자가면역질환의 치료는 어렵지 않다.

자가면역으로 인한 염증을 악화시키는 밀가루(글루텐), 포도당(인슐린유사성장인자), 우유(락타아제가 없는 사람)를 끊고

자가면역 항원으로 작용하는 음식요인을 제거하고

항염증 효과가 있는 DHA, 오메가 3지방산을 에너지원으로 하는 케톤에너지 대사체제로 바꾸고

항염증 효과가 있는 비타민, 미네랄을 잘 섭취

그리고

마음치유를 위한 기도, 명상 등을 병행한다

질병의 natural history를 알기위해서는 정확한 진단이 선행되어야 한다.

서 론

전신성 홍반성 루푸스(systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE)는 특정 핵항원에 대한 자가항체 생성을 특징으로 하는 자가면역 질환이다. 이런 자가항체들은 면역복합체를 형성시키고 조직에 침착되어 염증과 조직손상을 유발시키게 된다. 임상양상은 매우 다양하며, 젊은 가임기 여성에서 가장 많지만 성별과 나이, 인종의 구분없이 발생할 수 있다. 원인은 정확히 알려져 있지 않으나 감수성 유전자와 환경적 요인들의 상호작용에 의해서 비정상적인 면역반응이 유발됨으로써 발생한다. 이러한 면역반응에는 T 및 B 림프구의 과도한 반응성과 부적절한 조절로 인해서 비정상적인 면역반응을 보인다. 루푸스의 치료는 지난 한 세기 동안 생존률과 삶의 질에서 비약적인 발전을 가져왔다. 이런 발전은 비약물적 치료와 약물치료가 포함된다. 루푸스 치료의 전환점은 1950년대에 코르티코스테로이드의 발견과 사용이며, 1960년대와 1970년대에 신투석과 싸이클로포스파마이드에 있다. 비약적 발전의 핵심은 루푸스가 여러 증상과 징후가 모인 스펙트럼과 같은 질환(a spectrum of disease)이라는 것이며, 따라서 각기 환자 의 개별적인 소견에 근거해서 치료해야 한다.

하나의 치료 방법이 한 사람에게는 맞지만 다른 사람에게는 맞지 않을 수 있기 때문에 치료는 개인화(individualized) 되어야 한다. 루푸스의 성공적인 치료는 증상과 내재적인 염증의 치료에 기반하며 주요 장기침범 및 비가역적인 진행을 막거나 낮추는데 목료로 한다. 최근에 바이오테크놀로지의 빠른 발전은 루푸스의 더욱 새롭고 특이적인 치료에 기여할 것으로 보인다.

진단

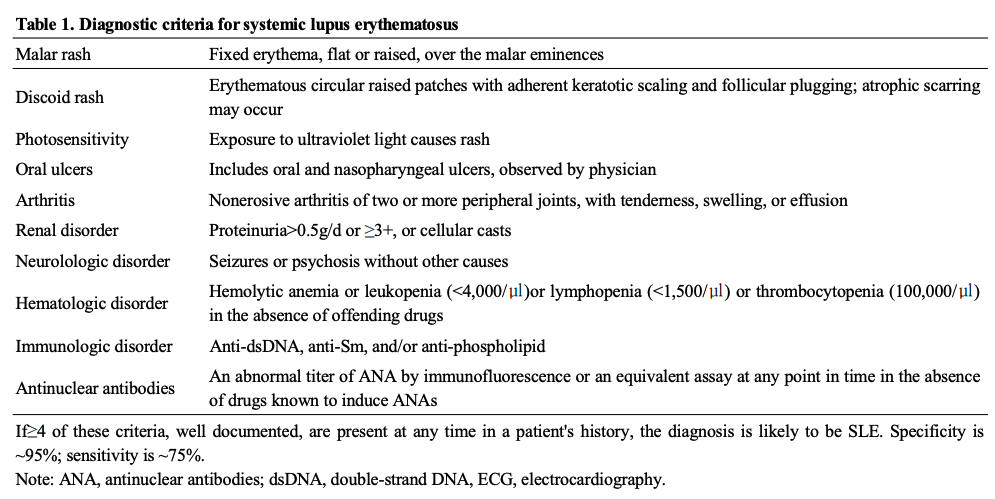

루푸스의 진단은 특징적인 임상소견에 근거하며 자가항 체를 포함하는 검사실소견이 도움이 된다. 임상증상은 매우 경미하고 간헐적인 양상으로부터 지속적이고 전격적인 양상까지 다양하다. 대부분은 임상적 악화가 반복되며 그 사이의 안정기를 갖게 된다. 대개 발열, 피로, 권태감, 식욕감퇴, 체중 감소 등의 전신증상을 동반한다. 현재 사용되는 진단 기준은 미국 류마티스학회에서 제안하는 루푸스의 분류기준에 따른다 (표 1)

진단기준은 11개의 기준항목 중에서 4개 이상의 항목 이 확인되면, 환자가 루푸스를 가지고 있을 가능성이 높다 (특이도와 민감도는 각각 90%와 75%). 많은 환자들에서 시 간이 경과함에 따라 추가적으로 진단기준에 부합된다. 자가 항체는 발병초기부터 발견될 수 있다. 항핵항체(antinuclear antibody, ANA)는 선별검사로 가장 적합하다. 항핵항체는 질병 경과 중에서 95% 이상의 환자들에게서 양성이므로, 반복적으로 음성이 나오면 루푸스가 아닐 가능성을 시사한다. 항핵 항체는 일부 정상인에서도 낮은 역가로 나타날수 있으며 나이가 들수록 그 출현빈도는 증가한다. 이중나선(double stranded) DNA에 대한 고역가의 IgG 항체와 Sm 항원에 대한 항체는 모두 루푸스에 특이적이다. 따라서 합당한 임상증상이 있을 경우, 진단에 도움이 된다. 루푸스에 부합되는 임상증상없이 다양한 자가항체만 양성인 경우 루푸스로 진단해서는 안된 다. 4개 이상의 진단항목을 충족시키지 못하지만 루푸스가 의심될 경우 lupus-like syndrome이라고 부르기도 한다.

1. 비약물적 치료

일반적인 치료는 루푸스 악화(flare)의 발생과 진행을 제한시킬 수 있다. 많은 환자에서 가장 중요한 치료는 햇빛을 피하는 것이다. 특히 피부침범을 보이는 경우라면 더욱 강조 된다. 자외선에 노출될 경우 sun protection factor (SPF) 25 이상의 자외선 차단크림을 사용하고 햇빛보호용 옷을 착용하는 것이 권장된다. 많은 자외선 노출은 광과민성 발진(photosensitive rash)뿐만 아니라 증상의 악화를 일으킨다. 또한 창문을 통한 자외선과 형광 등은 질환활성화를 일으킬 수 있으므로, 창문에 보호용 필름과 형광등에 차단막을 부착하여 위험을 줄이 도록 한다. 외국여행에 대비한 백신접종은 금기는 아니지만 하루 10 mg 이상의 프레드니솔론을 복용하거나 면역억제제를 복용하는 사람에게서 생백신의 사용은 피해야 한다. 백신에 대한 면역반응은 질적 및 양적으로 건강한 사람과는 다르다. 에스트로겐 피임약을 많이 복용하는 것은 피하여야 하고, 소량의 에스트로겐이나 프로게스테론만 있는 피임약 혹는 다른 피임방법이 요구된다. 호르몬 대체요법은 일부 루푸스 환자에서 투약시작 직후 악화를 일으킬 수 있으므로 논란이 되고 있다. 그 밖의 일반적인 방법은 스트레스를 피하고 적절하게 휴식을 취하고 포화지방이 적은 어유(fish oil)를 많이 먹는 것이다. 루푸스 환자에서 항진된 동맥경화증으로 인한 조기 사망이 자주 발생된다. 따라서 금연과 같은 심장을 보호하는 생활방식이 필요하다.

Vitamin D status in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): A systematic review and meta-analysis

Author links open overlay panelMd. AsifulIslamaShahad SaifKhandkerb1Sayeda SadiaAlamb1PrzemysławKotylacRoslineHassana

Show more

Add to Mendeley

Share

Cite

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102392Get rights and content

Highlights

•

Significantly low levels of serum vitamin D are observed in SLE patients compared to healthy subjects.

•

Latitude, season and medications could be the risk factors in inadequate vitamin D in SLE.

•

Vitamin D supplementation with regular monitoring should be considered as part of SLE management plans.

•

Vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in SLE is a cause or consequence, or both is still a matter of debate.

Abstract

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease where chronic inflammation and tissue or organ damage is observed. Due to various suspected causes, inadequate levels of vitamin D (a steroid hormone with immunomodulatory effects) has been reported in patients with SLE, however, contradictory.

Aims

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the serum levels of vitamin D in patients with SLE in compared to healthy controls.

Methods

PubMed, SCOPUS, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar electronic databases were searched systematically without restricting the languages and year (up to March 2, 2019) and studies were selected based on the inclusion criteria. Mean difference (MD) along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used and the analyses were carried out by using a random-effects model. Different subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted. Study quality was assessed by the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and publication bias was evaluated by a contour-enhanced funnel plot, Begg's and Egger's tests.

Results

We included 34 case-control studies (2265 SLE patients and 1846 healthy controls) based on the inclusion criteria. Serum levels of vitamin D was detected significantly lower in the SLE patients than that in the healthy controls (MD: −10.44, 95% CI: −13.85 to −7.03; p < .00001). SLE patients from Asia (MD: −13.75, 95% CI: −21.45 to −6.05; p = .0005), South America (MD: -3.16, 95% CI: −4.62 to −1.70; p < .0001) and Africa (MD: −16.15, 95% CI: −23.73 to −8.56; p < .0001); patients residing below 37° latitude (MD: −11.75, 95% CI: −15.79 to −7.70; p < .00001); serum vitamin D during summer season (MD: -7.89, 95% CI: −11.70 to −4.09; p < .0001), patients without vitamin D supplementation (MD: -15.57, 95% CI: −19.99 to −11.14; p < .00001) or on medications like hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids or immunosuppressants without vitamin D supplementation (MD: -16.46, 95% CI: −23.86 to −9.05; p < .0001) are in higher risk in presenting inadequate serum levels of vitamin D. The results remained statistically significant from different sensitivity analyses which represented the robustness of this meta-analysis. According to the NOS, 91.2% of the studies were considered as of high methodological quality (low risk of bias). No significant publication bias was detected from contour-enhanced and trim and fill funnel plots or Begg's test.

Conclusion

Inadequate levels of serum vitamin D is significantly high in patients with SLE compared to healthy subjects, therefore, vitamin D supplementation with regular monitoring should be considered as part of their health management plan

Significance and impact of dietary factors on systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis (Review)

- Authors:

- Maria‑Magdalena Constantin

- Iuliana Elena Nita

- Rodica Olteanu

- Traian Constantin

- Stefana Bucur

- Clara Matei

- Anca Raducan

- Published online on: November 16, 2018 https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6986

- Pages: 1085-1090

Metrics: Total Views: 34186 (Spandidos Publications: 8880 | PMC Statistics: 25306 )

Total PDF Downloads: 4940 (Spandidos Publications: 3154 | PMC Statistics: 1786 )

Cited By (CrossRef): 10 citations View Articles

Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, although its mechanisms involve genetic, epigenetic and environmental risk factors. Considering that SLE pathogenesis is yet to be explored, recent studies aimed to investigate the impact of diet, in terms of triggering or altering the course of the disease. To study the impact of diet on SLE pathogenesis, we conducted a search on Pubmed using the keywords ‘diet and autoimmune diseases’, ‘diet and lupus’, ‘caloric restriction and lupus’, ‘polyunsaturated fatty acids and lupus’, ‘vitamin D and lupus’, ‘vitamin C and lupus’ ‘vitamin E and lupus’ ‘vitamin A and lupus’ ‘vitamin B and lupus’, ‘polyphenols and lupus’, ‘isoflavones and lupus’, ‘minerals and lupus’, ‘aminoacids and lupus’, ‘curcumin and lupus’ and found 10,215 papers, from which we selected 47 relevant articles. The paper clearly emphasizes the beneficial role of personalized diet in patients with SLE, and the information presented could be used in daily practice. Proper diet in SLE can help preserve the body's homeostasis, increase the period of remission, prevent adverse effects of medication and improve the patient's physical and mental well‑being.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototype of autoimmune disease, of unknown etiology, although its mechanisms involve genetic, epigenetic and environmental risk factors. Considering that SLE pathogenesis is yet to be explored, recent studies aimed to investigate the impact of diet on the disease, in terms of triggering or altering the course of SLE (1,2).

There are trillions of germs inside the human gut, the microbiota, on which scientists' attention has been focused on, due to its potential to elicit the development of autoimmune disease in genetically predisposed individuals, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes (2,3). However, the pathogenic role of the microbiota in SLE is yet to be revealed (4,5).

Search methods

To study the impact of diet on SLE pathogenesis, we conducted a search on Pubmed on October 2017 using keywords ‘diet and autoimmune diseases’, ‘diet and lupus’, ‘caloric restriction and lupus’, ‘polyunsaturated fatty acids and lupus’, ‘vitamin D and lupus’, ‘vitamin C and lupus’, ‘vitamin E and lupus’, ‘vitamin A and lupus’, ‘vitamin B and lupus’, ‘polyphenols and lupus’, ‘isoflavones and lupus’, ‘minerals and lupus’, ‘aminoacids and lupus’ respectively ‘curcumin and lupus’ and identified 7,071, 403, 13, 441, 519, 46, 53, 62, 216, 6, 4, 143, 1,227, respectively, 11 articles matching search criteria. From a total of 10,215 papers, we reviewed the most relevant and updated articles and eliminated the papers we considered to be irrelevant for the design of our study, based on the title and abstract. We took into account publisher's prestige, credibility and prestige of the journal and validity and importance of data presented. In total, 9,521 records were excluded after reading the title and year of publication, 474 records were excluded after abstract reading, 92 full-text articles were excluded, 128 records were screened and 55 records were included. All publications included were in English.

Given that this review was limited to studies published in the English language and indexed in only one database, PubMed, we may have missed some important articles.

Dietary factors

Research on dietary influences on SLE has focused on vitamin D, vitamin A and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Dietary changes in SLE, meaning diet supplementation with vitamins A, D, E, polyunsaturated fatty acids and phytoestrogens showed a decrease in proteinuria and glomerulonephritis in animal models (5).

There is now clear evidence that environmental factors have a high influence on SLE development, since there is a lower prevalence of the disease in West Africans than in African Americans, though both groups have the same ethnicity. The proposed theories to support this difference include the use of antibiotics and the hygiene hypothesis, which lead to the removal of some species of microbes that may have a protective role against SLE (2).

The outstanding role that food plays is sustained not only by its nutritional value, but also by its capacity to modify the structure and function of the gut microbiota.

An adequate diet is also important to help fight the associated comorbidities in SLE which increase the cardiovascular risk: diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia and obesity (6).

The lipid profile alterations due to medication (chronic corticotherapy) or as a result of disease activity, are aggravated by hyperlipid diet (7). Higher levels of total cholesterol and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), an increase in triglycerides (TG) and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) have been noted (8).

Caloric restriction

At the moment, information regarding the impact of diet on autoimmune diseases is yet insufficient. However, caloric restriction was proven to induce various benefits to the immune system, since this restriction also leads to changes in the gut microbiota (5).

Obesity among SLE adults is a real concern, since up to 40–50% of these patients are obese and more prone to suffer from fatigability (9–11). For this group of SLE patients, losing weight by keeping a low glycemic index or a low-calorie diet also proved to be efficient in lowering the level of fatigue, though the disease activity was not influenced by diet (12).

Reducing the caloric intake has helped to prevent the disease progression and the antiphospholipid syndrome in mice. In humans, one study monitoring the dietary impact of two isocaloric diets on SLE emphasized that the diet with higher level of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) reduce the risk of fetal loss and symptoms in women with SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome (13).

Strong evidence supports the idea that hypocaloric diet is positively related to disease activity. Therefore, the adequate caloric ratio for women is around 1,000–1,200 kcal/day and for men 1,200–1,400 kcal/day, with special regards to obese patients or with a tendency towards obesity, as well as SLE patients undergoing long-term or high-dose corticotherapy (14).

Other lifestyle habits that may help alleviate symptoms in SLE enclose smoking cessation and physical exercise, preferably aerobic, since it is safer (15). It may also be useful for patients with SLE to benefit from individualized nutrition counseling, which was shown to be effective in initiating dietary changes (16).

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

In patients with stable disease a diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids may have a positive impact on overall clinical status (15). Omega-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentanoic acid and docosahexanoic acid, elicit an anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing the level of C reactive protein (CRP) and other inflammatory mediators (17,18). Caloric restriction and well-established diet supplementation with omega-3 PUFA, eicosapentanoic acid and docosahexanoic acid (at a ratio of 3:1), regulates levels of total cholesterol, LDL-C and TG. Apart from the anti-inflammatory effect, adding omega-3 PUFA in SLE patients diet protects against free radicals and helps defend cardiovascular alteration by reducing the level of antibodies (anti-dsDNA), interleukins (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2) and TNF-α, and regulating proteinuria and blood pressure (6,18). Other omega-3 acids like α-linolenic acid and Υ-linolenic acid also have beneficial effects by limiting TNF-α and IL-2 secretion. No downsides of introducing omega-3 PUFA to SLE patients' diet were found, as opposed to omega-6 PUFA supplementation, which may exacerbate SLE activity (6).

The main sources for omega-3 PUFA are krill oil, fish oil, olive oil, canola oil, flaxseed oil, fish (salmon, tuna, sardine, herring), but it may be found in primrose oil and soybean oil (6,19). Krill oil extracted from the Antarctic krill is considered superior to fish oil since it contains a higher amount of omega-3 PUFA and it has an antioxidant effect, reducing the inflammatory joints infiltrate (19).

With a concentration of 70% omega-3 PUFA and rich in α-linolenic acid, flaxseed oil daily intake of 30 g can lower serum creatinine in SLE patients with renal dysfunction (6,20). High dosage of fish oil (18g/day) is also beneficial in reducing TG level to up to ~40%, while increasing HDL-C by a third (21,22).

Omega-3 PUFAs inhibit leukocyte chemotaxis, adhesion molecule expression and production of inflammatory cytokines, through the action of specialized pro-resolving mediators, such as lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, and maresins, which reduce inflammation (23). Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, omega-3 fatty acids found in oily fish, are able to partly inhibit inflammation, but further clinical trials are required to see their effects on SLE. Dose-dependent actions of marine n-3 PUFA on inflammatory responses have not been well described, but it appears that at least 2 g/day is necessary to achieve an anti-inflammatory effect (24).

Proteins

Moderate protein intake of 0,6 g/kg/day is useful for improving renal function in SLE patients (25) and mouse studies led to the conclusion that a limitation in consumption of phenylalanine and tyrosine could also be of some benefit (25,26). The major sources of proteins are meat and eggs.

Fibers

The daily intake of fibers found in whole cereals, fruits and vegetables, should be around 38 g for men and 25 g for women, in order to reduce post-prandial glycemia and lipids level, regulate hyperlipidemia, and lower blood pressure and C reactive protein. As far as fiber consumption is concerned, adequate water intake should be considered, and exceeding fiber intake has to be avoided because it can lead to low absorption of nutrients (6).

Vitamins

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone with essential role on mineral metabolism and immune system homeostasis, and its deficiency has been associated with a higher susceptibility of SLE and more severe disease activity, especially in patients with dark skin (2,3).

Medical data show that the active form of vitamin D (calcitriol) may boost the innate immune response, regulating the T and B cell responses. Therefore, a lower level of vitamin D can be a risk factor for triggering not only SLE, but also other autoimmune diseases (27,28).

Sunlight exposure is known to stimulate vitamin D production, but this elicits a controversy since SLE patients have photosensitivity. Patients with SLE are advised to use sunscreens daily even if they do not see the sun, ~80% of UV penetrates the clouds and the fog (29). In this case, dietary supplementation of vitamin D may be beneficial (30). In fact, some studies postulate that high doses of vitamin D (up to 50,000 IU/day) have a preventive role, but similar improvements were obtained with doses of 2,000 IU/day (2,31).

According to Antico et al (28) several studies revealed that the level of vitamin D in SLE patients was <30 ng/ml in 56–75% of cases, whereas the same low level was found at a lower rate in healthy individuals (36–55%). This may be due to the fact that SLE patients avoid sun exposure. Ritterhouse et al (27) stated that healthy individuals with positive ANA have a higher predisposition to vitamin D deficiency than ANA negative persons.

Low levels of vitamin D are associated to high score of SLE activity-SLEDAI (32). Vitamin D supplementation brings significant beneficial effects on bone mineral density if it can reach a plasma level of >36,8 ng/l (30) but also on dendritic cells maturation and activation (33).

Several studies conducted on vitamin D supplementation (2 µg/day of cholecalciferol and/or alfacalcidol) have not proven any improvement in the clinical outcome of patients, nor in reducing the frequency of lupus flares (28). There was also a study aimed to examine whether vitamin D supplementation in adolescence can influence adult onset of SLE, but no associations were found (34).

In addition, one study suggests that a high level of vitamin D can also help against fatigability in SLE patients (35). However, several other studies have shown that vitamin D supplementation does not improve fatigue in SLE patients (36,37).

Vitamin E, especially combined with omega-3 PUFA from fish oil, decreases levels of inflammatory cytokines, IL-2, IL-4 and TNF-α (6).

Vitamin C, an important antioxidant, prevents oxidative stress, reduces inflammation and lowers antibodies levels (anti-dsDNA, IgG), also preventing cardiovascular complications. Therefore, vitamin C should be supplemented in SLE patients diet at a maximum dose of 1 g/day, or in combination with vitamin E (vitamin C; 500 mg and vitamin E; 800 IU), due to its synergic action. Orange juice, tangerine, papaya and broccoli are excellent sources of vitamin C (6).

Retinoic acid, a vitamin A metabolite, has antineoplastic effect, inhibits Th-17 and reduces antibodies level, and therefore diet supplementation should include 100,000 IU vitamin A daily, with caution not to exceed this dosage, causing symptoms that range from dry skin, alopecia, headache, nausea and anemia, to death (6,21). Natural sources of vitamin A include mainly carrots and pumpkins, but it can be found in spinach, sweet potato and liver (6).

The vitamin B complex helps reduce the level of TG and LDL-C, and improves clinical symptoms in SLE. The best food supply for vitamin B is red meat, liver and fortified cereals, but it can also be found in chicken, salmon, sardine, nuts, eggs, banana, and avocado (6).

Polyphenols, isoflavones

Little information is known about polyphenols, bioactive components of a wide range of food, such as fruits and vegetables, red wine and tea, with a highly beneficial impact on the gut microbiota (12).

A recent study was set to determine the associations between polyphenols intake and fecal microbiota in patients with SLE and in controls (38).

Flavonoids represent the largest class of polyphenols and are classified in six subclasses including flavones, flavonones, flavonols, chalcones, anthocyanins and isoflavonoids. These incredible health boosters, apart from promoting a better immune response, have a well-established antioxidant and antimicrobial effect, as well as an antiaging role (39).

The main food that provide an intake of flavones include various fruits and vegetables (oranges, lettuce, watermelon, kiwi, tomato, apple, lentils, celery). The study of Cuervo et al (38), showed oranges provide the main amount of flavonones in SLE patients, while dihydrochalcones were ensured merely from apple intake. Dihydroflavonols came predominantly from consumption of red wine, whereas flavonols intake was due to tea, apple, spinach, walnut, white bean, lettuce, asparagus, broccoli, green bean and tomato. The study points out that a well-balanced diet, with a high intake of apples and oranges, as well as other fruits and vegetables rich in flavonoids, has been associated with the fecal levels of beneficial microorganisms (Lactobacillus, Blautia and Bifidobacterium) in SLE patients (38).

Isoflavones are estrogen-like nutrients, extracted from soybean, which have an antiinflammatory and antioxidant effect, reduce proteinuria and antibodies production, and can decrease IFN-Υ secretion (39). Other sources of isoflavones are black beans, olive oil and cereals (6).

Minerals

Special attention is to be paid to mineral intake since it is best to restrict consumption of some minerals such as zinc and sodium. It was emphasized that a decrease in zinc can improve symptoms in SLE patients and also reduce levels of antibodies (anti-dsDNA) (22). Zinc is particularly found in mollusks, but also in milk, soybean and spinach (6).

Sodium intake not only has no beneficial effect but also exacerbates renal dysfunction (40) in SLE patients, who should be advised to reduce salt and condiments from their diet. For these patients, sodium intake should be less than 3 g/day (41).

Selenium has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and can be added to patients' diet from consumption of nuts, whole cereals, eggs and ricotta (6). Calcium levels can be increased by the intake of diary, spinach, sardine or soybean, but oral supplements are also of use (Calcium >1500 mg daily, in addition to vitamin D; 800 IU vitamin D) in order to help prevent bone mass loss. Iron should only be used in anemic patients, to maintain a balance, since excess of iron can aggravate renal impairment in SLE patients and a deficiency exacerbates clinical symptomatology (6).

Aminoacids and other nutrients

Conflicting results have emerged concerning L-canavanine, a non-proteicaminoacid that controls antibodies synthesis and has a suppressive effect on T cells. The main source for L-canavanine are soybean and alfalfa, but it can also be extracted from onion (6). Some studies revealed that alfalfa sprouts induced lupus-like syndrome in otherwise healthy individuals and reactivated SLE both clinically and serologically in patients with inactive disease (42).

Taurine, found in meat, eggs and oyster, is a β aminoacid which regulates the immune response, decreases the oxidative stress and lowers the level of inflammatory cytokines and lipids (6).

Royal jelly, rich in aminoacids and vitamins, could supplement SLA patients' diet, due to its hypocholesterolemic, anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects (43).

Over the past decades, curcumin, a polyphenol extracted from a spice called Curcuma longa, also known as turmeric, has been highly studied in both pre-clinical and clinical trials (44). Due to its well-established anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, hypoglycemic and wound healing effects (45,46) curcumin has been used in a wide range of inflammatory diseases including the dermatological spectrum (psoriasis, vitiligo, SLE- lupus nephritis, oral lichen planus) (44).

The recommended dosage for lupus nephritis is 500 mg daily for 3 months, which leads to a reduction in proteinuria, hematuria and blood pressure in SLE patients who have relapsing of intractable lupus nephritis (47). Curcumin modulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules and CRP, thus eliciting a beneficial anti-inflammatory effect in arthritis, by reducing pain and CRP level, and increasing the walking distance, at a dosage of 200 mg daily for 3 months (48,49). When used in combination with celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor), the effect is synergic (50). The dosage for SLE ranges from 100–200 mg daily to 4.5 g/day, but curcumin supplementation is considered safe in up to 12 g daily (44).

Discussion

Patients' lifestyle may adjust the course of SLE, because diet or psychological stress are involved in the modulation of cutaneous inflammation (51). By small improvements in diet, the state may lower the costs arising from hospitalization and administration of drugs to patients with SLE (52).

Taking into account the results of the ample studies that we have discussed, we support the importance of diet on systemic lupus and we propose a dietary plan. Therefore, diet for patients with lupus should be personalized. In the era of expensive biologicals or biosimilars (53,54) diet could improve clinical status of patients with SLE in a cost-effective way.

Caloric restriction is beneficial to the immune system, it is positively related to disease activity and it lowers the level of fatigue. Diets with higher level of PUFA reduce the risk of fetal loss and symptoms in women with SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome, and it may also have a positive impact on overall clinical status. Omega-3 reduces cardiovascular risk, while omega-6 PUFA may exacerbate SLE activity. Flaxseed oil can lower serum creatinine and fish oil reduce TG and increase HDL-C. Moderate protein intake improves renal function. Fibers regulate hyperlipidemia, lower blood pressure and CRP. Vitamins are also important, vitamin D deficiency is associated with more severe disease activity, vitamin C prevents cardiovascular complications, reduces inflammation and antibodies level, retinoic acid also reduces antibodies level and vitamins from B complex improves clinical symptoms, reduce TG and LDL-C. Flavonoids reduce proteinuria, antibodies production and INF-γ production. Regarding minerals, it's best to restrict zinc and sodium consumption, and also excess of iron. Curcumin (turmeric) is beneficial to lupus nephritis.

Patients with SLE should introduce in their diet whole grains instead of refined ones (also adding barley, quinoa and rye), sea salt instead of refined salt, and instead of sugar, patients should use rice, barley, or maple syrup. Fresh vegetables should be consumed daily, as well as at least one fruit per day. Fresh fish also play a beneficial role in SLE patient's diet and should be added to the personalized diet, as well as cold pressed oil. Patients can supplement the diet with flaxseeds, pumpkins, carrots, nuts, oranges or apples.

In conclusion, the paper clearly emphasizes the beneficial role of personalized diet in patients with SLE, and the information presented could be successfully used in our daily practice, helping patients understand the dietary impact on their disease and establishing individualized diet plans.

Proper diet in SLE can help preserve the body's homeostasis, increase the period of remission, prevent adverse effects of medication (especially systemic corticotherapy), and improve the patient's physical and mental well-being.

However, further prospective studies are needed on large cohorts of patients to quantify the long-term impact of diet on SLE, and we believe this study is useful starting point in this direction.