뇌척수액(CSF)의 흐름 경로는 중추신경계의 기능과 항상성 유지에 핵심적이며,

전통적인 순환 경로와 최근 발견된 글림프계(glymphatic system)로 구분됩니다.

대학원 수준에서의 심화된 설명은 다음과 같습니다:

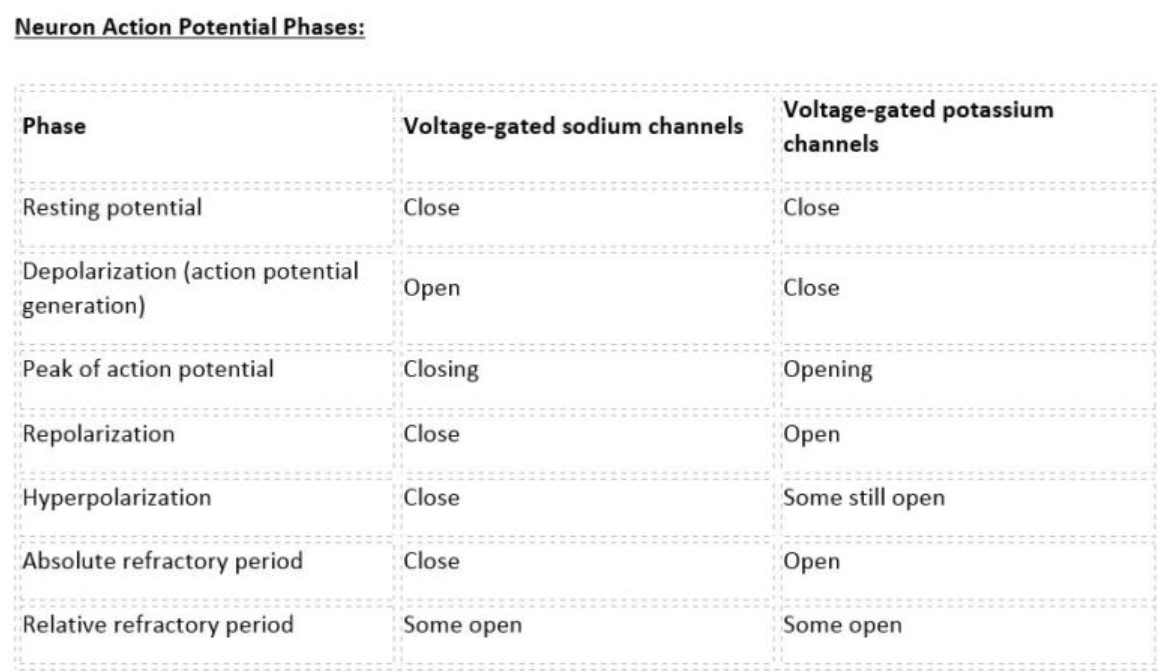

1. 전통적 뇌척수액 순환 경로

(1) 생성 (Production)

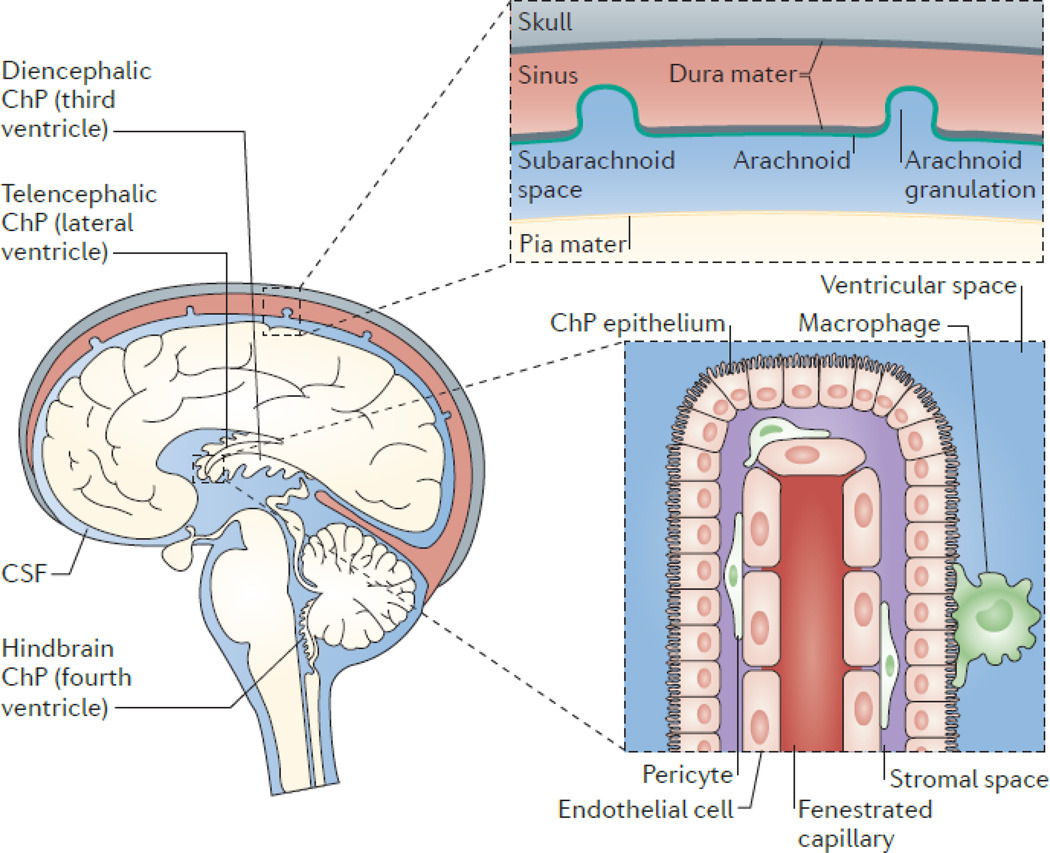

- 주 생성 부위: 뇌실의 맥락총락(choroid plexus)에서

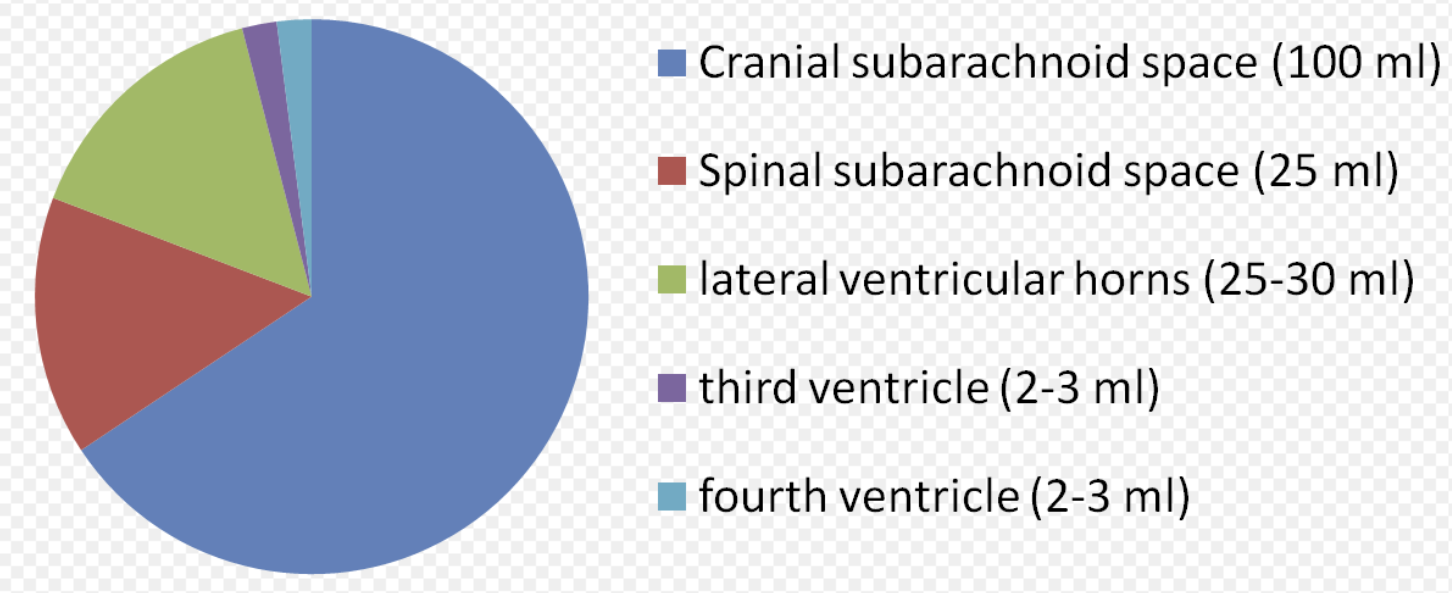

- 하루 약 500mL 생성 (총량 150mL로 3-4회/일 교체).

(2) 뇌실계 순환 (Ventricular System)

- 측뇌실(Lateral ventricles) → 실간공(Interventricular foramen of Monro) 통해 제3뇌실(Third ventricle) 유입.

- 중뇌수도관(Cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius) 통해 제4뇌실(Fourth ventricle) 이동.

- 제4뇌실 출구:

(3) 지주막밑공간(Subarachnoid space) 확산

- 주요 지주막밑지(cisterns):

(4) 재흡수 (Reabsorption)

- **지주막과립(arachnoid granulations/villi)**을 통해 **상상시상정맥동(superior sagittal sinus)**으로 이동.

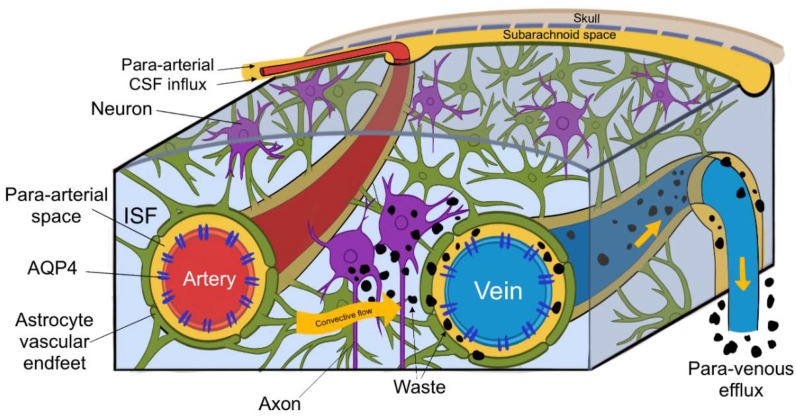

2. 글림프계(Glymphatic System) 경로

(1) 개요

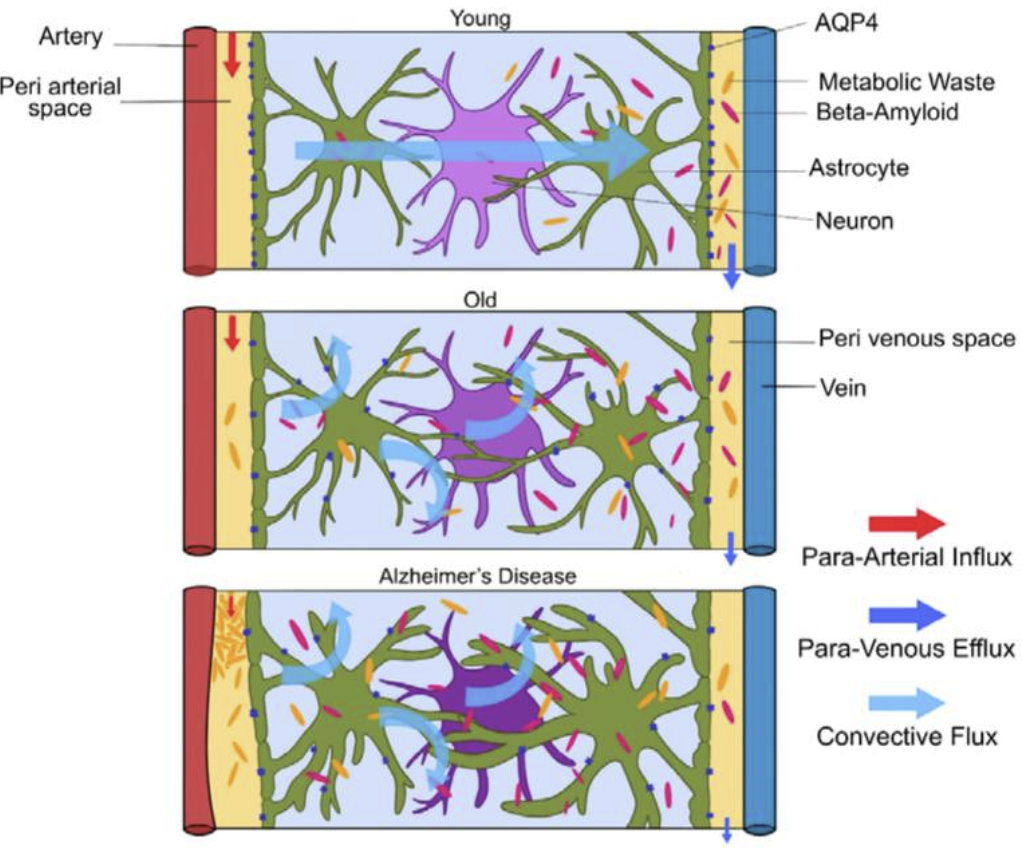

- 2012년 발견된 파라혈관(paravascular) 경로로, 주로 수면 중 활성화되어 대사 노폐물(beta-amyloid 등) 제거.

- 주요 구성 요소:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7698404/

(2) 작용 메커니즘

- CSF 유입: 경동맥을 따라 뇌실질 내 파라동맥 공간으로 유입.

- 간질액 교환: AQP4 채널을 통해 뉴런 간 간질액과 혼합.

- 노폐물 배출: 파라정맥 공간 → 뇌막림프관(meningeal lymphatics) → 경부림프절.

3. 순환 동력학 (Hydrodynamics)

- 주요 구동력:

4. 병리학적 연관성 (Clinical Correlations)

- 수두증(Hydrocephalus):

- 두개내압 상승(ICP↑): CSF 순환 장애 → 뇌탈출(herniation) 위험.

- 신경퇴행성 질환: 글림프계 기능 저하 → beta-amyloid 축적(알츠하이머병).

5. 최신 연구 동향

- 고해상도 영상기술: 7T MRI를 이용한 실시간 CSF 흐름 시각화.

- 약물전달 시스템: CSF 경로 활용한 중추신경계 표적 치료제 개발(예: 척추강내 주사).

이와 같이 CSF 순환은 복잡한 생역학적 메커니즘을 바탕으로 뇌-척수의 항상성을 유지하며, 임상적 및 연구적 중요성이 큽니다.

Dual function of the choroid plexus: Cerebrospinal fluid production and control of brain ion homeostasis

Author links open overlay panelNanna MacAulay, Trine L. Toft-Bertelsen

Show more

Add to Mendeley

Share

Cite

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2023.102797Get rights and content

Under a Creative Commons license

Open access

Highlights

- •

- •

- •

- •

- •

Abstract

The choroid plexus is a small monolayered epithelium located in the brain ventricles and serves to secrete the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that envelops the brain and fills the central ventricles. The CSF secretion is sustained with a concerted effort of a range of membrane transporters located in a polarized fashion in this tissue. Prominent amongst these are the Na+/K+-ATPase, the Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1), and several HCO3− transporters, which together support the net transepithelial transport of the major electrolytes, Na+ and Cl−, and thus drive the CSF secretion. The choroid plexus, in addition, serves an important role in keeping the CSF K+ concentration at a level compatible with normal brain function. The choroid plexus Na+/K+-ATPase represents a key factor in the barrier-mediated control of the CSF K+ homeostasis, as it increases its K+ uptake activity when faced with elevated extracellular K+ ([K+]o). In certain developmental or pathological conditions, the NKCC1 may revert its net transport direction to contribute to CSF K+ homeostasis. The choroid plexus ion transport machinery thus serves dual, yet interconnected, functions with its contribution to electrolyte and fluid secretion in combination with its control of brain K+ levels.

- 뇌실 주위 신경총은 뇌척수액(CSF)을 분비하는 역할을 합니다.

- •CSF는 기존의 삼투에 의해 생성되는 것으로 보이지 않습니다.

- •CSF 분비는 상피를 통한 Na+와 Cl-의 수송으로 발생합니다.

- •Na+/K+-ATPase는 CSF K+ 항상성의 장벽 매개 조절에 핵심적인 역할을 합니다.

- •NKCC1은 특정 조건 하에서 CSF K+ 항상성에 기여할 수 있습니다.

요약

뇌실 주위 신경총은

뇌실에 위치한 작은 단층 상피 조직으로,

뇌를 감싸고 중앙 뇌실을 채우는 뇌척수액(CSF)을 분비하는 역할을 합니다.

이 조직에 편광 방식으로 위치한

다양한 막 수송체의 공동 노력으로 뇌척수액 분비가 유지됩니다.

그 중에서도 특히 중요한 것은

Na+/K+-ATPase,

Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter(NKCC1), 그리고

몇몇 HCO3− 수송체인데,

이것들이 함께 작용하여

주요 전해질인 Na+와 Cl−의 상피 내 수송을 지원함으로써

뇌척수액 분비를 촉진합니다.

또한,

맥락막 신경총은

뇌척수액의 K+ 농도를 정상적인 뇌 기능에 적합한 수준으로 유지하는 데

중요한 역할을 합니다.

뇌실막 Na+/K+-ATPase는

세포외 K+ 농도 상승([K+]o)에 직면했을 때

K+ 흡수 활동을 증가시키기 때문에,

장벽 매개 조절에 있어서 CSF K+ 항상성의 핵심 요소입니다.

특정 발달 또는 병리학적 조건에서,

NKCC1은 그 순 수송 방향을 되돌려 CSF K+ 항상성에 기여할 수 있습니다.

따라서,

맥락막 신경총 이온 수송 기계는

뇌의 K+ 수준을 조절하는 것과 함께 전해질과 체액 분비에 기여함으로써

상호 연결된 두 가지 기능을 수행합니다.

Graphical abstract

Keywords

Cerebrospinal fluid

Choroid plexus

Na+/K+-ATPase

Ionic gradients

Membrane transport

K+ homeostasis

Abbreviations

AE2

anion (Cl−/HCO3−) exchanger

AQP1

aquaporin 1

CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

DIDS

diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate

EM

electromicroscopy

ICP

intracranial pressure

ISF

interstitial fluid

[K+]CSF

K+ concentration in CSF

[K+]ISF

K+ concentration in ISF

[K+]o

extracellular K+ concentration

[K+]plasma

K+ concentration in plasma

KCCs

K+,Cl− cotransporters

LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

NBCe2

Na+-driven bicarbonate cotransporter

NCBE

Na+-driven chloride bicarbonate exchanger

NKCC1

Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter

P

postnatal day

SPAK

SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase

TRPV4

transient receptor potential vanilloid channel 4

WNK

with no lysine

1. Introduction

Our brain is bathed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that protects the brain from mechanical insults, serves as the intracerebral dispersion route for signaling molecules and nutrients, and acts as a conduit for waste clearance [1,2]. The CSF is thus indispensable for normal brain function. Dysregulation of CSF homeostasis occurs in many pathologies and may lead to debilitating, or even fatal, brain water accumulation and ensuing elevation of the intracranial pressure (ICP), which represents a towering neurosurgical challenge. Hydrocephalus (‘water in the head’) may arise as a congenital condition, following a hemorrhagic or infectious event, or in the elderly population as normal pressure hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus is thus one of the most common neurosurgical disorders worldwide with a global prevalence of 85/100,000 (even higher in pediatric and elderly populations) [3] and thus a significant health care burden. There is no cure for hydrocephalus, which is traditionally treated by surgical implantation of a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (diversion of excess ventricular fluid to the peritoneal cavity) [4], endoscopic third ventriculostomy (puncture of the third ventricle floor) [5], or even choroid plexus cauterization [6]. The current treatment of elevated ICP is thus limited to invasive surgical methodology based on hydro-mechanical principles and associated with many complications and semi-acute surgical shunt revisions [7,8], in part due to our limited knowledge about the molecular mechanisms underlying CSF secretion and therefore a lack of rational pharmaceutical targets.

1. 서론

우리의 뇌는

뇌척수액(CSF)에 의해 보호받고 있습니다.

뇌척수액은

기계적 자극으로부터 뇌를 보호하고,

신호 전달 분자와 영양분을 뇌 내로 분산시키는 경로 역할을 하며,

따라서

뇌척수액은 정상적인 뇌 기능에 필수적입니다.

뇌척수액 항상성의 조절 장애는 많은 병리학에서 발생하며,

이로 인해 뇌수 축적과 그에 따른 두개 내압(ICP) 상승으로 인한

쇠약 또는 심지어 사망에 이를 수 있으며,

이는 신경외과에서 가장 어려운 문제 중 하나입니다.

뇌수종('머리에 물이 차는 병')은 선천성 질환으로 출혈성 또는 감염성 질환에 이은 후 발생하거나, 정상압 뇌수종으로 노인 인구에서 발생할 수 있습니다.

따라서

뇌수종은 전 세계적으로 가장 흔한 신경외과 질환 중 하나이며,

100,000명당 85명(소아 및 노인 인구에서는 더 높음)의 유병률을 보이며,

따라서 상당한 의료 부담이 됩니다. [3]

뇌수종에 대한 치료법은 없습니다.

전통적으로 뇌수종은

심실-복막 단락술(과도한 뇌척수액을 복막강으로 배출하는 수술) [4], 내시경 제3뇌실조루술(제3뇌실 바닥을 뚫는 수술) [5], 또는 맥락막 신경총 소작 [6]으로 치료합니다.

따라서

현재 고혈압성 뇌척수액증의 치료는

수력역학 원리에 기반한 침습적 수술 방법론으로 제한되어 있으며,

많은 합병증과 준급성 수술적 션트 개조[7,8]와 관련되어 있습니다.

이는 부분적으로 뇌척수액 분비의 기초가 되는 분자 메커니즘에 대한 제한된 지식과 합리적인 약학적 표적의 부족 때문입니다.

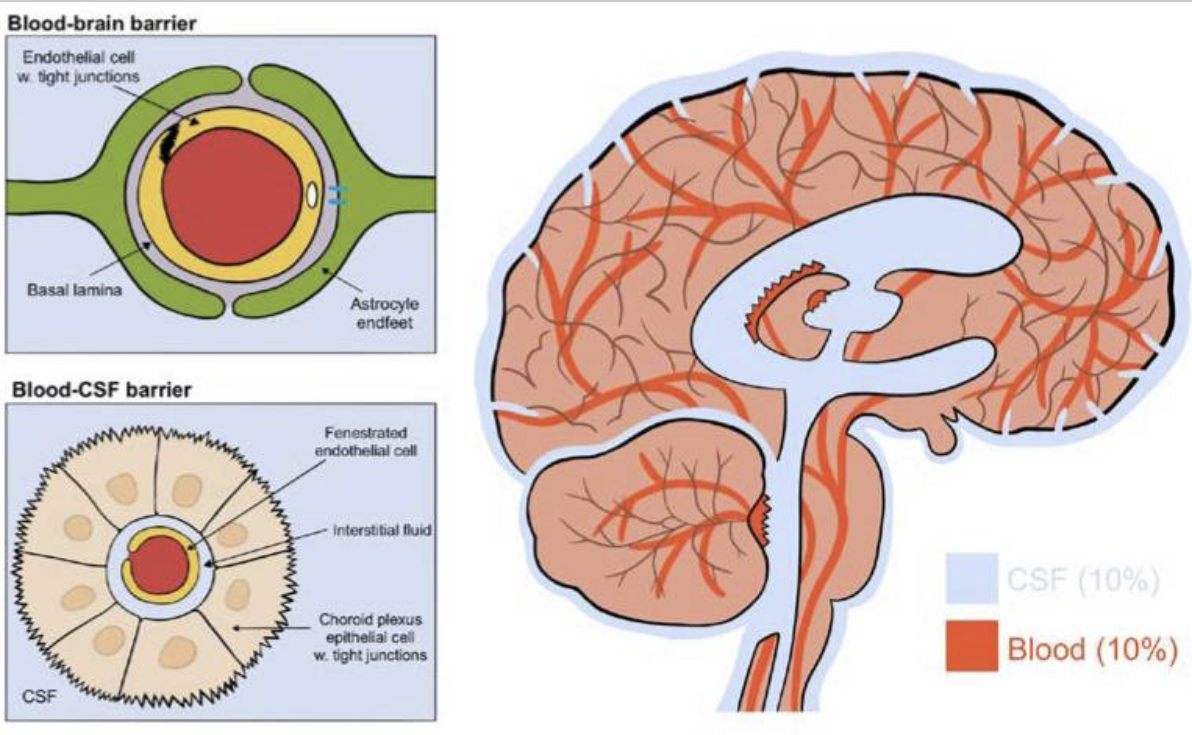

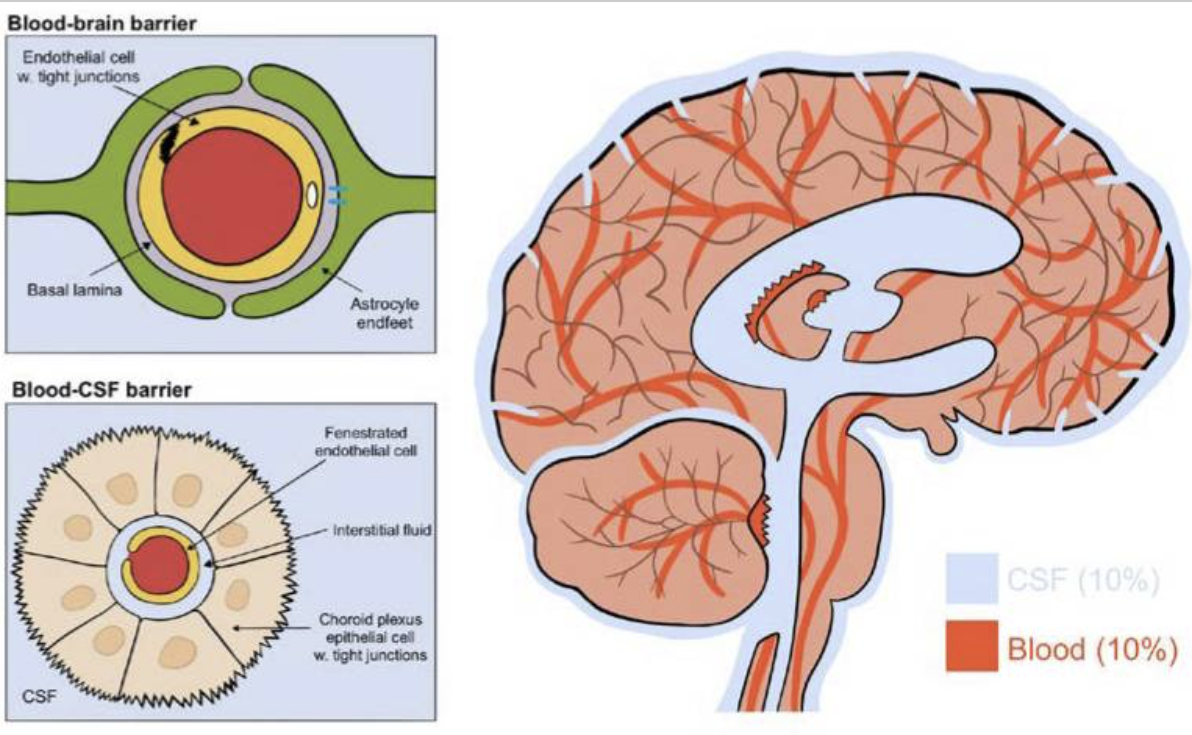

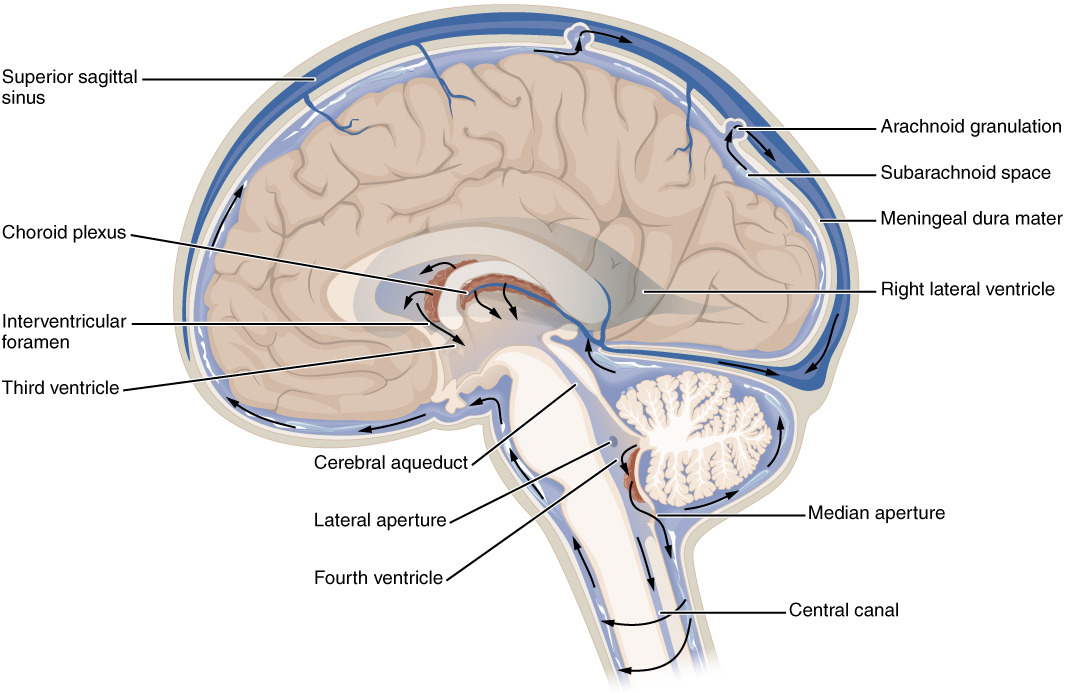

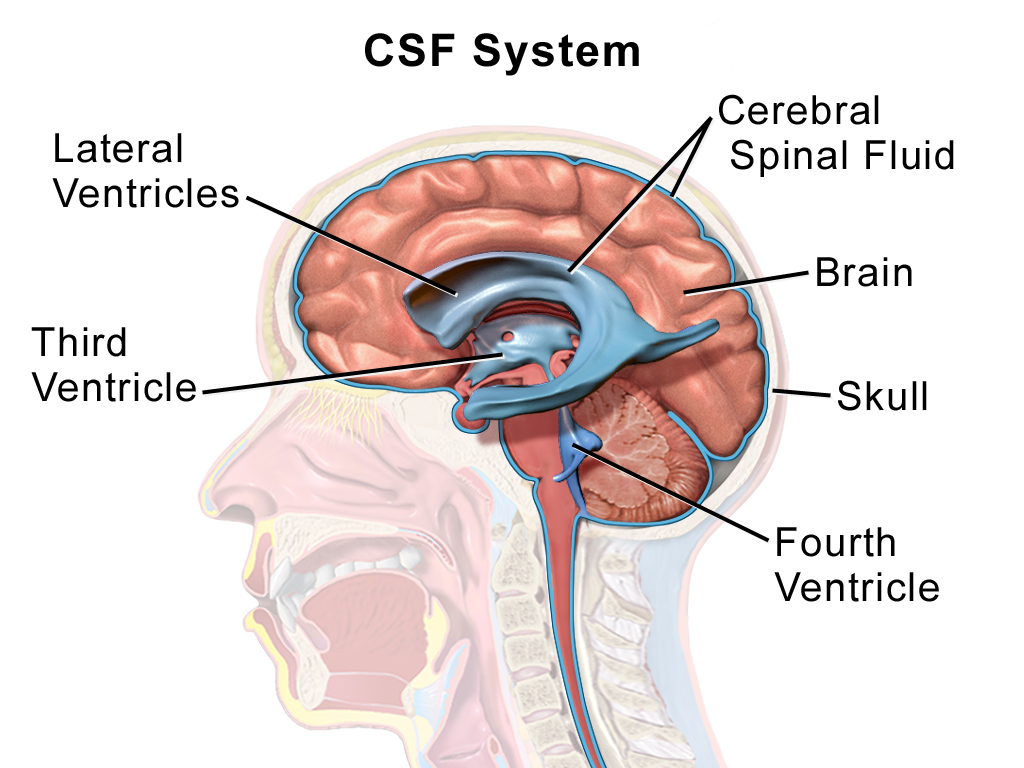

2. CSF flow through the ventricular system

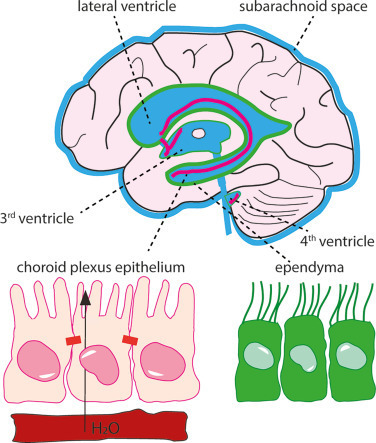

In the adult human, approximately 500 ml CSF is secreted daily from the vasculature and into the brain. The CSF circulates through the ventricular system, which consists of the two lateral ventricles that connect to the third ventricle via the foramina of Monro and further to the fourth ventricle via the aqueduct of Sylvius, Fig. 1. The fluid is propelled by the hydrostatic pressure that comes with its continued secretion, by the respiratory cycle and arterial pulsations, and possibly by directional beating of the cilia of the ependymal cells lining the ventricles and the aqueduct [9,10], prior to entering the spinal canal or the subarachnoid space. The site of CSF reabsorption was historically assigned to the arachnoid granulations or their smaller counterparts, the arachnoid villi, which protrude from the subarachnoid space into the dural venous sinuses. However, this proposed route of CSF egress may, rather, serve as an additional drainage pathway under conditions of raised intracranial pressure [11], since they are nonexistent in human fetuses and lower animals [12], [13], [14]. Recent evidence suggests that CSF drainage mainly occurs along cranial nerve sheaths, especially those of the olfactory and optic nerves and those of the spine, to extracranial lymph nodes [14], [15], [16].

2. 뇌실계를 통한 뇌척수액의 흐름

성인 인간의 경우,

매일 약 500ml의 뇌척수액이

혈관을 통해 뇌로 분비됩니다.

뇌척수액은

제3뇌실과 연결된 두 개의 측두뇌실과, 몬로공(foramina of Monro)을 통해

제4뇌실로 연결되는 실비아관(aqueduct of Sylvius)을 통해 순환합니다(그림 1).

이 액체는

지속적인 분비, 호흡 주기, 동맥 맥동,

심실과 수로를 감싸고 있는 뇌배엽 세포의 섬모의 방향성 박동에 의해 생성되는

정수압에 의해 추진됩니다.

CSF 재흡수 부위는

역사적으로 지주막하 공간에서 경막정맥동으로 돌출되어 있는 지주막 소포 또는

그보다 작은 지주막 소포에 할당되어 왔습니다.

그러나,

이 CSF 유출 경로는 두개 내압이 상승하는 조건에서

추가적인 배액 경로로 작용할 수 있습니다 [11].

인간 태아와 하등 동물에게는 존재하지 않기 때문입니다 [12], [13], [14].

최근의 증거에 따르면,

뇌척수액의 배액은

주로 두개골 신경초, 특히 후각신경과 시신경의 신경초,

리고 척추의 신경초를 따라 두개외 림프절 [14], [15], [16]로 흐른다고 합니다.

Fig. 1. The CSF-containing ventricular system and choroid plexus. The fluid-filled ventricular system and subarachnoid space are marked in blue with indication of the lateral, 3rd, and 4th ventricle. The choroid plexus is located in each of the ventricles and marked in pink, whereas the ependymal cell layer lining the ventricles is marked in green. Insets illustrate (left) the monolayer of choroid plexus epithelial cells (in pink) bordering on the vasculature (in red) with tight junctions illustrated as bars and (right) the ciliated ependymal cell layer (in green).

그림 1. CSF를 포함하는 심실 시스템과 맥락막. 체액이 채워진 심실 시스템과 지주막하 공간은 측면, 제3, 제4 심실을 나타내는 파란색으로 표시되어 있습니다. 맥락막 신경총은 각 심실에 위치해 있으며 분홍색으로 표시되어 있고, 심실을 감싸고 있는 상피세포층은 녹색으로 표시되어 있습니다. 삽입 그림은 (왼쪽) 맥락막 신경총 상피세포의 단일층(분홍색)이 혈관(빨간색)에 접해 있는 모습을 막대 모양으로 표시된 단단한 접합부로 보여주고, (오른쪽) 섬모 상피세포층(녹색)을 보여줍니다.

3. CSF secretion by the choroid plexus

3.1. CSF secretion takes place via the choroid plexus

The CSF originates, for the main part, from the highly vascularized frond-like structures protruding into each of the four ventricles; the choroid plexuses [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], with the larger fourth choroid plexus generating more than half of the CSF in dogs and monkeys [20,[22], [23], [24]]. This high-capacity fluid-secreting neuroepithelium arises from the neuroectoderm [25] and differentiates from neuroepithelial and rhombic lip lineages along the dorsal axis of the neural tube [26]. The choroid plexus resembles other epithelia with a highly folded basolateral membrane, a luminal membrane covered in short microvilli (increasing its surface area up to 15-fold [27], [28], [29]), high density of mitochondria [27,[30], [31], [32]], interconnections by tight junctions located towards the luminal aspect [33,34], and expression of a variety of membrane transport mechanisms [35], Fig. 1. A concerted effort of a selection of these transport mechanisms underlies the electrolyte and fluid transport across the choroid plexus epithelium that constitutes the CSF secretion by this tissue. Notably, since the ependymal cells constituting the ventricular lining do not serve as a barrier function, due to the ependymal absence of tight junctions [33,[36], [37], [38]], the CSF is in continuum with the interstitial fluid (ISF) surrounding nerve and glia cells of the brain parenchyma [38,39], Fig. 1. Therefore, ion transporters in the choroid plexus may directly influence brain ion homeostasis and nerve function, in addition to their cardinal roles in CSF secretion.

3. 맥락막하수체에 의한 뇌척수액 분비

3.1. 뇌척수액은 맥락막하수체를 통해 분비됩니다.

CSF는

주로 네 개의 심실로 돌출된 혈관이 발달된 잎 모양의 구조물인 맥락막 신경총 [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]에서 유래하며,

그 중에서도 네 번째로 큰 맥락막 신경총이 개와 원숭이의 CSF의 절반 이상을 생성합니다 [20,[22], [23], [24]].

이 대용량 유체 분비 신경상피는

신경관 [26]의 등축을 따라 신경상피 및 능형 입술 계통과 분화합니다.

맥락막 신경총은

다른 상피 조직과 유사하게,

접힌 기저측막, 짧은 미세 융모로 덮인 내강막(표면적을 최대 15배까지 증가[27], [28], [29]), 고밀도 미토콘드리아[27,[30], [31], [32]]를 가지고 있습니다.

관 내측을 향한 단단한 접합부에 의한 상호 연결 [33,34], 그리고

그림 1. 이러한 수송 메커니즘의 선택적 협동 작용은

이 조직에 의한 CSF 분비를 구성하는 맥락막 상피를 가로지르는 전해질과 체액 수송의 기초가 됩니다.

특히,

심실 내벽을 구성하는 뇌실막 세포는

뇌실막에 결합 조직이 없기 때문에 장벽 기능을 하지 않습니다[33,[36], [37], [38]],

따라서

뇌실액은

뇌실질 내의 신경과 신경교 세포를 둘러싸고 있는

그림 1.

따라서,

맥락막의 이온 수송체는

뇌척수액 분비에 있어 중요한 역할을 하는 것 외에도

뇌 이온 항상성과 신경 기능에 직접적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

3.2. CSF secretion takes place independently of conventional osmosis

The CSF does not originate from ultrafiltration across the choroid plexus from the plasma [19,[40], [41], [42]] and does not appear to be generated by conventional osmosis across the choroid plexus epithelium: a required osmotic gradient is virtually absent across this tissue [29], as well as in the inter-microvillar spaces at the surface of the choroid plexus [29] and in the lagunas within the choroid plexus epithelial foldings [43], for review, see [20]. In addition, CSF secretion readily takes place in the absence of – and even against – osmotic gradients [29,[44], [45], [46], [47]], for review, see [20]. These are features that are shared with a range of other fluid-secreting epithelia [48], [49], [50] and suggest that CSF is generated by active transport across the choroid plexus epithelium. The absence of osmotic driving forces across the choroid plexus epithelium and the ability of the tissue to generate CSF independently of such an osmotic gradient align with CSF secretion occurring nearly [51] or completely (Jensen et al., our unpublished data) independently of the water channel aquaporin 1 (AQP1) that is highly expressed exclusively in the luminal membrane of choroid plexus [52,53]. People deficient in AQP1, accordingly, report no neurological deficiencies [54,55].

3.2. CSF 분비는 기존의 삼투와 독립적으로 발생합니다.

CSF는

혈장으로부터 맥락막을 통한 한외여과로 인해 발생하지 않습니다. [19,[40], [41], [42]]

그리고

맥락막 신경총 상피를 가로지르는 일반적인 삼투에 의해 생성된 것으로 보이지 않습니다.

이 조직과 맥락막 신경총 표면의 미세소관 간 공간 [29], 그리고

맥락막 신경총 상피 주름 내부의 라구나 [43]에는

필요한 삼투 구배가 사실상 존재하지 않습니다.

자세한 내용은 [20]을 참조하십시오.

또한, CSF 분비는 삼투압 구배가 없을 때, 심지어 삼투압 구배가 있을 때에도 쉽게 일어납니다 [29,[44], [45], [46], [47]], 검토를 위해 [20]을 참조하십시오. 이 기능은 다양한 다른 유체 분비 상피 [48], [49], [50]와 공유되는 기능이며, 이는 뇌척수액이 맥락막 신경총 상피를 가로질러 능동 수송에 의해 생성됨을 시사합니다. 뇌실막 상피에 삼투성 구동력이 없고, 조직이 이러한 삼투성 구배와 관계없이 뇌척수액을 생성할 수 있는 능력은 뇌실막 상피의 내강막에서만 높게 발현되는 수로 아쿠아포린 1(AQP1)과 관계없이 거의 [51] 또는 완전히(Jensen et al., 미발표 자료) 뇌척수액 분비가 일어나는 것과 일치합니다[52,53]. 따라서 AQP1 결핍증 환자들은 신경학적 결손이 없다고 보고합니다 [54,55].

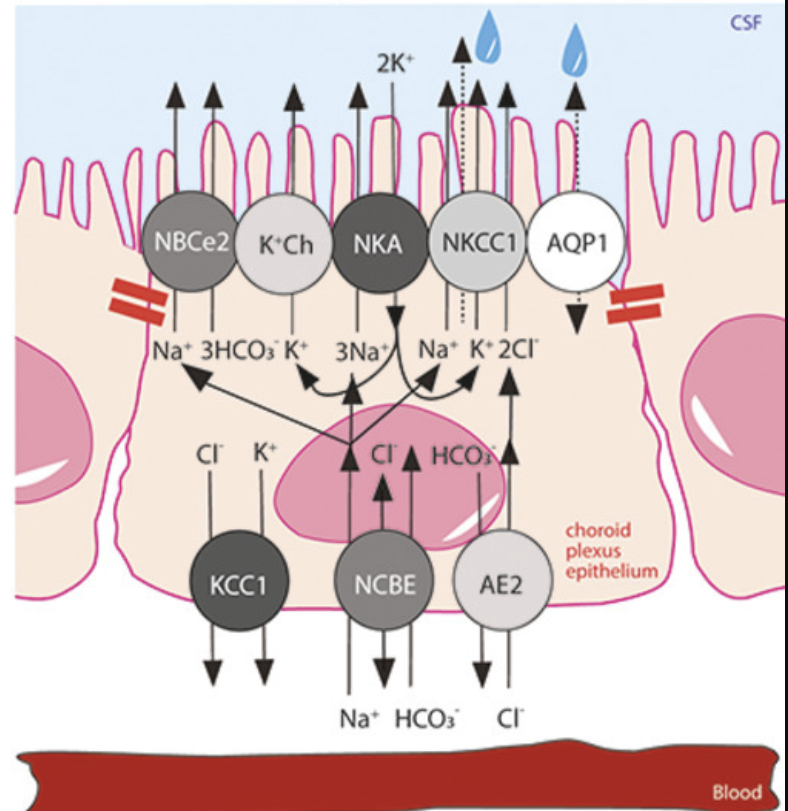

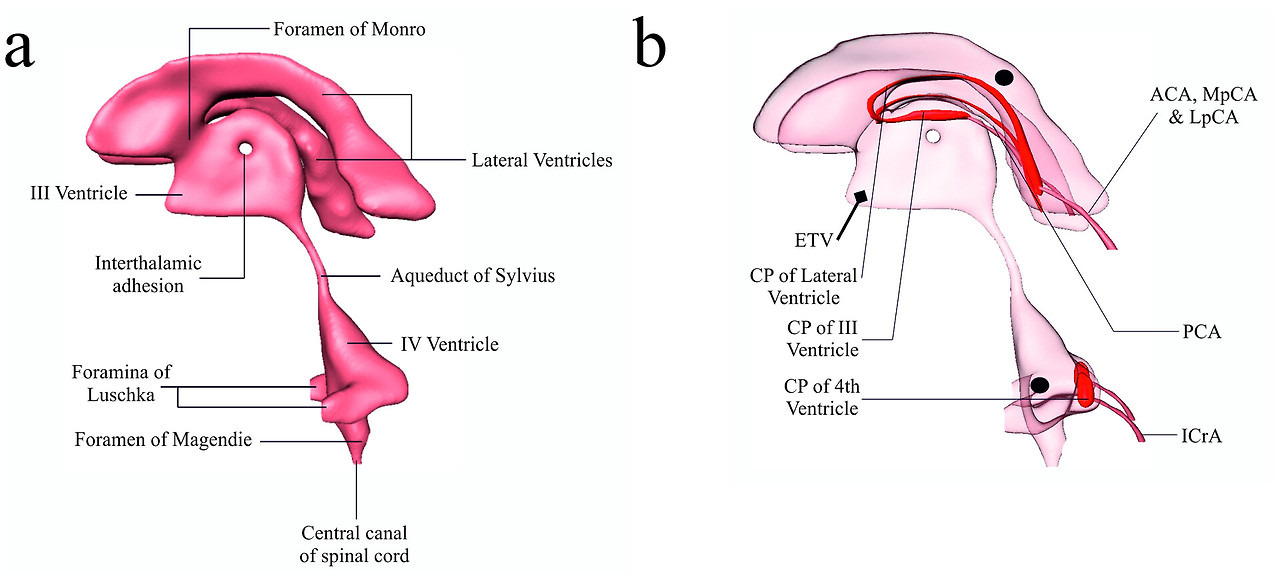

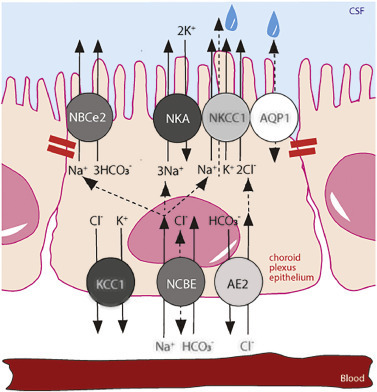

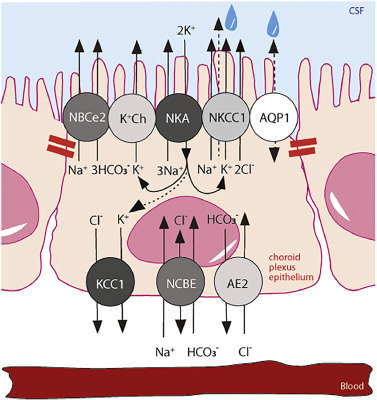

3.3. CSF secretion is sustained by choroid plexus ion transporters

As characteristic of other epithelia, the choroid plexus expresses an abundance of membrane transport mechanisms [35]. These are arranged in a polarized fashion to conduct the directional flux of ions and water that constitutes the CSF secretion, in addition to the multitude of other functions sustained by the choroid plexus as a gateway between the blood and CSF. Most prominent amongst the transport mechanisms involved in CSF secretion are the Na+/K+-ATPase of the α1 isoform and the Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) [29,56], both expressed in the luminal membrane of the choroid plexus [53]. Of the choroid plexus HCO3− transporters, the electrogenic Na+-driven bicarbonate cotransporter NBCe2 is detected in the luminal membrane, whereas the Na+-driven chloride bicarbonate exchanger NCBE and the anion (Cl−/HCO3−) exchanger AE2 represent the dominant basolateral HCO3− transporters [57], [58], [59], Fig. 2. Earlier immunohistochemistry has suggested the Na+/H+ exchanger [60] and various isoforms of the K+,Cl− cotransporters (KCCs) [61,62] as additional contributors to CSF secretion, which, however, was experimentally demonstrated to not be the case [29,63]. The latter finding aligns with no detectable KCC-mediated 86Rb+ efflux across the luminal membrane of excised choroid plexus in mice, rats, and pigs [29,63,64], negligible gene expression of KCC2-4 in choroid plexus, and the basolateral location of KCC1 [29,[63], [64], [65], [66]]. The contribution of the Na+/K+-ATPase, NKCC1, and NBCe2 expressed at the CSF-facing luminal membrane (see Fig. 2) is near equally distributed with 30–50 % reduction in the rate of CSF secretion upon their individual pharmacological inhibition [29]. The lack of specific inhibitors of the different HCO3− transporters have complicated elucidation of their individual contribution to CSF secretion, although research suggests NCBE and AE2 as responsible for Na+ and Cl− loading across the basolateral membrane and therefore expected contributors to electrolyte and water transport across this membrane [58,[67], [68], [69], [70]].

3.3. 뇌실질수분비(CSF)는 맥락막 신경총 이온 수송체에 의해 유지됩니다.

다른 상피 조직의 특징과 마찬가지로,

맥락막 신경총은 막 수송 메커니즘을 풍부하게 표현합니다 [35].

이러한 메커니즘은

혈액과 뇌척수액 사이의 관문으로서 맥락막 신경총이 유지하는 수많은 다른 기능 외에도,

뇌실질수분비(CSF)를 구성하는 이온과 물의 방향성 흐름을 유도하기 위해

편광 방식으로 배열되어 있습니다.

CSF 분비에 관여하는 수송 기작 중 가장 두드러지는 것은

α1 이소폼의 Na+/K+-ATPase와 Na+,K+,2Cl− 코트랜스포터 1(NKCC1)입니다[29,56].

이 두 가지 기작은

모두 맥락막의 내강막에서 발현됩니다[53].

맥락막 신경총 HCO3− 수송체 중에서 전기성 Na+-구동 중탄산염 공동수송체 NBCe2는

내강막에서 검출되는 반면,

Na+-구동 염화물 중탄산염 교환체 NCBE와 음이온(Cl−/HCO3−) 교환체 AE2는

지배적인 기저측 HCO3− 수송체를 나타낸다 [57], [58], [59], 그림 2.

이전의 면역조직화학은 Na+/H+ 교환기 [60]와 K+,Cl− 공동수송체(KCCs)의 다양한 이소형[61,62]이 뇌척수액 분비에 추가적인 기여를 한다고 제안했지만, 실험적으로 입증된 바는 없습니다[29,63]. 후자의 발견은 마우스, 랫트, 돼지의 절제된 맥락막 신경총의 내강막을 가로지르는 KCC 매개 86Rb+ 유출이 검출되지 않는다는 사실과 일치합니다 [29,63,64],

맥락막 신경총에서 KCC2-4의 무시할 만한 유전자 발현,

그리고 KCC1의 기저측 위치 [29,[63], [64], [65], [66]].

뇌척수액과 접촉하는 내강막(luminal membrane)에서 발현되는

Na+/K+-ATPase, NKCC1, NBCe2의 기여도는 거의 동일하게 분포되어 있으며,

이들의 개별적인 약리학적 억제에 따라

뇌척수액 분비율이 30-50% 감소합니다 [29].

다른 HCO3− 수송체의 특정한 억제제의 부재로 인해,

CSF 분비에 대한 개별적인 기여도를 밝히는 것이 복잡해졌지만,

연구에 따르면 NCBE와 AE2가 기저막을 가로지르는 Na+와 Cl−의 로딩을 담당하고,

따라서 이 막을 가로지르는 전해질과 물의 수송에 기여할 것으로 예상됩니다 [58,[67], [68], [69], [70]].

Fig. 2. Choroid plexus transport mechanisms implicated in CSF secretion. Polarized localization of select transporters in a choroid plexus epithelial cell with tight junctions marked with red bars. NBCe2, NCBE, AE2; bicarbonate transporters, AQP1; aquaporin 1, NKCC1; Na+,K+,2Cl− cotransporter 1, NKA; Na+/K+-ATPase. The net transport of the electrolytes Na+ and Cl− across the choroid plexus epithelium is marked with arrows from a basolaterally located transporter to those expressed in the luminal membrane. The dashed arrow through NKCC1, terminating in a water droplet, indicates the cotransporter-mediated water transport via NKCC1.

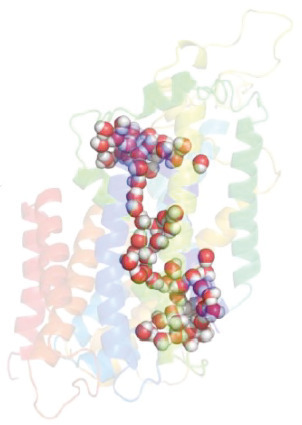

3.4. Transporter-mediated water transport supports CSF secretion

There is negligible or complete lack of AQPs in the basolateral choroid plexus membrane [52,53], which contributes the low osmotic water permeability across the entire epithelium [29,71]. Taken together with no apparent osmotic gradient across the choroid plexus or in the local compartments at the surface of the choroid plexus [29,43], in addition to the ability to secrete CSF against an osmotic gradient [29,[44], [45], [46], [47]], it remains puzzling how the fluid is secreted across the epithelium. Earlier in vitro experimentation has demonstrated water transport coupled directly to ion transport by a mechanism within a cotransport protein itself [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79]. Such coupling could present an alternative in which the local hyperosmolar compartment is shifted to a cavity inside the membrane transport proteins themselves [80]. Thereby these transporters translocate electrolytes and water in a manner independent of the prevailing osmotic gradient across the entire tissue [20]. For such a hyperosmolar-cavity model to be viable, there must, at least in some conformational state during the transport cycle, exist a continuous water-filled pore through the protein, as was recently demonstrated in a cryo-electromicroscopy (EM) structure of NKCC1 [81,82], Fig. 3. The authors of the cryo-EM structure proposed that such finding argued against NKCC1-mediated water transport [81,82], a statement which, however, originated in their assumed working model based on occlusion of the transported water molecules in a cavity within NKCC1 [80,83]. That model was discarded more than a decade prior to the publication of their study [84,85]. Transporter-mediated water transport has, accordingly, been demonstrated for NKCC1 and related cation-Cl− cotransporters in vitro [73,86] and in ex vivo choroid plexus from mouse, rat and salamander [29,63,72], and suggested to underlie the NKCC1-mediated contribution to the CSF secretion across the choroid plexus [29,63]. Whether this mode of water transport is supported by the remaining transporters involved in CSF secretion remains unresolved.

Fig. 3. Water permeation pathway observed in the cryo-EM structure of hNKCC1. Sphere representation of selected water molecules in an apparent permeation pathway containing nearly 100 water molecules though the hNKCC1, figure from Supplementary data in [81] with permission, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

4. Ion transport by the choroid plexus4.1. Na+ and Cl− transport across the choroid plexus associates with CSF secretion

Fluid secretion across various epithelia, including the choroid plexus, is generally coupled to net transport of Na+ across the tissue [87], [88], [89]. CSF was thus historically assumed to originate from osmotically obliged water transport following the Na+ flux [87,89,90]. Accordingly, the choroid plexus secretes Na+ from the blood to the ventricular compartment [68,87,[91], [92], [93], [94], [95]] as is evident with intravenous delivery of 24Na+ swiftly appearing at the surface of the exposed choroid plexus [19]. The 22/24Na+ transfer from blood to CSF is significantly faster than its blood-brain-barrier-mediated counterpart, due to a higher effective permeability of the choroid plexus [68], and is sensitive to the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide [87,91,93] to a similar extent as observed with the CSF secretion rate [96,97]. Together, these findings support that choroid plexus Na+ transfer may be considered a proxy of choroid plexus-mediated CSF secretion. As for Na+, its counter ion Cl− also swiftly appears in the CSF following intravenous delivery of 36Cl− [98]. The choroid plexus 36Cl− transfer from the blood to the ventricular compartment is partly reduced upon infusion of the NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide [99], the HCO3− transport inhibitor diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (DIDS) [97], or acetazolamide [98]. These are all well-established inhibitors of CSF secretion [56] and their similar effect on Cl− transport and CSF secretion supports implication of Cl− transport in CSF secretion. Taken together, net transchoroidal transport of the two main electrolytes, Na+ and Cl−, from the vasculature to the CSF supports CSF secretion across this tissue.

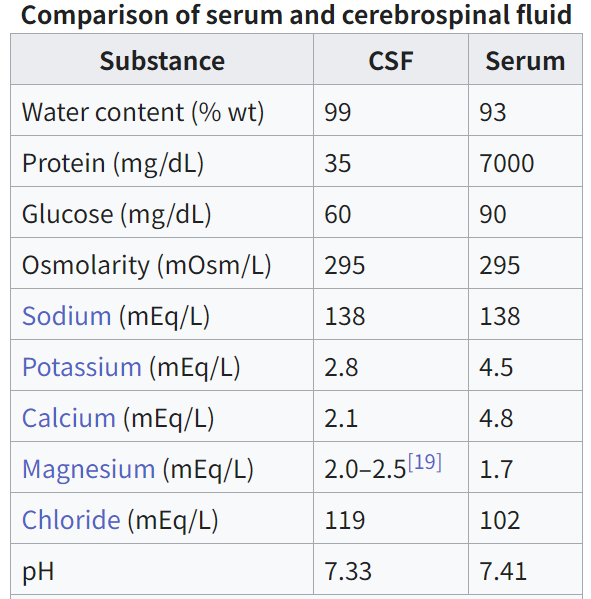

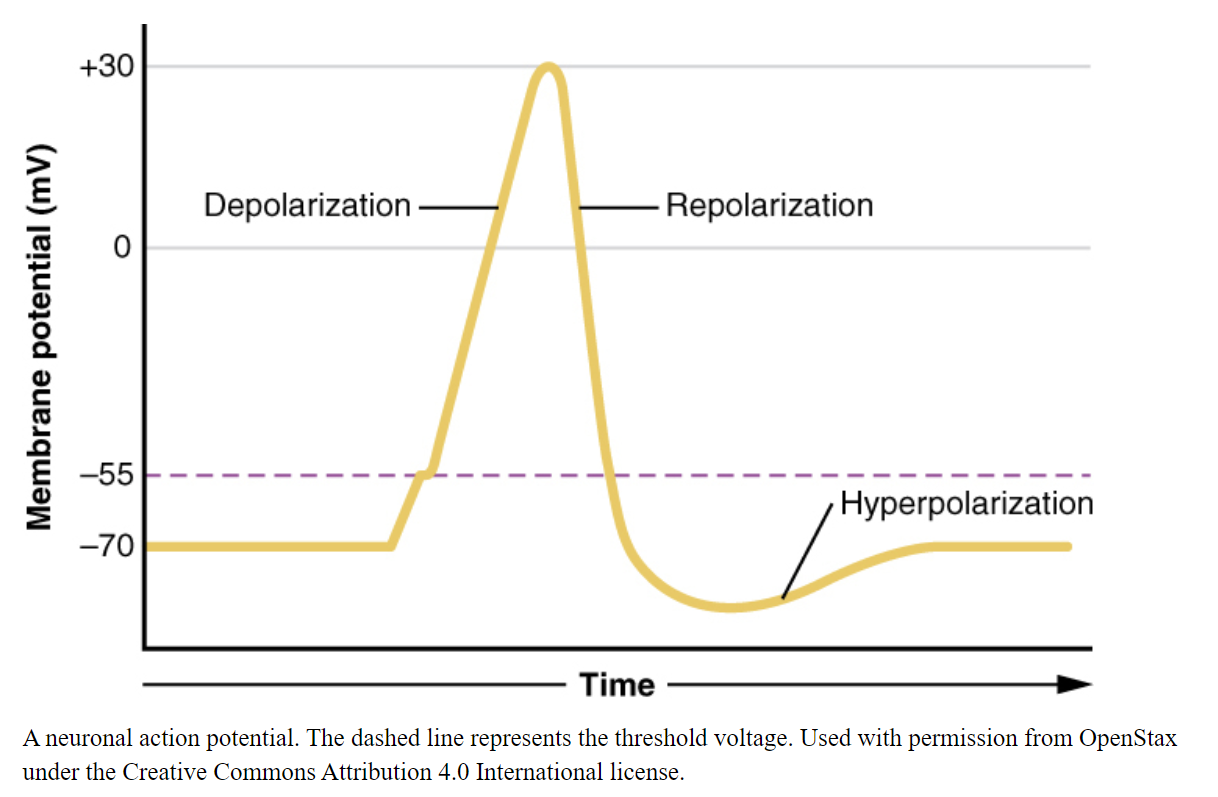

4.2. K+ transport across the choroid plexus membrane contributes to CNS K+ homeostasis

With the neuron resting membrane potential dictated predominantly by the equilibrium potential for K+, it follows that the neuronal excitability hinges directly on the K+ concentration in the ISF ([K+]ISF). [K+]ISF is therefore tightly regulated and remarkably stable around 3 mM in this fluid [100,101], starting in the gestational period in rats [37,102]. With the continuum between ISF and CSF [38,39], and hence between [K+]ISF and the K+ concentration in the CSF ([K+]CSF) [37], it follows that stable [K+]CSF is a physiological prerequisite for normal brain function. As for the [K+]ISF, the [K+]CSF has been measured to around 3 mM from gestation day 19 in rats and until postnatal day (P) 30 [37]. Other researchers have arrived at slightly higher (∼ 4 mM) values for [K+]CSF in newborn rabbits and rats [103], [104], [105], moderately higher (∼5 mM) values for [K+]CSF in newborn mice and rats [106], or much higher (∼10 mM) values for [K+]CSF in newborn mice [107]. Although it is not evident why this discrepancy arises, Jones and Keep [37] pointed to the K+ elevation occurring in plasma and CSF with hypoxia [108,109], especially so in young neonates and fetuses [110], in addition to potential K+ contamination from blood cells remaining in the CSF sample post-centrifuging. Jones and Keep circumvented such pitfalls by employing in situ ion-sensitive microelectrodes in addition to assuring mechanical ventilation of the anaesthetized dams while performing K+ determinations in the brains of attached fetuses [37]. It follows that their measurements demonstrated [K+]CSF of the usual ∼3 mM in rat fetuses, whereas similar studies performed without mechanical ventilation of the dams arrived at [K+]CSF of ∼8 mM in mice and rat fetuses [106,107]. In support of a component of hypoxia in these young rats, which may represent a confounding element, the latter study reported plasma [K+] of 15–25 mM [106], as opposed to the ∼4 mM observed by Jones and Keep [37].

It was earlier elegantly demonstrated in anaesthetized rabbits that the rate of K+ clearance from CSF to blood – the barrier clearance – increased steeply with increased [K+] in the ventricular perfusion fluid [111], Fig. 4. Notably, this barrier-mediated clearance was specific to K+, as barrier clearance of urea was unaffected by the elevated [K+]CSF, as was the rate of K+ penetration from the CSF into the brain parenchyma, and the transfer of K+ from blood to CSF [111]. Inclusion of the Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain in the perfusion fluid nearly abolished the elevated barrier-mediated K+ clearance observed at high [K+]CSF [111], suggesting that the choroid plexus Na+/K+-ATPase responded to elevated [K+]CSF with increased activity and thus K+ clearance from the CSF. This barrier-mediated K+ clearance was assigned directly to the choroid plexus in a series of ex vivo choroid plexus flux assays that demonstrated elevated K+ uptake with increased extracellular [K+] (= [K+]CSF) [112]. The majority of the choroid plexus K+ uptake was sensitive to ouabain, thus assigning the Na+/K+-ATPase as the key K+ uptake mechanism in rat choroid plexus [64,[112], [113], [114]]. These findings support a role for the choroid plexus in governing the [K+]CSF by its ability to clear K+ when the tissue is faced with elevated [K+]o, and the choroid plexus thus, together with the brain endothelium, ensures brain K+ homeostasis and neuronal function [101]. The choroid plexus Na+/K+-ATPase is located on the CSF-facing membrane [29,53,115], analogous to the localization in the brain-side membrane of the endothelial Na+/K+-ATPase [116,117], thereby both geared towards responding to – and removal of – elevated [K+] in the CSF and ISF, respectively. The Na+/K+-ATPase in both choroid plexus and capillary endothelial cells bears the ability to respond to elevated K+ with increased transport activity [112,117,118], partly due to their identical Na+/K+-ATPase isoform combination, with the catalytic α1 isoform combined with the accessory β1 or β3 isoform [29,35,117]. This α1β1(β3) combination is distinct from the glial α2β2 isoform expression and the neuronal α3β1 isoform expression [119,120], which present with kinetic properties geared towards proper physiological function of these brain cell types [121].

Fig. 4. The clearance of 42K+ from CSF into blood (barrier clearance) with varying [K+] in the ventricular/cisternal perfusion fluid in rabbits. Fluid of differing K+ concentrations (with inclusion of 42K+ as a tracer) was perfused into both lateral ventricles of anaesthetized rabbits and fluid subsequently collected from cisterna magna. Thereby the clearance of 42K+ from the CSF into the vasculature could be quantified and is illustrated as ‘barrier clearance’. The experimental point marked ‘ouabain’ indicates the K+ barrier clearance when the perfusion fluid contained 10−2 mM ouabain. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 3–4 experiments. Figure adapted from [111], with permission.

A smaller, ouabain-insensitive, K+ uptake is detectable in rat choroid plexus [64,[112], [113], [114]], which is assigned to NKCC1-mediated K+ uptake [64]. NKCC1, like other transport mechanisms, may transport its substrates in either direction. This feature is observed in excised rodent choroid plexus, which presents with a fraction of K+ uptake that is sensitive to the NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide [64] and thus assigned to inwards NKCC1-mediated K+ transport, as well as a fraction of K+ release that is bumetanide-sensitive [29,63,64,113] and thus assigned to outward NKCC1-mediated K+ transport. The net transport direction is determined by the transmembrane ion gradients, and may therefore change with ionic fluctuations in the CSF and/or the choroid plexus epithelial cells. At physiological K+ concentrations, the net transport rate of NKCC1 appears to be outwardly directed in acutely excised rodent choroid plexus, as demonstrated with fluorescent monitoring of the intracellular Na+ concentration upon inhibition of NKCC1 [29,63]. An outwardly directed NKCC1-mediated ion and fluid transport aligns with the well-established contribution of NKCC1 to CSF secretion and choroid plexus Cl− transfer from blood to CSF in rats, mice, and dogs [29,63,99,122,123]. The outwardly-directed net NKCC1 transport, in addition, is evident with its pharmacological inhibition leading to lowering of the ICP of healthy rats [29]. Nevertheless, in conditions with disturbed ion gradients across the choroid plexus, NKCC1 may revert its net transport direction [124], [125], [126], [127], [128] and thus contribute to K+ clearance from the CSF along with the Na+/K+-ATPase. Such reversal has been suggested for mechanically and enzymatically isolated choroid plexus epithelial cells briefly cultured prior to experimentation [129] and in neonate mice and rats [106,107]. However, a reversal of the NKCC1 net transport direction would generally require an elevation of the extracellular [K+]. CSF from patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage displayed a K+ concentration of ∼3 mM [130] and (Jensen et al., our unpublished data), which is not expected to suffice to promote a net inward NKCC1 transport direction. However, in the study by Sadegh and colleagues [130], the authors inexplicably divided the [K+]CSF with their paired, but unusually fluctuating (see [131] for comparison) CSF osmolality measurements. Their proposal of NKCC1 reversal, and thus inward transport, were based on these ‘normalized’ values rather than on the absolute [K+]CSF. In contrast, a sustained net outward NKCC1-mediated transport under conditions of brain hemorrhage is substantiated in animal models of intraventricular hemorrhage [123], subarachnoid hemorrhage [132], and traumatic brain injury [133], in which blockage of NKCC1 reduces the posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus.

Notably, the remarkable ability of the brain barrier transport mechanisms to keep [K+]CSF and [K+]ISF at the target 3 mM, even when the K+ concentration in the plasma ([K+]plasma) rises in the experimental animals [37,100,101,134], appears to develop with maturity. Although the [K+]ISF could be contained at 3 mM starting already at P1, the [K+]CSF increased with plasma hyperkalemia until the first weeks after birth, after which the [K+]CSF remained stable despite an imposed elevation of [K+]plasma [37]. This maturation of brain K+ homeostasis aligns with increased choroid plexus expression of the Na+/K+-ATPase and NKCC1 after birth [106,107,135], increased Na+/K+-ATPase activity as a function of development [135], and the ability to increase its transport rate when faced with a [K+]CSF challenge [112]. Embryonic choroid plexus-specific knockdown of NKCC1 in mice accordingly caused an increase in [K+]CSF [106], which suggests that NKCC1 may contribute to K+ clearance in the newborn mouse. The NKCC1-mediated K+ clearance could represent the smaller, ouabain-resistant, component of the K+ uptake observed in the developing rat choroid plexus [112].

NKCC1 mediates approximately two thirds of the K+ efflux across the luminal membrane of the choroid plexus epithelial cells in mice, rats and pigs [29,63,64]. The remaining fraction is assigned to channel-mediated K+ release [64,84,95]. The K+ conductance is a striking 10-fold higher in the luminal membrane than in that of the basolateral choroid plexus epithelial cell membrane [84,95]. It follows that the majority of the K+ transporting mechanisms reside in the luminal membrane, where the K+ influx notably matches the K+ efflux [95]. This molecular arrangement suggests a K+ cycle in which the K+ taken up by the Na+/K+-ATPase matches that released by NKCC1 and the variety of K+ channels residing in the luminal choroid plexus epithelial cell membrane [63,64,95,136], Fig. 5. In pathology or during development, when the Na+/K+-ATPase, aided by NKCC1, may support net K+ uptake into the choroid plexus epithelium to ensure stable [K+]CSF [106,107,111,112,130], the excess K+ must be released across the basolateral membrane into the interstitium and further cleared via the vasculature. With the sparse K+ channel expression and low K+ conductance across this membrane [95,136], K+ may be released across the basolateral membrane by KCC1-mediated K+ transport activity, Fig. 5, the function of which could be as mediator of K+ release from the choroid plexus epithelial cells to the vasculature during conditions of high [K+]CSF.

Fig. 5. Choroidal transport mechanisms implicated in choroid plexus K+ transport. Polarized localization of select transporters in the choroid plexus epithelium with tight junctions marked with red bars. NBCe2, NCBE, AE2; bicarbonate transporters, AQP1; aquaporin 1, NKCC1; Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter 1, KCC; K+/Cl− cotransporter 1, NKA; Na+/K+-ATPase, K+ Ch; K+ channels. The intracellular lines indicate a K+ shuttle with a cycling of K+ from the CSF to the cell interior via the Na+/K+-ATPase and a return to the CSF via NKCC1 and various K+ channels. A potential efflux across the basolateral membrane via KCC1 in situations of high ventricular [K+] is illustrated with an arrow connecting the K+ entry via the Na+/K+-ATPase to the exit route via KCC1. The dashed arrow through NKCC1, terminating in a water droplet, indicates the cotransporter-mediated water transport via NKCC1.

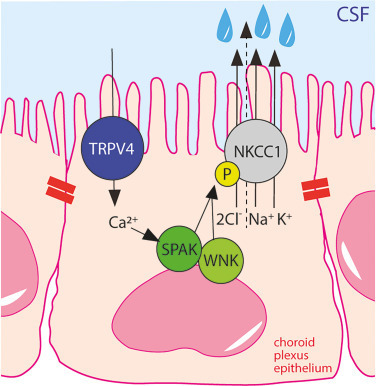

4.3. Ca2+-dependent regulation of CSF secretion

Although largely understudied, intracellular Ca2+ signaling takes place in the choroid plexus [137,138]. Ca2+ fluctuations may be observed with serotonergic receptor agonists or with activation of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) ion channel [137,139]. TRPV4 is amongst the highest expressed ion channels in the rodent choroid plexus and is located on the luminal membrane of the choroid plexus epithelial cells [139]. TRPV4 is a polymodal ion channel with several distinct manners of activation, i.e., cell swelling, temperature shifts, stretch and various lipid compounds [140]. Of the latter, the endogenous serum lipid lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) was recently demonstrated to interact directly with TRPV4 [141], leading to its channel activation and subsequent ventriculomegaly [139]. TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ influx increases the rate of CSF secretion, via with no lysine (WNK) kinase and SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) activation, and subsequent NKCC1 hyperactivation [139], Fig. 6. TRPV4 activation has, in addition, been demonstrated to modulate neighboring K+ and Cl− channels in a choroid plexus cell line [142]. Accordingly, inhibition of TRPV4 reduces the rate of CSF secretion in healthy rats [139] and abolishes ventriculomegaly in a genetic rat model of hydrocephalus [143], thus suggesting pivotal Ca2+-induced modulation of the choroid plexus-mediated CSF secretion machinery in health and disease.

Fig. 6. TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ influx activates NKCC1 and leads to CSF hypersecretion. Polarized localization of NKCC1 and TRPV4 in the luminal membrane of the choroid plexus with tight junctions marked with red bars. TRPV4 activation leads to Ca2+ entry, which activates the WNK/SPAK signaling pathway, terminating in phosphorylation and activation of NKCC1. P indicates phosphorylation of NKCC1. TRPV4; transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel, NKCC1; Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter 1, SPAK; SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase, WNK; with no lysine (WNK). The dashed arrow through NKCC1, terminating in a water droplet, indicates the cotransporter-mediated water transport via NKCC1.

5. Conclusion

The choroid plexus epithelium has been known for its core feature of CSF secretion for a century and for its contribution to controlling of the CSF K+ concentration for half a century. Nevertheless, precise and quantitative assignment of the different choroid plexus transport mechanisms to both of these pivotal physiological processes is, to some extent, still lacking, as highlighted in this review. With a range of brain pathologies associated with excess brain fluid accumulation and/or elevated [K+] in the brain extracellular fluid, both of which could be potentially fatal for the patient if left untreated, the need to understand these processes surfaces. With a future map of choroid plexus transport mechanisms involved in CSF secretion, and their regulatory properties, one may envision obtaining rational pharmacological targets towards limitation of CSF accumulation and thus reduction in ICP in patients with hydrocephalus and other pathologies involving disturbed brain fluid homeostasis. Diamox® is one of the few pharmacological options occasionally employed towards elevated ICP [144]. Its active ingredient is acetazolamide, an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase, of which 15 isoforms are expressed throughout the body [145], and several in the choroid plexus [96]. Acetazolamide has been demonstrated to reduce the rate of CSF secretion in rats by a mechanism within the choroid plexus itself, rather than by its effect on the systemic carbonic anhydrases, and to lower the ICP in the process [96]. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of acetazolamide to lower elevated ICP in patients have been questioned [146,147], in part due to its many systemic side effects [148] and thus poor patient compliance. Specific and efficient pharmacological approaches, based on the transport machinery of the choroid plexus, are thus needed to provide the medical community with alternative treatment strategies of some forms of hydrocephalus. It is our hope that this knowledge gap will be closed with ongoing and future research into this fascinating brain structure to ensure future pharmaceutical therapies towards these pathologies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

NM and TLTB performed the literature search and design the order of the review section. NM wrote the original draft and revised the figures, TLTB revised the manuscript and created Figs. 1,2,5,6, and graphical abstract.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was received from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Tandem grant number NNF17OC0024718 to NM), the Lundbeck Foundation (Grant Number R276-2018-403 and R313-2019-735 to NM and R303-2018-3005 to TLTB), Thorberg's Foundation (to NM), Independent Research Fund Denmark (Sapere Aude grant, to NM), the Carlsberg Foundation (to NM), Sofus Friis scholarship (to NM).

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Data availability

References