꼭 알아야 할 지식

1. 필수 아미노산은 단백질 형태로 외부에서 섭취해야 하므로

분지사슬 아미노산처럼 먹으면 어떤 이익이 있는가? 많이 먹으면 어떤 손해가 있는가? 이 관점의 탐구가 필요

2. 비필수 아미노산은 인체 대사과정에서 만들어기 때문에

아미노산 대사과정에서 오류가 생길때 어떤 질병이 발생하고 악화되는가? 이 관점의 탐구가 필요

필수 아미노산 : HILL MPTTV

비필수 아미노산 : aaa cggg pst

Cancers (Basel)

. 2019 May 15;11(5):675. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050675

The Diverse Functions of Non-Essential Amino Acids in Cancer

Bo-Hyun Choi 1, Jonathan L Coloff 1,*

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC6562791 PMID: 31096630

Abstract

Far beyond simply being 11 of the 20 amino acids needed for protein synthesis, non-essential amino acids play numerous important roles in tumor metabolism. These diverse functions include providing precursors for the biosynthesis of macromolecules, controlling redox status and antioxidant systems, and serving as substrates for post-translational and epigenetic modifications. This functional diversity has sparked great interest in targeting non-essential amino acid metabolism for cancer therapy and has motivated the development of several therapies that are either already used in the clinic or are currently in clinical trials. In this review, we will discuss the important roles that each of the 11 non-essential amino acids play in cancer, how their metabolic pathways are linked, and how researchers are working to overcome the unique challenges of targeting non-essential amino acid metabolism for cancer therapy.

초록

비필수 아미노산은

단순히 단백질 합성에 필요한 20가지 아미노산 중 11가지에 불과한 것을 넘어,

종양 대사에서 다양한 중요한 역할을 수행합니다.

이러한 다양한 기능에는

대분자 생합성의 전구체 제공,

환원 상태 및 항산화 시스템 조절,

후전사적 및 에피게놈적 변형의 기질 역할 등이 포함됩니다.

precursors for the biosynthesis of macromolecules,

controlling redox status and antioxidant systems, and

serving as substrates for post-translational and epigenetic modifications

이 기능적 다양성은

암 치료를 위해 비필수 아미노산 대사 경로를 표적으로 삼는 연구에 큰 관심을 불러일으켰으며,

이미 임상에서 사용 중이거나 현재 임상 시험 중인 여러 치료법의 개발을 촉진했습니다.

이 리뷰에서는

11가지 비필수 아미노산 각각이 암에서 수행하는 중요한 역할,

그들의 대사 경로가 어떻게 연결되어 있는지,

그리고 연구자들이 암 치료를 위해

비필수 아미노산 대사 경로를 표적으로 삼는 데 직면한

독특한 도전 과제를 극복하기 위해 어떻게 노력하고 있는지 논의할 것입니다.

Keywords: aspartate, asparagine, arginine, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, cancer

1. Introduction

It is now well established that tumors display different metabolic phenotypes than normal tissues [1]. The first observed and most studied metabolic phenotype of tumors is that of increased glucose uptake and glycolysis [2,3], a metabolic phenotype that is exploited in the clinic to image human tumors and metastases via 18flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) [4]. In addition to glucose, there has also been a long-standing interest in understanding the unique amino acid requirements of cancer cells [5]. Indeed, like glucose, there are major differences in the uptake and secretion of several amino acids in tumors relative to normal tissues [5,6,7]. Further, it is now appreciated that amino acids, rather than glucose, account for the majority of the carbon-based biomass production in rapidly proliferating cancer cells [8]. Amino acids also contain nitrogen and have been demonstrated to be the dominant nitrogen source for hexosamines, nucleotides, and other nitrogenous compounds in rapidly proliferating cells [9,10,11]. Because of these important roles in tumor metabolism, there continues to be significant interest in targeting amino acid metabolism for cancer therapy.

1. 서론

종양은

정상 조직과 다른 대사적 특성을 나타낸다는 것은

이제 널리 인정되고 있습니다 [1].

종양에서 처음 관찰되고 가장 많이 연구된 대사적 특성은

이 대사적 특성은 1

8플루오로데옥시글루코스 양전자 방출 단층 촬영(18FDG-PET)을 통해

인간 종양과 전이를 영상화하는 데 임상적으로 활용되고 있습니다 [4].

포도당 외에도

암 세포의 독특한 아미노산 요구 사항을 이해하는 데

오랜 관심이 기울여져 왔습니다 [5].

실제로 포도당과 마찬가지로,

종양과 정상 조직 사이에서

여러 아미노산의 흡수 및 분비에 큰 차이가 존재합니다 [5,6,7].

또한,

빠르게 증식하는 암 세포에서 탄소 기반 생물량 생산의 대부분은

포도당이 아닌 아미노산에 의해 이루어진다는 점이 이제 인정되고 있습니다 [8].

hexosamines, nucleotides, and other nitrogenous compounds in rapidly proliferating cells

아미노산은 질소를 함유하며,

빠르게 증식하는 세포에서 헥소사민, 뉴클레오티드 및 기타 질소 함유 화합물의 주요 질소 공급원으로

이러한 종양 대사에서의 중요한 역할로 인해

아미노산 대사 표적 치료에 대한

관심이 지속되고 있습니다.

The 20 proteinogenic amino acids can be divided into two primary subgroups—essential amino acids (EAAs) and non-essential amino acids (NEAAs) [12]. This classification is based on dietary necessity, and an amino acid is deemed essential if it “…cannot be synthesized by the animal organism, out of materials ordinarily available to the cells, at a speed commensurate with the demands for normal growth [13].” In humans there are 9 essential amino acids (histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine) and 11 non-essential amino acids (alanine, aspartate, asparagine, arginine, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine). Of the 11 NEAAs, at least 6 are considered “conditionally essential” because there are physiological and/or pathological conditions where they become dietarily required, such as in the inborn error of metabolism phenylketonuria where tyrosine can no longer be synthesized and therefore needs to be consumed [14]. It is important to note that the dietary essentiality of amino acids is considered at the organismal level, as it is known that certain cell types and tissues lack the ability to synthesize or take up some NEAAs. In addition, the circulating concentrations of the 11 NEAAs in humans are highly variable, ranging from 20 µM for aspartate to 550 µM for glutamine [15]. Further, it has been observed that the concentrations of several NEAAs including glutamine, serine, and arginine can be regionally depleted within the tumor microenvironment [16,17,18]. Therefore, the availability of an amino acid to be synthesized or consumed is the result of a complex interaction between tissue-specific gene expression programs, dietary consumption, and local consumption/secretion rates. This results in an inherent complexity in NEAA metabolism that introduces unique challenges when attempting to manipulate these pathways therapeutically, especially in cancer where the levels of nutrients are highly variable [18,19].

20개의 단백질 구성 아미노산은 두 개의 주요 하위 그룹으로 나눌 수 있습니다

—필수 아미노산(EAAs)과 비필수 아미노산(NEAAs) [12].

이 분류는 식이 필요성에 기반하며, 아미노산이 “…동물 유기체가 세포에 일반적으로 이용 가능한 재료로부터 정상적인 성장 요구에 맞는 속도로 합성할 수 없는 경우” 필수 아미노산으로 간주됩니다 [13].

인간에게는 9개의 필수 아미노산

(히스티딘, 이소류신, 류신, 라이신, 메티오닌, 페닐알라닌, 트레오닌, 트립토판, 발린)과

11개의 비필수 아미노산

(알라닌, 아스파르트산, 아스파라긴, 아르기닌, 시스테인, 글루타메이트, 글루타민, 글리신, 프로린, 세린, 티로신)이

있습니다.

In humans there are

9 essential amino acids

(histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine) and

11 non-essential amino acids

(alanine, aspartate, asparagine, arginine, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine).

hill mpttv

aaaa cggg pst

11개의 비필수 아미노산 중 최소 6개는

“조건부 필수 아미노산”으로 분류됩니다.

이는 특정 생리적 또는 병리적 조건에서

식이 섭취가 필요해지기 때문입니다.

예를 들어,

페닐케톤뇨증과 같은 선천성 대사 장애에서는

티로신이 더 이상 합성되지 않아 섭취가 필수적입니다 [14].

아미노산의 식이 필수성은

유기체 수준에서 고려됩니다.

이는 특정 세포 유형이나 조직이 일부 NEAA를 합성하거나 흡수할 수 없기 때문입니다.

또한 인간에서 11가지 NEAA의 혈중 농도는 매우 변동성이 크며,

아스파르테이트는 20 µM,

글루타민은 550 µM까지 다양합니다 [15].

또한 글루타민, 세린, 아르기닌을 포함한

여러 NEAA의 농도가 종양 미세환경 내에서

지역적으로 감소할 수 있다는 것이 관찰되었습니다 [16,17,18].

따라서

아미노산의 합성 또는 섭취 가능성은

조직 특이적 유전자 발현 프로그램,

식이 섭취,

현지 섭취/분비 속도 간의 복잡한 상호작용의 결과입니다.

이것은 NEAA 대사 과정에 내재된 복잡성을 초래하며,

특히 영양소 수준이 극도로 변동되는 암에서

이러한 경로를 치료적으로 조작할 때 독특한 도전 과제를 제시합니다 [18,19].

In this review, we will focus on the diversity of the metabolic roles that NEAAs play in cancer. In addition to being 11 of the 20 amino acids needed for protein synthesis, NEAAs are important for many other aspects of tumor metabolism, including nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis, maintenance of redox homeostasis, and numerous allosteric and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. The importance of these diverse roles has generated great interest in targeting NEAA metabolism for cancer therapy. Indeed, several NEAA-targeted therapies are already used for cancer treatment, and several others are being evaluated in clinical trials, while many more are being explored pre-clinically. The inherent complexity of NEAA metabolism has motivated the examination of numerous approaches for targeting these pathways for therapy, including inhibition of their biosynthetic pathways or key nodes of utilization, inhibition of cellular NEAA uptake, or depletion of plasma NEAA levels either through enzymatic degradation or restriction of NEAAs in the diet. In this review, we will briefly discuss each of the 11 NEAAs, how they function to support the pathology of cancer, and what strategies are currently used or are being developed for targeting NEAA metabolism for cancer therapy.

이 리뷰에서는

NEAA가 암에서 수행하는 대사 역할의 다양성에 초점을 맞출 것입니다.

단백질 합성에 필요한 20개 아미노산 중 11개를 차지하는 것 외에도,

NEAA는 핵산 및 지질 생합성,

환원-산화 균형 유지,

다양한 알로스테릭 및 에피게노믹 조절 메커니즘 등

종양 대사 과정의 여러 측면에 중요합니다.

이러한 다양한 역할의 중요성은

NEAA 대사 조절을 암 치료 표적으로 삼는 연구에 큰 관심을 불러일으켰습니다.

실제로 여러 NEAA 표적 치료법이 이미 암 치료에 사용되고 있으며,

다른 몇 가지 치료법은 임상 시험에서 평가 중이며,

많은 치료법이 전임상 단계에서 탐색 중입니다.

NEAA 대사 과정의 내재적 복잡성은

이러한 경로를 표적화하기 위한 다양한 접근 방식의 탐구를 촉진했습니다.

이는 생합성 경로의 억제,

이용의 핵심 단계 억제,

세포 내 NEAA 흡수 억제, 또는

효소적 분해나 식이 제한을 통해 혈장 내 NEAA 수준 감소 등이 포함됩니다.

이 리뷰에서는

11가지 NEAA 각각에 대해 간략히 논의하며,

이들이 암 병리학에 어떻게 기여하는지,

그리고 암 치료를 위해 NEAA 대사 경로를 표적화하기 위해

현재 사용 중이거나 개발 중인 전략들이 무엇인지 살펴보겠습니다.

2. Non-Essential Amino Acids

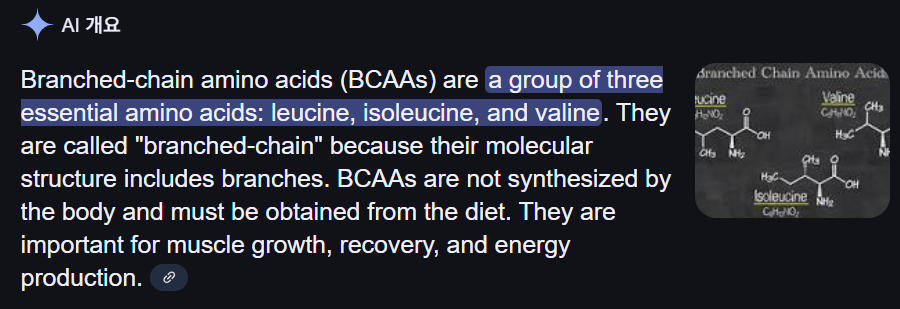

2.1. Glutamine

Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in human plasma [15] and is one of the most studied in the context of cancer metabolism [20,21,22]. Glutamine is also the amino acid that is consumed at the highest rate by cancer cells in culture and is well-established as being required for cancer cell proliferation [5,8]. This importance is likely due to glutamine’s ability to provide both carbon and nitrogen for many biosynthetic reactions. Carbon from glutamine, in the form of α-ketoglutarate (αKG), is an important anaplerotic substrate to support the biosynthetic functions of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [8,23], and glutamine-derived nitrogen is required for the biosynthesis of molecules such as hexosamines [9], nucleotides [10,11] and other NEAAs (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Glutamine can be taken up by cancer cells via a number of different amino acid transporters, among which ASCT2 (alanine/serine/cysteine transporter 2, coded for by the SLC1A5 gene) is the best described [24]. Glutamine uptake is significantly increased in tumors, and glutamine-based positron emission tomography (PET) assays—similar to those currently used in the clinic for glucose—are being developed as potential clinical imaging tools [6]. Accordingly, inhibition of glutamine transporters using either small molecules or monoclonal antibodies is being explored as a potential therapeutic option [25,26,27,28]. While there is an apparent net consumption of glutamine in most cancer types, glutamine can also be synthesized from glutamate and ammonia by glutamine synthetase (coded for by the GLUL gene) (Figure 1), a process that is also important in cancer under some circumstances [29,30]. In addition to traditional uptake via glutamine transporters or its biosynthetic pathway, macropinocytosis and proteolytic degradation of extracellular proteins can provide an additional source of glutamine and other amino acids [31].

2. 필수 아미노산이 아닌 아미노산

2.1. 글루타민

글루타민은

인간 혈장 내에서 가장 풍부한 아미노산입니다 [15]이며,

암 대사 연구에서 가장 많이 연구된 아미노산 중 하나입니다 [20,21,22].

글루타민은

배양된 암 세포에서 가장 높은 속도로 소비되는 아미노산이며,

암 세포 증식에 필수적이라는 것이 잘 알려져 있습니다 [5,8].

https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-023-00971-9

이 중요성은

글루타민이 많은 생합성 반응에

탄소와 질소를 모두 공급할 수 있는 능력에서 기인합니다.

글루타민에서 유래한 탄소는

α-케토글루타레이트(αKG) 형태로

트리카르복실산(TCA) 회로의 생합성 기능을 지원하는

그리고

글루타민에서 유래한 질소는

헥소사민[9], 뉴클레오티드[10,11] 및 기타 NEAAs(그림 1 및 그림 2)의 생합성에 필수적입니다.

글루타민은 다양한 아미노산 운반체를 통해 암 세포에 흡수될 수 있으며,

이 중 ASCT2(알라닌/세린/시스테인 운반체 2, SLC1A5 유전자에 의해 coded 됨)가

가장 잘 연구되었습니다[24].

글루타민 흡수량은 종양에서 현저히 증가하며,

글루타민 기반 양전자 방출 단층 촬영(PET) 검사—현재 임상에서 포도당에 사용되는 것과 유사한—는

잠재적 임상 영상 도구로 개발 중입니다[6].

이에 따라

글루타민 운반체를 소분자 또는 단일클론 항체로 억제하는 것이

잠재적 치료 옵션으로 탐구되고 있습니다[25,26,27,28].

대부분의 암 유형에서 글루타민의 순 소비가 관찰되지만,

글루타민은 글루타메이트와 암모니아로부터

글루타민 합성효소(GLUL 유전자에 의해编码됨)에 의해 합성될 수 있으며(그림 1),

이 과정은 특정 조건 하에서 암에서도 중요합니다[29,30].

전통적인 글루타민 운반체나 생합성 경로를 통한 흡수 외에도,

대식세포 내포작용(macropinocytosis)과

세포외 단백질의 단백질 분해는

글루타민 및 기타 아미노산의 추가 공급원이 될 수 있습니다 [31].

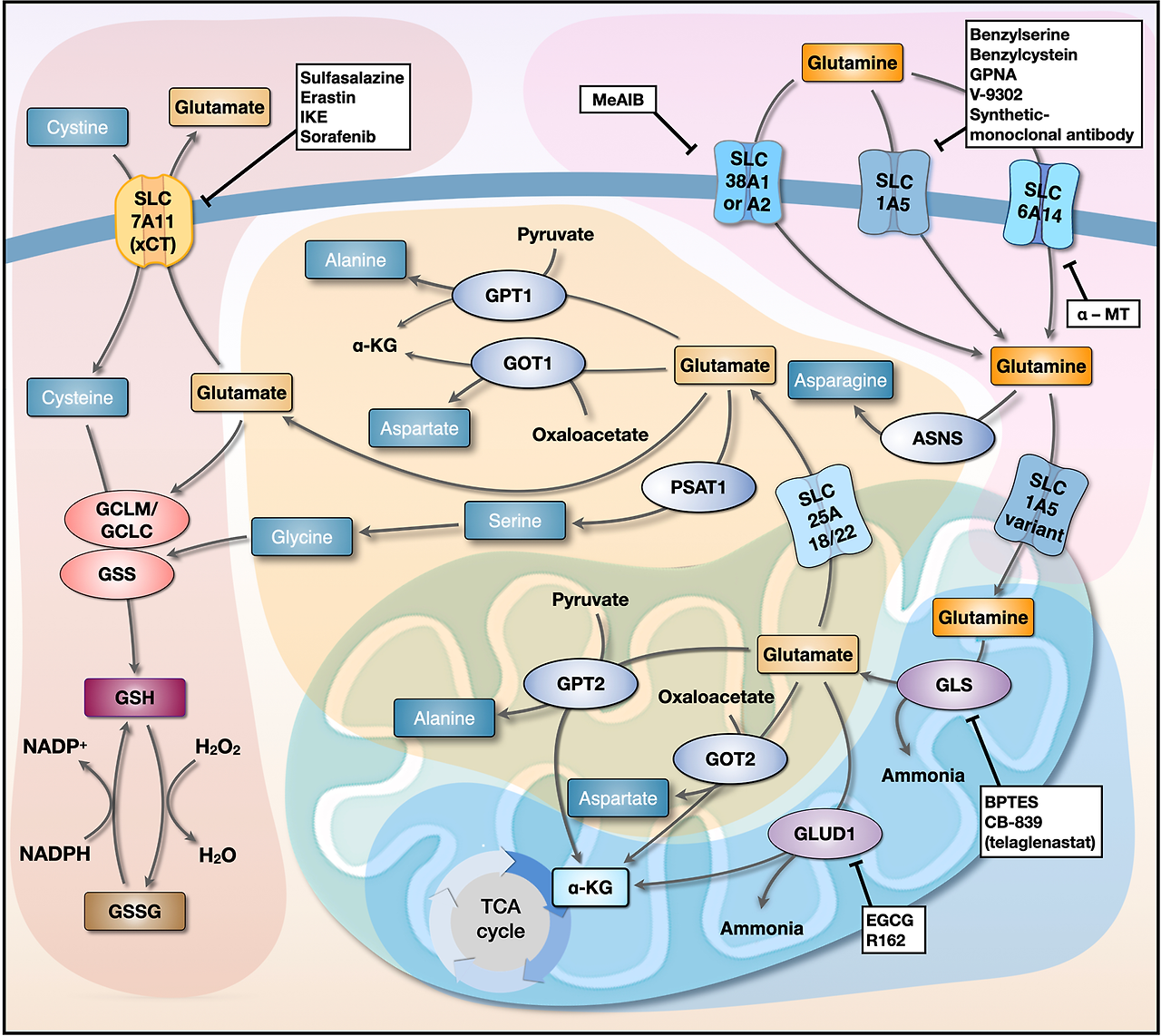

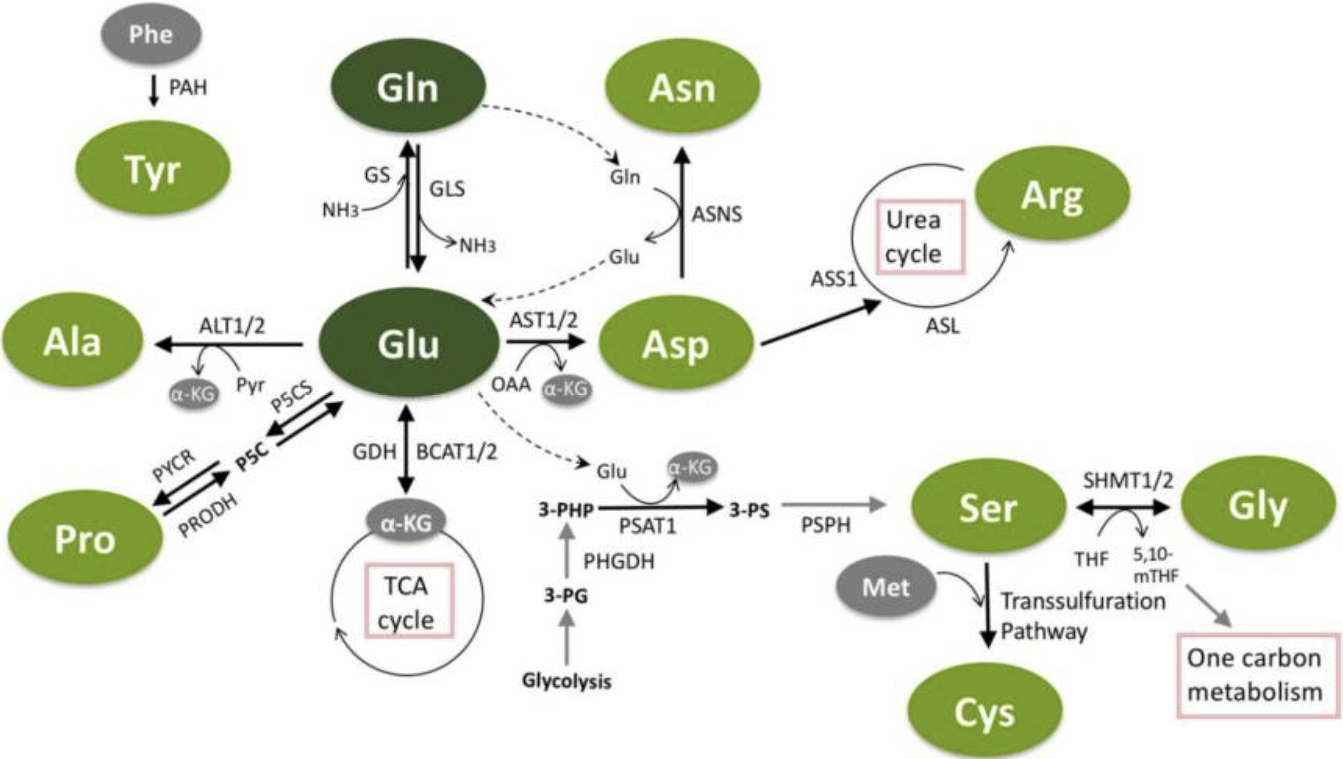

Figure 1.

The interconnected pathways of non-essential amino acids (NEAA) metabolism.

Glutamine and glutamate have a central role in non-essential amino acid metabolism, and can each be used for the synthesis of other NEAAs. Glutamate can be utilized to generate alanine, aspartate, serine and proline. Aspartate is further utilized to generate asparagine (with nitrogen from glutamine) and can be used in the urea cycle to make arginine. Serine donates methyl groups for one-carbon metabolism and makes glycine in the process. Serine can also be used in the transsulfuration pathway to generate cysteine. Tyrosine is the only NEAA not directly connected to the others, as it is separately synthesized from phenylalanine. Green circles indicate non-essential amino acids.

비필수 아미노산(NEAA) 대사 경로의 상호 연결성.

글루타민과 글루타메이트는

비필수 아미노산 대사에서 중심적인 역할을 하며,

각각 다른 NEAA의 합성에 사용될 수 있습니다.

글루타메이트는

알라닌, 아스파르트산, 세린, 프로린을 생성하는 데 활용될 수 있습니다.

아스파르트산은

글루타민으로부터 질소를 공급받아 아스파라긴을 생성하는 데 추가로 활용되며,

요산 순환에서 아르기닌을 합성하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

세린은 일탄소 대사에서 메틸 그룹을 공급하며,

이 과정에서 글리신을 생성합니다.

세린은

또한 트랜스설파화 경로를 통해 시스테인을 생성하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다.

티로신은

다른 아미노산과 직접 연결되지 않은 유일한 비필수 아미노산으로,

페닐알라닌으로부터 별도로 합성됩니다.

녹색 원은 비필수 아미노산을 표시합니다.

Abbreviations: Gln = glutamine; Glu = glutamate; Phe = phenylalanine; Tyr = tyrosine; Ala = alanine; Pro = proline; Asp = aspartate; Asn = asparagine; Arg = arginine; Ser = serine; Gly = glycine; Met = methionine; Cys = cysteine; α-KG = α-ketoglutarate; ALT1/2 = alanine aminotransferase 1/2; AST1/2 = aspartate aminotransferase 1/2; ASNS = asparagine synthetase; ASS1 = argininosuccinate synthetase 1; ASL = argininosuccinate lyase; BCAT1/2 = branched-chain aminotransferase 1/2; GDH = glutamate dehydrogenase; GLS = glutaminase; GS = glutamine synthetase; OAA = oxaloacetate; PAH = phenylalanine hydroxylase; PHGDH = phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; PSAT1 = phosphoserine aminotransferase 1; PSPH = phosphoserine phosphatase; P5CS = pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase; PRODH = proline dehydrogenase; PYCR = pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase; Pyr = pyruvate; 3-PG = 3-phosphoglycerate; 3-PHP = 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; 3-PS = 3-phosphoserine; SHMT1/2 = serine hydroxymethyltransferase-1/2; THF = tetrahydrofolate; 5,10-mTHF = 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; NH3 = ammonia.

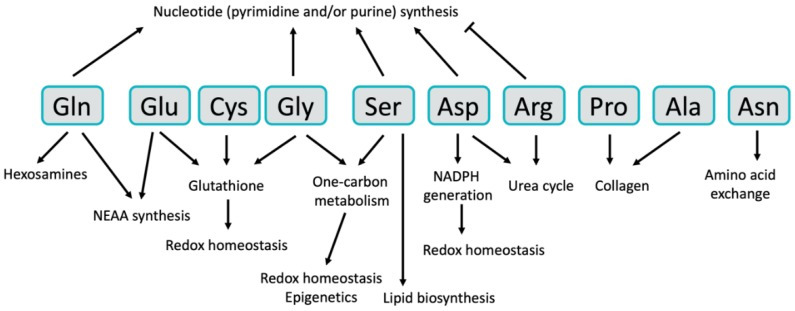

Figure 2.

The Diverse Functional Roles of NEAA in cancer. Non-essential amino acids have diverse functions in cancer cells.

NADPH = Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

While numerous approaches of targeting glutamine metabolism in cancer have been proposed and tested over the last several decades [32,33,34], inhibition of glutamine catabolism by glutaminase has emerged as a major focus of both academic and pharmaceutical cancer metabolism research. Glutaminase is an enzyme that mediates the conversion of glutamine to glutamate by removing the amide nitrogen from glutamine to generate glutamate and ammonia (Figure 1). Glutaminase activity has been demonstrated to be critical for the growth of most cancer cells in culture, and several inhibitors of glutaminase have been developed [35,36,37]. The most clinically relevant glutaminase inhibitor, CB-839, has shown pre-clinical activity in a variety of mouse models and is currently in clinical trials for several tumor types [36]. While these glutaminase inhibitors are effective against most cancer cells grown in culture, often times they are less effective in mouse models of cancer [38,39]. One explanation for this in vitro versus in vivo discrepancy is the relatively high concentration of cystine in tissue culture media relative to human plasma [40]. Cystine, which is the oxidized dimer form of the NEAA cysteine (discussed in more detail below), is transported into cells in exchange for glutamate by the transporter xCT (coded for by the SLC7A11 gene). High extracellular cystine can drive glutaminase activity by depleting the intracellular glutamate pool, thus making cancer cells more dependent on glutaminase to replenish intracellular glutamate [40]. This phenomenon also occurs in tumors with mutations in the Keap1/Nrf2 axis, as Nrf2 is the primary transcriptional driver of xCT expression [41]. These studies suggest that tumors with elevated xCT expression will be good candidates for treatment with glutaminase inhibitors. Importantly, there are additional mechanisms of resistance to glutaminase inhibition, including the ability to synthesize glutamine via glutamine synthetase [29,38,42]. Inhibition of glutaminase has also shown pre-clinical activity as part of combination therapy in several tumor types [39,43,44], further expanding the potential impact that targeting glutaminase could have on cancer treatment.

최근 수십 년간 암 치료를 위해

글루타민 대사 경로를 표적으로 삼는 다양한 접근법이 제안되고 테스트되어 왔습니다[32,33,34].

그 중 글루타민 분해 효소인

글루타민아제(glutaminase)를 통해

글루타민 대사 과정을 억제하는 방법이

학계와 제약업계의 암 대사 연구에서 주요 초점으로 부상했습니다.

글루타민아제는

글루타민에서 아미드 질소를 제거하여

글루타메이트와 암모니아를 생성하는 과정에서

글루타민을 글루타메이트로 전환시키는 효소입니다(그림 1).

글루타민아제 활성은

대부분의 암 세포의 배양 성장에 필수적임이 입증되었으며,

여러 글루타민아제 억제제가 개발되었습니다 [35,36,37].

임상적으로 가장 관련성이 높은

글루타민아제 억제제인 CB-839는 다양한 마우스 모델에서 전임상 활성을 보여주었으며,

현재 여러 종양 유형에 대한 임상 시험 중입니다 [36].

그러나 이러한 글루타미나제 억제제는 배양된 대부분의 암 세포에 효과적이지만, 종종 마우스 암 모델에서는 덜 효과적입니다[38,39]. 이 체외(in vitro)와 체내(in vivo) 간의 차이의 한 가지 설명은 조직 배양 매체에서 시스테인의 농도가 인간 혈장보다 상대적으로 높기 때문입니다[40].

시스테인은

NEAA 시스테인의 산화 이량체 형태로,

글루타메이트와 교환되어 세포 내로 운반되는 운반체 xCT(SLC7A11 유전자에 의해编码됨)에 의해

세포 내로 운반됩니다.

세포 외 시스테인 농도가 높으면

세포 내 글루타메이트 풀을 고갈시켜 글루타미나제 활성을 촉진하며,

이는 암 세포가 세포 내 글루타메이트를 보충하기 위해

글루타미나제에 더 의존하게 만듭니다 [40].

이 현상은 Keap1/Nrf2 축에 돌연변이가 있는 종양에서도 발생합니다. Nrf2는 xCT 발현의 주요 전사 조절자이기 때문입니다 [41]. 이러한 연구 결과는 xCT 발현이 증가한 종양이 글루타미나제 억제제 치료의 좋은 후보가 될 수 있음을 시사합니다.

중요하게도,

글루타미나제 억제에 대한 추가적인 저항 메커니즘이 존재하며,

이는 글루타미나 합성효소(glutamine synthetase)를 통해

글루타미나제 억제는

여러 종양 유형에서 조합 요법의 일부로 전임상 활성을 보여주었으며 [39,43,44],

이는 글루타미나제를 표적으로 하는 치료법이 암 치료에 미칠 수 있는 잠재적 영향을 더욱 확장합니다.

2.2. Glutamate

In contrast to glutamine, glutamate is not found in high concentrations in human plasma and is not typically taken up in large quantities by cancer cells. Rather, most intracellular glutamate is derived from glutamine via glutaminase (Figure 1). Glutamate can also be synthesized from branched-chain amino acids and αKG via the activity of branched-chain amino transferases (BCAT1/2), representing an important link between EAA and NEAA metabolism that is utilized in some tumors [43,45]. Glutamate occupies a central hub in NEAA metabolism, as it is important for the biosynthesis of proline, aspartate, alanine and serine, which are in turn used for the synthesis of cysteine, glycine, asparagine and arginine (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Glutamate is converted to αKG either through the action of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), which removes the glutamate-derived nitrogen as ammonia, or via transaminases, which transfer the nitrogen from glutamate to an α-keto acid to generate other NEAAs (Figure 1). While either route results in the generation of αKG for TCA cycle anaplerosis, the utilization of glutamate-derived nitrogen for NEAA biosynthesis may be favored in rapidly proliferating cancer cells as a mechanism of preserving nitrogen for anabolic reactions [46]. Nevertheless, inhibition of GDH, either alone or with other treatments, has been shown to inhibit tumor growth in some cancers [47,48,49,50,51], suggesting that GDH activity is important in tumors under certain circumstances. Interestingly, GDH has also been shown to operate in reverse in some breast cancer cells where it can fix nitrogen from ammonia to provide an additional source of glutamate [52]. Glutamate utilization by transaminases to generate NEAAs has also been shown to be required for tumor growth in a variety of cancer types [49,53,54,55]. Glutamate is also used for the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione (Figure 2) [56], which is discussed in more detail in the section on cysteine. The numerous sources of glutamate available to cancer cells and the variety of pathways by which glutamate can be utilized make targeting glutamate metabolism for therapy challenging, and are an excellent example of the redundancy found in many NEAA metabolic pathways.

2.2. 글루타메이트

글루타민과 달리,

글루타메이트는 인간 혈장에서는 높은 농도로 존재하지 않으며

암 세포에 의해 대량으로 흡수되지 않습니다.

대신,

세포 내 글루타메이트의 대부분은

글루타미나아제(그림 1)를 통해 글루타민에서 유래됩니다.

글루타메이트는 분지쇄 아미노산과 αKG를 통해

분지쇄 아미노산 전이효소(BCAT1/2)의 활성을 통해 합성될 수 있으며,

이는 일부 종양에서 활용되는 필수 아미노산(EAA)과 비필수 아미노산(NEAA) 대사 사이의

글루타메이트는

NEAA 대사에서 중심 허브 역할을 하며,

프로린, 아스파르트산, 알라닌, 세린의 생합성에 중요하며,

이는 다시 시스테인, 글리신, 아스파라긴, 아르기닌의 합성에 사용됩니다(그림 1 및 그림 2).

글루타메이트는

글루타메이트 탈수소효소(GDH)의 작용을 통해 글

루타메이트에서 유래한 질소를 암모니아로 제거하거나,

트랜스아미나아제(transaminases)를 통해 글루타메이트의 질소를 α-케토산으로 전달하여

다른 NEAA를 생성하는 두 가지 경로를 통해

α-케토글루타메이트(αKG)로 전환됩니다(그림 1).

두 경로 모두

TCA 사이클의 아나플로레시스(anaplerosis)를 위해

αKG를 생성하지만,

빠르게 증식하는 암 세포에서는 아미노산 합성에 필요한 질소를 보존하기 위한 메커니즘으로

글루타메이트 유래 질소의 NEAA 생합성에 활용될 수 있습니다 [46].

그러나

GDH를 단독으로 또는 다른 치료법과 함께 억제하는 것이

일부 암에서 종양 성장 억제를 유발한다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다[47,48,49,50,51],

이는 특정 조건 하에서 GDH 활성이 종양에서 중요함을 시사합니다.

흥미롭게도

일부 유방암 세포에서는 GDH가 역방향으로 작동하여

암모니아로부터 질소를 고정해 글루타메이트의 추가 공급원을 제공한다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다[52].

글루타메이트를 트랜스아미나아제(transaminases)를 통해 NEAA로 전환하는 과정은

다양한 암 유형에서 종양 성장에 필수적이라는 것이 밝혀졌습니다 [49,53,54,55].

글루타메이트는

항산화제 글루타티온(그림 2)의 합성에도 사용되며,

이는 시스테인 섹션에서 자세히 논의됩니다.

암 세포에 이용 가능한 글루타메이트의 다양한 공급원과 글루타메이트가 활용되는 다양한 경로는

글루타메이트 대사 경로를 표적으로 하는 치료법을 개발하는 데 도전 과제를 제시하며,

이는 많은 NEAA 대사 경로에서 발견되는 중복성의 우수한 예시입니다.

2.3. Serine

Serine is another NEAA that has garnered a great deal of attention from the cancer metabolism community. Like glutamine, serine can be taken up by numerous transporters including ASCT2 [57]. Serine is synthesized de novo by the serine synthesis pathway, which diverts 3-phosphoglycerate from glycolysis and utilizes nitrogen from glutamate in a three-step pathway (Figure 1). The gene for the first enzyme of the pathway, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), has been shown to be focally amplified in some triple-negative breast cancers and melanomas [58,59]. PHGDH and the other enzymes in the serine synthesis pathway—phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) and phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH)—can also be activated in cancer cells by epigenetic mechanisms [60] and by the transcription factor ATF4 downstream of both mTOR and Nrf2 signaling [61,62]. Serine is an important NEAA in cancer cells for several reasons, including its participation in purine biosynthesis [61,62], mitochondrial protein translation [63], lipid biosynthesis [64], and as an allosteric regulator of glycolysis [65] (Figure 2). Serine is also a critical donor of methyl groups for one-carbon metabolism, which will be discussed in the next section on glycine.

Because of its clear importance in proliferative metabolism, numerous approaches of targeting serine metabolism in tumors have been explored. Several academic laboratories and pharmaceutical companies have developed PHGDH inhibitors that have shown efficacy in some tumor models [66,67,68,69]. However, inhibition of PHGDH is not always sufficient to inhibit tumor growth [70,71], in part because serine is readily available in human plasma and can be taken up to compensate for a loss of serine biosynthesis. Interestingly, PHGDH and the serine synthesis pathway seem to be of greater importance for tumors growing in tissues that have low availability of serine in the extracellular environment [19]. In addition to inhibition of serine biosynthesis, the manipulation of serine availability by removing serine and glycine from the diet has been explored in mice as a potential therapeutic option [72,73,74]. Dietary restriction has been shown to reduce plasma serine levels by up to 75% and is effective at limiting tumor growth in a p53- and antioxidant-dependent fashion [72,73]. However, the effectiveness of dietary serine deprivation is also dependent on the ability of the tumors to synthesize serine de novo [19,73]. These results demonstrate a complex but important interplay between serine biosynthesis and extracellular serine availability in tumors and their environment, making it likely that identifying the appropriate approach for specific tumor types will be important if we wish to successfully target serine metabolism for cancer therapy.

2.3. 세린

세린은

암 대사 연구 커뮤니티에서 많은 관심을 받은

또 다른 NEAA입니다.

글루타민과 마찬가지로

세린은 ASCT2를 포함한 다양한 운반체를 통해 흡수됩니다 [57].

세린은

세린 합성 경로를 통해 글리코lysis에서 분기된

3-포스포글리세레이트를 활용하고

글루타메이트로부터 질소를 공급받아 3단계 경로로 합성됩니다 (그림 1).

이 경로의 첫 번째 효소인 포스포글리세레이트 데히드로게나제 (PHGDH) 유전자는 일부 삼중 음성 유방암과 흑색종에서 국소적으로 증폭된 것으로 보고되었습니다 [58,59]. PHGDH와 세린 합성 경로의 다른 효소인 포스포세린 아미노트랜스퍼라제 1(PSAT1) 및 포스포세린 인산화효소(PSPH)는 에피제네틱 메커니즘[60] 및 mTOR와 Nrf2 신호전달 경로 하류의 전사 인자 ATF4에 의해 암 세포에서 활성화될 수 있습니다[61,62]. 세린은 암 세포에서 여러 이유로 중요한 필수 아미노산(NEAA)입니다. 이는 푸린 생합성[61,62], 미토콘드리아 단백질 번역[63], 지질 생합성[64], 그리고 글리코lysis의 알로스테릭 조절자로서의 역할[65] (그림 2)에 참여하기 때문입니다. 세린은 또한 다음 섹션에서 논의될 글리신과 관련된 일탄소 대사에서 메틸 그룹의 중요한 공급원입니다.

증식 대사에서의 명확한 중요성 때문에, 종양에서 세린 대사 표적화 접근법이 다수 탐구되었습니다. 여러 학술 연구실과 제약 회사는 일부 종양 모델에서 효능을 보인 PHGDH 억제제를 개발했습니다 [66,67,68,69]. 그러나 PHGDH 억제는 종양 성장 억제에 항상 충분하지 않습니다 [70,71], 이는 부분적으로 세린이 인간 혈장에서 쉽게 이용 가능하며 세린 생합성 손실을 보상하기 위해 흡수될 수 있기 때문입니다. 흥미롭게도 PHGDH와 세린 합성 경로는 세린이 세포 외 환경에서 낮은 농도로 존재하는 조직에서 성장하는 종양에서 더 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 보입니다 [19]. 세린 생합성 억제 외에도, 식이에서 세린과 글리신을 제거하여 세린 가용성을 조작하는 방법이 마우스에서 잠재적 치료 옵션으로 탐구되었습니다 [72,73,74]. 식이 제한은 혈장 세린 수치를 최대 75%까지 감소시키며, p53 및 항산화제 의존적 방식으로 종양 성장을 제한하는 데 효과적입니다 [72,73]. 그러나 식이 세린 결핍의 효과는 종양이 세린을 신합성하는 능력에 따라 달라집니다 [19,73]. 이러한 결과는 종양과 그 환경에서 세린 생합성과 세린 가용성 사이의 복잡하지만 중요한 상호작용을 보여주며, 특정 종양 유형에 맞는 적절한 접근법을 식별하는 것이 세린 대사 표적 치료를 성공적으로 수행하기 위해 중요할 것임을 시사합니다.

2.4. Glycine

Serine and glycine metabolism are closely linked, as glycine is directly generated from serine via the serine hydroxymethyltransferase enzymes SHMT1 and SHMT2 (Figure 1). Importantly, the conversion of serine to glycine provides one-carbon units that are utilized by the folate and methionine cycles in the metabolic pathways collectively referred to as one-carbon metabolism. Serine, glycine, and their relation to one-carbon metabolism are highly relevant aspects of tumor metabolism that have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [75,76,77]. One-carbon metabolism is essential for the pathological functions of cancer cells for a variety of reasons, including nucleotide biosynthesis [78], nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) regeneration and redox homeostasis [79], protein translation [80], and epigenetic modifications [81] (Figure 2). The importance of one-carbon metabolism in cancer has been appreciated for decades. In fact, inhibition of the folate cycle was among the first effective chemotherapeutic treatments for cancer [82]. Despite these initial clinical discoveries over 70 years ago, inhibitors of folate metabolism like methotrexate are still utilized for cancer treatment today and remain an active area of research in the cancer metabolism field [75,76,77]. For example, histidine catabolism was recently shown to impact the efficacy of methotrexate treatment by reducing the cellular pool of tetrahydrofolate, suggesting that dietary histidine supplementation may improve patient response to methotrexate [83]. Not surprisingly, targeting glycine metabolism using inhibitors of the SHMT enzymes is also being explored as a potential therapeutic option [80,84,85]. Uptake of glycine from the extracellular environment [7] and the downstream utilization of glycine via the glycine cleavage system [86,87] also play important roles in cancer cells and are being investigated as potential therapeutic targets.

2.4. 글리신

세린과 글리신 대사는 밀접하게 연결되어 있습니다.

글리신은

세린 하이드록시메틸트랜스퍼레이즈 효소 SHMT1과 SHMT2를 통해

세린에서 직접 생성됩니다(그림 1).

중요하게도,

세린에서 글리신으로의 전환은

엽산과 메티오닌 순환에 의해 활용되는 1탄소 단위를 제공합니다.

이 대사 경로는 1탄소 대사라고 총칭됩니다.

세린, 글리신 및 일탄소 대사와의 관계는

종양 대사에서 매우 중요한 측면으로,

다른 문헌에서 광범위하게 검토되었습니다 [75,76,77].

1탄소 대사는 다양한 이유로 암 세포의 병리적 기능에 필수적입니다.

이는 핵산 생합성 [78],

니코틴아미드 아데닌 디뉴클레오티드 인산(NADPH) 재생 및 산화환원 균형 [79],

단백질 번역 [80],

에피제네틱 변형 [81] (그림 2) 등을 포함합니다.

암에서 일탄소 대사 과정의 중요성은 수십 년 동안 인식되어 왔습니다.

실제로 엽산 순환의 억제는

암에 대한 첫 번째 효과적인 화학요법 치료법 중 하나였습니다 [82]. 7

0년 전의 초기 임상 발견에도 불구하고,

엽산 대사 억제제인 메토트렉세이트는

오늘날까지 암 치료에 사용되고 있으며,

암 대사 분야에서의 활발한 연구 분야로 남아 있습니다 [75,76,77].

예를 들어,

히스티딘 대사 과정이 테트라히드로엽산의 세포 내 풀을 감소시켜

메토트렉세이트 치료의 효과를 저해한다는 것이 최근 밝혀졌으며,

이는 식이 히스티딘 보충이 메토트렉세이트에 대한 환자 반응을 개선할 수 있음을 시사합니다 [83].

예상대로,

SHMT 효소 억제제를 활용한 글리신 대사 표적화도

잠재적 치료 옵션으로 탐구되고 있습니다 [80,84,85].

세포 외 환경으로부터의 글리신 흡수 [7] 및 글리신 분해 시스템을 통한 글리신의 하류 이용 [86,87]도

암 세포에서 중요한 역할을 하며 잠재적 치료 표적으로 연구되고 있습니다.

2.5. Aspartate

Numerous recent studies have demonstrated a particularly important role for aspartate metabolism in cellular proliferation and cancer. Aspartate is generated from oxaloacetate and glutamate-derived nitrogen by aspartate aminotransferase enzymes (Figure 1), of which there are cytosolic and mitochondrial isoforms (coded for by the GOT1 and GOT2 genes, respectively). The role of aspartate in transferring electrons between the cytosol and mitochondria via the malate–aspartate shuttle is well understood and as such it is believed that the majority of aspartate synthesis in rapidly proliferating cells occurs in the mitochondria [88]. Indeed, transport of aspartate from the mitochondria to the cytosol via the aspartate–glutamate carrier is important for cell survival under certain conditions [89]. As mentioned, the concentration of aspartate in plasma is the lowest among the proteinogenic amino acids [15] and aspartate is not efficiently transported into most cancer cells [88], suggesting that biosynthesis via aspartate aminotransferase is the most relevant source of aspartate in most cancer cells. Aspartate is essential for the synthesis of both purine and pyrimidine nucleotides (Figure 2), and as such aspartate synthesis is very closely linked to cellular proliferation [46]. Aspartate metabolism can also be an important source of NADPH utilized for the neutralization of reactive oxygen species in certain cell types, thereby promoting biosynthesis and cellular survival [49].

Several recent reports have uncovered an interesting connection between the mitochondrial electron transport chain and aspartate biosynthesis. These studies have suggested that the essential function of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in proliferating cells is to facilitate aspartate biosynthesis [88,90]. In this model, the electron transport chain serves as an electron acceptor, consuming nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to regenerate NAD+, which can then be utilized for oxaloacetate generation and aspartate biosynthesis. Indeed, provision of exogenous aspartate is sufficient to rescue electron transport chain deficiency in cancer cells [88,90]. This result is remarkable given the numerous other functions of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation but, nevertheless, stresses the importance of aspartate biosynthesis in proliferative cells. Importantly, aspartate availability has recently been shown to be limiting for tumor growth in vivo [91], and inhibition of aspartate biosynthesis can inhibit tumor growth [49,53]. These studies demonstrate the utmost importance of aspartate in cancer and have motivated the development of inhibitors of aspartate aminotransferases as potential cancer therapeutics [92,93].

2.5. 아스파르트산

최근 수많은 연구에서

아스파르테이트 대사 과정이

세포 증식과 암에서 특히 중요한 역할을 한다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다.

아스파르테이트는

옥살아세테이트와 글루타메이트에서 유래한 질소를

아스파르테이트 아미노전달효소(그림 1)에 의해 생성되며,

이 효소는 세포질과 미토콘드리아에 존재하는 이소형(각각 GOT1 및 GOT2 유전자에 의해编码됨)으로 구분됩니다.

아스파르테이트가

말레이트-아스파르테이트 셔틀을 통해 세포질과 미토콘드리아 사이에서

전자 전달에 관여하는 역할은 잘 알려져 있으며,

따라서 빠르게 증식하는 세포에서 아스파르테이트 합성의 대부분이 미토콘드리아에서 발생한다고 믿어집니다 [88].

실제로, 특정 조건 하에서 아스파르테이트-글루타메이트 운반체를 통해 미토콘드리아에서 세포질로 아스파르테이트가 운반되는 것은 세포 생존에 중요합니다 [89]. 앞서 언급된 바와 같이, 혈장 내 아스파르트산 농도는 단백질 생성 아미노산 중 가장 낮으며 [15], 아스파르트산은 대부분의 암 세포로 효율적으로 운반되지 않습니다 [88]. 이는 대부분의 암 세포에서 아스파르트산 아미노전달효소를 통한 생합성이 아스파르트산의 주요 공급원임을 시사합니다. 아스파르테이트는 푸린과 피리미딘 핵산(그림 2)의 합성에 필수적이며, 따라서 아스파르테이트 합성은 세포 증식과 매우 밀접하게 연관되어 있습니다[46]. 아스파르테이트 대사도 특정 세포 유형에서 활성 산소 종의 중화 위해 NADPH의 중요한 공급원이 될 수 있으며, 이는 생합성과 세포 생존을 촉진합니다[49].

최근 몇 가지 보고서는 미토콘드리아 전자 전달 사슬과 아스파르테이트 생합성 사이의 흥미로운 연관성을 밝혀냈습니다. 이 연구들은 증식 중인 세포에서 미토콘드리아 전자 전달 사슬의 필수적 기능이 아스파르트산 생합성을 촉진하는 것임을 제안했습니다 [88,90]. 이 모델에서 전자 전달 사슬은 전자 수락체로 작용하여 니코틴아미드 아데닌 디뉴클레오티드(NADH)를 소비해 NAD+를 재생성하며, 이는 옥살아세트산 생성 및 아스파르트산 생합성에 활용됩니다.

실제로,

암 세포에서 전자 전달 사슬 결핍을 회복하기 위해

외부 아스파르트산을 공급하는 것만으로도 충분합니다 [88,90].

이 결과는

미토콘드리아 산화 인산화 반응의 수많은 다른 기능에도 불구하고,

증식 세포에서 아스파르트산 생합성의 중요성을 강조합니다.

특히,

아스파르트산 가용성이 최근 생체 내 종양 성장의 제한 요인으로 밝혀졌으며 [91],

아스파르트산 생합성을 억제하면 종양 성장이 억제됩니다 [49,53].

이러한 연구들은

아스파르테이트가 암에서 갖는 극히 중요한 역할을 입증했으며,

아스파르테이트 아미노트랜스퍼레이즈 억제제를 잠재적 암 치료제로 개발하는 동기를 제공했습니다 [92,93].

2.6. Asparagine

Asparaginase, an injectable enzymatic drug that degrades asparagine in the plasma, is a “cornerstone” of treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [94]. Thus, asparaginase is likely the most prominent example of a current cancer therapy that directly targets NEAA metabolism. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells are sensitive to the depletion of asparagine in the plasma in part because they lack significant expression of asparagine synthetase (coded for by the ASNS gene) [94,95], the enzyme that synthesizes asparagine using aspartate and nitrogen from glutamine (Figure 1). This results in a severe lack of asparagine for protein synthesis in ALL cells and subsequent induction of apoptosis. Resistance to asparaginase treatment can occur in ALL and is commonly caused by induction of asparagine synthetase expression and a renewed ability to synthesize asparagine [95]. Accordingly, asparagine synthetase inhibitors have been developed and can overcome resistance to asparaginase treatment [96,97]. While the clinical utility of asparaginase makes it clear that asparagine is essential for tumor growth, the importance of asparagine beyond protein synthesis is less understood. However, asparagine has been shown to function as an important exchange factor needed for the uptake of other amino acids that are required for the activation of mTOR signaling (Figure 2) [98]. This suggests a potential feedback mechanism where low asparagine levels can be sensed by mTOR signaling to reduce the rates of protein synthesis. Interestingly, intracellular asparagine levels have recently been shown to be required for breast cancer metastasis [99], suggesting that asparaginase treatment, dietary asparagine limitation, or inhibition of asparagine synthetase may be effective treatment options for metastatic breast cancer.

2.6. 아스파라긴

아스파라긴은 혈장 내 아스파라긴을 분해하는 주사제 형태의 효소 약물로, 급성 림프구성 백혈병(ALL) 치료의 '기초'로 알려져 있습니다 [94]. 따라서 아스파라긴아제는 현재 암 치료제 중 NEAA 대사 과정을 직접 표적하는 가장 대표적인 예시입니다. 급성 림프구성 백혈병 세포는 혈장 내 아스파라긴 부족에 민감한데, 이는 아스파라긴 합성효소(ASNS 유전자에 의해编码됨)의 발현이 부족하기 때문입니다[94,95]. 이 효소는 아스파르트산과 글루타민에서 유래한 질소를 사용하여 아스파라긴을 합성합니다(그림 1). 이로 인해 ALL 세포에서 단백질 합성에 필요한 아스파라긴이 심각하게 부족해지며, 이는 세포 사멸을 유발합니다. 아스파라긴아제 치료에 대한 저항성은 ALL에서 발생할 수 있으며, 이는 주로 아스파라긴 합성효소 발현 유도 및 아스파라긴 합성 능력의 회복에 의해 유발됩니다 [95]. 이에 따라 아스파라긴 합성효소 억제제가 개발되었으며, 이는 아스파라긴아제 치료에 대한 저항성을 극복할 수 있습니다 [96,97]. 아스파라긴아제의 임상적 유용성은 아스파라긴이 종양 성장에 필수적임을 명확히 하지만, 단백질 합성 beyond 아스파라긴의 중요성은 덜 이해되고 있습니다. 그러나 아스파라긴은 mTOR 신호전달 활성화에 필요한 다른 아미노산의 흡수 위해 필요한 중요한 교환 인자로 기능함이 밝혀졌습니다 (그림 2) [98]. 이는 아스파라긴 수준이 낮을 때 mTOR 신호전달이 이를 감지하여 단백질 합성 속도를 감소시키는 잠재적 피드백 메커니즘을 시사합니다. 흥미롭게도 최근 연구에서 세포 내 아스파라긴 수준이 유방암 전이에 필수적이라는 것이 밝혀졌습니다[99], 이는 아스파라긴아제 치료, 식이 아스파라긴 제한, 또는 아스파라긴 합성효소 억제가 전이성 유방암의 효과적인 치료 옵션이 될 수 있음을 시사합니다.

2.7. Alanine

Alanine lies at a central hub of carbon metabolism, being synthesized by alanine aminotransferases (coded for by the GPT and GPT2 genes) using carbon from pyruvate and nitrogen from glutamate (Figure 1). Despite these connections to highly cancer-relevant metabolic pathways, the role of alanine in cancer is less understood relative to some other NEAAs. It is interesting to speculate that this may be in part because of a discrepancy between the concentration of alanine in human plasma, where it is the second most abundant amino acid, and in most tissue culture medias, which have little to no alanine [15]. This forces cancer cells in culture to synthesize nearly all of their alanine regardless of whether this would normally occur in a tumor, and has the potential to lead to tissue culture-generated artifacts. This stresses the potential importance of using tissue culture media that more accurately represent the nutrient levels found in vivo [15,29,40,100]. Despite these inconsistencies, there is some emerging evidence of the importance of alanine metabolism in cancer. For example, biosynthesis of alanine has been shown to be correlated with proliferation, suggesting that it may play a role in proliferative cell metabolism [46]. Alanine is also an important survival signal in pancreatic cancer, where stromal cells promote the proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells by secreting alanine that can be utilized in the TCA cycle of the cancer cells [101]. In addition, a recent report has demonstrated that alanine aminotransferase is an important source of αKG for the hydroxylation of collagen and the preparation of the metastatic niche in breast cancer (Figure 2) [102]. These studies suggest that alanine indeed plays an important role in cancer biology, but additional work will likely be needed to motivate the development of alanine-targeted therapies.

2.7. 알라닌

알라닌은 탄소 대사 중심에 위치하며, 피루vate에서 탄소와 글루타메이트에서 질소를 사용하여 알라닌 아미노전달효소(GPT 및 GPT2 유전자에 의해编码됨)에 의해 합성됩니다(그림 1). 이러한 암과 관련된 대사 경로와의 연결에도 불구하고, 알라닌의 암에서의 역할은 다른 일부 NEAAs에 비해 덜 이해되고 있습니다. 인간 혈장에서는 두 번째로 풍부한 아미노산인 알라닌의 농도와 대부분의 조직 배양 매체에서 알라닌이 거의 또는 전혀 존재하지 않는다는 점 사이의 불일치가 일부 원인일 수 있다는 추측이 흥미롭습니다[15]. 이는 배양된 암 세포가 종양에서 일반적으로 발생하지 않더라도 거의 모든 알라닌을 합성하도록 강요하며, 조직 배양에 의한 인공적 현상을 유발할 수 있습니다. 이는 체내에서 발견되는 영양소 수준을 더 정확히 반영하는 조직 배양 매체를 사용하는 것이 중요할 수 있음을 강조합니다 [15,29,40,100]. 이러한 불일치에도 불구하고 알라닌 대사 과정의 중요성을 시사하는 일부 새로운 증거가 등장하고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 알라닌 생합성이 증식과 관련이 있다는 것이 밝혀졌으며, 이는 증식성 세포 대사에서 역할을 할 수 있음을 시사합니다 [46]. 알라닌은 췌장암에서 중요한 생존 신호로 작용하며, Stromal 세포가 암 세포의 TCA 회로에서 활용될 수 있는 알라닌을 분비하여 췌장암 세포의 증식과 생존을 촉진합니다 [101]. 또한 최근 보고서는 알라닌 아미노전달효소가 유방암에서 콜라겐의 수산화 및 전이 미세환경 형성에 중요한 αKG의 주요 공급원임을 보여주었습니다 (그림 2) [102]. 이 연구들은 알라닌이 암 생물학에서 중요한 역할을 한다는 것을 시사하지만, 알라닌을 표적으로 한 치료법 개발을 촉진하기 위해서는 추가 연구가 필요할 것입니다

2.8. Cysteine

One of two sulfur-containing proteinogenic amino acids, cysteine is unique in that it contains a reactive thiol side chain that endows several functions not possible with other amino acids. For example, reactive cysteine residues are often found in the catalytic site of enzymes where they function as a nucleophile in enzyme-catalyzed reactions [103]. Cysteine also forms disulfide bonds with other cysteines, a function that is critical in promoting protein folding and stability [104]. Reactive cysteine residues are also the driving force behind the ability of antioxidants to quench reactive oxygen species [104,105]. These diverse functional roles have made cysteine one of the more heavily studied NEAAs in cancer. Cysteine can be synthesized de novo from serine and methionine in a pathway known as the transsulfuration pathway (Figure 1). While this pathway has been shown to contribute to cysteine production in cancer cells under certain circumstances [106,107,108], the majority of intracellular cysteine is taken up from the extracellular environment either as cysteine [109] or in its oxidized dimer form, cystine. Cystine is transported into cells via the transporter xCT and then reduced to cysteine by thioredoxin reductase 1 and glutathione reductase [110]. Cystine uptake plays an important role in cancer, as evidenced by numerous attempts at inhibiting xCT as a potential therapeutic target in cancer [111,112,113,114]. Interestingly, inhibition of cystine uptake induces a unique form of cell death known as ferroptosis [115], the molecular components of which are also being tested as potential cancer therapeutics [116,117,118]. Enzymatic depletion of plasma cystine and cysteine—similar to the approach used for asparagine with asparaginase—can also suppress tumor growth [119]. Importantly, the predominant transcriptional regulator of cysteine metabolism—the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway—is mutated in numerous tumor types [120,121,122] and can be activated by oncogenic signaling pathways such as KRas and PI3K [123,124], suggesting that downstream control of cysteine metabolism is an important oncogenic function.

As mentioned, one of the key functions of cysteine in cancer is its role in reactive oxygen defense as part of several antioxidant systems (Figure 2) [105]. Of particular relevance for this review is the metabolite antioxidant glutathione, which is a tripeptide synthesized from three NEAAs—cysteine, glutamate and glycine [56]. The potential importance of glutathione metabolism in cancer is evidenced by the observation that glutathione is one of the most significantly increased metabolites in tumors relative to normal tissue [125,126]. Further, glutathione biosynthesis is required for tumor initiation and progression [113], and numerous oncogenic alterations promote glutathione biosynthesis by activating the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway [114,123,124]. Interestingly, despite being one of the most abundant metabolites in cancer cells, many cancer cells are resistant to inhibition of glutathione biosynthesis [113,127], indicative of functional redundancy in cellular antioxidant systems. However, targeting glutathione biosynthesis as part of combination therapy is effective in many circumstances [43,113,127], suggesting a potential role for the inhibition of NEAA utilization for glutathione biosynthesis as a therapeutic strategy.

2.8. 시스테인

황을 함유한 두 가지 단백질 구성 아미노산 중 하나인 시스테인은

반응성 티올 측쇄를 포함하여

다른 아미노산에서는 불가능한 여러 기능을 부여하는 독특한 특성을 가지고 있습니다.

예를 들어,

반응성 시스테인 잔기는 효소의 촉매 부위에서 효소 촉매 반응에서 핵ophile로 기능합니다 [103].

시스테인은

다른 시스테인과 디설파이드 결합을 형성하며,

이는 단백질 접힘과 안정성을 촉진하는 데 필수적입니다 [104].

반응성 시스테인 잔기는 항산화제가 활성 산소 종을 소거하는 능력의 주요 원동력입니다 [104,105]. 이러한 다양한 기능적 역할로 인해 시스테인은 암 연구에서 가장 많이 연구된 NEAA 중 하나입니다. 시스테인은 세린과 메티오닌으로부터 트랜스설파레이션 경로(그림 1)를 통해 신규 합성될 수 있습니다. 이 경로는 특정 조건 하에서 암 세포의 시스테인 생산에 기여한다는 것이 밝혀졌지만 [106,107,108], 세포 내 시스테인의 대부분은 세포 외 환경에서 시스테인 형태로 [109] 또는 산화 이량체 형태인 시스틴으로 흡수됩니다. 시스테인은 운반체 xCT를 통해 세포 내로 운반된 후 티오레독신 환원효소 1과 글루타티온 환원효소에 의해 시스테인으로 환원됩니다 [110]. 시스테인 흡수 과정은 암에서 중요한 역할을 하며, 이는 xCT를 암 치료의 잠재적 표적으로 억제하려는 수많은 시도에서 입증되었습니다 [111,112,113,114]. 흥미롭게도 시스테인 흡수 억제는 철분 의존성 세포 사멸인 페로프토시스[115]를 유도하며, 이 분자 구성 요소는 암 치료제로서의 잠재성을 평가받고 있습니다[116,117,118]. 혈장 시스테인과 시스테인의 효소적 고갈—아스파라긴에 대한 아스파라긴아제 접근법과 유사하게—도 종양 성장 억제에 효과적입니다[119]. 중요하게도, 시스테인 대사 조절의 주요 전사 조절인자—Keap1/Nrf2 경로—는 다양한 종양 유형에서 변이되어 있습니다 [120,121,122]이며, KRas 및 PI3K와 같은 종양 유발 신호 경로에 의해 활성화될 수 있습니다 [123,124], 이는 시스테인 대사 하류 조절이 중요한 종양 유발 기능임을 시사합니다.

앞서 언급된 바와 같이, 시스테인의 암에서의 주요 기능 중 하나는 여러 항산화 시스템의 일부로 활성산소 방어에 참여하는 것입니다 (그림 2) [105]. 이 리뷰에서 특히 중요한 것은 시스테인, 글루타메이트, 글리신이라는 세 가지 NEAA에서 합성되는 트리펩티드 항산화 물질인 글루타티온입니다 [56]. 글루타티온 대사 과정의 암에서의 잠재적 중요성은 정상 조직에 비해 종양에서 가장 크게 증가한 대사체 중 하나라는 관찰 결과에서 입증됩니다 [125,126]. 또한 글루타티온 생합성은 종양 발생 및 진행에 필수적이며 [113], 수많은 발암성 변이가 Keap1/Nrf2 경로를 활성화하여 글루타티온 생합성을 촉진합니다 [114,123,124]. 흥미롭게도, 암 세포에서 가장 풍부한 대사산물 중 하나임에도 불구하고 많은 암 세포는 글루타티온 생합성 억제에 저항성을 보입니다 [113,127], 이는 세포 내 항산화 시스템의 기능적 중복성을 시사합니다. 그러나 글루타티온 생합성을 표적으로 하는 조합 요법은 많은 경우 효과적입니다 [43,113,127], 이는 글루타티온 생합성에 사용되는 NEAA 이용 억제가 치료 전략으로의 잠재적 역할을 시사합니다.

2.9. Arginine

Arginine is a component of the urea cycle, a metabolic pathway that converts the toxic metabolic byproduct ammonia to urea to be excreted in urine (Figure 2). This process takes place primarily in the liver, and it has been observed that the urea cycle is suppressed in many tumors [128]. Mechanistically, suppression of the urea cycle in tumors is often accomplished through the epigenetic silencing of two urea cycle genes, ASS1 and ASL [129,130,131]. ASS1 and ASL suppression in tumors is believed to be beneficial for tumor growth because it diverts nitrogen into aspartate for pyrimidine biosynthesis [132]. While beneficial for promoting anabolic metabolism, the suppression of the urea cycle prevents these tumors from synthesizing arginine de novo, making them dependent on the uptake of arginine from the circulation (Figure 1) [133,134,135]. This makes these tumors sensitive to the enzymatic depletion of plasma arginine, an approach that has been explored in clinical trials as a therapeutic option [136,137,138,139]. Interestingly, while the elevated pyrimidine biosynthesis found in urea cycle-deficient tumors promotes proliferation, it also causes an imbalance in purine and pyrimidine nucleotide levels that leads to an increased mutational load [140]. This increased mutational load in turn increases the immunogenicity of these tumors and increases their responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitors [140]. Therefore, the alterations in arginine metabolism in cancer are an excellent example of how metabolic changes that support tumor growth can induce collateral vulnerabilities that can potentially be taken advantage of for cancer therapy.

2.9. 아르기닌

아르기닌은

독성 대사 부산물인 암모니아를 요산으로 전환하여

소변으로 배설하는 대사 경로인 요산 순환의 구성 요소입니다 (그림 2).

이 과정은 주로 간에서 발생하며,

많은 종양에서 요산 순환이 억제된다는 것이 관찰되었습니다 [128].

기전적으로, 종양에서의 요소 순환 억제는 주로 요소 순환 유전자인 ASS1과 ASL의 에피제네틱 침묵화를 통해 이루어집니다[129,130,131]. 종양에서의 ASS1 및 ASL 억제는 질소를 아스파르트산으로 전환하여 피리미딘 생합성에 활용하기 때문에 종양 성장에 유리한 것으로 추정됩니다 [132]. 그러나 이 과정은 아르기닌의 신생합성을 차단하여 종양이 순환계로부터 아르기닌을 흡수해야 하는 의존성을 유발합니다(그림 1) [133,134,135]. 이것은 이러한 종양이 혈장 아르기닌의 효소적 고갈에 민감하게 만들며, 이는 임상 시험에서 치료 옵션으로 탐구된 접근법입니다 [136,137,138,139]. 흥미롭게도, 요산 순환 결핍 종양에서 관찰되는 피리미딘 생합성 증가가 증식을 촉진하지만, 이는 푸린과 피리미딘 핵산 수치의 불균형을 초래하여 돌연변이 부하를 증가시킵니다 [140]. 이 증가된 돌연변이 부하는 다시 이 종양의 면역원성을 증가시키고 체크포인트 억제제에 대한 반응성을 높입니다 [140]. 따라서 암에서의 아르기닌 대사 변화는 종양 성장 지원을 통해 유발되는 대사 변화가 잠재적으로 암 치료에 활용될 수 있는 부수적 취약성을 유도하는 우수한 예시입니다.

2.10. Proline

Proline is unique among the proteinogenic amino acids for its cyclic shape, which allows for variability in protein structure. This is particularly important in proteins such as collagen, which contains a large amount of proline and is important for the structural elements of the extracellular matrix (Figure 2) [141]. Proline can be synthesized from glutamate through the action of P5C synthase and pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase and can be degraded by proline dehydrogenase (also known as proline oxidase) (Figure 1). Both the biosynthetic and degradation pathways for proline can be regulated by MYC, demonstrating that proline metabolism is also altered by oncogenic signaling pathways [142]. Interestingly, proline catabolism through proline dehydrogenase has been shown to promote cancer cell survival [143] and metastasis [144] but may also have a tumor-suppressive function [145]. These contrasting roles suggest a context-dependent role of proline metabolism in cancer. Proline metabolism in tumors is also important for bioenergetics, osmoregulation, stress protection, and control of apoptosis [146]. In addition to the biosynthetic pathway and uptake of proline, degradation of collagen in the extracellular matrix through macropinocytosis can provide an additional source of proline to pancreatic cancer cells under metabolic stress [147]. Despite these redundant sources of proline available to tumors, ribosome profiling studies have suggested that proline levels are limiting for protein synthesis in some tumors [148]. This suggests that targeting proline metabolism may be a viable therapeutic option for cancer treatment.

2.10. 프로린

프로린은 단백질 생성 아미노산 중 유일하게 순환 구조를 가지고 있어 단백질 구조의 다양성을 가능하게 합니다. 이는 콜라겐과 같은 단백질에서 특히 중요합니다. 콜라겐은 프로린을 다량 함유하며 세포외 기질의 구조적 요소(그림 2)에 중요합니다 [141]. 프로린은 글루타메이트로부터 P5C 합성효소와 피롤린-5-카르복실산 환원효소의 작용을 통해 합성될 수 있으며, 프로린 탈수소효소(프로린 산화효소로도 알려져 있음)에 의해 분해됩니다 (그림 1). 프로린의 생합성 및 분해 경로는 MYC에 의해 조절될 수 있으며, 이는 프로린 대사도 종양 유발 신호 경로에 의해 변화된다는 것을 보여줍니다 [142]. 흥미롭게도 프로린 탈수소효소를 통한 프로린 분해는 암 세포 생존 [143] 및 전이 [144]를 촉진하지만, 종양 억제 기능도 가질 수 있습니다 [145]. 이러한 상반된 역할은 암에서 프로린 대사의 맥락에 따른 역할을 시사합니다. 종양에서의 프로린 대사는 생체 에너지 대사, 삼투압 조절, 스트레스 보호, 세포 사멸 조절에도 중요합니다 [146]. 프로린의 생합성 경로와 흡수 외에도, 대사 스트레스 하에서 췌장암 세포는 세포외 기질의 콜라겐 분해를 통해 프로린의 추가 공급원을 얻을 수 있습니다 [147]. 이러한 프로린의 중복된 공급원에도 불구하고, 리보솜 프로파일링 연구는 일부 종양에서 단백질 합성에 있어 프로린 수준이 제한적임을 제시했습니다 [148]. 이는 프로린 대사 표적이 암 치료를 위한 유망한 치료 옵션이 될 수 있음을 시사합니다.

2.11. Tyrosine

Unlike the other NEAAs that reside in an interconnected network of metabolic pathways, tyrosine is synthesized from the EAA phenylalanine via phenylalanine hydroxylase (coded for by the PAH gene) (Figure 1). As mentioned, tyrosine is non-essential but can become essential in phenylketonuria, which is caused by mutations in the PAH gene [14]. While relatively little is known about the biology of tyrosine in cancer beyond its importance for protein synthesis, there have been efforts to take advantage of tyrosine metabolism in the clinic. For example, tyrosine-based PET imaging techniques have been developed and can be effective at imaging tumors and therapeutic responses [149,150,151]. It is believed that tyrosine PET tracers are effectively a readout of the activity of the amino acid transporter LAT1 [152,153], the expression and activity of which is elevated in numerous tumor types [154,155]. Interestingly, there is also a tyrosine-mimetic drug, SM-88, that is under development for the treatment of several cancer types and is in active clinical trials [156]. While details of SM-88 are limited, it will be interesting to see the results of these trials and learn more about this effort to target tyrosine metabolism for therapy.

2.11. 티로신

다른 NEAA와 달리 티로신은 상호 연결된 대사 경로 네트워크에 존재하지 않으며, 필수 아미노산(EAA)인 페닐알라닌으로부터 페닐알라닌 하이드록시라제(PAH 유전자에 의해编码)를 통해 합성됩니다(그림 1). 앞서 언급된 바와 같이 티로신은 비필수 아미노산이지만, PAH 유전자 변이로 인한 페닐케톤뇨증에서는 필수 아미노산으로 전환될 수 있습니다[14]. 티로신의 암 생물학에 대한 지식은 단백질 합성에서의 중요성을 넘어 상대적으로 제한적이지만, 티로신 대사 과정을 임상적으로 활용하려는 노력들이 진행 중입니다. 예를 들어, 티로신을 기반으로 한 PET 영상 기술이 개발되었으며, 종양 및 치료 반응을 영상화하는 데 효과적일 수 있습니다[149,150,151]. 티로신 PET 추적제는 아미노산 운반체 LAT1의 활성을 반영하는 지표로 여겨집니다[152,153], 이 운반체의 발현과 활성은 다양한 종양 유형에서 증가합니다[154,155]. 흥미롭게도 티로신을 모방한 약물 SM-88은 여러 암 유형의 치료를 위해 개발 중이며 현재 임상 시험이 진행 중입니다[156]. SM-88에 대한 세부 정보는 제한적이지만, 이 임상 시험 결과와 티로신 대사 표적 치료에 대한 이 노력의 추가 정보를 기대해 볼 수 있습니다.

3. Conclusions

Years of research have provided an increasingly clear picture of the diverse and important roles that NEAAs play in tumor metabolism. In addition to initial studies emphasizing the role of glutamine and glutamate metabolism in cancer, there is continually accumulating evidence that other NEAAs also play critical roles in the pathology of cancer. Importantly, several novel strategies to target NEAA metabolism are currently in clinical trials. In addition, dietary manipulation of NEAA metabolism is also a potentially effective strategy for inhibiting tumor growth that is being explored either as a primary treatment option or to enhance the efficacy of other chemotherapies. Importantly, the manipulation of dietary amino acid levels can have adverse effects on normal physiology [157], suggesting that strategies to manipulate dietary NEAAs will need to be developed carefully in order to avoid negative side effects. In addition, the inherent redundancy of NEAA metabolic pathways and the multiple sources of NEAAs available to cancer cells all combine to make targeting NEAA metabolism challenging. In the most successful examples of targeting NEAA metabolism for therapy, such as in ALL which lacks the ability to synthesize asparagine and is sensitive to asparaginase treatment, identifying circumstances where NEAA pathway redundancy is naturally limited can improve the likelihood of successfully targeting these pathways for therapy. As more NEAA-targeted therapies move towards the clinic, it will be exciting to observe the creative approaches that researchers develop to overcome these challenges.

3. 결론

수년간의 연구는 NEAAs가 종양 대사에서 다양하고 중요한 역할을 한다는 점을 점점 더 명확히 밝혀왔습니다. 글루타민과 글루타메이트 대사 과정의 역할을 강조한 초기 연구 외에도, 다른 NEAA들도 암 병리학에서 중요한 역할을 한다는 증거가 지속적으로 쌓이고 있습니다. 특히, NEAA 대사 과정을 표적으로 삼는 여러 새로운 전략이 현재 임상 시험 중입니다. 또한, NEAA 대사 과정을 식이 요법으로 조절하는 것은 종양 성장 억제를 위한 잠재적으로 효과적인 전략으로, 주요 치료 옵션으로 또는 다른 화학 요법의 효과를 강화하기 위해 탐구되고 있습니다. 중요하게도, 식이 아미노산 수준의 조작은 정상 생리학에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다[ NEAA 대사 경로를 표적화한 치료에서 가장 성공적인 사례 중 하나는 아스파라긴을 합성할 수 없고 아스파라긴아제 치료에 민감한 급성 림프구성 백혈병(ALL)입니다. NEAA 대사 경로의 중복성이 자연적으로 제한되는 상황을 식별하는 것은 이러한 경로를 표적화한 치료의 성공 가능성을 높일 수 있습니다. NEAA 표적 치료법이 임상 단계로 진전됨에 따라, 연구자들이 이러한 도전 과제를 극복하기 위해 개발할 창의적인 접근 방식이 기대됩니다.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Isaac S. Harris for comments on this review.

Funding

J.L.C. is supported by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Health under award K22 CA215828.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburg O., Wind F., Negelein E. The Metabolism of Tumors in the Body. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927;8:519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher J.W., Djulbegovic B., Soares H.P., Siegel B.A., Lowe V.J., Lyman G.H., Coleman R.E., Wahl R., Paschold J.C., Avril N., et al. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49:480–508. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle H. Nutrition needs of mammalian cells in tissue culture. Science. 1955;122:501–514. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3168.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunphy M.P.S., Harding J.J., Venneti S., Zhang H., Burnazi E.M., Bromberg J., Omuro A.M., Hsieh J.J., Mellinghoff I.K., Staton K., et al. In Vivo PET Assay of Tumor Glutamine Flux and Metabolism: In-Human Trial of (18)F-(2S,4R)-4-Fluoroglutamine. Radiology. 2018;287:667–675. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain M., Nilsson R., Sharma S., Madhusudhan N., Kitami T., Souza A.L., Kafri R., Kirschner M.W., Clish C.B., Mootha V.K. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science. 2012;336:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1218595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosios A.M., Hecht V.C., Danai L.V., Johnson M.O., Rathmell J.C., Steinhauser M.L., Manalis S.R., Vander Heiden M.G. Amino Acids Rather than Glucose Account for the Majority of Cell Mass in Proliferating Mammalian Cells. Dev. Cell. 2016;36:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Z., Vosseller K. O-GlcNAc in cancer biology. Amino Acids. 2013;45:719–733. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng M., Chen S., Lao T., Liang D., Sang N. Nitrogen anabolism underlies the importance of glutaminolysis in proliferating cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3921–3932. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.19.13139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zetterberg A., Engstrom W. Glutamine and the regulation of DNA replication and cell multiplication in fibroblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 1981;108:365–373. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeds P.J. Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J. Nutr. 2000;130:1835S–1840S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.7.1835S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borman A., Wood T.R., Black H.C., Anderson E.G., OESTEKLING M., Womack M., Rose W.C. The role of arginine in growth with some observations on the effects of argininic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1946;166:585–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Spronsen F.J., van Rijn M., Bekhof J., Koch R., Smit P.G. Phenylketonuria: Tyrosine supplementation in phenylalanine-restricted diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001;73:153–157. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantor J.R., Abu-Remaileh M., Kanarek N., Freinkman E., Gao X., Louissaint A., Jr., Lewis C.A., Sabatini D.M. Physiologic Medium Rewires Cellular Metabolism and Reveals Uric Acid as an Endogenous Inhibitor of UMP Synthase. Cell. 2017;169:258–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamphorst J.J., Nofal M., Commisso C., Hackett S.R., Lu W., Grabocka E., Vander Heiden M.G., Miller G., Drebin J.A., Bar-Sagi D., et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. 2015;75:544–553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan M., Reid M.A., Lowman X.H., Kulkarni R.P., Tran T.Q., Liu X., Yang Y., Hernandez-Davies J.E., Rosales K.K., Li H., et al. Regional glutamine deficiency in tumours promotes dedifferentiation through inhibition of histone demethylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:1090–1101. doi: 10.1038/ncb3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan M.R., Danai L.V., Lewis C.A., Chan S.H., Gui D.Y., Kunchok T., Dennstedt E.A., Vander Heiden M.G., Muir A. Quantification of microenvironmental metabolites in murine cancers reveals determinants of tumor nutrient availability. Elife. 2019;8:e44235. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan M.R., Mattaini K.R., Dennstedt E.A., Nguyen A.A., Sivanand S., Reilly M.F., Meeth K., Muir A., Darnell A.M., Bosenberg M.W., et al. Increased Serine Synthesis Provides an Advantage for Tumors Arising in Tissues Where Serine Levels Are Limiting. Cell Metab. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]