신경과학은 알아두면 정말 유용할때가 많다.

인체가 느끼는 모든 감각의 상행로에 대한 탐구

의학을 하는 사람에게는 필수적 지식이다.

panic bird...

![]() Ascending Sensory Pathways.pdf

Ascending Sensory Pathways.pdf

A variety of sensory receptors scattered throughout the body can become activated by exteroceptive, interoceptive, or proprioceptive input. Exteroceptive input relays sensory information about the body’s interaction with the external environment. Interoceptive input relays information about the body’s internal state, whereas proprioceptive input conveys information about position sense from the body and its component parts.

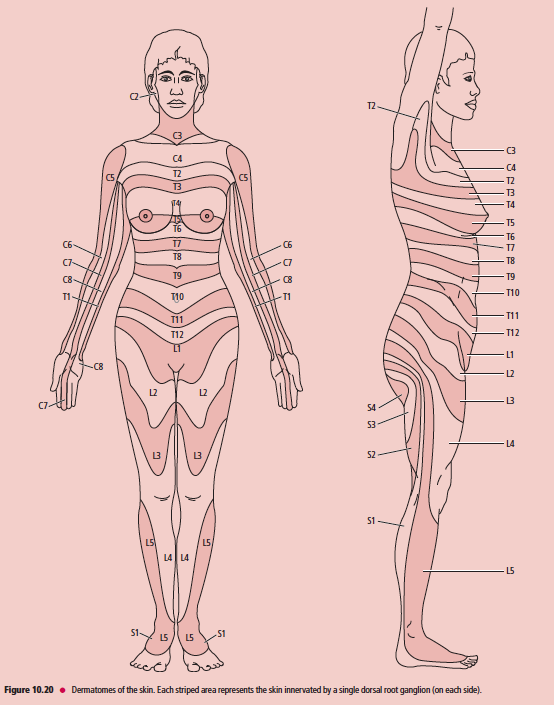

Each receptor is specialized to detect mechanical, chemical, nociceptive (L. nocere, “to injure,” “painful”), or thermal stimuli. Activation of a sensory receptor is converted into nerve impulses and this sensory input is then conveyed via the fibers of the cranial or spinal nerves to their respective relay nuclei in the central nervous system (CNS). The sensory information is then further processed as it progresses, via the ascending sensory systems (pathways), to the cerebral cortex or to the cerebellum. Sensory information is also relayed to other parts of the CNS where it may function to elicit a reflex response, or may be integrated into pattern-generating circuitry.

The ascending sensory pathways are classified according to the functional components (modalities) they carry as well as by their anatomical localization. The two functional categories are the general somatic afferent (GSA) system, which transmits sensory information such as touch, pressure, vibration, pain, temperature, stretch, and position sense from somatic structures; and the general visceral afferent (GVA) system,which transmits sensory information such as pressure, pain, and other visceral sensation from visceral structures.

- 일반체성구심감각 시스템은 촉각, 압각, 진동각, 통증, 온도, 늘어남, 위치감각 을 전달함.

- 일반내장구심감각 시스템은 압각, 통증 그리고 다른 내장감각을 전달함.

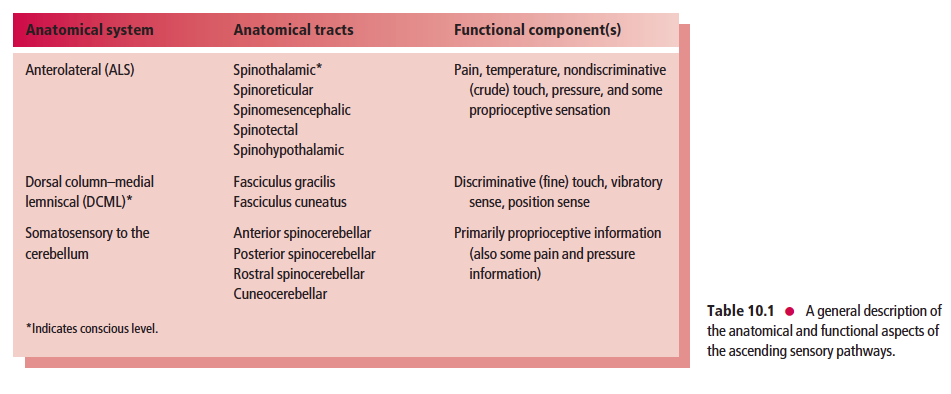

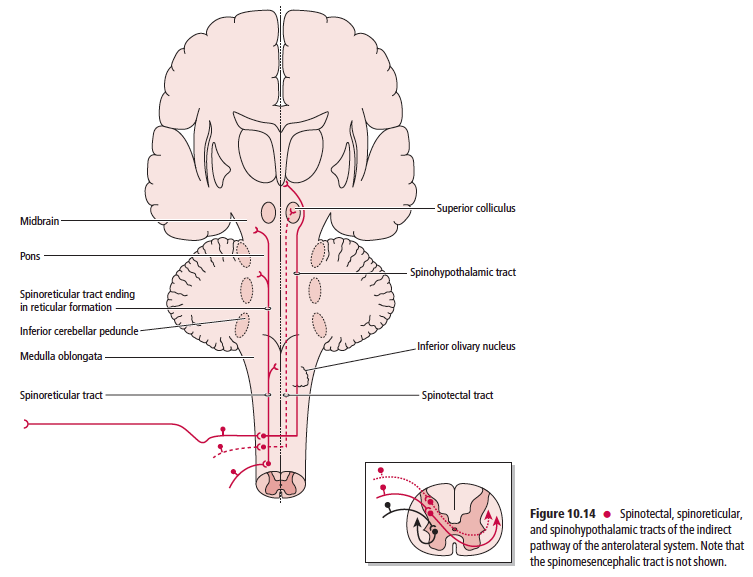

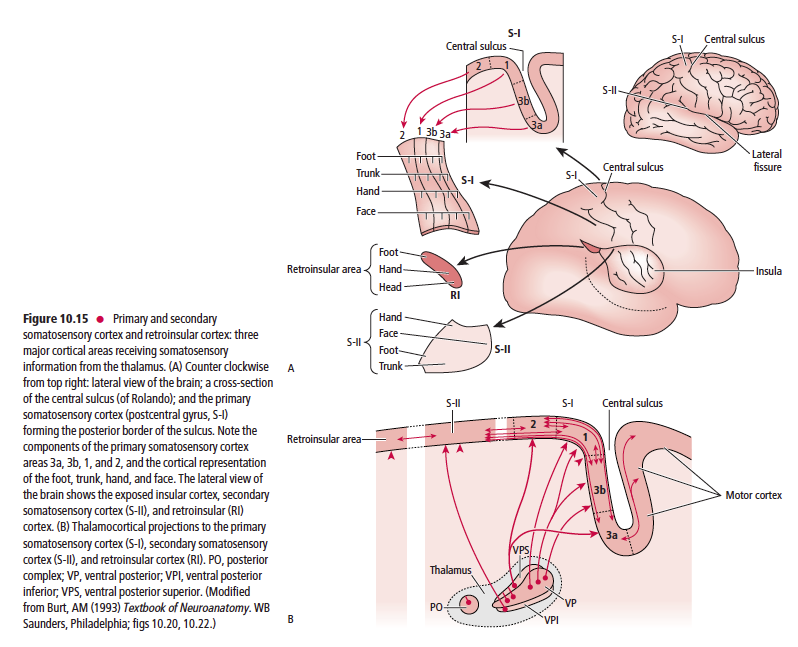

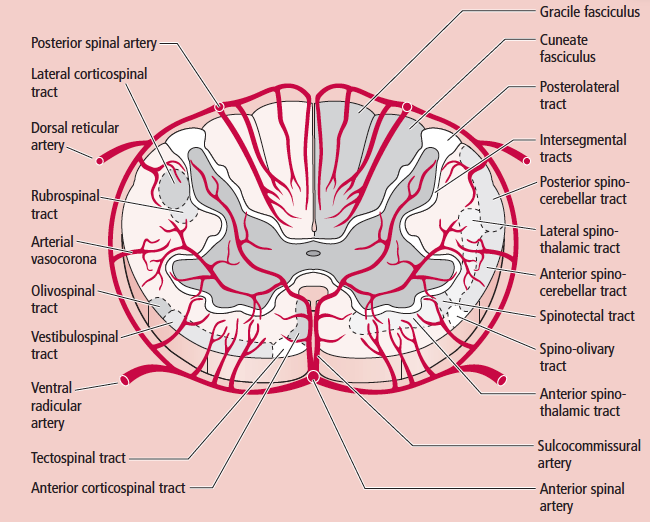

Anatomically, the ascending sensory systems consist of three distinct pathways: the anterolateral system (ALS), the dorsal column–medial lemniscal (DCML) pathway, and the somatosensory pathways to the cerebellum. The anterolateral system, which includes the spinothalamic, spinoreticular, spinomesencephalic, spinotectal, and spinohypothalamic tracts, relays predominantly pain and temperature sensation, as well as nondiscriminative (crude or poorly localized) touch, pressure, and some proprioceptive sensation (Table 10.1).

- 상행로는 세가지. ALS, DCML, somatosensory to the cerebellum 경로가 있음.

- ALS 경로는 spinothalmic, spinoreticular, spinomesencephalic, spinotectal, spinohypothalamic가 있어 통증, 온도, 촉각, 온도각, 압력, 약간의 고유수용감각을 전달함.

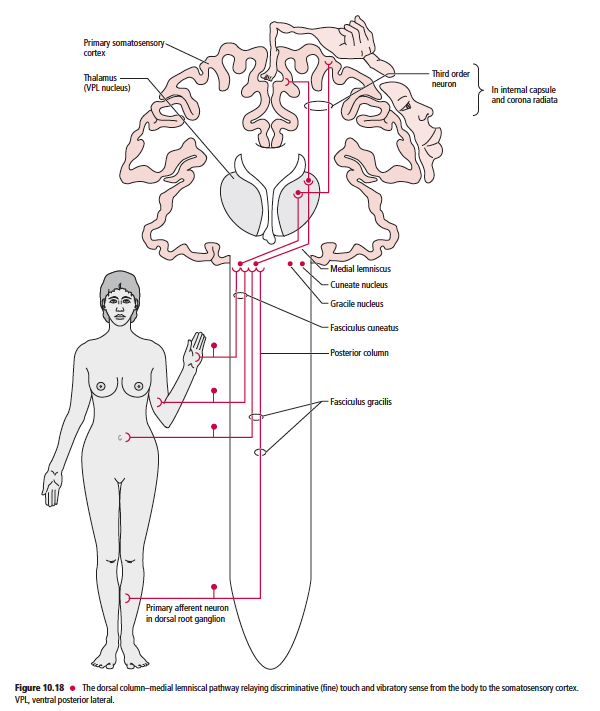

The dorsal column–medial lemniscal pathway (which includes the fasciculus gracilis, fasciculus cuneatus, and medial lemniscus) relays discriminative (fine) tactile sense, vibratory sense, and position sense (Table 10.1). The somatosensory pathways to the cerebellum, which include the anterior, posterior, and rostral spinocerebellar, as well as the cuneocerebellar tracts, relay primarily proprioceptive (but also some pain and pressure) information (Table 10.1).

- DCML경로는 fasciculus gracilis, fasciculus cuneatus가 있어서 분별감각, 진동각, 위치감각 등을 전달함.

The ascending sensory pathways are the main avenues by which information concerning the body’s interaction with the external environment, its internal condition, and the position and movement of its parts, reach the brain. One similarity shared by all three ascending sensory pathways from the body (not including the head or face) is that the first order neuron cell bodies reside in the dorsal root ganglia. It is interesting to note that conscious perception of sensory information from external stimuli is mediated by the spinothalamic and DCML pathways to the ventral posterior lateral nucleus of the thalamus, whereas sensations that do not reach consciousness are mediated by the spinoreticular, spinomesencephalic, spinotectal, spinohypothalamic, and the anterior, posterior, and rostral spinocerebellar, and cuneocerebellar tracts. These tracts terminate in the reticular formation, mesencephalon, hypothalamus and cerebellum, respectively.

Sensory input may ultimately elicit a reflex or other motor response because of the functional integration of the ascending (somatosensory) pathways, the cerebellum, and the somatosensory cortex, as well as the motor cortex and descending (motor) pathways. Furthermore, descending projections from the somatosensory cortex, as well as from the raphe nucleus magnus and the dorsolateral pontine reticular formation to the somatosensory relay nuclei of the brainstem and spinal cord, modulate the transmission of incoming sensory impulses to higher brain centers.

This chapter includes a description of the sensory receptors and the ascending sensory pathways from the body, whereas the ascending sensory pathways from the head, transmitted mostly by the trigeminal system, are described in Chapter 15.

SENSORY RECEPTORS

Although sensory receptors vary according to their morphology, the velocity of conduction, and the modality to

which they respond, as well as to their location in the body, they generally all function in a similar fashion. The stimulus to which a specific receptor responds causes an alteration in the ionic permeability of the nerve endings, generating a receptor potential that results in the formation of action

potentials. This transformation of the stimulus into an electrical

signal is referred to as sensory transduction.

Some receptors that respond quickly and maximally at

the onset of the stimulus, but stop responding even if the

stimulus continues, are known as rapidly adapting (phasic)

receptors. These are essential in responding to changes but

they ignore ongoing processes, such as when one wears a

wristwatch and ignores the continuous pressure on the skin

of the wrist. However, there are other receptors, slowly

adapting (tonic) receptors, that continue to respond as long

as the stimulus is present.

Sensory receptors are classified according to the source

of the stimulus or according to the modality to which they respond. It is important to note that, in general, receptors do

not transmit only one specific sensation.

Classification according to stimulus source

Receptors that are classified according to the source of the

stimulus are placed in one of the following three categories:

exteroceptors, proprioceptors, or interoceptors.

Exteroceptors are close to the body surface and are specialized to detect sensory information from the external environment

1 Exteroceptors are close to the body surface and are specialized

to detect sensory information from the external

environment (such as visual, olfactory, gustatory, auditory,

and tactile stimuli). Receptors in this class are sensitive

to touch (light stimulation of the skin surface),

pressure (stimulation of receptors in the deep layers of the

skin, or deeper parts of the body), temperature, pain, and

vibration. Exteroceptors are further classified as teloreceptors

or contact receptors:

• teloreceptors (G. tele, “distant”), include receptors

that respond to distant stimuli (such as light or

sound), and do not require direct physical contact

with the stimulus in order to be stimulated;

• contact receptors, which transmit tactile, pressure,

pain, or thermal stimuli, require direct contact of the

stimulus with the body.

Proprioceptors transmit sensory information from muscles, tendons, and

joints about the position of a body part, such as a limb in space

2 Proprioceptors transmit sensory information from

muscles, tendons, and joints about the position of a body

part, such as a limb in space. There is a static position

sense relating to a stationary position and a kinesthetic

sense (G. kinesis, “movement”), relating to the movement

of a body part. The receptors of the vestibular system

located in the inner ear, relaying sensory information

about the movement and orientation of the head, are also

classified as proprioceptors.

Interoceptors detect sensory information concerning the status of the body’s

internal environment

3 Interoceptors detect sensory information concerning the

status of the body’s internal environment, such as stretch,

blood pressure, pH, oxygen or carbon dioxide concentration,

and osmolarity.

Classification according to modality

Receptors are further classified into the following three

categories according to the modality to which they respond:

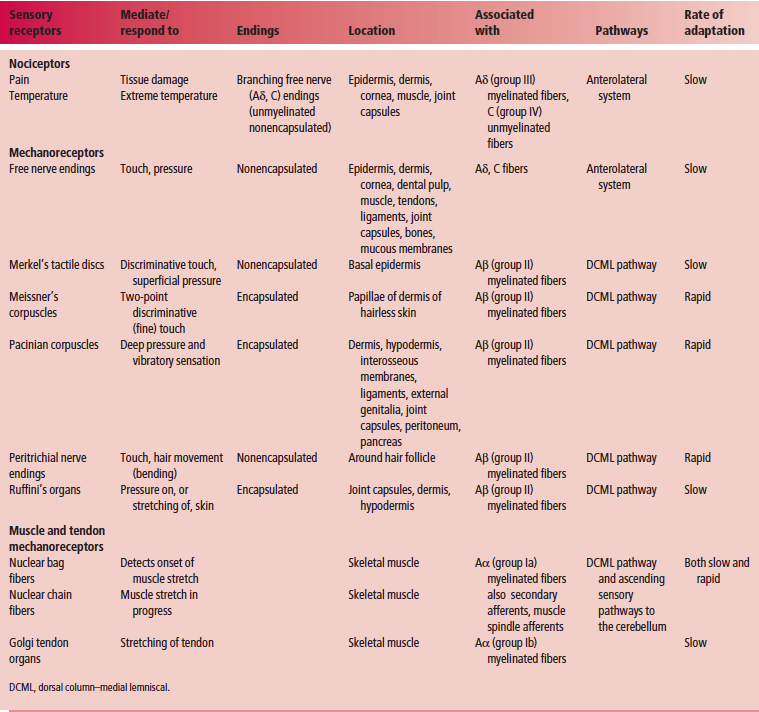

nociceptors, thermoreceptors, and mechanoreceptors(Table 10.2).

Nociceptors

Nociceptors are rapidly adapting receptors that are sensitive to noxious or

painful stimuli

Nociceptors are rapidly adapting receptors that are sensitive

to noxious or painful stimuli. They are located at the peripheral

terminations of lightly myelinated free nerve endings

of type Aδ fibers, or unmyelinated type C fibers, transmitting

pain. Nociceptors are further classified into three types.

1 Mechanosensitive nociceptors (of Aδ fibers), which are

sensitive to intense mechanical stimulation (such as

pinching with pliers) or injury to tissues.

2 Temperature-sensitive (thermosensitive) nociceptors

(of Aδ fibers), which are sensitive to intense heat and cold.

3 Polymodal nociceptors (of C fibers), which are sensitive

to noxious stimuli that are mechanical, thermal, or chemical

in nature. Although most nociceptors are sensitive

to one particular type of painful stimulus, some may

respond to two or more types.

Nociception is the reception of noxious sensory information

elicited by tissue injury, which is transmitted to the CNS

by nociceptors. Pain is the perception of discomfort or an

agonizing sensation of variable magnitude, evoked by the

stimulation of sensory nerve endings.

Thermoreceptors

Thermoreceptors are sensitive to warmth or cold

Thermoreceptors are sensitive to warmth or cold. These

slowly adapting receptors are further classified into three

types.

1 Cold receptors, which consist of free nerve endings of

lightly myelinated Aδ fibers.

2 Warmth receptors, which consist of the free nerve

endings of unmyelinated C fibers that respond to increases

in temperature.

3 Temperature-sensitive nociceptors that are sensitive to

excessive heat or cold.

Mechanoreceptors

Mechanoreceptors are activated following physical deformation of the skin,

muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules in which they reside

Mechanoreceptors, which comprise both exteroceptors and

proprioceptors, are activated following physical deformation

due to touch, pressure, stretch, or vibration of the skin,

muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules, in which they

reside. A mechanoreceptor may be classified as nonencapsulated

or encapsulated depending on whether a structural

device encloses its peripheral nerve ending component.

Nonencapsulated mechanoreceptors

Nonencapsulated mechanoreceptors are slowly adapting and include free

nerve endings and tactile receptors

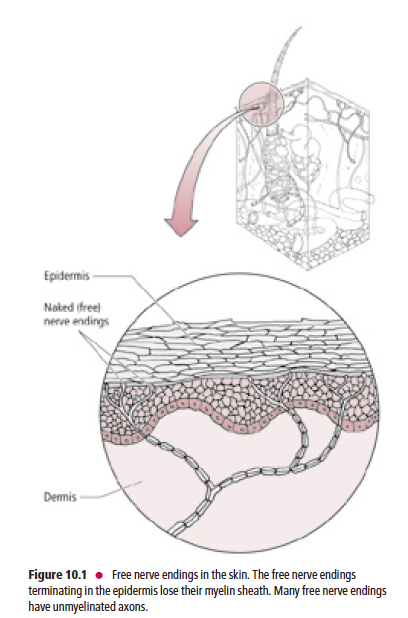

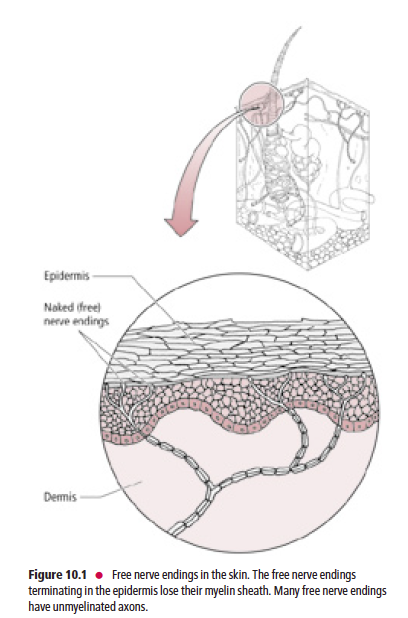

Free nerve endings (Fig. 10.1) are present in the epidermis, dermis, cornea, dental pulp, mucous membranes of the oral and nasal cavities and of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinary tracts, muscles, tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, and bones. The peripheral nerve terminals of the free nerve endings lack Schwann cells and myelin sheaths. They are stimulated by touch, pressure, thermal, or painful stimuli.

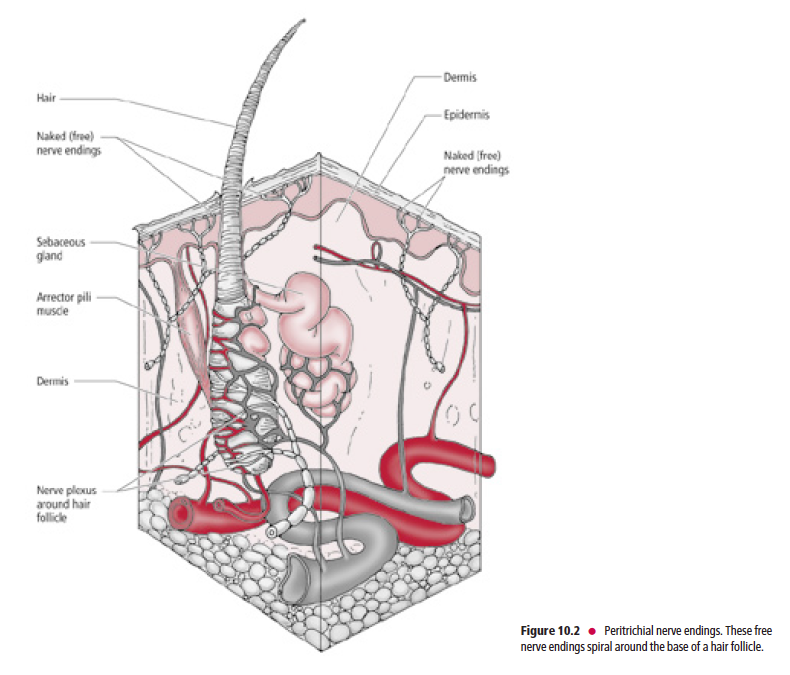

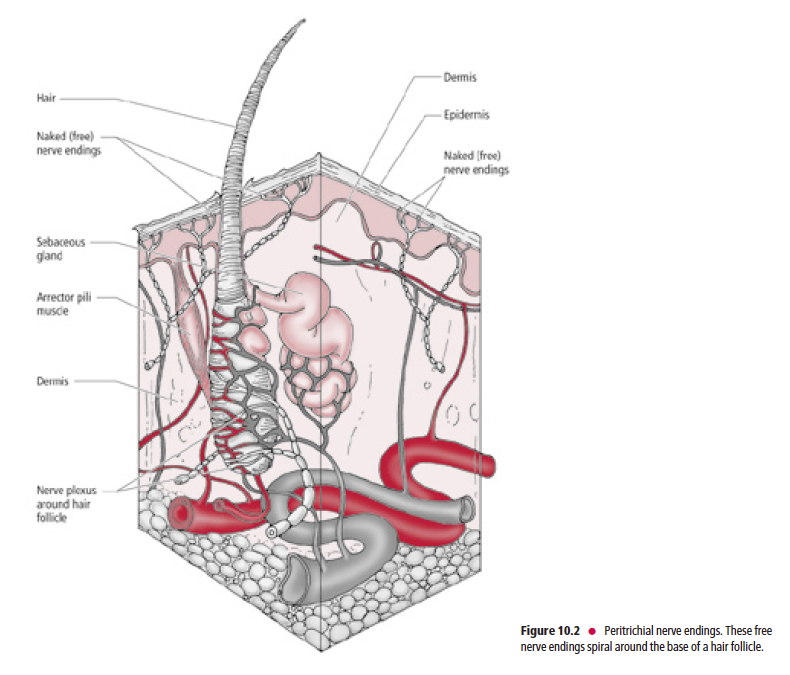

Peritrichial nerve endings (Fig. 10.2) are specialized members of this category. They are large-diameter, myelinated,

Aβ fibers that coil around a hair follicle below its associated sebaceous gland. This type of receptor is stimulated only

when a hair is being bent.

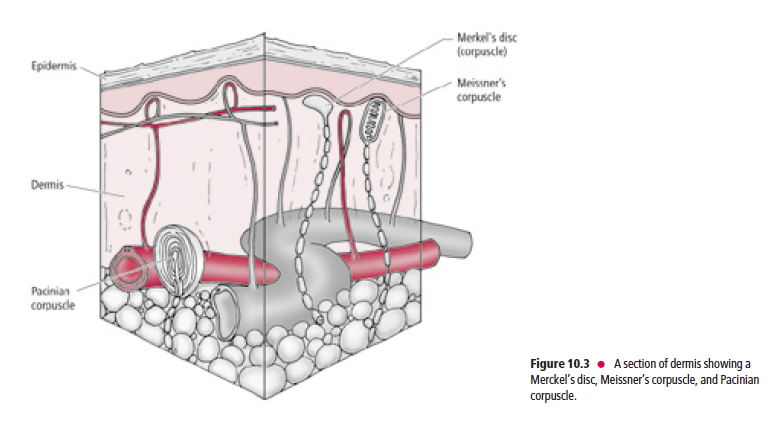

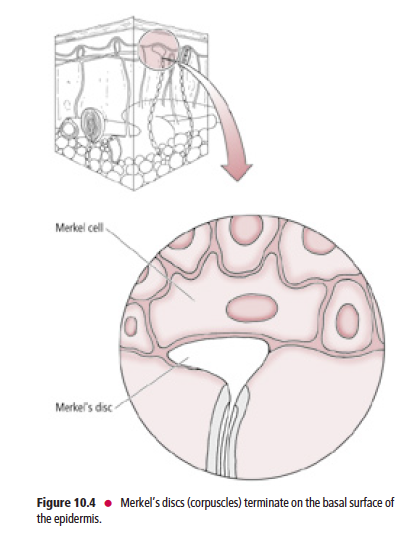

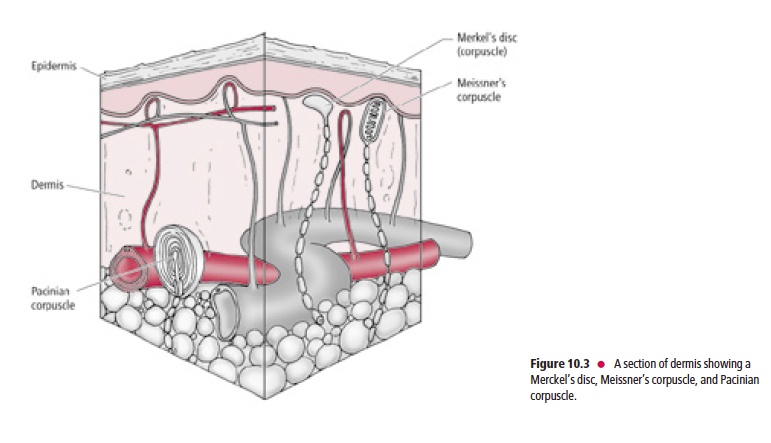

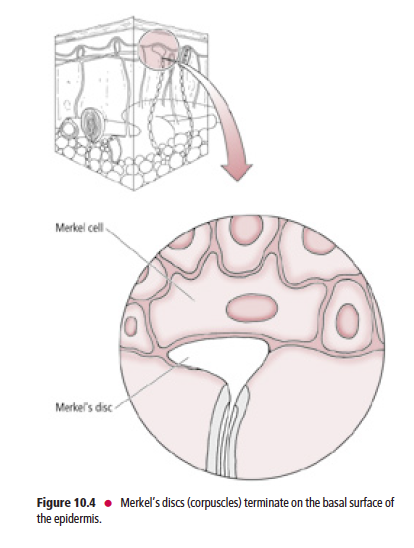

Tactile receptors (Fig. 10.3) consist of disc-shaped, peripheral nerve endings of large-diameter, myelinated, Aβ fibers.

Each disc-shaped terminal is associated with a specialized epithelial cell, the Merkel cell, located in the stratum basale

of the epidermis.

These receptors, frequently referred to as Merkel’s discs (Fig. 10.4), are present mostly in glabrous (hairless), and occasionally in hairy skin. Merkel’s discs respond to discriminative touch stimuli that facilitate the distinguishing of texture, shape, and edges of objects.

Encapsulated mechanoreceptors

Encapsulated mechanoreceptors include Meissner’s corpuscles, pacinian corpuscles, and Ruffini’s end organs.

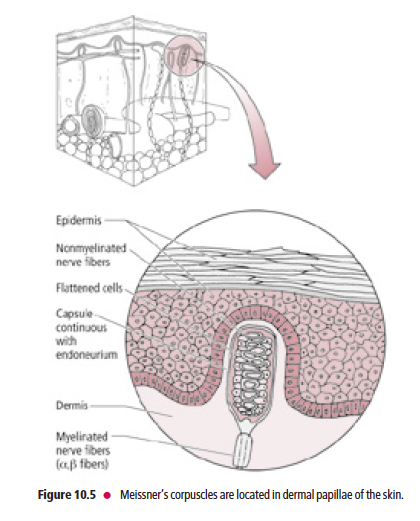

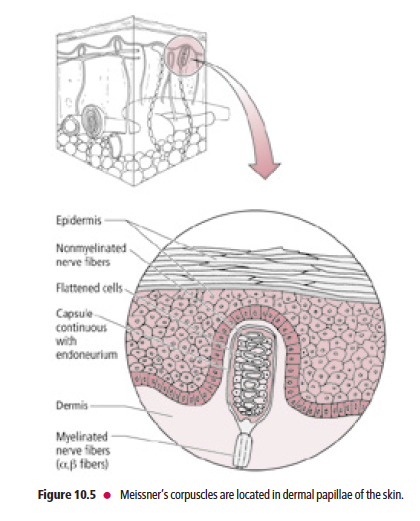

Meissner’s corpuscles are present in the dermal papillae of glabrous skin of the lips, forearm, palm, and sole, and in the connective tissue papillae of the tongue

Meissner’s corpuscles (Fig. 10.5) are present in the dermal papillae of glabrous skin of the lips, forearm, palm, and sole, as well as in the connective tissue papillae of the tongue. These corpuscles consist of the peripheral terminals of Aβ

fibers, which are encapsulated by a peanut-shaped structural device consisting of a stack of concentric Schwann cells

surrounded by a connective tissue capsule. They are rapidly adapting and are sensitive to two-point tactile (fine) discrimination, and are thus of great importance to the visually impaired by permitting them to be able to read Braille.

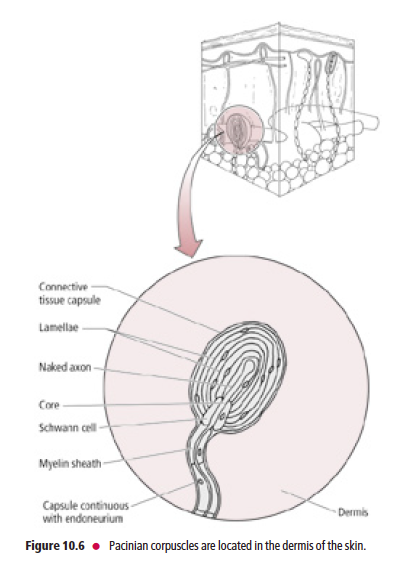

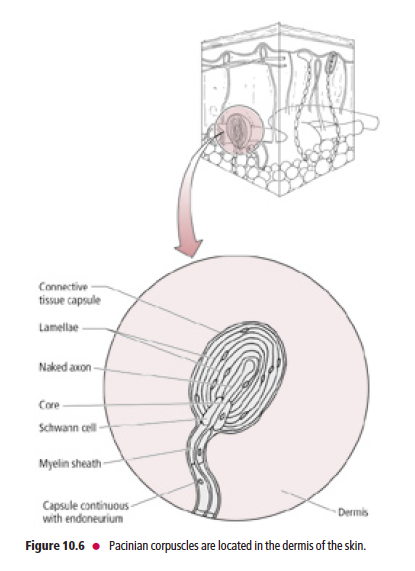

Pacinian corpuscles are the largest of the mechanoreceptors

Pacinian corpuscles (Fig. 10.6), the largest of the mechanoreceptors, are rapidly adapting and resemble an

onion in cross-section. Each Pacinian corpuscle consists of Aβ-fiber terminals encapsulated by layers of modified

fibroblasts that are enclosed in a connective tissue capsule. Pacinian corpuscles are located in the dermis, hypodermis,

interosseous membranes, ligaments, external genitalia, joint capsules, and peritoneum, as well as in the pancreas. They are more rapidly adapting than Meissner’s corpuscles and are believed to respond to pressure and vibratory stimuli,

including tickling sensations.

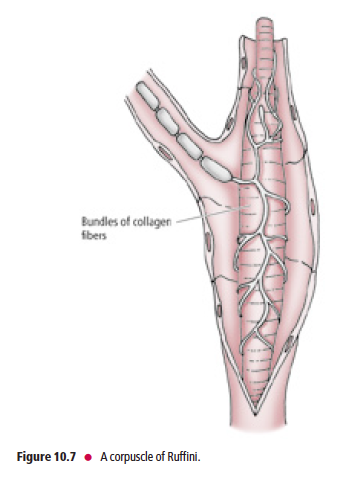

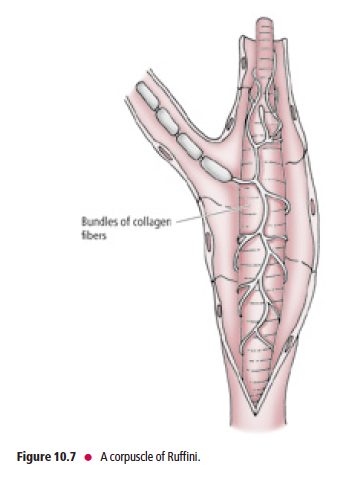

Ruffini’s end organs are located in the joint capsules, dermis, and underlying

hypodermis of hairy skin

Ruffini’s end organs (corpuscles of Ruffini) (Fig. 10.7) are located in joint capsules, the dermis, and the underlying

hypodermis of hairy skin. The unmyelinated peripheral terminals of Aβ myelinated fibers are slowly adapting. They

intertwine around the core of collagen fibers, which is surrounded by a lamellated cellular capsule. Ruffini’s end organs respond to stretching of the collagen bundles in the skin or joint capsules and may provide proprioceptive information. Muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs (GTOs) are also encapsulated mechanoreceptors, but, due to their specialized function, they are discussed separately.

Muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs

The mucle spindles and GTOs detect sensory input from the skeletal muscle and transmit it to the spinal cord

where it plays an important role in reflex activity and motor control involving the cerebellum. In addition, sensory input from these muscle receptors is also relayed to the cerebral cortex by way of the DCML pathway, which mediates information concerning posture, position sense, as well as movement and orientation of the body and its parts.

Muscle spindles

Structure and function

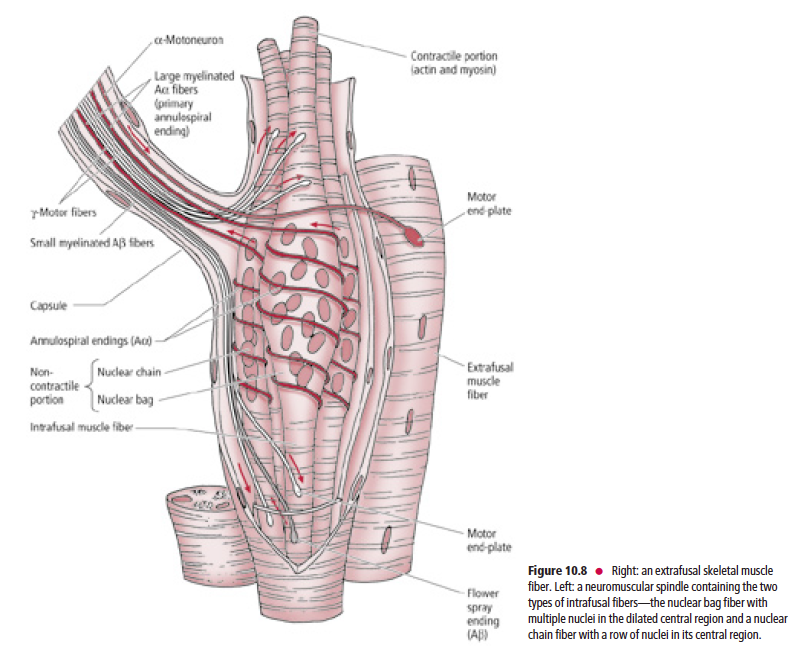

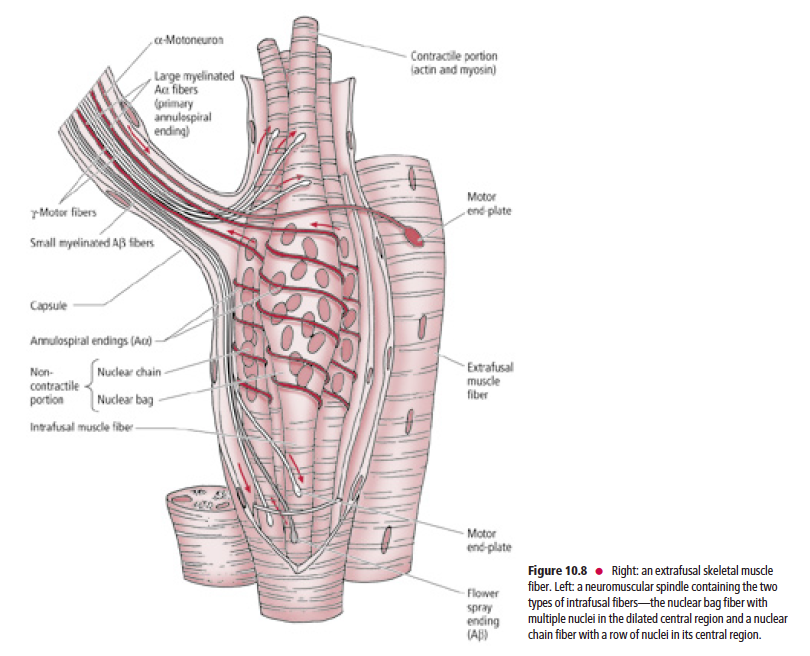

Skeletal muscle consists of extrafusal and intrafusal fibers

Extrafusal fibers are ordinary skeletal muscle cells constituting

the majority of gross muscle, and their stimulation results

in muscle contraction. Muscle spindles, composed of small

bundles of encapsulated intrafusal fibers, are dispersed

throughout gross muscle. These are dynamic stretch receptors

that continuously check for changes in muscle length.

Each muscle spindle is composed of two to 12 intrafusal

fibers enclosed in a slender capsule, which in turn is surrounded by an outer fusiform connective tissue capsule

whose tapered ends are attached to the connective tissue

sheath surrounding the extrafusal muscle fibers (Fig. 10.8).

The compartment between the inner and outer capsules contains

a glycosaminoglycan-rich viscous fluid.

There are two types of intrafusal fibers based on their

morphological characteristics: nuclear bag fibers and nuclear

chain fibers. Both nuclear bag and nuclear chain fibers possess

a central, noncontractile region housing multiple nuclei,

and a skeletal muscle (myofibril-containing) contractile portion

at each end of the central region. The nuclear bag fibers

are larger, and their multiple nuclei are clustered in the “baglike”

dilated central region of the fiber. The nuclear chain

fibers are smaller and consist of multiple nuclei arranged

sequentially, as in a “chain” of pearls, in the central region of

the fiber.

Each intrafusal fiber of a muscle spindle receives sensory innervation via the

peripheral processes of pseudounipolar sensory neurons

Each intrafusal fiber of a muscle spindle receives sensory

innervation via the peripheral processes of pseudounipolar

sensory neurons whose cell bodies are housed in dorsal root

ganglia, or in the sensory ganglia of the cranial nerves (and in

the case of the trigeminal nerve, within its mesencephalic

nucleus). Since the large-diameter Aα fibers spiral around the

noncontractile region of the intrafusal fibers, they are known

as annulospiral or primary endings. These endings become

activated at the beginning of muscle stretch or tension. In

addition to the annulospiral endings, the intrafusal fibers,

mainly the nuclear chain fibers, also receive smaller diameter,

Aβ peripheral processes of pseudounipolar neurons. These

nerve fibers terminate on both sides of the annulospiral ending,

are referred to as secondary or flower spray endings,

and are activated during the time that the stretch is in

progress (Fig. 10.8).

In addition to sensory innervation, intrafusal fibers also receive motor

innervation via gamma motoneurons that innervate the contractile portions

of the intrafusal fibers, causing them to contract In addition to the sensory innervation, intrafusal fibers

also receive motor innervation via gamma motoneurons

(fusimotor neurons) that innervate the contractile portions of

the intrafusal fibers, causing them to undergo contraction.

Since the intrafusal fibers are oriented parallel to the longitudinal

axis of the extrafusal fibers, when a muscle is stretched,

the central, noncontractile region of the intrafusal fibers is

also stretched, distorting and stimulating the sensory nerve

endings coiled around them, causing the nerve endings to

fire. However, when the muscle contracts, tension on the

central noncontractile region of the intrafusal fibers decreases

(which reduces the rate of firing of the sensory nerve endings

coiled around it).

During voluntary muscle activity simultaneous stimulation

of the extrafusal fibers by the alpha motoneurons, and

the contractile portions of the intrafusal fibers by the gamma

motoneurons, serves to modulate the sensitivity of the

intrafusal fibers. That is, the gamma motoneurons cause

corresponding contraction of the contractile portions of the

intrafusal fibers, which stretch the central noncontractile

region of the intrafusal fibers. Thus, the sensitivity of the

intrafusal fibers is constantly maintained by continuously

readapting to the most current status of muscle length. In this

fashion the muscle spindles can detect a change in muscle

length (resulting from stretch or contraction) irrespective of

muscle length at the onset of muscle activity. It should be

noted that even though they contract, the intrafusal fibers,

due to their small number and size, do not contribute to

any significant extent to the overall contraction of a gross

muscle.

Simple stretch reflex

The simple stretch reflex, whose mechanism is based on the

role of the intrafusal fibers, functions to maintain muscle

length caused by external disturbances. As a muscle is

stretched, the intrafusal fibers of the muscle spindles are

also stretched. This in turn stimulates the sensory afferent

annulospiral and flower spray endings to transmit this

information to those alpha motoneurons of the CNS (spinal

cord, or cranial nerve motor nuclei) that innervate the agonist

(stretched) muscle as well as to those motoneurons that

innervate the antagonist muscle(s). The degree of stretching

is proportional to (or related to) the load placed on the

muscle. The larger the load, the more strongly the spindles

are depolarized and the more extrafusal muscle fibers are in

turn activated. As these alpha motoneurons of the stretched

muscle fire, they stimulate the contraction of the required

number of extrafusal muscle fibers of the agonist muscle.

The alpha motoneurons of the antagonist muscle(s) are

inhibited so the antagonist muscle relaxes. The simple reflex

arc involves the firing of only two neurons—an afferent

sensory neuron and an efferent motoneuron—providing

dynamic information concerning the changes of the load

on the muscle and position of the body region in threedimensional

space.

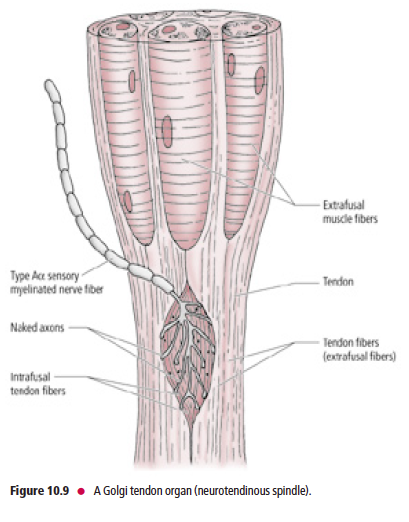

Golgi tendon organs

GTOs (neurotendinous spindles) are fusiform-shaped receptors located at

sites where muscle fibers insert into tendons

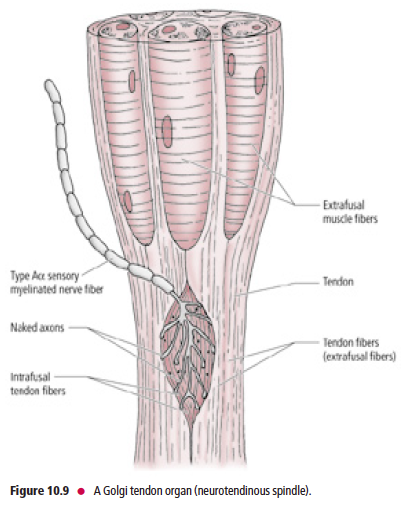

Unlike muscle spindles, which are oriented parallel to the longitudinal axis of the extrafusal muscle fibers, GTOs are in series. Furthermore, GTOs do not receive motor innervation as the muscle spindles do. GTOs consist of interlacing intrafusal collagen bundles enclosed in a connective tissue capsule (Fig. 10.9).

A large-diameter, type Aα sensory fiber,

whose cell body is housed in a dorsal root sensory ganglion

or a cranial nerve sensory ganglion, passes through the

capsule and then branches into numerous delicate terminals

that are interposed among the intrafusal collagen bundles.

The central processes of these Aα afferent neurons enter

the spinal cord via the dorsal roots of the spinal nerves to

terminate and establish synaptic contacts with inhibitory

interneurons that, in turn, synapse with alpha motoneurons

supplying the contracted agonist muscle.

Combined muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ

functions during changes in muscle length

During slight stretching of a relaxed muscle, the muscle spindles are

stimulated while the GTOs remain undisturbed and quiescent; with further

stretching both the muscle spindles and GTOs are stimulated During muscle contraction, as the muscle shortens, tension

is produced in the tendons anchoring that muscle to bone,

compressing the nerve fiber terminals interposed among the

inelastic intrafusal collagen fibers. This compression activates

the sensory terminals in the GTOs, which transmit this

sensory information to the CNS, providing proprioceptive

information concerning muscle activity and preventing the

placement of excessive forces on the muscle and tendon. In

contrast, the noncontractile portions of the muscle spindles

are not stretched, and are consequently undisturbed. The

contractile regions of the muscle spindles, however, undergo

corresponding contraction that enables them to detect a

future change in muscle length (resulting from stretch or

contraction).

During slight stretching of a relaxed muscle, the muscle

spindles are stimulated whereas the GTOs remain undisturbed

and quiescent. During further stretching of the

muscle, which produces tension on the tendons, both

the muscle spindles and the GTOs are stimulated. Thus

GTOs monitor and check the amount of tension exerted on

the muscle (regardless of whether it is tension generated by

muscle stretch or contraction), whereas muscle spindles

check muscle fiber length and rate of change of muscle length

(during muscle stretch or contraction).

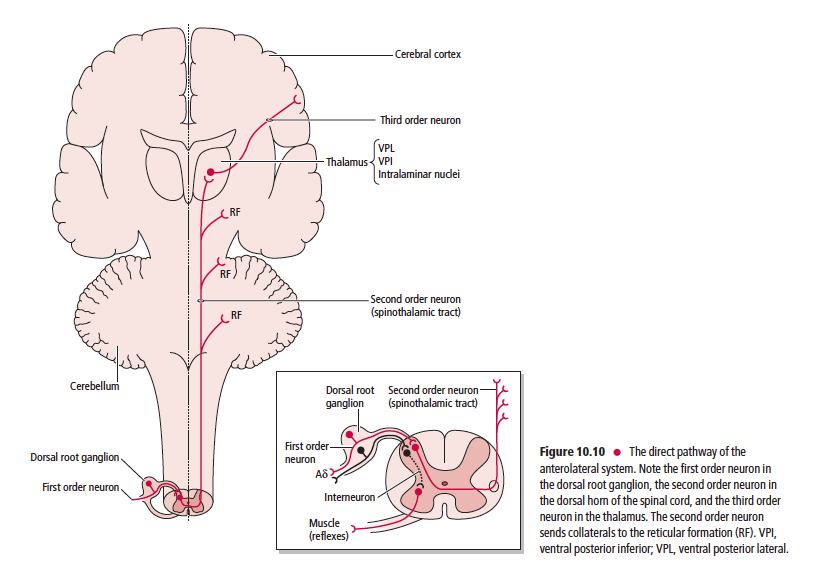

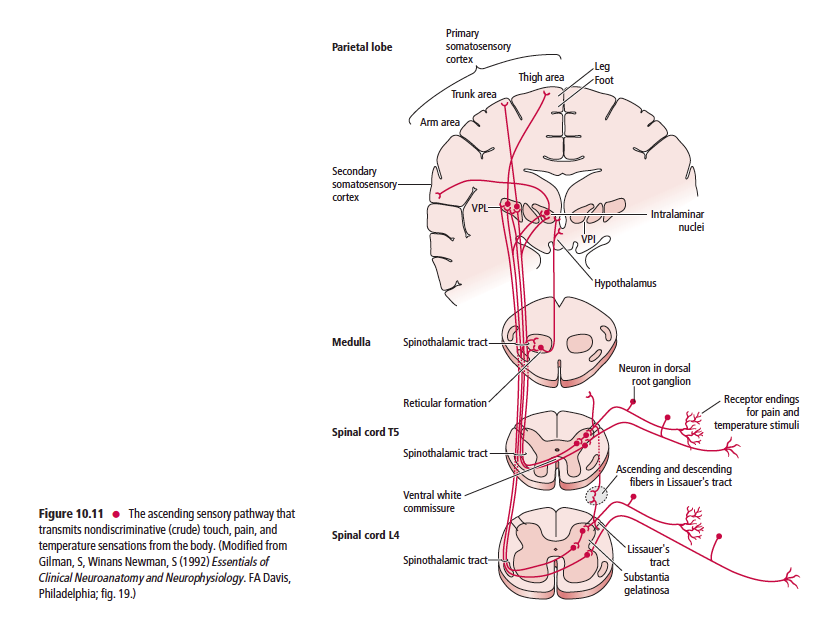

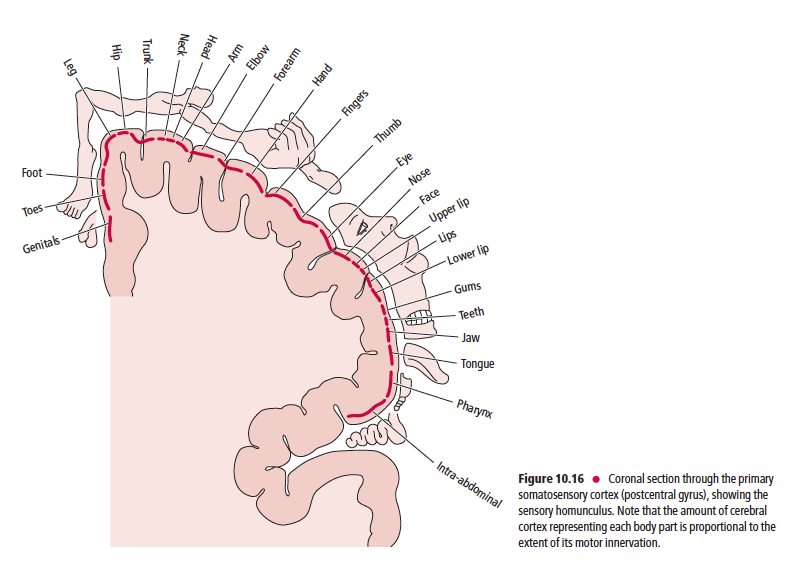

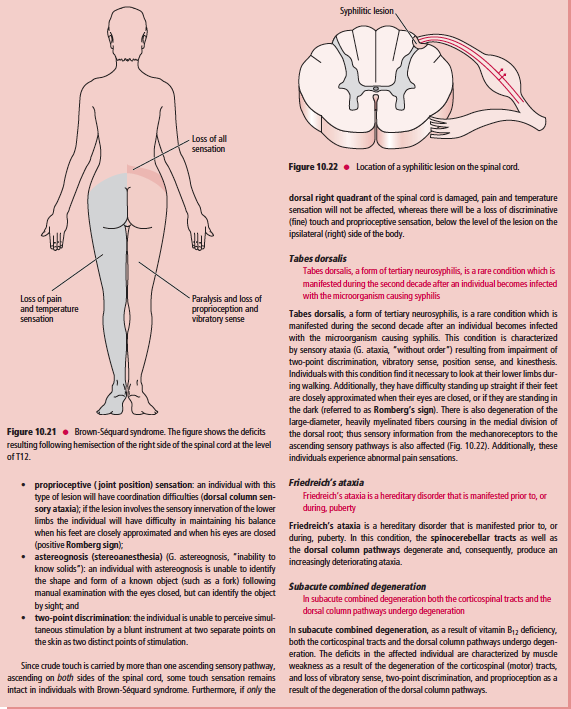

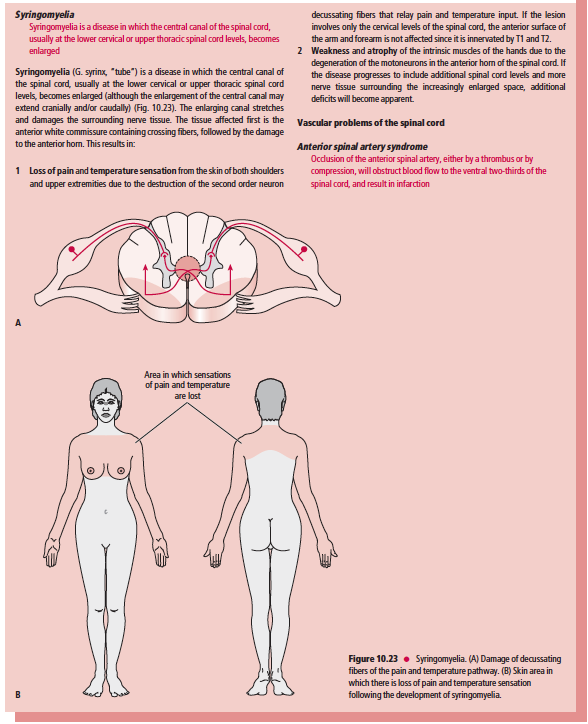

이후 중추신경전달은 그림만 올림.