Cell

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 Mar 9.

Published in final edited form as: Cell. 2017 Mar 9;168(6):960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004

mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease

Robert A Saxton 1,2,3,4, David M Sabatini 1,2,3,4,*

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC5394987 NIHMSID: NIHMS850540 PMID: 28283069

The publisher's version of this article is available at Cell

This article has been corrected. See Cell. 2017 Apr 6;169(2):361.

Abstract

The mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) coordinates eukaryotic cell growth and metabolism with environmental inputs including nutrients and growth factors. Extensive research over the past two decades has established a central role for mTOR in regulating many fundamental cell processes, from protein synthesis to autophagy, and deregulated mTOR signaling is implicated in the progression of cancer and diabetes, as well as the aging process. Here, we review recent advances in our understanding of mTOR function, regulation, and importance in mammalian physiology. We also highlight how the mTOR-signaling network contributes to human disease, and discuss the current and future prospects for therapeutically targeting mTOR in the clinic.

요약

mTOR(mechanistic Target of Rapamycin)는

영양소 및 성장 인자를 포함한 환경적 요인과 진핵세포의 성장 및 대사를 조율합니다.

지난 20년 동안의 광범위한 연구를 통해

mTOR가 단백질 합성에서 자가포식에 이르기까지

여러 기본적인 세포 과정을 조절하는 데 핵심적인 역할을 한다는 것이 밝혀졌으며,

mTOR 신호 전달의 조절 장애는 암과 당뇨병의 진행은 물론 노화 과정에도 관련이 있는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.

본 논문에서는

mTOR의 기능, 조절 메커니즘, 포유류 생리학에서의 중요성에 대한

최근 연구 성과를 검토합니다.

또한

mTOR 신호전달 네트워크가 인간 질환에 미치는 영향을 강조하며,

임상에서 mTOR를 표적으로 한 치료법의 현재 및 미래 전망을 논의합니다.

Introduction

In 1964 a Canadian expedition to the isolated South Pacific island of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) collected a set of soil samples with the goal of identifying novel antimicrobial agents. In bacteria isolated from one of these samples, Sehgal and colleagues discovered a compound with remarkable antifungal, immunosuppressive, and antitumor properties (Eng et. al. 1984; Martel et. al. 1977; Vezina et. al 1975). Further analysis of this compound, named rapamycin after its site of discovery (clinically referred to as sirolimus), revealed that it acts in part by forming a gain of function complex with the peptidyl-prolyl-isomerase FKBP12 to inhibit signal transduction pathways required for cell growth and proliferation (Chung et. al., 1992).

Despite these insights, the full mechanism of action of rapamycin remained elusive until 1994 when biochemical studies identified the mechanistic (formerly “mammalian”) Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) as the direct target of the rapamycin-FKBP12 complex in mammals (Brown et. al. 1994; Sabatini et. al. 1994; Sabers et. al 1995), and revealed it to be the homolog of the yeast TOR/DRR genes that had previously been identified in genetic screens for rapamycin resistance (Cafferkey et. al. 1993; Heitman et. al. 1991; Kunz et. al. 1993).

In the more than two decades since these discoveries, studies from dozens of labs across the globe have revealed that the mTOR protein kinase nucleates a major eukaryotic signaling network that coordinates cell growth with environmental conditions and plays a fundamental role in cell and organismal physiology. Many aspects of mTOR function and regulation have only recently been elucidated, and many more questions remain unanswered. In this review, we provide an overview of our current understanding of the mTOR pathway and its role in growth, metabolism, and disease.

서론

1964년 캐나다 탐험대가 고립된 남태평양의 라파 누이 섬(이스터 섬으로도 알려져 있음)에서 새로운 항균 물질을 식별하기 위해 토양 샘플을 채취했습니다. 이 샘플 중 하나에서 분리된 세균에서 세갈과 동료들은 항진균, 면역억제, 항종양 효과를 지닌 화합물을 발견했습니다(Eng et al. 1984; Martel et al. 1977; Vezina et al. 1975). 이 화합물은 발견 장소에서 이름을 따서 라파마이신(임상적으로 시롤리무스라고도 함)으로 명명되었으며, 추가 분석 결과 이 화합물은 펩티딜-프로릴-이소메라제 FKBP12와 기능 획득 복합체를 형성하여 세포 성장 및 증식에 필요한 신호 전달 경로를 억제하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다(Chung et al., 1992).

이러한 통찰에도 불구하고, 라파마이신의 작용 메커니즘은 1994년까지 명확히 밝혀지지 않았습니다. 당시 생화학적 연구를 통해 라파마이신-FKBP12 복합체의 직접적인 표적으로서 'mTOR'(이전에는 '포유류 표적'으로 불렸음)가 식별되었습니다(Brown et al. 1994; Sabatini et al. 1994; Sabers et al. 1995), 또한 이는 이전에 라파마이신 저항성 유전적 스크린에서 식별된 효모의 TOR/DRR 유전자와 동형체임을 밝혀냈습니다(Cafferkey et al. 1993; Heitman et al. 1991; Kunz et al. 1993).

이러한 발견 이후 20년 이상 동안 전 세계 수십 개의 연구소에서 진행한 연구에 따르면, mTOR 단백질 키나아제는 세포의 성장을 환경 조건과 조율하고 세포 및 유기체 생리학에 근본적인 역할을 하는 주요 진핵 생물 신호 전달 네트워크의 핵을 형성하는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. mTOR의 기능과 조절 메커니즘의 많은 측면은 최근에야 밝혀졌으며, 여전히 많은 질문이 남아 있습니다. 이 리뷰에서는 mTOR 경로의 현재 이해 상태와 성장, 대사, 질병에서의 역할을 개괄적으로 설명합니다.

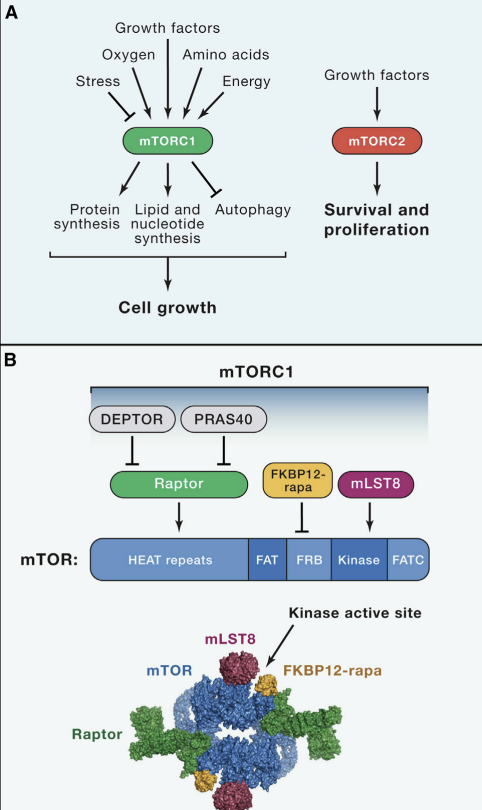

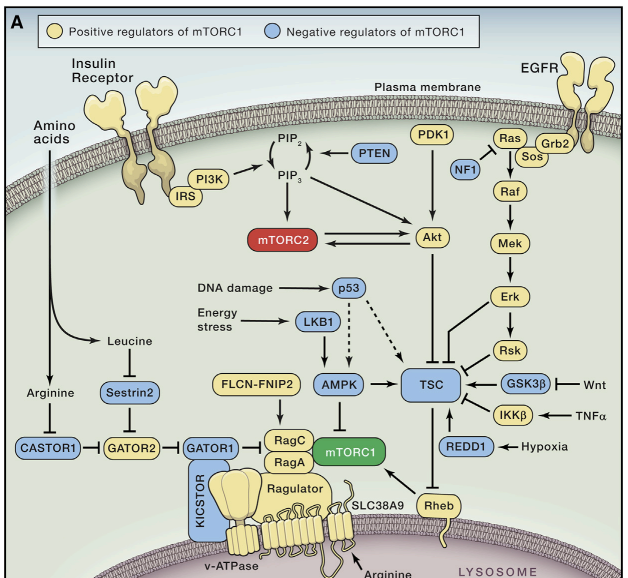

mTORC1 and mTORC2

mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase in the PI3K-related kinase (PIKK) family that forms the catalytic subunit of two distinct protein complexes, known as mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) and 2 (mTORC2) (Fig. 1A). mTORC1 is defined by its three core components: mTOR, Raptor (regulatory protein associated with mTOR), and mLST8 (mammalian lethal with Sec13 protein 8, also known as GβL) (Fig. 1B, Kim et al. 2002; Hara et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2003). Raptor facilitates substrate recruitment to mTORC1 through binding to the TOR signaling (TOS) motif found on several canonical mTORC1 substrates (Nojima et al., 2003; Schalm et al., 2003), and, as described later, is required for the correct subcellular localization of mTORC1. mLST8 by contrast associates with the catalytic domain of mTORC1 and may stabilize the kinase activation loop (Yang et al. 2013), though genetic studies suggest it is dispensible for the essential functions of mTORC1 (Guertin et al., 2006). In addition to these three core components, mTORC1 also contains the two inhibitory subunits PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa) (Sancak et al. 2007; Vander Haar et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007) and DEPTOR (DEP domain containing mTOR interacting protein) (Peterson et al. 2009).

mTORC1 및 mTORC2

mTOR는 PI3K 관련 키나아제 (PIKK) 가족에 속하는 세린/트레오닌 단백질 키나아제로, 두 개의 서로 다른 단백질 복합체인 mTOR 복합체 1 (mTORC1)과 2 (mTORC2)의 촉매 서브유닛을 형성합니다 (그림 1A). mTORC1은 세 가지 핵심 구성 요소로 정의됩니다: mTOR, Raptor(mTOR와 연관된 조절 단백질), 및 mLST8(Sec13 단백질 8과 연관된 포유류 치사 단백질, GβL로도 알려져 있음)(그림 1B, Kim et al. 2002; Hara et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2003). Raptor는 여러 표준 mTORC1 기질에 존재하는 TOR 신호전달(TOS) 모티프에 결합하여 기질의 mTORC1 결합을 촉진하며(Nojima et al., 2003; Schalm et al., 2003), 후술할 바와 같이 mTORC1의 정확한 세포 내 국소화에 필수적입니다. mLST8은 반면 mTORC1의 촉매 도메인과 결합하며 키나아제 활성화 루프를 안정화시킬 수 있습니다(Yang et al. 2013), 그러나 유전적 연구는 mTORC1의 필수 기능에 필수적이지 않음을 시사합니다(Guertin et al., 2006). 이 세 가지 핵심 구성 요소 외에도 mTORC1은 두 개의 억제성 서브유닛인 PRAS40(프로린 풍부한 Akt 기질 단백질 40kDa) (Sancak et al. 2007; Vander Haar et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007)과 DEPTOR(DEP 도메인 포함 mTOR 상호작용 단백질) (Peterson et al. 2009)를 포함합니다.

Figure 1. mTORC1 and mTORC2.

(A) The mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling pathways.

(B) mTORC1 subunits and respective binding sites on mTOR. The FKBP12-rapamycin. The 5.9 Å cryo-EM structure of mTORC1 (without DEPTOR and PRAS40, PDB ID: 5FLC) from is depicted as a space filling model and colored by subunit.

(C) mTORC2 subunits and respective binding sites on mTOR.

Structural studies of mTORC1 have yielded significant insights into its assembly, function, and perturbation by rapamycin. Cryo-EM reconstructions of both mTORC1 and yeast TORC1 have revealed that the complex forms a 1 mDa “lozenge”-shaped dimer, with the dimerization interface comprised of contacts between the mTOR HEAT repeats as well as between Raptor and mTOR (Fig. 1B, Aylett et al. 2016; Baretic et al., 2016; Yip et al. 2010). In addition, a crystal structure of the mTOR kinase domain bound to mLST8 showed that the rapamycin-FKBP12 complex binds to the FRB domain of mTOR to narrow the catalytic cleft and partially occlude substrates from the active site (Yang et al., 2013).

While the rapamycin-FKBP12 complex directly inhibits mTORC1, mTORC2 is characterized by its insensitivity to acute rapamycin treatment. Like mTORC1, mTORC2 also contains mTOR and mLST8 (Fig. 1C). Instead of Raptor however, mTORC2 contains Rictor (rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR), an unrelated protein that likely serves an analogous function (Jacinto et al. 2004; Sarbassov et al. 2004). mTORC2 also contains DEPTOR (Peterson et al. 2009), as well as the regulatory subunits mSin1 (Frias et al. 2006; Jacinto et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2006) and Protor1/2 (Pearce et al. 2007; Thedieck et al. 2007; Woo et al., 2007). Although rapamycin-FKBP12 complexes do not directly bind or inhibit mTORC2, prolonged rapamycin treatment does abrogate mTORC2 signaling, likely due to the inability of rapamycin-bound mTOR to incorporate into new mTORC2 complexes (Lamming et al., 2012).

mTORC1의 구조적 연구는 그 조립, 기능, 그리고 라파마이신에 의한 교란에 대한 중요한 통찰을 제공했습니다. mTORC1과 효모 TORC1의 크리오-EM 재구성 결과, 이 복합체가 1 mDa 크기의 '로젠지' 모양의 이량체로 형성되며, 이량체화 인터페이스는 mTOR HEAT 반복 구조 간의 접촉 및 Raptor와 mTOR 간의 접촉으로 구성되어 있음을 보여주었습니다 (Fig. 1B, Aylett et al. 2016; Baretic et al., 2016; Yip et al. 2010). 또한, mTOR 키나아제 도메인과 mLST8이 결합된 결정 구조는 라파마이신-FKBP12 복합체가 mTOR의 FRB 도메인에 결합하여 촉매 틈새를 좁히고 활성 부위에서 기질의 접근을 부분적으로 차단함을 보여주었습니다(Yang et al., 2013).

라파마이신-FKBP12 복합체는 mTORC1을 직접 억제하지만, mTORC2는 급성 라파마이신 치료에 대한 감수성이 없습니다. mTORC1과 마찬가지로 mTORC2도 mTOR와 mLST8을 포함합니다(그림 1C). 그러나 Raptor 대신 mTORC2는 mTOR의 라파마이신 불감성 동반 단백질인 Rictor를 포함하며, 이 단백질은 유사한 기능을 수행할 것으로 추정됩니다(Jacinto et al. 2004; Sarbassov et al. 2004). mTORC2는 또한 DEPTOR (Peterson et al. 2009)를 포함하며, 조절 서브유닛인 mSin1 (Frias et al. 2006; Jacinto et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2006)과 Protor1/2 (Pearce et al. 2007; Thedieck et al. 2007; Woo et al., 2007). 라파마이신-FKBP12 복합체는 mTORC2에 직접 결합하거나 억제하지 않지만, 장기간의 라파마이신 치료는 mTORC2 신호전달을 억제하며, 이는 라파마이신에 결합된 mTOR가 새로운 mTORC2 복합체에 통합되지 못하기 때문일 가능성이 높습니다 (Lamming et al., 2012).

The mTOR Signaling NetworkDownstream of mTORC1

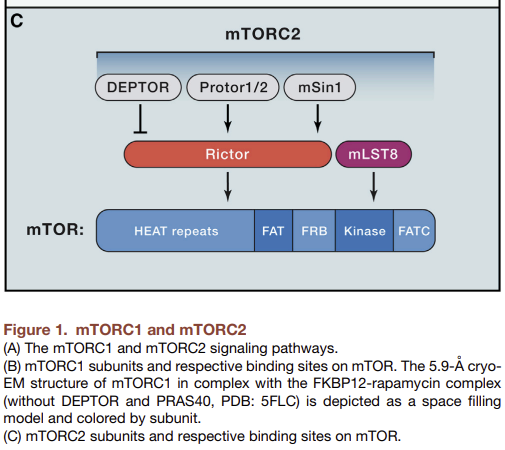

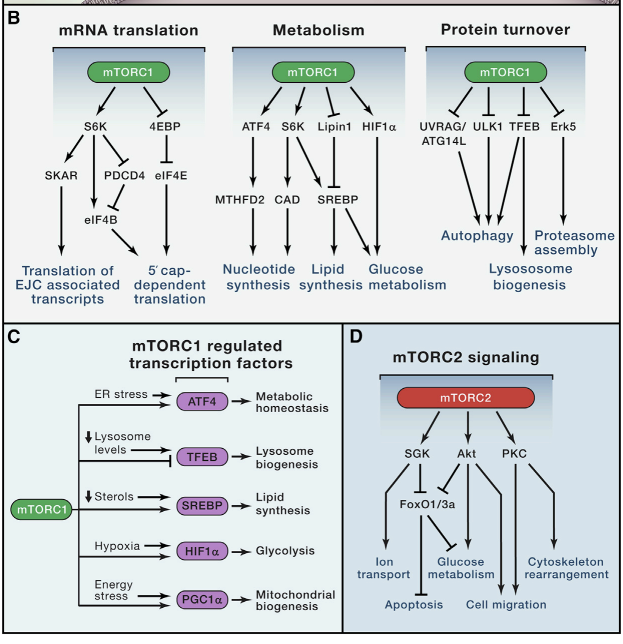

In order to grow and divide, cells must increase production of proteins, lipids, and nucleotides while also suppressing catabolic pathways such as autophagy. mTORC1 plays a central role in regulating all of these processes, and therefore controls the balance between anabolism and catabolism in response to environmental conditions (Fig. 2, A and B). Here we review the critical substrates and cellular processes downstream of mTORC1 and how they contribute to cell growth. Most of the functions discussed here were identified and characterized in the context of mammalian cell lines, while the physiological context in which these processes are important will be discussed in greater detail later.

mTOR 신호 전달 네트워크 mTORC1의 하류

세포는 성장과 분열을 위해 단백질, 지질, 뉴클레오티드의 생성을 증가시키는 동시에 자가포식 등 이화 작용을 억제해야 합니다. mTORC1은 이러한 모든 과정을 조절하는 중심적인 역할을 하며, 따라서 환경 조건에 반응하여 동화 작용과 이화 작용의 균형을 제어합니다 (그림 2, A 및 B). 이 글에서는 mTORC1 하류의 핵심 기질과 세포 과정, 그리고 이들이 세포 성장에 어떻게 기여하는지 검토합니다. 여기서 논의된 대부분의 기능은 포유류 세포 계통에서 식별되고 특성화되었으며, 이러한 과정이 중요한 생리학적 맥락은 나중에 더 자세히 논의될 것입니다.

Figure 2. The mTOR Signaling Network.

(A) The signaling pathways upstream of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Positive regulators of mTORC1 signaling are shown in yellow, while negative regulators are shown in blue. mTORC1 and mTORC2 are shown in green and red, respectively.

(B) The major signaling pathways downstream of mTORC1 signaling in mRNA translation, metabolism, and protein turnover.

(C) mTORC1 controls the activity of several transcription factors that can also be independently regulated by cell stress.

(D) The major signaling pathways downstream of mTORC2 signaling.

Protein synthesis

mTORC1 promotes protein synthesis largely through the phosphorylation of two key effectors, p70S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) and eIF4E Binding Protein (4EBP) (Fig 2B). mTORC1 directly phosphorylates S6K1 on its hydrophobic motif site, Thr389, enabling its subsequent phosphorylation and activation by PDK1. S6K1 phosphorylates and activates several substrates that promote mRNA translation initiation including eIF4B, a positive regulator of the 5′cap binding eIF4F complex (Holz et al., 2005). S6K1 also phosphorylates and promotes the degradation of PDCD4, an inhibitor of eIF4B (Dorello et al. 2006), and enhances the translation efficiency of spliced mRNAs via its interaction with SKAR, a component of exon-junction complexes (Ma et al., 2008).

The mTORC1 substrate 4EBP is unrelated to S6K1 and inhibits translation by binding and sequestering eIF4E to prevent assembly of the eIF4F complex. mTORC1 phosphorylates 4EBP at multiple sites to trigger its dissociation from eIF4E (Brunn et al., 1997; Gingras et al. 1999), allowing 5′cap-dependent mRNA translation to occur. Although it has long been appreciated that mTORC1 signaling regulates mRNA translation, whether and how it affects specific classes of mRNA transcripts has been debated. Global ribosome foot printing analyses however revealed that while acute mTOR inhibition moderately suppresses general mRNA translation, it most profoundly affects mRNAs containing pyrimidine-rich 5′ TOP or “TOP-like” motifs, which includes most genes involved in protein synthesis (Hsieh et al. 2012; Thoreen et al. 2012).

단백질 합성

mTORC1은 두 가지 주요 효과인자, p70S6 키나아제 1 (S6K1)과 eIF4E 결합 단백질 (4EBP)의 인산화를 통해 단백질 합성을 주로 촉진합니다 (그림 2B). mTORC1은 S6K1의 친수성 모티프 부위인 Thr389를 직접 인산화하여 PDK1에 의한 후속 인산화와 활성화를 가능하게 합니다. S6K1은 eIF4B를 포함한 mRNA 번역 시작을 촉진하는 여러 기질 단백질을 인산화하고 활성화합니다. eIF4B는 5′캡 결합 eIF4F 복합체의 긍정적 조절인자입니다 (Holz et al., 2005). S6K1은 또한 eIF4B의 억제제인 PDCD4를 인산화하고 분해하며 (Dorello et al. 2006), exon-junction 복합체의 구성 요소인 SKAR와의 상호작용을 통해 분할된 mRNA의 번역 효율을 향상시킵니다 (Ma et al., 2008).

mTORC1의 기질인 4EBP는 S6K1과 무관하며, eIF4E에 결합하여 eIF4F 복합체의 조립을 방지함으로써 번역을 억제합니다. mTORC1은 4EBP를 다중 부위에서 인산화하여 eIF4E로부터의 분리를 유발합니다(Brunn et al., 1997; Gingras et al. 1999), 이는 5′캡 의존적 mRNA 번역이 발생하도록 합니다. mTORC1 신호전달이 mRNA 번역을 조절한다는 것은 오래전부터 알려져 왔지만, 특정 종류의 mRNA 전사물에 미치는 영향과 그 메커니즘은 논란의 대상이었습니다. 전사체 리보솜 발자국 분석 결과, 급성 mTOR 억제는 일반적인 mRNA 번역을 중간 정도 억제하지만, 피리미딘 풍부한 5′ TOP 또는 “TOP 유사” 모티프를 포함하는 mRNA에 가장 크게 영향을 미치며, 이는 단백질 합성에 관여하는 대부분의 유전자(Hsieh et al. 2012; Thoreen et al. 2012)를 포함합니다.

Lipid, nucleotide, and glucose metabolism

Growing cells require sufficient lipids for new membrane formation and expansion. mTORC1 promotes de novo lipid synthesis through the sterol responsive element binding protein (SREBP) transcription factors, which control the expression of metabolic genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis (Porstmann et al., 2008). While SREBP is canonically activated in response to low sterol levels, mTORC1 signaling can also activate SREBP independently through both an S6K1-dependent mechanism (Duvel et al., 2010) as well as through the phosphorylation of an additional substrate, Lipin1, which inhibits SREBP in the absence of mTORC1 signaling (Peterson et al., 2011).

Recent studies established that mTORC1 also promotes the synthesis of nucleotides required for DNA replication and ribosome biogenesis in growing and proliferating cells. mTORC1 increases the ATF4-dependent expression of MTHFD2, a key component of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle that provides one-carbon units for purine synthesis (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016). Additionally, S6K1 phosphorylates and activates carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (CAD), a critical component of the de novo pyrimidine synthesis pathway (Ben-Sahra et al., 2013; Robataille et al., 2013).

mTORC1 also facilitates growth by promoting a shift in glucose metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, which likely facilitates the incorporation of nutrients into new biomass. mTORC1 increases the translation of the transcription factor HIF1α (Fig. 2C), which drives the expression of several glycolytic enzymes such as phospho-fructo kinase (PFK) (Duvel et al., 2010). Furthermore, mTORC1-dependent activation of SREBP leads to increased flux through the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which utilizes carbons from glucose to generate NADPH and other intermediary metabolites needed for proliferation and growth.

지질, 핵산, 및 포도당 대사

성장 중인 세포는 새로운 세포막의 형성 및 확장을 위해 충분한 지질이 필요합니다. mTORC1은 스테롤 반응 요소 결합 단백질(SREBP) 전사 인자를 통해 지방산 및 콜레스테롤 생합성에 관여하는 대사 유전자의 발현을 조절함으로써 지질의 신규 합성을 촉진합니다(Porstmann et al., 2008). SREBP는 일반적으로 스테롤 수준이 낮을 때 활성화되지만, mTORC1 신호전달은 S6K1 의존적 메커니즘(Duvel et al., 2010)을 통해 SREBP를 독립적으로 활성화할 수 있으며, 추가 기질인 Lipin1의 인산화도 mTORC1 신호전달이 결여된 상태에서 SREBP를 억제합니다(Peterson et al., 2011).

최근 연구에서 mTORC1은 성장 및 증식 중인 세포에서 DNA 복제와 리보솜 생성에 필요한 뉴클레오티드 합성을 촉진한다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다. mTORC1은 미토콘드리아 테트라하이드로폴산 회로의 핵심 구성 요소인 MTHFD2의 ATF4 의존적 발현을 증가시킵니다. 이 회로는 푸린 합성에 필요한 1탄소 단위를 공급합니다 (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016). 또한 S6K1은 신생 피리미딘 합성 경로의 핵심 구성 요소인 카바모일-인산 합성효소(CAD)를 인산화하고 활성화합니다(Ben-Sahra et al., 2013; Robataille et al., 2013).

mTORC1은 포도당 대사 경로를 산화적 인산화에서 글리코lysis로 전환시켜 영양소의 새로운 생물량으로의 통합을 촉진함으로써 성장을 촉진합니다. mTORC1은 전사 인자 HIF1α의 번역을 증가시키며(Fig. 2C), 이는 포스포-프루토 키나제(PFK)와 같은 여러 글리코lysis 효소의 발현을 촉진합니다(Duvel et al., 2010). 또한 mTORC1에 의존적인 SREBP 활성화는 산화적 펜토스 인산 경로(PPP)를 통한 유동성을 증가시킵니다. 이 경로는 포도당으로부터 탄소를 활용해 NADPH 및 증식 및 성장에 필요한 중간 대사물을 생성합니다.

Regulation of protein turnover

In addition to the various anabolic processes outlined above, mTORC1 also promotes cell growth by suppressing protein catabolism (Fig. 1B), most notably autophagy. An important early step in autophagy is the activation of ULK1, a kinase that forms a complex with ATG13, FIP2000, and ATG101 and drives autophagosome formation. Under nutrient replete conditions, mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1, thereby preventing its activation by AMPK, a key activator or autophagy (Kim et al., 2011). Thus, the relative activity of mTORC1 and AMPK in different cellular contexts largely determines the extent of autophagy induction. mTORC1 also regulates autophagy in part by phosphorylating and inhibiting the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor TFEB, which drives the expression of genes for lysosomal biogenesis and the autophagy machinery (Martina et al., 2012; Roçzniak-Ferguson et al., 2012; Settembre et al., 2012).

The second major pathway responsible for protein turnover is the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), through which proteins are selectively targeted for degradation by the 20S proteasome following covalent modification with ubiquitin. Two recent studies found that acute mTORC1 inhibition rapidly increases proteasome-dependent proteolysis through either a general increase in protein ubiquitylation, or an increased abundance of proteasomal chaperones via inhibition of Erk5 (Fig. 2B, Rousseau et al., 2016, Zhao et al., 2015). However, another study found that genetic hyper-activation of mTORC1 signaling also increases proteasome activity, through elevated expression of proteasome subunits downstream of Nrf1 (Zhang et al., 2014). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that while acute mTORC1 inhibition promotes proteolysis to restore free amino acid pools, prolonged mTORC1 activation also triggers a compensatory increase in protein turnover to balance the increased rate of protein synthesis. Given that the UPS is responsible for the majority of protein degradation in human cells, precisely how mTORC1 regulates this process is an important question going forward.

단백질 대사 조절

위에서 설명한 다양한 동화 과정 외에도, mTORC1은 단백질 이화 작용(그림 1B), 특히 자가포식을 억제하여 세포 성장을 촉진합니다. 자가포식의 중요한 초기 단계는 ATG13, FIP2000 및 ATG101과 복합체를 형성하고 자식 세포 소체 형성을 유도하는 키나아제인 ULK1의 활성화입니다. 영양분이 풍부한 조건에서 mTORC1은 ULK1을 인산화하여, 자가포식의 주요 활성화제인 AMPK에 의한 ULK1의 활성화를 방지합니다 (Kim et al., 2011). 따라서, 다양한 세포 환경에서 mTORC1과 AMPK의 상대적 활성이 자가포식 유도 정도를 크게 결정합니다. mTORC1은 또한 리소좀 생성과 자가포식 기전의 유전자 발현을 유도하는 전사 인자 TFEB를 인산화하고 핵 전좌를 억제함으로써 자가포식을 부분적으로 조절합니다 (Martina et al., 2012; Roçzniak-Ferguson et al., 2012; Settembre et al., 2012).

단백질 회전의 두 번째 주요 경로는 유비퀴틴-프로테아좀 시스템(UPS)으로, 유비퀴틴과의 공액적 변형 후 20S 프로테아좀에 의해 선택적으로 분해 대상으로 표적화됩니다. 최근 두 연구에서 급성 mTORC1 억제가 프로테아좀 의존적 단백질 분해를 급격히 증가시킨다는 것이 발견되었습니다. 이는 단백질 유비퀴틴화 일반적 증가를 통해 또는 Erk5 억제를 통해 프로테아좀 분자 샤페론의 풍부함이 증가함으로써 발생합니다(Fig. 2B, Rousseau et al., 2016, Zhao et al., 2015). 그러나 다른 연구에서는 mTORC1 신호전달의 유전적 과활성화가 Nrf1 하류에서 프로테아좀 서브유닛의 발현 증가를 통해 프로테아좀 활성을 증가시킨다는 결과가 나왔습니다(Zhang et al., 2014). 이 불일치의 한 가지 가능한 설명은 급성 mTORC1 억제가 자유 아미노산 풀을 회복하기 위해 단백질 분해를 촉진하지만, 장기적인 mTORC1 활성화는 증가한 단백질 합성 속도를 균형 잡기 위해 보상적 단백질 회전율을 증가시킨다는 점입니다. 인간 세포에서 단백질 분해의 대부분을 담당하는 UPS가 이 과정에 어떻게 조절되는지는 향후 중요한 연구 주제입니다.

Downstream of mTORC2

While mTORC1 regulates cell growth and metabolism, mTORC2 instead controls proliferation and survival primarily by phosphorylating several members of the AGC (PKA/PKG/PKC) family of protein kinases (Fig. 2D). The first mTORC2 substrate to be identified was PKCα, a regulator of the actin cytoskeleton (Jacinto et al., 2004, Sarbassov et al., 2004). More recently, mTORC2 has also been shown to phosphorylate several other members of the PKC family, including PKCδ (Gan et al., 2012), PKCζ (Li and Gao, 2014), as well as PKCγ and PKCε (Thomanetz et al., 2013), all of which regulate various aspects of cytoskeletal remodeling and cell migration.

The most important role of mTORC2 however is likely the phosphorylation and activation of Akt, a key effector of insulin/PI3K signaling (Sarbassov et al., 2005). Once active, Akt promotes cell survival, proliferation, and growth through the phosphorylation and inhibition of several key substrates including the FoxO1/3a transcription factors, the metabolic regulator GSK3β, and the mTORC1 inhibitor TSC2. However while mTORC2-dependent phosphorylation is required for Akt to phosphorylate some substrates in vivo, such as FoxO1/3a, it is dispensable for the phosphorylation of others including TSC2 (Guertin et al., 2006; Jacinto et. al., 2006). Finally, mTORC2 also phosphorylates and activates SGK1, another AGC-kinase that regulates ion transport as well as cell survival (Garcia-Martinez and Alessi, 2008).

mTORC2 하류

mTORC1이 세포 성장과 대사 과정을 조절하는 반면, mTORC2는 주로 AGC(PKA/PKG/PKC) 단백질 키나제 가족의 여러 구성원을 인산화함으로써 증식과 생존을 조절합니다(그림 2D). mTORC2의 첫 번째 기질로 확인된 것은 액틴 세포 골격의 조절자인 PKCα입니다(Jacinto et al., 2004, Sarbassov et al., 2004). 최근에는 mTORC2가 PKC 가족의 다른 여러 구성원, 즉 PKCδ (Gan et al., 2012), PKCζ (Li and Gao, 2014), PKCγ 및 PKCε (Thomanetz et al., 2013)를 인산화한다는 것이 밝혀졌으며, 이 모든 구성원은 세포 골격 재편성과 세포 이동의 다양한 측면을 조절합니다.

그러나 mTORC2의 가장 중요한 역할은 아마도 인슐린/PI3K 신호전달의 핵심 효과자인 Akt의 인산화 및 활성화일 것입니다 (Sarbassov et al., 2005). 활성화된 Akt는 FoxO1/3a 전사 인자, 대사 조절인자 GSK3β, mTORC1 억제인자 TSC2 등 여러 핵심 기질의 인산화 및 억제를 통해 세포 생존, 증식, 성장 등을 촉진합니다. 그러나 mTORC2에 의존적인 인산화는 Akt가 일부 기질(예: FoxO1/3a)을 인산화하는 데 필수적이지만, TSC2와 같은 다른 기질의 인산화에는 필수적이지 않습니다(Guertin et al., 2006; Jacinto et al., 2006). 마지막으로, mTORC2는 이온 운반 및 세포 생존을 조절하는 또 다른 AGC 키나아제인 SGK1을 인산화하고 활성화합니다 (Garcia-Martinez and Alessi, 2008).

Upstream of mTORC1

The mTORC1-dependent shift towards increased anabolism should only occur in the presence of pro-growth endocrine signals as well as sufficient energy and chemical building blocks for macromolecular synthesis. In mammals, these inputs are largely dependent on diet, such that mTORC1 is activated following feeding to promote growth and energy storage in tissues such as the liver and muscle, but inhibited during fasting conserve limited resources. Here we discuss the cellular pathways upstream of mTORC1 and the mechanisms through which they control mTORC1 activation.

Growth Factors

Studies of rapamycin in the early 1990s revealed that mTORC1 is a downstream mediator of several growth factor and mitogen-dependent signaling pathways, all of which inhibit a key negative regulator of mTORC1 signaling known as the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) complex. TSC is a heterotrimeric complex comprised of TSC1, TSC2, and TBC1D7 (Dibble et al., 2012), and functions as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for the small GTPase Rheb (Inoki et al., 2003; Tee et al., 2003), which directly binds and activates mTORC1 (Long et al., 2005; Sancak et al., 2007). Although Rheb is an essential activator of mTORC1, exactly how it stimulates mTORC1 kinase activity remains unknown.

Numerous growth factor pathways converge on TSC (Fig. 2A, reviewed in Huang and Manning, 2008), including the insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) pathway, which triggers the Akt-dependent multisite phosphorylation of TSC2. This phosphorylation inhibits TSC by dissociating it from the lysosomal membrane, where at least some fraction of cellular Rheb localizes (Menon et al., 2014). Similarly, receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent Ras signaling activates mTORC1 via the MAP Kinase Erk and its effector p90RSK, both of which also phosphorylate and inhibit TSC2. It is unclear however whether these inputs also control the localization of TSC, or rather inhibit its GAP activity through a distinct mechanism. Additional growth factor pathways upstream of TSC include Wnt and the inflammatory cytokine TNFα, both of which activate mTORC1 through the inhibition of TSC1. Precisely how the TSC complex integrates these numerous signals and their relative impact on mTORC1 activity in various contexts however remains an open question.

Energy, oxygen, and DNA damage

mTORC1 also responds to intracellular and environmental stresses that are incompatible with growth such as low ATP levels, hypoxia, or DNA damage. A reduction in cellular energy charge, for example during glucose deprivation, activates the stress responsive metabolic regulator AMPK, which inhibits mTORC1 both indirectly, through phosphorylation and activation of TSC2, as well as directly through the phosphorylation of Raptor (Gwinn et al., 2008; Inoki et al., 2003b; Shaw et al., 2004). Interestingly, glucose deprivation also inhibits mTORC1 in cells lacking AMPK, through inhibition of the Rag GTPases, suggesting that mTORC1 senses glucose through more than one mechanism (Efeyan et al., 2013; Kalender et al., 2010). Similarly, hypoxia inhibits mTORC1 in part through AMPK activation, but also through the induction of REDD1 (Regulated in DNA damage and development 1), which activates TSC (Brugarolas et al., 2004). Finally, the DNA damage-response pathway inhibits mTORC1 through the induction of p53 target genes including the AMPK regulatory subunit (AMPKβ), PTEN, and TSC2 itself, all of which increase TSC activity (Feng et al., 2007).

Amino Acids

In addition to glucose-dependent insulin release, feeding also leads to an increase in serum amino acid levels due to the digestion of dietary proteins. As amino acids are not only essential building blocks of proteins but also sources of energy and carbon for many other metabolic pathways, mTORC1 activation is tightly coupled to diet-induced changes in amino acid concentrations.

A breakthrough in the understanding of amino acid sensing by mTORC1 came with the discovery of the heterodimeric Rag GTPases as components of the mTORC1 pathway (Kim et al., 2008; Sancak et al., 2008). The Rags are obligate heterodimers of RagA or RagB with RagC or RagD, and are tethered to the lysosomal membrane through their association with the pentameric Ragulator complex comprised of MP1, p14, p18, HBXIP and c7ORF59 (Sancak et al., 2010; Bar-Peled et al., 2012). Amino acid stimulation converts the Rags to their active nucleotide-bound state, allowing them to bind Raptor and recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface, where Rheb is also located. This pathway architecture therefore forms an “AND-gate”, whereby mTORC1 signaling is only on when both the Rags and Rheb are activated, explaining why both growth factors and amino acids are required for mTORC1 activation.

Despite these insights, the identities of the direct amino acid sensors upstream of mTORC1 have been elusive until very recently. It is now clear that mTORC1 senses both intra-lysosomal and cytosolic amino acids through distinct mechanisms. Amino acids inside the lysosomal lumen alter the Rag nucleotide state through a mechanism dependent on the lysosomal v-ATPase, which interacts the Ragulator-Rag complex to promote the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity of Ragulator towards RagA/B (Zoncu et al., 2011; Bar-Peled et al., 2012). The lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 interacts with the Rag-Ragulator-v-ATPase complex and is required for arginine to activate mTORC1, making it a promising candidate to be a lysosomal amino acid sensor (Jung et al., 2015; Rebsamen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015).

Cytosolic leucine and arginine signal to mTORC1 through a distinct pathway comprised of the GATOR1 and GATOR2 complexes (Bar-Peled et al., 2013). GATOR1 consists of DEPDC5, Nprl2 and Nprl3, and inhibits mTORC1 signaling by acting as a GAP for RagA/B. The recently identified KICSTOR complex (consisting of Kaptin, ITFG2, c12orf66, and SZT2) tethers GATOR1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for the appropriate control of the mTORC1 pathway by nutrients (Wolfson et al., 2017). GATOR2 by contrast is a pentameric complex comprised of Mios, WDR24, WDR59, Seh1L and Sec13, and is a positive regulator of mTORC1 signaling that interacts with GATOR1 at the lysosomal membrane (Bar-Peled et al., 2013).

An important insight into the mechanism of cytosolic amino acid sensing came with the identification of Sestrin2 as a GATOR2 interacting protein that inhibits mTORC1 signaling under amino acid deprivation (Chantranupong et al., 2014; Parmigiani et al., 2014). Subsequent biochemical and structural analyses established that Sestrin2 is a direct leucine sensor upstream of mTORC1 that binds and inhibits GATOR2 function in the absence of leucine, and dissociates from it upon leucine binding (Saxton et al., 2016a; Wolfson et al., 2016). Furthermore, the affinity of Sestrin2 for leucine determines the sensitivity of mTORC1 signaling to leucine in cultured cells, demonstrating that Sestrin2 is the primary leucine sensor for mTORC1 in this context. It remains to be seen whether and in what tissues leucine concentrations fluctuate within the relevant range to be sensed by Sestrin2 in vivo, as the levels of interstitial or cytosolic leucine are unknown. Interestingly, another recent study found that Sestrin2 is transcriptionally induced upon prolonged amino acid starvation via the stress-responsive transcription factor ATF4 (Ye et al., 2015), suggesting that Sestrin2 functions as both an acute leucine sensor as well as an indirect mediator of prolonged amino acid starvation.

Cytosolic arginine also activates mTORC1 through the GATOR1/2-Rag pathway by directly binding the recently identified arginine sensor CASTOR1 (Cellular Arginine Sensor for mTORC1). Much like Sestrin2, CASTOR1 binds and inhibits GATOR2 in the absence of arginine, and dissociates upon arginine binding to enable the activation of mTORC1 (Chantranupong et al., 2016; Saxton et al., 2016b). Thus, both leucine and arginine stimulate mTORC1 activity at least in part by releasing inhibitors from GATOR2, establishing GATOR2 as a central node in the signaling of amino acids to mTORC1. Importantly however, the molecular function of GATOR2 and the mechanisms through which Sestrin2 and CASTOR1 regulate it are unknown.

Several additional mechanisms through which amino acids regulate mTORC1 signaling have also recently been reported, including the identification of the Folliculin-FNIP2 complex as a GAP for RagC/D that activates mTORC1 in the presence of amino acids (Petit et al., 2013; Tsun et al., 2013). Another study found that the amino acid glutamine, which is utilized as a nitrogen and energy source by proliferating cells, activates mTORC1 independently of the Rag GTPases through the related Arf family GTPases (Jewell et al., 2015). Finally, a recent report found that the small polypeptide SPAR associates with the v-ATPase-Ragulator complex to suppress mTORC1 recruitment to lysosomes, though how this occurs is unclear (Matsumoto et al., 2016).

Upstream of mTORC2

In contrast to mTORC1, mTORC2 primarily functions as an effector of insulin/PI3K signaling (Fig. 2A). Like most PI3K regulated proteins, the mTORC2 subunit mSin1 contains a phosphoinositide-binding PH domain that is critical for the insulin-dependent regulation of mTORC2 activity. The mSin1 PH domain inhibits mTORC2 catalytic activity in the absence of insulin, and this autoinhibition is relieved upon binding to PI3K-generated PIP3 at the plasma membrane (Liu et al., 2015). mSin1 can also be phosphorylated by Akt, suggesting the existence of a positive-feedback loop whereby partial activation of Akt promotes the activation of mTORC2, which in turn phosphorylates and fully activates Akt (Yang et al., 2015). Another study found that PI3K promotes the association of mTORC2 with ribosomes to activate its kinase activity, although the mechanistic basis for this is unclear (Zinzalla et al., 2011).

Unexpectedly, mTORC2 signaling is also regulated by mTORC1, due to the presence of a negative feedback loop between mTORC1 and insulin/PI3K signaling. mTORC1 phosphorylates and activates Grb10, a negative regulator of insulin/IGF-1 receptor signaling upstream of Akt and mTORC2, (Hsu et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011), while S6K1 also suppresses mTORC2 activation through the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) (Harrington et al., 2004; Shah et al., 2004). This negative feedback regulation of PI3K and mTORC2 signaling by mTORC1 has numerous implications for the pharmacological targeting of mTOR in disease, discussed below.

Evolutionary conservation of the TOR pathway

One remarkable feature of the TOR pathway is its conservation as a major growth regulator in virtually all eukaryotes. Like mammals, S. cerevisiae also have two distinct TOR containing complexes, TORC1 and TORC2 (reviewed in Loewith and Hall, 2011) as well as homologs of Raptor (Kog1), mLST8 (Lst8), Rictor (Avo3), and mSin1 (Avo1), although several additional components are yeast or mammal specific. Furthermore yeast TORC1 also primarily controls cell growth and anabolic metabolism, including the activation of protein synthesis and inhibition of autophagy, while yeast TORC2 primarily functions to activate AGC family kinases such as YPK1, the homologue of mammalian SGK1.

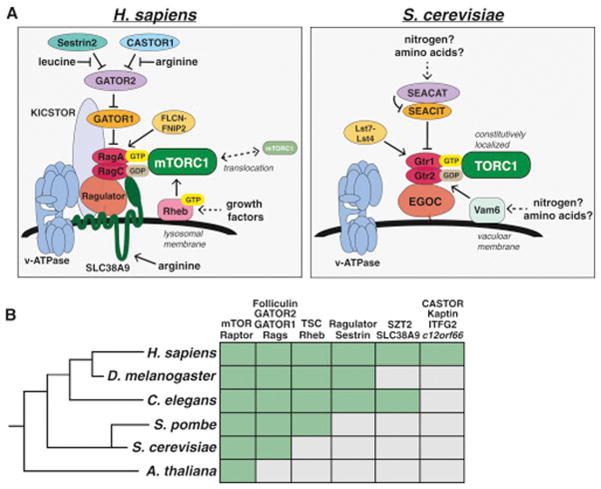

As with mTORC1, yeast TORC1 also senses and responds to a diverse array of environmental stimuli, although the specific inputs and upstream signaling components differ in several respects, as one would expect given the vastly different environmental conditions that are relevant for these organisms (Fig. 3A). For example, hormone and growth factor receptor signaling are developments specific to multicellular organisms, and the mTORC1 regulator TSC is not found in S. cerevisiae. Instead, yeast TORC1 appears to be primarily sensitive to direct biosynthetic inputs such as carbon, nitrogen and phosphate sources.

Figure 3. Evolutionary Conservation of the mTOR Pathway.

(A) The nutrient sensing pathway upstream of mammalian mTORC1 (left) and yeast TORC1 (right).

(B) Phylogenetic tree depicting the presence (green box) of key mTORC1 regulators in various model organisms.

Unlike mammals, yeast are able to synthesize all 20 amino acids, and starvation of individual amino acids like leucine or arginine does not inhibit TORC1 signaling in wild-type strains. Leucine deprivation does inhibit TORC1 in leucine-auxotrophs however (Binda et al., 2009), suggesting there may be a mechanism for signaling amino acid levels to TORC1, although this could also be due to the sensing of nitrogen sources that are perturbed in this context. Both the Rag GTPases and the GATOR1/2 complexes are present in S. cerevisiae in the form of Gtr1/2 and the SEACIT/SEACAT complexes, respectively (Fig. 3A, Panchaud et al., 2009), while the yeast EGO Complex is a structural homolog of Ragulator that interacts with Gtr1/2 and likely serves an analogous function (Powis et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012). In contrast to mammals however, amino acids do not affect the localization of yeast TORC1, which is constitutively bound to the Gtr-Ego complex at the vacuolar membrane (Binda et al., 2009), suggesting an alternative sensing mechanism exists. Consistent with this, the mammalian amino acid sensors SLC38A9, Sestrin2, and CASTOR1 all lack clear homologs in yeast.

While most of the TORC1 pathway components are also well conserved in other multicellular model organisms, the direct amino acid sensors appear to have diverged (Fig. 3B). For example, although both SLC38A9 and CASTOR1 are conserved throughout many metazoan lineages, they are absent in D. melanogaster, suggesting that this organism either does not sense arginine or does so through a distinct mechanism. Both D. melanogaster and C. elegans do have a Sestrin homolog however, and dmSestrin also binds leucine (Wolfson et al., 2016). Interestingly, both ceSestrin and dmSestrin contain subtle differences in their leucine binding pockets predicted to reduce their affinity for leucine relative to human Sestrin2, likely enabling the sensing of physiologically relevant leucine levels in these organisms (Saxton et al., 2016a).

Physiological roles of mTOR

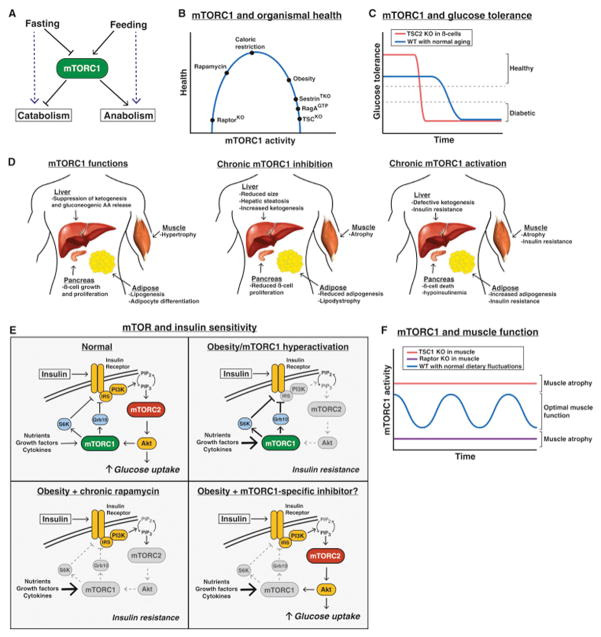

Changes in available energy sources following fasting or feeding require alterations in whole body metabolism to maintain homeostasis. Under starvation, levels of nutrients and growth factors drop, inducing a catabolic state in which energy stores are mobilized to maintain essential functions (Fig. 4A). Alternatively, high levels of nutrients in the fed-state trigger a switch towards anabolic growth and energy storage. Consistent with its role in coordinating anabolic and catabolic metabolism at the cellular level, physiological studies in mice have revealed that mTOR signaling is essential for proper metabolic regulation at the organismal level as well. Importantly, however, constitutive mTOR activation is also associated with negative physiological outcomes, indicating that the proper modulation of mTOR signaling in response to changing environmental conditions is crucial (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Physiological Roles of mTOR.

(A) mTORC1 controls the balance between anabolism and catabolism in response to fasting and feeding.

(B) The effect of cumulative mTORC1 activity on overall health.

(C) The effect of mTORC1 hyperactivation in pancreatic β-cells on glucose tolerance over time.

(D) The normal functions of mTORC1 in the liver, muscle, pancreas, and adipose tissue (left), and the consequences of chronic mTORC1 inhibition (middle) or activation (right).

(E) Deregulation of mTORC1 signaling in insulin resistance/diabetes, and the effect of rapamycin or a theoretical mTORC1 specific inhibitor.

Glucose homeostasis

When blood glucose levels drop, the liver activates a compensatory response involving the induction of autophagy, gluconeogenesis, and the release of alternative energy sources in the form of ketone bodies. Several lines of evidence suggest that regulation of mTORC1 signaling is crucial for the response of the liver to diet. For example, mice with liver specific deletion of TSC1, which have constitutively activated mTORC1 signaling, fail to generate ketone bodies during fasting due to sustained mTORC1-dependent suppression of PPARa, a transcriptional activator of ketogenic genes (Sengupta et al., 2010). The importance of inhibiting mTORC1 in the liver during fasting has also been observed through the generation mice with a while-body knock-in of a constitutively active allele of RagA (RagAGTP). Although they develop normally, these mice die rapidly after birth due to an inability to maintain blood glucose levels during the perinatal fasting period (Efeyan et al., 2013). Further analysis of these mice revealed that sustained mTORC1 activity during this fasting period prevents the induction of autophagy in the liver, which is critical for supplying free amino acids for gluconeogenesis. As a result, RagAGTP mice display fatal hypoglycemia in response to fasting, consistent with a similar phenotype in autophagy deficient mice (Kuma et al., 2004).

mTORC1 signaling also plays an important role in glucose homeostasis by regulating pancreatic β-cell function. Studies using β-cell specific TSC2 knock out (β-TSC2KO) mice revealed that hyperactivation of mTORC1 has a biphasic effect on β-cell function, with young β-TSC2KO mice exhibiting increased β-cell mass, higher insulin levels, and improved glucose tolerance (Mori et al., 2009; Shigeyama et al., 2008). This effect is reversed in older β-TSC2KO mice, which more rapidly develop reduced β-cell mass, lower insulin levels, and hyperglycemia. Thus, high mTORC1 activity in the pancreas is initially beneficial for glucose tolerance, but also leads to a faster decline in β-cell function over time (Fig. 4C).

This biphasic effect of mTORC1 signaling is reminiscent of diet-induced (type 2) diabetes progression, in which pancreatic β-cells initially expand and produce more insulin to compensate for an increased glycemic load, but eventually undergo exhaustion. Indeed, obese or high fat diet (HFD) treated mice have high mTORC1 signaling in many tissues, including the pancreas, likely due to increased levels of circulating insulin, amino acids, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Khamzina et al., 2005). Increased mTORC1 signaling in these tissues also contributes to peripheral insulin resistance due to enhanced feedback inhibition of insulin/PI3K/Akt signaling, which is prevented in mice lacking S6K1/2 (Fig. 4D, Um et al., 2004).

That mTORC1 hyperactivation from genetic or dietary manipulation results in insulin resistance has led many to speculate that mTORC1 inhibitors could improve glucose tolerance and protect against type 2 diabetes. Paradoxically, however, chronic pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 using rapamycin has the opposite effect, causing insulin resistance and impaired glucose homeostasis (Fig. 4D, Cunningham et al., 2007). This result is explained at least in part by the fact that prolonged rapamycin treatment also inhibits mTORC2 signaling in vivo (Lamming et al., 2012). As mTORC2 directly activates Akt downstream of insulin/PI3K signaling, it is not surprising that mTORC2 inhibition disrupts the physiological response to insulin. Consistent with this, liver specific Rictor knockout mice have severe insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (Hagiwara et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2012), as do mice lacking Rictor in the muscle or fat (Kumar et al., 2008 & 2010).

Muscle mass and function

Although the importance of mTOR signaling in promoting muscle growth is well appreciated by basic scientists and bodybuilders alike, the mechanisms underlying this process are still poorly understood, in part due to the difficulty of genetically manipulating multinucleate myocytes in vivo. Nonetheless, early studies of mTOR signaling in the muscle revealed that mTORC1 activation is associated with muscle hypertrophy (Bodine et al., 2001) and that both IGF-1 and leucine promote hypertrophy through the activation of mTORC1 signaling in cultured cells and in mice (Anthony et al., 2000; Rommel et al., 2001). Moreover, muscle specific Raptor knockout mice display severe muscle atrophy and reduced body weight leading to early death (Bentzinger et al., 2008). This dramatic phenotype is also observed in muscle specific mTOR knockout mice, but not Rictor deficient mice, suggesting that the critical functions of mTOR in skeletal muscle are through mTORC1 (Bentzinger et al., 2008; Risson et al., 2009).

While acute activation of mTORC1 signaling in vivo does promote muscle hypertrophy in the short-term (Bodine et al., 2001) chronic mTORC1 activation in the muscle through loss of TSC1 also results in severe muscle atrophy, low body mass, and early death, primarily due to a lack the inability to induce autophagy in this tissue (Fig. 4D, Castets et al, 2013). Considering that turnover of old or damaged tissue plays a critical role in muscle growth, these results suggest that alternating periods of high and low mTORC1 activity, as occurs with normal feeding and fasting cycles, is essential for maintaining optimal muscle health and function (Fig. 4F).

An accumulating body of evidence suggests that muscle contraction also activates mTORC1 in the muscle; potentially explaining at least in part how increased muscle use promotes anabolism (Baar and Esser, 1999). A recent study found that mechanical stimuli activate mTORC1 signaling by inducing the phosphorylation of Raptor (Frey et al., 2014), although how this occurs in not clear. Understanding how mTORC1 can integrate the distinct signals from insulin, amino acids, and mechanical force in the muscle will be an important goal going forward and may inform approaches for treating muscle wasting disorders such as those associated with disuse and aging.

Adipogenesis and lipid homeostasis

Many studies over the last two decades also reveal a role for mTOR in promoting adipocyte formation and lipid synthesis in response to feeding and insulin (Fig. 4D, reviewed in Lamming and Sabatini, 2013). mTORC1 promotes adipogenesis and enhanced lipogenesis in cell culture and in vivo, consistent with adipocyte-specific raptor knock out (Ad-RapKO) mice displaying lipodystrophy and hepatic steatosis (Lee et al., 2016). However, the role of mTORC1 in adipose is complicated by the fact that Ad-RapKO mice are also resistant to diet induced obesity due to reduced adipogenesis, suggesting mTORC1 inhibition in this tissue can have both positive and negative effects (Polak et al., 2008).

Similarly, the loss of mTORC2 activity in adipocytes primarily results in insulin resistance due to reduced Akt activity (Kumar et al., 2010), but also in less lipid synthesis in part due to reduced expression of ChREBPβ, a master transcription factor for lipogenic genes (Tang et al., 2016). mTORC2 has also been shown to promote lipogenesis in the liver as well, suggesting a general role for mTORC2 in lipid synthesis (Hagiwara et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2012) Thus, both mTORC1 and mTORC2 play important roles in multiple aspects of adipocyte function and lipid metabolism.

Immune function

Early studies into the biological properties of rapamycin revealed a role in blocking lymphocyte proliferation, leading to its eventual clinical approval as an immunosuppressant for kidney transplants in 1999. The immunosuppressive action of rapamycin is largely attributed to its ability to block T-cell activation, a key aspect of the adaptive immune response (reviewed in Powell et al., 2012). Mechanistically, mTORC1 facilitates the switch towards anabolic metabolism that is required for T-cell activation and expansion, and lies downstream of several activating signals present in the immune microenvironment including IL-2, the co-stimulatory receptor CD28, as well as amino acids. Interestingly, mTORC1 inhibition during antigen presentation results in T-cell anergy, whereby cells fail to activate upon subsequent antigen exposure (Zheng et al., 2007). As the induction of T-cell anergy via nutrient depletion or other inhibitory signals is a mechanism utilized by tumors in immune evasion, these data suggest that promoting mTORC1 activation in immune cells may actually be beneficial in some contexts, such as cancer immunotherapy.

Recent studies have also found a role for mTORC1 in influencing T-cell maturation, as rapamycin promotes the differentiation and expansion of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T-cells and CD8+ memory T-cells while suppressing CD8+ and CD4+ effector T-cell populations (Araki et al., 2009; Haxhanisto et al., 2008), consistent with the metabolic profiles of these cell types. Indeed, a recent report found that during the asymmetric division of activated CD8+ T-cells, high mTORC1 activity is high in the “effector-like” daughter cell, but low in the “memory-like” daughter cell, due to the asymmetric partitioning of amino acid transporters (Polizzi et al., 2016; Verbist et al., 2016). Thus, the role of mTOR signaling in the immune system is clearly more complex than previously thought. Given the current clinical use of mTOR inhibitors in both immunosuppression and cancer, a more comprehensive understanding of how mTOR signaling influences overall immune responses in vivo will be a critical goal going forward.

Brain function

mTOR has also emerged as an important regulator of numerous neurological processes including neural development, circuit formation, and the neural control of feeding (reviewed in Lipton and Sahin, 2014). The deletion of either Raptor or Rictor in neurons causes reduced neuron size, and early death, suggesting that signaling by both mTORC1 and mTORC2 is important for proper brain development. Conversely, the impact of hyperactive mTORC1 signaling in the brain is best observed in human patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), who exhibit a range of debilitating neurological disorders including epilepsy, autism, and the presence of benign brain tumors.

The fact that mTORC1 hyperactivation in TSC patients correlates with a high occurrence of epileptic seizures (90% of TSC patients) and autistic traits (50%) suggests that deregulated mTORC1 signaling may also be involved in epilepsy and autism more generally. Indeed, mTORC1 hyperactivation in mice through neural loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 leads to severe epileptic seizures that are prevented by rapamycin treatment (Zeng et al., 2008), and mutations in components of the GATOR1 and KICSTOR complexes have been linked to epilepsy in humans (Basel-Vanagaite et al., 2013; Ricos et al., 2016).

The importance of mTORC1 in this tissue stems in part from its role in promoting activity-dependent mRNA translation near synapses, a critical step in neuronal circuit formation. Consistent with this, the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine acutely activates mTORC1 signaling in mouse neurons, which coincides with an increased translation of synaptic proteins (Li et al., 2010). The role of mTORC1 in regulating autophagy is likely also important, as autophagy dysfunction is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Inhibiting mTOR signaling has beneficial effects on mouse models of AD (Spilman et al., 2010), and it remains to be seen whether similar results will be seen in humans.

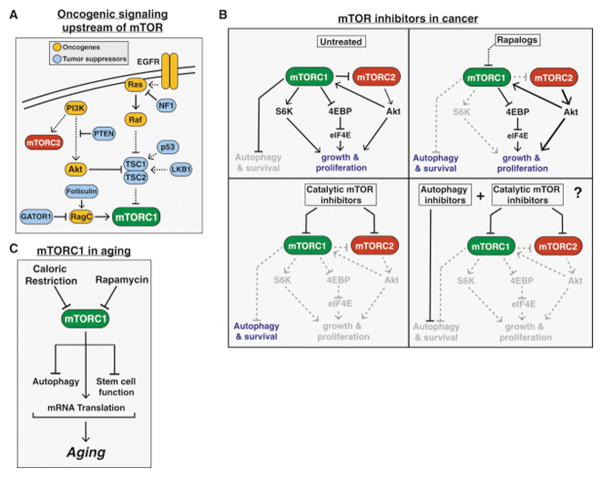

mTOR in Cancer

As discussed above, mTORC1 functions as a downstream effector for many frequently mutated oncogenic pathways including the PI3K/Akt pathway as well as the Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk (MAPK) pathway, resulting in mTORC1 hyperactivation in a high percentage of human cancers (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the common tumor suppressors TP53 and LKB1 are negative regulators of mTORC1 upstream of TSC1 and TSC2, which are also tumor suppressors originally identified through genetic analysis of the familial cancer syndrome TSC. Several components of the nutrient sensing input to mTORC1 have also been implicated in cancer progression, including all three subunits of the GATOR1 complex, which are mutated with low frequency in glioblastoma (Bar-Peled et al., 2013), as well as RagC, which was recently found to be mutated at high frequency (~18%) in follicular lymphoma (Okosun et al., 2015). Additionally, mutations in the gene encoding folliculin (FLCN) are the causative lesion in the Birt-Hogg-Dube hereditary cancer syndrome (Nickerson et al., 2002), which manifests similarly to TSC. Finally, mutations in MTOR itself are also found in a variety of cancer subtypes, consistent with a role for mTOR in tumorigenesis (Grabiner et al., 2014; Sato et al., 2010).

Figure 5. mTOR in Cancer and Aging.

(A) The common tumor suppressors and oncogenes upstream of mTORC1 leading to increased mTORC1 signaling in a wide variety of cancers.

(B) The varying effects of rapalogs, catalytic mTOR inhibitors, a combination of an mTOR inhibitor and autophagy inhibitor on cancer proliferation and survival.

(C) The role of mTORC1 signaling in aging.

mTORC2 signaling is also implicated in cancer largely due to its role in activating Akt, which drives pro-proliferative processes such as glucose uptake and glycolysis while also inhibiting apoptosis. Indeed, at least some PI3K/Akt driven tumors appear to rely on mTORC2 activity, as Rictor is essential in mouse models of prostate cancer driven by PTEN loss, as well as in human prostate cancer cell lines that lack PTEN (Guertin et al., 2009; Hietakangas et al., 2008).

While many mTORC1-driven processes likely contribute to tumorigenesis, the translational program initiated by the phosphorylation of 4EBP is likely the most critical, at least in mouse models of Akt-driven prostate cancer and T-cell lymphoma (Hsieh et al., 2010 & 2012). Consistent with this, a variety of Akt and Erk driven cancer cell lines are dependent on 4EBP phosphorylation, and the ratio of 4EBP to eIF4E expression correlates well with their sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors (Alain et al., 2012; She et al., 2010).

The first mTOR inhibitors approved for use in cancer were a class of rapamycin derivatives known as “rapalogs”. The rapalog temsirolimus (Pfizer) was first approved for treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma in 2007, followed by everolimus (Novartis) in 2009. Although a small number of “extraordinary responders” have been reported, these rapalogs have been less successful in the clinic than anticipated from pre-clinical cancer models.

Several explanations for this lack of efficacy have been suggested. The first came with the realization that, as allosteric inhibitors, the rapalogs block the phosphorylation of some but not all mTORC1 substrates (Fig. 5B, Choo et al., 2008; Feldman et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2013; Thoreen et al., 2009). In particular, the phosphorylation of 4EBP is largely insensitive to rapamycin. Second, inhibiting mTORC1 releases the negative feedback on insulin/PI3K/Akt signaling, and therefore may paradoxically promote cell survival and prevent apoptosis in some contexts. Indeed, increased Akt signaling has been observed in biopsies of cancer patients following everolimus treatment, and may help explain why rapalogs have largely cytostatic, but not cytotoxic, effects on tumors (Tabernero et al., 2008). Finally, mTORC1 inhibition also induces autophagy, which can help maintain cancer cell survival poorly vascularized, nutrient poor microenvironments such as in pancreatic tumors. Indeed, mTORC1 inhibition also promotes macropinocytosis, whereby extracellular proteins are internalized and degraded to provide amino acids for nutrient-starved tumors (Palm et al., 2015). These data suggest that combining rapalogs with autophagy inhibitors may improve efficacy, consistent with a recent phase 1 clinical trial using temsirolomus and the autophagy inhibitor hydrochloroquine in melanoma patients, which showed an improvement over temsirolomus alone (Rangwala et al., 2014).

In order to address some of the drawbacks of the rapalogs, “second generation,” ATP-competitive catalytic inhibitors against mTOR have also been developed and are now in clinical trials. Unlike rapamycin, these compounds directly inhibit the catalytic activity of mTOR and therefore fully suppress both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Fig. 5B), making them more effective than rapalogs in a variety of preclinical cancer models. Although these second-generation mTOR inhibitors initially suppress Akt signaling due to inhibition of mTORC2, the release of negative feedback on Insulin/PI3K signaling eventually overcomes this blockade and Akt is reactivated following long-term treatment (Rodrik-Outmezguine et al., 2011). One possible solution to this problem may be the utilization of dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors, which inhibit the closely related catalytic domains of both PI3K and mTOR, thereby more fully blocking phosphorylation of both Akt and 4EBP (Fig. 5B). These inhibitors have also shown some promise in preclinical and early clinical trial data, but have raised concerns over dose-limiting toxicities.

The cases where rapalogs have had the most success to date have generally involved mutations in the mTOR pathway itself, such as in TSC1 or MTOR (Iyer et al., 2012; Wagle et al., 2014a). Even in these cases, however, an exquisite initial response has been followed by additional mutations in the kinase or FRB domains of MTOR, leading to acquired resistance (Wagle et al., 2014b). One creative way to overcome these resistance mutations may be with the recently described “third-generation” mTOR inhibitor called “RapaLink,” in which the ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitor is chemically linked to rapamycin, enabling inhibition of mTOR mutants that are resistant to either MLN0128 or rapamycin alone (Rodrik-Outmezguine et al., 2016).

mTOR in Aging

mTOR signaling is strongly implicated in the aging process of diverse organisms including yeast, worms, flies, and mammals. This was first observed through studies in the nematode C. elegans, which found that reduced expression of the homologs of mTOR (ceTOR, formerly let-363) or Raptor (daf-15) extend life span (Vellai et al., 2003; Jia et al., 2004). Subsequent genetic studies found that reduced TOR signaling also promotes longevity in Drosophila (Kapahi et al., 2004), budding yeast, (Kaeberlin et al., 2005) as well as mice (Lamming et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013). Consistent with this, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is currently the only pharmacological treatment proven to extend life span in all of these model organisms (Bjedov et al., 2010; Harrison et al., 2009; Powers et al., 2006; Robida-Stubbs et al., 2012).

The only other intervention shown to extend lifespan in such a wide range of organisms is caloric restriction (CR), defined as a reduction in nutrient intake without malnutrition. Given the critical role of mTORC1 in sensing nutrients and insulin, this has led many to speculate that the beneficial effects of CR on life span are also due to reduced mTORC1 signaling. Indeed, CR-like regimens do not further extend life span in yeast, worms, or flies with reduced mTOR signaling, suggesting an overlapping mechanism (Kaeberlin et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2007; Kapahi et al., 2004).

While there is now a general consensus that mTOR signaling plays a key role in mammalian aging, the mechanism through which this occurs is still unclear. Several lines of evidence suggest that the general reduction in mRNA translation during mTORC1 inhibition slows aging by reducing the accumulation of proteotoxic and oxidative stress, consistent with the observation that loss of the mTORC1 substrate S6K1 also extends life span in mammals (Selman et al., 2009). A related possibility is that inhibition of mTORC1 slows aging by increasing autophagy, which helps clear damaged proteins and organelles such as mitochondria, the accumulation of which are also associated with aging and aging-related diseases. Finally, another model suggests that the attenuation of adult stem cells in various tissues plays a central role in organismal aging, and mTOR inhibition boosts the self-renewal capacity of both hematopoietic and intestinal stem cells in mice (Chen et al., 2009; Yilmaz et al., 2012). Ultimately, the importance of mTORC1 signaling in aging likely reflects its unique capacity to regulate such a wide variety of key cellular functions (Fig 5C).

The observation that mTOR inhibition extends life span and delays the onset of age-associated diseases in mammals has led many to speculate that mTOR inhibitors could be used to enhance longevity in humans. The major drawback of prolonged rapamycin treatment in humans however is the potential for side effects such as immunosuppression and glucose intolerance. There is reason for optimism however, as a trial in healthy elderly humans using everolimus showed safety and even improved immune function (Mannick et al., 2014), and alternative dosing regimens have been proposed that can promote longevity with reduced side effects (Arriola Apelo et al., 2016). Given that many of the negative metabolic side effects associated with mTOR inhibitors are due to inhibition of mTORC2, while the anti-aging effects are due to inhibition of mTORC1, the development of mTORC1 specific inhibitors would be particularly beneficial.

Perspectives

It is now clear that the mTOR pathway plays a central role in sensing environmental conditions and regulating nearly all aspects metabolism at both the cellular and organismal level. In just the last several years, many new insights into both mTOR function and regulation have been elucidated, and extensive genetic and pharmacological studies in mice have enhanced our understanding of how mTOR dysfunction contributes to disease.

While many inputs to mTORC1 have now been identified and their mechanisms of sensing characterized, an integrated understanding of the relative importance of these signals and the contexts in which they are important remains largely unclear. For example, it remains mysterious which inputs to the TSC complex are dominant and how this depends on the physiological context. Similar questions exist for nutrient sensing by the Rag GTPases, specifically regarding the purpose of sensing of both lysosomal and cytosolic amino acids, as well as the tissues in which the nutrient sensors such as Sestrin2, CASTOR1, and SLC38A9 are most important. Such insights will likely require both deeper biochemical studies of these complexes in vitro as well as improved mouse models that enable more nuanced perturbation and monitoring of these sensors in vivo.

The major focus of mTOR research going forward however will be to address whether these molecular insights can improve the therapeutic targeting of mTOR in the clinic. Although rapalogs and catalytic mTOR inhibitors have been successful in the context of immunosuppression and a small subset of cancer types, clear limitations have arisen which limit their utility. Specifically, given the critical functions of mTOR in most human tissues, complete catalytic inhibition causes severe dose-limiting toxicities, while rapalogs also suffer from the drawbacks associated with lack of tissue specificity and unwanted disruption of mTORC2. Future work should focus on the development of mTOR-targeting therapeutics outside of these two modalities, such as truly mTORC1-specific inhibitors for use in diabetes, neurodegeneration, and life-span extension, or tissue-specific mTORC1 agonists for use in muscle wasting diseases and immunotherapy. Such approaches will likely require going beyond targeting mTOR directly to instead developing compounds that modulate tissue-specific receptors or signaling molecules upstream of mTOR, such as the recently characterized amino acid sensors Sestrin2 and CASTOR1, which contain small-molecule binding pockets and specifically regulate mTORC1. Ultimately, such insights may enable the rational targeting of mTOR signaling to unlock the full therapeutic potential of this remarkable pathway.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alain T, Morita M, Fonseca BD, Yanagiya A, Siddiqui N, Bhat M, Zammit D, Marcus V, Metrakos P, Voyer LA, et al. eIF4E/4E-BP ratio predicts the efficacy of mTOR targeted therapies. Cancer research. 2012;72:6468–6476. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Yoshizawa F, Anthony TG, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. The Journal of nutrition. 2000;130:2413–2419. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K, Turner AP, Shaffer VO, Gangappa S, Keller SA, Bachmann MF, Larsen CP, Ahmed R. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriola Apelo SI, Neuman JC, Baar EL, Syed FA, Cummings NE, Brar HK, Pumper CP, Kimple ME, Lamming DW. Alternative rapamycin treatment regimens mitigate the impact of rapamycin on glucose homeostasis and the immune system. Aging cell. 2016;15:28–38. doi: 10.1111/acel.12405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylett CH, Sauer E, Imseng S, Boehringer D, Hall MN, Ban N, Maier T. Architecture of human mTOR complex 1. Science. 2016;351:48–52. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baar K, Esser K. Phosphorylation of p70(S6k) correlates with increased skeletal muscle mass following resistance exercise. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:C120–127. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM. A Tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2013;340:1100–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1232044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell. 2012;150:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baretic D, Berndt A, Ohashi Y, Johnson CM, Williams RL. Tor forms a dimer through an N-terminal helical solenoid with a complex topology. Nature communications. 2016;7:11016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basel-Vanagaite L, Hershkovitz T, Heyman E, Raspall-Chaure M, Kakar N, Smirin-Yosef P, Vila-Pueyo M, Kornreich L, Thiele H, Bode H, et al. Biallelic SZT2 mutations cause infantile encephalopathy with epilepsy and dysmorphic corpus callosum. American journal of human genetics. 2013;93:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]