The Economist Articles for Sep. 1st week : Sep. 7th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.08.29조회수80 목록 댓글 0The Economist Articles for Sep. 1st week : Sep. 7th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | America’s blunder

Humiliation, vindication—and a giant test for India

Trump has triggered a trade and defence crisis: how should Modi respond?

Aug 27th 2025|5 min read

IT IS UNUSUAL to experience humiliation, vindication and a defining test all at the same time. But that is India’s predicament today. President Donald Trump has undone 25 years of diplomacy by embracing Pakistan after its conflict with India in May, and now singling out India for even higher tariffs than China. He cannot have thought through how the world’s most populous country and fifth-largest economy would react.

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, recently laid out a path for a muscular, more self-reliant nation. He is also about to meet Xi Jinping in China, after a bitter four-year Sino-Indian military stand-off in the Himalayas. For America to alienate India is a grave mistake. For India it is a moment of opportunity: a defining test of its claim to be a superpower-in-waiting.

Mr Trump’s humiliation of India comes in two flavours. On August 27th, after condemning it for buying Russian oil, America’s president imposed a 25% tariff surcharge, on top of the existing 25% import tariff on Indian goods. Buying Kremlin crude is grubby. But given that India does so through a price-cap scheme run by the West, that it sells refined petroleum products to Europe, and that much of the world, including China, also buys Russian oil, the surcharge makes it look as if India has been singled out for special punishment.

The other humiliation is Mr Trump’s love-in with Pakistan. After a terrorist attack in India that Mr Modi blamed on Pakistan, the two rivals fought a four-day skirmish in May, involving over 100 warplanes and raising fears of a nuclear clash. Yet Mr Trump is now exploring crypto and mining deals in Pakistan. He has dined in the White House with Field-Marshal Asim Munir, its hardline army boss and de facto ruler, who is proposing Mr Trump for a Nobel peace prize. America has offered to mediate over disputed Kashmir, breaking its own long-standing position and an Indian taboo.

America’s failure to support India on a core security interest and decision to punish it over trade have shattered trust among Indians. Since 2004 American presidents have welcomed India as a rising democratic power opposed to Chinese domination of Asia. Its $4trn economy and $5trn stockmarket dwarf those of Pakistan, wracked by instability, debt crises, terrorism and dependence on China. This is a giant own-goal for America’s interests that compounds its neglect of NATO in Europe.

That explains the second emotion among some in India: vindication. Since independence in 1947, India has avoided alliances, although the label it uses has changed from “non-alignment” to “multi-alignment”. It relies on Russia for some weapons, and on Europe, Israel and America for others. China supplies manufacturing inputs; the West tech and markets.

In 2020, however, when relations with China went into a deep freeze after the border skirmishes in the Himalayas, some in Washington hoped this might presage a quasi-alliance with America. Intelligence has been shared, and joint US-India military exercises, which also included Japan and Australia, led to a strategic deal in 2024 on closer defence ties.

Indians sceptical of global entanglements feel vindicated by the events of the past few months. As they always warned, dependence on America is dangerous. Mr Modi’s visit to China is meant to signal that India has options.

Humiliation and vindication pose a test of India’s capabilities and resilience. For 11 years Mr Modi has pursued nation-building, modernisation and centralisation. There have been setbacks. An industrialisation drive has had modest results and failed to produce the new jobs India needs. The education system is poor. Mr Modi often lapses into Hindu chauvinism.

But there have also been successes. New roads and airports, and digital payments and tax platforms, have created a giant single market. The financial system is stronger, with deep capital markets built on domestic savings, a nearly balanced current account and prudent banks. India is now less likely to attract supply chains as part of a “China plus one” boom, but all this will help it weather the trade shock. Growth is expected to remain above 6%, making it the world’s most dynamic big economy and, the IMF says, its third-biggest by 2028.

The danger is that America’s aggression revives slumbering autarky and anti-Westernism. In his Independence Day speech from the Red Fort in Delhi on August 15th, Mr Modi emphasised more self-reliance. But were India to go further and turn inwards, it would threaten its services industry, which now exports almost as much as all other sectors put together. Its tech-services firms make at least half their sales to American customers, including blue-chip firms with “global capability centres” in India. The country is OpenAI’s second-biggest market by users. And to industrialise faster, India needs more machinery imports and inputs from China.

Better for India to try to limit the damage. It should make rational concessions, including cutting tariffs and buying less Russian oil and more American natural gas. America and India still have enduring bonds, not least a huge diaspora. Mr Modi is right to go to China: boosting India’s manufacturing will mean closer trade links in the next decade, as well as American tech. He should seek new trade deals, adding to recent ones with Britain and the United Arab Emirates.

Look out to look in

A second priority should be reform at home. India’s fate—and its choice—is to be independent. Size and dynamism matter more than ever, to secure better terms in deals, pay for defence and raise living standards even if world trade slows. India has been waiting for several years for more big-bang reforms, including deregulating business, reforming the courts, and modernising agriculture, land and power distribution.

Many of these require co-operation between India’s states and the central government. Encouragingly, Mr Modi has just said he will simplify the goods-and-services tax and deregulate the economy, emphasising “Next Gen Reform”. After 11 years in office, he needs to go further and faster. To confront India’s deepest internal challenges has always been in its national interest. In a hostile world, it is also the best defence. ■

Leaders | The trial of Jair Bolsonaro

Brazil offers America a lesson in democratic maturity

It is a test case for how countries recover from a populist fever

Aug 28th 2025|5 min read

IMAGINE A COUNTRY where a polarising president lost his bid for re-election and refused to accept the result. He declared the ballot rigged and used social media to urge his supporters to rise up. They did so in their thousands, attacking government buildings. Then the insurrection failed, the ex-president faced a criminal investigation and prosecutors put him on trial for plotting a coup.

That sounds like a fantasy of the American left. In the hemisphere’s other giant democracy it is reality. On September 2nd the trial of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s former president and the “Trump of the tropics”, will begin in the Federal Supreme Court. The evidence reads like a flashback to Brazil’s turbulent past. A former four-star general schemed to overturn the result of the election; assassins planned to murder its real winner. As our investigation into the plot explains, the coup failed because of incompetence rather than intent.

Mr Bolsonaro and his associates are likely to be found guilty. That makes Brazil a test case for how countries recover from a populist fever. In Poland, two years after Law and Justice (PiS) lost power, a coalition led by Donald Tusk, a centrist, is constrained by a new PiS president. In Britain, Brexit is now unpopular but Nigel Farage, the politician who inspired it, is leading in polls. Even Hamas’s massacre of October 7th 2023 did not shake Israel out of its bitter divisions.

But Brazil’s most striking comparison is with the United States. The two countries seem to be swapping places. America is becoming more corrupt, protectionist and authoritarian—with Donald Trump this week messing about with the Federal Reserve and threatening Democrat-controlled cities. By contrast, even as the Trump administration punishes Brazil for prosecuting Mr Bolsonaro, the country itself is determined to safeguard and strengthen its democracy.

One reason Brazil promises to be different from other countries is that the memory of dictatorship is still fresh. It restored democracy in 1988. The supreme court, shaped by the “citizens’ constitution” enacted at that time, still sees itself as a bulwark against authoritarianism.

In addition, most Brazilians are open-eyed about what Mr Bolsonaro did. A majority of them believe that he tried to stage a coup to keep himself in power. Conservative state governors vying to take on the leftist president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in next year’s election need the votes of Mr Bolsonaro’s supporters to win. But even they criticise his political style.

That recognition has opened up the chance of reform. As our briefing lays out, most of Brazil’s politicians, on left and right, want to put the Bolsonaro madness and its radical polarisation behind them. From the business bigwigs in São Paulo to the political Pooh-Bahs in Brasília there is surprising agreement on a difficult, but urgent, agenda of institutional change.

Paradoxically, a key task is to rein in the supreme court, despite its role as the guardian of Brazil’s democracy. As the arbiter of a constitution that runs to 65,000 words, the court oversees a dizzying array of rules, rights and obligations, from tax policy to culture and sports. Groups from trade unions to political parties can bring cases directly. Sometimes justices initiate cases themselves, including an inquiry into online threats, some of them against the court itself—making it the victim, prosecutor and judge. To handle a workload of 114,000 rulings in 2024 alone, most decisions come from individual judges. There is wide recognition that unelected judges having so much power can corrode politics, as well as save it from coups. The justices themselves see the case for change.

Fixing the court will be hard, but its power is only part of the constitutional baggage Brazil is carrying. The country also suffers from chronic fiscal incontinence, in particular out-of-control tax exemptions and automatic spending increases. Some of these were enshrined in the constitution of 1988 to constrain would-be authoritarian leaders. Some are the fault of Brazil’s Congress, which has seized control of the federal budget and uses its influence to finance pet projects. The effect is to crowd out investment and weaken growth.

In theory, this points to a path forward. Mr Bolsonaro must be tried for his crimes and punished if found guilty. Next year the election should be fought over the broader reforms.

In practice, none of this will be easy. One obstacle is Mr Trump. He has accused Brazil’s supreme court of a “witch-hunt” against his friend, and in early August slapped 50% tariffs on Brazilian goods. The administration has also imposed Magnitsky sanctions—an exclusion from America’s financial system usually aimed at human-rights abusers and kleptocrats—on Alexandre de Moraes, the judge leading the Bolsonaro case. Other officials and politicians may follow. This recalls an ugly bygone era when the United States habitually destabilised Latin American countries.

Fortunately, Mr Trump’s interference is likely to backfire. Only 13% of Brazil’s exports go to the United States, and they consist largely of commodities, for which new markets can be found. America has already granted numerous exemptions. So far, Mr Trump’s attacks have only strengthened Lula’s standing in opinion polls, and provided him with an excuse for any poor economic news before the next election, in October 2026.

The domestic obstacles to reform are greater. Even if the elites want change, Brazil is still a deeply divided country. Mr Bolsonaro has fanatical supporters who will cause trouble, especially if the court imposes a stiff sentence. Reforming the supreme court and the constitution requires groups to give up power for the common good. It is natural for them to cling to what they have—if only because they do not trust their enemies. Everyone wants growth, but to get more of it some people are going to have to surrender some privileges.

Tensions will therefore be inevitable. But unlike their counterparts in the United States, many of Brazil’s mainstream politicians from all parties want to play by the rules and make progress through reform. Those are the hallmarks of political maturity. Temporarily at least, the role of the Western hemisphere’s democratic adult has moved south. ■

Asia | Banyan

Narendra Modi’s secret weapon: the Indian consumer

Low inflation, tax cuts and falling interest rates will boost an economy hit by tariffs

Illustration: Lan Truong

Aug 28th 2025|4 min read

WHEN IT RAINS it pours. In August some parts of India received as much precipitation in one week as they usually do all month. Delhi, India’s capital, escaped the worst of the weather. But politically, it has been a stormy spell for Narendra Modi, the prime minister.

The month dawned with the government reeling from a 25% tariff announced by President Donald Trump at the end of July, a mere point below the original “reciprocal” rate set out in April. A few days later Mr Trump slapped another 25% on India, purportedly to punish it for buying Russian oil. It was a triple blow for Mr Modi. The 50% rate, which came into force on August 27th, will damage India’s ambitions of growing into an export power. It is a hit, too, to the prime minister’s carefully crafted strongman image. And it is a personal blow for a leader who thought he had cultivated a bond with Mr Trump.

The government is under pressure on the domestic front as well. A hasty revision of the voter list in the eastern state of Bihar, which holds elections later this year, has been criticised by opposition figures as an exercise in disfranchisement. Separately, Rahul Gandhi, the leader of the opposition, pointed to what he called irregularities in last year’s general election and accused the Election Commission of India, a constitutional body, of colluding with the ruling party (which it denies).

Yet for all the gathering clouds, Mr Modi still has reason to feel sunny. Electoral lists in a poor mofussil (or rural) state do not set the public’s pulse racing, and in any case the pro-Modi media have hardly played up the allegations. The humiliation meted out to India by Mr Trump, though harder to gloss, has put Indians’ backs up and allowed the government to reassert its long-standing claim of working to make India “self-reliant”. But it is not just his skill at defensive play that should give Mr Modi cause for cheer. It is that things are looking up in the one place voters care about more than any other: their wallets.

One big reason is inflation. Prices in July rose 1.6% year-on-year, the lowest in eight years. That is partly the result of a good winter harvest, which has kept the price of staples and vegetables low. An ample monsoon and a good summer sowing season suggest the trend may last. Analysts expect inflation to remain subdued well into next year.

A little under half of India’s workforce toils in agriculture. Good harvests are reflected in real agricultural wage growth, which hit an eight-year high of 4.5% year-on-year in May, according to Goldman Sachs, a bank. That in turn spurs consumption in the countryside. The rural economy is showing signs of strength after an anaemic post-pandemic period. Government welfare spending, especially targeted at women, has helped, too.

Falling inflation also creates space for India’s central bank to lower the cost of money. Headline interest rates have fallen one percentage point already this year, and some analysts expect another 0.25% cut by December. Leveraged Indians, especially those with mortgages, now have more money to spend.

The ruling party cannot take credit for the monsoon or rate cuts. But it can for a tax bung aimed at middle-income earners. Starting this financial year, which runs from April, anyone earning up to 1.2m rupees ($13,700) will pay no income tax, a rise from 700,000 rupees. That covers more than 85% of people who file tax returns.

A different tax cut will have even more impact. On August 15th Mr Modi announced a long-overdue reform of India’s goods-and-services tax, to be implemented by Diwali, which this year falls in late October. The tax, introduced in 2017, is an unwieldy mess of four rates. It will be simplified to just two—5% for essentials and 18% for everything else (plus a 40% sin rate for a handful of items). Taxes on everything from shoes to cars are likely to fall.

The combination of lower inflation, interest rates and taxes will boost Indian consumption—which accounts for 61% of GDP. For the government, that will help compensate for the hit the economy takes from American tariffs. And for consumers, talk of electoral lists and declining exports will seem abstract compared with the feel-good factor of buying a new washing machine or dining out somewhere nice.

By Diwali, the monsoon will have receded and the skies will once more be clear. As for being a political weather-maker, voters may just credit Mr Modi for bringing out the sun. ■

China | Purges

Something is amiss in China’s foreign-affairs leadership

Diplomats are disappearing at an extremely busy time

Photograph: Alamy

Aug 28th 2025|2 min read

CHINA’S DIPLOMATS are working hard. On August 31st more than 20 world leaders will join President Xi Jinping in the northern city of Tianjin for a two-day meeting of the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation, a security forum. Among them will be Russia’s Vladimir Putin (a frequent visitor), India’s Narendra Modi (a rare one) and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, who seldom goes abroad. In recent days Donald Trump said he would visit China “probably during this year or shortly thereafter”. It would be the first such trip by an American president since 2017, when Mr Trump was last there. Great-power relations are in flux.

Oddly, however, one of China’s most senior foreign-affairs officials, Liu Jianchao, is nowhere to be seen. Mr Liu heads the Communist Party’s International Department and, at least until recently, had been widely tipped as the next foreign minister. The department’s website still names Mr Liu as the organisation’s chief. But it does not list any of his activities since July 30th, when he visited a senior politician in Algiers (the department’s job is to build ties with foreign political parties). That is unusual. He had more than 30 meetings in August 2024, the website shows. For him, it was a typically busy month.

Mr Liu’s disappearance was first reported by the Wall Street Journal on August 10th. The newspaper said he had been detained for questioning. Reuters news agency also said he had been taken away, quoting “five people familiar with the matter”. Both reports stated that the reason was unknown. Reuters later said that one of Mr Liu’s deputies, Sun Haiyan, had also been questioned. Ms Sun reappeared at an event on August 15th and has since had other meetings with foreigners, suggesting her troubles, if any, are not as great as her boss’s.

If Mr Liu fails to re-emerge, it would mark another purge at the top of China’s foreign-policy establishment following the disappearance of China’s then foreign minister, Qin Gang, in June 2023. He was replaced the following month by his predecessor, Wang Yi. Officials have still not explained why, though rumours abound about his private life. Last year Mr Qin was also removed from the party’s Central Committee.

Western officials would not cheer Mr Liu’s downfall. A fluent English-speaker who studied at Oxford University, he avoided the aggressive “wolf-warrior” style of diplomacy once voguish among Chinese diplomats (it has receded in the past couple of years). “It is unimaginable that China and the United States would engage in armed conflict,” he said, days before he disappeared. An ability to charm foreigners, however, will not impress the party’s investigators. ■

United States | Lexington

New York is turning 400 and no one cares

But it’s an important moment to celebrate what made the city great

Illustration: David Simonds

Aug 28th 2025|5 min read

It is a little sad, yet also somewhat inspiring, and in any event altogether fitting, that New York City is marking its 400th birthday this year and almost no one gives a damn. Last New Year’s Eve the mayor, Eric Adams, promised a year-long celebration, but denizens would be forgiven for not having detected many events so far. “They’re not doing squat,” says Kenneth Jackson, an emeritus professor of history at Columbia University and the editor-in-chief of “The Encyclopedia of New York City”.

Though disappointed, Mr Jackson is not surprised. “New York has never cared,” he says. As with other historians of New York, the only thing that seems to make him wistful about Boston (a younger city, he notes) is its fascination with its past. Russell Shorto, another historian, says New York “just keeps paving over things”.

It probably does not help that New Yorkers tend to be fractious, and even the history of commemorating the history of New York is ripe for disputation. Just 61 years ago the World’s Fair in Queens celebrated the city’s 300th birthday. Back then the city recognised as its foundational year 1664, when the British seized New Amsterdam from the Dutch and renamed it after the Duke of York. But in 1974 Paul O’Dwyer, the president of the city council, moved to backdate the year displayed on the municipal flag from 1664 to 1625. O’Dwyer, who spoke with the lilt of his native Ireland, insisted he was just out to respect history. The mayor at the time, Abraham Beame, went along with the idea, though one city hall aide dismissed it as “Paul O’Dwyer’s attempt to make us a Dutch city instead of an English one”.

Other possible dates might have included 1609, when Henry Hudson, an English captain exploring under a Dutch flag, sailed up the river that now bears his name; or 1624, when the Dutch West India Company landed settlers—eight of them—on what is now called Governors Island, in New York’s harbour; or 1626, when the settlers notoriously “bought” Manhattan for what was later judged to be a few dollars’ worth of stuff. The year 1625, Mr Shorto says, was “when they sent over shipments of farm animals”.

New York’s historians care less about the date than that New Yorkers should pause to consider how their city vaulted to global pre-eminence from that tiny toehold in the harbour. “What’s important is not whether it started in 1625,” Mr Jackson says impatiently. “It’s just that something happened here, and then became the headquarters of finance and culture and arts and media and just about everything else you can think of.”

O’Dwyer was ahead of his time. Just as he moved to backdate the founding, a new wave of scholarship was starting to reckon with the profound imprint of the Dutch on New York, and on America. Until then New York’s story was seen through an Anglocentric lens, in part because English-speakers told the story and the settlement’s early documents were written in 17th-century Dutch, which few alive could understand. As historians set to work translating documents from New York’s first decades, a picture came into focus of how radically different the Dutch town was from other settlements in the New World. While the theocrats in Boston were hanging Quakers to create a Puritan monoculture apart from the world, the Dutch were haphazardly fostering a polyglot society united largely by a shared interest in being left alone to make money.

The amphibious Dutch immediately saw the potential in New York’s intricate tracery of waterways: the deep harbour, the protected passage eastward through Long Island Sound, and, most of all, the Hudson’s reach to the north, where a valley opened westward to the continent’s vast interior (and where the Erie canal would eventually join New York by water to Detroit and Milwaukee). In 1640, after the Dutch company gave up its monopoly and declared the port a free-trade zone, New Amsterdam became a hub for Atlantic trade. By 1645 a visiting Jesuit reported hearing 18 languages among the few hundred residents (and he probably did not count African and native languages). “Everyone here is a trader,” a resident observed in 1650.

That trade was partly in human beings, a satanic legacy of Dutch commerce. Yet the society in those first years also included free black property owners and women who ran trading companies as well as Portuguese, Bohemians, Arabs, Poles and Mohawks. Even Jews were tolerated, if reluctantly.

Going Dutch

The English saw what was happening and coveted not just the port but its culture. This is the subject of “Taking Manhattan”, Mr Shorto’s latest, fascinating history based partly on the continuing work on Dutch documents. The Stuart monarchy had just returned to the throne, overcoming a Puritan Commonwealth, and the king wanted to bring the righteous Puritan colonies to heel. But when an overwhelming English naval force menaced New Amsterdam in 1664, the commander, Richard Nicholls, negotiated an agreement that, in Mr Shorto’s telling, was less like a surrender than a merger or bill of rights. It guaranteed the residents their rights to property and to keep trading and worshipping freely. It even let them retain an unusual freedom they had won under the Dutch, to choose their own municipal leaders.

“That sets up this dynamic of two ideological power bases in colonial America with very different ways of seeing the world,” Mr Shorto says. “And you can look at a lot of American history as this, you know, back-and-forth between these two, the one based in New York, remaining outward-looking and business-minded and globally oriented.” The other, originally based in Boston, “is puritanical and Christian and America-first. And that’s part of the DNA of the country.” Not just New York, but America, should be celebrating, and pondering, this particular birthday. ■

The Americas | Porcine of the times

Peru’s cartoonish presidential front-runner

In Rafael López Aliaga, or “Porky”, many voters see a man of action

Rooting for troublesPhotograph: Reuters

Aug 28th 2025|LIMA|3 min read

Not many politicians would think it good for their brand to be compared to Porky Pig. But Rafael López Aliaga, the pugnacious conservative mayor of Lima, Peru’s capital, is not like many politicians. He plays up the resemblance, having deployed people in pig costumes to events and adopted a pet pig as his personal mascot. Peruvians simply call him Porky.

In the most recent survey conducted by Ipsos, a pollster, Mr López Aliaga for the first time topped the voting-intention list for a general election scheduled for April 2026. That put him just ahead of Keiko Fujimori, a fellow conservative who narrowly lost the last three presidential run-offs.

The mayor is a wealthy business tycoon and a former city councilman. Like many typical Peruvian politicians, he portrays himself as a champion of the working poor. He has a knack for hogging the spotlight. Sometimes that requires bizarre policy proposals (self-exploding drones to stop criminals) or outlandish promises (his mayoral-campaign pitch was to make Lima a world power).

The cartoon-character capers distract attention from Mr López Aliaga’s darker impulses. He has called for the death of two political opponents (he later said he meant their “political death”), and has suggested that an advocate for assisted dying who was suffering from a terminal illness should take her own life in a warm bath.

Mr López Aliaga, then, does not mind a fight. Since becoming mayor in January 2023, he has waged one bitter battle after another. His attempt to annul an unpopular toll contract ended with Lima on the hook for more than $196m in damages—and perhaps $2.7bn more in a current arbitration suit. His plan to acquire 40-year-old diesel locomotives and carriages from California for use on a proposed rail line has been dogged by criticism. After an acrimonious spat with the transport ministry, it remains unclear when, or even if, they will be put to use. Such antics are costly. Lima’s debt has more than tripled under his leadership, and in June Moody’s, a rating agency, knocked its credit rating down a notch, to below investment-grade.

Blame is reserved for foes real and imagined. Mr López Aliaga often invokes a nebulous “mafia”, most recently for leading the transport ministry to threaten huge fines on a major road-expansion project for which he had not secured an environmental permit. Left-leaning “parasites” infest the bureaucracy, imposing their “terrorist logic” to spread suffering. His go-to culprits—journalists, technocrats and progressives—make for easy punching bags. Peruvians are sick of bureaucratic red tape, and scandals have tarnished leftist politicians. Voters are fed up.

They have a right to be. The election was called in March by President Dina Boluarte to put an end to the lawlessness that has descended on Peru. That includes street-gang shakedowns, contract killings, illegal mining and corrupt cops being protected by their lawmaker pals.

In Mr López Aliaga, many voters see a force for order, or at least change. So-called “Porkylovers” say his pushy ways get things done, his business acumen would help un-gum the machinery of government and his wealth would make him less likely to pinch from the public purse. And socially conservative Peruvians like his strident views against abortion and gay marriage.

If, as expected, Mr López Aliaga throws his hat in the presidential ring for a second time, his pugilist-populist ways give him a decent shot. Yet although he topped the August poll, he just squeaked into double-digit support. That is a sign of Peru’s extreme electoral fragmentation, and a reminder that anything can happen. A record-high 43 parties registered for April’s election. No candidate is likely to gather a simple majority, so a second-round vote in June is all but guaranteed.

What might a Porky presidency look like? More capers and more controversy, to be sure. Mr López Aliaga has said that most government ministries should be eliminated, that dangerous prisoners should be sent to El Salvador and that more troops should be put on Peru’s borders. And that’s not all, folks.■

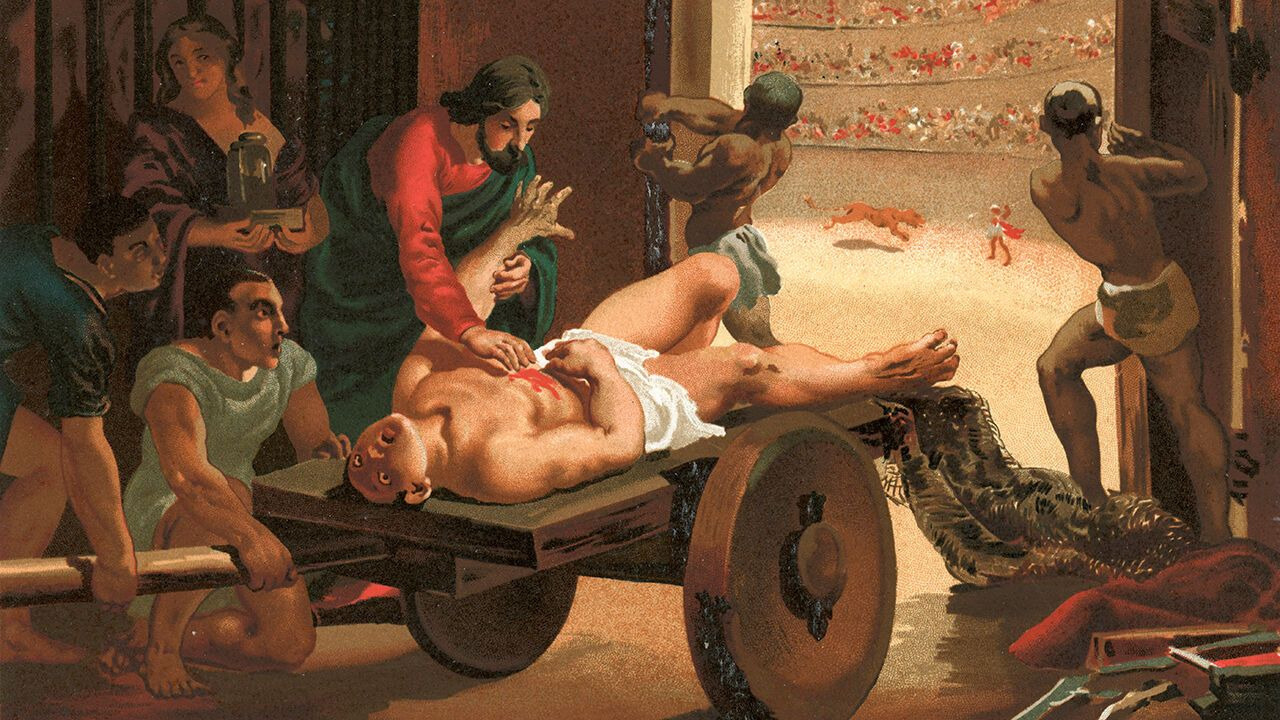

Middle East & Africa | Bibi’s deadly vacillation

Israel’s prevaricator-in-chief

Netanyahu is concerned with both his immediate and long-term political survival

Zamir guns for his bossesPhotograph: Shutterstock

Aug 28th 2025|JERUSALEM|4 min read

On august 24th, six months after being selected as the new chief of staff of the Israel Defence Forces (idf), Lieutenant General Eyal Zamir broke publicly with his government’s policy. On a visit to a naval base, he said the idf had, in its previous operations in Gaza, “created the conditions for the release of the hostages”.

His use of the past tense was a pointed message to Binyamin Netanyahu, the prime minister. Israel’s most senior general opposes new orders he has been given to occupy Gaza city. He will obey, but he would rather see a ceasefire.

Read all our coverage of the war in the Middle East

The absence of any clear strategy from Israel’s government has led to tensions between the idf and Mr Netanyahu’s government throughout the Gaza war. In recent weeks the prime minister has taken his strategic prevarication to new levels. That is lethal for Gazans and dangerous for the hostages. But Mr Netanyahu is driven, as ever, by fears for his own political survival. Increasingly, he is looking further ahead, to elections due by October next year.

Ending the war would prompt his allies to abandon him. But the idf’s opposition makes it hard for him to expand it as much and as quickly as the far right would like. In early July he told the idf to start preparing a “humanitarian city”, a tiny corner of southern Gaza where the entire population of 2.1m would be concentrated while Israel’s troops destroyed Hamas in the rest of the territory. The idf pushed back, calling the plan unfeasible and illegal.

Mr Netanyahu changed course, opting for a smaller-scale plan focused on Gaza city, now home to nearly half the population. General Zamir objected once again, but was overruled. The idf has launched Operation Gideon’s Chariots B but so far only manoeuvred on the outskirts of Gaza city. Mr Netanyahu alternates between urging haste and tolerating delay.

His vacillation is killing Gazans. For over two months his government blocked all aid from entering the strip. Then it promoted aid hubs run by the shadowy Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, aimed at circumventing international aid organisations which Israel claims are captured by Hamas. Hundreds of hungry Gazans were killed trying to get to the hubs. There is famine in wide areas of the strip.

Israel has since allowed international aid groups, private companies and criminal gangs to bring in very limited quantities of food. On August 22nd the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, which monitors food shortages around the world, reported that parts of Gaza have reached famine levels of “starvation, destitution and death” (Israel has denied this, disputing the report’s methodology).

The government’s diplomacy has been similarly muddled. For months Israel has been engaged in indirect talks with Hamas aimed at securing a temporary ceasefire in Gaza in return for the release of half the hostages. This would have provided Gazans with some respite from Israel’s attacks, which have by now killed at least 60,000 people there, mostly civilians. The negotiations broke down and Mr Netanyahu, who had originally insisted on a brief ceasefire, now says he will only agree to one that brings all the hostages home and ends the war on Israel’s terms. A new temporary deal, brokered by Egypt and Qatar, to which Hamas has agreed, has received short shrift from his government.

Mr Netanyahu’s focus is again not on peace, but on his own political survival, both immediate and longer term. His strategy is based on two things: keeping his far-right coalition together; and hoping that eventually “victory” in Gaza will revive public trust in his leadership.

So far he has succeeded at the first bit. He has clung to office by continuing the war and dangling before the ultranationalist parties the prospect of realising their dream of annexing Gaza and the West Bank. They grumble that he is not decisive or far-reaching enough, but realise that under any other prime minister Israel would have stopped fighting in Gaza long ago.

On the second, though, he is failing. The Israeli public seems to have turned irrevocably against its longest-serving prime minister. Mr Netanyahu was convinced last year’s devastating campaign against Hizbullah, the heavily armed Shia militia in Lebanon, and the 12-day war with Iran in June, would show Israelis he was indispensable. But if anything those short, decisive wars highlighted the contrast with Gaza, where his government has dragged Israel into a bloody and unending morass against Hamas, a much weaker enemy. Three-quarters of Israelis support a deal to save the hostages and end the war. Hundreds of thousands have taken to the streets in recent days to demand one.

Decision time

Mr Netanyahu has paid them little heed. But by October 2026 at the latest, he will have to fight an election. The polls currently say he will lose. Rather than adjust course, he is doubling down on his hardline alliance, in the hope that, even if he fails to win a majority, a fragmented opposition will fail to form a coalition to oust him. That tactic has worked for him in the past but it is risky. It is reprehensible that political gamesmanship is Mr Netanyahu’s main focus, while Israeli hostages remain in captivity, and Gazans starve and die. ■

Europe | Charlemagne

Ten years later, “Wir schaffen das” has proved a pyrrhic victory

The providential folly of Angela Merkel’s migration policy

Illustration: Peter Schrank

Aug 28th 2025|5 min read

It was the worst of policies, it was the best of policies; it may not even have been intended as a policy at all. In late summer 2015 as a tide of Syrians, Afghans and others marched towards Europe in search of refuge, Angela Merkel announced that Germany would, in effect, take them all in. The move startled the chancellor’s critics and allies alike. By upending migration policy, had the methodical-to-the-point-of-obstructive leader revealed a rash streak on perhaps the most fraught topic in European politics? Mrs Merkel’s answer to both fans and naysayers came in the form of a phrase that came to mark her 16 years as chancellor: Wir schaffen das, We can handle this. Over 1m migrants soon made Germany their home. A decade later Mrs Merkel has been proved right, but in a pyrrhic sort of way. Germany did manage, and better than anyone might have expected. But the costs of doing so have mightily strengthened her political opponents.

The run-up to the anniversary of Mrs Merkel’s proclamation on August 31st was marked by a civic jolt. The Alternative for Germany (AfD), a party marked by such deep-seated xenophobia that the country’s security services have designated it as “extremist”, topped some national polls. (In 2015 it had been a marginal political force too small to get into parliament.) To critics of Wir schaffen das that is the upshot of what they see as Mrs Merkel’s naive kindness to outsiders. Yes, of course Germany could muddle through, as could any rich country of over 80m people taking in a large wave of migrants. But many of the Germans made to do the muddling were not the well-off liberal types on hand to welcome Syrians at train stations with teddy bears and flowers. Rather, the costs fell on those living far from the fashionable bits of Berlin and Munich, whose kids’ classmates now spoke no German. They had expected the state to look out for them, but instead felt patronised by their own chancellor. Today seven in ten Germans feel the state is overwhelmed. The visceral feeling that the authorities were losing control—the stuff of populist politicians’ rhetoric, as Britons well know—took root in 2015.

Those who cheered Mrs Merkel’s approach at the time can feel some vindication too. For them the Willkommenskultur of that summer was an act of national redemption, a moral feather in the German cap. Forget grubby politicking, this had been a case of a leader following her compass, and taking the country along with her. The costs were high—all things worth doing have a cost—but not unmanageable, just as she had said. Doomsday predictions of migrants being on benefits for decades, hobbling the welfare state at the expense of the native-born, proved wide of the mark. Recent data show that around two-thirds of the migrant intake of 2015 now work, not far from the employment rates of native-born Germans (although migrant women have not fared as well). Though costly in terms of benefits, newcomers helped alleviate firms’ concerns of a labour shortage in the German economy.

It wasn’t just Germans, old and new, whom Mrs Merkel had swept up in her bid to welcome the world’s downtrodden. Europe had helped Germany recover from the moral abyss of the second world war, then permitted its unification in 1991. Whether or not she intended it that way, Mrs Merkel was seen as repaying the favour. For the throwing open of borders was a boon not just to migrants, but to Germany’s neighbours, who had no appetite for dealing with the incoming huddled masses. Now they could send them to Germany instead; Hungary’s Viktor Orban helpfully put on buses to help ferry the migrants northward.

Here, Mrs Merkel miscalculated. She had described dealing with migrants as “the next great European project”, the kind of language used for the creation of the euro or the Schengen passport-free travel zone. But demands from Germany that other European Union countries help out by taking their “fair share” of migrants fell on deaf ears. The upshot was that Germany partly reinstated the very border controls that Schengen had abolished. Others followed in time; these days passport checks are rife within the zone. And there was a grubby underside to Mrs Merkel’s principled stand, when she concluded that Germany could not take in thousands of refugees a day indefinitely. The only way to stem the flow of migrants was, in effect, to bribe Europe’s neighbours, notably Turkey, to keep Syrians and others on their territory rather than let them wander to the EU. That has resulted in the bloc toadying to strongmen such as Recep Tayyip Erdogan, when their authoritarian ways should have been called out.

Was it worth it?

Given the shrill tone around migration, it can be hard to draw a nuanced conclusion. It is all too easy to draw wrong ones, however. Pinning the rise of the AfD purely on the events of 2015 is one such case. Even Mrs Merkel has admitted that her “polarising” stand a decade ago had helped the party’s rise. But it was not the only factor. The party’s ideological allies are leading in polls across Europe, including in France and Italy. Germany has a unique history, but it was never likely to be entirely spared the wave of hard-right populism that has enveloped much of the continent.

However one feels about Wir schaffen das, it has aged rather better than Mrs Merkel’s policies that allowed the German economy to become dependent on gas from Russia and exports to China, not to mention her rash shutting-down of its nuclear power plants. Yet a decade on, not much remains of her can-do spirit of 2015. Mrs Merkel’s own party, back in power, has disowned her approach and tightened Germany’s asylum rules. Europe is implementing a “migration pact” that treats asylum-seekers far less kindly. It now looks as though Mrs Merkel spent her political capital on a gamble whose payout turned out to be fleeting. Does that make it a blunder? Perhaps; but a generous and humane one. ■

International | The Telegram

The wrong way to end a war

Dark lessons from history that explain Vladimir Putin’s “peacemaking”

Illustration: Chloe Cushman

Aug 26th 2025|5 min read

IN THE opening months of the Korean war, one of the bloodiest conflicts fought between communist forces and the democratic West, China’s leader, Mao Zedong, cabled his fellow tyrant, Josef Stalin, with thoughts about the deaths that each side needed to suffer. My “overall strategy”, Mao wrote in March 1951, involves “consuming several hundred thousand American lives” in a war lasting years. Only then would the imperialists realise that, in the newly founded People’s Republic of China, they had met their match. Mao had already sent armies of “volunteers” to the Korean peninsula, where combat had raged since the previous summer, after a Soviet-sponsored regime in northern Korea invaded South Korea, ruled by an American ally. Coolly, Mao told Stalin that China expected to lose 300,000 more men to death or maiming.

Mao’s disregard for casualties was no rhetorical flourish. By July 1953, when an armistice brought 37 months of war to an end, internal Chinese estimates put his country’s death toll at 400,000 (today, official propaganda admits to 150,000). Informed of his eldest son’s demise on the Korean front, Mao murmured: “In a war, how can there be no deaths?” Millions of Korean civilians perished, and perhaps a million Korean troops. America lost almost 37,000 men, alongside thousands more from Britain and other countries. Korea’s cities were smouldering ruins.

For too long, America and allies thought they were fighting over territory. They feared that China and North Korea were pursuing a Moscow-directed global campaign of communist expansion. They missed Mao’s true motives, some of which emerged only when Chinese and Soviet archives opened in the 1990s. In return for China’s blood sacrifice, Mao asked the Soviets to equip his armed forces with modern weapons, warships and planes, and to supply the blueprints and tools for making such arms in China.

Control of the peninsula swung between communist and Western armies several times, before settling into a stalemate around the 38th parallel, a line cutting Korea in two. Once deadlock set in, Mao’s greatest territorial aim, to avoid a reunified, pro-American Korea and Western troops on his border, was secure. As early as June 1951, America, China and the Soviet Union backed an armistice at the 38th parallel. Still, the war ground on for another two years. Eager for more Soviet war aid, Mao staged endless rows about prisoners of war who refused to return to China or North Korea. Fully 45% of American casualties occurred after talks began. Veterans recalled deadly night-time skirmishes on hills overlooking the floodlit negotiation compound. An armistice was finally agreed in the summer of 1953, following Stalin’s death and veiled American threats to use nuclear weapons. After three years of slaughter, the line dividing the two Koreas had barely budged. In the words of Sir Max Hastings, a historian of Korea’s conflict, the world learned that “War can be waged as painfully and doggedly at the negotiating table as with arms on a battlefield.”

Now Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, is stalling his American counterpart, Donald Trump. Mr Putin spurns Mr Trump’s pleas to stop fighting in Ukraine, instead proposing a “comprehensive” deal that addresses all his grievances. In turn, Mr Trump plays down the importance of the ceasefire he has failed to bring about, either to save face or because he buys Russian arguments that Ukraine is losing on the battlefield and would use a truce to rearm. Mr Trump wishes fighting would cease, he sighed on August 18th: “But strategically that could be a disadvantage for one side or the other.” Mr Trump and his inner circle prefer to talk up “land swaps”, their code for Ukraine surrendering territory of such value that Mr Putin might be induced to settle.

To hear Mr Trump tell it, pushing belligerents to cut deals is an intrinsically worthy pursuit because it is the opposite of war, which is senseless and wasteful. Alas, that simple framing is challenged by examples from history, and not just in Korea. Ceasefires do not matter only because they pause the killing. They can also signal acceptance that a war will not have a military resolution.

Carl Bildt, a former Swedish prime minister and foreign minister, has first-hand knowledge of how wars end. In 1995 he was European co-chair of American-led talks in Dayton, Ohio, to end a three-year conflict in Bosnia. America’s and Europe’s goal at Dayton was peace. Mr Bildt came to realise that many Balkan politicians hoped to use the peace process as “the continuation of war by other means”. Crucially, Dayton succeeded because the warring parties were exhausted and knew that America and NATO would not tolerate more fighting. That left only a political solution. “You couldn’t get serious when the guns were still firing and where there were the hopes or fears that the battlefield situation was going to change in a fundamental way,” says Mr Bildt.

Not everything is a real-estate deal

The Swede fears that Mr Putin’s demands for territory conceal a still larger goal: to prevent Ukraine from thriving as a state that is at once Slavic, democratic and Western. He also distrusts Mr Putin’s call to tackle all disputes at once. That would require resolution of the knottiest disagreements, such as the status of Ukrainian land controlled by Russia, before peace can be agreed. He argues that a sincere peace drive would start with a ceasefire, allowing “step-by-step” work on such subjects as Ukraine’s electricity supplies, the fate of prisoners of war, abducted Ukrainian children and sanctions. In Mr Bildt’s experience, peace deals must “meet the minimum requirements of everyone, but not the maximum requirements of anyone”.

Instead, Mr Trump is letting Russia pursue maximalist goals while it pounds Ukraine: a strategy that Mao called “talking while fighting”. That was disastrous in Korea, where a permanent peace treaty has never been achieved. Why would it be different now? ■

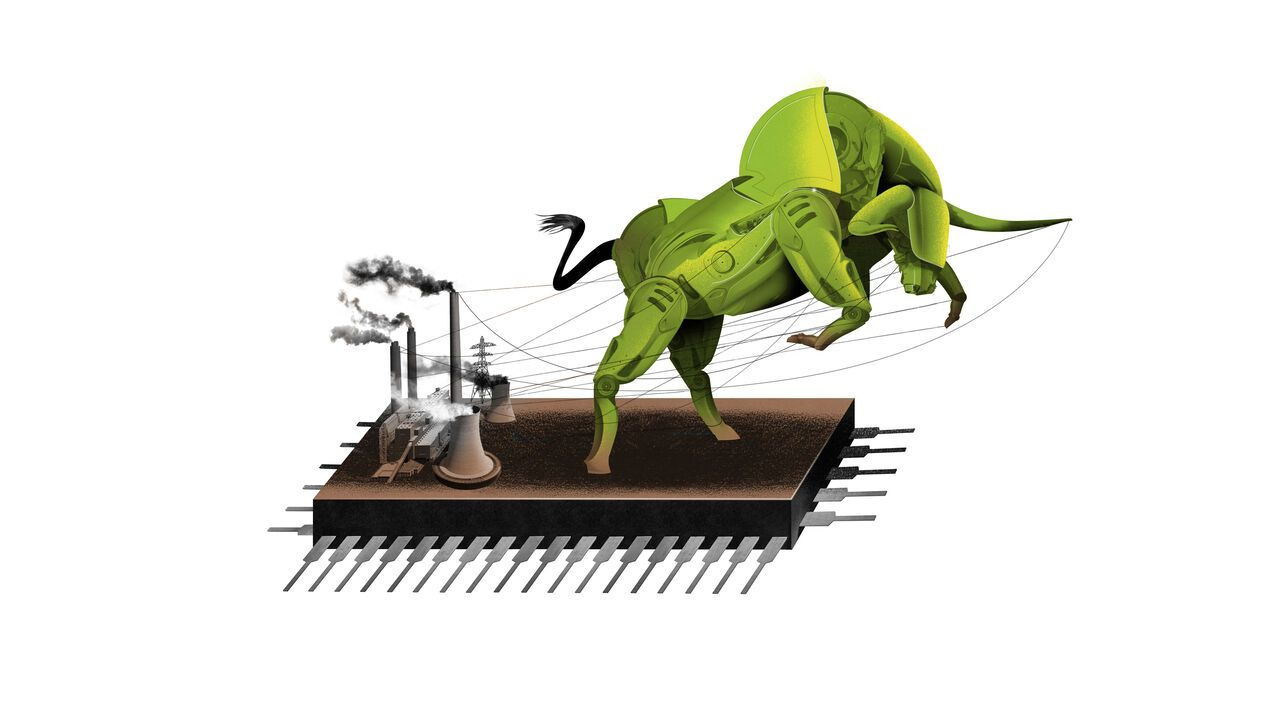

Business | Schumpeter

How a power shortage could short-circuit Nvidia’s rise

Too many chips, too little juice

Illustration: Brett Ryder

Aug 28th 2025|5 min read

ON AUGUST 27TH Nvidia performed what has become a quarterly ritual beating of expectations. Analysts forecast that the chipmaker would sell $46bn-worth of semiconductors in the three months to July. It made closer to $47bn. Its latest Blackwell graphics-processing units (GPUs), whose unrivalled number-crunching prowess has won over artificial-intelligence modellers, are flying off the shelves. So are its GB-series AI superchips, which combine two Blackwells with a general-purpose processor. Nvidia probably sold over 600,000 Blackwells and nearly as many GBs, nearly 20% more than last quarter, accounting for almost 60% of total revenue. It is on track to sell 2.7m and 2.4m, respectively, this year.

Nvidia bulls on Wall Street now reckon that America’s chip champion could be worth $5trn before long, having become the world’s first $4trn company only in July. It looks, in the words of many a breathless commentator, unstoppable. And yet fittingly for an unstoppable force, Nvidia is about to come up against an immovable object. Or at least an object that has not moved much in decades—America’s power grid.

Energy has not historically been a constraint on computing. Even as rocketing internet traffic increased the workloads of the world’s data centres nine-fold between 2010 and 2020, their overall power use stayed completely flat. Every generation of chips was more efficient than the last. AI has turned this trend on its head. A non-AI data-centre computing unit, or rack, needs around 12 kilo-watts (kW) of power to run. An equivalent AI module requires 80kW when training large language models like the one behind ChatGPT, then 40kW when responding to users’ prompts. Zippier semiconductors can consume a good deal more than that.

Nvidia’s are, naturally, the zippiest of all. A single Blackwell chip needs 1kW, three times more than its Hopper predecessor. Racks contain dozens of them. Nvidia sells modules packed with 36 GB superchips, which is to say 72 Blackwells and three dozen general-purpose chips, designed to operate at 132kW. A secondary cooling system to stop the semiconductors overheating from all that thinking can add 160kW per rack.

Tot it all up and the extra power requirements are staggering. Analysts predict that between February 2024 and February 2026 Nvidia will have sold some 6m Blackwells and 5.5m GBs. Assume that half of these end up in America, in line with its home market’s historical revenue share. If installed and operated at capacity, those chips would raise American power demand by 25 gigawatts (GW). That is almost twice as much as all of America’s utility-scale producers added in 2022 and not far off the 27GW they managed in 2023. And that is not counting next-generation Rubin chips Nvidia plans to launch next year, or AI racks sold by rivals such as AMD, not to mention other power sinks such as electric cars.

A recent global survey of data-centre managers by Schneider Electric, a French maker of energy-management kit, found that available power and transmission capacity was a near-universal concern. It occupied the minds of executives more than anything else, including access to those hot-ticket GPUs. Bernstein, a broker, estimates a potential power shortfall in America of 17GW by 2030 if the chips get more energy efficient, and 62GW if they don’t. Morgan Stanley, a bank, puts the gap at 45GW by 2028.

If American power companies do not pick up the pace, in other words, chip sales could stall or sold chips could lie idle. The latter would weigh on the profits of AI powerhouses such as Alphabet and Microsoft that are splurging billions on GPUs. The former would drag down Nvidia. Neither eventuality appears to be factored into the tech giants’ lofty valuations. The implicit assumption seems to be that American electricity providers will step up.

The power sector is starting to stir from a prolonged motionlessness in which capacity edged up by low single digits annually. Between 2022, when ChatGPT ignited the AI boom, and the 12 months to June this year, the combined capital spending of America’s 50 biggest listed electricity providers rose by 30%, to $188bn—a compound annual increase of 7%, adjusting for inflation. According to S&P Global, a data provider, they are planning to add new plants with a collective capacity of 123GW, on top of the 565GW currently in operation. Suppliers of power equipment such as Schneider Electric are seeing American sales accelerate.

Current concerns

Yet reasons for caution abound. Industry bosses are unaccustomed to running a growth business and could stumble. Ambitious plans aside, their firms’ new capacity actually under construction amounts to just 21GW between them. Even if they do try to build more plants, they may struggle to fit them out. Manufacturers are in no rush to expand production. The world’s 100 biggest makers of electrical equipment have cut their capital spending by 3% a year since 2022 in inflation-adjusted terms. That could spell pricier equipment, made dearer still by tariffs.

Analysts expect listed power companies’ sales to grow at an annual rate of 6% between 2025 and 2028 in nominal terms, up from 4% nominal growth since 2022 but no bonanza. As the canonical dividend stocks, they have paid $87bn to shareholders since the start of 2023, leaving less cash for investments. Many are regulated monopolies, and legally obliged to reflect more capital spending in higher bills. This would irk inflation-wary Americans and, worse, the business-browbeater-in-chief in the White House.

Some data-centre operators are taking things into their own hands. Alphabet is putting solar panels and battery storage in some data centres. Meta’s project in Louisiana will run in part on natural gas tapped on site. Still, it is power companies that generate virtually all American electricity. Without their help, Nvidia’s epic surge will sooner or later power down. ■

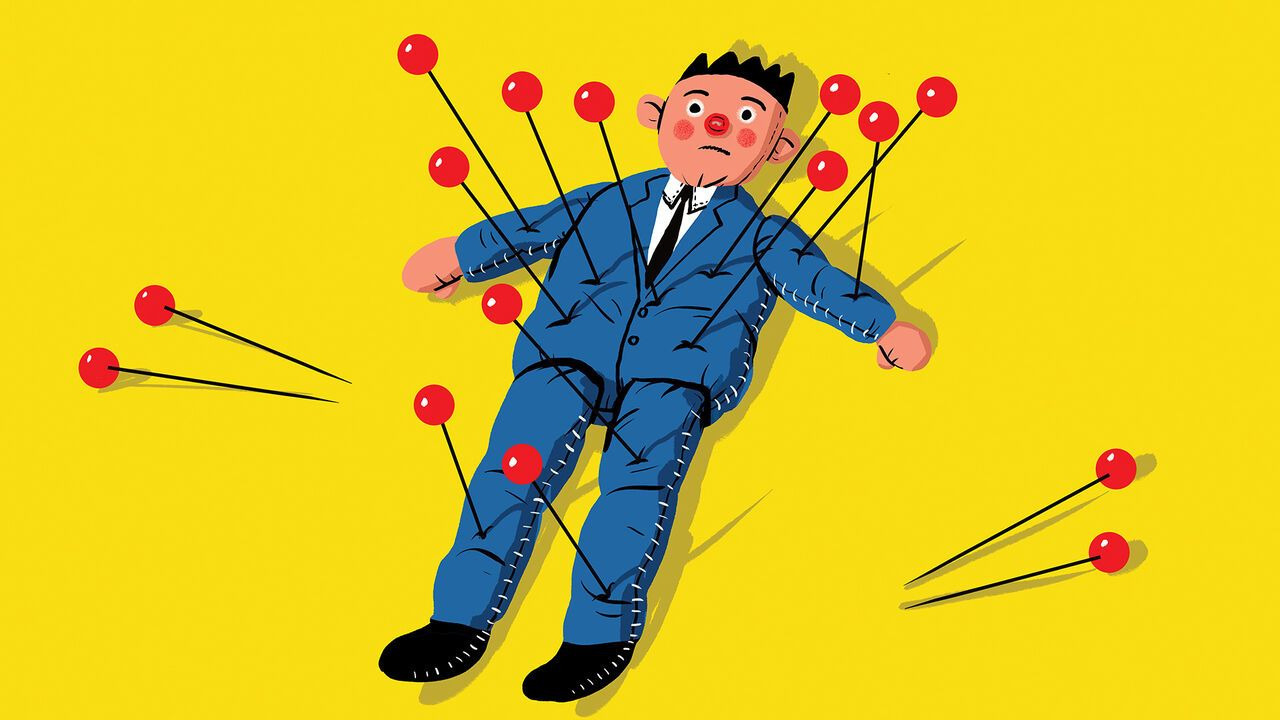

Business | Bartleby

Feuds, grudges and revenge

Welcome to the dark side of the workplace

Illustration: Paul Blow

Aug 28th 2025|3 min read

One of the more touching on-screen relationships is that between C-3PO and R2-D2, two robots who appear in the “Star Wars” films. The actors behind the droids got on less well. “He was in a box he couldn’t do anything with,” Anthony Daniels dismissively said of Kenny Baker, the man who played the part of R2-D2. “Rude to everyone”, was Baker’s verdict on his fellow actor.

Antipathy need not prevent good work. Messrs Baker and Daniels managed to put aside their differences on set (it must help to be able to roll your eyes without being seen). And friction can be good for organisations: a contest of ideas about how to get something done ought to yield better outcomes. But such “task-related” disagreements can easily curdle into something more personal and destructive.

Every workplace has a simmering feud or long-run grudge. These fractured relationships can exact a heavy price. Research published for Acas, a mediation service, in 2021 put the annual cost to British organisations of resolving work conflicts at £28.5bn ($39bn), factoring in resignations, sick leave, dispute resolution and the like. And that’s before you take into account the hidden costs of withheld co-operation and time lost on Gothic revenge fantasies.

Humans are hard-wired for disagreements to escalate. One of Lindy Greer’s favourite classroom exercises at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business is to have students at different tables learn slightly different rules for the same game (aces high in some cases, aces low in others, for example). When people move tables and start to unexpectedly claim victory, other players are far quicker to assume they are stupid or cheats than to question whether they have a different understanding of the game. This is a good demonstration of the “fundamental attribution error”—the tendency for people to assume that the actions of others are determined by their personalities, not by external factors.

Once someone feels they have been intentionally wronged, their instinct is to get even. “The Science of Revenge”, a recently published book by James Kimmel, argues that a desire for vengeance activates the same brain circuitry as a drug addict thinking about their next hit.

In a study conducted by David Chester of Virginia Commonwealth University and C. Nathan DeWall of the University of Kentucky, participants played a computer game in which a virtual ball is tossed between three players; in some iterations of the game, the ball is passed back and forth between two of them, conspicuously ignoring the third player. Rejected players are shown a visualisation of a voodoo doll representing their partners, and asked to choose how many pins they would like to stab it with. The moral of the story: pass the ball to everyone.

Organisations have features that are particularly liable to stir up bad blood. Power struggles pervade firms: Ms Greer’s research suggests that people on senior leadership teams can be particularly sensitive about protecting their turf. Organisations can also make forgiveness harder, says Thomas Tripp of Washington State University. Dispute-resolution processes are definitely better than people seeking to exact their own revenge (“a very sloppy form of justice”, he says) but overly legalistic approaches can also serve to drag things out.

The solution to all this seething lies partly with managers. Disrespectful corporate cultures are fertile ground for feuds. It’s usually worth bosses trying to sort out ructions informally before getting HR involved. Framing some types of disagreement as being for the good of the firm might stop conflict escalating.

But individuals are best placed to stop things from spiralling out of control. Ms Greer recommends asking follow-up questions whenever you are in a disagreement, so that you understand where someone is coming from rather than assuming the worst of them. And if you ever end up ruminating about an apparent slight, Mr Tripp recommends the adage known as Hanlon’s razor. “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity,” is not the most generous way to interpret the behaviour of colleagues. But it might help subdue your craving for revenge. ■

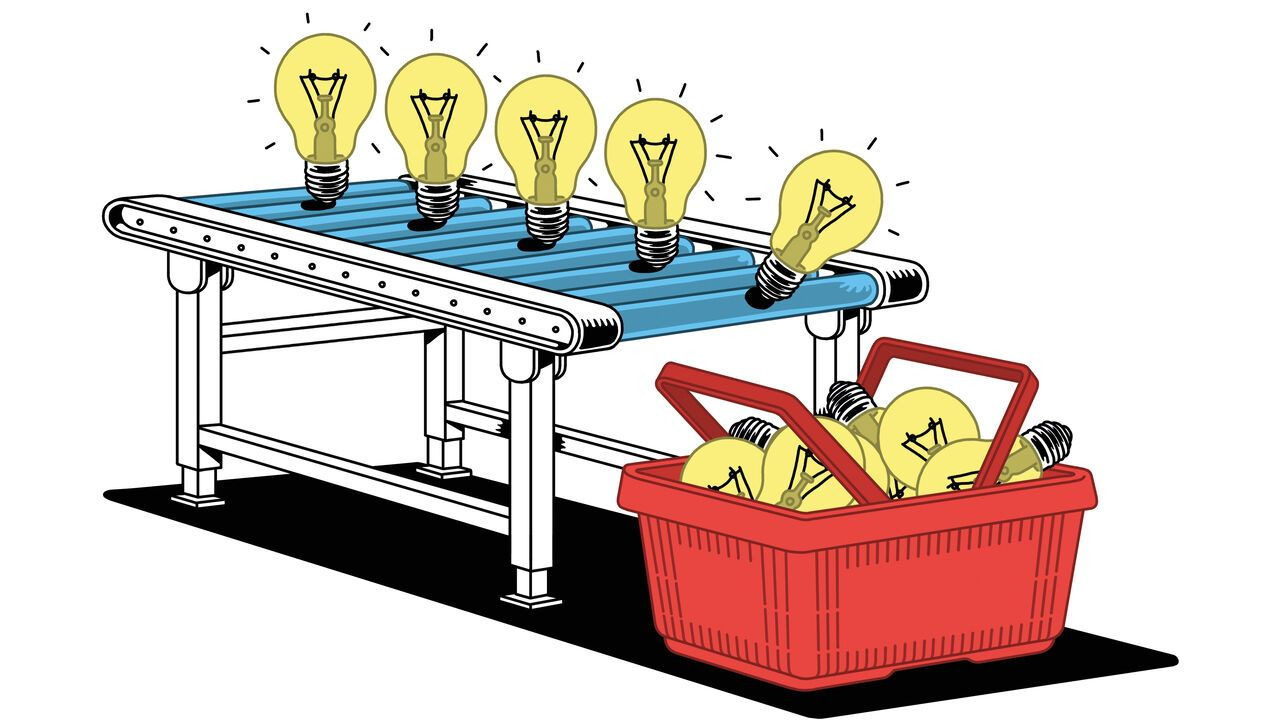

Business | The ideas factory

How China became an innovation powerhouse

Its state-led model has generated impressive results. But the costs are mounting

Illustration: Olivier Heiligers

Aug 25th 2025|CHONGQING, HANGZHOU AND SHANGHAI|6 min read

Most STARTUPS need time to prove that they can be trusted with investors’ money, let alone dangerous technologies. But not Fusion Energy Tech, a Chinese company based in the city of Hefei that was carved out two years ago from a nuclear-research lab. In July it announced that it would be commercialising a plasma technology derived from fusing the nuclei of atoms, which produces a reaction much hotter than the sun. It has already developed a security-screening device using related technology that is popping up in local metro stations. Commuters walk past them every day.

Xi Jinping, China’s supreme leader, is fixated on beating the West in new technologies. Chinese businesses already dominate areas including electric vehicles (EVs) and lithium batteries, and are fast taking the lead in emerging fields such as humanoid robots. The country’s growing technological prowess is thanks in part to the Communist Party’s conveyor belt of innovation, which takes ideas developed in state-run labs and universities and turns them into commercial products. The process, often referred to as an “innovation chain” in policy documents, has led to rapid advances in a number of fields.

Yet the costs of China’s model are steadily mounting. Critics argue that it has wrought a vast misallocation of resources which is dragging down economic growth. Before long, China’s state-led approach to innovation could prove unsustainable.

China’s innovation chains often start with grants for researchers, who find a placement in state-backed labs. These, in turn, are fertile ground for government officials, who identify good ideas and help research teams set up companies, often within local development zones.

A recent beneficiary of that process is Theseus, a company based in Chongqing that makes computer-vision sensors. In 2019 it was little more than a group of scientists from the state-backed Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics in the city of Xi’an, who would meet in a teahouse to discuss commercialising their work. A district government in Chongqing, hoping to develop a supply chain around their technology, provided funding and helped the scientists launch their company in an industrial zone in 2020.

By 2024 Theseus had become a leading player in its field. It has hired nationally renowned scientists, and in May this year announced it had developed a new display screen using AMOLED technology, which provides a sharper picture quality, in partnership with state-owned China Mobile, the country’s largest telecoms firm.

State-backed research institutes, including labs and universities, are increasingly commercialising their innovations in other ways, too. Some have established marketplaces where companies can bid directly on their patents. The Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Harbin, another city, recently auctioned off the patent behind a genetically modified soyabean it had developed. In such cases an institute will often deploy technicians to the company buying the technology to help them make use of it.

One gauge of the strengthening ties between China’s private sector and its research institutes is the revenue the latter collect when they sell their ideas, co-develop technology or provide consulting services. Between 2019 and 2023, the latest year available, that figure nearly doubled, to 205bn yuan ($30bn).

The benefits of collaboration flow in both directions. In biotech, for instance, state researchers have been able to tap into private resources to aid their work, notes Jeroen Groenewegen-Lau of MERICS, a think-tank in Berlin. University researchers are often granted access to industrial fermentation facilities at local companies, which are used to harvest bacteria.

Innovation nation

Hefei offers perhaps the best example of the drawing together of China’s scientific and business communities under state direction. The city’s government invests in private companies, builds supply chains around them and acts as an interface between labs, universities and the private sector. Fusion Energy Tech is but one of its many successes; plasma-fusion cancer treatments developed in the city are now entering trials, and quantum-secure mobile services developed there are already on the market.

Hefei’s government has focused in particular on working through technological bottlenecks that market dynamics alone may have little incentive to resolve. One example is in the quantum industry, where certain low-temperature dilution devices that were available only from a few foreign suppliers are now being built locally, even if some experts remain sceptical of their performance.

China’s central government hopes to take the best such systems of collaboration and replicate them across the country. In March the National Development and Reform Commission was granted control over a 1trn-yuan fund for investing in technology. Since 2023 it has been run by Zheng Shanjie, formerly the highest-ranking party official in Anhui province, where Hefei is located. The Ministry of Industry and Internet Technology (MIIT) has begun overseeing the commercialisation of ideas within industrial zones, notes Hutong Research, a consultancy based in Beijing. In April Li Lecheng, who is credited with transforming two inland cities into hubs for green energy, was appointed the head of MIIT, suggesting that the party hopes to see many more such transitions.

For Chinese companies, the breadth of innovation under way in the country offers significant advantages. For one thing, it makes it easier to break into new industries, notes Kyle Chan, a researcher at Princeton University. One example is Xiaomi, originally a smartphone-maker, which was able to build a successful EV business in China in about three years. The range of innovation has also helped give rise to new industries. China has become a leader in the nascent business of flying taxis in part by drawing on its expertise in both EVs and drones.

No solution to involution

For all these successes, however, China’s innovation model comes with costs—and these are mounting. Perhaps as much as 2% of GDP goes towards subsidising industries in some form or another. As the state has played a greater role in directing innovation, private venture-capital investment has collapsed, falling by 50% year on year in the first half of 2025, according to KPMG, a professional-services firm.

The payoff from the state’s largesse is also becoming increasingly unclear. China’s total factor productivity, which measures how well it makes use of capital and labour, has stalled. Some efforts by local governments to build clusters of expertise have failed, including the city of Nanning’s attempt to develop an EV supply chain.

State subsidies have also led to severe overcapacity in many industries. The vast majority of China’s EV-makers, for example, are not profitable. Too many businesses now fight for the same customers, a state of unbridled competition with few winners often referred to as “involution”. Meanwhile, pursuing customers abroad is becoming more difficult amid resistance from foreign governments. What is more, some technologies are being developed in China without clear evidence of a market for them. People working on humanoid robots complain that there are umpteen companies all producing similar products without much genuine demand.

China’s state-led approach to innovation has helped create many world-class firms, but the return on investment may be too low for it to continue much longer. The debts China has accrued from funding innovation are vast and unsustainable, argues Daniel Rosen of Rhodium Group, a research firm. Last year public debt, including the amount owed by local-government financing vehicles, reached 124% of GDP. Eventually Mr Xi may have little choice but to dial down government support for new technologies. At that point China’s conveyor belt of innovation could grind to a halt. ■

Finance & economics | Buttonwood

Why you should buy your employer’s shares

Even though doing so flies in the face of most financial advice

Illustration: Satoshi Kambayashi

Aug 27th 2025|4 min read

It is not hard to see why Jamie Dimon owns a lot of shares in JPMorgan Chase. He is the bank’s boss and its shareholders want his interests to be aligned with theirs. Paying him mostly in stock, rather than cash, helps ensure that they are. An executive with a significant proportion of savings invested in their firm’s shares has tied their future to the company’s. This discourages them from doing things that might pad their wallets in the short term at the expense of shareholders’ long-term returns, such as expanding the firm unsustainably fast. The incentives are stronger still if—as with Mr Dimon—the boss is promised shares for delivery some time hence, or if any sales prompt newspaper headlines.

It is rather more surprising that many mid-level bankers own a lot of their employers’ stock. Banks probably benefit from awarding them shares: as with bosses, aligning rank-and-filers’ interests with shareholders’ makes sense, especially when relatively junior employees can risk the firm’s funds and reputation. But the bankers themselves might well make their living from preaching the virtues of diversification to clients. This gospel says that tying your savings to your employer’s prospects is unwise, since you already depend on them for your salary. It is particularly risky if you work in an industry famous for culling staff in down years. Such people know better than anyone what to do with a stock award: sell it and use the proceeds to buy investments that spread your risk rather than concentrating it.

At this point your columnist, a mid-level financial journalist who purports also to understand diversification, must confess some sympathy with these bankers. This is because he owns shares in The Economist Group. Worse, he did not even receive them as part of his pay, but actively decided to invest. Here, then, is why you should consider flouting the best financial advice around and buying shares in your employer.

For a start, doing so might come with some psychological upside (provided you are not too troubled by taking unwarranted risks with your savings). Left-wingers often approve of employee ownership because it gives workers a slice of the profits that would otherwise accrue only to avaricious capitalists. Right-wingers like it because it ushers workers into the capitalist tent. Less is said about the quiet feeling that you are on the same side as your employer, rather than having been pitted against them. Worried that you are overworked for your salary, or that too little of your firm’s revenue flows into wages? Any gains are going to shareholders, so it helps to be one of them—even if you own too few shares to benefit much. The hedge might be more emotional than financial, but it is not nothing.

Then there are the more cold-eyed advantages. Suppose you work for a privately owned firm that is about to be taken over by a competitor (which, for the record, The Economist is not). If you have spurned all offers to buy shares, the first you might hear of the takeover is when the rival company’s executives march into your office and start laying people off. If you are a shareholder, though, you might get some warning: no matter how small your holding, you will probably get a vote on the acquisition.

For some, investing in their employer might also be a rare opportunity to gain exposure to a kind of asset that they might otherwise have difficulty acquiring. Anyone can buy shares in JPMorgan, but buying private equity is more difficult for retail savers, even now that some barriers have begun to come down. Access to the high-risk, and potentially high-reward, leveraged buy-outs that powered the growth of private markets in the 2010s is still mostly limited to big, institutional investors.

A frequent exception is the employees of companies being bought out, who can often invest on the same terms as the giants. Their doing so would horrify a diversification purist, adding the extra risk of leverage to the double whammy of betting savings on the firm that pays their salary. Yet such employees are also well placed to judge the wisdom of the buy-out: whether borrowing costs can be met, for instance, or if the growth required to justify the valuation is realistic.

None of this means anyone should invest a big share of savings in their employer unless they are obliged to—especially if they work for a listed firm, with shares that confer fewer advantages. A small stake, though, might be worth defying financial advisers. And for your columnist’s sake, in more ways than one, please keep buying The Economist.■

Finance & economics | Free exchange

Trump’s interest-rate crusade will be self-defeating

New research shows the importance of central-bank credibility

Illustration: Álvaro Bernis

Aug 28th 2025|5 min read

There are two ways, the world’s central bankers learned at this year’s Jackson Hole conference, to tame a horse. You can break the animal with fear, but it will never forget the pain. The kinder way, shown to attendees one evening, is to set consistent boundaries with gentle consequences (noisy clapping). This, says Martins Kazaks of the Bank of Latvia, is like central banking. Although you can raise interest rates to crush inflation, causing a recession, it is better when everyone believes in the inflation target, so nobody raises prices and wages too much in the first place. If the boundaries are credible, the bank can be gentler.

Officially, the theme of this year’s gathering was labour markets. Unofficially, it was the imperilled credibility of the Federal Reserve. On August 25th, after the conference, President Donald Trump said that he was sacking Lisa Cook, one of the Fed’s governors, for alleged improprieties in her mortgage applications. It was an escalation of his campaign to get the Fed to cut interest rates. The irony is that the Fed already appeared to be moving towards rate cuts. Indeed, two research papers presented at the conference supported the case for lower rates, suggesting both that the Fed should “look through” any tariff-driven inflation, and that today’s rates are high enough to be hurting the economy.

How should the Fed react to Mr Trump’s tariffs? The “Taylor principle” requires that it raise interest rates by more than any increase in inflation above the 2% target. Tariffs will have added 0.8 percentage points to core inflation by December, forecasts Goldman Sachs, a bank. Thus a simple version of the principle indicates that rates would need to be more than 0.8 percentage points higher than they would without tariffs. But although the principle is part of a rule that near-perfectly described central banks’ behaviour from 1987 to 1992, at Jackson Hole Emi Nakamura of the University of California, Berkeley showed that over a much longer period the Fed has frequently deviated from it. Central banks often ignore disturbances, trusting inflation will return to target when the shock subsides. The more credible the bank, the better this works: expectations of low inflation can be self-fulfilling.

This kind of thinking got Mr Powell and his colleagues in trouble after the covid-19 pandemic, when they wrongly argued inflation would be transitory. Yet the Fed did eventually slay very high inflation, despite not having tightened monetary policy by as much as the Taylor principle demanded. In contrast, countries where interest rates rose fast and high suffered even worse inflation. The Fed’s credibility seems to have helped, at least.

Ms Nakamura suggested that post-pandemic inflation may already mean the Fed has less credibility than it did. In response, Amir Yaron, governor of the Bank of Israel, mused that inflation’s eventual fall could have reinforced the idea it will always return to target. The bookies’ favourite to replace Mr Powell is Chris Waller, a Fed governor who at the last monetary-policy meeting dissented in favour of a rate cut. Mr Waller points out that long-term inflation expectations appear to remain in check, despite tariffs.

The second leg of the rate-cutting case is that rates at their current level are slowing the labour market, and need to fall to reach a neutral level. One worry with this argument is that America’s net national debt, which is at nearly 100% of GDP and growing, is pushing up the neutral rate over time, by absorbing the economy’s savings. Even accounting for revenue from tariffs, America is likely to run a deficit of 6% of GDP this year. America’s public finances are in a mess in part because of its ageing population. Older folk require vastly more spending on pensions and health care.

However, at Jackson Hole, Ludwig Straub of Harvard University showed that the flipside of such spending is older people’s appetite to amass and maintain wealth, which raises demand for assets including Treasuries. Mr Straub and his co-authors calculate that this could lower the natural rate of interest sufficiently to allow America to run up debts worth 250% of GDP by the end of the century. That would be music to the ears of Mr Trump, and indeed any politician. It would mean lower rates and more money to spend. Although many attendees took issue with the exact number—which, Mr Straub assured them, applied only in 2100, not today—the broader point that asset demand would prove more powerful than asset supply went mostly unchallenged.

The trouble is that Mr Trump, and American politicians more broadly, are throwing away America’s advantages. Attacks on the Fed weaken the central bank’s credibility. And America is borrowing so much that, whatever the fiscal space, politicians will blow through it. “We need a massive fiscal adjustment no matter what,” Mr Straub said. As several attendees noted, the problem with high indebtedness is that it leaves governments in a precarious position where slight changes to interest rates or a recession can cause far-reaching pain. “It is shocks not stocks that cause crises,” warned Deborah Lucas of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Under populist leaders, nasty surprises are more likely.

A low-rate policy that results from political or fiscal pressure rather than technocratic judgment is more likely to be inflationary, since it raises inflation expectations. Markets seem to understand the danger. It is ominous that long-term bond yields have not fallen much since the Fed started cutting last year. Fighting inflation was delegated to central bankers because, like taming horses, it requires patience and discipline. Unfortunately, governments can always reopen the pen, and allow the animal to bolt. ■

Science & technology | Well informed

Are saunas actually good for you?

The evidence for sweating it out is promising but incomplete

Illustration: Fortunate Joaquin

Aug 22nd 2025|3 min read

Finland is the undisputed sauna capital of the world, with approximately one sauna for every 1.6 people. But voluntary sweating is starting to catch on elsewhere: according to the British Sauna Society, a not-for-profit group promoting sauna culture, the number of public saunas in Britain has more than doubled over the past year.