Nat Rev Cancer

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Jun 26.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Jul 29;16(10):619–634. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.71

From Krebs to Clinic: Glutamine Metabolism to Cancer Therapy

Brian J Altman 1,2,3, Zachary E Stine 1,2,3, Chi V Dang 1,2,3,#

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC5484415 NIHMSID: NIHMS866619 PMID: 27492215

The publisher's version of this article is available at Nat Rev Cancer

This article has been corrected. See Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Nov 11;16(12):773.

This article has been corrected. See Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Oct 14;16(11):749.

Abstract

The resurgence of research in cancer metabolism has recently broadened interests beyond glucose and the Warburg Effect to other nutrients including glutamine. Because oncogenic alterations of metabolism render cancer cells addicted to nutrients, pathways involved in glycolysis or glutaminolysis could be exploited for therapeutic purposes. In this Review, we provide an updated overview of glutamine metabolism and its involvement in tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo, and explore the recent potential applications of basic science discoveries in the clinical setting.

Introduction

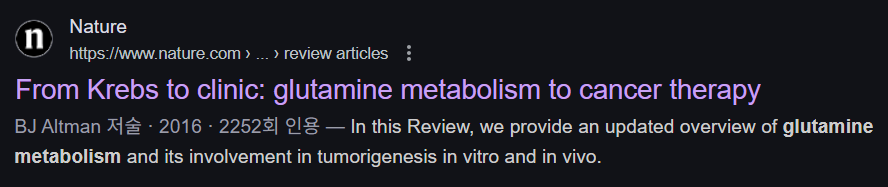

Glucose has been central to the study of cancer metabolism following Otto Warburg’s pioneering work on aerobic glycolysis 1, whereas studies of other nutrients, such as glutamine, have been at the margins of the cancer metabolism literature until recently. Hans Krebs, famed for characterization of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, studied glutamine metabolism in animals in 1935, and documented its importance in organismal homeostasis. Subsequently, the role of glutamine in cell growth and cancer cell biology was slowly appreciated (Figure 1 (Timeline)) and has been a subject of several comprehensive reviews 2, 3. Given the many energy-generating and biosynthetic roles glutamine plays in growing cells, which are discussed and updated in this Review, inhibition of glutaminolysis has the potential to effectively target cancer cells.

초록

암 대사 연구의 부활은

최근 글루코스 및 워버그 효과 beyond를 넘어

글루타민을 포함한 다른 영양소로 연구 범위를 확장시켰습니다.

암 유발성 대사 이상은

암 세포가 영양소에 의존하게 만들며, 글리코lysis 또는 글루타민olysis와 관련된 경로는

치료적 목적으로 활용될 수 있습니다.

이 리뷰에서는

글루타민 대사 및 체외 및 체내 종양 발생에서의 역할을

최신 동향과 함께 개괄적으로 소개하며,

기초 과학 발견의 임상적 적용 가능성을 탐구합니다.

소개

글루코스는

Otto Warburg의 호기성 글리코lysis에 대한 선구적인 연구 이후

암 대사 연구의 중심에 있었습니다 1,

반면 글루타민과 같은 다른 영양소에 대한 연구는

최근까지 암 대사 문헌의 주변부에 머물러 있었습니다.

Hans Krebs는

트리카르복실산(TCA) 사이클의 특성을 규명한 것으로 유명한 과학자로,

1935년 동물에서 글루타민 대사를 연구하고

그 중요성을 유기체 내 항상성 유지에 기여하는 것으로 기록했습니다.

이후 글루타민의 세포 성장 및 암 세포 생물학에서의 역할은

점차 인정받기 시작했으며(그림 1 (타임라인)),

여러 포괄적인 리뷰 논문에서 다루어졌습니다(2, 3).

성장 중인 세포에서 글루타민이 수행하는 에너지 생성 및 생합성 역할은

이 리뷰에서 논의되고 업데이트되었으며,

글루타미노lysis 억제는 암 세포를 효과적으로 표적화할 잠재력을 가지고 있습니다.

Figure 1.

Timeline of key discoveries in mammalian glutamine metabolism and cancer

α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase.

There are nine amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, valine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, histidine, threonine and lysine) humans cannot synthesize and hence are considered essential amino acids. Five amino acids (alanine, aspartate, asparagine, glutamate, and serine) are believed to be dispensable, because they can be readily synthesized. Glutamine belongs to a group of amino acids that are conditionally essential, particularly under catabolic stressed conditions such as the post-operative period, injury, or sepsis, where glutamine consumption by the kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and immune compartment rise dramatically 4. Cells of the intestinal mucosa are particularly dependent on glutamine, and they rapidly undergo necrosis after glutamine depletion 4. These observations mirror the dependence of growing cancer cells on glutamine 5, with some cancer cells dying rapidly if glutamine is deprived 6.

Circulating glutamine is the most abundant amino acid (~500 μM) 7, making up over 20% of the free amino acid pool in blood and 40% in muscle 8. While diet can serve as a source of glutamine from digested foods absorbed through the small intestine, the endothelium of which retains up to 30% of dietary glutamine, glutamine can be considered a non-essential amino acid at the organismal level owing to the fact that the muscle and other organs synthesize glutamine as a scavenger for ammonia produced from the metabolism of other amino acids 9. In fact, glutamine is held at a fairly constant level in the circulation, presumably due to de novo synthesis and release from the skeletal muscle, lung, and adipose tissue 3, 10, 11. The kidney releases ammonia from glutamine to maintain acid-base homeostasis 12, and the liver and kidney eliminate excess nitrogen in the form of urea from glutamine via the urea cycle, another process first identified by Krebs 13. In rapidly dividing cells such as lymphocytes, enterocytes of the small intestine, and especially cancer cells, glutamine is avidly consumed and utilized for both energy generation and as a source of carbon and nitrogen for biomass accumulation 14.

인간은

9가지 아미노산(이소류신, 류신, 메티오닌, 발린, 페닐알라닌, 트립토판, 히스티딘, 트레오닌, 라이신)을

체내에서 합성할 수 없기 때문에 필수 아미노산으로 분류됩니다.

5가지 아미노산(알라닌, 아스파르트산, 아스파라긴, 글루타메이트, 세린)은

체내에서 쉽게 합성될 수 있기 때문에 비필수 아미노산으로 간주됩니다.

글루타민은 조건부 필수 아미노산 그룹에 속하며,

특히 수술 후 기간, 외상, 패혈증과 같은 분해 스트레스 조건에서 신장, 소화관, 면역 체계에서

글루타민 소비가 급격히 증가합니다 4.

장 점막 세포는

글루타민에 특히 의존적이며,

글루타민 부족 시 빠르게 괴사합니다 4.

이러한 관찰 결과는

성장 중인 암 세포의 글루타민 의존성과 일치합니다 5,

일부 암 세포는

글루타민이 결핍되면 급속히 사멸합니다 6.

순환 글루타민은 가장 풍부한 아미노산 (~500 μM) 7로,

혈중 자유 아미노산 풀의 20% 이상을 차지하며

근육에서는 40%를 차지합니다 8.

식이 섭취를 통해 소장에서 흡수된 소화된 식품으로부터

글루타민의 공급원이 될 수 있지만,

소장 내피는 식이 글루타민의 최대 30%를 유지합니다.

그럼에도 불구하고

글루타민은 근육 및 기타 장기가 다른 아미노산의 대사 과정에서 생성되는 암모니아를 제거하기 위해

글루타민을 합성하기 때문에 유기체 수준에서는 필수 아미노산이 아닙니다 9.

실제로 글루타민은

순환계에서 비교적 일정한 수준으로 유지되며,

이는 골격근, 폐, 지방 조직에서의 신규 합성과 방출 때문으로 추정됩니다 3, 10, 11.

신장은

글루타민으로부터 암모니아를 방출하여 산-염기 균형을 유지하며 12,

간과 신장은 글루타민을 통해 요산 순환을 통해 과잉 질소를 요산 형태로 배설합니다.

이 과정은 Krebs에 의해 처음 발견된 과정입니다 13.

림프구, 소장 상피세포, 특히 암세포와 같은 빠르게 분열하는 세포에서는

글루타민이 에너지 생성 및 생물량 축적을 위한

탄소와 질소의 원천으로 활발히 소비되고 활용됩니다 14.

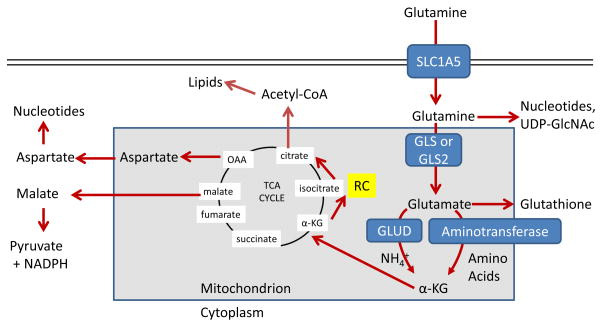

Glutamine Metabolism

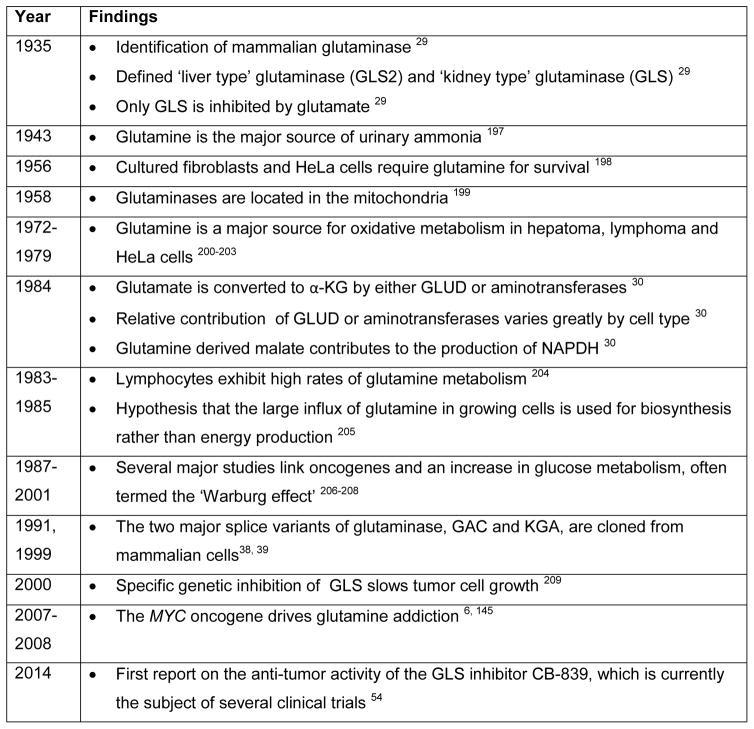

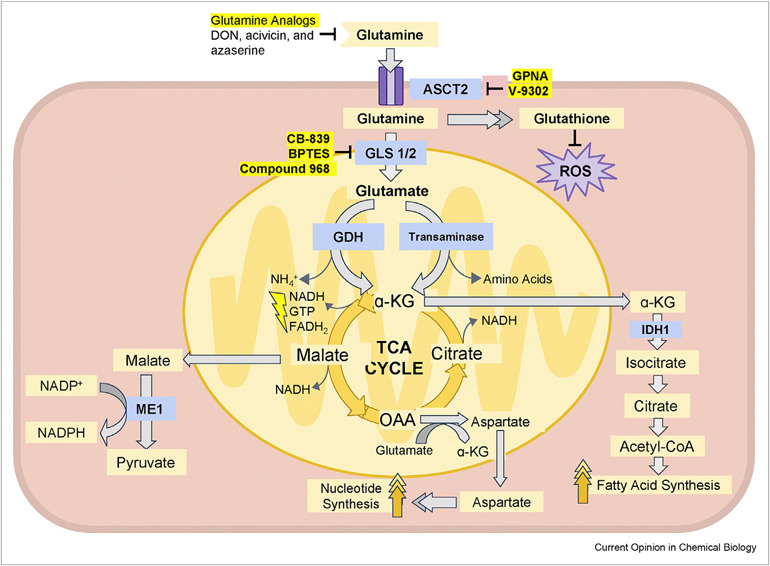

The maintenance of high levels of glutamine in the blood provides a ready source of carbon and nitrogen to support biosynthesis, energetics and cellular homeostasis that cancer cells may exploit to drive tumor growth. Glutamine is transported into cells through one of many transporters 15, such as the heavily-studied solute carrier family 1 neutral amino acid transporter member 5 (SLC1A5; also known as ASCT2; Figure 2) 16, and can then be used for biosynthesis or exported back out of the cell by antiporters in exchange for other amino acids such as leucine through the L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, a heterodimer of SLC7A5 and SLC3A2)) antiporter 17. Glutamine-derived glutamate can be also exchanged through the xCT (a heterodimer of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2; Figure 3) antiporter for cystine, which is quickly reduced to cysteine inside the cell18.

글루타민 대사

혈중 글루타민 수치를 높게 유지하는 것은

암 세포가 종양 성장에 활용할 수 있는

탄소와 질소의 안정적인 공급원을 제공하여

생합성, 에너지 대사 및 세포 내 균형 유지에 기여합니다.

글루타민은

여러 운반체 중 하나를 통해

세포 내로 운반됩니다.

예를 들어, 광범위하게 연구된 용질 운반체 가족 1 중성 아미노산 운반체 5(SLC1A5; ASCT2로도 알려져 있음; 그림 2) 16을 통해 운반되며, 이후 생합성에 사용되거나 다른 아미노산(예: 류신)과 교환하여 세포 밖으로 배출될 수 있습니다. 이 과정은 L-형 아미노산 운반체 1(LAT1) , SLC7A5와 SLC3A2의 이량체) 반수송체 17을 통해 다른 아미노산과 교환되어 세포 밖으로 배출될 수 있습니다. 글루타민에서 유래한 글루타메이트는 또한 xCT(SLC7A11과 SLC3A2의 이량체; 그림 3) 반수송체를 통해 시스테인과 교환될 수 있으며, 이는 세포 내부에 빠르게 시스테인으로 환원됩니다18.

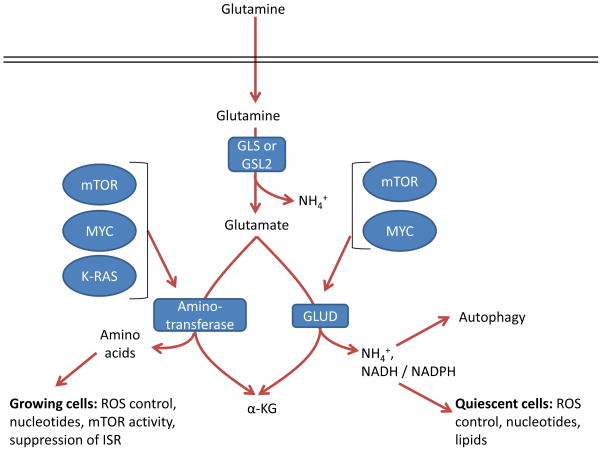

Figure 2. Major metabolic and biosynthetic fates of glutamine.

Glutamine enters the mammalian cell through transporters such as SLC1A5 (also known as ASCT2) 15. Glutamine itself can contribute to nucleotide biosynthesis and uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) synthesis for support of protein folding and trafficking 210, or is converted to glutamate by glutaminase (GLS or GLS2) 28. Glutamate can contribute to the synthesis of glutathione 110, and has many other metabolic fates in the cell that impact on several inborn errors of metabolism, which were recently reviewed 211. Glutamate is converted to α-ketoglutarate (αKG) through one of two sets of enzymes, glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1 or GLUD2, henceforth referred to collectively as GLUD) or aminotransferases 30. While the byproduct of GLUD is NH4+, the byproduct of aminotransferase reactions is other amino acids. Note that aminotransferases may be present either in the cytoplasm or the mitochondria. α-ketoglutarate enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and can provide energy for the cell. Malate exiting the TCA cycle can produce pyruvate and NADPH for reducing equivalents 31, and oxaloacetate (OAA) can be converted to aspartate to support nucleotide synthesis 34. These two pathways are illustrated in more detail in Figure 4. Alternately, α-KG can proceed backwards through the TCA cycle, in a process called reductive carboxylation (RC) to produce citrate, which supports synthesis of acetyl-CoA and lipids 87.

글루타민은

SLC1A5(ASCT2로도 알려져 있음)와 같은 운반체를 통해

포유류 세포로 들어갑니다. 15.

글루타민 자체는

단백질 접힘과 수송을 지원하기 위해 뉴클레오티드 생합성과

우리딘 이인산 N-아세틸글루코사민(UDP-GlcNAc) 합성에 기여할 수 있으며, 210

또는 글루타미나제(GLS 또는 GLS2)에 의해 글루타메이트로 전환됩니다. 28.

글루타메이트는

글루타티온 합성에 기여할 수 있으며 110,

세포 내 여러 대사 경로를 통해 여러 선천성 대사 장애에 영향을 미치는 다양한 대사 경로를 가집니다.

이는 최근에 검토되었습니다 211.

글루타메이트는

두 가지 효소 세트 중 하나를 통해

α-케토글루타레이트(αKG)로 전환됩니다.

이 효소 세트는 글루타메이트 탈수소효소(GLUD1 또는 GLUD2, 이하 GLUD로 통칭) 또는

아미노전달효소입니다 30.

GLUD의 부산물은 NH4+이며, 아미노트랜스퍼레이스 반응의 부산물은 다른 아미노산입니다. 아미노트랜스퍼레이스는 세포질이나 미토콘드리아에 존재할 수 있습니다. α-케토글루타레이트는 트리카르복실산(TCA) 회로에 들어가 세포에 에너지를 공급할 수 있습니다. TCA 회로에서 나가는 말레이트는 환원 등가물 31을 생성하기 위해 피루베이트와 NADPH를 생산할 수 있으며, 옥살아세테이트(OAA)는 뉴클레오티드 합성을 지원하기 위해 아스파르테이트로 전환될 수 있습니다 34. 이 두 경로는 그림 4에 더 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 대안으로, α-KG는 TCA 회로를 역방향으로 진행하는 환원적 카복실화(RC) 과정을 통해 시트르산을 생성할 수 있으며, 이는 아세틸-CoA와 지질 합성을 지원합니다 87.

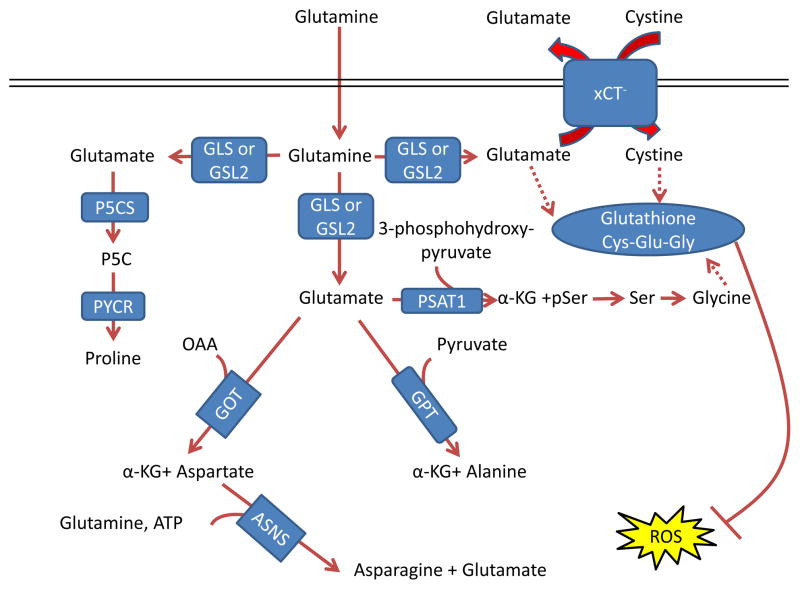

Figure 3. Glutamine control of amino acid pools and ROS.

Glutamate acts as a nitrogen donor for the transamination involved in the production of ‘dispensable amino acids’ alanine, aspartate, and serine through the actions of glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvate transaminase (GPT) and phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), respectively. Glutamine can also act as a nitrogen donor for asparagine through asparagine synthetase (ASNS). In a reaction independent of transamination, proline can be synthesized by conversion of glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C) by pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS; also known as aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family member A1, (ALDH18A1)) and subsequently to proline by pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1 (PYCR1) and PYCR2. Glutamine also contributes to the tripeptide glutathione (composed of glutamate, cysteine and glycine), which neutralizes the ROS H2O2 110. The first step in glutathione synthesis is the condensation of glutamate and cysteine through glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL; not shown in the figure). Glutamine input directly contributes to the availability of cysteine and glycine for production of glutathione. Glutamate can be exchanged for cystine (which is quickly reduced to cysteine inside the cell) through the xCT antiporter (a heterodimer of SLC7A11 and SCL3A2), which has been shown to be important in a variety of cancers and has been considered as a drug target 18, 212. Glycine is next added by glutathione synthetase (GSS; not shown in the figure). Additionally, glutamate can contribute to glycine through transamination by PSAT1 into phosphoserine (pSer) and α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and subsequent conversion to glycine through serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT; not shown in the figure) as part of the one-carbon metabolism pathway, which has been shown in numerous studies to be critical in cancer metabolism and is also reviewed in this Focus Issue by Dr. Karen Vousden 139, 140, 213. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; OAA, oxaloacetate.

글루타메이트는 글루타믹-옥살로아세틱 트랜스아미나제 (GOT), 글루타믹 피루vate 트랜스아미나제 (GPT) 및 인산세린 아미노트랜스퍼라제 1 (PSAT1)의 작용을 통해 '필수 아미노산'인 알라닌, 아스파르트산, 세린의 생성에 관여하는 트랜스아미네이션 과정에서 질소 공급원으로 작용합니다. 글루타민은 아스파라긴 합성효소(ASNS)를 통해 아스파라긴의 질소 공급원으로 작용할 수 있습니다. 트랜스아미네이션과 독립적인 반응에서, 글루타메이트는 피롤린-5-카르복시산(P5C)으로 전환되어 피롤린-5-카르복시산 합성효소(P5CS; 알데히드 탈수소효소 18 가족 구성원 A1, ALDH18A1로도 알려져 있음)에 의해 프로린으로 합성될 수 있습니다. 이후 피롤린-5-카르복실산 환원효소 1(PYCR1)과 PYCR2를 통해 프로린으로 전환됩니다. 글루타민은 글루타메이트, 시스테인, 글리신으로 구성된 트리펩티드 글루타티온(ROS인 H₂O₂를 중화함)의 합성에 기여합니다. 110. 글루타티온 합성의 첫 번째 단계는 글루타메이트와 시스테인의 축합 반응으로, 글루타메이트-시스테인 리가아제(GCL; 그림에 표시되지 않음)에 의해 촉매됩니다. 글루타민의 공급은 글루타티온 합성에 필요한 시스테인과 글리신의 가용성에 직접 기여합니다. 글루타메이트는 xCT 항포터(SLC7A11과 SCL3A2의 이량체)를 통해 시스테인(세포 내에서는 빠르게 시스테인으로 환원됨)과 교환될 수 있으며, 이는 다양한 암에서 중요하게 작용하며 약물 표적으로 고려되어 왔습니다 18, 212. 글리신은 다음으로 글루타티온 합성효소(GSS; 그림에 표시되지 않음)에 의해 추가됩니다. 또한 글루타메이트는 PSAT1에 의해 포스포세린(pSer)과 알파-케토글루타레이트(αKG)로 트랜스아미노화되고, 이후 세린 하이드록시메틸트랜스퍼레이즈(SHMT; 그림에 표시되지 않음)를 통해 글리신으로 전환되는 일탄소 대사 경로를 통해 글리신에 기여할 수 있습니다. 이 경로는 수많은 연구에서 암 대사에서 결정적 역할을 하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 이 특집号에서 Dr. Karen Vousden 139, 140, 213. GLS, 신장형 글루타미나제; GLS2, 간형 글루타미나제; GLUD, 글루타메이트 탈수소효소; OAA, 옥살아세트산.

In addition to transport, cancer cells can acquire glutamine through breaking down macromolecules under nutrient-deprived conditions. Macropinocytosis, which can play a role in normal biology and is active in most non-cancerous cells 19, can be stimulated by oncogenic RAS 20, allowing cancer cells to scavenge extracellular proteins, which are then degraded to amino acids including glutamine, supplying metabolites for survival 21, 22. This process must be tightly controlled 23, as excess RAS can hyperactivate macropinocytosis to lead to cell death, in a process previously misidentified as autophagic cell death 24. The complex relationship between glutamine metabolism and autophagy is discussed below, but it is notable that some RAS-transformed cancer cells derive glutamine and maintain metabolic flux from autophagic degradation of intracellular proteins 25, 26.

운반 외에도 암 세포는 영양 결핍 조건에서 대분자를 분해하여 글루타민을 획득할 수 있습니다. 정상 생물학에서 역할을 하며 대부분의 비암성 세포에서 활성인 마크로피노시토시스 19는 발암성 RAS에 의해 자극될 수 있으며, 이는 암 세포가 세포외 단백질을 흡수하여 글루타민을 포함한 아미노산으로 분해되어 생존에 필요한 대사물을 공급합니다 21, 22. 이 과정은 엄격하게 제어되어야 합니다 23, 과잉 RAS는 거대 세포 수용을 과도하게 활성화하여 세포 사멸로 이어질 수 있기 때문입니다. 이 과정은 이전에는 자가포식 세포 사멸로 잘못 인식되어 왔습니다 24. 글루타민 대사와 자가포식 사이의 복잡한 관계는 아래에서 설명하지만, 일부 RAS로 변형된 암세포는 세포 내 단백질의 자가포식 분해에서 글루타민을 추출하고 대사 흐름을 유지한다는 점이 주목할 만합니다 25, 26.

Energy generation

Upon entry into the cell via transporters, glutamine is converted by mitochondrial glutaminases to an ammonium ion and glutamate, which is further catabolized through two different pathways (Figure 2). Interestingly, despite its importance, the mitochondrial glutamine transporter has not yet been definitively identified and characterized 27. Glutaminase, which as Krebs determined exists in multiple tissue-specific versions, is encoded by two genes in mammals, kidney-type glutaminase (GLS) and liver-type glutaminase (GLS2) 28, 29. Glutamate can then be converted to α-ketoglutarate, which enters the TCA cycle to generate ATP through production of NADH and FADH2. As Lehninger first described 30, glutamate can be converted to α-ketoglutarate either by glutamate dehydrogenase (encoded by the highly-conserved and more broadly-expressed GLUD1 or the hominoid-specific GLUD2, henceforth collectively termed GLUD), which is an ammonia-releasing process, or by a number of non-ammonia producing aminotransferases, which transfer nitrogen from glutamate to produce another amino acid and α-ketoglutarate 30. Proliferating cells including cancer cells and activated lymphocytes utilize glutamine as an energy-generating substrate 31–33. In some tumor cells, a portion of metabolized glutamine is converted to pyruvate through the malic enzymes 31, 34, but as discussed below, this is likely not an energy-generating process. Notably, and as will be expanded on below, proliferating cells incorporate a majority of the glutamine they utilize for biomass for building protein and nucleotides 35.

에너지 생성

운반체를 통해 세포 내로 들어온 글루타민은

미토콘드리아 글루타민아제 의해 암모늄 이온과 글루타메이트로 전환되며,

이는 두 가지 다른 경로를 통해 추가적으로 분해됩니다 (그림 2).

흥미롭게도,

그 중요성에도 불구하고 미토콘드리아 글루타민 운반체는

아직 명확히 식별되거나 특성화되지 않았습니다 27.

크렙스가 여러 조직에 특정한 여러 버전이 존재한다고 밝힌 글루타미나아제는

포유류에서 신장형 글루타미나아제(GLS)와 간형 글루타미나아제(GLS2)라는 두 개의 유전자에 의해 암호화되어 있습니다 28, 29.

글루타메이트는 α-케토글루타레이트로 변환된 후 TCA 사이클로 들어가 NADH와 FADH2를 생성하여 ATP를 생성합니다. Lehninger가 처음 설명한 바와 같이 30, 글루타메이트는 암모니아를 방출하는 과정인 글루타메이트 탈수소효소(고도로 보존되고 더 광범위하게 발현되는 GLUD1 또는 호미노이드 특이적인 GLUD2에 의해 암호화되며, 이하 GLUD로 통칭함)에 의해, 또는 글루타메이트에서 질소를 전달하여 다른 아미노산과 α-케토글루타레이트를 생성하는 여러 비암모니아 생성 아미노전달효소에 의해 α-케토글루타레이트로 전환될 수 있습니다 이들은 글루타메이트로부터 질소를 전달하여 다른 아미노산과 α-케토글루타레이트를 생성합니다 30. 증식 중인 세포(암 세포 및 활성화된 림프구 포함)는 글루타민을 에너지 생성 기질로 활용합니다 31–33. 일부 종양 세포에서는 대사된 글루타민의 일부가 말산 효소에 의해 피루vate로 전환되지만, 아래에서 논의될 것처럼 이는 에너지 생성 과정이 아닙니다. 특히, 아래에서 자세히 설명될 것처럼 증식 세포는 이용하는 글루타민의 대부분을 단백질과 핵산 합성에 필요한 생물량으로 통합합니다 35.

Glutamine enzymes in cancer

The expression of enzymes involved in glutamine metabolism varies widely in cancers and is impacted by tissue of origin and oncogenotypes, which rewire glutamine metabolism for energy generation and stress suppression. Of the two glutaminase enzymes 28, GLS is more broadly expressed in normal tissue and thought to play a critical role in many cancers, while GLS2 expression is restricted primarily to the liver, brain, pituitary gland, and pancreas 36. Alternative splicing adds further complexity, as GLS pre-mRNA is spliced into either glutaminase C (GAC) or kidney-type glutaminase (KGA) isoforms 37–39. The two GLS isoforms and GLS2 also differ in their regulation and activity. GLS but not GLS2 is inhibited by its product glutamate, while GLS2 but not GLS is activated by its product ammonia in vitro 28, 29. Although both GLS and GLS2 are activated by inorganic phosphate, GLS (and particularly GAC) shows a much larger increase in catalysis in the presence of inorganic phosphate 37. Sirtuin 5 (SIRT5), which can be overexpressed in lung cancer 40, can desuccinylate GLS to suppress its enzymatic activity 41, while SIRT3 can deacetylate GLS2 to promote its increased activity with caloric restriction 42. Phosphate, acetyl-coA, and succinyl-CoA availability are impacted by nutrient uptake and metabolism, suggesting that GLS and GLS2 activity may be responsive to the metabolic state of the cell. Additionally, GLS is regulated through transcription 43, RNA-binding protein regulation of alternative splicing 44–47, post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs and pH stabilization of the GLS mRNA 48, 49, and protein degradation via the anaphase-promoting complex(APC)-CDH1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex 50, 51.

Expression of GAC, which is more active than KGA, is increased in several cancer types, suggesting that GLS alternative splicing may play an important role in the presumed higher glutaminolytic flux in cancer 18, 37, 45, 47, 52–54. In contrast, the role of GLS2 in cancer seems more complex. Silenced by promoter methylation in liver cancer, colorectal cancer and glioblastoma, re-expression of GLS2 has been shown to have tumor suppressor activities in colony formation assays 55–59. In fact, a recent studied showed that GLS2, in a non-metabolic function, sequesters the small GTPase RAC1 to suppress metastasis 60. However, GLS2 seems to support the growth and promote radiation resistance in some cancer types 61. Indeed, GLS2 is induced by the tumor suppressor p53 and related proteins p63 and p73 55, 56, 62, 63, suggesting perhaps that it functions in resistance to radiation, or is important in cancers that still possess wild-type p53. Additionally, GLS2 is a critical downstream target of the N-MYC oncogene in neuroblastoma 64, 65. The context dependent role of GLS2 in cancer clearly merits further study.

Once produced via glutaminase, glutamate is further converted to α-ketoglutarate through one of two mechanisms 30 (Figure 2). GLUD catalyzes the reversible deamination of glutamate to produce α-ketoglutarate and release ammonium. This reaction is at near-thermodynamic equilibrium in the liver, and so GLUD operates in both directions in this organ 66, but in cancer is thought to chiefly operate in the direction of α-ketoglutarate 67, and so GLUD activity will be discussed in this context for the purpose of this Review. Like GLS, GLUD is controlled through post-translational modifications and allosteric regulation. It is activated by ADP and inactivated by GTP, palmitoyl-CoA, and SIRT4-dependent ADP-ribosylation 68–71. Interestingly, GLUD is also allosterically activated by leucine, and mTOR (which itself is activated by leucine availability17, 72) can promote GLUD activity by suppressing SIRT4 expression 73, 74. These observations suggest that a low energetic state might induce GLUD allosterically via ADP to increase ATP production, while high leucine availability could also induce GLUD allosterically and through mTOR suppression of SIRT4.

Aminotransferases are enzymes which convert glutamate to α-ketoglutarate without producing ammonia (Figure 3). Two of these enzymes, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase are well known in clinical medicine as ‘liver enzymes’ or markers of liver pathology 75, 76. Glutamic-pyruvate transaminase (GPT, also known as alanine aminotransferase) transfers nitrogen from glutamate to pyruvate to make alanine and α-ketoglutarate, and is encoded in humans by GPT (cytoplasmic isoform) and GPT2 (mitochondrial isoform). Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT, also known as aspartate aminotransferase), which transfers nitrogen from glutamate to oxaloacetate to produce aspartate and α-ketoglutarate, is encoded for in humans by GOT1 (cytoplasmic isoform) and GOT2 (mitochondrial isoform). Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), as part of the serine biosynthesis pathway transfers nitrogen from glutamate to 3-phosphohydroxy-pyruvate to make phosphoserine and α-ketoglutarate. Different aminotransferases show different tissue distribution: aspartate aminotransferase activity is high across most tissues, while alanine aminotransferase activity is highest in the liver, although expression is still fairly universal 36, 77, 78. However, aminotransferases such as PSAT1 may be inappropriately expressed in tumors 79. The potential importance of which enzyme converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate in cancer cell physiology is discussed below.

암에서의 글루타민 효소

글루타민 대사 관련 효소의 발현은 암 유형에 따라 크게 다르며, 조직 기원 및 암 유전자형에 의해 영향을 받습니다. 이는 글루타민 대사를 에너지 생성 및 스트레스 억제를 위해 재편합니다. 두 가지 글루타민 분해 효소 28 중 GLS는 정상 조직에서 널리 발현되며 많은 암에서 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 반면 GLS2 발현은 주로 간, 뇌, 뇌하수체, 췌장에 제한됩니다 36. 대체 스플라이싱은 추가적인 복잡성을 더합니다. GLS 전사체는 글루타민아제 C(GAC) 또는 신장형 글루타민아제(KGA) 이소형으로 스플라이싱됩니다 37–39. 두 GLS 이소형과 GLS2는 조절 및 활성 측면에서도 차이가 있습니다. GLS는 그 제품인 글루타메이트에 의해 억제되지만, GLS2는 그 제품인 암모니아에 의해 활성화됩니다. 반면 GLS2는 암모니아에 의해 활성화되지 않습니다. 28, 29. GLS와 GLS2 모두 무기 인산염에 의해 활성화되지만, GLS(특히 GAC)는 무기 인산염 존재 시 촉매 활성이 훨씬 더 크게 증가합니다. 37. 폐암에서 과발현될 수 있는 Sirtuin 5 (SIRT5)는 GLS를 데수시닐화하여 그 효소 활성을 억제합니다 41, 반면 SIRT3는 칼로리 제한 시 GLS2를 데아세틸화하여 그 활성을 증가시킵니다 42. 인산염, 아세틸-CoA, 및 수신일-CoA의 가용성은 영양소 흡수 및 대사 과정에 의해 영향을 받으며, 이는 GLS 및 GLS2 활성이 세포의 대사 상태에 반응할 수 있음을 시사합니다. 또한 GLS는 전사 조절 43, RNA 결합 단백질에 의한 대안적 스플라이싱 조절 44–47, miRNA에 의한 전사 후 조절 및 GLS mRNA의 pH 안정화 48, 49, 그리고 anaphase-promoting complex(APC)-CDH1 E3 ubiquitin ligase 복합체를 통한 단백질 분해 50, 51을 통해 조절됩니다.

KGA보다 활성이 높은 GAC의 발현은 여러 암 유형에서 증가하며, 이는 암에서 추정되는 높은 글루타민 분해 흐름에 GLS 대안 스플라이싱이 중요한 역할을 할 수 있음을 시사합니다 18, 37, 45, 47, 52–54. 반면, GLS2의 암에서의 역할은 더 복잡해 보입니다. 간암, 대장암 및 뇌종양에서 프로모터 메틸화로 인해 침묵된 GLS2는 콜로니 형성 실험에서 종양 억제 활성을 나타내는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다 55–59. 실제로 최근 연구에서 GLS2는 대사 기능과 무관하게 소형 GTPase RAC1을 결합하여 전이를 억제하는 것으로 나타났습니다 60. 그러나 GLS2는 일부 암 유형에서 성장 지원을 촉진하고 방사선 저항성을 높이는 것으로 나타났습니다 61. 실제로 GLS2는 종양 억제인자 p53 및 관련 단백질 p63과 p73에 의해 유도됩니다 55, 56, 62, 63, 이는 방사선 저항성에 기능하거나 야생형 p53을 보유한 암에서 중요할 수 있음을 시사합니다. 또한 GLS2는 신경모세포종에서 N-MYC 종양 유전자의 중요한 하류 표적입니다 64, 65. GLS2의 암에서의 맥락에 따른 역할은 추가 연구가 분명히 필요합니다.

글루타미나아제를 통해 생성된 글루타메이트는 두 가지 메커니즘 중 하나를 통해 α-케토글루타레이트로 추가 전환됩니다 30 (그림 2). GLUD는 글루타메이트의 가역적 탈아미노화 반응을 촉매하여 α-케토글루타레이트를 생성하고 암모늄을 방출합니다. 이 반응은 간에서 열역학적 평형에 가깝게 유지되며, 따라서 GLUD는 이 기관에서 양방향으로 작동합니다 66. 그러나 암에서는 주로 α-케토글루타레이트 방향으로 작동하는 것으로 추정되며 67, 따라서 이 리뷰의 목적상 GLUD 활성은 이 맥락에서 논의될 것입니다. GLS와 마찬가지로 GLUD는 후전사적 변형과 알로스테릭 조절을 통해 조절됩니다. ADP에 의해 활성화되고 GTP, 팔미토일-CoA, 및 SIRT4에 의존하는 ADP-리보실화 68–71에 의해 비활성화됩니다. 흥미롭게도 GLUD는 류신에 의해 알로스테릭으로 활성화되며, 류신 가용성에 의해 활성화되는 mTOR(17, 72)는 SIRT4 발현을 억제함으로써 GLUD 활성을 촉진할 수 있습니다(73, 74). 이러한 관찰 결과는 저에너지 상태가 ADP를 통해 GLUD를 알로스테릭으로 활성화하여 ATP 생산을 증가시킬 수 있으며, 높은 류신 가용성은 GLUD를 알로스테릭으로 활성화하고 mTOR에 의한 SIRT4 억제를 통해 동일한 효과를 유발할 수 있음을 시사합니다.

아미노전달효소는 글루타메이트를 암모니아를 생성하지 않고 α-케토글루타레이트로 전환하는 효소입니다(그림 3). 이 중 알라닌 아미노전달효소와 아스파르트산 아미노전달효소는 임상 의학에서 '간 효소' 또는 간 병리의 지표로 잘 알려져 있습니다 75, 76. 글루타민-피루브산 트랜스아미나제(GPT, 알라닌 아미노트랜스퍼라아제라고도 함)는 글루타메이트에서 피루브산으로 질소를 전달하여 알라닌과 α-케토글루타르산을 생성하며, 인간에서는 GPT(세포질 이소형)와 GPT2(미토콘드리아 이소형)에 의해 암호화되어 있습니다. 글루타믹-옥살아세테이트 트랜스아미나제(GOT, 아스파르트산 아미노트랜스퍼라아제라고도 함)는 글루타메이트에서 옥살아세테이트로 질소를 전달하여 아스파르트산과 α-케토글루타르산을 생성하며, 인간에서는 GOT1(세포질 이소형)과 GOT2(미토콘드리아 이소형)에 의해 암호화되어 있습니다. 포스포세린 아미노전달효소 1(PSAT1)은 세린 생합성 경로의 일부로 글루타메이트에서 질소를 3-포스포히드록시피루베이트로 전달하여 포스포세린과 α-케토글루타레이트를 생성합니다. 다양한 아미노전달효소는 조직 분포가 다릅니다: 아스파르트산 아미노전달효소 활성은 대부분의 조직에서 높지만, 알라닌 아미노전달효소 활성은 간에서 가장 높으며, 표현은 여전히 널리 분포되어 있습니다 36, 77, 78. 그러나 PSAT1과 같은 아미노전달효소는 종양에서 부적절하게 표현될 수 있습니다 79. 글루타메이트를 α-케토글루타레이트로 전환하는 효소의 암 세포 생리학에서의 잠재적 중요성은 아래에서 논의됩니다.

Glutamine and ATP: What Else?Amino acid production

The nitrogen from glutamine supports the levels of many amino acid pools in the cell through the action of aminotransferases 35 (Figure 3). Separate from transamination reactions, carbon and nitrogen from glutamate can be used to produce proline, which plays a key role in the production of the extracellular matrix protein collagen 80 (Figure 3). While proline can be degraded to glutamate 81, the MYC oncoprotein can alter the expression of proline synthesis and degradation enzymes to promote the net synthesis of proline from glutamine-derived glutamate 82. Overall, tracer experiments determined that at least 50% of non-essential amino acids used in protein synthesis by cancer cells in vitro can be directly derived from glutamine 16, 83. While various glutamine-derived amino acids contribute to cancer cell survival, recent studies have shown that aspartate biosynthesis, which can depend on both glutamine flux through the TCA cycle and glutamate transamination 84, 85, is especially critical due its key role in both purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis to support cell division 84–86, as discussed in greater detail below.

글루타민과 ATP: 다른 것은 무엇인가? 아미노산 생산

글루타민의 질소는

아미노전달효소의 작용을 통해 세포 내 많은 아미노산 풀의 수준을 유지합니다 35 (그림 3).

트랜스아미노화 반응과 별개로,

글루타메이트의 탄소와 질소는

콜라겐과 같은 세포외 기질 단백질의 생산에 핵심 역할을 하는 프로린을 생성하는 데 사용될 수 있습니다 80 (그림 3).

프로린은

글루타메이트로 분해될 수 있지만 81,

MYC 종양 단백질은 프로린 합성 및 분해 효소의 발현을 조절하여

글루타민 유래 글루타메이트로부터 프로린의 순 합성을 촉진할 수 있습니다 82.

전체적으로 추적 실험을 통해

체외에서 암 세포가 단백질 합성에 사용하는 비필수 아미노산의 최소 50%가

글루타민으로부터 직접 유래될 수 있음을 확인했습니다 16, 83.

글루타민 유래 아미노산이 암 세포 생존에 기여하지만, 최근 연구에서는 글루타민의 TCA 회로 유입과 글루타메이트 트랜스아미노화 84, 85에 의존할 수 있는 아스파르테이트 생합성이 특히 중요합니다. 이는 푸린과 피리미딘 생합성에 핵심 역할을 하여 세포 분열을 지원하기 때문입니다 84–86, 아래에서 더 자세히 논의됩니다.

Reductive carboxylation and fatty acid synthesis

Cancer cells take up large amounts of glucose, but most of this carbon is excreted as lactate rather than metabolized in the TCA cycle 7, potentially depriving the cells of the citrate derived from the TCA cycle that supports fatty acid synthesis (Figure 2). Glutamine metabolism can serve as an alternative source of carbon to the TCA cycle to fuel fatty acid synthesis, through reductive carboxylation, which is a process by which glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate is reduced through the consumption of NADPH by isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDHs) in the non-canonical reverse reaction to form citrate 87. Reductive carboxylation, the importance of which is still somewhat controversial 88, seems to be a major source of carbon for lipid synthesis in cancer cells that are hypoxic, have constitutive hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIFα) stabilization or have mitochondrial defects 89–92. Although the contribution of reductive carboxylation to lipid formation from glutamine remains unclear due to the possibility of isotope exchange 88, studies suggest that reductive carboxylation occurs in vivo and can support lipogenesis for tumor growth and progression 89, 93, 94 and can also control the levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) 95.

환원적 카복실화 및 지방산 합성

암 세포는 대량의 포도당을 흡수하지만, 이 중 대부분은 TCA 회로에서 대사되지 않고 젖산으로 배출됩니다 7, 이는 TCA 회로에서 유래한 시트르산이 지방산 합성을 지원하는 데 필요한 탄소를 세포에 공급하지 못하게 할 수 있습니다 (그림 2). 글루타민 대사는 TCA 회로 대신 지방산 합성을 위한 탄소 공급원으로 작용할 수 있으며, 이는 글루타민에서 유래한 α-케토글루타르산이 이소시트르산 탈수소효소(IDHs)에 의해 NADPH를 소비하는 비정형 역반응을 통해 시트르산으로 환원되는 환원적 카복실화 과정을 통해 이루어집니다 87. 환원성 카복실화(그 중요성은 여전히 일부 논란의 여지가 있음 88)는 저산소 환경에 처한 암 세포, 구성적 저산소 유도 인자-α(HIFα) 안정화 또는 미토콘드리아 결함이 있는 세포에서 지방산 합성의 주요 탄소 공급원으로 작용하는 것으로 보입니다 89–92. 글루타민으로부터 지질 형성에 대한 환원성 카복실화의 기여도는 동위 원소 교환 가능성 88으로 인해 명확하지 않지만, 연구 결과 환원성 카복실화가 체내에서 발생하며 종양 성장 및 진행을 위한 지질 생성을 지원할 수 있으며 89, 93, 94 미토콘드리아 활성 산소 종(ROS) 수준을 조절할 수 있음을 제시합니다 95.

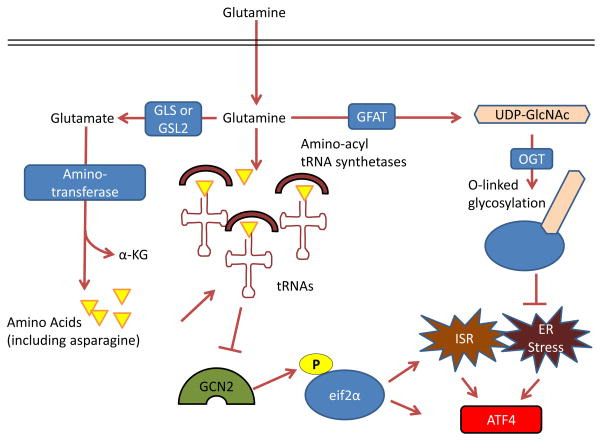

Protein synthesis, trafficking, and stress pathway suppression

Several of the metabolic fates of glutamine directly support protein synthesis and trafficking, and suppress stress responses carried out by two related pathways, the integrated stress response (ISR) and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway (Figure 4). Glutamine input thus supports the overall amino acids pools of the cell to suppress the ISR, which is otherwise activated under amino acid deprivation by the amino acid-sensing kinase GCN2 (encoded by EIF2αK4) (Figure 3). Phosphorylation of eIF2α by GCN2 inhibits general cap-dependent protein synthesis via the ISR but induces cap-independent synthesis of the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which in turn induces a pathway to increase transcription of ER-associated chaperones, halt cap-dependent translation, and eventually result in cell death 96. Glutamine deprivation can directly lead to uncharged tRNAs, or lead to a depletion of downstream products such as asparagine to indirectly lead to uncharged tRNAs, all of which can activate GCN2 and induce ATF4 translation. Suppression of the ISR by glutamine input has been shown to be critical for survival of several cancer cell and tumor types including neuroblastoma and breast cancer65, 97, 98. It was also observed that GCN2 is activated in mice in response to treatment with asparaginase99, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and may deplete serum asparagine and glutamine 100–102.

단백질 합성, 운반 및 스트레스 경로 억제

글루타민의 대사 경로 중 일부는 단백질 합성과 수송을 직접 지원하며, 통합 스트레스 반응(ISR)과 내소체(ER) 스트레스 경로라는 두 관련 경로를 통해 스트레스 반응을 억제합니다(그림 4). 따라서 글루타민의 공급은 세포의 전체 아미노산 풀을 지원하여, 아미노산이 결핍된 상황에서 아미노산 감지 키나아제 GCN2(EIF2αK4에 의해 암호화됨)에 의해 활성화되는 ISR을 억제합니다(그림 3). GCN2에 의한 eIF2α의 인산화는 ISR을 통해 일반적인 캡 의존적 단백질 합성을 억제하지만, 활성화 전사 인자 4(ATF4)의 캡 독립적 합성을 유도합니다. 이는 다시 내소체 관련 분자 샤페론의 전사 증가, 캡 의존적 번역 중단, 최종적으로 세포 사멸로 이어지는 경로를 활성화합니다 96. 글루타민 결핍은 직접적으로 충전되지 않은 tRNA를 유발하거나, 아스파라긴과 같은 하류 제품의 고갈을 통해 간접적으로 충전되지 않은 tRNA를 유발할 수 있으며, 이 모든 과정은 GCN2를 활성화하고 ATF4 번역을 유도합니다. 글루타민 공급을 통해 ISR을 억제하는 것은 신경모세포종과 유방암을 포함한 여러 암 세포 및 종양 유형의 생존에 필수적임이 입증되었습니다65, 97, 98. 또한, 미국 식품의약국(FDA)에서 급성 림프구성 백혈병(ALL) 치료에 승인된 아스파라긴아제 치료에 반응하여 쥐에서 GCN2가 활성화되는 것이 관찰되었습니다99. 이 약물은 혈청 아스파라긴과 글루타민을 고갈시킬 수 있습니다 100–102.

Figure 4. Control by glutamine of the integrated stress response, protein folding and trafficking, and ER stress.

GCN2, a serine-threonine kinase with a regulatory domain that is structurally similar to histidine-tRNA synthetase, is allosterically activated by uncharged tRNAs with amino acid deprivation (including glutamine deprivation) and in turn activates the integrated stress response (ISR) 96, 214, 215. Glutamine can suppress GCN2 activation through its contribution to amino acid pools by aminotransferases 65, 97–99. To control endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis, glutamine supports protein folding and trafficking through its contribution to uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) as part of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway. Glutamine is the substrate for glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT), which is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the hexosamine pathway, and the downstream product UDP-GlcNAc is a substrate for O-linked glycosylation through O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT). Thus, glutamine deprivation can lead to improper protein folding and chaperoning and ER stress 210. A key output of both the ISR and of ER stress is activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which is induced via cap-independent translation downstream of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation by GCN2 or other kinases 96. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase.

Glutamine also contributes to the synthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) as part of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, which is required for glycosylation, proper ER-Golgi trafficking, and suppression of the ER stress pathway, also upstream of ATF4 induction (Figure 4). Aberrant expression and activity of O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT), which links UDP-GlcNAc to proteins, was shown to be critical for the survival and progression of breast cancer, prostate cancer, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia103–105. Thus, glutamine input directly maintains translation, protein trafficking, and survival through suppression of the ISR and ER stress pathways106, 107.

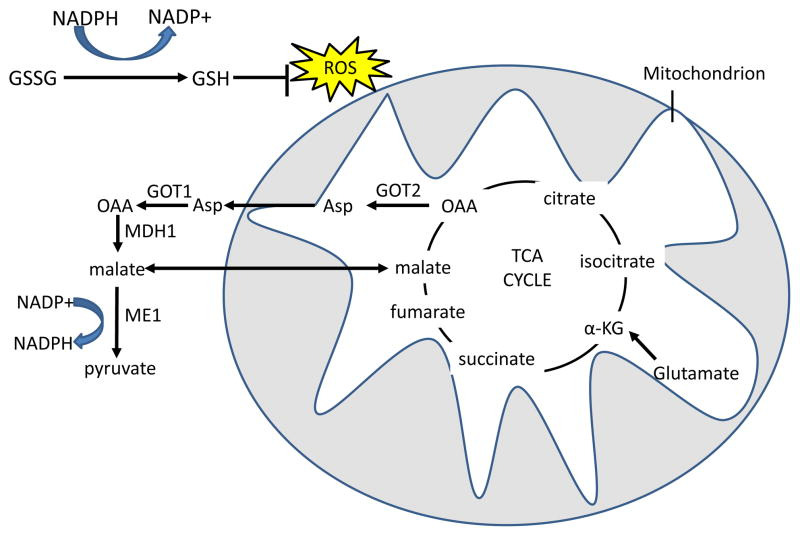

ROS control: glutathione and reducing equivalents

ROS-mediated cell signaling can be pro-tumorigenic when at physiological levels108, but when levels are in excess, ROS can be highly damaging to macromolecules 109. ROS are generated from several sources, including the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which can leak electrons to oxygen to generate superoxide (O2−). Thus, increased glutamine oxidation can correlate with increased ROS production108. However, several glutamine metabolic pathways lead to products that directly control ROS levels; hence, glutamine metabolism is critical for cellular ROS homeostasis. The most well-known pathway in which glutamine controls ROS is through synthesis of glutathione. Glutathione is a tri-peptide (Glu-Cys-Gly) which serves to neutralize peroxide free radicals. It has long been appreciated that glutamine input is the rate-limiting step for glutathione synthesis 110, and as shown in Figure 3, glutamine is directly and indirectly responsible for the other two amino-acid components of glutathione. As glutathione levels are known to correlate with tumorigenesis and drug resistance in cancer 111, a richer understanding of this pathway may contribute to better cancer treatment strategies. In fact, several studies have shown that acute glutamine administration to cancer patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy reduces treatment toxicity through increased glutathione synthesis 112, 113. Glutamine also affects ROS homeostasis through production of NADPH via GLUD114, and at least two other related mechanisms 31, 34 where TCA cycle-derived aspartate or malate is exported to the cytoplasm and then converted to pyruvate to produce NADPH through the malic enzymes, provide reducing equivalents for glutathione. Figure 5 details two glutamine-derived pathways, one of which is mediated by oncogenic K-RAS 34.

Figure 5. Glutamine derived TCA cycle intermediates can be used via two pathways to produce NADPH and neutralize ROS through the malic enzyme.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) neutralizes H2O2 with the glutathione peroxidase enzyme, and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) is reduced by NADPH and glutathione reductase to regenerate GSH. In the first pathway, glutamine-derived malate is transported out of the mitochondria, and is converted by malic enzyme 1 (ME1) to pyruvate, reducing one molecule of NADP+ to NADPH. In the malate-aspartate shuttle-related second pathway, found in mutant KRAS-transformed cells, aspartate that is produced from GOT2 mediated transamination of glutamine-derived oxaloacetate (OAA) is transported out of the mitochondria. Aspartate is then converted in the cytosol back to OAA by GOT1 and then to malate by malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH1), which is in turn processed to pyruvate by ME1 to produce one molecule of NADPH 34. The fate of glutamine-derived pyruvate is similar to glucose-derived pyruvate in that much of it is expelled as lactate31. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetate transaminase.

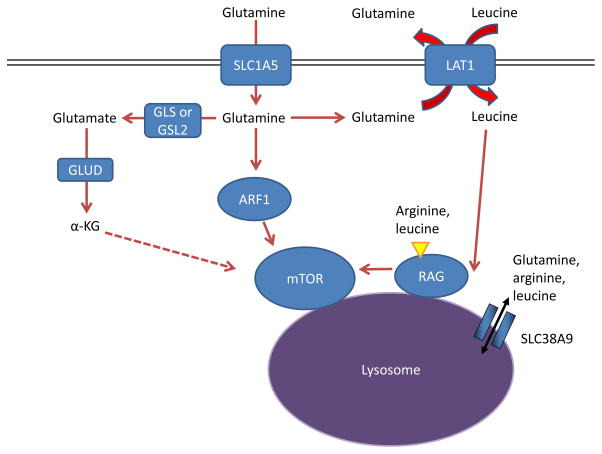

Regulation of mTOR

The TOR pathway senses amino acids and broadly promotes biosynthetic pathways such as protein translation and fatty acid synthesis while inhibiting degradative processes like autophagy 115. As such, mTOR activity must be tightly controlled to prevent inappropriate cell growth, and glutamine regulates this activity through several mechanisms (Figure 6). Amino acid availability stimulates mTOR activity independently of the activating mTOR pathway mutations often found in human cancer 115, and thus must be maintained regardless of mutation state. Glutamine and other amino acids that support mTOR activity need not come from amino acid transporters, as macropinocytosis-derived amino acids can also support mTOR activation 23. Conversely, mTOR itself can regulate glutamine metabolism by cell-type specific mechanisms, either by inhibiting expression of mitochondrial SIRT4, thereby relieving repression of GLUD69, 73, 116, or by instead inhibiting GLUD expression while upregulating expression of aminotransferases 117, as is discussed further below. The important implication of these findings is that, independent of direct mutations of negative regulators of the mTOR pathway itself, such as tuberous sclerosis 1 protein (TSC1; also known as hamartin) and TSC2 (also known as tuberin), increased glutamine uptake and metabolism that is common in many cancers may also strongly stimulate mTOR activity. The regulation of mTOR by amino acid availability, including glutamine, is a rich and evolving field, and more advances will be needed to fully understand this intriguingly intricate process 115.

Figure 6. Glutamine controls mTOR activity.

Amino acids stimulate the mTOR pathway, and amino acid pools rely on glutamine to be maintained. Specifically, arginine and leucine are two amino acids that can together almost fully stimulate mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) through activation of the RAS-related GTPase (RAG) complex, which in turn recruits mTORC1 to the lysosome and stimulates its activity 72, 133, 216. Glutamine can contribute to mTORC1 activation by being exchanged for essential amino acids, including leucine, through the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; a heterodimer of SLC7A5 and SLC3A2) transporter 17. This RAG-dependent regulation of mTOR is likely dependent on the lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9, which transports glutamine, arginine, and leucine as substrates129, 132, 133, as well as the leucine sensor sestrin 2 (not shown in Figure) 217, 218. Although the mechanism is not well understood, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) may regulate RAGB activity and mTOR activation downstream of glutamine metabolism 219. Several RAG-independent pathways of mTOR regulation by glutamine have also been identified. Glutamine promotes mTOR localization to the lysosome (and thus activity) through the RAS-family member ADP ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1) in a poorly understood mechanism, as well as the TTT-RUVBL1/2 complex (not shown in Figure) 128, 130. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase.

Nucleotide biosynthesis

Glutamine directly supports the biosynthetic needs for cell growth and division. While carbon from glutamine is used for amino acid and fatty acid synthesis, nitrogen from glutamine contributes directly to both de novo purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis 118. The importance of glutamine as a nitrogen reservoir is underscored by the fact that glutamine-deprived cancer cells undergo cell cycle arrest that cannot be rescued by TCA-cycle intermediates such as oxaloacetate but can be rescued by exogenous nucleotides 118, 119. In fact, synthesis of nucleotides from exogenous glutamine has been observed in human primary lung cancer samples cultured ex vivo 120.

Glutamine can also contribute to nucleotide biosynthesis through other pathways. Aspartate derived from glutamine via the TCA cycle and transamination (Figures 2,3) serves as a crucial source of carbon for purine and pyrimidine synthesis 84, 85, and provision of aspartate can rescue cell cycle arrest caused by glutamine deprivation 86. Additionally, glutamine dependent mTOR signaling may activate the enzyme carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamylase, and dihydroorotase (CAD), which catalyzes the incorporation of glutamine derived nitrogen into pyrimidine precursors 118, 121, 122. It has been suggested that NADPH produced downstream of glutamine metabolism and flux through the malic enzymes can further support nucleotide synthesis 31. Overall, glutamine can support biomass accumulation of fatty acids, amino acids, and nucleotides, by directly contributing carbon and nitrogen, indirectly generating reducing equivalents, and stimulating the signaling pathways that are necessary for their synthesis.

Autophagy and glutamine

Autophagy and glutamine have a complex relationship that mirrors the complexities of autophagy in cancer initiation and progression. The role of autophagy in cancer appears paradoxical: in some settings, it is tumor suppressive, by limiting oxidative stress and chromosomal instability that may lead to oncogenic mutations 123, 124, while in other situations, autophagy supports cancer cell survival by providing nutrients and suppressing stress pathways such as p53 125, 126. Thus, autophagy may influence tumor initiation and tumor progression differently, affecting tumor growth in a seemingly contradictory context-dependent manner. Many of the processes impacted by glutamine metabolism suppress autophagy. Glutamine suppresses GCN2 activation and the ISR, which can both otherwise induce autophagy 65, 97, 127. Glutamine also indirectly stimulates mTOR, which in turn suppresses autophagy through a complex mechanism17, 128–134 (recently reviewed by Dunlop and Tee 135). Similarly, ROS can induce autophagy as a stress response 136 but is suppressed by glutamine metabolism through production of glutathione and NADPH 31, 34, 110. Conversely, generation of ammonia from glutaminolysis could potentially promote autophagy activation in an autocrine and paracrine manner 137, 138. Although increased glutamine metabolism in cancer would suppress ROS levels (through glutathione production) as well as ER stress and promote mTOR activity, ammonia release from glutamine metabolism will vary between cancer types. Glutaminase releases ammonia in catalyzing the reaction of glutamine to glutamate, and some cancers process glutamate to α-ketoglutarate via GLUD (releasing another ammonium ion), while others use transamination, which does not release ammonia, as was first described by Lehninger 30. Similarly, SIRT5 desuccinylates and reduces GLS activity, thus reducing ammonia production and autophagy activation 41. Through the relative contributions of SIRT5 and GLUD versus transamination, one might speculate that ammonia production downstream of glutamine metabolism could ‘tune’ autophagy to the specific needs of the tumor cells to maintain organelle turnover, provide nutrients, and reduce cell stress.

자가포식 및 글루타민

자가포식과 글루타민은

암의 발병 및 진행에서 자가포식의 복잡성을 반영하는 복잡한 관계를 가지고 있습니다.

암에서 자가포식의 역할은 역설적으로 보입니다.

일부 환경에서는

종양 유발 돌연변이로 이어질 수 있는 산화 스트레스와 염색체 불안정성을 제한하여

다른 환경에서는 영양분을 공급하고 p53과 같은 스트레스 경로를 억제하여

따라서,

자가포식은 종양 발병과 종양 진행에 서로 다른 영향을 미치며,

겉으로는 모순된 상황 의존적인 방식으로 종양 성장에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

글루타민 대사에 의해 영향을 받는 많은 과정은 자가포식을 억제합니다.

글루타민은

GCN2 활성화와 ISR을 억제하며,

이 두 가지 모두 자가포식을 유도할 수 있습니다 65, 97, 127.

글루타민은

또한 간접적으로 mTOR를 자극하며,

이는 복잡한 메커니즘을 통해 자가포식을 억제합니다17, 128–134 (최근 Dunlop 및 Tee에 의해 검토됨135).

마찬가지로,

ROS는 스트레스 반응으로 자가포식을 유도할 수 있지만136,

글루타티온 및 NADPH의 생성을 통해 글루타민 대사에 의해 억제됩니다31, 34, 110.

반대로,

글루타민 분해에서 생성된 암모니아는

자크린 및 파라크린 방식으로 자가포식 활성화를 촉진할 가능성이 있습니다 137, 138.

암에서 글루타민 대사가 증가하면

글루타티온 생성을 통해 ROS 수준과 ER 스트레스를 억제하고 mTOR 활성을 촉진하지만,

글루타민 대사에서 암모니아 방출은 암 유형에 따라 달라집니다.

글루타미나제는 글루타민을 글루타메이트로 전환하는 반응을 촉매하며,

일부 암은 GLUD를 통해 글루타메이트를 α-케토글루타레이트로 전환(또 다른 암모늄 이온을 방출)하지만,

다른 암은 암모니아를 방출하지 않는 트랜스아미네이션을 사용합니다.

이는 Lehninger에 의해 처음 설명되었습니다 30.

마찬가지로,

SIRT5는 GLS를 탈수소화하고 GLS 활성을 감소시켜

암모니아 생성과 자가포식 활성화를 감소시킵니다 41.

SIRT5와 GLUD가 트랜스아미네이션에 비해 상대적으로 기여하는 정도를 통해,

글루타민 대사의 하류에 있는 암모니아 생성이 종양 세포의 특정 요구에 따라

자가포식을 '조정'하여 세포 기관의 재생을 유지하고, 영양분을 공급하며,

세포 스트레스를 감소시킬 수 있다고 추측할 수 있습니다.

Divergent Paths to α-Ketoglutarate

A perhaps understudied aspect of glutamine metabolism in cancer is the consequence of two divergent pathways that convert glutamate to α-ketoglutarate, and the subsequent fate of the nitrogen derived from glutamate (Figure 7). The different pathways were first identified more than thirty years ago 30, and the field has made much progress on the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of GLUD versus aminotransferase utilization, but not nearly as much progress on the ‘when’ or the ‘why’. Specifically, the field must still address the relative contributions of each pathway to cancer cell physiology, and how the two different pathways are utilized depending on tissue of origin, proliferation state, cell health or stress, stage of tumor evolution, and oncogenotype.

Figure 7. Two roads to α-ketoglutarate.

Glutamate can be converted by one of two different pathways into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), and the choice of which pathway is influenced both by oncogene input and cell proliferation and metabolic state. GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; ISR, integrated stress response; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Reactions via GLUD or aminotransferases result in production of α-ketoglutarate but have different by-products. In addition to α-ketoglutarate and ammonium, GLUD can produce both NADH and NADPH with different kinetics 114, which support the TCA cycle, bioenergetics, control of ROS levels, and lipid synthesis. In contrast, the byproduct of aminotransferases is α-ketoglutarate as well as other amino acids such as serine, alanine, aspartate, and asparagine downstream of aspartate, which contribute to a variety of cell functions such as nucleotide biosynthesis, redox control, and suppression of the ISR 65, 84, 85, 97, 98, 139–141. In breast cancer with genomic amplification of the serine biosynthesis gene phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), PSAT1 is the major source of glutamine dependent α-ketoglutarate, through transamination,, and breast cancer cells with amplified PHGDH grow poorly after PHGDH depletion compared to those with normal levels 142, underscoring the importance of these reactions in certain tumor types. Alanine is a product of transamination that is highly secreted from some tumor types 30, 141, which perhaps may safely dispose of nitrogen without ammonia production. While some tumors are sensitive to the aminotransferase inhibitor aminooxyacetate (AOA) 65, 143, it is a broad-spectrum inhibitor, and so specific inhibition of individual aminotransferases will be required to assess their specific roles in cancer.

The underlying oncogenotype affects these two pathways differentially, which may be related to the metabolic requirements the oncogenes impose on the cells. MYC upregulates both GLUD and aminotransferases 144, and seems to require both pathways, depending on context 67, 145. In contrast, oncogenic mutant KRAS activity increases aminotransferases and decreases GLUD mRNA expression 34. The role of mTOR in glutamine metabolism seems highly context and cell-type specific: in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) and colon and prostate cancer cells, mTOR supports increased activity of GLUD via repression of SIRT4 69, 73, 116, whereas in mouse mammary 3D culture models and human breast cancer, mTOR instead inhibits expression of GLUD while promoting expression of aminotransferases, particularly PSAT1 117. It is notable that mTOR requires constant amino acid input 146, while KRAS drives macropinocytosis 22, and thus, pathway selection of glutamine catabolism by these two pathways may reflect differing metabolic requirements that we do not yet fully appreciate. Nonetheless, these studies do suggest that transformed cells with strong PI3K-AKT-mTOR, KRAS, or MYC pathway activation increase their flux of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate for metabolism and biosynthesis.

Some key differences in the two pathways from glutamate to α-ketoglutarate may warrant further studies. Most noticeably, in addition to ammonia release by GLS, GLUD releases an additional ammonium ion and transamination does not. While ammonia is often thought of as a toxic byproduct, cancers can utilize ammonia to induce autophagy and neutralize intracellular pH 137, 138, 147, and GLUD can also produce NADPH 114 to reduce glutathione and lead to lower levels ROS 114. Together, these pathways could reduce cell stress and promote survival in some cancers 148. GLUD catalyzes a reaction that is reversible; however, the high Km for ammonia limits this reaction to deamination of glutamate in most tissues with the exception of the liver 66, 149. In contrast, aminotransferases are freely reversible, and thus may provide more metabolic plasticity to certain cancer cells that rely on them. Further, GLUD results in disposal of a nitrogen atom in ammonium, while aminotransferase supports a much more biosynthetic phenotype that may better support rapidly growing cancer cells. In fact, a recent study suggests that rapidly-dividing mammary epithelial cells in culture as well as highly proliferative human breast cancers upregulate aminotransferases and downregulate GLUD expression 117. The authors show that growing cells incorporate the nitrogen from glutamine into non-essential amino acids for cell growth, whereas this nitrogen would otherwise be disposed of by GLUD activity 117. This further suggests that the utilized pathway from glutamate to α-ketoglutarate is highly dependent on the metabolic, biosynthetic, and stress-reduction needs of the cell.

Oncogenes and Glutamine Metabolism

Glutamine metabolism is upregulated by many oncogenic insults and mutations (Table 1). This section highlights and expands on some of these. The MYC oncogene has perhaps been most associated with upregulated glutamine metabolism. MYC is the third most commonly amplified gene in human cancer 150, and the discovery that MYC-transformed cells become dependent on exogenous glutamine helped to drive a resurgence in the interest in glutamine metabolism 6, 31. MYC was found to upregulate glutamine transporters and induce the expression of GLS at the mRNA and protein level 48, 145, and to drive a glutamine-fueled TCA cycle and glutathione production in hypoxia 151. Glutamine in MYC-driven cells can be used for de novo proline synthesis 82 or production of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate in breast cancer152, although the latter finding has not been independently corroborated. Infection by adenovirus or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) both increase MYC expression and glutamine metabolism153, 154, and in the case of KSHV this may be a part of early tumorigenesis that eventually leads to Kaposi’s sarcoma. MYC can also mediate the reprogramming of glutamine metabolism downstream of activation of other oncogenic pathways, including mTOR 155, and crosstalk with HER2 (also known as ERBB2) and the estrogen receptor (ER) in breast cancer 156. All these findings support the notion that glutaminolysis is a major component of MYC-driven oncogenesis in most settings.

Table 1.

Influence of oncogenes and tumor suppressor gene loss on glutamine metabolism

Oncogenic changeRole in glutamine metabolism

| MYC upregulation | Upregulates glutamine metabolism enzymes and transporters 6, 31, 48, 145, 177 |

| KRAS mutations | Drives dependence on glutamine metabolism, suppresses GLUD, and drives NADPH via malic enzyme 1 (ME1) 34, 108, 119, 157, 158 |

| HIF1α or HIF2α stabilization | Drives reductive carboxylation of glutamine to citrate for lipid production 89–91 |

| HER2 upregulation | Activates glutamine metabolism through MYC and NF-κB 156, 220 |

| p53, p63, or p73 activity | Activates GLS2 expression 55, 56, 62, 63 |

| JAK2-V617F mutation | Activates GLS and increases glutamine metabolism 221 |

| mTOR upregulation | Promotes glutamine metabolism via induction of MYC155 and GLUD 69, 73 or aminotransferases 117 |

| NRF2 activation | Promotes production of glutathione from glutamine 222 |

| TGFβ-WNT upregulation | Promotes SNAIL and DLX2 activation, which upregulate GLS and activates epithelial-mesenchymal transition 183 |

| PKC zeta loss | Stimulates glutamine metabolism through serine synthesis 223 |

| PTEN loss | Decreased GLS ubiquitination 224 |

| RB1 loss | Upregulates GLS and SLC1A5 expression 225 |

GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLS2, liver-type glutaminase; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; ME1, malic enzyme 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NRF2, nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, like 2; PKCζ, protein kinase Cζ; RB1, retinoblastoma 1; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β.

Oncogenic KRAS-driven transformation induces dependence on glutamine metabolism 108, 119, 157. However, different KRAS mutations can have different effects; for instance, lung cancer cells harboring a KRAS-G12V mutation were much less glutamine dependent than those harboring G12C or G12D mutations, though the reasons for this were not clear 158. In addition to inducing dependence on glutamine driven nucleotide metabolism 119, mutant KRAS can increase dependence on aminotransferases through downregulation of GLUD, and drive increased production of NADPH to regenerate reduced glutathione and control ROS levels 34 (Figure 5).

Poor vascularization and hypoxia induce the stabilization of HIF1α or HIF2α 159, which directs glutamine towards biosynthetic fates that do not require oxygen. HIFα stabilization orchestrates a gene expression program that promotes the conversion of glucose to lactate, driving it away from the TCA cycle 159, 160. Decreased glucose entry into the TCA cycle can be compensated for by glutamine fueled production of the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate 151. However, this α-ketoglutarate is largely channeled through reductive carboxylation in certain cell types to produce citrate, acetyl-coA, and lipids 89–91. By contrast, glutamine is metabolized in human B-cell lymphoma model cells cultured in hypoxia largely via forward TCA cycling, with only a minor amount undergoing reductive carboxylation 151. HIFα stabilization can occur independently of hypoxia in tumors owing to mutations in factors involved in the degradation of HIFα subunits (such as von Hippel Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL)) 159 or through increased translation through mTOR 161, and glutamine itself can also increase HIFα stabilization 162–164. We suspect that as more genes and tissues are studied, glutamine metabolism will be found to be reprogrammed through modulation of the pathways described above (Table 1) and through novel direct mechanisms.

Glutamine Metabolism in the ClinicImaging

Reprogrammed cancer metabolism can be used to image tumors. Glucose-based 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) 165 has been in use for more than three decades to image and stage tumors via their avid uptake of glucose. However, some tissues, particularly the brain, also take up large amounts of glucose, making FDG-PET ineffective in imaging brain tumors 165. 18F-fluorinated glutamine (18F-(2S,4R)4-fluoroglutamine(18F-FGln)) was developed as a potential tumor imaging tracer and validated in animal models 166, 167, and 18F-FGln PET has since been evaluated clinically and shown promise in the diagnosis of glioma 168. Importantly, in glioma 18F-FGln accumulation does not necessarily suggest increased glutamine catabolism, as mouse orthotopic models of glioma and human patient samples show high rates of glutamine accumulation but comparatively low rates of glutamine metabolism 169–171. Nonetheless, 18F-FGln is a promising new tool in the diagnosis of cancers refractory to use of FDG such as glioma, and it will be of interest to determine if high 18F-FGln uptake in other tumor types is predictive of glutamine dependence and therapeutic response to inhibition of glutamine metabolism.

Therapy

The dependence of cancer cells on glutamine metabolism has made it an attractive anti-cancer therapeutic target. As detailed in Table 2, many classes of compounds that target glutamine metabolism, from initial transport in the cell to conversion to α-ketoglutarate, have been examined. While most of these are still in the preclinical ‘tool compound’ stage or have been limited by toxicity, allosteric inhibitors of GLS have shown promise in preclinical models of cancer, and one highly potent compound in this class, CB-839, has moved on to clinical trials. A preclinical tool-compound inhibitor of GLS is bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) 172, which has been shown to block the growth of cancer cells in vitro, of xenografts in vivo, and to slow tumor growth and prolong survival in genetically engineered mouse models of cancer 151, 173. CB-839 has shown efficacy against triple negative breast cancer and hematological malignancies in preclinical studies 53, 54, and is currently the subject of several clinical trials.

Table 2.

Strategies to pharmacologically target glutamine metabolism in cancer

ClassDrugStatus

| Glutamine mimic | ||

| Glutamine depletion | ||

| GLS inhibitors | ||

| SLC1A5 inhibitors | ||

| GLUD inhibitors | ||

| Aminotransferase inhibitors | ||

| SLC7A11 or xCT system inhibitors |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AOA, aminooxyacetate; DON, 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; γ-FBP, γ-folate binding protein; GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; GPNA, L-γ-glutamyl-p-nitroanilide.

The transition of glutaminase inhibition to the clinic will be aided by understanding potential inherent or acquired resistance mechanisms. Cancers that depend on GLS2 61, 64, which is not sensitive to BPTES or CB-839, would be unlikely to respond to therapy 174. The expression of pyruvate carboxylase, which can provide carbon to the TCA cycle through its conversion of pyruvate to oxaloacetate, represents a potential mechanism for glutaminase independence120, 175. Glutamine synthetase (GLUL) expression may also predict glutamine independence and promote BPTES resistance 171, 176–178.

Metabolic synthetic lethality and combination therapy

The heterogeneity, varied oncogenotypes, and microenvironment of tumors pose considerable challenges to targeted therapies, but the use of combination therapy is a successful paradigm in the treatment of HIV and certain types of cancers. Particularly attractive drug combinations induce synthetic lethality, where two drugs induce cell death in combination but not individually. Many candidate preclinical synthetic lethal treatments target pathways or cellular functions that help cancer cells to compensate for the targeting of another pathway or cellular function. The pleiotropic role of glutamine in cellular functions, such as energy production, macromolecular synthesis, mTOR activation, and ROS homeostasis 179, makes GLS inhibition a potentially ideal candidate for combination therapy, as detailed in Table 3. A few combinations are notable because they reveal novel consequences of glutamine metabolism. Specific inhibition of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 synergizes with glutaminase inhibition 53, consistent with the described role of glutamine in controlling expression and activity of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, as reviewed recently 180. Similarly, the synergism between glutamine withdrawal and chemical activation of the ISR with the retinoid-derivative fenretinide 65 shows that glutamine can suppress this stress response through various mechanisms, as discussed above. While invasive and metastatic cells have not specifically been studied for their sensitivity to glutaminolysis inhibition, it has been shown that highly invasive ovarian cancer cells have increased glutamine dependence compared to less invasive cells 181, and metastatic prostate tumors show increased glutamate availability and dependence on glutamine uptake 93, 182. Indeed, genetic inhibition of glutaminase was shown to prevent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a key step in tumor cell invasiveness and eventual metastasis 183. Thus, prevention of metastasis may be another avenue to focus on the development of combinatorial strategies in glutamine metabolic inhibition.

Table 3.

Treatments that are synthetically lethal with inhibition of glutamine metabolism

Co-treatmentRationale

| Metformin | Metformin decreases glucose oxidation to increase cellular dependence on glutamine 247. |

| GLUT1 inhibition | Combined downregulation of glucose transport (Apigenin) and glutaminase causes severe metabolic stress 248. |

| Glycolysis inhibition (2-DG) | Blocking of compensatory glutamine contribution to TCA cycle, nucleotides and mTOR signaling blocks growth in 2-DG resistant cells 249. |

| Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibition | Specific chemical inhibition of pyruvate transport into the mitochondrion synergizes with inhibition of glutaminolysis to cause increased death 250. |

| Transglutaminase inhibition | Combined inhibition of glutaminase and transglutaminase causes potentially lethal acidification 251. |

| mTOR inhibition | Consistent with the role of glutamine in mTOR activation 219 and mTOR control of metabolism, GLS and mTOR inhibition are synthetic lethal 252. |

| ATF4 activation | Glutamine withdrawal activates the ISR, and further activating this pathway with the retinoid-derivative fenretinide causes increased cancer cell death 65. |

| BCL-2 inhibition | Inhibiting GLS causes apoptosis through altered metabolism, with the effect exacerbated by inhibition of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 53. |

| HSP90 inhibition | Consistent with a role of GLS in controlling ROS and ER stress, HSP90 and GLS inhibition cause ER stress-induced cell death via ROS 253. |

| BRAF inhibition | BRAF inhibition resistance causes a shift to glutamine dependence, and so combination therapy may be used to combat this resistance 254. |

| NOTCH inhibition | NOTCH1 promotes glutaminolysis in T-ALL, sensitizing NOTCH inhibited T-ALL cells to genetic and pharmacological GLS inhibition 255. |

| EGFR inhibition | GLS inhibition restores sensitivity to the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib in cells which had developed resistance 256. |

ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; 2-DG, 2-deoxyglucose; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GLS, kidney-type glutaminase; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; ISR, integrated stress response; ROS, reactive oxygen species; T-ALL, T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

The effects of metabolic inhibitors in vivo may also broadly influence immunity. There has been a recent surge of interest in manipulating the immune response to target cancer, either through the blocking of immune checkpoints or the use of engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. These approaches require immune cells to function within the tumor microenvironment. Recent work has indicated that immune cells compete with cancer cells for glucose 184, and we speculate that perhaps this may be true for glutamine as well. In fact, glutamine metabolism is increased in T-cell activation and regulates skewing of CD4+ T-cells towards more inflammatory subtypes 32, 185, 186. While ex vivo experiments suggest that lymphocytes show signs of proper activation even in the presence of CB-839 173, it remains to be seen how GLS inhibition will affect anti-tumor immunity in vivo. Studies in mouse lymphocytes suggest that the CB-839-insensitive GLS2 may play a key role in lymphocyte proliferation 144, and so targeting of glutamine metabolism through the modulation of tumor-specific pathways may be required to maintain both high glutamine availability and immune response.

Glutamine Usage: Plastic versus Patient

While the critical role of glutamine metabolism in cancer cells in vitro is well established, less clear is what role glutamine plays in tumors in vivo, which can face shortages of nutrients and oxygen 7. Not surprisingly, tumors utilize a variety of nutrients as carbon sources and energy besides glucose and glutamine, including lipids and acetate 187–189, and may also utilize macropinocytosis to support amino acid pools 22. However, the circumstances under which macropinocytosis becomes dominant in vivo remain to be established. As an illustrative example of the metabolic complexity of tumors, lung cancer cell lines are often glutamine dependent in vitro, but a recent study of K-RAS driven mouse lung tumors demonstrated that glucose but not glutamine was preferentially used to supply carbon to the TCA cycle, through the action of pyruvate carboxylase 190. Furthermore, two recent metabolomics and metabolic flux studies of primary human lung cancer showed little change in glutamine entry into the TCA cycle, and instead suggested that human lung cancer can synthesize glutamine from the TCA cycle 120, 191. Human and mouse gliomas exhibit high rates of glucose catabolism and accumulate but do not avidly metabolize glutamine 168, and do not depend on circulating glutamine to maintain cancer growth, but instead utilize glucose to synthesize glutamine through glutamine synthetase to support nucleotide biosynthesis 169–171. Hence, much more work is needed to further define the use of nutrients in vivo, to guide the selection of metabolic therapies in the clinic.

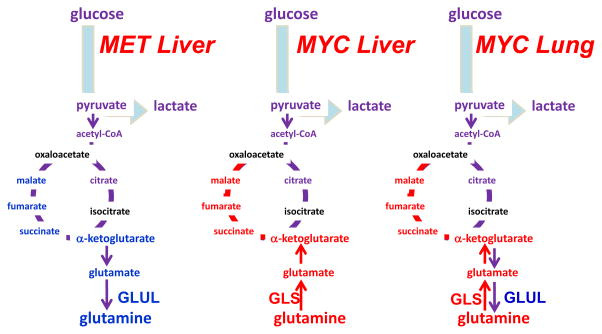

Nevertheless, glutamine metabolism has been documented as critical for tumorigenesis and tumor survival in specific in vivo models 151, 173, 192, 193, which have varied metabolic profiles depending on the tumor oncogenotype. The complexities in vivo are exemplified by a study utilizing mouse models to compare the effects of metabolic driver and tissue of origin on tumor metabolism 177 (Figure 8). MET-driven liver tumors expressed glutamine synthetase and so presumably made their own glutamine from glucose flux, and thus do not need to take up glutamine from the environment. Likewise, MYC-driven lung tumors upregulated both GLS and glutamine synthetase, consistent with a recent study showing that MYC indirectly induces glutamine synthetase 177, 178. Conversely, MYC-driven liver tumors upregulated GLS and SLC1A5 and avidly consumed and catabolized glutamine 173, 177 (Figure 8). In fact, in this same MYC-driven liver cancer model, loss of a single copy of GLS slowed tumor growth and pharmacologic inhibition of GLS prolonged survival 173, suggesting the critical importance of glutamine metabolism in certain cancer settings. The heterogeneity of glutamine metabolism in tumors arising in the same tissue type, demonstrated by the MYC and MET driven liver models, is mirrored in studies of human breast cancer that show that ER+ breast cancer cell lines are less glutamine dependent than triple negative breast cancer cell lines 18, 54, 176. This finding is further supported by a study in primary ER− human breast tumors that shows high glutamine to glutamate ratio in the tumors, suggesting increased glutamine catabolism 194.

Figure 8. Differing requirements for glutamine in cancer based on oncogene and tissue of origin.

The oncoproteins MET and MYC lead to differing dependence on glutamine in different cancer types, which is partially influenced by differential expression of glutamine synthetase (GLUL) or glutaminase (GLS). α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; OAA, oxaloacetate; Illustration is drawn from primary data originally presented in Yuneva et al.177.

Altered glutamine metabolism can interact with the tumor microenvironment in surprising ways. Increased lactate, which may be present in the microenvironment as a consequence of increased glycolysis by cancer cells 7, has been shown to promote increased glutamine metabolism via a HIF2 and MYC-dependent mechanism 195, potentially providing a way for an evolving tumor to ‘reprogram’ itself towards increased glutaminolysis. Similarly, as discussed above, increased glutaminolysis causes an increase in excreted ammonia and autophagy in exposed cells 137, 138, and indeed, a study with co-culture of breast cancer cells and fibroblasts showed that the ammonia released from breast cancer cells stimulated autophagy in the fibroblasts to release additional glutamine, which was then taken up and metabolized by the cancer cells 196. However, ammonia can be toxic to surrounding cells, and since tumors engaging in glutaminolysis may excrete large amounts of ammonia, it is still unknown how surrounding non-transformed cells detoxify this ammonia. Finally, some tumors, particularly those of the brain and the lung 120, 169–171, 191, may synthesize and excrete glutamine, and it is still not known how this increased glutamine in the microenvironment may affect the physiology of neighboring cells. Understanding the interaction between tumor microenvironment, tissue-of-origin and oncogenic drivers may be the key to deconvoluting the potential role of glutamine in different tumor types.

Concluding remarks

Ninety years ago, Warburg uncovered that many animal and human tumors displayed high avidity for glucose, which was largely converted to lactate through aerobic glycolysis. Warburg also suggested that cancers are caused by altered metabolism and loss of mitochondrial function. These dogmatic views have been replaced and refined over the last several decades with the emergence of oncogenic alterations of metabolism, appreciation of the importance of mitochondrial oxidation in cancer physiology, and the rediscovery of the role of glutamine in tumor cell growth in addition to the pivotal role of glucose. Here, we provide an updated overview of glutamine metabolism in cancers and discuss the complexity of metabolic re-wiring as a function of the tumor oncogenotype as well as the microenvironment that adds to the heterogeneity found in vivo. In certain types of cancers, such as those driven by MYC, tumor cells appear to depend on glutamine, and hence targeting glutamine metabolism pharmacologically may prove to be beneficial. Conversely, different oncogenic drivers may result in tumor cells that could bypass the need for glutamine. Targeted inhibition of some oncogenic drivers, however, has been reported to re-wire cells to become dependent on glutamine, and hence targeted inhibitors could be synthetically lethal with inhibition of glutamine metabolism. Overall, the field of cancer metabolism has made considerable progress in understanding alternative fuel sources for cancers including glutamine, which under specific circumstances can be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

Key points.

결론

90년 전, 워버그는 많은 동물과 인간의 종양에서

포도당에 대한 높은 친화성을 발견했으며,

이는 주로 유산소 당분해 과정을 통해 젖산으로 전환되었다.

워버그는

또한 암이 대사 이상과 미토콘드리아 기능 상실로 인해 발생한다고 제안했습니다.

이러한 전통적인 관점은

지난 수십 년간 암 유발성 대사 변화의 발견,

암 생리학에서 미토콘드리아 산화의 중요성 인식,

포도당 외에도 글루타민의 종양 세포 성장에 대한 역할 재발견과 함께 대체되고 정교화되었습니다.

본 연구에서는

암에서의 글루타민 대사 최신 동향을 종합적으로 검토하며,

종양의 발암 유전자형 및 미세환경에 따라 발생하는 대사 재편의 복잡성을 논의합니다.

MYC에 의해驱动되는 특정 유형의 암에서는

종양 세포가 글루타민에 의존하는 것으로 나타났으며,

따라서 약리학적 방법으로 글루타민 대사를 표적화하는 것이 유익할 수 있습니다.

반면,

다른 종양 유발 인자는

종양 세포가 글루타민에 대한 의존성을 우회할 수 있도록 할 수 있습니다.

그러나

일부 종양 유발 인자의 표적 억제는 세포를 글루타민에 의존하도록 재편할 수 있으며,

따라서 글루타민 대사 억제제는 글루타민 대사 억제와 합성 치사 효과를 가질 수 있습니다.

전반적으로 암 대사 분야는

글루타민을 포함한 암의 대체 연료 원천에 대한 이해에서 상당한 진전을 이루었으며,

특정 조건 하에서 치료 목적으로 활용될 수 있습니다.

핵심 포인트.

- 암 세포는 글루타민의 소비와 의존도가 증가합니다.

- 글루타민 대사는 암 세포에서 트리카르복실산(TCA) 회로, 뉴클레오티드 및 지방산 생합성, 산화환원 균형을 지원합니다.

- 글루타민은 mTOR 신호전달을 활성화하고 내소체 스트레스를 억제하며 단백질 합성을 촉진합니다.

- 암 세포는 글루타메이트를 두 가지 다른 경로(글루타메이트 탈수소효소 또는 아미노전달효소)를 통해 알파-케토글루타르산으로 대사할 수 있으며, 아미노전달효소는 더 생합성적이고 성장 촉진적인 표현형을 지원할 수 있습니다.

- 종양 유발 경로의 활성화와 종양 억제 인자의 상실은 조직 특이적으로 글루타민 대사를 재프로그래밍합니다.

- 글루타민 대사 표적화는 항암 치료법으로 유망합니다. 암 치료로 인한 보상성 글루타민 대사는 글루타민 대사 표적화가 병용 치료에 활용될 수 있음을 시사합니다.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralph DeBerardinis (Children’s Research Institute at UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX) and Jonathan Coloff (Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for helpful commentary and discussion. We apologize to any authors whose work could not be included due to space limitations. This work is partially supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01CA057341 (C.V.D), The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society LLS 6106-14 (C.V.D.), and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute. B.J.A and Z.E.S were supported by the NCI F32CA180370 and F32CA174148, respectively.

Glossary2-Hydroxyglutarate

An α-hydroxy acid sometimes produced at high levels by cancer cells, which structurally resembles α-ketoglutarate and so inhibits α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes such as the jumonji-family histone demethylases. The D-2HG enantiomer is produced downstream of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase enzymes in glioma and acute myelogenous leukemia, and the L-2HG enantiomer is produced under hypoxia.

Aminotransferases

A class of enzymes, also known as transaminases, which catalyze the reaction between an α-keto acid such as pyruvate and an α-amino acid to form a different amino acid and α-keto acid. For example, glutamic-pyruvate transaminase (GPT, alanine aminotransferase) transfers a nitrogen from glutamate to pyruvate to make alanine and α-ketoglutarate.

Autophagy

Refers to the macroautophagy, which is a process of bulk cytoplasmic and organelle degradation by specialized organelles called autophagosomes, which then deliver the contents to the lysosome. Autophagy is increased under many forms of stress and can provide nutrients for metabolism.

Cap-dependent translation

In most eukaroyotic mRNAs, translation relies on the initiation factor eIF4E binding to the 5′ mRNA cap (a modified nucleotide), along with the ribosome and other initiation factors. Certain stress pathways including ER stress and the ISR inhibit cap-dependent translation through inhibitory phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α.

Caloric restriction

Restricting the available calories to a model organism, such as a mouse or C. elegans, without under-nourishing them. Caloric restriction has been shown in several species to delay age-associated diseases and dramatically extend lifespan.

Electron transport chain

A series of transmembrane protein complexes, present on the inner membrane mitochondria, which transfer electrons via redox reactions to the terminal electron acceptor oxygen, which is reduced with binding of protons to a water molecule. This generates a proton gradient that powers ATP synthase to produce ATP. Premature leakage of electrons to oxygen can lead to production of ROS.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

Refers to various stresses that lead to protein misfolding and activate the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR, which shares molecular machinery with the ISR, halts cap-dependent translation, induces expression of ER chaperone proteins, and can lead to death if the stress is not resolved.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

A complex process observed in invasive solid tumors of epithelial origin in which the cancer cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype, break through the basement membrane, and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system via the process of intravasation. EMT is promoted by many genetic, epigenetic, and physiologic alterations commonly found in cancer.

Ferroptosis

An intracellular iron-dependent form of cell death that is distinct from apoptosis.

Glutathione

A tripeptide (glutamate-cysteine-glycine) which acts as an important antioxidant. The reduced form (GSH) can react with H2O2 to form the oxidized form (GSSG).

Hexosamine

A nitrogenous sugar created from a monosaccharide and amino acids that can be used to modify proteins to aid in protein folding and trafficking.

Integrated stress response (ISR)

A stress response pathway that responds to various cellular insults, including amino acid deprivation, through the GCN2 kinase, to phosphorylate eIF2α halt general cap-dependent protein translation, and increase transcription of endoplasmic reticulum chaperone proteins. The ISR may eventually result in apoptotic cell death if the stress is not resolved.

Macropinocytosis

A type of endocytosis where extracellular fluid and nutrients are engulfed and taken up into vesicles called macropinosomes. The contents can then be digested by lysosomal degradation to provide nutrients for metabolism.

Oncogenotype

The genetic or epigenetic alterations (to activate an oncoprotein or disable a tumor suppressor pathway) that drive the evolution and phenotype of a given tumor.

One-carbon metabolism pathway

A pathway centered on the metabolism of folate, an important carbon donor for DNA methylation and purine nucleotide synthesis. This pathway is linked to the de novo biosynthesis pathways of serine and glycine.

Reductive carboxylation

A process that occurs in some normal and cancer cells whereby α-ketoglutarate proceeds ‘backwards’ through the TCA cycle, being reduced through the consumption of NADPH by isocitrate dehydrogenase in the non-canonical reverse reaction to form citrate. This citrate may then be used in fatty acid synthesis.

Serine and glycine biosynthesis