공부는 교과서가 최고다.

근육 생리, 수축기전에 대한 분자생물학 깊이까지 들어간 교과서

공재철 원장이 올린 자료

Movement is a fundamental characteristic of all living organisms, from bacteria to humans. Even plants and other seemingly immobile organisms move cellular components from place to place. Across the entire spectrum of life, the molecular mechanisms of movement are very similar, involving motor proteins such as myosin and dynein. But in

animals, movement has developed to the highest degree, with the evolution of muscle cells specialized for this function.

A muscle cell is essentially a device for converting the chemical energy of ATP into the mechanical energy of movement.

The three types of muscular tissue—skeletal, cardiac, and smooth—were described and compared in chapter 5. Cardiac and smooth muscle are further described in this chapter, and cardiac muscle is discussed most extensively in chapter 19. Most of the present chapter, however, concerns skeletal muscle, the type that holds the body erect against the pull of gravity and produces its outwardly visible movements.

This chapter treats the structure, contraction, and metabolism of skeletal muscle at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels of organization. Understanding muscle at these levels provides an indispensable basis for understanding such aspects of motor performance as warm-up, quickness, strength, endurance, and fatigue.

이 챕터에서는 분자생물학, 세포학, 조직학 수준의 근육의 구조, 수축, 대사에 관한 탐구.

근육에 대한 이러한 탐구는 움직임을 위한 웜업, 민첩성, 근력, 지구력, 근피로 등 측면의 이해에서 필수적인 기초임.

Such factors have obvious relevance to athletic performance, and they become very important when a lack of physical conditioning, old age, or injury interferes with a person’s ability to carry out everyday tasks or meet the extra demands for speed or strength that we all occasionally encounter.

Universal Characteristics of Muscle

The functions of the muscular system were detailed in the preceding chapter: movement, stability, communication,

control of body openings and passages, and heat production. To carry out those functions, all muscle cells have

the following characteristics:

• Responsiveness (excitability). Responsiveness is a property of all living cells, but muscle and nerve cells have developed this property to the highest degree. When stimulated by chemical signals (neurotransmitters), stretch, and other stimuli, muscle cells respond with electrical changes across the plasma membrane.

흥분성 : 근육은 신경전달물질, 스트레치, 다른 자극 등에 의해 자극을 받을때, 세포막(plasma membrane)를 따라 전기 반응이 일어남.

• Conductivity. Stimulation of a muscle fiber produces more than a local effect. The local electrical change triggers a wave of excitation that travels rapidly along the fiber and initiates processes leading to muscle contraction.

전도성 : 근섬유 자극은 국소적인 효과보다 멀리 생성됨. 국소적인 전기변화는 근섬유를 따라 빠르게 이동하고 흥분파가 전달되어 초기 자극을 따라서 근수축이 일어남.

• Contractility. Muscle fibers are unique in their ability to shorten substantially when stimulated. This enables them to pull on bones and other tissues and create movements of the body and its parts.

수축성 : 근섬유는 자극을 받을때 유일하게 짧아지는 반응이 일어남. 이러한 능력은 뼈를 당기고 다른 조직을 움직이게 함.

• Extensibility. In order to contract, a muscle cell must also be extensible—able to stretch again between contractions. Most cells rupture if they are stretched even a little, but skeletal muscle fibers can stretch to as much as three times their contracted length.

신장성 : 근육이 수축하기 위하여 근육세포는 반드시 늘어나야 함. 수축과 함께 다시 늘어나는 능력이 있음. 근육이외의 다른 조직은 늘어나면 파열이 일어남. 하지만 골격근섬유는 수축길이보다 3배나 늘어날 수 있음.

• Elasticity. When a muscle cell is stretched and then the tension is released, it recoils to its original resting length. Elasticity, commonly misunderstood as the ability to stretch, refers to this tendency of a muscle cell (or other structures) to return to the original length when tension is released.

탄성 : 근육세포가 스트레치될때 장력은 이완되고, 원래 길이로 되돌아가는 능력이 있음. 탄성도는 늘어나는 능력으로 잘못 이해되는데, 근세포의 탄성도 경향은 원래 길이로 되돌아가는 것을 말함.

Skeletal Muscle

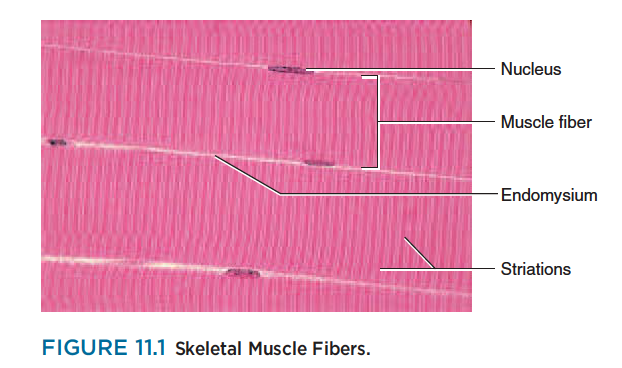

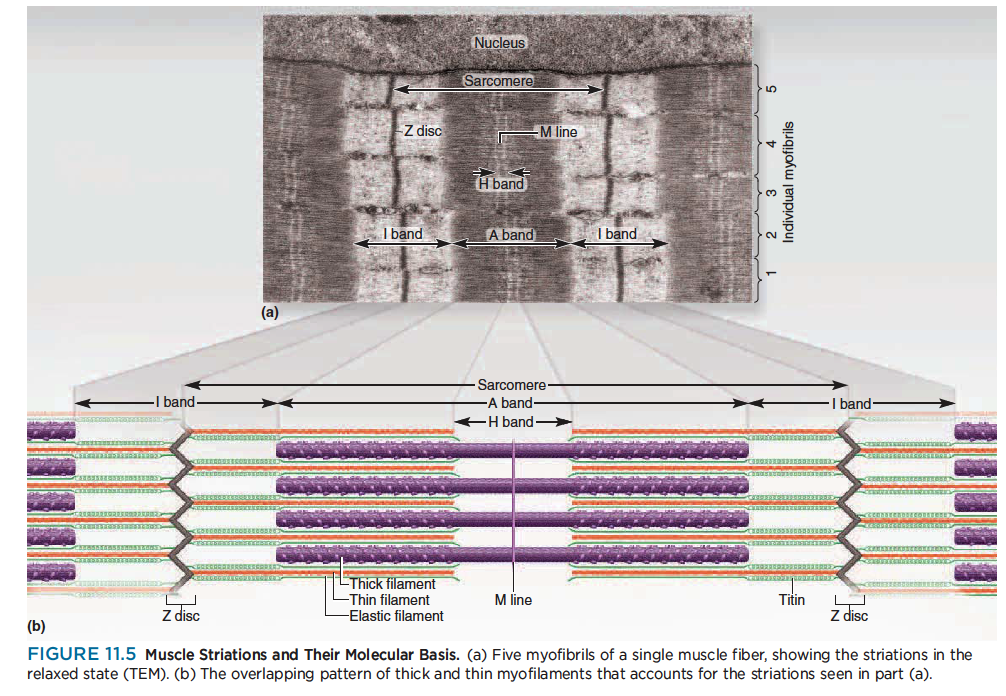

Skeletal muscle may be defined as voluntary striated muscle that is usually attached to one or more bones. A skeletal muscle exhibits alternating light and dark transverse bands, or striations (fig. 11.1), that result from an overlapping arrangement of their internal contractile proteins.

Skeletal muscle is called voluntary because it is usually subject to conscious control. The other types of

muscle are involuntary (not usually under conscious control), and they are never attached to bones.

A typical skeletal muscle cell is about 100 um in diameter and 3 cm (30,000 um) long; some are as thick

as 500 um and as long as 30 cm.

Because of their extraordinary length, skeletal muscle cells are usually called muscle fibers or myofibers.

Recall from chapter 10 that a skeletal muscle is composed not only of muscular tissue, but also of fibrous

connective tissue: the endomysium that surrounds each muscle fiber, the perimysium that bundles muscle fibers together into fascicles, and the epimysium that encloses the entire muscle (see fig. 10.1, p. 321).

These connective tissues are continuous with the collagen fibers of tendons and those, in turn, with the collagen of the bone matrix. Thus, when a muscle fiber contracts, it pulls on these collagen fibers and usually moves a bone. Collagen is neither excitable nor contractile, but it is somewhat extensible and elastic. When a muscle lengthens, for example during extension of a joint, its collagenous components resist excessive stretching and protect the muscle from injury.

콜라겐은 흥분성도 없고, 수축성도 없지만 다소 늘어나기도 하고 탄성을 가짐.

근육이 늘어날 때(관절이 신장될 때), 콜라겐성분은 과도한 스트레칭을 방지하고, 손상으로부터 근육을 보호함.

When a muscle relaxes, elastic recoil of the collagen may help to return the muscle to its resting length and keep it from becoming too flaccid. Some authorities contend that recoil of the tendons and other collagenous tissues contribute significantly to the power output and efficiency of a muscle. When you are

running, for example, recoil of the calcaneal tendon may help to lift the heel and produce some of the thrust

as your toes push off from the ground. (Such recoil contributes significantly to the long, energy-efficient

leaping of kangaroos.) Others feel that the elasticity of these components is negligible in humans and that the recoil is produced entirely by components within the muscle fibers.

근육이 이완될 때, 콜라겐의 탄성 움츠러듬(elastic recoil)은 근육이 정상길이로 돌아오는 것을 돕고, 충분히 이완됨으로부터 그것을 유지함.

The Muscle Fiber

In order to understand muscle function, you must know how the organelles and macromolecules of a muscle fiber are arranged. Perhaps more than any other cell, a muscle fiber exemplifies the adage, Form follows function. It has a complex, tightly organized internal structure in which even the spatial arrangement of protein molecules is closely tied to its contractile function.

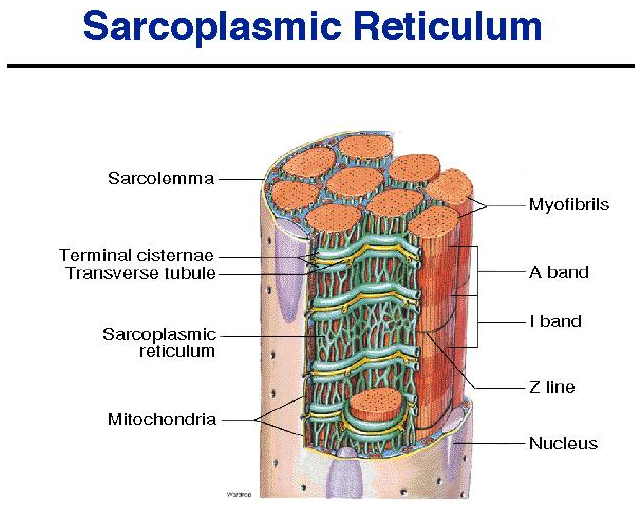

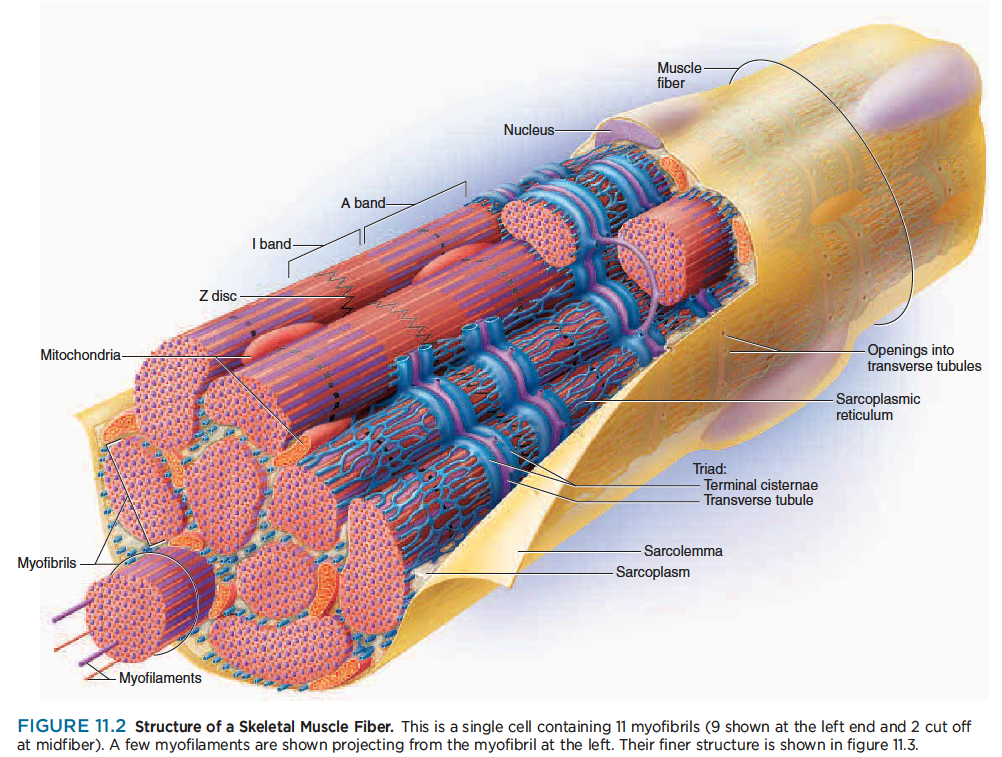

The plasma membrane of a muscle fiber is called the sarcolemma,1 and its cytoplasm is called the sarcoplasm.

The sarcoplasm is occupied mainly by long protein bundles called myofibrils about 1 m in diameter (fig. 11.2)—not to be confused with myofibers, the muscle cells themselves. It also contains an abundance of glycogen, a starchlike carbohydrate that provides energy for the cell during heightened levels of exercise, and the red pigment myoglobin, which stores oxygen until needed for muscular activity.

Muscle fibers have multiple flattened or sausage shaped nuclei pressed against the inside of the sarcolemma. Their unusual multinuclear condition results from their embryonic development—several stem cells called myoblasts2 fuse to produce each muscle fiber, with each myoblast contributing a nucleus to the mature fiber.

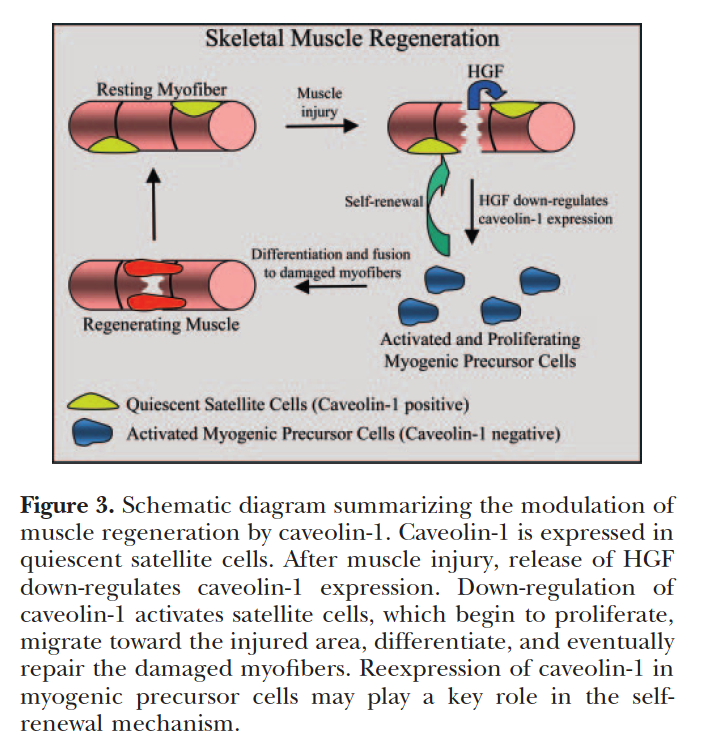

Some myoblasts remain as unspecialized satellite cells between the muscle fiber and endomysium. When a muscle is injured, satellite cells can multiply and produce new muscle fibers to some degree. Most muscle repair, however, is by fibrosis rather than by regeneration of functional muscle.

어떤 근아세포(myoblast)는 근섬유와 근내막 사이에 위성세포(satellite cell)가 있음. 근육이 손상될때, 위성세포는 세로운 근섬유를 생성할 수 있음. 대부분의 근육은 기능적인 근육의 재생에 의한 것보다는 섬유화에 의해서 회복됨.

Most other organelles of the cell, such as mitochondria, are packed into the spaces between the myofibrils.

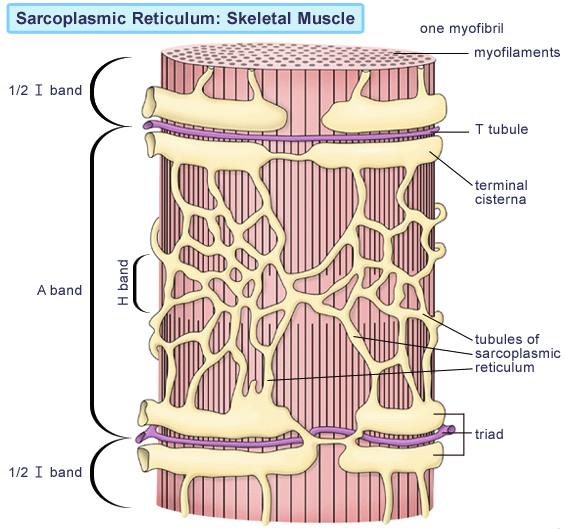

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum, here called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), forms a network around

each myofibril. It periodically exhibits dilated end-sacs called terminal cisternae, which cross the muscle fiber from one side to the other.

근소포체는 근원섬유 주위의 네트워크를 이룸.

The sarcolemma has tubular infoldings called transverse (T) tubules, which penetrate through the cell and emerge on the other side. Each T tubule is closely associated with two terminal cistern, running alongside it on each side. A T tubule and the two terminal cisternae associated with it constitute a triad.

근초(sarcolemma)는 T 튜불을 가지고 .. 근소포체 말단조를 이룸.

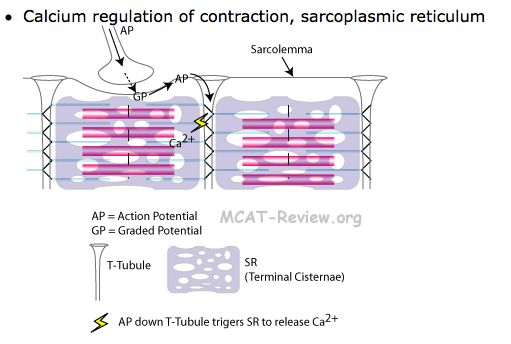

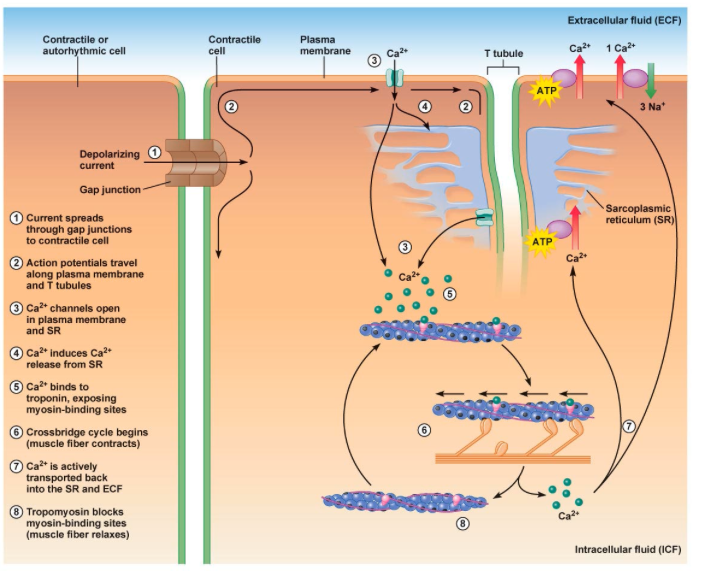

The SR is a reservoir of calcium ions; it has gated channels in its membrane that open at the right times to release a flood of Ca2 into the cytosol, where the calcium activates the muscle contraction process. The T tubule signals the SR when to release these calcium bursts.

근소포체는 칼슘이온의 저장고이고, gated channel을 가지고 cytosol안으로 칼슘 분비가 필요한 적절한 시간에 열림.

칼슘은 근수축과정을 활성화함.

근수축 과정 그림

Myofilaments

Let’s return to the myofibrils just mentioned—the long protein cords that fill most of the muscle cell—and look at their structure at a finer, molecular level. It is here that the key to muscle contraction lies. Each myofibril is a bundle of parallel protein microfilaments called myofilaments (see the left end of figure 11.2).

There are three kinds of myofilaments:

마이오신, 액틴, 티틴

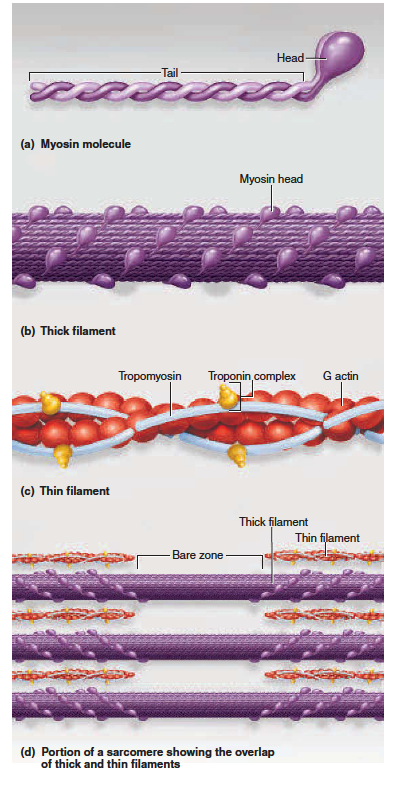

1. Thick filaments (fig. 11.3a, b, d) are about 15 nm in diameter. Each is made of several hundred molecules of a protein called myosin. A myosin molecule is shaped like a golf club, with two chains intertwined to form a shaftlike tail and a double globular head projecting from it at an angle. A thick filament

may be likened to a bundle of 200 to 500 such “golf clubs,” with their heads directed outward in a helical

array around the bundle. The heads on one half of the thick filament angle to the left, and the heads

on the other half angle to the right; in the middle is a bare zone with no heads.

마이오신은 두꺼운 필라멘트. 마이오신 헤드는 골프 클럽과 같은 모양으로 두가닥이 꼬여 샤프트같은 꼬리를 만들고 ..

2. Thin filaments (fig. 11.3c, d), 7 nm in diameter, are composed primarily of two intertwined strands of

a protein called fibrous (F) actin. Each F actin is like a bead necklace—a string of subunits called globular

(G) actin. Each G actin has an active site that can bind to the head of a myosin molecule. A thin filament

also has 40 to 60 molecules of yet another protein called tropomyosin. When a muscle fiber is relaxed,

tropomyosin blocks the active sites of six or seven G actins and prevents myosin from binding to them.

Each tropomyosin molecule, in turn, has a smaller calcium-binding protein called troponin bound to it.

3. Elastic filaments (see fig. 11.5b), 1 nm in diameter, are made of a huge springy protein called titin3

(connectin). They flank each thick filament and anchor it to a structure called the Z disc. This helps

to stabilize the thick filament, center it between the thin filaments, and prevent over stretching.

Myosin and actin are called contractile proteins because they do the work of shortening the muscle fiber. Tropomyosin and troponin are called regulatory proteins because they act like a switch to determine when the fiber can contract and when it cannot. Several clues as to how they do this may be apparent from what has already been said—calcium ions are released into the sarcoplasm to activate contraction; calcium binds to troponin; troponin is also bound to tropomyosin; and tropomyosin blocks the active sites of actin, so that myosin cannot bind to it when the muscle is not stimulated. Perhaps you are already forming some idea of the contraction mechanism to be explained shortly.

At least seven other accessory proteins occur in the thick and thin filaments or are associated with them.

Among other functions, they anchor the myofilaments, regulate their length, and keep them aligned with each other for optimal contractile effectiveness. The most clinically important of these is dystrophin, an enormous protein located between the sarcolemma and the outermost myofilaments. It links actin filaments to a peripheral protein on the inner face of the sarcolemma (fig. 11.4).

That protein, in turn, is linked to a complex of transmembrane proteins; they are linked to proteins external to the muscle fiber; and ultimately, these linkages lead to a collagen–glycoprotein layer, the basal lamina, and to the fibrous endomysium surrounding the entire muscle fiber. Thus, dystrophin is a key element transferring the forces of the myofilament movement to the connective tissues of the muscle as a whole. Genetic defects in dystrophin are responsible for the disabling disease, muscular dystrophy

(see Insight 11.5).

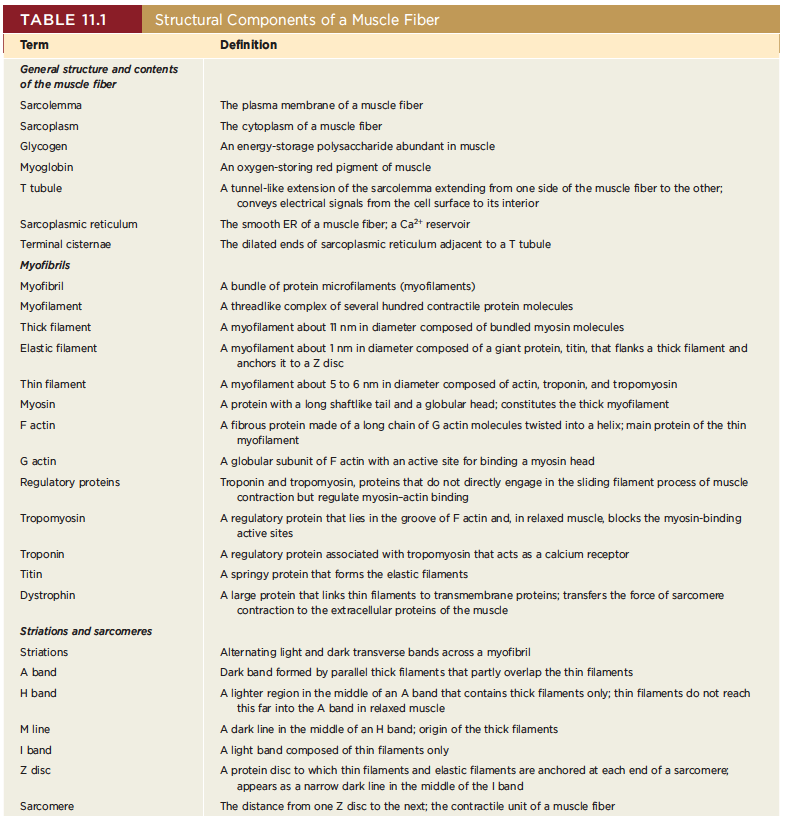

General structure and contents of the muscle fiber

Sarcolemma : The plasma membrane of a muscle fiber

Sarcoplasm : The cytoplasm of a muscle fiber

Glycogen : An energy-storage polysaccharide abundant in muscle

Myoglobin : An oxygen-storing red pigment of muscle

T tubule : A tunnel-like extension of the sarcolemma extending from one side of the muscle fiber to the other; conveys electrical signals from the cell surface to its interior

Sarcoplasmic reticulum : The smooth ER of a muscle fiber; a Ca2 reservoir

Terminal cistern : The dilated ends of sarcoplasmic reticulum adjacent to a T tubule

Myofibrils

Myofibril : A bundle of protein microfilaments (myofilaments)

Myofilament : A threadlike complex of several hundred contractile protein molecules

Thick filament : A myofilament about 11 nm in diameter composed of bundled myosin molecules

Elastic filament : A myofilament about 1 nm in diameter composed of a giant protein, titin, that flanks a thick filament and anchors it to a Z disc

Thin filament : A myofilament about 5 to 6 nm in diameter composed of actin, troponin, and tropomyosin

Myosin : A protein with a long shaftlike tail and a globular head; constitutes the thick myofilament

F actin : A fibrous protein made of a long chain of G actin molecules twisted into a helix; main protein of the thin myofilament

G actin : A globular subunit of F actin with an active site for binding a myosin head

Regulatory proteins : Troponin and tropomyosin, proteins that do not directly engage in the sliding filament process of muscle contraction but regulate myosin–actin binding

Tropomyosin : A regulatory protein that lies in the groove of F actin and, in relaxed muscle, blocks the myosin-binding active sites

Troponin : A regulatory protein associated with tropomyosin that acts as a calcium receptor

Titin : A springy protein that forms the elastic filaments

Dystrophin : A large protein that links thin filaments to transmembrane proteins; transfers the force of sarcomere contraction to the extracellular proteins of the muscle

Striations and sarcomeres

Striations : Alternating light and dark transverse bands across a myofibril

A band : Dark band formed by parallel thick filaments that partly overlap the thin filaments

H band : A lighter region in the middle of an A band that contains thick filaments only; thin filaments do not reach this far into the A band in relaxed muscle

M line: A dark line in the middle of an H band; origin of the thick filaments

I band : A light band composed of thin filaments only

Z disc : A protein disc to which thin filaments and elastic filaments are anchored at each end of a sarcomere; appears as a narrow dark line in the middle of the I band

Sarcomere : The distance from one Z disc to the next; the contractile unit of a muscle fiber

11.3 The Nerve–Muscle Relationship

Skeletal muscle never contracts unless it is stimulated by a nerve (or artificially with electrodes). If its nerve

connections are severed or poisoned, a muscle is paralyzed. If the connection is not restored, the paralyzed muscle undergoes a shrinkage called denervation atrophy. Thus, muscle contraction cannot be understood without first understanding the relationship between nerve and muscle cells.

Motor Neurons and Motor Units

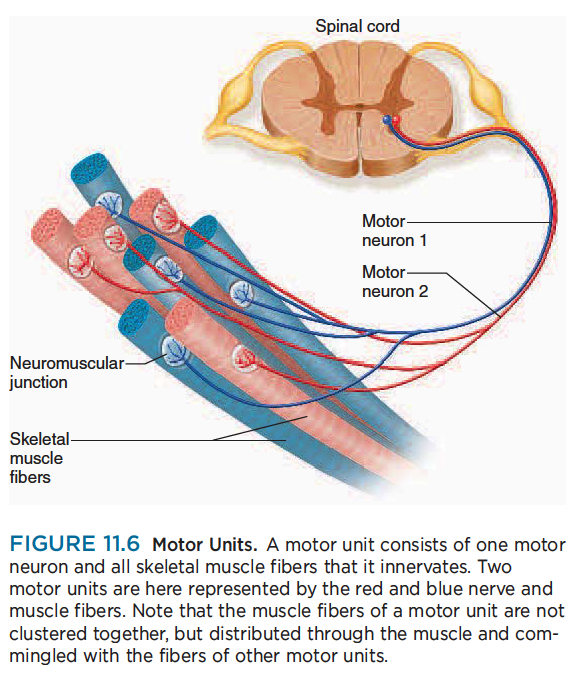

Skeletal muscles are served by nerve cells called somatic motor neurons, whose cell bodies are in the brainstem and spinal cord. Their axons, called somatic motor fibers, lead to the skeletal muscles (fig. 11.6).

골결근은 운동신경원이라고 불리는 신경세포로 이어져 있고, 운동신경원의 세포체는 뇌간이나 척수에 있음. 그들의 축삭(체성 운동신경섬유)은 골격근에 이어져 있음.

Each nerve fiber branches out to a number of muscle fibers, but each muscle fiber is supplied by only one motor neuron.

각각의 신경섬유는 많은 근섬유로 이어짐. 하지만 각각 근섬유는 하나의 운동신경원의 지배를 받음.

When a nerve signal approaches the end of an axon, it spreads out over all of its terminal branches and stimulates all the muscle fibers supplied by them. Thus, these muscle fibers contract in unison. Since they behave as a single functional unit, one nerve fiber and all the muscle fibers innervated by it are called a motor unit.

신경신호가 축삭의 끝에 도달할때, 신경말단가지에 퍼지고 근육이 수축함. 하나의 신경섬유는 운동단위라고 불리는 신경섬유가 근섬유를 신경지배함.

The muscle fibers of a single motor unit are not clustered together but are dispersed throughout a muscle. Thus, when they are stimulated, they cause a weak contraction over a wide area—not just a localized twitch in one small region. An effective muscle contraction usually requires the activation of several motor units at once.

단일 운동단위의 근섬유는 서로 무리지어있지 않지만 근육을 통해서 퍼짐. 그래서 신경이 자극될때, 그것은 넓은 지역에 근수축을 일으킴. 효과적인 근수축은 일반적으로 한번에 몇개의 운동단위 활성화가 필요함.

On average, about 200 muscle fibers are innervated by each motor neuron, but motor units can be much smaller or larger than this to serve different purposes. Where fine control is needed, we have small motor units. In the muscles of eye movement, for example, each neuron controls only 3 to 6 muscle fibers. Where strength is more important than fine control, we have large motor units. In the gastrocnemius muscle of the calf, for example, one motor neuron may control up to 1,000 muscle fibers.

평균적으로 보면 각각의 운동신경원에 의해서 대략 200개 근섬유가 지배받고 있음. 하지만 운동단위는 목적에 따라 많기도 하고, 적기도 함. 세밀한 움직임을 필요로 하는 근육은 적은 운동단위를 가짐. 예를들어 눈움직임 근육은 각각 운동신경원에 오직 3~6개의 운동단위를 가지고 있음. 반면 큰힘이 필요한 종아리 근육은 많은 운동단위를 가짐. 비복근은 하나의 운동신경원에 1000개가 넘는 근섬유가 지배하고 있음.

Another way to look at this is that 1,000 muscle fibers may be innervated by 200 neurons in a muscle with small motor units, but by only 1 or 2 neurons in a muscle with large motor units. Consequently, small motor units provide a relatively fine degree of control. Turning a few motor neurons on or off produces a small, subtle change in the action of such a muscle.

다른 시각으로 보면 1000개의 근섬유는 작은 운동단위 근육에서는 200개 운동신경원에 의해서 신경지배되지만, 큰 운동단위를 가진 근육은 오직 1개 또는 2개 운동신경원에 의해서 신경지배됨. 결과적으로 작은 운동단위는 상대적으로 세밀한 움직임을 제공함. ...

Large motor units generate more strength but less subtlety of action. Activating just a few motor neurons produces a very large change in a muscle with large motor units. Fine movements of the eye and hand thus depend on small motor units, while powerful movements of the gluteal or quadriceps muscles

depend on large motor units. In addition to adjustments in strength and control, another advantage of having multiple motor units in a muscle is that they are able to work in shifts.

큰 운동단위는 큰 힘을 생성함. 몇개의 운동신경원을 활성화하면 큰 운동단위 근육은 매우 큰 힘을 만들어냄. 눈이나 손과 같은 작은 움직임은 작은 운동단위에 의존하고, 큰 근육인 대퇴사두근, 엉덩이 근육은 큰 운동단위에 의존함.

근력과 조절에서 복합 운동단위를 가지는 이점은 움직임 변이를 일으킬 수 있음.

Muscle fibers fatigue when subjected to continual stimulation. If all of the fibers in one of your postural muscles fatigued at once, for example, you might collapse. To prevent this, other motor units take over while the fatigued ones recover, and the muscle as a whole can sustain long-term contraction. The role of motor units in muscular strength is further discussed later in the chapter.

지속적인 자극이 주어지면 근섬유 피로가 발생함. 만약 자세유지근의 하나가 피로에 빠지면 넘어질 것임. 이것을 방지하기 위해서 다른 운동단위가 서로 교대함.

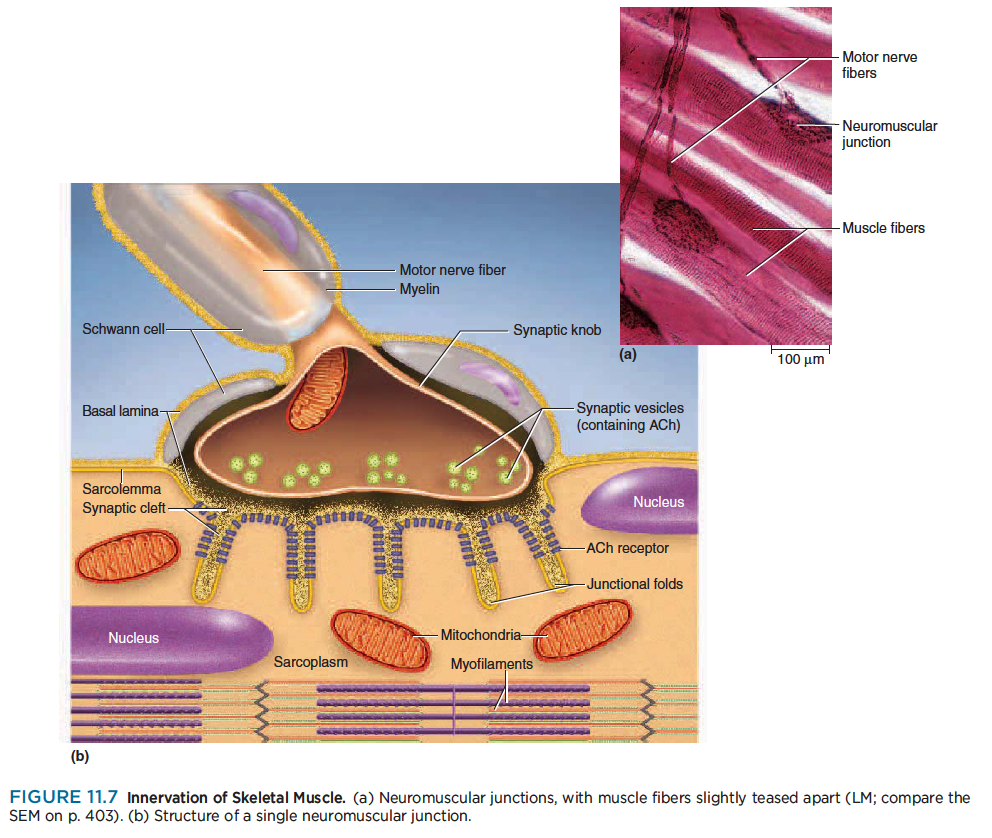

The Neuromuscular Junction

The point where a nerve fiber meets its target cell is called a synapse (SIN-aps). When the target cell is a muscle fiber, the synapse is called a neuromuscular junction (NMJ), or motor end plate (fig. 11.7).

신경근 접합부위(운동종판)

Each terminal branch of the nerve fiber within the NMJ forms a separate synapse with the muscle fiber. The sarcolemma of the NMJ is irregularly indented, a little like a handprint pressed into soft clay. If you imagine the nerve fiber to be like your forearm and your hand to be spread out on the handprint, the individual synapses would be like the points where your fingertips contact the clay. Thus, one nerve

fiber stimulates the muscle fiber at several points within the NMJ.

At each synapse, the nerve fiber ends in a bulbous swelling called a synaptic knob. The knob doesn’t directly touch the muscle fiber but is separated from it by a narrow space called the synaptic cleft, about 60 to 100 nm wide (scarcely any wider than the thickness of one plasma membrane). A third cell, called a Schwann cell, envelops the entire junction and isolates it from the surrounding tissue fluid.

The synaptic knob contains spheroidal organelles called synaptic vesicles, which are filled with a chemical

called acetylcholine (ACh) (ASS-eh-tul-CO-leen)—one of many neurotransmitters to be introduced in chapter 12.

The electrical signal (nerve impulse) traveling down a nerve fiber cannot cross the synaptic cleft like a spark jumping between two electrodes—rather, it causes the synaptic vesicles to undergo exocytosis, releasing ACh into the cleft. ACh thus functions as a chemical messenger from the nerve cell to the muscle cell.

To respond to this chemical, the muscle fiber has about 50 million ACh receptors—proteins incorporated

into its plasma membrane. Nearly all of these occur directly across from the synaptic knobs; very few are

found anywhere else on the muscle fiber. To maximize the number of ACh receptors and thus its sensitivity to the neurotransmitter, the sarcolemma in this area has numerous infoldings, about 1 μm deep, called junctional folds, which increase the surface area of ACh-sensitive membrane.

The muscle nuclei beneath the folds are specifically dedicated to the synthesis of ACh receptors and

other proteins of the local sarcolemma. A deficiency of ACh receptors leads to muscle paralysis in the disease myasthenia gravis (see Insight 11.5, p. 435).

The entire muscle fiber and the Schwann cell of the NMJ are surrounded by a basal lamina, which separates them from the surrounding connective tissue. Composed partially of collagen and glycoproteins, the basal lamina passes through the synaptic cleft and virtually fills it.

Both the sarcolemma and that part of the basal lamina in the cleft contain an enzyme called acetylcholinesterase (AChE) (ASS-eh-till-CO-lin-ESS-ter-ase). This enzyme breaks down ACh after the ACh has stimulated the muscle cell; thus, it is important in turning off muscle contraction and allowing the muscle to relax (see Insight 11.1).

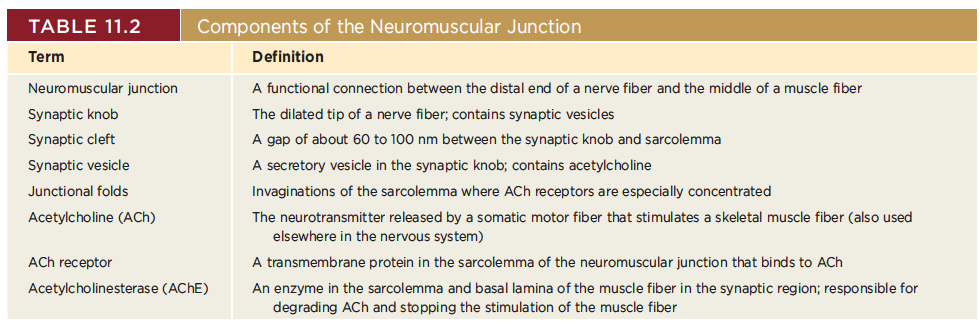

You must be very familiar with the foregoing terms to understand how a nerve stimulates a muscle fiber and how the fiber contracts. They are summarized in table 11.2 for your later reference.

Electrically Excitable Cells

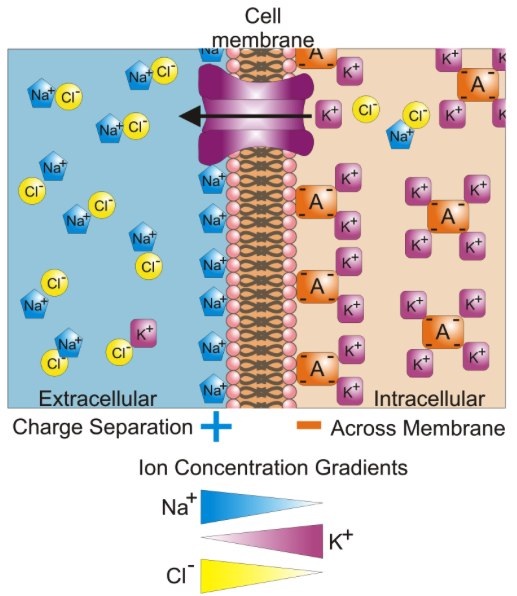

Muscle fibers and neurons are regarded as electrically excitable cells because their plasma membranes exhibit voltage changes in response to stimulation. The study of the electrical activity of cells, called electrophysiology, is a key to understanding nervous activity, muscle contraction, the heartbeat, and other physiological phenomena. The details of electrophysiology are presented in chapter 12, but a few fundamental principles must be introduced here so you can understand muscle excitation. In an unstimulated (resting) cell, there are more anions (negative ions) on the inside of the plasma membrane

than on the outside.

Thus, the plasma membrane is electrically polarized, or charged, like a little battery. In a resting muscle cell, there is an excess of sodium ions (Na) in the extracellular fluid (ECF) outside the cell and an excess of potassium ions (K) in the intracellular fluid (ICF) within the cell. Also in the ICF, and unable to penetrate

the plasma membrane, are anions such as proteins, nucleic acids, and phosphates. These anions make the inside of the plasma membrane negatively charged by comparison to its outer surface.

A difference in electrical charge from one point to another is called an electrical potential, or voltage. The

difference is typically 12 volts (V) for a car battery and 1.5 V for a flashlight battery, for example. On the sarcolemma of a muscle cell, the voltage is much smaller, about –90 millivolts (mV), but critically important to life. (The negative sign refers to the relatively negative charge on the intracellular side of the membrane.)

This voltage is called the resting membrane potential (RMP). It is maintained by the sodium–potassium pump, as noted in chapter 3.

When a nerve or muscle cell is stimulated, dramatic things happen electrically, as we shall soon see in the

excitation of muscle. Ion gates in the plasma membrane open and Na instantly diffuses down its concentration gradient into the cell. These cations override the negative charges in the ICF, so the inside of the plasma membrane briefly becomes positive. This change is called depolarization of the membrane.

Immediately, Na gates close and K gates open. K rushes out of the cell, partly because it is repelled by the positive sodium charge and partly because it is more concentrated in the ICF than in the ECF, so it diffuses down its concentration gradient when it has the opportunity. The loss of positive potassium ions from the cell turns the inside of the membrane negative again (repolarization).

This quick up-and-down voltage shift, from the negative RMP to a positive value and then back to a negative value again, is called an action potential. The RMP is a stable voltage seen in a “waiting” cell, whereas the action potential is a quickly fluctuating voltage seen in an active, stimulated cell.

Chapter 12 explains the RMP and the mechanism of action potentials more fully. Action potentials have a way of perpetuating themselves—an action potential at one point on a plasma membrane causes another one to happen immediately in front of it, which triggers another one a little farther along, and so forth. A wave of action potentials spreading along a nerve fiber like this is called a nerve impulse or nerve signal. Such signals also travel along the sarcolemma of a muscle fiber. We will see how this leads to muscle contraction.