Re: Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis - nature 리뷰

작성자문형철작성시간20.08.24조회수864 목록 댓글 0beyond reason

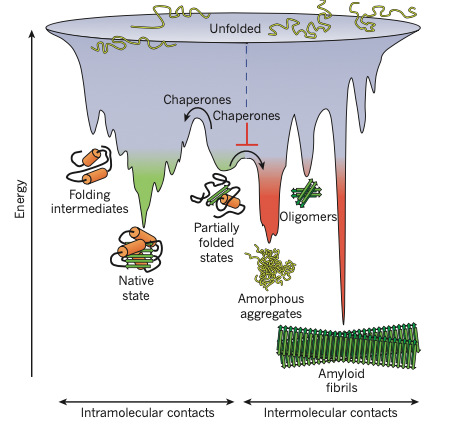

Figure1|Competing reactions of protein folding and aggregation. Scheme of the funnel-shaped free-energy surface that proteins explore as they move towards the native state (green) by forming intramolecular contacts (modified from refs 19 and 95). The ruggedness of the free-energy landscape results in the accumulation of kinetically trapped conformations that need to traverse free-energy barriers to reach a favourable downhill path. In vivo, these steps may be accelerated by chaperones . When several molecules fold

simultaneously in the same compartment, the free-energy surface of folding may overlap with that of intermolecular aggregation, resulting in the formation of amorphous aggregates, toxic oligomers or ordered amyloid fibrils (red). Fibrillar aggregation typically occurs by nucleation-dependent polymerization. It may initiate from intermediates populated during de novo folding or after destabilization of the native state (partially folded states) and is normally prevented by molecular chaperones.

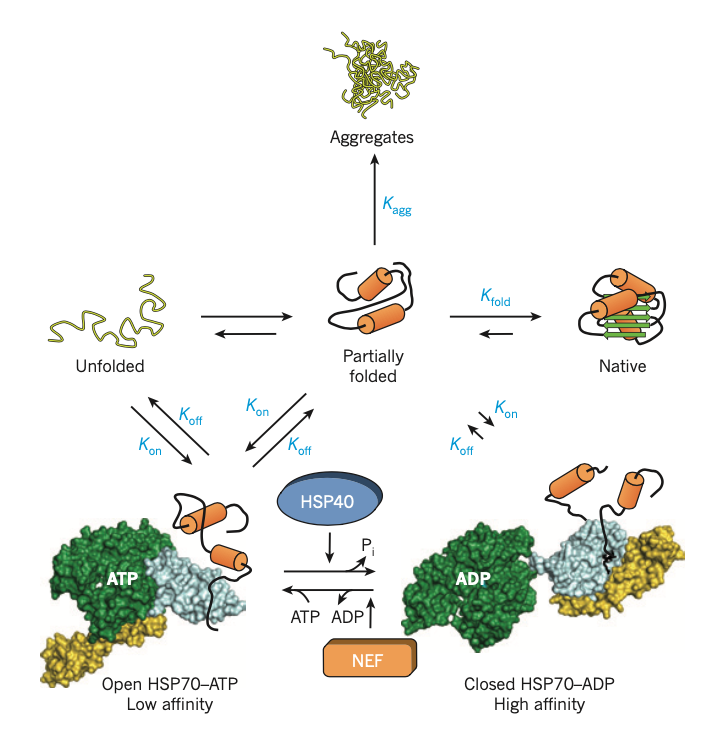

Figure2|The HSP70 chaperone cycle. HSP70 is switched between high- and low-affinity states for unfolded and partially folded protein by ATP binding and hydrolysis. Unfolded and partially folded substrate (nascent chain or stress-denatured protein), exposing hydrophobic peptide segments, is delivered to ATP-bound HSP70 (open; low substrate affinity with high on-rates and off-rates) by one of several HSP40 cofactors. The hydrolysis of ATP, which is accelerated by HSP40, results in closing of the α-helical lid of the peptide-binding domain (yellow) and tight binding of substrate by HSP70 (closed; high affinity with low on-rates and off-rates). Dissociation of ADP catalysed by one of several nucleotide-exchange factors (NEFs) is required for recycling. Opening of the α-helical lid, induced by ATP binding, results

in substrate release. Folding is promoted and aggregation is prevented when both the folding rate constant (Kfold) is greater than the association constant (Kon) for chaperone binding (or rebinding) of partially folded states, and Kon is greater than intermolecular association by the higher-order aggregation rate constant Kagg (Kfold > Kon > Kagg) (kinetic partitioning). For proteins that populate misfolded states, Kon may be greater than Kfold (Kfold ≤ Kon > Kagg). These proteins are stabilized by HSP70 in a non-aggregated state, but require

14,20

transfer into the chaperonin cage for folding . After conformational stress,

Kagg may become faster than Kon, and aggregation occurs (Kagg > Kon ≥ Kfold), unless chaperone expression is induced via the stress-response pathway. Structures in this figure relate to Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession codes 1DKG, 1DKZ, 2KHO and 2QXL. Pi, inorganic phosphate.

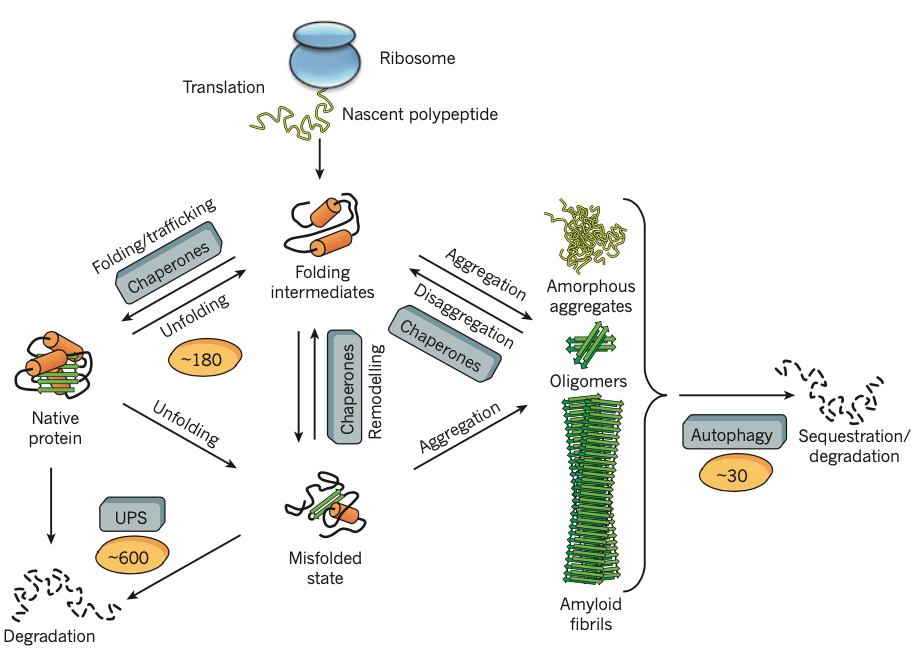

Figure 6 | Protein fates in the proteostasis network. The proteostasis network integrates chaperone pathways for the folding of newly synthesized proteins, for the remodelling of misfolded states and for disaggregation with the protein degradation mediated by the UPS and the autophagy

system. Approximately 180 different chaperone components and their regulators orchestrate these processes

in mammalian cells, whereas the UPS comprises ~600 and the autophagy system ~30 different components.

The primary effort of the chaperone system is in preventing aggregation,

but machinery for the disaggregation of aggregated proteins has been described in bacteria and fungi, involving oligomeric AAA+-proteins such as HSP104 and the E. coli molecular chaperone protein ClpB, which 25 cooperatewithHSP70chaperones .

A similar activity has been detected

in metazoans, but the components involved have not yet been defined

Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis

- F. Ulrich Hartl,

- Andreas Bracher &

- Manajit Hayer-Hartl

Nature volume 475, pages324–332(2011)Cite this article

10k Accesses

1642 Citations

40 Altmetric

Abstract

Most proteins must fold into defined three-dimensional structures to gain functional activity. But in the cellular environment, newly synthesized proteins are at great risk of aberrant folding and aggregation, potentially forming toxic species.

To avoid these dangers, cells invest in a complex network of molecular chaperones, which use ingenious mechanisms to prevent aggregation and promote efficient folding. Because protein molecules are highly dynamic, constant chaperone surveillance is required to ensure protein homeostasis (proteostasis). Recent advances suggest that an age-related decline in proteostasis capacity allows the manifestation of various protein-aggregation diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Interventions in these and numerous other pathological states may spring from a detailed understanding of the pathways underlying proteome maintenance.