The Economist Articles for Nov. 5th week : Nov. 30th(Interpretation)

작성자Statesman작성시간25.11.21조회수32 목록 댓글 0다음게시판에서 Economist 기사의 사진이 붙여넣기가 되지 않고 있습니다. 그 사유를 확인할 수 가 없습니다.

모든 기사에 사진이 있는 Economist 기사를 보시려면 하기 링크를 클릭하면 네이버카페에서 사진이 있는 Economist 기사를 볼 수 있습니다.

https://cafe.naver.com/econimist/350

The Economist Articles for Nov. 5th week : Nov. 30th(Interpretation)

Economist Reading-Discussion Cafe :

다음카페 : http://cafe.daum.net/econimist

네이버카페 : http://cafe.naver.com/econimist

Leaders | Donald Trump’s presidency

Welcome to Anything Goes America

Where the loosening of rules and tolerance of corruption will lead

Nov 20th 2025|5 min read

Listen to this story

WHEN HARRY TRUMAN left office he had many opportunities to get rich. He turned them down. “I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable, that would commercialise the prestige and dignity of the office of the presidency,” he said. The man who had given the order to drop two atom bombs lived on income from his memoirs and an army pension worth $1,350 a month in today’s money.

What a sucker! Had he been president in the 21st century, Truman could now be flying private to paid speaking engagements, soliciting donations to his foundation from foreign governments and watching his daughter serve on company boards and his former staffers run their own lobbying shops. Presidents reflect the mores of their times. Truman’s instinct to follow self-imposed rules was characteristic of 1950s America. What, then, are America’s rules in 2025, when the president has accepted a Boeing 747 from one country seeking his favour and a $130,000 gold bar from another, and when his family has struck cryptocurrency partnerships with foreign governments?

Read the rest of our cover package

In Washington, everything appears to be for sale

Shut up, or suck up? How CEOs are dealing with Donald Trump

This is the Anything Goes Era in America. It did not start with Donald Trump, but he has upped the tempo and removed constraints that once held others back. Skirting the rules is all right if you have political protection. Wealthy individuals may rest easy knowing that their tax returns will not be audited. The Department of Justice has dropped prosecutions of politicians for corruption. Its public-integrity unit has been gutted; the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a post-Watergate piece of good-government reform, has in effect been shelved. Past presidents have pardoned donors and relatives, but only on the eve of leaving office. Recipients of Mr Trump’s clemency this year include a cryptocurrency mogul jailed for money-laundering and the son of someone who gave his political movement $1m.

The way the president’s family members have enriched themselves in his second term would have astonished Truman, but it is small print in a $30trn economy. That is not true of tariffs, export controls and mergers, where Mr Trump’s power and personality make it almost a fiduciary duty for company bosses to seek his good graces. Donors to the new White House ballroom, where the East Wing once stood, include firms whose main business is government contracting and those seeking regulatory approval for mergers.

Now heaven knows

When there is one decision-maker and he often changes his mind, it is worth spending a lot to win his favour. Washington lobbyists used to focus on Congress. Now many of them ignore lawmakers and instead sell to clients the impression that they can influence the president or his political movement. All this eats away at the rule of law. Did the administration approve a merger, or grant an export licence, because it was in the national interest? Or because the company bought the president’s goodwill? When anything goes, nobody knows.

It is easy for Mr Trump’s opponents to be shocked—shocked!—at the discovery that people love money and power, and that when mixed together they are intoxicating. And his supporters are right that there can be economic benefits when governments refrain from aggressively enforcing some rules. It may make it easier for companies to operate and foreigners to invest, without worrying that an overzealous bureaucrat will nail them for some petty infraction.

Yet this argument can lead somewhere dismal. All advanced economies have strong laws and expectations that they will be applied impartially. There is no example of a big, mature, wealthy democracy smiling on public corruption and treating rules as arbitrary. So although the eventual costs are uncertain, it is plainly harder for an economy to thrive in the long run when the most important question for a boss is: “Do you know the president?”

The best parallels are found in some emerging markets, where big men rule by whim and companies must suck up to succeed. Or in America’s past, before the rules and habits that until recently promoted clean government were set out. But the Anything Goes Era is different from the Gilded Age or the 1920s, both moments when a dash of political corruption went along with technological innovation and economic growth. Then, politicians stole or skimmed money off contracts to buy political support. That is not how it works now. Outright theft from government appears to be rare. The president does not need to buy his party’s loyalty, since the rank and file love him and Republican lawmakers fear him.

There are other differences, too. In the 1920s federal, state and local government spending amounted to just 5% of GDP, compared with 36% now. In the Gilded Age the presidency was even more marginal to the lives of Americans. The republic has had florid political corruption scandals before. What is new is the mix of a bossy, gargantuan state with the perception that it can be bought.

Surprisingly, the president appears to pay a puny political price for his self-dealing, or the loosening of rules that accompanies it. Partisanship means that if Democrats say something is crooked, MAGA types conclude that it must be fine. The other side has enough examples of grubbiness—think of how President Joe Biden’s family took advantage of his position, or the Clinton Foundation received money from Qatar—to make what Mr Trump is doing seem different only in degree.

That is mistaken. And to assume partisanship gives unlimited permission to abuse or suspend rules is too pessimistic. Good-governance reforms have followed each era of excess: the Federal Corrupt Practices Act after the Gilded Age, the Ethics in Government Act after Watergate. Ten years ago a man ran for president denouncing Washington insiders and promising to drain the swamp. That is still one of the great themes in American politics, much more persuasive than warning that liberal democracy is under threat. The president has given his opponents a solid-gold opportunity to use it. ■

Leaders | Time for a pause

Why governments should stop raising the minimum wage

After a decade of rises, there are now far better tools for fighting poverty

Illustration: Simon Bailly

Nov 20th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

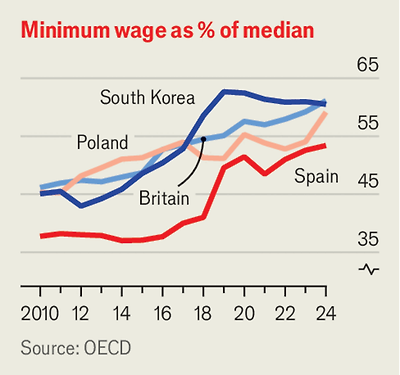

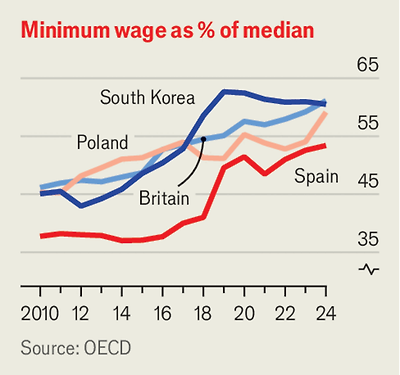

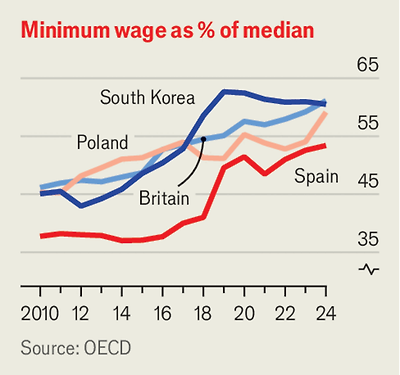

It is easy to see why politicians like raising the minimum wage. Short of cash yet keen to fight inequality, they have seized on a tool of redistribution that costs governments little and wins votes. In its budget on November 26th Britain is likely to raise the minimum wage, which sits at 61% of median income, up from 48% a decade ago. Germany introduced a minimum wage only in 2015; by 2023 it had crossed 50%. And although America’s federal rate of $7.25 an hour has not changed since 2009, many states and cities controlled by Democrats have raised their pay floors far higher. The average effective minimum wage is around $12 per hour; the highest is over $21.

Chart: The Economist

In one respect the surging minimum wage is a triumph for economists. Having originally been sceptics, they embraced the policy around the turn of the millennium, arguing that wage floors did not eliminate jobs as they once feared—a finding that the experience of the past two decades seemed to confirm. Yet as we report this week, just as governments are championing the consensus, scholars are getting cold feet. A growing body of research suggests that minimum wages distort economies in ways that do not immediately appear in jobs numbers.

Dig deeper

Economists get cold feet about high minimum wages

One worry is that it takes time for minimum wages to kill jobs. Evidence from a big hike to Seattle’s pay floor in 2015 and 2016 suggests hiring at the bottom end of the labour market slowed by 10%, even though existing workers were typically not laid off. Another is that higher minimums degrade jobs rather than destroy them. When employers must pay more, but can still hire easily, they may cut corners elsewhere. New research finds that big increases in the minimum wage are associated with shorter or less predictable working hours, more workplace accidents and fewer perks such as health insurance.

A final risk is that early success breeds overconfidence. Moderate minimum wages can, counterintuitively, make jobs more abundant, by offsetting the bargaining power of big employers, who would otherwise restrain hiring to suppress pay. But the more governments embrace big hikes, the more likely they are to eliminate jobs—just as a big enough tax rise will reduce revenue. One recent peer-reviewed estimate puts the average American minimum wage that corrects for employer market power at under $8.

Beyond that, the minimum wage is a crude and wasteful tool for redistribution. Many minimum-wage workers are not poor, but live with higher earners. And when firms raise prices to offset their steeper costs, it is the poor who suffer most—more so than from sales taxes, according to one paper.

Politicians should beware these effects. Although raising minimum wages invariably polls well, electorates everywhere are also angry about soaring prices and a crisis of affordability. There is a danger of a doom loop in which employers’ higher costs are passed on to consumers, making life still less affordable, including for the very workers governments are trying to help. Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York, has promised to raise the minimum wage from $16.50 today to $30 by 2030. Prices would rise significantly as a result, making an already expensive place to live even dearer.

There are better ways to help low earners. In-work tax credits are better targeted towards the poor and, if paid for with growth-friendly taxes, less harmful to the economy. They may lack the appeal of minimum wages, the costs of which are well hidden. But after a decade of aggressive increases, the responsible option is not to go higher still. It is to stop. ■

Asia | Banyan

To glimpse Indonesia’s future, look to its president’s view of the past

Why Prabowo Subianto is rehabilitating the late Suharto

Illustration: Lan Truong

Nov 20th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

AS THE ASIAN financial crisis swept through Indonesia in 1997, the IMF offered the country a bail-out. It was thought that the loan would help Indonesia to turn the page quickly. After all, Suharto, the dictator since 1967, had long appointed capable (often American-educated) technocrats to run the economy, and the result had been three decades of rapid development.

It had also been a long period of enrichment for Suharto, his family members and his cronies as they reached ever deeper into business, finance and the running of the state and the armed forces. Among other things, the crisis laid bare the extent to which this group had abused the financial system. Despite pleas from the IMF, regulators refused to crack down on corruption. The confidence of foreign investors, once strong, collapsed in early 1998, reversing decades of economic growth, and 36m Indonesians fell back into poverty. Amid protest, unrest and blood-letting, Suharto stepped down.

His departure marked the start of the current, generally happier, era in Indonesia: reformasi, or the country’s transition to democracy. And so it is notable, and worrying, that on November 10th the sitting president, Prabowo Subianto, formally elevated the late Suharto to the pantheon of national heroes.

The move was not unexpected. Mr Prabowo served as the commander of the crack special forces in Suharto’s army. He was, indeed, once married to Suharto’s daughter.

Yet there is more to Mr Prabowo’s move than a simple whitewashing of the Suharto era. On the same day as Suharto’s beatification, the president named several of the dictator’s opponents national heroes as well. One is the late Abdurrahman Wahid, or Gus Dur, a nearly blind cleric who led opposition to Suharto’s regime and who was elected president in the first free polls of the post-Suharto years. Another is Marsinah, a labour activist; she was murdered (and her body mutilated) in 1993. None of the soldiers thought responsible has been brought to justice. At a ceremony in the presidential palace in Jakarta, Mr Prabowo handed medals to next-of-kin while the portraits of Gus Dur and Marsinah stood witness.

Mr Prabowo’s backers argue that a spirit of reconciliation is behind his big-tent approach to Indonesia’s history—they note it could have been a matter of just rehabilitating his late father-in-law. Yet his simultaneous honouring of Suharto’s opponents makes the approach far more corrosive than whitewash. By elevating both those who fought for democracy and those who fought to suppress it, Mr Prabowo is in effect flattening Indonesian history, rendering it at best as a kind of bas-relief. In Mr Prabowo’s particular topography of 20th-century Indonesia, there are no persons of particular moral prominence. All struggles, whether for good or for ill, are honoured alike.

A flattened version of history certainly plays to Mr Prabowo’s advantage. His Suharto-era career is littered with abuses. In the final months of Suharto’s rule, as students poured onto the streets in outrage over the first family’s venality, at least nine of their leaders disappeared, kidnapped and tortured by Mr Prabowo’s troops. Mr Prabowo later acknowledged ordering their kidnapping but says they were unharmed—two, his defenders note, even serve as deputy ministers in his administration. But in a separate drive, 13 student activists disappeared and were never heard from again. Mr Prabowo says he knows nothing about those cases. But before he was sworn in as president, his party quietly offered the families of some of the victims around $60,000 each. What was not offered was justice for the killers.

As for Suharto, he never even had to answer for his rule’s original sin in 1965-66: the killing of hundreds of thousands of suspected communist sympathisers on his path to power. One of Suharto’s top lieutenants in the massacres, Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, was also named a national hero this month.

Most troubling, these moves are not just about the past. The president calls for a governing coalition of all Indonesia’s political parties, and has shown that he is willing to use legal coercion to achieve it. All parties would be present in government, but accountability would not. Mr Prabowo might, he muses, even make such a coalition “permanent”. That would amount to a return to the authoritarian politics of the Suharto era. Mr Prabowo’s move to rehabilitate the late dictator says as much about his plans for the future as it does about the past. ■

China | Big lenders

The charts that show how much money China lends to the rich world

Many of the loans look harmless. But some are raising eyebrows

Photograph: AP

Nov 20th 2025|Hong Kong|4 min read

Listen to this story

CHINA HAS become one of the world’s biggest bankers and donors. But its financial influence overseas is hard to track. Its government has a “transparency allergy”, says Brad Parks of AidData, a research centre at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. In 2009 he and his colleagues tried to persuade China’s Ministry of Commerce to open up a bit. “Don’t you want the world to know how generous you are?” they asked. The ministry was unmoved. “Everyone who needs to know how generous we are already knows,” it said.

The researchers, therefore, took a different tack. They scoured media reports for news of loans and grants from China’s government and its state-owned creditors. They also tapped official sources in borrowing countries and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. They have previously published their findings on Chinese financing to developing countries. On November 18th they released a report on its aid and lending to the whole world. The new database covers more than 30,000 projects from 2000 to 2023. It spans rich and poor countries; and private, as well as sovereign, borrowers.

Dig deeper

Four charts show how much money China lends to the rich world

On borrowed dime

China’s financial commitments over that period amount to $2.17trn (adjusted for inflation), an enormous sum. Of that total, only 6% qualifies as aid (either grants or cheap loans). Another 3% is hard to classify one way or the other, given the paucity of information available. Poor countries borrowed another $1.02trn (47% of the total) from state-owned creditors (see chart 1). And high-income countries took the rest (43%). The biggest single borrower, receiving $202bn, was America.

Chart: The Economist

A surprisingly small amount of this money relates to the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a global lending and investment scheme championed by Xi Jinping, China’s leader. Loans for infrastructure under the BRI accounted for only 20% of total Chinese credit in the decade after the initiative was launched in 2013. The BRI was spearheaded by China’s state-directed “policy banks”, such as China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China. But they have become less prominent creditors in recent years, as Chinese lending to poor countries has receded.

Chart: The Economist

That has cleared the stage for China’s massive commercial banks, such as ICBC or Bank of China. Owned by the government, but keen to make a profit, they were responsible for about 60% of all lending by China’s state-owned creditors from 2019 to 2023 (see chart 2). In high-income countries, perhaps their more natural habitat, they accounted for more than 80% of such lending.

Many of these loans look harmless enough. Lenders such as ICBC or Bank of China have followed their clients abroad, setting up subsidiaries in the world’s richest markets. They also chip in to syndicated loans alongside other global banks. In 2012 Bank of China joined JPMorgan Chase and others in making the first of several syndicated loans to Disney.

Sometimes they are just “banks doing what banks do”, says Mr Parks. Other lending, however, raises more eyebrows. A growing share of credit for acquisitions is directed towards 17 industries that governments tend to deem “sensitive”, such as telecoms infrastructure, microprocessors and companies that collect personal data. In 2015, for example, four Chinese state-owned commercial banks provided a loan to Fosun, a Chinese multinational, to help it buy Ironshore, which sold liability insurance through its American subsidiary to officials at the CIA and FBI.

How do AidData’s figures compare with other estimates of Chinese lending? According to China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the stock of loans at the end of 2023 was $805bn, plus another $644bn in trade finance. But these official figures are not directly comparable with the AidData numbers. They exclude credit extended by the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese banks and leave out loans that finance foreign direct investment, which is recorded separately. The official figures also represent the stock of loans that remained outstanding at the end of 2023, whereas AidData have added up the flow of credit over the preceding 24 years.

Mr Parks and his team may also have identified loans that even China’s authorities struggle to track. Their database spans over 1,100 lenders and donors. Although they are all owned by the Chinese state, its ministries do not have “full visibility on what all these different banks are doing”, he explains. He and his team have, on more than one occasion, discovered that Chinese officials sometimes use the AidData figures in their own work. “Having a one-stop shop where they can get all this information is too convenient to pass up,” Mr Parks reckons. Not even the Chinese government always knows exactly how generous it has been. ■

United States | Transparency in government

Release the Epstein files!

What Congress has actually voted to make public

Photograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|WASHINGTON, DC|2 min read

Listen to this story

It is the scandal that will never die. For more than six years the case of Jeffrey Epstein, a dead sex offender with links to the president and other prominent figures, has spawned a dizzying array of conspiracy theories. On November 18th American lawmakers passed a law compelling the government to release its files on Epstein. The bill has been signed by the president. Yet what exactly are the Epstein files, and what can the public expect to see?

The largest batch is held by the Department of Justice (DoJ) and encompasses two criminal investigations that unfolded between 2006 and 2019. The first involved charges that Epstein abused dozens of underage girls in Florida. That case led to a controversial plea deal in 2008. Other DoJ files accumulated during a second investigation that did result in a trafficking charge in July 2019. The department also holds information about Epstein’s apparent suicide the following month while in federal custody.

Federal agents amassed documents from property seizures as well as detailed witness interviews. A July memo from the DoJ noted that it had some 300 gigabytes of data and physical evidence, which included a large volume of images and videos of Epstein’s victims. The files also contain reams of internal DoJ communications.

Yet the narrow focus of the criminal investigations may disappoint those expecting damning new revelations about Epstein’s associates. “What’s crucial [in these cases] is what happened to the women, and not what people happen to be connected to Epstein,” says Jeremy Paul, a law professor at Northeastern University.

If the DoJ files are released, information about Epstein’s victims is likely to be extensively redacted. The DoJ can also withhold any documents that could jeopardise ongoing investigations. (Mr Trump recently ordered the department to investigate prominent Democrats associated with Epstein.) For those podcasters and politicians who believe withholding documents is evidence of conspiracy, there will be plenty to talk about. ■

United States | Learning like the ancients

AI is accelerating a tech backlash in American classrooms

Handwritten and oral exams are making a comeback

The latest in edtechPhotograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|NEW YORK|5 min read

Listen to this story

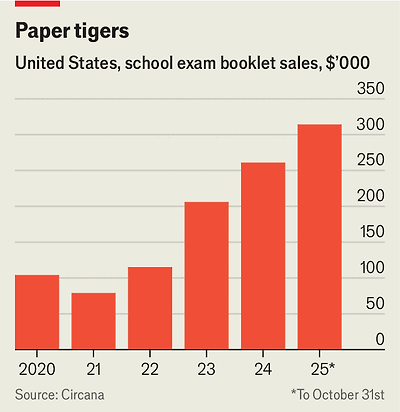

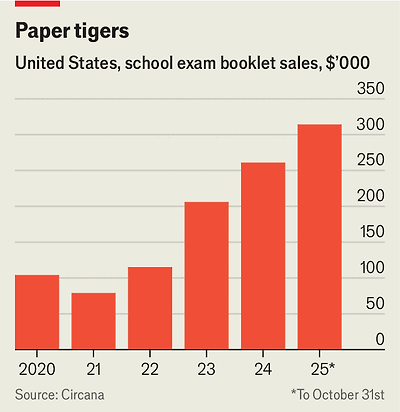

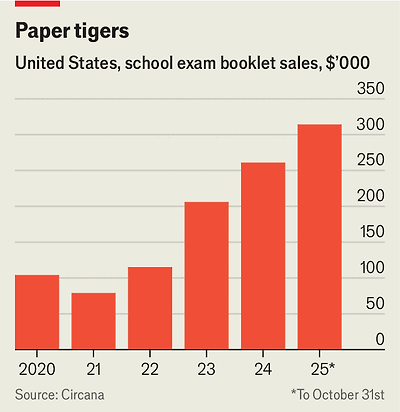

Acentury and a half before Apple marketed iPads to schools, in 1857, a Greek-born Harvard professor, Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, held a bonfire of newly introduced “blue books”, bound exam booklets for pen-and-paper tests that (to his ire) were to replace oral recitations. He lost. These booklets would torment generations of American students before yielding in turn to computerised testing. But now the blue book is making a comeback, with booklet sales more than doubling from 2022 to 2024 (see chart), according to Circana, a data firm. And oral exams appear ripe for revival, too.

From high school to university, teachers are playing defence against classroom tech that enables cheating and foments distraction. Laura Lomas, a literature professor at Rutgers University, now requires students to attend a play whose ending changes every night, so she knows if they were there. She assigns oral presentations rather than more AI-friendly PowerPoints, and allows no bathroom breaks during blue-book exams so students can’t peek at their phones. Sara Brock, a high-school English teacher in Port Washington, New York, requires students to write exercises by hand in class. Justin Reich, director of the MIT Teaching Systems Lab, says his daughter’s middle school has “more or less given up on [assigning] homework other than math.” Students are told to read instead.

Chart: The Economist

Such retrenchments are likely to keep spreading. In a 2023 survey by Intelligent, a research outfit, 66% of high-school and college instructors said they were changing assignments because of ChatGPT; of those changing, 76% required or planned to require handwritten work. And 87% said they require or plan to add an oral presentation component. A survey the same year by EdWeek Research Centre found that 43% of educators think students should solve maths problems in class using pencil and paper to show they are not using AI. And in a Stanford University pilot programme, proctors—how quaint!—prowl classrooms to monitor test-taking.

The battle for and against classroom tech in America is raging in other rich countries, notes Isabel Dans Álvarez de Sotomayor, an education scholar at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. As poorer countries race to digitise, richer countries are restricting classroom tech even as they invest in more digital infrastructure. After initially going all-in on technology, in 2023 Sweden banned digital tools for young children and now emphasises physical textbooks, handwriting and reading. Schools in Denmark and Finland are on the same page.

The reason is not just ChatGPT and the mass cheating it makes possible. Teachers are worried about mass distraction as well. In 2025 56% of educators said laptops, tablets or desktops are a major source of diverted attention, according to another EdWeek Research Centre survey. At Bowdoin College, a private liberal-arts college in Maine, the dean says that “many faculty had already marked their classrooms as, for the most part, device-free spaces” even before “the recent ubiquity of AI”.

Cheating is nothing new—in a study ten years ago, 87% of high-school students admitted to cheating at least once the month before, and the researchers found that percentage has actually come down since—but the “magnitude of cheating is substantially different” since advanced AI arrived, says Mr Reich of MIT. “We have a zillion interviews with kids of all kinds who say things like, ‘In my senior year [of high school] I never did homework. Every assignment I did used generative AI.’” The college level is no better, says Ms Lomas. “One student even quoted a paper by me that AI made up out of thin air”.

Rigorous studies have shown that classroom tech can help pupils learn algebra, but evidence of improved outcomes in other areas is thin. By contrast, the benefits handwriting offers for cognition are gaining new respect, even beyond the humanities. A computer science teacher at Hunter College High School in New York recently reinstituted handwriting for coding assignments because it helps with retention as well as critical thinking.

But not everyone who wants to go old-school can. Parents often can’t easily opt out of edtech. And Derek Vaillant, a history professor at the University of Michigan, says that while there is a consensus that teachers need to “get back to basics” by prioritising original, in-person, pen-and-paper exams, large public universities are not providing resources commensurate with the challenge by hiring enough teaching assistants. Administrators are “speaking out of both sides of their mouths”.

Among parents, it is the affluent and educated who want less tech in the classroom, says Anne Maheux of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who studies adolescent tech use. A Pew Research Centre report in December 2024 found that 58% of Hispanic and 53% of black teenagers reported being on the internet almost constantly, compared with 37% of white teenagers. The digital divide, she notes, has flipped.

The changes require rethinking the purpose of time in the classroom. At Hunter, an 11th-grade English teacher assigned five literature responses to be written by hand, each taking up a whole period. In the past that was not considered a good use of a teacher’s effort, says Mr Reich. But today, with digital “heat-seeking missiles” soaking up attention, “maybe the best thing we can do in the classroom is give young people the gift of quiet, undistracted time.”■

The Americas | War and peace

Is Donald Trump preparing to strike Venezuela or lining up a deal?

The answer is both

Photograph: Shutterstock

Nov 19th 2025|Caracas and Washington, DC|3 min read

Listen to this story

What does Donald Trump want from Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s strongman? As the uss Gerald R. Ford, a giant aircraft-carrier, entered the Caribbean on November 16th the administration said it would designate the Cartel de los Soles, which it alleges is headed by Mr Maduro, as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation (fto)—with effect from November 24th. Mr Trump has refused to rule out the use of force, even leaving open the possibility of a ground invasion; yet at the same time he has floated the idea of talks. “We may be having some discussions with Maduro,” he said. In response Mr Maduro, who stole last year’s presidential election, said he would be willing to talk “face to face, without any problem”.

A deal that would sate the Trump administration and leave Mr Maduro in power is difficult to imagine; so is Mr Maduro voluntarily stepping down. Much depends on what Mr Trump thinks is the best way to get a headline-grabbing win: a deal secured through gunboat intimidation, or dramatic but limited strikes to unseat—or even kill—Mr Maduro.

Read a guest essay by María Corina Machado, Venezuela’s opposition leader and Nobel peace laureate, on why time is running out for Nicolás Maduro

The fto designation bolsters both the political and perhaps the legal case for strikes in Venezuela. It frames what is essentially a campaign for regime change as a counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics operation, says Brian Finucane of International Crisis Group, a think-tank. Earlier this month the administration is said to have told Congress that it lacked the legal authority to strike Venezuela. Now Mr Trump is implying that the new designation allows him to do just that. Plenty disagree. “The designation means nothing under international law,” says Mary Ellen O’Connell of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

There is little evidence that the Cartel de los Soles is an organised gang run by Mr Maduro, though parts of the Venezuelan armed forces are involved in drug trafficking. Still, the designation will make it a crime to provide money or services to the group. That could affect foreign firms that do business with the Venezuelan state. The administration has conspicuously refrained from declaring Venezuela a state sponsor of terrorism, which is the bigger worry for companies such as Chevron, an American oil giant.

What any deal might look like remains unclear. A well-placed businessman says the regime doubts Mr Trump will send in the troops. That might limit how much Mr Maduro is willing to concede. Still, in secret negotiations earlier this year the dictator is said to have offered the United States sweeping access to Venezuela’s oil and minerals. He may also be tempted to hand over some top brass as drug-trafficking scapegoats, too. Some American officials would surely demand any deal remove Mr Maduro from power. Yet because they insist their focus is drug interdiction, not restoring democracy, that could leave one of his cronies in charge.

Mr Trump is unpredictable. He ordered strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities in June, as talks continued. He could leave his armada in the Caribbean, striking only alleged drug boats or menacing others. He recently said he “would be proud” to bomb drug gangs in other countries, such as Mexico and Colombia. Alas, of the possible scenarios, very few include what most Venezuelans voted for last year: a democratic country without Mr Maduro. ■

Leaders | Time for a pause

Why governments should stop raising the minimum wage

After a decade of rises, there are now far better tools for fighting poverty

Illustration: Simon Bailly

Nov 20th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

It is easy to see why politicians like raising the minimum wage. Short of cash yet keen to fight inequality, they have seized on a tool of redistribution that costs governments little and wins votes. In its budget on November 26th Britain is likely to raise the minimum wage, which sits at 61% of median income, up from 48% a decade ago. Germany introduced a minimum wage only in 2015; by 2023 it had crossed 50%. And although America’s federal rate of $7.25 an hour has not changed since 2009, many states and cities controlled by Democrats have raised their pay floors far higher. The average effective minimum wage is around $12 per hour; the highest is over $21.

Chart: The Economist

In one respect the surging minimum wage is a triumph for economists. Having originally been sceptics, they embraced the policy around the turn of the millennium, arguing that wage floors did not eliminate jobs as they once feared—a finding that the experience of the past two decades seemed to confirm. Yet as we report this week, just as governments are championing the consensus, scholars are getting cold feet. A growing body of research suggests that minimum wages distort economies in ways that do not immediately appear in jobs numbers.

Dig deeper

Economists get cold feet about high minimum wages

One worry is that it takes time for minimum wages to kill jobs. Evidence from a big hike to Seattle’s pay floor in 2015 and 2016 suggests hiring at the bottom end of the labour market slowed by 10%, even though existing workers were typically not laid off. Another is that higher minimums degrade jobs rather than destroy them. When employers must pay more, but can still hire easily, they may cut corners elsewhere. New research finds that big increases in the minimum wage are associated with shorter or less predictable working hours, more workplace accidents and fewer perks such as health insurance.

A final risk is that early success breeds overconfidence. Moderate minimum wages can, counterintuitively, make jobs more abundant, by offsetting the bargaining power of big employers, who would otherwise restrain hiring to suppress pay. But the more governments embrace big hikes, the more likely they are to eliminate jobs—just as a big enough tax rise will reduce revenue. One recent peer-reviewed estimate puts the average American minimum wage that corrects for employer market power at under $8.

Beyond that, the minimum wage is a crude and wasteful tool for redistribution. Many minimum-wage workers are not poor, but live with higher earners. And when firms raise prices to offset their steeper costs, it is the poor who suffer most—more so than from sales taxes, according to one paper.

Politicians should beware these effects. Although raising minimum wages invariably polls well, electorates everywhere are also angry about soaring prices and a crisis of affordability. There is a danger of a doom loop in which employers’ higher costs are passed on to consumers, making life still less affordable, including for the very workers governments are trying to help. Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York, has promised to raise the minimum wage from $16.50 today to $30 by 2030. Prices would rise significantly as a result, making an already expensive place to live even dearer.

There are better ways to help low earners. In-work tax credits are better targeted towards the poor and, if paid for with growth-friendly taxes, less harmful to the economy. They may lack the appeal of minimum wages, the costs of which are well hidden. But after a decade of aggressive increases, the responsible option is not to go higher still. It is to stop. ■

Asia | Banyan

To glimpse Indonesia’s future, look to its president’s view of the past

Why Prabowo Subianto is rehabilitating the late Suharto

Illustration: Lan Truong

Nov 20th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

AS THE ASIAN financial crisis swept through Indonesia in 1997, the IMF offered the country a bail-out. It was thought that the loan would help Indonesia to turn the page quickly. After all, Suharto, the dictator since 1967, had long appointed capable (often American-educated) technocrats to run the economy, and the result had been three decades of rapid development.

It had also been a long period of enrichment for Suharto, his family members and his cronies as they reached ever deeper into business, finance and the running of the state and the armed forces. Among other things, the crisis laid bare the extent to which this group had abused the financial system. Despite pleas from the IMF, regulators refused to crack down on corruption. The confidence of foreign investors, once strong, collapsed in early 1998, reversing decades of economic growth, and 36m Indonesians fell back into poverty. Amid protest, unrest and blood-letting, Suharto stepped down.

His departure marked the start of the current, generally happier, era in Indonesia: reformasi, or the country’s transition to democracy. And so it is notable, and worrying, that on November 10th the sitting president, Prabowo Subianto, formally elevated the late Suharto to the pantheon of national heroes.

The move was not unexpected. Mr Prabowo served as the commander of the crack special forces in Suharto’s army. He was, indeed, once married to Suharto’s daughter.

Yet there is more to Mr Prabowo’s move than a simple whitewashing of the Suharto era. On the same day as Suharto’s beatification, the president named several of the dictator’s opponents national heroes as well. One is the late Abdurrahman Wahid, or Gus Dur, a nearly blind cleric who led opposition to Suharto’s regime and who was elected president in the first free polls of the post-Suharto years. Another is Marsinah, a labour activist; she was murdered (and her body mutilated) in 1993. None of the soldiers thought responsible has been brought to justice. At a ceremony in the presidential palace in Jakarta, Mr Prabowo handed medals to next-of-kin while the portraits of Gus Dur and Marsinah stood witness.

Mr Prabowo’s backers argue that a spirit of reconciliation is behind his big-tent approach to Indonesia’s history—they note it could have been a matter of just rehabilitating his late father-in-law. Yet his simultaneous honouring of Suharto’s opponents makes the approach far more corrosive than whitewash. By elevating both those who fought for democracy and those who fought to suppress it, Mr Prabowo is in effect flattening Indonesian history, rendering it at best as a kind of bas-relief. In Mr Prabowo’s particular topography of 20th-century Indonesia, there are no persons of particular moral prominence. All struggles, whether for good or for ill, are honoured alike.

A flattened version of history certainly plays to Mr Prabowo’s advantage. His Suharto-era career is littered with abuses. In the final months of Suharto’s rule, as students poured onto the streets in outrage over the first family’s venality, at least nine of their leaders disappeared, kidnapped and tortured by Mr Prabowo’s troops. Mr Prabowo later acknowledged ordering their kidnapping but says they were unharmed—two, his defenders note, even serve as deputy ministers in his administration. But in a separate drive, 13 student activists disappeared and were never heard from again. Mr Prabowo says he knows nothing about those cases. But before he was sworn in as president, his party quietly offered the families of some of the victims around $60,000 each. What was not offered was justice for the killers.

As for Suharto, he never even had to answer for his rule’s original sin in 1965-66: the killing of hundreds of thousands of suspected communist sympathisers on his path to power. One of Suharto’s top lieutenants in the massacres, Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, was also named a national hero this month.

Most troubling, these moves are not just about the past. The president calls for a governing coalition of all Indonesia’s political parties, and has shown that he is willing to use legal coercion to achieve it. All parties would be present in government, but accountability would not. Mr Prabowo might, he muses, even make such a coalition “permanent”. That would amount to a return to the authoritarian politics of the Suharto era. Mr Prabowo’s move to rehabilitate the late dictator says as much about his plans for the future as it does about the past. ■

China | Big lenders

The charts that show how much money China lends to the rich world

Many of the loans look harmless. But some are raising eyebrows

Photograph: AP

Nov 20th 2025|Hong Kong|4 min read

Listen to this story

CHINA HAS become one of the world’s biggest bankers and donors. But its financial influence overseas is hard to track. Its government has a “transparency allergy”, says Brad Parks of AidData, a research centre at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. In 2009 he and his colleagues tried to persuade China’s Ministry of Commerce to open up a bit. “Don’t you want the world to know how generous you are?” they asked. The ministry was unmoved. “Everyone who needs to know how generous we are already knows,” it said.

The researchers, therefore, took a different tack. They scoured media reports for news of loans and grants from China’s government and its state-owned creditors. They also tapped official sources in borrowing countries and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. They have previously published their findings on Chinese financing to developing countries. On November 18th they released a report on its aid and lending to the whole world. The new database covers more than 30,000 projects from 2000 to 2023. It spans rich and poor countries; and private, as well as sovereign, borrowers.

Dig deeper

Four charts show how much money China lends to the rich world

On borrowed dime

China’s financial commitments over that period amount to $2.17trn (adjusted for inflation), an enormous sum. Of that total, only 6% qualifies as aid (either grants or cheap loans). Another 3% is hard to classify one way or the other, given the paucity of information available. Poor countries borrowed another $1.02trn (47% of the total) from state-owned creditors (see chart 1). And high-income countries took the rest (43%). The biggest single borrower, receiving $202bn, was America.

Chart: The Economist

A surprisingly small amount of this money relates to the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a global lending and investment scheme championed by Xi Jinping, China’s leader. Loans for infrastructure under the BRI accounted for only 20% of total Chinese credit in the decade after the initiative was launched in 2013. The BRI was spearheaded by China’s state-directed “policy banks”, such as China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China. But they have become less prominent creditors in recent years, as Chinese lending to poor countries has receded.

Chart: The Economist

That has cleared the stage for China’s massive commercial banks, such as ICBC or Bank of China. Owned by the government, but keen to make a profit, they were responsible for about 60% of all lending by China’s state-owned creditors from 2019 to 2023 (see chart 2). In high-income countries, perhaps their more natural habitat, they accounted for more than 80% of such lending.

Many of these loans look harmless enough. Lenders such as ICBC or Bank of China have followed their clients abroad, setting up subsidiaries in the world’s richest markets. They also chip in to syndicated loans alongside other global banks. In 2012 Bank of China joined JPMorgan Chase and others in making the first of several syndicated loans to Disney.

Sometimes they are just “banks doing what banks do”, says Mr Parks. Other lending, however, raises more eyebrows. A growing share of credit for acquisitions is directed towards 17 industries that governments tend to deem “sensitive”, such as telecoms infrastructure, microprocessors and companies that collect personal data. In 2015, for example, four Chinese state-owned commercial banks provided a loan to Fosun, a Chinese multinational, to help it buy Ironshore, which sold liability insurance through its American subsidiary to officials at the CIA and FBI.

How do AidData’s figures compare with other estimates of Chinese lending? According to China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the stock of loans at the end of 2023 was $805bn, plus another $644bn in trade finance. But these official figures are not directly comparable with the AidData numbers. They exclude credit extended by the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese banks and leave out loans that finance foreign direct investment, which is recorded separately. The official figures also represent the stock of loans that remained outstanding at the end of 2023, whereas AidData have added up the flow of credit over the preceding 24 years.

Mr Parks and his team may also have identified loans that even China’s authorities struggle to track. Their database spans over 1,100 lenders and donors. Although they are all owned by the Chinese state, its ministries do not have “full visibility on what all these different banks are doing”, he explains. He and his team have, on more than one occasion, discovered that Chinese officials sometimes use the AidData figures in their own work. “Having a one-stop shop where they can get all this information is too convenient to pass up,” Mr Parks reckons. Not even the Chinese government always knows exactly how generous it has been. ■

United States | Transparency in government

Release the Epstein files!

What Congress has actually voted to make public

Photograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|WASHINGTON, DC|2 min read

Listen to this story

It is the scandal that will never die. For more than six years the case of Jeffrey Epstein, a dead sex offender with links to the president and other prominent figures, has spawned a dizzying array of conspiracy theories. On November 18th American lawmakers passed a law compelling the government to release its files on Epstein. The bill has been signed by the president. Yet what exactly are the Epstein files, and what can the public expect to see?

The largest batch is held by the Department of Justice (DoJ) and encompasses two criminal investigations that unfolded between 2006 and 2019. The first involved charges that Epstein abused dozens of underage girls in Florida. That case led to a controversial plea deal in 2008. Other DoJ files accumulated during a second investigation that did result in a trafficking charge in July 2019. The department also holds information about Epstein’s apparent suicide the following month while in federal custody.

Federal agents amassed documents from property seizures as well as detailed witness interviews. A July memo from the DoJ noted that it had some 300 gigabytes of data and physical evidence, which included a large volume of images and videos of Epstein’s victims. The files also contain reams of internal DoJ communications.

Yet the narrow focus of the criminal investigations may disappoint those expecting damning new revelations about Epstein’s associates. “What’s crucial [in these cases] is what happened to the women, and not what people happen to be connected to Epstein,” says Jeremy Paul, a law professor at Northeastern University.

If the DoJ files are released, information about Epstein’s victims is likely to be extensively redacted. The DoJ can also withhold any documents that could jeopardise ongoing investigations. (Mr Trump recently ordered the department to investigate prominent Democrats associated with Epstein.) For those podcasters and politicians who believe withholding documents is evidence of conspiracy, there will be plenty to talk about. ■

United States | Learning like the ancients

AI is accelerating a tech backlash in American classrooms

Handwritten and oral exams are making a comeback

The latest in edtechPhotograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|NEW YORK|5 min read

Listen to this story

Acentury and a half before Apple marketed iPads to schools, in 1857, a Greek-born Harvard professor, Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, held a bonfire of newly introduced “blue books”, bound exam booklets for pen-and-paper tests that (to his ire) were to replace oral recitations. He lost. These booklets would torment generations of American students before yielding in turn to computerised testing. But now the blue book is making a comeback, with booklet sales more than doubling from 2022 to 2024 (see chart), according to Circana, a data firm. And oral exams appear ripe for revival, too.

From high school to university, teachers are playing defence against classroom tech that enables cheating and foments distraction. Laura Lomas, a literature professor at Rutgers University, now requires students to attend a play whose ending changes every night, so she knows if they were there. She assigns oral presentations rather than more AI-friendly PowerPoints, and allows no bathroom breaks during blue-book exams so students can’t peek at their phones. Sara Brock, a high-school English teacher in Port Washington, New York, requires students to write exercises by hand in class. Justin Reich, director of the MIT Teaching Systems Lab, says his daughter’s middle school has “more or less given up on [assigning] homework other than math.” Students are told to read instead.

Chart: The Economist

Such retrenchments are likely to keep spreading. In a 2023 survey by Intelligent, a research outfit, 66% of high-school and college instructors said they were changing assignments because of ChatGPT; of those changing, 76% required or planned to require handwritten work. And 87% said they require or plan to add an oral presentation component. A survey the same year by EdWeek Research Centre found that 43% of educators think students should solve maths problems in class using pencil and paper to show they are not using AI. And in a Stanford University pilot programme, proctors—how quaint!—prowl classrooms to monitor test-taking.

The battle for and against classroom tech in America is raging in other rich countries, notes Isabel Dans Álvarez de Sotomayor, an education scholar at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. As poorer countries race to digitise, richer countries are restricting classroom tech even as they invest in more digital infrastructure. After initially going all-in on technology, in 2023 Sweden banned digital tools for young children and now emphasises physical textbooks, handwriting and reading. Schools in Denmark and Finland are on the same page.

The reason is not just ChatGPT and the mass cheating it makes possible. Teachers are worried about mass distraction as well. In 2025 56% of educators said laptops, tablets or desktops are a major source of diverted attention, according to another EdWeek Research Centre survey. At Bowdoin College, a private liberal-arts college in Maine, the dean says that “many faculty had already marked their classrooms as, for the most part, device-free spaces” even before “the recent ubiquity of AI”.

Cheating is nothing new—in a study ten years ago, 87% of high-school students admitted to cheating at least once the month before, and the researchers found that percentage has actually come down since—but the “magnitude of cheating is substantially different” since advanced AI arrived, says Mr Reich of MIT. “We have a zillion interviews with kids of all kinds who say things like, ‘In my senior year [of high school] I never did homework. Every assignment I did used generative AI.’” The college level is no better, says Ms Lomas. “One student even quoted a paper by me that AI made up out of thin air”.

Rigorous studies have shown that classroom tech can help pupils learn algebra, but evidence of improved outcomes in other areas is thin. By contrast, the benefits handwriting offers for cognition are gaining new respect, even beyond the humanities. A computer science teacher at Hunter College High School in New York recently reinstituted handwriting for coding assignments because it helps with retention as well as critical thinking.

But not everyone who wants to go old-school can. Parents often can’t easily opt out of edtech. And Derek Vaillant, a history professor at the University of Michigan, says that while there is a consensus that teachers need to “get back to basics” by prioritising original, in-person, pen-and-paper exams, large public universities are not providing resources commensurate with the challenge by hiring enough teaching assistants. Administrators are “speaking out of both sides of their mouths”.

Among parents, it is the affluent and educated who want less tech in the classroom, says Anne Maheux of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who studies adolescent tech use. A Pew Research Centre report in December 2024 found that 58% of Hispanic and 53% of black teenagers reported being on the internet almost constantly, compared with 37% of white teenagers. The digital divide, she notes, has flipped.

The changes require rethinking the purpose of time in the classroom. At Hunter, an 11th-grade English teacher assigned five literature responses to be written by hand, each taking up a whole period. In the past that was not considered a good use of a teacher’s effort, says Mr Reich. But today, with digital “heat-seeking missiles” soaking up attention, “maybe the best thing we can do in the classroom is give young people the gift of quiet, undistracted time.”■

The Americas | War and peace

Is Donald Trump preparing to strike Venezuela or lining up a deal?

The answer is both

Photograph: Shutterstock

Nov 19th 2025|Caracas and Washington, DC|3 min read

Listen to this story

What does Donald Trump want from Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s strongman? As the uss Gerald R. Ford, a giant aircraft-carrier, entered the Caribbean on November 16th the administration said it would designate the Cartel de los Soles, which it alleges is headed by Mr Maduro, as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation (fto)—with effect from November 24th. Mr Trump has refused to rule out the use of force, even leaving open the possibility of a ground invasion; yet at the same time he has floated the idea of talks. “We may be having some discussions with Maduro,” he said. In response Mr Maduro, who stole last year’s presidential election, said he would be willing to talk “face to face, without any problem”.

A deal that would sate the Trump administration and leave Mr Maduro in power is difficult to imagine; so is Mr Maduro voluntarily stepping down. Much depends on what Mr Trump thinks is the best way to get a headline-grabbing win: a deal secured through gunboat intimidation, or dramatic but limited strikes to unseat—or even kill—Mr Maduro.

Read a guest essay by María Corina Machado, Venezuela’s opposition leader and Nobel peace laureate, on why time is running out for Nicolás Maduro

The fto designation bolsters both the political and perhaps the legal case for strikes in Venezuela. It frames what is essentially a campaign for regime change as a counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics operation, says Brian Finucane of International Crisis Group, a think-tank. Earlier this month the administration is said to have told Congress that it lacked the legal authority to strike Venezuela. Now Mr Trump is implying that the new designation allows him to do just that. Plenty disagree. “The designation means nothing under international law,” says Mary Ellen O’Connell of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

There is little evidence that the Cartel de los Soles is an organised gang run by Mr Maduro, though parts of the Venezuelan armed forces are involved in drug trafficking. Still, the designation will make it a crime to provide money or services to the group. That could affect foreign firms that do business with the Venezuelan state. The administration has conspicuously refrained from declaring Venezuela a state sponsor of terrorism, which is the bigger worry for companies such as Chevron, an American oil giant.

What any deal might look like remains unclear. A well-placed businessman says the regime doubts Mr Trump will send in the troops. That might limit how much Mr Maduro is willing to concede. Still, in secret negotiations earlier this year the dictator is said to have offered the United States sweeping access to Venezuela’s oil and minerals. He may also be tempted to hand over some top brass as drug-trafficking scapegoats, too. Some American officials would surely demand any deal remove Mr Maduro from power. Yet because they insist their focus is drug interdiction, not restoring democracy, that could leave one of his cronies in charge.

Mr Trump is unpredictable. He ordered strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities in June, as talks continued. He could leave his armada in the Caribbean, striking only alleged drug boats or menacing others. He recently said he “would be proud” to bomb drug gangs in other countries, such as Mexico and Colombia. Alas, of the possible scenarios, very few include what most Venezuelans voted for last year: a democratic country without Mr Maduro. ■

Leaders | Time for a pause

Why governments should stop raising the minimum wage

After a decade of rises, there are now far better tools for fighting poverty

Illustration: Simon Bailly

Nov 20th 2025|3 min read

Listen to this story

It is easy to see why politicians like raising the minimum wage. Short of cash yet keen to fight inequality, they have seized on a tool of redistribution that costs governments little and wins votes. In its budget on November 26th Britain is likely to raise the minimum wage, which sits at 61% of median income, up from 48% a decade ago. Germany introduced a minimum wage only in 2015; by 2023 it had crossed 50%. And although America’s federal rate of $7.25 an hour has not changed since 2009, many states and cities controlled by Democrats have raised their pay floors far higher. The average effective minimum wage is around $12 per hour; the highest is over $21.

Chart: The Economist

In one respect the surging minimum wage is a triumph for economists. Having originally been sceptics, they embraced the policy around the turn of the millennium, arguing that wage floors did not eliminate jobs as they once feared—a finding that the experience of the past two decades seemed to confirm. Yet as we report this week, just as governments are championing the consensus, scholars are getting cold feet. A growing body of research suggests that minimum wages distort economies in ways that do not immediately appear in jobs numbers.

Dig deeper

Economists get cold feet about high minimum wages

One worry is that it takes time for minimum wages to kill jobs. Evidence from a big hike to Seattle’s pay floor in 2015 and 2016 suggests hiring at the bottom end of the labour market slowed by 10%, even though existing workers were typically not laid off. Another is that higher minimums degrade jobs rather than destroy them. When employers must pay more, but can still hire easily, they may cut corners elsewhere. New research finds that big increases in the minimum wage are associated with shorter or less predictable working hours, more workplace accidents and fewer perks such as health insurance.

A final risk is that early success breeds overconfidence. Moderate minimum wages can, counterintuitively, make jobs more abundant, by offsetting the bargaining power of big employers, who would otherwise restrain hiring to suppress pay. But the more governments embrace big hikes, the more likely they are to eliminate jobs—just as a big enough tax rise will reduce revenue. One recent peer-reviewed estimate puts the average American minimum wage that corrects for employer market power at under $8.

Beyond that, the minimum wage is a crude and wasteful tool for redistribution. Many minimum-wage workers are not poor, but live with higher earners. And when firms raise prices to offset their steeper costs, it is the poor who suffer most—more so than from sales taxes, according to one paper.

Politicians should beware these effects. Although raising minimum wages invariably polls well, electorates everywhere are also angry about soaring prices and a crisis of affordability. There is a danger of a doom loop in which employers’ higher costs are passed on to consumers, making life still less affordable, including for the very workers governments are trying to help. Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York, has promised to raise the minimum wage from $16.50 today to $30 by 2030. Prices would rise significantly as a result, making an already expensive place to live even dearer.

There are better ways to help low earners. In-work tax credits are better targeted towards the poor and, if paid for with growth-friendly taxes, less harmful to the economy. They may lack the appeal of minimum wages, the costs of which are well hidden. But after a decade of aggressive increases, the responsible option is not to go higher still. It is to stop. ■

Asia | Banyan

To glimpse Indonesia’s future, look to its president’s view of the past

Why Prabowo Subianto is rehabilitating the late Suharto

Illustration: Lan Truong

Nov 20th 2025|4 min read

Listen to this story

AS THE ASIAN financial crisis swept through Indonesia in 1997, the IMF offered the country a bail-out. It was thought that the loan would help Indonesia to turn the page quickly. After all, Suharto, the dictator since 1967, had long appointed capable (often American-educated) technocrats to run the economy, and the result had been three decades of rapid development.

It had also been a long period of enrichment for Suharto, his family members and his cronies as they reached ever deeper into business, finance and the running of the state and the armed forces. Among other things, the crisis laid bare the extent to which this group had abused the financial system. Despite pleas from the IMF, regulators refused to crack down on corruption. The confidence of foreign investors, once strong, collapsed in early 1998, reversing decades of economic growth, and 36m Indonesians fell back into poverty. Amid protest, unrest and blood-letting, Suharto stepped down.

His departure marked the start of the current, generally happier, era in Indonesia: reformasi, or the country’s transition to democracy. And so it is notable, and worrying, that on November 10th the sitting president, Prabowo Subianto, formally elevated the late Suharto to the pantheon of national heroes.

The move was not unexpected. Mr Prabowo served as the commander of the crack special forces in Suharto’s army. He was, indeed, once married to Suharto’s daughter.

Yet there is more to Mr Prabowo’s move than a simple whitewashing of the Suharto era. On the same day as Suharto’s beatification, the president named several of the dictator’s opponents national heroes as well. One is the late Abdurrahman Wahid, or Gus Dur, a nearly blind cleric who led opposition to Suharto’s regime and who was elected president in the first free polls of the post-Suharto years. Another is Marsinah, a labour activist; she was murdered (and her body mutilated) in 1993. None of the soldiers thought responsible has been brought to justice. At a ceremony in the presidential palace in Jakarta, Mr Prabowo handed medals to next-of-kin while the portraits of Gus Dur and Marsinah stood witness.

Mr Prabowo’s backers argue that a spirit of reconciliation is behind his big-tent approach to Indonesia’s history—they note it could have been a matter of just rehabilitating his late father-in-law. Yet his simultaneous honouring of Suharto’s opponents makes the approach far more corrosive than whitewash. By elevating both those who fought for democracy and those who fought to suppress it, Mr Prabowo is in effect flattening Indonesian history, rendering it at best as a kind of bas-relief. In Mr Prabowo’s particular topography of 20th-century Indonesia, there are no persons of particular moral prominence. All struggles, whether for good or for ill, are honoured alike.

A flattened version of history certainly plays to Mr Prabowo’s advantage. His Suharto-era career is littered with abuses. In the final months of Suharto’s rule, as students poured onto the streets in outrage over the first family’s venality, at least nine of their leaders disappeared, kidnapped and tortured by Mr Prabowo’s troops. Mr Prabowo later acknowledged ordering their kidnapping but says they were unharmed—two, his defenders note, even serve as deputy ministers in his administration. But in a separate drive, 13 student activists disappeared and were never heard from again. Mr Prabowo says he knows nothing about those cases. But before he was sworn in as president, his party quietly offered the families of some of the victims around $60,000 each. What was not offered was justice for the killers.

As for Suharto, he never even had to answer for his rule’s original sin in 1965-66: the killing of hundreds of thousands of suspected communist sympathisers on his path to power. One of Suharto’s top lieutenants in the massacres, Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, was also named a national hero this month.

Most troubling, these moves are not just about the past. The president calls for a governing coalition of all Indonesia’s political parties, and has shown that he is willing to use legal coercion to achieve it. All parties would be present in government, but accountability would not. Mr Prabowo might, he muses, even make such a coalition “permanent”. That would amount to a return to the authoritarian politics of the Suharto era. Mr Prabowo’s move to rehabilitate the late dictator says as much about his plans for the future as it does about the past. ■

China | Big lenders

The charts that show how much money China lends to the rich world

Many of the loans look harmless. But some are raising eyebrows

Photograph: AP

Nov 20th 2025|Hong Kong|4 min read

Listen to this story

CHINA HAS become one of the world’s biggest bankers and donors. But its financial influence overseas is hard to track. Its government has a “transparency allergy”, says Brad Parks of AidData, a research centre at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. In 2009 he and his colleagues tried to persuade China’s Ministry of Commerce to open up a bit. “Don’t you want the world to know how generous you are?” they asked. The ministry was unmoved. “Everyone who needs to know how generous we are already knows,” it said.

The researchers, therefore, took a different tack. They scoured media reports for news of loans and grants from China’s government and its state-owned creditors. They also tapped official sources in borrowing countries and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. They have previously published their findings on Chinese financing to developing countries. On November 18th they released a report on its aid and lending to the whole world. The new database covers more than 30,000 projects from 2000 to 2023. It spans rich and poor countries; and private, as well as sovereign, borrowers.

Dig deeper

Four charts show how much money China lends to the rich world

On borrowed dime

China’s financial commitments over that period amount to $2.17trn (adjusted for inflation), an enormous sum. Of that total, only 6% qualifies as aid (either grants or cheap loans). Another 3% is hard to classify one way or the other, given the paucity of information available. Poor countries borrowed another $1.02trn (47% of the total) from state-owned creditors (see chart 1). And high-income countries took the rest (43%). The biggest single borrower, receiving $202bn, was America.

Chart: The Economist

A surprisingly small amount of this money relates to the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a global lending and investment scheme championed by Xi Jinping, China’s leader. Loans for infrastructure under the BRI accounted for only 20% of total Chinese credit in the decade after the initiative was launched in 2013. The BRI was spearheaded by China’s state-directed “policy banks”, such as China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China. But they have become less prominent creditors in recent years, as Chinese lending to poor countries has receded.

Chart: The Economist

That has cleared the stage for China’s massive commercial banks, such as ICBC or Bank of China. Owned by the government, but keen to make a profit, they were responsible for about 60% of all lending by China’s state-owned creditors from 2019 to 2023 (see chart 2). In high-income countries, perhaps their more natural habitat, they accounted for more than 80% of such lending.

Many of these loans look harmless enough. Lenders such as ICBC or Bank of China have followed their clients abroad, setting up subsidiaries in the world’s richest markets. They also chip in to syndicated loans alongside other global banks. In 2012 Bank of China joined JPMorgan Chase and others in making the first of several syndicated loans to Disney.

Sometimes they are just “banks doing what banks do”, says Mr Parks. Other lending, however, raises more eyebrows. A growing share of credit for acquisitions is directed towards 17 industries that governments tend to deem “sensitive”, such as telecoms infrastructure, microprocessors and companies that collect personal data. In 2015, for example, four Chinese state-owned commercial banks provided a loan to Fosun, a Chinese multinational, to help it buy Ironshore, which sold liability insurance through its American subsidiary to officials at the CIA and FBI.

How do AidData’s figures compare with other estimates of Chinese lending? According to China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the stock of loans at the end of 2023 was $805bn, plus another $644bn in trade finance. But these official figures are not directly comparable with the AidData numbers. They exclude credit extended by the overseas subsidiaries of Chinese banks and leave out loans that finance foreign direct investment, which is recorded separately. The official figures also represent the stock of loans that remained outstanding at the end of 2023, whereas AidData have added up the flow of credit over the preceding 24 years.

Mr Parks and his team may also have identified loans that even China’s authorities struggle to track. Their database spans over 1,100 lenders and donors. Although they are all owned by the Chinese state, its ministries do not have “full visibility on what all these different banks are doing”, he explains. He and his team have, on more than one occasion, discovered that Chinese officials sometimes use the AidData figures in their own work. “Having a one-stop shop where they can get all this information is too convenient to pass up,” Mr Parks reckons. Not even the Chinese government always knows exactly how generous it has been. ■

United States | Transparency in government

Release the Epstein files!

What Congress has actually voted to make public

Photograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|WASHINGTON, DC|2 min read

Listen to this story

It is the scandal that will never die. For more than six years the case of Jeffrey Epstein, a dead sex offender with links to the president and other prominent figures, has spawned a dizzying array of conspiracy theories. On November 18th American lawmakers passed a law compelling the government to release its files on Epstein. The bill has been signed by the president. Yet what exactly are the Epstein files, and what can the public expect to see?

The largest batch is held by the Department of Justice (DoJ) and encompasses two criminal investigations that unfolded between 2006 and 2019. The first involved charges that Epstein abused dozens of underage girls in Florida. That case led to a controversial plea deal in 2008. Other DoJ files accumulated during a second investigation that did result in a trafficking charge in July 2019. The department also holds information about Epstein’s apparent suicide the following month while in federal custody.

Federal agents amassed documents from property seizures as well as detailed witness interviews. A July memo from the DoJ noted that it had some 300 gigabytes of data and physical evidence, which included a large volume of images and videos of Epstein’s victims. The files also contain reams of internal DoJ communications.

Yet the narrow focus of the criminal investigations may disappoint those expecting damning new revelations about Epstein’s associates. “What’s crucial [in these cases] is what happened to the women, and not what people happen to be connected to Epstein,” says Jeremy Paul, a law professor at Northeastern University.

If the DoJ files are released, information about Epstein’s victims is likely to be extensively redacted. The DoJ can also withhold any documents that could jeopardise ongoing investigations. (Mr Trump recently ordered the department to investigate prominent Democrats associated with Epstein.) For those podcasters and politicians who believe withholding documents is evidence of conspiracy, there will be plenty to talk about. ■

United States | Learning like the ancients

AI is accelerating a tech backlash in American classrooms

Handwritten and oral exams are making a comeback

The latest in edtechPhotograph: Getty Images

Nov 20th 2025|NEW YORK|5 min read

Listen to this story

Acentury and a half before Apple marketed iPads to schools, in 1857, a Greek-born Harvard professor, Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, held a bonfire of newly introduced “blue books”, bound exam booklets for pen-and-paper tests that (to his ire) were to replace oral recitations. He lost. These booklets would torment generations of American students before yielding in turn to computerised testing. But now the blue book is making a comeback, with booklet sales more than doubling from 2022 to 2024 (see chart), according to Circana, a data firm. And oral exams appear ripe for revival, too.

From high school to university, teachers are playing defence against classroom tech that enables cheating and foments distraction. Laura Lomas, a literature professor at Rutgers University, now requires students to attend a play whose ending changes every night, so she knows if they were there. She assigns oral presentations rather than more AI-friendly PowerPoints, and allows no bathroom breaks during blue-book exams so students can’t peek at their phones. Sara Brock, a high-school English teacher in Port Washington, New York, requires students to write exercises by hand in class. Justin Reich, director of the MIT Teaching Systems Lab, says his daughter’s middle school has “more or less given up on [assigning] homework other than math.” Students are told to read instead.

Chart: The Economist

Such retrenchments are likely to keep spreading. In a 2023 survey by Intelligent, a research outfit, 66% of high-school and college instructors said they were changing assignments because of ChatGPT; of those changing, 76% required or planned to require handwritten work. And 87% said they require or plan to add an oral presentation component. A survey the same year by EdWeek Research Centre found that 43% of educators think students should solve maths problems in class using pencil and paper to show they are not using AI. And in a Stanford University pilot programme, proctors—how quaint!—prowl classrooms to monitor test-taking.

The battle for and against classroom tech in America is raging in other rich countries, notes Isabel Dans Álvarez de Sotomayor, an education scholar at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. As poorer countries race to digitise, richer countries are restricting classroom tech even as they invest in more digital infrastructure. After initially going all-in on technology, in 2023 Sweden banned digital tools for young children and now emphasises physical textbooks, handwriting and reading. Schools in Denmark and Finland are on the same page.

The reason is not just ChatGPT and the mass cheating it makes possible. Teachers are worried about mass distraction as well. In 2025 56% of educators said laptops, tablets or desktops are a major source of diverted attention, according to another EdWeek Research Centre survey. At Bowdoin College, a private liberal-arts college in Maine, the dean says that “many faculty had already marked their classrooms as, for the most part, device-free spaces” even before “the recent ubiquity of AI”.

Cheating is nothing new—in a study ten years ago, 87% of high-school students admitted to cheating at least once the month before, and the researchers found that percentage has actually come down since—but the “magnitude of cheating is substantially different” since advanced AI arrived, says Mr Reich of MIT. “We have a zillion interviews with kids of all kinds who say things like, ‘In my senior year [of high school] I never did homework. Every assignment I did used generative AI.’” The college level is no better, says Ms Lomas. “One student even quoted a paper by me that AI made up out of thin air”.

Rigorous studies have shown that classroom tech can help pupils learn algebra, but evidence of improved outcomes in other areas is thin. By contrast, the benefits handwriting offers for cognition are gaining new respect, even beyond the humanities. A computer science teacher at Hunter College High School in New York recently reinstituted handwriting for coding assignments because it helps with retention as well as critical thinking.

But not everyone who wants to go old-school can. Parents often can’t easily opt out of edtech. And Derek Vaillant, a history professor at the University of Michigan, says that while there is a consensus that teachers need to “get back to basics” by prioritising original, in-person, pen-and-paper exams, large public universities are not providing resources commensurate with the challenge by hiring enough teaching assistants. Administrators are “speaking out of both sides of their mouths”.