions

Rallying behind RahulPhotograph: Shutterstock

Aug 21st 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

An address with a house numbered zero; a household with 80 people; a person named “dfojgaidf”. Bureaucratic snafus are common in India. But according to Rahul Gandhi, these irregularities in Mahadevapura, a suburb in the city of Bangalore, were part of a grander “vote chori” (vote theft) scheme that helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) win last year’s general election. In a detailed presentation this month Mr Gandhi, the leader of Congress, India’s main opposition, said there were thousands of such examples and accused the Election Commission of India (ECI), the constitutional body that organises the country’s polls, of colluding with the BJP.

Mr Gandhi’s allegations have rocked the ECI, which was already under pressure. On June 24th it began a “Special Intensive Revision” of the electoral rolls in Bihar, ahead of polls due there by November. The exercise has been controversial for both its timing and execution. Such electoral revisions are rare—the last one in Bihar was in 2003—and are usually planned in great detail. This revision was announced abruptly and will be completed for a state with 130m people in a matter of weeks. Questions also hover over the review’s result, in which 6.5m voters were struck from the list (approximately 8.3% of the total voter count).

The ECI has dismissed such concerns. It says that its deletions were due to deaths, duplicate entries and migration. The commission has been even more defiant in the face of Mr Gandhi’s allegations. On August 17th Gyanesh Kumar, the ECI’s boss, issued an ultimatum to the Congress leader, ordering him to file an affidavit to the courts under oath outlining his charges or to apologise to the country. “There is no third option,” he said.

The controversies add to growing concerns about the integrity of India’s polls. For years, the ECI has been seen as the bedrock of Indian democracy, earning plaudits for organising the world’s biggest elections. On indices compiled by the V-Dem Institute, a Swedish think-tank, India’s electoral process has long outperformed its peers in the region. But its score has been sliding over the past decade, dragged down by declines on several measures, including those tracking voter irregularities and freedom for parties to operate.

One explanation lies in the nature of Indian politics. Since 2014 the BJP has been the country’s dominant political power. In the era of coalition politics that preceded its rise, it was in everyone’s interests for the ECI to ensure a level playing-field. But today, in an era of single-party hegemony, that neutralising force has lost its power. The head of the ECI, for instance, is nominated by a panel, which includes the prime minister, leader of the opposition and another minister—and is hence skewed towards the executive. (The Supreme Court had recommended that the third member should be the Chief Justice of India, but that was ignored by the government.)

Similarly, critics argue that the model code of conduct, which the ECI uses to monitor election campaigns, is unfairly applied. They say clear violations, such as inflammatory language, by BJP leaders, including the prime minister, Narendra Modi, have been ignored. In a new study examining the integrity of the general election in 2024, Milan Vaishnav, a political scientist, writes that there are signs that elections in India “are free but not necessarily always fair”.

For now, the opposition has been galvanised by the issue and is pressing for reforms. On August 17th Mr Gandhi embarked on a “Voter Adhikar Yatra” (Voter Rights March) in Bihar to educate people about their electoral rights. Opposition parties have even mooted impeaching Mr Kumar, the election commissioner. But such changes require legislation passed by parliament, where the BJP and its allies enjoy a comfortable majority.

The BJP itself has dismissed allegations of collusion and shown little appetite for change—despite seemingly acknowledging electoral irregularities. A week after Mr Gandhi’s presentation, Anurag Thakur, a BJP parliamentarian, accused the Congress of conducting its own vote chori, pointing to alleged “doubtful voters”.■

China | Judicial independence

Hong Kong’s courtroom dramas

Jimmy Lai’s trial raises questions about how justice now works

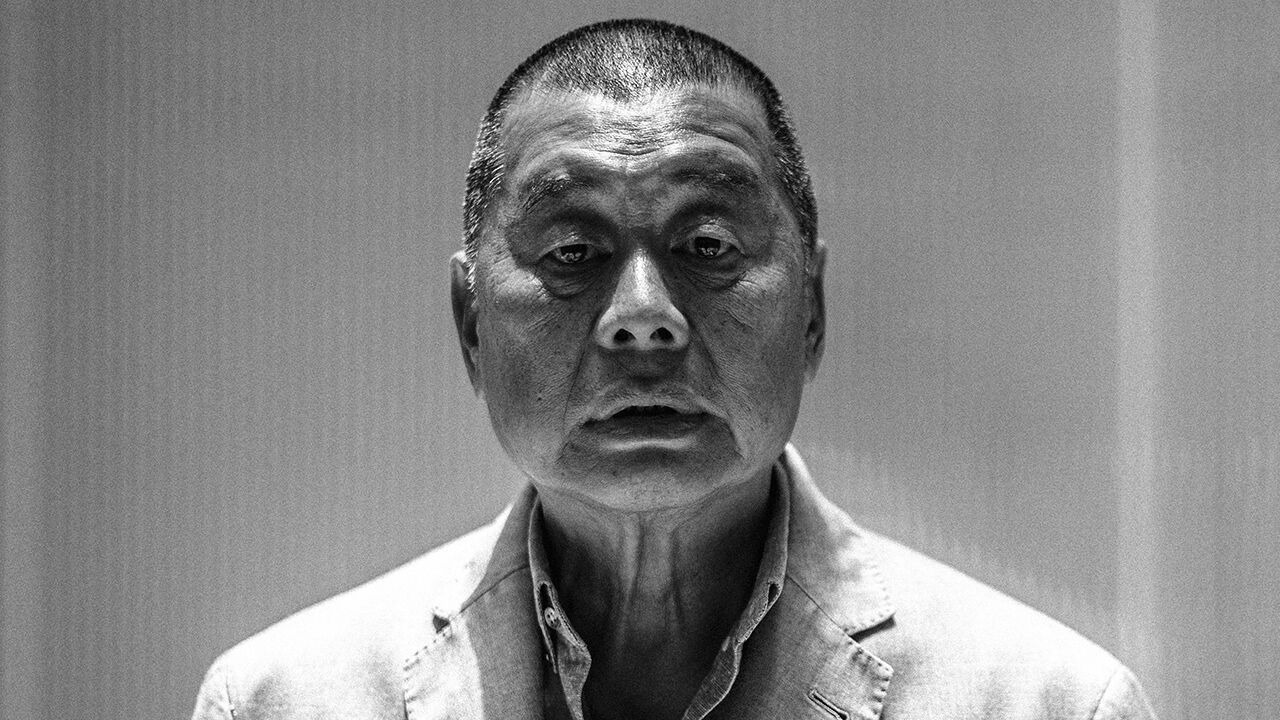

Photograph: AFP

Aug 21st 2025|Hong Kong|8 min read

Listen to this story

CLOSING ARGUMENTS are under way in the trial of Hong Kong’s most famous media mogul. Jimmy Lai’s publications cheered the millions who marched against the territory’s government in 2019. The charismatic billionaire could have fled. But Mr Lai stayed, and now stands accused of sedition and collusion with foreign forces. The verdict is expected to be delivered in a few weeks or months; few observers doubt that the 77-year-old will be found guilty. Already serving another jail term, he could face a sentence of life in prison.

In the wake of the unrest, which turned violent, China’s ruling Communist Party engineered sweeping changes in Hong Kong’s laws to prevent further upheaval. These are being used to crush even peaceful activism that is deemed a threat to the party or the government in Hong Kong.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to be after Britain passed Hong Kong back to China in 1997. China promised to preserve freedoms. It allowed Hong Kong to keep a common-law legal system, which set the bar high for putting dissenters in jail. But two new laws have transformed the legal landscape. The first was the National Security Law (NSL), promulgated by the legislature in Beijing in 2020. It created sweeping, fuzzy categories of crime that Hong Kong had not known before, such as secession, subversion and the collusion of which Mr Lai stands accused. The other was last year’s “Article 23 legislation”. It imposed tougher sentences for offences related to national security and ditched a requirement that the crime of sedition (which existed before the NSL) should be linked to violence.

Business people still seem bullish—increasingly so, even. The American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong regularly surveys its members about how they feel. In January 83% said they were confident in the territory’s legal order. In 2022 only about a quarter felt that way. Their assumption seems to be that the authorities will target activists and leave business alone. But the new laws feel oppressive to many Hong Kongers. Large, peaceful protests, once common, no longer happen. Government critics fear speaking out.

The legislation also weighs heavily on the courts. Judges lack precedent they can draw on for determining how to understand new legal parameters. Almost all the 78 concluded cases under the NSL have resulted in guilty verdicts, but appeals abound. It may take years for these to work through the system. That process will help provide more clarity about where exactly the law’s red lines are.

Legal blows against dissent raise questions about Hong Kong’s judicial independence. The territory still ranks highly on global rule-of-law indices. In 2019 it was placed 16th by the World Justice Project, an American NGO. America was 20th on its list of 126 countries and territories. Since the imposition of the NSL Hong Kong has fallen only slightly to 23rd (out of 142), keeping its lead over America, which trails at 26th. (Mainland China has fallen from 88th in 2020 to 95th, just above Tanzania.)

But Hong Kong’s overall score masks a sharp deterioration in one category: fundamental rights. In this area it has fallen from 33rd—six places behind America—to 62nd (25 behind). It is still far ahead of mainland China (close to bottom at 139th). Clearly, however, it has changed, with its courts now regularly jailing people for dissident activities that once would have been allowed. Critics wonder if judges are taking cues from Chinese officials, and to what degree the system is becoming more like that of the mainland. There the Communist Party, not the judiciary, determines the outcome of cases that involve matters relating to its interests.

Wigs and gowns

Officials counter that the territory’s judicial system is as robust as ever. A senior adviser to Hong Kong’s government, Ronny Tong—himself a lawyer—dismisses suggestions that the judiciary is pliant. He calls allegations of political pressure on judges a “very unjustified myth”. Leaders in Beijing are adamant that they want to protect the territory’s common-law system.

In cases not involving dissent, this system indeed remains intact. And even in trials of political activists, Hong Kong’s courts still operate very differently from those of the mainland, where such events are often pro-forma, usually wrapped up in days and without media access. In Hong Kong they can last months, with evidence and witness testimony argued over in detail. Journalists can watch and report. There is no sign that the Communist Party intervenes directly in trials as it does on the mainland, where outcomes in politically sensitive cases are determined by its shadowy “political-legal” committees.

Yet the party has other ways of influencing outcomes. The NSL and Article 23 legislation allow related trials to be held without a jury—they now always are. Verdicts in these sorts of case are reached by three judges chosen from a special pool. Its members have renewable year-long terms, but the NSL says that if a judge “makes any statement or behaves in any manner endangering national security” while doing the job, they can be dismissed from the pool. China’s rubber-stamp parliament has the final say in the NSL’s interpretation. The Communist Party sees criticism of its rule as a national-security threat.

Disquiet is mounting. The territory’s Court of Final Appeal (CFA) has invited both local and overseas judges onto its bench since the handover. The latter came from other common-law jurisdictions such as Australia and Britain and took up temporary seats. Five foreigners have quit the CFA since 2022; some have cited concerns about the political environment. (There is little chance a visiting overseas judge would be chosen to adjudicate an NSL case in the CFA, though foreign judges who are resident in Hong Kong have done so.)

One trigger was a case involving 47 people who were accused of subversion for their roles in organising an unofficial primary election to maximise the chances of opposition politicians taking control of the legislature, and using that majority to force Hong Kong’s leader to step down (its constitution allows that). Two were acquitted; the remainder were sentenced to between four and ten years in prison last year.

Citing their treatment, Lord Sumption, formerly of Britain’s Supreme Court, left the CFA after four and a half years in service. “It seemed to me that in cases, particularly criminal cases about which the Chinese government was known to feel strongly, the courts were not prepared to operate independently of the wishes of China,” he says. Hong Kong’s government rejects his views. In a statement of nearly 3,000 words in June 2024, it declared that any suggestion that judicial independence has been compromised “would be utterly wrong, totally baseless, and must be righteously refuted”.

They face difficult times in ill-charted territoryPhotograph: Alamy

For judges, these are difficult times in ill-charted territory. Lord Sumption recalls a “very senior” one telling him that the West offers only second passports and moral lectures. “We have nowhere else to go, unlike you,” he quotes the judge as saying. “What are we to do? We are not able to conduct a guerrilla war against China. And if we tried, we’d probably get something worse. We have to face realities.”

Many of the judges may not be liberals, anyway. China insists that they must be “patriotic”, which in its view involves accepting the party’s monopoly of power. A law professor says a few have not studied human-rights law. The NSL requires Hong Kong to adhere to the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. But judges know that any attempt to apply these principles in a way that prevents the party getting its way could end in frustration. The party makes clear its views using its local mouthpieces, especially two newspapers Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. These portray even peaceful protesters as guilty of heinous crimes against the state.

Many appeals are likely to end up eventually in the CFA; some may be upheld. In March it quashed the convictions of three former members of a now-disbanded pro-democracy group, the Hong Kong Alliance. It was a rare exoneration of activists by the territory’s highest court. But it was on a technicality. One of them, along with fellow former leaders of the group, is expected to be put on trial in November on more serious charges. And when the party’s interests could be affected, the Hong Kong government occasionally invites China’s parliament to step in. In 2022 the national legislature allowed the territory to sidestep a CFA ruling that Mr Lai’s defence team could use an overseas barrister.

Over time, the judiciary’s strength may erode as the best lawyers in Hong Kong avoid taking on the job. “A lot of the gloss of a judicial appointment disappeared with the feeling that the judges are no longer as independent as they used to be,” believes Lord Sumption. The law professor says new law students barely remember the unrest six years ago. They “do not associate 2019 with anything positive”, he says. Neither does the Communist Party. ■

United States | No-man’s-land

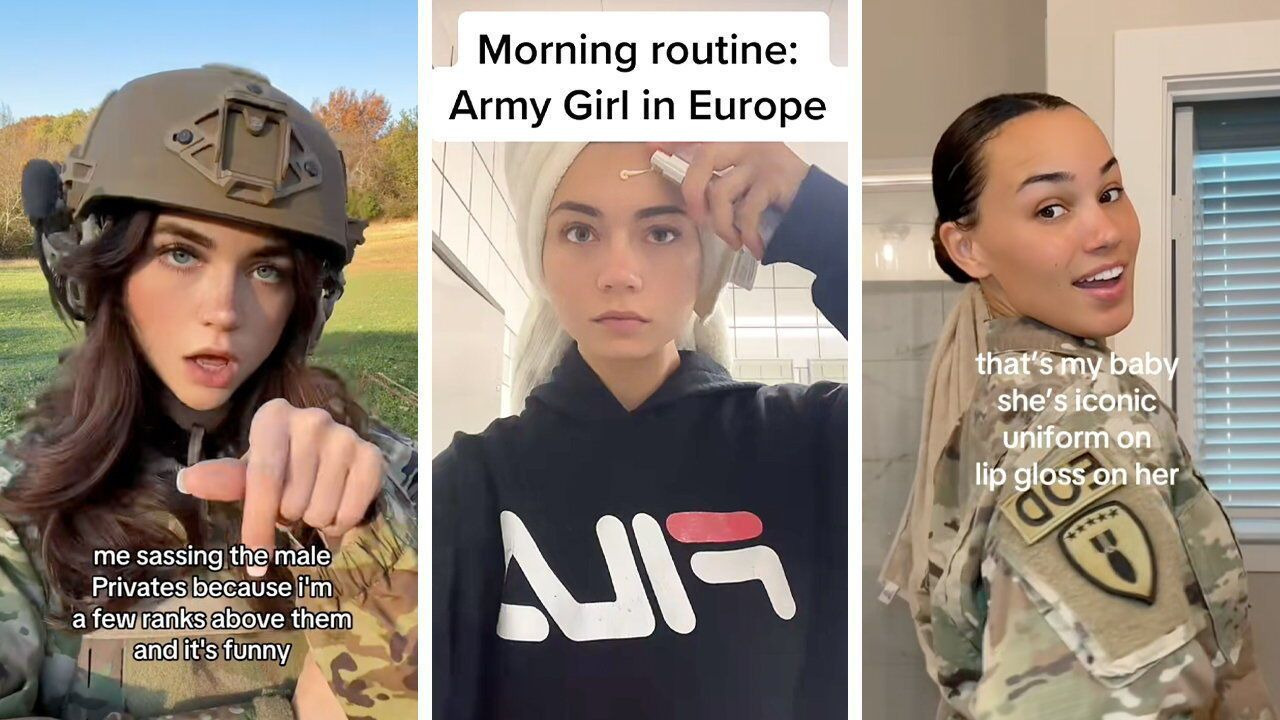

The young American female soldiers of TikTok

An app that Congress considers to be a national-security risk helps to recruit soldiers

Photograph: Courtesy of lunchbaglujan/lifewithm0nica/TikTok

Aug 19th 2025|2 min read

Listen to this story

Before Pete Hegseth became defence secretary, it is fair to say that he did not always see the point of women in some parts of the army. “Our military runs on masculinity. It’s not toxic at all, it’s necessary,” he once wrote. To win confirmation by the Senate he moderated his views: all combat roles remain open to women. That is just as well. Finding enough recruits is hard. Strangely, one thing that helps the armed forces do so is an app that Congress has tried to ban on national-security grounds.

Enlist in “#MilTok”, TikTok’s niche for military content, and you may find a lieutenant doing her skincare routine, a navy officer on a nursery run, or an air-force operator vlogging mid-flight. They command thousands of followers and millions of views, reflecting a broader shift within the ranks.

While the number of male active-duty members has fallen by 10% since 2005, the number of their female counterparts has grown by 12% over the same period. Still, women have had a tough time assimilating. As recently as 2023, 13% of active-duty women experienced gender discrimination compared with 1.4% of active-duty men, according to the Department of Defence.

Some of these women turned to TikTok—a platform which offered recognition when they were overlooked and support when they were isolated. It soon became a place for talking about issues that male counterparts rarely encountered, such as adapting the female uniform or navigating grooming regulations. “Women didn’t have other women to look up to or talk to about their struggles,” says Monica Smith, a first lieutenant in the army’s bomb-disposal unit (pictured above).

But not all attention has been welcome. The comments sections on #MilTok are often littered with lewd or disparaging remarks. Peers and superiors in the Pentagon are also wary, especially since the Chinese-owned app is deemed a security risk. “When my unit heard I had a TikTok, people were really sensitive about it,” says Lieutenant Smith. It doesn’t help that some servicewomen court controversy, like Hailey Lujan—an influencer known for pairing cutesy antics with graphic references. In one video, she dances in tactical gear to a Charli XCX song while joking about bleeding out in the trenches.

Such posts have fuelled online speculation that these women are “psy-ops”: psychological-operations specialists deployed to influence perceptions of the military. Most reject that label. They are not shouting about the institution—they just want to be heard within it. As Ms Lujan wrote (on Instagram), “It’s simply a new method of standing up for what I believe in, by all silly means necessary.” ■

The Americas | More than manga and microwaves

Why Mexicans love Japan and Korea

Drama, language and music in one direction; rising numbers of Mexican tourists in the other

Land of the rising sons who do taekwondoPhotograph: AP

Aug 21st 2025|AGUASCALIENTES|4 min read

Listen to this story

Over brightly coloured jelly sodas at Kai Bai Bo, a Korean-themed café in Mexico City, Alejandra Chávez and Adriana Guzmán discuss their shared passion: BTS, South Korea’s global pop phenomenon. “It was an instant click,” says Ms Chávez, a 23-year-old who discovered the band just before the pandemic. “They make me happy.” Ms Guzmán, 24, nods: “They’ve changed my life. When I stop listening to them, I feel negative.”

These two young women are part of the Mexican chapter of the BTS Army, a global fan collective that mobilises like a campaign machine. Together with other volunteers they organise streaming parties, raise funds for murals and explain voting rules to newcomers baffled by the mechanics of K-pop fandom (it revolves around getting out the vote for the band in various polls and awards). Their group has even decorated boats with BTS-themed art. “Sometimes we pay out of our own pockets,” says Ms Chávez. “It’s how we show love.”

That love is in bloom. Millions of Mexicans have developed affection not just for Korean pop, but for Japanese anime (animated films, TV and videos), as well as the languages, food, fashion and values of both countries. There are fan clubs in the capital, Japanese-language schools in Aguascalientes and Korean-cooking classes in Querétaro. What was once a niche taste is becoming a national appetite.

Japan’s was the first East Asian culture to find fans in Mexico. That began when dubbed anime shows started airing on Mexican television in the late 1970s, says Edgar Peláez, a Mexican academic at Lakeland University in Tokyo. Real growth began in the 1990s. Japan’s asset-price bubble piqued global interest and, later, its government pushed culture as a form of soft power. In Mexico, that coincided with the liberalisation of the economy, the privatisation of state broadcasters and the arrival of Japanese toy companies such as Bandai, leading to a flood of content and merchandise. Mexican dubbing studios became regional hubs in which anime was adapted for Latin American audiences.

Foreign investment also played a role in the boom. Nissan, a Japanese carmaker, opened its first assembly plant in Aguascalientes in 1992. The city is now home to a large Japanese community, part of which has put down roots, giving rise to second-generation nikkei families.

More recently, Japanese cuisine has become popular. Takeya Matsumoto, who runs several restaurants in Mexico City, says that when he arrived from Japan in 2007 there were very few. “Now all sorts of Japanese food is available,” he says.

These cultural imports seem to have spurred demand for travel to Japan; in 2024 150,000 people flew there from Mexico, the highest tally on record. While small compared with the number of people visiting Japan from other countries, arrivals from Mexico were up by 60% from 2023, the fastest year-on-year growth of any country.

Korea break

Korea’s culture has followed that of Japan to become, if anything, even more popular. In 2023 South Korea’s global cultural exports—including music, TV dramas, films, fashion and beauty products—were worth a record $12.4bn, according to the country’s culture ministry, exceeding even exports of home appliances. Mexico played its part. The Korean Cultural Centre in Mexico City says the number of Mexicans enamoured of hallyu, the wave of Korean culture which started sweeping the world starting in the late 1990s, is estimated to have jumped from 6.7m in 2023 to more than 11m in 2024. Korean-language courses are heavily oversubscribed. Korean skin-care products, once hard to find, are now sold in boutiques and supermarkets. K-dramas are likely to appear in social-media feeds alongside telenovelas.

Mexicans seem attracted to these cultures for different reasons. Many students of Japanese are learning because they want to work there; others want to read manga or prepare for a trip. Many emphasise the more traditional parts of the culture, such as origami or tea ceremonies. Soraya Aguirre of Cendics México, a language school in Aguascalientes, says demand for Japanese lessons has surged in the past five years. By contrast, students of Korean are often driven by pop culture. They skew younger and female. Many, like Ms Chávez and Ms Guzmán, teach themselves Korean by studying song lyrics and YouTube videos, rather than taking formal classes.

Booming cultural imports are likely to continue as Mexico’s relationship with both countries deepens. Japan and Mexico have had a free-trade agreement since 2005. Asian firms have been investing heavily in northern and central Mexico. South Korea and Mexico are exploring new trade ties. Diplomatic efforts—from scholarships to taekwondo parades—are becoming commonplace.

China is also making inroads, albeit of another sort. In cities like Aguascalientes, interest in Chinese is still limited but gradually rising—and driven more by economic pragmatism than popular appeal. Students cite job prospects and business ties rather than fandom and cultural allure. Confucius Institutes have opened at several Mexican universities. But, for now at least, China’s soft power in Mexico is more of the boardroom than the bedroom wall.

In the background, Mexican perceptions of Asian cultural fandom have shifted. Being a fan of BTS used to provoke bullying, says Ms Chávez. Now, she says, it is finally cool. ■

After 20 years in power, Bolivia’s socialists crash out of it

That was not the only surprise in the general election’s first round

Photograph: AP

Aug 21st 2025|1 min read

Listen to this story

In a general election on August 17th Rodrigo Paz (pictured), a centrist senator, chalked up a shock win with 32% of votes; polling had predicted closer to 10%. He will run off against Jorge Quiroga, a right-wing former president who led his coalition to second place, on October 19th. And in third place? Spoiled ballots. Evo Morales, a former president who was forced out of the left-wing Movement to Socialism (MAS) and barred from running by a court ruling, had called for a “null vote” in protest. People listened. Eduardo del Castillo, the permitted MAS candidate, won just 3%—barely enough to maintain the party’s legal status. That marks the end of nearly 20 years of MAS rule, and assures a rightward tilt for the country’s politics in October.

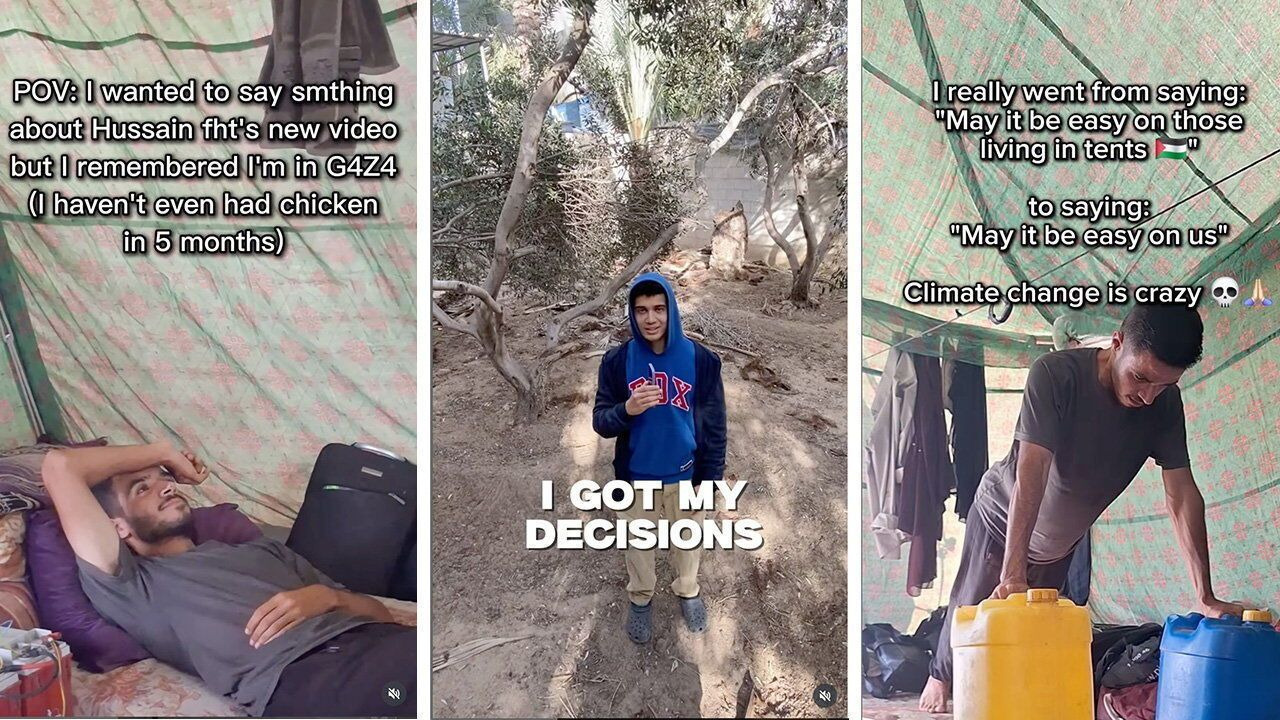

Middle East & Africa | Voices from the strip

Gaza’s Gen-Z influencers

They include a bodybuilder, a would-be American-college student and skateboarders

Photograph: Instagram/gym_rat_in_gaza/ Omar.shareed

Aug 21st 2025|BEIRUT|2 min read

Listen to this story

An amateur bodybuilder. A teenager admitted to Dartmouth College in America. A gang of skateboarders. They are not obvious chroniclers of bombs and famine. But they are among Gaza’s most dogged witnesses—the Generation-Z Palestinians who have posted online over 22 months of war.

Audiences can be vast: a handful have millions of followers, many of them count hundreds of thousands of followers from around the world. Their role matters all the more because Israel bars foreign journalists from working freely in Gaza, and because hundreds of Palestinian reporters have been killed. For those looking for Palestinians’ own stories about life in Gaza, TikTok and Instagram, not cable television, offer the most unfiltered version.

On Instagram Mohammed Hatem, an amateur bodybuilder who goes by the name “Gym Rat in Gaza”, documents his muscles wasting away for lack of protein. He has almost 400,000 followers and has appeared on some fitness podcasts in America.

In a recent interview, he described how he was getting just 1,200 calories, on average per day, barely half the 2,400 he calculates he needs to stay fit, he says. “As much as I try to optimise training and nutrition to still make results, my main focus in it was for my mental side. I would like to stay committed to this little bit of my daily routine,” he told one podcaster.

Some of Mr Hatem’s videos feature witty clips about the lack of chicken in Gaza. Others show him giving fitness consultations to clients outside Gaza or gathering his belongings for yet another evacuation.

Omar Shareed, who won a place at Dartmouth College in America, posts about the bureaucratic struggle to leave Gaza and take up his studies. He pleads with his followers to help him with this.

Ceasefire or not, Gaza’s influencers continue to document birthdays, weddings and the daily struggle to stay alive and get enough food. Life goes on—except when it does not. Earlier this year Yaqeen Hammad, an 11-year-old known as “Gaza’s youngest influencer”, was killed in an Israeli airstrike.■

Europe | Charlemagne

Trump wants a Nobel prize. Europe can exploit that to help Ukraine

But beware the pitfalls of photo-op peacemaking

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Aug 21st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

Foreign dignitaries invited to the White House know a thoughtful gift can help lubricate the wheels of diplomacy. Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, went the safe route as he arrived in Washington this week, offering a golf club to his golf-mad host, Donald Trump. Past gifts from abroad have included a presidential private jet from Qatar, a posh set of Mont Blanc fountain pens from Angela Merkel (no match for the presidential Sharpie) and a portrait of one Donald J. Trump made with gemstones, courtesy of Vietnam. As a parade of European leaders set out for Washington to support Mr Zelensky, what memorable trinket from their home continent could they possibly bestow upon the president who has everything? Mr Trump, as it happens, no doubt had something in mind. For there is one bauble from Europe he has alluded to repeatedly of late: the medal awarded to recipients of the Nobel peace prize. His pining for the acclaim granted every year by a committee appointed by the Norwegian parliament is turbocharging American diplomacy in a way that might both encourage Europe and cause it to panic.

An obvious plot offers itself to the deft diplomat: could Europe, the continental home of the Nobel prizes, dangle the prospect of a shiny medal and an Oslo banquet as a sort of carrot to lure Mr Trump onto their side when it comes to Ukraine? Alas, the committee that decides on the prize, comprised of five obscure Norwegian grandees drawn from politics and civil society, seems above such antics. Repeated assurances from Mr Trump that he is not campaigning for the gong, nor thinks he will ever get it, are taken as sure signs he desperately wants it. (A recent phone call to the Norwegian finance minister, in which the matter of the Nobel reportedly came up alongside threats of tariffs, is another clue.) Mr Trump wants his dealmaking skills to be recognised in endeavours beyond the building of gaudy skyscrapers, and there is no greater arena than diplomacy. The global elites sneer at mere moneymaking. But recognition from Oslo is worth much more than the medal’s weight in gold (about 200 grams, or $20,000).

The prospect of joining Teddy Roosevelt, Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King as a Nobel laureate (best not to mention Barack Obama) has sent Mr Trump into “peacemaker-in-chief” mode. In recent months he has boasted of spreading harmony faster than the world’s baddies can spark strife. Somewhat improbably he has claimed credit for ending six (or sometimes seven) wars in as many months. Where does the fellow find the time? At least in his own mind, amity now prevails between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda; there is nothing but fraternal love between India and Pakistan; the guns will forever be silent in the conflicts between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Iran and Israel, Thailand and Cambodia. The repentant warmongers, among them Binyamin Netanyahu of Israel (not so repentant when it comes to Gaza), have backed Mr Trump for the Nobel.

Yet to secure the gong Mr Trump knows he will have to tackle the thorniest war of all: Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The president campaigned on a promise that peace could be brokered in just 24 hours. Even Hillary Clinton, once Mr Trump’s arch-nemesis, says delivering a deal that doesn’t involve Ukraine making fresh land concessions would be worthy of the prize.

This presents an opportunity for Europe. The American president has at times seemed bored by the war in Ukraine. After a quick deal proved elusive, he appeared ready to dismiss the conflict as “Biden’s war” and move on. If the shimmering mirage of the Nobel can repurpose his messianic vanity towards greater engagement, so much the better. Europeans hope a newly invested Mr Trump will come to realise that Russia is in fact the obstacle to a realistic deal—and thus to Mr Trump’s white-tailed trip to Oslo.

There are downsides to Mr Trump’s Nobel lust. His get-peace-quick schemes might come at the expense of the tiresome legwork needed to stop the fighting for good. Mr Trump, never a man for details, will instinctively seek the headline of an ended war, leaving Vladimir Putin in charge of the fine print. But a mere photo-op in the Rose Garden won’t do for Mr Zelensky. Above all he needs security guarantees America would have to at least support, but the offer of which remains infuriatingly vague. If talks drag on, as no doubt they will, Mr Trump may find it easier to push Ukraine to accept a shoddy peace than to force Russia into a durable one.

Truce or dare

Beyond his pining for a gold medal, Mr Trump seems to genuinely loathe wars (and has joked that ending them may be his way into heaven). If nothing else, Trump-as-peacemaker is more pleasant to deal with. European leaders visiting the White House received obsequious praise from the president, in contrast to past encounters. Will that endure after October 10th, once the peace prize is bestowed, inevitably to someone else? For Charlemagne will happily wager there are no sane Norwegians who would plump for Mr Trump to receive any prize, let alone one for peace. The man has, after all, threatened to invade countries, slashed American foreign aid and deployed troops in his own capital.

If it is not in European leaders’ gift to get Mr Trump the Nobel, they should do the next best thing: loudly proclaim they are backing Mr Trump for the prize, with letters of endorsement to boot, and drop hints of “Oslo having been spoken to”. Such nominations have zero value; well over 100,000 worthies, including history professors at fourth-tier universities, can put forward whomever they choose for consideration. Several hundred make the cut each year; even Adolf Hitler, of all people, was nominated once. But the gesture will go down well in Mar-a-Lago. If Europe can find a way to channel Mr Trump’s prize-winning delusions to its advantage, a little Nobel tomfoolery may be worth it. ■

International | The Telegram

Was globalisation ever a meritocracy?

The Trumpian assault on globalism, as seen from Singapore

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Aug 19th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

WHEN a schoolyard is taken over by bullies, what are model pupils to do? Something like that quandary is now playing out in the global economy. Since returning to power in January, President Donald Trump has treated trade partners with the swaggering cruelty of a sixth-form tyrant. This marks a change from his first presidency, when American officials acted as harsh disciplinarians. Back then, Trump aides called countries cheats for running trade surpluses with America. They demanded structural reforms from countries like China, accused of stealing American jobs and technologies by abusing world trade rules.

In the second age of Trump, rules are out and the boss’s whim is in. No country has been spared tariffs, even those that run trade balances in America’s favour. This arm-twisting era is ghastly for many governments. It is painful in a special way for high-achieving countries that top league tables for competitiveness or ease of doing business. For such star pupils, late-20th-century globalisation felt like a form of meritocracy. Hard work and wise planning could give an ambitious nation a chance to find its niche in the global economy, transforming its fortunes. Now, over-achieving governments are realising that the old economic order has gone. In its place, they fear a fragmented and inefficient world economy, in which investments and supply chains are guided by politically motivated tariffs and geopolitical rivalries, or Trumpian caprice.

Some of the clearest thinking about this swot’s predicament can be heard in Singapore, a paternalist city-state that has risen from poverty to great wealth with the help of hard work, diligence and lots of rules about civilised behaviour—like a giant prep school with its own army and airport. The Telegram recently travelled there to meet government officials as they celebrated their republic’s 60th birthday in a very Singapore-ish way, with policy conferences and leaders’ speeches about the global order.

Singaporean elites sound anxious and disappointed. Their country set out to be the meritocrats’ meritocracy. Over six decades Singapore drained swamps and cleared slums to create a squeaky-clean, multicultural showcase of skyscrapers and social-housing towers, container ports and high-tech industrial parks, governed by graduates from the finest universities on earth. When older industries declined, Singapore “upskilled”, investing in such sectors as biomedicine and advanced gas-turbine maintenance. Those thrived alongside large financial and services firms.

During the first Trump presidency, Singapore’s elites feared historical forces beyond their control as tensions between their two most important partners, America and China, threatened to divide the world into ideological and economic blocs. Today Singapore’s technocrats sense that, in Mr Trump’s second presidency, the risks of the world economy splitting in two are abating. Instead of grand geopolitical divisions they find themselves worrying about small, even squalid factors affecting business decisions.

America’s president seems bent on undermining merit as a driver of investments, and replacing it with cronyism. In his version of globalisation, countries can buy favour with showy offers to spend billions on factories in Trump-voting states. Other governments have offered murky cryptocurrency deals to members of the president’s family and inner circle. In South-East Asia, Singapore’s backyard, countries that could co-operate to promote regional trade are instead vying to attract trade diverted from neighbours facing higher American tariffs.

Singapore’s prime minister, Lawrence Wong, warned citizens to brace for turbulence at a national-day rally on August 17th. “For decades, Singapore benefited from an American-led rules-based global order. It was not perfect. But it brought peace and stability to the world. And because the rules applied to all, even a small city-state like ours could compete fairly,” he declared. Today, America is pulling back and weakening multilateral systems, undermining old rules and norms and encouraging more countries to chase “narrow, immediate gains over shared progress”, he added.

In late July the deputy prime minister and trade minister, Gan Kim Yong, addressed a policy conference in Singapore straight after returning from a visit to Washington. American officials were “non-committal” when asked if Singapore’s baseline tariff of 10% might rise in the future, Mr Gan told the audience of business people, technocrats, scholars and students. He admitted to “significant uncertainty” about sector-specific tariffs that America is preparing to impose on semiconductors and pharmaceuticals, which are big business in Singapore. Nor could Mr Gan offer clarity about the investments that Japan, the European Union and others have offered to make in America, and whether those funds might be “diverted” from planned investments into Singapore.

Meritocracies are impressive, but not always loved

Singapore is not ready to give up on globalisation. The law of comparative advantage is “extremely difficult to dislodge”, a former central bank chief, Ravi Menon, told the same conference. “Like water in nature, trade finds a way,” he said. Mr Menon blamed much of the current backlash against globalisation on other governments that had failed to retrain their workforces and to spread the benefits of prosperity widely across their societies. By contrast Singapore was called an example of good governance, along with such countries as Switzerland and Denmark. Some say Singapore is boring, said the prime minister, Mr Wong. “But at the same time we are stable, we are predictable.” Being trusted is an asset “others would die to have”, he added.

Singapore does not want to alter its ways. Alas, the schoolyard offers a last lesson. If bullies are rarely loved, the same often holds for model pupils. Only a broad coalition of countries can save globalisation from Mr Trump. Elite over-achievers alone cannot. ■

Business | Schumpeter

American tech’s split personalities

Publicly traded startups aren’t what they used to be

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Aug 21st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

IF INVESTORS IN America’s technology industry had a single mind, it would be in the midst of a dissociative episode. The logical left brain is beginning to wonder if the artificial-intelligence (AI) revolution is all it is cracked up to be. Nuh-uh, retorts the emotional right brain.

The mind’s rational hemisphere is responsible for a wobble on August 19th in the tech-heavy Nasdaq index. This shaved nearly 10% from the market capitalisation of Palantir, an AI-analytics darling worth some $370bn. Nvidia, the AI era’s chipmaker of choice, which last month became the first company in history to be worth over $4trn, saw more than $150bn in shareholder value evaporate. Days before, early backers of CoreWeave cashed in $1bn-worth of shares in the AI-data-centre operator the moment they were allowed to following its initial public offering (IPO) in March. In a vote of confidence, so did one of the company’s directors. CoreWeave’s market value fell by over a third.

This burst of caution in public markets stands in contrast to the unrelenting right-brain exuberance in private ones. Venture capitalists are falling over themselves to back any startup with a dream and AI in its pitch. Even as investors were dumping Palantir shares, Databricks, which also peddles AI analytics, said it was raising fresh capital at a valuation of $100bn, up from $62bn in its previous funding round less than a year ago. The same day the New York Times reported that OpenAI was in talks to let current and former employees offload some of their stakes at a valuation of $500bn, $200bn more than in March—never mind that the ChatGPT-maker’s long-awaited new model proved ho-hum.

You should never read too much into short-term market swings. Despite the latest thud, public tech valuations look dizzying. Private ones are too opaque to draw definitive conclusions. Still, you can read a little bit. And by the looks of it, investors as a group are cooling in their enthusiasm for what is (incumbent tech stocks) while displaying a superheated zeal for what will be (the startups that may one day eclipse them).

The idea that the new must be better than the old is, obviously, itself nothing novel. Yet a look at the past few decades of American tech suggests it may also be increasingly ahistorical. As a group, earlier vintages of startups outmatch newer ones on some key measures of performance. At least that appears to be the case for those firms which decide to subject themselves to the scrutiny of public markets.

Jay Ritter of the University of Florida maintains perhaps the most comprehensive database out there of American IPOs, going back to 1980. At Schumpeter’s request, he crunched the numbers for four IPO cohorts. Call them, loosely, pre-dotcom (1990-98), dotcom (1999-2000), web 2.0 (2001-11) and new web (2012-23).

The first thing to note is that startups of yore were readier to go public than today’s lot. More than 1,200 listed their shares between 1990 and 1998. Another 631 piled in amid the dotcom mania, when basically all you needed for a listing was a domain name. The web 2.0 and new-web generations added just 381 and 485, respectively. As much as your Gen-X columnist would love to blame this on Millennial and Gen-Z founders’ congenital incapacity to endure the harsh discipline of a stockmarket listing, it probably has more to do with the growth of venture capital. This lets startups stay private for longer, which also explains why the typical age at which firms list has risen, from eight years among the pre-dotcoms to 11 for the new-webbers. (On this and subsequent measures, the dotcom folly led to such outlier results that it makes sense to exclude them for the analysis.)

Being older, the more recent vintages were also bigger. The typical new-webber went public having generated $191m in the previous 12 months, four times the figure for its pre-dotcom forebear after adjusting for inflation. A rougher analysis than Mr Ritter’s of the 1,000 biggest tech firms in the Nasdaq implies that post-IPO sales also grew more slowly from this higher base. Newer vintages are also likelier to be lossmaking. Whereas 60% of the pre-dotcoms were making money when they listed their shares, the same is true of just 24% of new-webbers. The web 2.0 group sat in between, with 40% being profitable.

One consequence of being worse at making money is being better at going belly-up. Less than 6% of the pre-dotcoms found themselves in distress within three years of IPO (which Mr Ritter defines as a 90% decline relative to the offer price or a delisting). This rises to 7% for web 2.0 and 11% for the new web. Admittedly, things even out five years after a listing: 14% of the pre-dotcoms and 12% of the new-webbers were in trouble by then. But other things being equal, you would expect the share to be higher for the earlier vintages, which had less time to test their business models.

Head-scratcher

And still, investors’ novelty fetish seems intact. The average new-web firm outperformed the market in terms of shareholder returns (including dividends) by a cumulative 52 percentage points over its first five years as a public company, according to Mr Ritter’s sums. The pre-dotcoms and web 2.0 managed 41 and 15 points, respectively. For web 2.0 and especially the new web, this outperformance was driven by larger startups; those with pre-IPO sales below $100m barely beat the benchmark.

Investors are, in other words, rewarding newness and bigness rather than quality. Mr Ritter finds virtually no difference between the returns afforded to profitable and unprofitable tech businesses in the years after their IPOs. If startups with sounder fundamentals cannot count on outsize gains in the stockmarket, more may opt to stay private. The result could be a cycle of adverse selection. Something for the left brain to ponder. ■

Business | Bartleby

The last days of brainstorming

Enjoy the peculiar melange of whiteboards and humans while you can

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Aug 21st 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

Alan: Let’s get going. We’ve all had a chance to think of some fresh names for our new value-added membership service. The last time we met we talked about calling it Gold or Platinum: if it works for the likes of American Express and Virgin Atlantic, it can work for us. But some of you felt that we could be more original. So let’s write our favourite ideas on the whiteboards, and then we’ll review them. We want a shortlist of three for Peter to choose from.

[Sound of breathing and writing.]

Alan: OK. Let’s take a look and see if any themes emerge. I can see a few metals and minerals here. Iridium. Osmium. What’s Californium?

Michaela: I put that down. It’s the most expensive metal.

Walter: It’s also highly radioactive.

Michaela: Oh.

Alan: This says Platinum again.

Sally: That was me.

Alan: Weren’t you listening at the start? And who are you?

Sally: I’m really sorry. I’m actually in the wrong meeting and was checking my phone for the right location when you were talking. And then I felt like it was too late to leave. I’ll go now. [Sound of chair scraping, footsteps, door closing.]

Alan: Let’s just take another one. Rolls-Royce. Who was that?

Rupert: That’s mine. I was thinking that we should use a brand that is synonymous with quality.

Violet: Oughtn’t that to be our own brand? Especially since we are also in the automotive industry.

Alan: What does this say? It’s almost completely illegible.

Shreya: Celine Dion.

Alan: Oh.

Shreya: I was thinking of people who sell out their shows, you know. So it’s hard to get into.

Jon: I get it. So people with residencies in Las Vegas. Like Adele. Or those magicians with the tiger.

Rupert: Calvin and Hobbes?

Jon: Yes, that’s them.

Violet: I’m not sure. Isn’t a bit weird to say “I’m in Celine Dion”?

Alan: What’s this one?

Michaela: Yttrium. It’s a rare earth.

Rupert: Metals again?

Michaela: Says the man who wants to use another brand name to signal quality.

Alan: I like the idea but it’s a bit unpronounceable. Let’s look at a couple more. Praseodymium. I assume that’s you again, Michaela. And Gucci is presumably you, Rupert? How about this one. Oxygen?

Jon: That was me, but I now see that it’s better for our basic service. Sorry.

Alan: And this one?

Kate: Jeroboam. I thought maybe we should use units associated with a very special occasion.

Walter: A Jeroboam is not that big. The biggest bottle is a Melchizedek.

Alan: Not sure that we want to be too closely associated with alcohol, given we’re in the business of car rentals. What’s this one? It looks like “Inspire”.

Violet: That was left over from the previous meeting.

Alan: Nice. Not many left. Everest?

Rupert: That implies huge effort, extreme cold and a high risk of death.

Michaela: You should go.

Kate: What about Alcove? I just love that word. Doesn’t it sound like a winter evening reading a book?

Alan: Which would be great if we were selling winter evenings. Is there a nice word that conjures up renting cars?

Kate: Freedom?

Jon: Wheels?

[Door opens]

Alan: You again? We’re not done.

Sally: I’m sorry. My other meeting is over and I just wanted to suggest another one. Elara.

Walter: The moon of Jupiter?

Sally: Yes. I saw you were still going, so I asked ChatGPT for ideas. It honed the list, worked up some taglines and did a trademark search. This one jumped out. I quite like Zenith and Regent, too.

Violet: I like Elara.

Rupert: As long as Michaela didn’t suggest it, I’m OK with that.

Michaela: If Rupert likes it, I’m against it.

Alan: We’re going to have to wrap up. I’ll take Elara and Inspire to Peter. But he’s a massive Celine Dion fan, so we may well have a winner.■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

In praise of complicated investing strategies

To understand markets, forget Occam’s razor

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Aug 18th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

Occam’s Razor is a cornerstone of the social sciences, and for financial economists it is almost an article of faith. The principle is named after William of Ockham, a 14th-century monk. It holds that the simplest explanation for any phenomenon is the best. Financial analysts today live in fear of “overfitting”: producing a model that, by dint of its complexity, maps onto existing data well, while predicting the future poorly. Now, though, Ockham is on trial. New research suggests that, when it comes to big machine-learning models, parsimony is overrated and complexity might be king. If that is true, the methods of modern investing will be upended.

The debate began in 2021, when Bryan Kelly and Kangying Zhou of Yale University, and Semyon Malamud of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, published “The Virtue of Complexity in Return Prediction”. In one exercise, Mr Kelly and his co-authors analysed just 12 months of data using a model with 12,000 separate “parameters”, or settings. Using so many of them—the opposite of what Occam’s razor prescribes—would traditionally have been thought to raise the risk of overfitting. Yet the complexity in fact seemed to help the model forecast the future. Might Occam’s razor, the paper’s authors asked, be Occam’s blunder?

It is an academic debate, but the outcome will have sweeping consequences. Mr Kelly is also a portfolio manager at AQR, a quantitative hedge fund. The firm was once known for using more traditional—and parsimonious—methods than its peers. But it is now embracing the apparent virtues of complexity. Researchers, worried about overfitting data, have worried too little about underfitting it, reckons Mr Kelly.

Making better predictions with small data sets could be enormously profitable. Much financial research is strangled by small sample sizes and the difficulty of conducting experiments. Gathering more data often requires waiting, and in some areas it is incredibly sparse. When studying extreme events such as market blow-ups, bank runs and sovereign defaults, researchers often have just a few examples in modern history. Hedge funds in search of an edge spend billions of dollars on alternative data, from satellite images of Chinese rail traffic to investor sentiment scraped from social media.

Recently, the debate over complexity has reached fever pitch. Mr Kelly and his co-authors have faced a barrage of scepticism. Álvaro Cartea, Qi Jin and Yuantao Shi, all of the University of Oxford, suggest the virtues of complexity may not hold if the data used is poorly collected, erroneous or otherwise noisy. Stefan Nagel of the University of Chicago suggests that for very small data sets, the complex models actually mimic a momentum-trading strategy, and that their success is a “lucky coincidence”. Messrs Kelly and Malamud have responded to their respondents with another detailed paper.

It is too soon to prepare a eulogy for Ockham’s maxim. But even the sceptics do not outright reject the idea that big, complex models can produce better forecasts than simpler ones—they just think this might not be true at all times. Meanwhile, if the virtues of complexity are real, the changes to how many investors operate could be immense. Hiring the best machine-learning engineers will be more important than ever, and so, if Mr Cartea and his co-authors are correct, will acquiring and cleaning data. The billion-dollar pay packets that tech firms offer superstar coders may begin to pop up at investment firms, too.

Investment firms will also see greater benefits from scale. The computational power required to train and run models is expensive, and thus may become a “moat” protecting large hedge funds from competition. Larger players will be able to afford to experiment more, and across a wider range of asset classes. Smaller rivals may struggle to keep up.

Reduced competition is not the only risk. Humans are still catching up when it comes to working out what the most advanced machine-learning models are doing. Investors may become increasingly reliant on black-box algorithms that are extremely difficult to interpret. Small models benefit from being not only easy to deploy, but easy for investors to think about, and to tweak. Few will complain so long as they are making money. Yet if anything goes wrong with the new models—ranging from mundane underperformance to entire investment strategies blowing up—their fans may find themselves wishing for a tool that could cut through the complexity. ■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

Economists disagree about everything. Don’t they?

Their discipline is famous for its fissiparousness

Illustration: Alvaro Bernis

Aug 21st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

When President Donald Trump fired Erika McEntarfer, America’s labour statistician, he achieved something supposedly rare: he got economists to unite. In a survey by the University of Chicago’s Clark Centre for Global Markets, 100% of the discipline’s most prominent practitioners agreed that there was no evidence the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) was biased.

Over history, economists have disagreed a lot. The 18th century saw classical types spar with mercantilists; the mid-20th pitted Keynesians against monetarists. More recent decades have set champions of rational expectations and efficient markets against behavioralists. Sometimes disputes remain cloistered in academia; often they spill into the public square, in arguments over minimum wages, debt sustainability and monetary-policy rules.

George Bernard Shaw is said to have joked that if all economists were laid end to end, they still would not reach a conclusion. Winston Churchill suggested that, if you wanted two opinions on a matter, you should put two economists in a room. The Trump era, however, has ushered in seemingly unprecedented unity. Each new White House directive invites the collective ire of a profession famous for its fissiparousness.

Since 2011 the Clark Centre has polled economists on topical issues such as cryptocurrencies, fracking and inequality. Some questions, such as that about the BLS survey, might seem straightfoward; others are trickier. Recent surveys have asked about the effectiveness of sanctions on Russia, if foreign aid can raise GDP growth and whether climate change threatens financial stability. And although Mr Trump has inspired consensus on a number of issues, even before his arrival economists were more united than their caricature suggests. On over a quarter of questions, respondents who register an opinion in one direction lean the same way as the others; on most, more than nine in ten are like-minded.

In almost every question on trade policy—be it about NAFTA or whether commerce with China has left Americans better off—economists defend free trade. None of them agrees with the statement that “higher import duties…to encourage producers to make [in America]…would be a good idea”; only a handful think such tools can even substantially affect the trade deficit. Taxes are another hot-button issue that elicit less controversy than might be expected. Pigouvian taxes are popular; Laffer curves are not. Few economists thought that extending tax cuts from Mr Trump’s first term would meaningfully boost GDP; most agree that restoring the top marginal rate to 39.6% would not impede growth.

The list of agreed-upon statements does often read like a catalogue of presidential rebukes: vaccine refusal imposes externalities; politicising monetary policy is folly; sovereign-wealth funds and strategic crypto reserves serve little purpose; bans on high-skilled immigration would sap America’s research-and-development leadership, push businesses abroad, hurt average workers and do little to boost employment.

A Trump supporter might survey this scene and reach an obvious conclusion: that economics is less a science than a guild dominated by conformist elites. But although many economists have an instinctive dislike of the president, such a charge cannot explain why the panel is equally sceptical of traditionally left-wing policies, like interest-rate caps and rent control, as of right-wing policies, like self-financing tax cuts. Or why experts are as likely to agree that “rising inequality is straining the health of liberal democracy” as they are to disagree with Thomas Piketty’s claim that the blame for this lies with the fact that returns on capital are rising faster than economic growth. There is, to be sure, shared respect for free markets, but one that is nuanced enough to accommodate support for bank bail-outs and congestion pricing.

That is why the disagreements revealed by the Clark Centre’s survey are more telling than the consensus. Antitrust is one fault line. Economists are split on whether American airline mergers should have been approved, whether big tech platforms ought to be broken up and whether artificial-intelligence firms merit scrutiny. Financial regulation is another. Economists broadly agree that oversight is required, including of the non-bank intermediaries that now make up much of the financial system. But ask what optimal regulation would look like and dissent quickly emerges. Would Americans be better off if the size of banks was capped at 4% of the industry’s assets? Should America increase the deposit insurance available to customers? On these questions, no more than 60% of experts populate a side.

Up in the air

What do antitrust and regulation share that tariffs and migration do not? Part of the answer concerns the nature of the trade-offs. Antitrust weighs the costs of market power against efficiencies of scale; financial regulation pits stability against growth. By contrast, the net effects of free trade or high-skilled immigration are clearer. On trade and migration there are reams of evidence across countries and decades. Antitrust cases and financial crises are rare, idiosyncratic and hard to generalise about. Thus it is easier to gauge the effects of a tariff than to know what would have happened had a bank run been allowed to proceed. Economists, in the end, can be only as confident as the data let them be.

This leads to the last category of interest from the Clark Centre’s polls: those questions on which economists report great uncertainty. If there is a common thread here, it is novelty. Will AI lead to larger increases in GDP per person than did the internet? Will stablecoins account for a substantial share of payment flows in ten years’ time? Does the growth of private credit raise systemic financial risk? Economists may be willing to take on the president; they are less willing to take a punt on the future. ■

Science & technology | Well informed

Should you use a standing desk?

The benefits are real, but seem to vary with age

Illustration: Fortunate Joaquin

Aug 15th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

THE HUMAN body evolved to forage and hunt on the African savannahs, not to sit in a cubicle all day. The risks associated with sitting—from increased blood-sugar levels to greater odds of dying from cancer—lead many health authorities to warn against spending too much time doing so. The sit-to-stand desk is a popular way of helping people get upright. But how effective is it?

Several arguments are made in its favour. As standing makes the heart work harder, proponents say it improves cardiovascular health, enhances attention and reduces fatigue. Physiotherapists claim that standing also improves posture, reducing lower back pain. Some studies even suggest that standing workers report lower stress and greater happiness than sitters do.

Dozens of studies have been run on the potential health effects of sit-stand desks. A recent review, led by María Eugenia Visier-Alfonso at University of Castilla-La Mancha in Spain and published in BMC Public Health in May, selected 17 for examination. Dr Visier-Alfonso limited her analysis to those that looked mainly at university students.

Of the four studies that looked at mental health, three confirmed that sit-stand desk use reduced anxiety and improved mood. Of the four on back pain, however, only one revealed significant pain reduction among sit-stand desk users compared with control groups. The one study Dr Visier-Alfonso found that looked at the cardiovascular and metabolic benefits of sit-stand desks suggested that they do result in users having lower blood pressure. (The remainder mostly looked at academic outcomes, which were mixed.)

Studies conducted on more varied groups reach different conclusions. A general review of over 50 papers on sit-stand desk use, led by April Chambers at the University of Pittsburgh and published in Applied Ergonomics in 2019, found only weak evidence that their use improves cardiovascular health.

The heart rates of sit-stand desk users were 7.5-13.7 beats per minute faster on average than those of people at ordinary desks, indicating that they might be working harder. But the studies that examined the question found no notable differences in blood pressure or VO2 (the efficiency with which the body transports oxygen to the muscles).

Analysis of other health-related biomarkers, like glucose, insulin and cholesterol, were also no different in most studies. This suggested that the desks were not providing metabolic benefits that might, say, stave off diseases like type 2 diabetes. Improvements in levels of energy and attention among those who used sit-stand desks were similarly difficult to spot. What’s more, Dr Chambers found no evidence that their use influenced mood.

However, notable benefits did emerge in the area of lower-back pain. Of 17 papers that studied this question, eight revealed evidence that giving participants the option to stand significantly reduced their lower-back pain (the remaining nine showed no clear effect). This suggests that standing may help some people with this condition, an effect that may be more noticeable among people past university age.

So what is the aching desk jockey to do? Both reviews agree that no significant harm is associated with the use of sit-stand desks. And although some of the differences between their conclusions may stem from chance or sample size, it is also possible that different benefits accrue to users of different ages. ■

Culture | Drugs and religiosity

High priests: why scientists gave magic mushrooms to the clergy

An experiment looked at how religious folk responded to psychedelic drugs

Illustration: Cristina Daura

Aug 21st 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

SOME PEOPLE think of their hounds as heavenly, sporting T-shirts proclaiming that “‘Dog’ is ‘God’ spelled backwards.” For Jeff Vidt, God actually was a dog: the Lord came to him as a Great Dane. Meanwhile, Jaime Clark-Soles glimpsed the deity as a harp-playing woman. Sughra Ahmed felt the Almighty as a concept: love.

These divine encounters occurred at Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, during an experimental study investigating how “the effects of psilocybin”—the active ingredient in magic mushrooms—“are experienced and interpreted by religious clergy”. The 29 participants came from Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and Judaism and were “psychedelic-naive”: ie, they had never dabbled in these drugs before. They took psilocybin on two occasions; there was a waiting-list control group.

The sample size may be small, but the findings, recently published in the Journal of Psychedelic Medicine, are mighty clear: 96% of participants ranked a psilocybin trip in the top five most spiritually significant moments of their lives and 42% declared it the single most profound experience they had ever had. (A recent study in Sweden also found that 58% of people found a psychedelic experience to be one of the most meaningful events of their lives.) Almost half described their trips as “psychologically challenging”, but none reported severely adverse effects.

Psychedelics change the way the default mode network (DMN) in the brain works. These linked parts of the brain are activated when people muse on the past, present or heavenly future. Psychedelics switch some of the DMN off at the same time as they activate other neural pathways, all of which allows for new ways of thinking. Scientists are exploring how psilocybin may help treat depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

More than a year after the study, participants reported a deeper connection to their faith and improved prayer. Hunt Priest, an Episcopalian, felt an electric current in his spine; it stopped at his throat before exploding out of his head. The blockage was “connected to my preaching”: “I felt restricted in what I could say.” He has “never thought of the Holy Spirit the same again”. Roger Joslin, also an Episcopalian, says: “There’s my life before psychedelics and my life afterwards.”

Yet such spirituality is unlikely to please traditionalists, who argue that true faith is the product of discipline, not mind-bending drugs. Some may worry that these experiences threaten religious institutions: who would rather sit in a dusty pew than fly with the angels? As Mr Vidt, an Anglican priest, put it: “I don’t believe in God: I know God. I experienced God.”

Psilocybin also seems to promote the kind of universalism that religious authorities have spent centuries trying to contain. Mr Priest says he prayed as a Jew, then a Muslim; Julie Danan, a rabbi, chanted “Shalom” next to Hindus saying “Om”. “It’s hard to imagine having a psychedelic experience that made someone more narrow or exclusionary in their faith,” says Mr Joslin. “It’s likely to broaden it.” This may bother religious authorities who must advance their own faith as superior to others.

Advocates argue that drugs are a conduit to the sorts of mystical things that are described in scripture, such as multi-headed beasts. “The whole Book of Revelation is a visionary journey,” says Ms Clark-Soles, a Baptist minister. “Christianity is fundamentally based on a mystical experience: the resurrection of a dead guy.”

Ms Clark-Soles is writing a book called “Psychedelics and Soul Care: What Christians Need to Know”. Several of the study’s participants have set up organisations aimed at exploring the benefits psilocybin can offer believers. Mr Priest established Ligare, a “Christian psychedelic society”; Zac Kamenetz, a rabbi, launched Shefa to support Jews; Ms Ahmed, an imam, created Ruhani for Muslims. Some feel the Religious Freedom Act should protect institutions in America offering drugs for spiritual purposes. Talk about a higher calling. ■

Obituary | The most beautiful man in the world

Terence Stamp preferred philosophy to celebrity

The film face of the 1960s died on August 17th, aged 87

Photograph: Getty Images

Aug 21st 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

As he stood on his mark, sunshine fell softly on his blond curls. Around him, beyond the deck of HMS Avenger, the waves sparkled. Beside him, in a slight breeze, the noose swayed. Sometimes it touched his face. Mutinous sailors thronged the lower deck, watching. He, Billy Budd, a saintly young crewman, was about to be unjustly hanged. And he was at peace, the script said.

How could he play a scene like that? He struggled to remember what Anthony Newley, another working-class actor like him, had told him. Empty head. Get rid of all the thoughts. He couldn’t do it; they kept coming. But then, suddenly, a song popped up from nowhere: “Little Dolly Daydream, pride of Idaho...” and he was full of another feeling. Lying on a rug in front of a coal fire at his Granny Kate’s house in Barking Road, doing his homework, while out in the scullery she would be making him a marmalade sandwich and singing. This was a feeling beyond thinking, a strange otherness, and at the premiere of “Billy Budd” in 1962, it left not a dry eye in the house. He had nailed it in one take.

That film shot Terence Stamp to fame, winning him at 24 an Oscar nomination. After that it was a film a year: “The Collector” (a psychopathic butterfly collector pinning down Samantha Eggar), “Modesty Blaise” (a Cockney sidekick to a comic-book heroine), “Far From the Madding Crowd” (arch-cad Sergeant Troy ensnaring Bathsheba), “Poor Cow” (a bank robber with a tender side). He became one of the icons of the 1960s, all wide eyes and good cheekbones, and one of the voices too, confidently Cockney. His girlfriends were Jean Shrimpton and Julie Christie, both epitomes of class and style. David Bailey photographed him. He filmed in America, smoking peyote and a lot of Acapulco Gold. He worked with William Wyler and John Schlesinger. Best of all, in 1968 Federico Fellini chose him as his leading man.

It was all a bit surprising really. He didn’t actually think he looked that good. Clothes were fun, and he had always been mad about them, dragging his mum all over the market looking for the right jacket, dreaming of custom-made shoes. But his face? “The most beautiful man in the world” was mostly the creation of the lighting designer on “Billy Budd”, Robert Krasker, who had lit “The Third Man”. Film could do that. And this was something he had known ever since he was three, sitting with his mum in the one-and-ninepenny seats at the Old Grand and watching Gary Cooper play Beau Geste: cinema was magic.

People often thought there was something magical about him, too. Or, at least, intensely strange. Or mesmerising, like the terrifying sabre-whirling display he put on for Julie Christie in “Far From the Madding Crowd”. (All the scarier because he, a leftie, was made to do them right-handed.) Brooding silences were also his speciality. The thing was, he was fascinated by acting and how it was done well. In “Billy Budd” he had sent his feelings directly to the audience without needing words. Their minds had met in a sort of empty but conscious space. And what this had seemed to require from him was to be absolutely present in the moment. Not observing his thoughts, not worrying about direction, but giving his purest self to the audience and bringing out the best in them.

As an acting method, though, it was hard to achieve. He began to consider it seriously when in 1968 he met Jiddu Krishnamurti in Rome and went for a walk with him. Krishnamurti would keep interrupting their chat to point out a tree, or a cloud. To an East End spiv like him, that seemed weird. Later he realised that if he had not noticed them too, it was because he was not yet fully in the moment. That was what he had to work on. His longest attempt so far, in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Teorema” (1968), was to play a divine stranger who seduced an entire family as pure consciousness and energy. Because he had no lines, he simply was.

In 1970 he went off to India, less to study than because, in a new decade, directors wanted a younger face than his. Over seven years in an ashram in Poona, in orange robes and on a macrobiotic diet, he took up yoga and meditation and picked up advice on breathing from Sufis he met. Yet a cable mentioning a role in Superman, and the chance of working with Marlon Brando, got him home and in the part in a trice, robes, beard and all. He needed no preparation. He was awake now, and thought, I’ll just go with that.