BEYOND REASON

어떤 사람에게는 좋은 음식이 어떤 사람에게는 독이 된다.

밀가루(글루텐) 음식을 끊고 자폐증, 알츠하이머, 정신질환이 완치되는 사례가 너무도 많다.

심지어 말초신경병증, gluten ataxia, 신경질환까지!!

- 탐구과제!!

클릭클릭(gluten sensitivity : from gut to brain)

켈리의 사례

- 켈리는 14살때 뇌기능장애 증상을 보이기 시작함. 짜증이 늘고 매일 두통과 집중력 장애가 발생. 4개월만에 두통은 격렬해지고 수면장애, 행동변화, 이유없이 울기, 무기력, 우울증. 정신과 의사에게 찾아가 베조디아제핀(항정신병약물)을 처방받음.

- 하지만 증상은 심해지면서 TV속 사람들이 자기를 겁주려고 TV밖으로 나온다고 믿음. 환각, 환청을 경험하기 시작함. 체중감소, 복부팽창, 심한 변비. 결국 정신과 병동에 입원함.

- 각종 검사에서 정상. 심지어 글리아딘 항체검사도 수치가 높지 않음.

- 아쉽게도 켈리가 입원한 정신병원에서는 글리아딘 항체만 검사함. 그래서 의사들은 켈리에게 밀(글루텐) 과민성이 있다고 생각하지 못함.

- 의사는 켈리가 희귀성 자가면역 뇌염이라고 진단해고 스테로이드를 처방하고 집으로 돌려보냄. 스테로이드가 염증을 감소시켜 일시적으로 일부 증세가 호전되는 듯 했으나 정신병 증상은 계속됨.

- 몇개월 후 켈리는 파스타를 먹고 갑작스런 울음, 혼란, 보행실조, 심한 불안, 편집증적 정신착란 증상이 보임. 다시 정신병동으로 보내졌고 이후 수개월동안 수차례 입원치료함.

- 1년 후 정신병 증상이 계속된 켈리는 체중이 15% 감소하여 영양사와 식이요법을 상담함.

- 영양사는 켈리의 소화장애를 고려하여 글루텐 프리식단을 처방함.

'놀랍게도 1주일만에 켈리의 모든 증상은 극적으로 개선됨'

- 켈리는 수차례 셀리악병 검사(글루텐민감성 장질환)를 받았지만 결과는 언제나 정상이었음.

- 셀리는 셀리악병이 아닌 글루텐 과민성이 뇌에 중대한 영향을 미치는 전형적인 사례임.

- 켈리는 글루텐 프리 식단을 처방한 영양사를 만나지 못했다면 평생 정신과 병동에서 보낼뻔 함.

정리

글루텐과 관련된 신경증-정신병 증상은 글루텐의 불완전한 분해로 형성된 오피오이드 펩티드를 과도하게 흡수한 결과로 추정됨. 장누수 증후군은 이런 펩티드가 장점막을 거쳐 혈류로 침투하여 혈액뇌장벽을 통과, 신경계내에 염증을 일으킴.

Nutrients

. 2015 Jul 8;7(7):5532–5539. doi: 10.3390/nu7075235

Gluten Psychosis: Confirmation of a New Clinical Entity

Elena Lionetti 1,*, Salvatore Leonardi 1, Chiara Franzonello 1, Margherita Mancardi 2, Martino Ruggieri 1, Carlo Catassi 3,4

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC4517012 PMID: 26184290

Abstract

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a syndrome diagnosed in patients with symptoms that respond to removal of gluten from the diet, after celiac disease and wheat allergy have been excluded. NCGS has been related to neuro-psychiatric disorders, such as autism, schizophrenia and depression. A singular report of NCGS presenting with hallucinations has been described in an adult patient. We report a pediatric case of a psychotic disorder clearly related to NCGS and investigate the causes by a review of literature. The pathogenesis of neuro-psychiatric manifestations of NCGS is unclear. It has been hypothesized that: (a) a “leaky gut” allows some gluten peptides to cross the intestinal membrane and the blood brain barrier, affecting the endogenous opiate system and neurotransmission; or (b) gluten peptides may set up an innate immune response in the brain similar to that described in the gut mucosa, causing exposure from neuronal cells of a transglutaminase primarily expressed in the brain. The present case-report confirms that psychosis may be a manifestation of NCGS, and may also involve children; the diagnosis is difficult with many cases remaining undiagnosed. Well-designed prospective studies are needed to establish the real role of gluten as a triggering factor in neuro-psychiatric disorders.

요약

Non-celiac 글루텐 과민증(NCGS)은

셀리악 질병과 밀 알레르기가 배제된 후,

식단에서 글루텐을 제거하는 것이 증상 완화에 도움이 되는 것으로 진단된 증후군입니다.

NCGS는

자폐증, 정신분열증, 우울증과 같은

신경정신과적 장애와 관련이 있습니다.

성인 환자에서 환각을 보이는

NCGS에 대한 보고가 한 건 있었습니다.

우리는 NCGS와 명확하게 관련된

정신병적 장애의 소아 사례를 보고하고

문헌 검토를 통해 원인을 조사합니다.

신경정신과적 증상이 나타나는 NCGS의 병인은 아직 명확하지 않습니다.

다음과 같은 가설이 제시되고 있습니다:

(a) “새는 장 증후군”으로 인해

일부 글루텐 펩타이드가 장막과 혈액 뇌 장벽을 통과하여

내인성 아편계와 신경 전달에 영향을 미치거나,

(b) 글루텐 펩타이드가

장 점막에서 설명된 것과 유사한 선천성 면역 반응을 뇌에서 일으켜,

주로 뇌에서 발현되는 트랜스글루타민아제의 신경세포 노출을 유발할 수 있습니다.

이 사례 보고서는

정신병이 NCGS의 증상일 수 있으며,

어린이에게도 영향을 미칠 수 있음을 확인해 줍니다.

많은 사례가 진단되지 않은 채 남아 있기 때문에 진단이 어렵습니다.

글루텐이 신경정신과적 장애의 유발 요인으로서

실제 어떤 역할을 하는지 확인하기 위해서는

잘 설계된 전향적 연구가 필요합니다.

Keywords: gluten, hallucinations, non celiac gluten sensitivity, psycosis

1. Introduction

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a syndrome diagnosed in patients with symptoms that respond to removal of gluten from the diet, after CD and wheat allergy have been excluded [1,2]. The description of this condition is mostly restricted to adults, including a large number of patients previously labeled with “irritable bowel syndrome” or “psychosomatic disorder” [1].

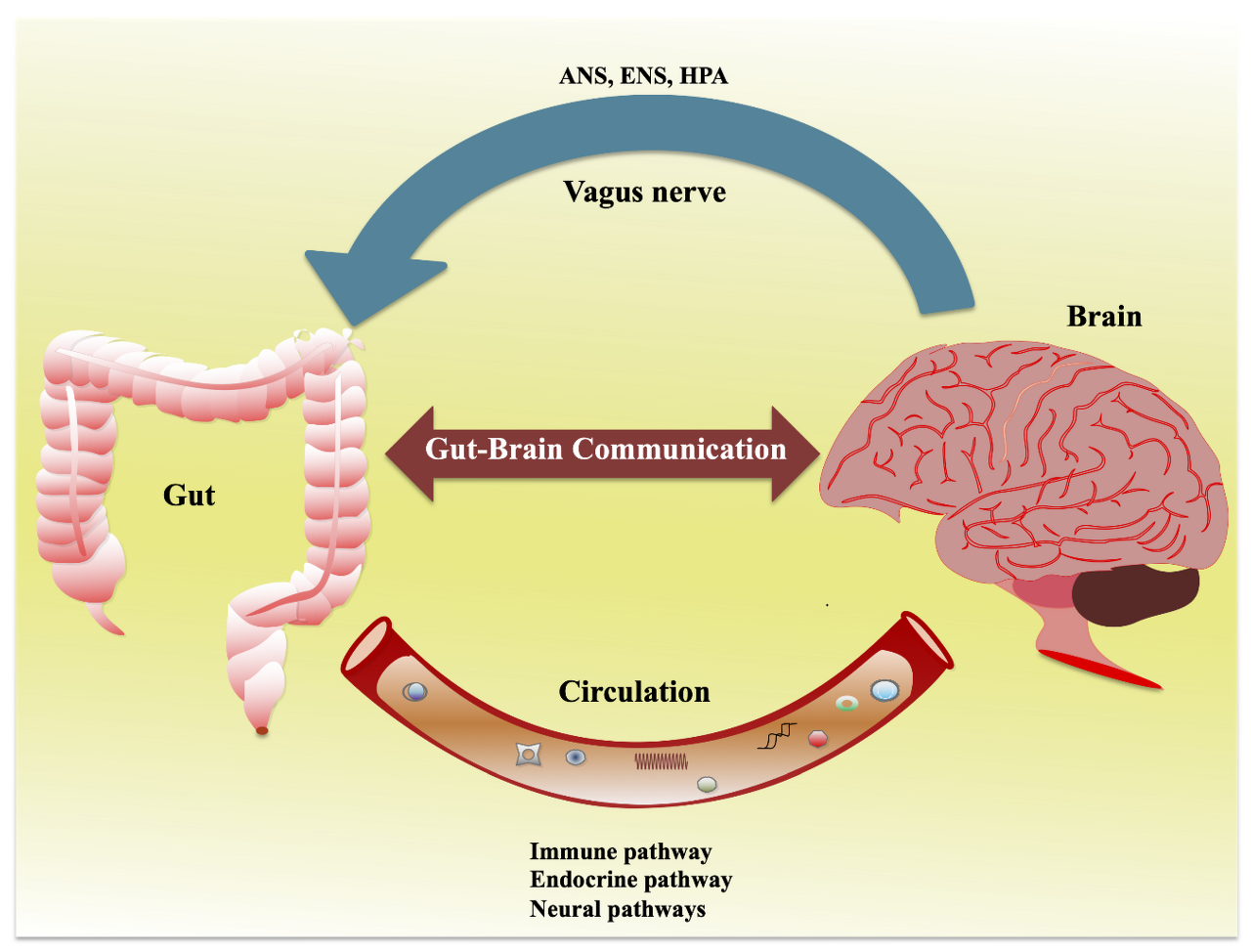

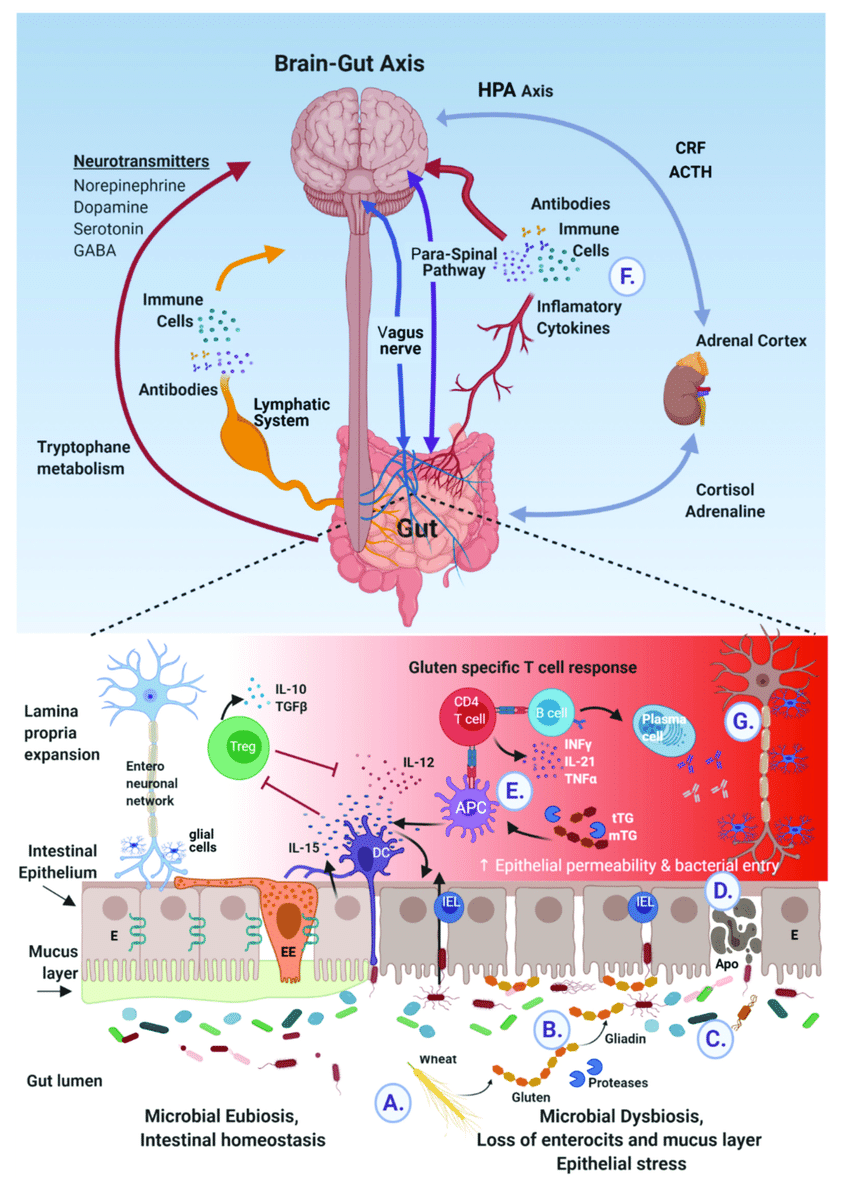

The “classical” presentation of NCGS is, indeed, a combination of gastro-intestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, bowel habit abnormalities (either diarrhea or constipation), and systemic manifestations including disorders of the neuropsychiatric area such as “foggy mind”, depression, headache, fatigue, and leg or arm numbness [1,2,3]. In recent studies, NCGS has been related to the appearance of neuro-psychiatric disorders, such as autism, schizophrenia and depression [2,4]. The proposed mechanism is a CD-unrelated, primary alteration of the small intestinal barrier (leaky gut) leading to abnormal absorption of gluten peptides that can eventually reach the central nervous system stimulating the brain opioid receptors and/or causing neuro-inflammation. A singular report of NCGS presenting with hallucinations has also been described in an adult patient showing an indisputable correlation between gluten and psychotic symptoms [5].

Here we report a pediatric case of a psychotic disorder clearly related to NCGS.

1. 소개

비셀리악 글루텐 과민증(NCGS)은

CD와 밀 알레르기가 배제된 후,

식단에서 글루텐을 제거하는 것에 반응하는 증상을 보이는 환자들에게서 진단되는 증후군입니다 [1,2].

이 상태에 대한 설명은 주로 성인에 국한되어 있으며,

이전에는 “과민성 대장 증후군” 또는 “

심인성 장애”로 분류되었던 많은 환자들을 포함합니다 [1].

NCGS의 “고전적” 표현은

실제로 복통, 복부팽만감, 배변 습관의 이상(설사 또는 변비), 그리고

“정신이 멍한 상태”, 우울증, 두통, 피로, 다리 또는 팔의 저림과 같은

신경정신과적 장애를 포함한 전신 증상 등 위장 증상을 포함하는 조합입니다 [1,2,3].

최근 연구에 따르면,

NCGS는

자폐증, 정신분열증, 우울증과 같은

신경정신과적 장애의 출현과 관련이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다 [2,4].

제안된 메커니즘은

CD(셀리악병)와 무관한 소장 장벽의 1차적 변화(새는 장 증후군)로,

글루텐 펩타이드의 비정상적인 흡수를 초래하여

결국 중추신경계를 자극하는 뇌 오피오이드 수용체를 자극하거나

신경염을 유발할 수 있습니다.

글루텐과 정신병적 증상 사이에 명백한 상관관계가 있는 것으로 보이는

성인 환자에 대한 NCGS의 단일 보고서가 발표된 바 있습니다 [5].

여기에서는

NCGS와 명확하게 관련된

정신병적 장애의 소아 사례를 보고합니다.

2. Case Report

A 14-year-old girl came to our outpatient clinic for psychotic symptoms that were apparently associated with gluten consumption.

The pediatric ethical committee of the Azienda Universitaria Ospedaliera Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele di Catania approved the access to the patient records. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child.

She was first-born by normal delivery of non-consanguineous parents. Her childhood development and growth were normal. The mother was affected by autoimmune thyroiditis. She had been otherwise well until approximately two years before. In May 2012, after a febrile episode, she became increasingly irritable and reported daily headache and concentration difficulties. One month after, her symptoms worsened presenting with severe headache, sleep problems, and behavior alterations, with several unmotivated crying spells and apathy. Her school performance deteriorated, as reported by her teachers. The mother noted severe halitosis, never suffered before. The patient was referred to a local neuropsychiatric outpatient clinic, where a conversion somatic disorder was diagnosed and a benzodiazepine treatment (i.e., bromazepam) was started. In June 2012, during the final school examinations, psychiatric symptoms, occurring sporadically in the previous two months, worsened. Indeed, she began to have complex hallucinations. The types of these hallucinations varied and were reported as indistinguishable from reality. The hallucinations involved vivid scenes either with family members (she heard her sister and her boyfriend having bad discussions) or without (she saw people coming off the television to follow and scare her), and hypnagogic hallucinations when she relaxed on her bed. She also presented weight loss (about 5% of her weight) and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal distension and severe constipation.

She was admitted to a psychiatric ward. Detailed physical and neurological examinations, as well as routine blood tests were normal. In order to exclude an organic neuropsychiatric cause of psychosis, the following tests were done: rheumatoid factor, streptococcal antibody tests, autoimmunity profile (including anti-nuclear, anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-Saccharomyces, anti-phospholipid, anti-mitochondrial, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, anti-transglutaminase IgA (tTG), anti-endomysium (EMA), and anti-gliadin IgA (AGA) antibodies), and screening for infectious and metabolic diseases, but they resulted all within the normal range. The only abnormal parameters were anti-thyroglobulin and thyroperoxidase antibodies (103 IU/mL, and 110 IU/mL; v.n. 0–40 IU/mL). A computed tomography scan of the brain and a blood pressure holter were also performed and resulted normal. Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed mild nonspecific abnormalities and slow-wave activity. Due to the abnormal autoimmune parameters and the recurrence of psychotic symptoms, autoimmune encephalitis was suspected, and steroid treatment was initiated. The steroid led to partial clinical improvement, with persistence of negative symptoms, such as emotional apathy, poverty of speech, social withdrawal and self-neglect. Her mother recalled that she did not return a “normal girl”. In September 2012, shortly after eating pasta, she presented crying spells, relevant confusion, ataxia, severe anxiety and paranoid delirium. Then she was again referred to the psychiatric unit. A relapse of autoimmune encephalitis was suspected and treatment with endovenous steroid and immunoglobulins was started. During the following months, several hospitalizations were done, for recurrence of psychotic symptoms. Cerebral and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging, lumbar puncture, and fundus oculi examination did not show any pathological signs. Several EEG were performed confirming bilateral slow activity. The laboratory tests showed only mild microcytic anemia with reduced levels of ferritin and a slight increase in fecal calprotectin values (350 mg/dL, normal range: 0–50 mg/dL).

In September 2013, she presented with severe abdominal pain, associated with asthenia, slowed speech, depression, distorted and paranoid thinking and suicidal ideation up to a state of pre-coma. The clinical suspicion was moving towards a fluctuating psychotic disorder. Treatment with a second-generation anti-psychotic (i.e., olanzapine) was started, but psychotic symptoms persisted. In November 2013, due to gastro-intestinal symptoms and further weight loss (about 15% of her weight in the last year), a nutritionist was consulted, and a gluten-free diet (GFD) was recommended for symptomatic treatment of the intestinal complaints; unexpectedly, within a week of gluten-free diet, the symptoms (both gastro-intestinal and psychiatric) dramatically improved, and the GFD was continued for four months. Despite her efforts, she occasionally experienced inadvertent gluten exposures, which triggered the recurrence of her psychotic symptoms within about four hours. Symptoms took two to three days to subside again. Then, in April 2014 (two years after the onset of symptoms), she was admitted to our pediatric gastroenterology outpatient for suspected NCGS. Previous examinations excluded a diagnosis of CD because serology for CD was negative (i.e., EMA, and tTG).

A wheat allergy was excluded due to negativity of specific IgE to wheat, prick test, prick by prick and patch test for wheat resulted negative. Therefore, we decided to perform a double-blind challenge test with wheat flour and rice flour (one pill containing 4 g of wheat flour or rice flour for the first day, following two pills in the second day and 4 pills from the third day to 15 days, with seven days of wash-out between the two challenges). During the administration of rice flour, symptoms were absent. During the second day of wheat flour intake, the girl presented headache, halitosis, abdominal distension, mood disorders, fatigue, and poor concentration, and three episodes of severe hallucinations. After the challenge, she tested negative for: (1) CD serology (EMA and tTG); (2) food specific IgE; (3) skin prick test to wheat (extract and fresh food); (4) atopy patch test to wheat; and (5) duodenal biopsy. Only serum anti-native gliadine antibodies of IgG class and stool calprotectin were elevated.

Due to parental choice, the girl did not continue assuming gluten and she started a gluten-free diet with a complete regression of all symptoms within a week. The adherence to the GFD was evaluated by a validated questionnaire [6]. One month after AGA IgG and calprotectin resulted negative, as well as the EEG, and ferritin levels improved. She returned to the same neuro-psychiatric specialists that now reported a “normal behavior” and progressively stopped the olanzapine therapy without any problem. Her mother finally recalled that she was returned a “normal girl”. Nine months after definitely starting the GFD, she is still symptoms-free.

2. 사례 보고서

14세 소녀가

글루텐 섭취와 관련된 정신병적 증상을 호소하며

저희 외래 진료소에 찾아왔습니다.

카타니아의 폴리클리니코 비토리오 에마누엘레 대학병원의 소아 윤리위원회는

환자 기록에 대한 접근을 승인했습니다.

부모로부터 서면 동의서를 받았습니다.

이 소녀는 친척이 아닌 부모로부터 정상적으로 태어난 첫째 딸입니다.

그녀의 유년기 발달과 성장 과정은 정상적이었습니다.

어머니는 자가면역성 갑상선염에 걸렸습니다.

그녀는 약 2년 전까지는 건강했습니다.

2012년 5월,

발열 증세가 나타난 후,

그녀는 점점 짜증을 내기 시작했고,

매일 두통과 집중력 저하를 호소했습니다.

한 달 후,

그녀의 증상은

심한 두통, 수면 장애, 행동 변화,

몇 번의 이유 없는 울음, 무관심으로 악화되었습니다.

그녀의 학교 성적은 교사들에 의해 악화되었다고 보고되었습니다. 어머니는 딸이 전에는 경험하지 못했던 심한 구취를 호소했다고 합니다.

환자는 지역 신경정신과 외래 진료소로 의뢰되었고,

그곳에서 전환 신체 장애 conversion somatic disorder 진단을 받고

벤조디아제핀 치료(브로마제팜)를 시작했습니다.

2012년 6월,

최종 학교 시험 기간 동안

정신과적 증상이 악화되었습니다.

실제로,

그녀는

복잡한 환각을 경험하기 시작했습니다.

환각의 유형은 다양했으며

현실과 구분할 수 없는 것으로 보고되었습니다.

환각은

가족 구성원(그녀는 언니와 남자 친구가 심하게 다투는 소리를 들었다)과 관련된

생생한 장면이거나(그녀는 사람들이 그녀를 따라오기 위해 텔레비전 밖으로 나오는 것을 보았다),

침대에서 휴식을 취할 때의 최면 상태의 환각이었습니다.

그녀는 또한

체중 감소(체중의 약 5%)와

복부 팽창, 심한 변비 같은 위장 증상도 호소했습니다.

그녀는 정신과 병동에 입원했습니다.

상세한 신체 및 신경학적 검사,

그리고 일상적인 혈액 검사는 정상으로 나타났습니다.

정신증의 유기적 신경정신학적 원인을 배제하기 위해,

류마티스 인자,

연쇄상구균 항체 검사,

자가면역 프로파일(항핵, 항-이중가닥 DNA, 항-호중구 세포질, 항-사카로마이세스, 항- 인지질, 항-미토콘드리아, 항-SSA/Ro, 항-SSB/La, 항-트랜스글루타미나제 IgA(tTG), 항-내장근(EMA), 항-글리아딘 IgA(AGA) 항체),

그리고 감염성 및 대사성 질환에 대한 선별 검사,

그러나 모두 정상 범위 내에 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.

including anti-nuclear, anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-Saccharomyces, anti-phospholipid, anti-mitochondrial, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, anti-transglutaminase IgA (tTG), anti-endomysium (EMA), and anti-gliadin IgA (AGA) antibodies), and screening for infectious and metabolic diseases

유일하게 비정상적인 수치는

항티로글로불린과 티로퍼옥시다아제 항체(103 IU/mL, 110 IU/mL; 정상 범위 0-40 IU/mL)였습니다.

뇌의 컴퓨터 단층 촬영과 혈압 홀터 검사도 실시되었지만,

결과는 정상으로 나왔습니다.

뇌파 검사(EEG)에서는

경미한 비특이적 이상과 느린 파동 활동이 나타났습니다.

비정상적인 자가면역 매개변수와 정신병적 증상의 재발로 인해

자가면역성 뇌염이 의심되어

스테로이드 치료를 시작했습니다.

스테로이드 치료로 인해

부분적인 임상적 개선이 있었지만,

정서적 무관심, 언어의 빈곤, 사회적 고립, 자기 방치와 같은

부정적 증상이 지속되었습니다.

그녀의 어머니는 그녀가 “평범한 소녀”가 아니었다고 회상했습니다.

2012년 9월,

파스타를 먹은 직후,

그녀는 울음 발작, 관련 혼란, 운동 실조, 심각한 불안, 편집증적 망상증상을 보였습니다.

그리고 다시 정신과로 의뢰되었습니다.

자가면역성 뇌염의 재발이 의심되어,

정맥 내 스테로이드와 면역글로불린 치료를 시작했습니다.

그 후 몇 달 동안

정신병적 증상이 재발하면서

여러 차례 입원했습니다.

뇌와 척수 자기공명영상,

요추천자,

안저 검사에서 병리학적 징후는 발견되지 않았습니다.

여러 차례 뇌파 검사를 실시하여

양측성 느린 활동을 확인했습니다.

실험실 검사 결과,

페리틴 수치가 감소하고

대변 내 칼프로텍틴 수치가 약간 증가한

경미한 소세포성 빈혈만 나타났습니다(350mg/dL, 정상 범위: 0-50mg/dL).

2013년 9월,

그녀는 무력증과 관련된 심한 복통, 느린 말, 우울증,

왜곡되고 편집증적인 사고,

혼수상태에 이를 정도의 자살 충동 등을 보였습니다.

임상적 의심은

변동성 정신병 fluctuating psychotic disorder 으로 발전하는 쪽으로

기울었습니다.

2세대 항정신병제(즉, 올란자핀)를 사용한 치료가 시작되었지만,

정신병적 증상은 지속되었습니다.

2013년 11월,

위장 증상과 체중 감소(작년 대비 체중의 약 15%)로 인해

영양사와 상담을 했고,

장 질환의 증상 치료를 위해 글루텐 프리 다이어트(GFD)를 권장받았습니다.

예상치 못하게

글루텐 프리 다이어트를 시작한 지 일주일 만에

위장 및 정신과적 증상이 극적으로 개선되었고,

GFD는 4개월 동안 지속되었습니다.

노력에도 불구하고,

그녀는 때때로 우발적인 글루텐 노출을 경험했고,

이로 인해 약 4시간 내에 정신병적 증상이 재발했습니다.

증상이

다시 가라앉기까지

2~3일이 걸렸습니다.

그리고

2014년 4월(증상 발현 후 2년),

그녀는 NCGS 의심으로 소아 위장병 외래에 입원했습니다.

이전 검사에서는 CD 진단을 배제했습니다.

CD에 대한

혈청학 검사(EMA, tTG 등)에서

음성이 나왔기 때문입니다.

밀 알레르기는

밀에 대한 특이 IgE가 음성으로 나왔고,

밀에 대한 찌르기 검사,

찌르기 대 찌르기 검사,

패치 검사에서 음성이 나왔기 때문에 배제되었습니다.

따라서 밀가루와 쌀가루를 이용한 이중 맹검 시험을 실시하기로 했습니다(첫날에는 밀가루 또는 쌀가루 4g을 함유한 알약 1개, 둘째 날에는 2개, 셋째 날부터는 4개씩 15일까지, 두 번의 시험 사이에 7일의 휴약 기간을 두었습니다). 쌀가루를 섭취한 첫날에는 증상이 나타나지 않았습니다. 밀가루를 섭취한 둘째 날, 소녀는 두통, 구취, 복부 팽만감, 기분 장애, 피로, 집중력 저하, 그리고 세 번의 심각한 환각 증상을 보였습니다. 이 후, 그녀는 다음 항목에 대해 음성 판정을 받았습니다. (1) CD 혈청학(EMA 및 tTG); (2) 식품 특이성 IgE; (3) 밀(추출물 및 신선 식품)에 대한 피부 단자 검사; (4) 밀에 대한 아토피 패치 검사; (5) 십이지장 생검. IgG 클래스의 혈청 항-글리아딘 항체와 대변 칼프로텍틴만이 상승했습니다.

A wheat allergy was excluded due to negativity of specific IgE to wheat, prick test, prick by prick and patch test for wheat resulted negative. Therefore, we decided to perform a double-blind challenge test with wheat flour and rice flour (one pill containing 4 g of wheat flour or rice flour for the first day, following two pills in the second day and 4 pills from the third day to 15 days, with seven days of wash-out between the two challenges). During the administration of rice flour, symptoms were absent. During the second day of wheat flour intake, the girl presented headache, halitosis, abdominal distension, mood disorders, fatigue, and poor concentration, and three episodes of severe hallucinations. After the challenge, she tested negative for: (1) CD serology (EMA and tTG); (2) food specific IgE; (3) skin prick test to wheat (extract and fresh food); (4) atopy patch test to wheat; and (5) duodenal biopsy. Only serum anti-native gliadine antibodies of IgG class and stool calprotectin were elevated.

부모의 선택에 따라,

그 소녀는 글루텐을 계속 섭취하지 않았고,

일주일 안에 모든 증상이 완전히 사라지는 글루텐 프리 식단을 시작했습니다.

GFD 준수 여부는 검증된 설문지를 통해 평가되었습니다 [6]. AGA IgG와 칼프로텍틴 검사에서 음성 결과가 나온 지 한 달 후, 뇌파 검사 결과와 페리틴 수치도 개선되었습니다. 그녀는 같은 신경정신과 전문의에게 다시 진료를 받았고, 그 전문의는 “정상적인 행동”을 보고했고, 아무런 문제 없이 올란자핀 치료를 점진적으로 중단했습니다.

그녀의 어머니는 마침내 그녀가 “정상적인 소녀”로 돌아왔다는 것을 기억해 냈습니다.

GFD를 확실히 시작한 지 9개월이 지난 지금도 그녀는 아무런 증상도 보이지 않습니다.

3. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a pre-pubertal child presenting with a severe psychotic manifestation that was clearly related to the ingestion of gluten-containing food and showing complete resolution of symptoms after starting treatment with the gluten-free diet.

Until a few years ago, the spectrum of gluten-related disorders included only CD and wheat allergy, therefore our patient would be turned back home as a “psychotic patient” and receive lifelong treatment with anti-psychotic drugs. Recent data, however, suggested the existence of another form of gluten intolerance, known as NCGS [2,4,7]. NCGS is a condition in which symptoms are triggered by gluten ingestion, in the absence of celiac-specific antibodies and of classical celiac villous atrophy, with variable HLA status and variable presence of first generation AGA. Symptoms usually occur soon after gluten ingestion, disappear with gluten withdrawal and relapse following gluten challenge, within hours or few days. No specific blood test is available for diagnosing NCGS [2].

In our case report, the correlation of psychotic symptoms with gluten ingestion and the following diagnosis of NGCS were well demonstrated; the girl was, indeed, not affected by CD, because she showed neither the typical CD-related autoantibodies (anti-tTG and EMA) nor the signs of intestinal damage at the small intestinal biopsy. Features of an allergic reaction to gluten were lacking as well, as shown by the absence of IgE or T-cell-mediated abnormalities of immune response to wheat proteins. The double-blind gluten challenge, currently considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of NCGS, clearly showed that the elimination and reintroduction of gluten was followed by the disappearance and reappearance of symptoms.

Interestingly, a similar case-report of a 23-years-old female with auditory and visual hallucinations that resolved with gluten elimination has been recently reported [5].

3. 토론

저희가 아는 한, 이 사례는

글루텐 함유 식품 섭취와 명확하게 연관되어 있는

심각한 정신병적 증상을 보이는 사춘기 이전 아동에 대한 최초의 설명이며,

글루텐 프리 식단으로 치료를 시작한 후 증상이 완전히 해결된 사례입니다.

몇 년 전까지만 해도

글루텐 관련 질환의 스펙트럼은

CD와 밀 알레르기만 포함했기 때문에,

우리 환자들은 “정신병 환자”로 분류되어 항정신병 약물로 평생 치료를 받아야 했습니다.

그러나

최근의 데이터에 따르면

NCGS로 알려진

또 다른 형태의 글루텐 불내성이 존재한다고 합니다 [2,4,7].

NCGS는

celiac 특이 항체와 전형적인 체강 융모성 위축증이 없는 상태에서

글루텐 섭취로 인해 증상이 유발되는 질환으로,

HLA 상태와 1세대 AGA의 존재 여부가 다양합니다.

증상은 보통 글루텐 섭취 직후에 나타나며,

글루텐 섭취 중단으로 사라졌다가 글루텐 섭취 후 재발하며,

몇 시간 또는 며칠 내에 사라집니다.

NCGS 진단을 위한

특정 혈액 검사는 없습니다 [2].

이 사례 보고서에서

정신병적 증상과 글루텐 섭취의 상관관계,

그리고 NGCS 진단이 잘 입증되었습니다.

이 소녀는

소장 생검에서 CD와 관련된 전형적인 자가 항체(항-tTG 및 EMA)나

장 손상 징후가 나타나지 않았기 때문에

실제로 CD의 영향을 받지 않았습니다.

밀 단백질에 대한 IgE 또는 T세포 매개 면역 반응의 이상이 없었기 때문에

글루텐 알레르기 반응의 특징도 결여되어 있었습니다.

현재 NCGS 진단의 표준으로 간주되는 이중맹검 글루텐 챌린지는

글루텐을 제거하고 다시 섭취했을 때

증상이 사라졌다가 다시 나타났다는 것을 분명히 보여주었습니다.

흥미롭게도,

최근에 글루텐 섭취를 중단함으로써

청각과 시각적 환각이 사라진 23세 여성의 유사한 사례 보고가 있었습니다 [5].

부모의 선택에 따라, 그

소녀는 글루텐을 계속 섭취하지 않았고,

일주일 안에 모든 증상이 완전히 사라지는 글루텐 프리 식단을 시작했습니다.

GFD 준수 여부는 검증된 설문지를 통해 평가되었습니다 [6].

AGA IgG와 칼프로텍틴 검사에서

음성 결과가 나온 지 한 달 후,

뇌파 검사 결과와 페리틴 수치도 개선되었습니다. 그

녀는 같은 신경정신과 전문의에게 다시 진료를 받았고,

그 전문의는 “정상적인 행동”을 보고했고,

아무런 문제 없이 올란자핀 치료를 점진적으로 중단했습니다.

그녀의 어머니는 마침내 그녀가 “정상적인 소녀”로 돌아왔다는 것을 기억해 냈습니다.

GFD를 확실히 시작한 지 9개월이 지난 지금도 그녀는 아무런 증상도 보이지 않습니다.

The present case-report confirms that: (a) psychotic disorders may be a manifestation of NCGS; (b) neuro-psychiatric symptoms may involve also children with NCGS; and (c) the diagnosis is difficult and many cases may remain undiagnosed.

The possible causes of psychosis in children and young people are not well understood. It is thought to be the result of a complex interaction of genetic, biological, psychological and social factors. However, we still know relatively little about which specific genes or environmental factors are involved and how these factors interact and actually cause psychotic symptoms [8]. Several studies suggested a relationship between gluten and psychosis [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] or other neuro-psychiatric disorders [28,29,30,31]; however, it remains a highly debated and controversial topic that requires well-designed prospective studies to establish the real role of gluten as a triggering factor in these diseases [2,27].

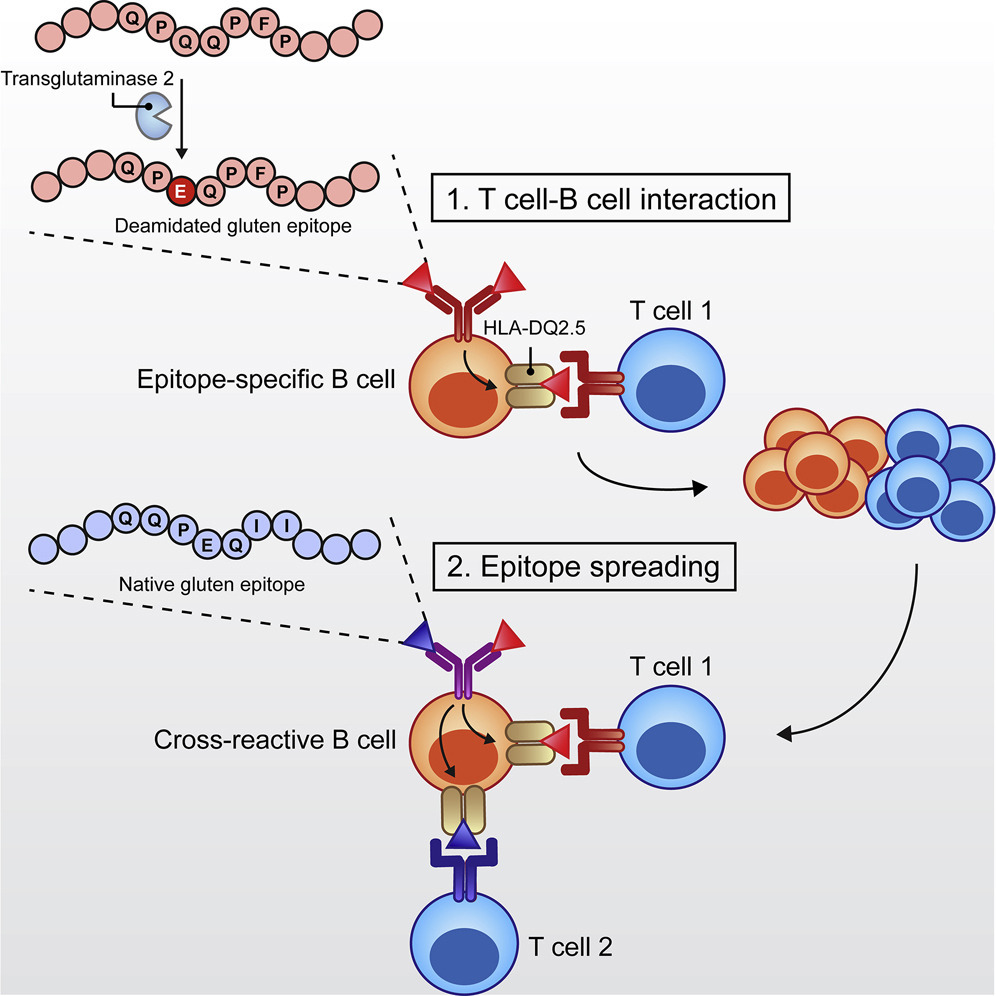

On the other hand, the pathogenesis of neuro-psychiatric manifestations of NCGS is an intriguing and still poorly understood issue. It has been hypothesized that some neuro-psychiatric symptoms related to gluten may be the consequence of the excessive absorption of peptides with opioid activity that formed from incomplete breakdown of gluten. Increased intestinal permeability, also referred to as “leaky gut syndrome”, may allows these peptides to cross the intestinal membrane, enter the bloodstream, and cross the blood brain barrier, affecting the endogenous opiate system and neurotransmission within the nervous system [2,32]. Interestingly, in our case, we observed an elevation of fecal calprotectin that resolved during gluten-free diet, suggesting that a certain degree of gut inflammation may be found in NCGS. The role of stool calprotectin as a biomarker of NCGS requires further evaluation.

이 사례 보고서는

(a) 정신병적 장애가 NCGS의 증상일 수 있다는 점,

(b) 신경정신과적 증상이 NCGS 아동에게도 나타날 수 있다는 점,

(c) 진단이 어렵고 많은 사례가 진단되지 않은 채 남아 있을 수 있다는 점을 확인해 줍니다.

어린이와 청소년의 정신병의 가능한 원인은 잘 알려져 있지 않습니다.

유전적, 생물학적, 심리적, 사회적 요인의 복잡한 상호 작용의 결과로 발생하는 것으로 여겨집니다.

그러나

어떤 특정 유전자 또는 환경적 요인이 관련되어 있는지,

그리고 이러한 요인들이 어떻게 상호 작용하여

실제로 정신병적 증상을 유발하는지에 대해서는

아직 상대적으로 잘 알려져 있지 않습니다 [8].

여러 연구에서

글루텐과 정신병[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] 또는

기타 신경정신과적 장애[28,29,30,31] 사이의 연관성을 시사했습니다.

그러나 글루텐이 이러한 질병의 유발 인자로서 실제 어떤 역할을 하는지 확인하기 위해서는 잘 설계된 전향적 연구가 필요한 매우 논쟁적이고 논란이 많은 주제입니다 [2,27].

반면, NCGS의 신경정신학적 증상의 병인은 흥미롭지만 아직까지 제대로 이해되지 않은 문제입니다.

글루텐과 관련된 일부 신경정신학적 증상은

글루텐의 불완전한 분해로 인해 형성된

오피오이드 활성을 가진 펩타이드의 과도한 흡수의 결과일 수 있다는 가설이 제기되었습니다.

장 투과성 증가, 일명 “새는 장 증후군”은

이러한 펩타이드가 장막을 통과하여

혈류로 들어가서 혈액 뇌 장벽을 통과하게 함으로써

내인성 아편계와 신경계 내의 신경 전달에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다 [2,32].

흥미롭게도, 우리의 경우, 글루텐 프리 식단을 통해 대변 내 칼프로텍틴 수치가 상승하는 현상이 관찰되었는데, 이는 NCGS에서 어느 정도의 장 염증이 발견될 수 있음을 시사합니다. 대변 칼프로텍틴이 NCGS의 바이오마커로서의 역할은 추가적인 평가가 필요합니다.

Recently, a higher prevalence of antibodies directed toward tTG6 (a transglutaminase primarily expressed in the brain) has been observed in adult patients affected by schizophrenia [26]; this finding suggests that these autoantibodies could have a role in the pathogenesis of the neuro-psychiatric manifestations seen in NCGS. It is possible that gluten peptides (either directly or through activation of macrophages/dendritic cells) may set up an innate immune response in the brain similar to that described in the gut mucosa, causing exposure of tTG6 from neuronal cells. Access of these gluten peptides and/or activated immune cells to the brain may be facilitated by a breach of the blood brain barrier [26]. Evidence from the literature supports the notion that a subgroup of psychotic patients shows increased expression of inflammatory markers including haptoglobin-2 chains α and β [33]. Zonulin is a tight junction modulator that is released by the small intestine mucosa upon gluten stimulation. Interestingly the zonulin receptor, identified as the precursor for haptoglobin-2, has been found in the human brain. Overexpression of zonulin (aka haptoglobin-2) could be involved in the blood brain barrier disruption similarly to the role that zonulin plays in increasing intestinal permeability. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that zonulin analogues can modulate the blood brain barrier by increasing its permability to high molecular weight markers and chemotherapeutic agents. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on early detection and intervention of psychotic symptoms in order to delay or possibly prevent the onset of psychosis and schizophrenia [8]. Children and young people with schizophrenia tend to have a shorter life expectancy than the general population, largely because of suicide, injury, or cardiovascular disease, the last partly related to chronic treatment with antipsychotic medication [34]. Moreover, psychotic disorders in children and young people (up to age 17 years) are the leading causes of disability, owing to disruption to social and cognitive development [8]. Shedding light on the possible role of gluten in this context may significantly change the life for a subset of these patients, as shown by the case described in this case-report.

최근에,

정신분열증에 걸린 성인 환자들에서

tTG6(주로 뇌에서 발현되는 트랜스글루타미나제)에 대한

항체의 높은 유병률이 관찰되었습니다 [26];

이 발견은

이러한 자가항체가 NCGS에서 나타나는 신경정신과적 증상의 병인에

중요한 역할을 할 수 있음을 시사합니다.

글루텐 펩티드(직접 또는 대식세포/수지상 세포의 활성화를 통해)가

장 점막에서 설명된 것과 유사한 선천성 면역 반응을 뇌에서 일으켜서

신경 세포에서 tTG6가 노출될 수 있습니다.

이러한 글루텐 펩타이드 및/또는 활성화된 면역세포가

뇌에 접근하는 것은 혈액 뇌 장벽의 파괴에 의해 촉진될 수 있습니다 [26].

문헌에 따르면,

정신병 환자 중 일부는

합토글로빈-2α 및 β 사슬을 포함한 염증성 표지자의 발현이 증가한다는 사실이 입증되었습니다 [33].

조눌린은

글루텐 자극에 의해 소장 점막에서 분비되는 밀착 접합 조절제입니다.

흥미롭게도,

합토글로빈-2의 전구체로 확인된 조눌린 수용체가 인간의 뇌에서 발견되었습니다.

조눌린(일명 합토글로빈-2)의 과다 발현은

장 투과성을 증가시키는 조눌린의 역할과 유사하게

혈액 뇌 장벽 파괴에 관여할 수 있습니다.

이 가설은 조눌린 유사체가

고분자량 표지자와 화학요법제에 대한 투과성을 증가시킴으로써

혈액 뇌 장벽을 조절할 수 있다는 관찰에 의해 뒷받침됩니다.

최근에는

정신분열증과 조현병의 발병을 지연시키거나 예방하기 위해

정신증상의 조기 발견과 개입에 대한 강조가 커지고 있습니다 [8].

조현병을 앓고 있는 어린이와 청소년은

일반 인구보다 자살, 부상, 심혈관 질환으로 인한 사망률이 더 높은 경향이 있는데,

이 중 심혈관 질환은 부분적으로 항정신병 약물의 만성적 투여와 관련이 있습니다 [34].

또한, 아동과 청소년(17세 이하)의 정신병적 장애는

사회적, 인지적 발달 장애로 인한 장애의 주요 원인입니다 [8].

이 사례 보고서에 설명된 사례에서 알 수 있듯이,

이러한 맥락에서 글루텐의 가능한 역할에 대한 이해는

이러한 환자들 중 일부의 삶을 크게 변화시킬 수 있습니다.

4. Conclusions

The present case report shows that psychosis may be a manifestation of NCGS, and may also involve children; the diagnosis is difficult with many cases remaining undiagnosed. The pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric manifestations of NCGS is an intriguing and still poorly understood issue. Well designed prospective studies are needed to establish the real role of gluten as a triggering factor in these diseases.

4. 결론

이 사례 보고서는 정신병이 NCGS의 증상일 수 있으며, 어린이에게도 나타날 수 있다는 것을 보여줍니다. 진단이 어려운 경우가 많아 진단이 어려운 경우가 많습니다. NCGS의 신경정신과적 증상의 병인은 흥미롭지만 아직까지 제대로 이해되지 않은 문제입니다. 이러한 질병의 유발 요인으로서 글루텐의 실제 역할을 규명하기 위해서는 잘 설계된 전향적 연구가 필요합니다.

Author Contributions

E.L., S.L. and M.R. observed the case and contributed to acquisition of data; E.L. and C.F. performed the review of literature and analyzed the data; E.L. and C.C. wrote the paper; and all authors contributed to revision of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Carlo Catassi served as consultant for Menarini diagnostics s.r.l., and for Shaer. Elena Lionetti served as consultant for Heinz Company.

References

- 1.Sapone A., Bai J.C., Ciacci C., Dolinsek J., Green P.H., Hadjivassiliou M., Kaukinen K., Rostami K., Sanders D.S., Schumann M., et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: Consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catassi C., Bai J.C., Bonaz B., Bouma G., Calabrò A., Carroccio A., Castillejo G., Ciacci C., Cristofori F., Dolinsek J., et al. Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: The new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:3839–3853. doi: 10.3390/nu5103839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volta U., Bardella M.T., Calabrò A., Troncone R., Corazza G.R., Study Group for Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Med. 2014;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fasano A., Sapone A., Zevallos V., Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1195–1204. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biagi F., Andrealli A., Bianchi P.I., Marchese A., Klersy C., Corazza G.R. A gluten-free diet score to evaluate dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2009;102:882–887. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509301579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genuis S.J., Lobo R.A. Gluten sensitivity presenting as a neuropsychiatric disorder. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/293206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francavilla R., Cristofori F., Castellaneta S., Polloni C., Albano V., Dellatte S., Indrio F., Cavallo L., Catassi C. Clinical, serologic, and histologic features of gluten sensitivity in children. J. Pediatr. 2014;164:463–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NICE . NICE Clinical Guidance 155. The British Psychological Society; Leicester, UK: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; London, UK: 2013. [(accessed on 2 April 2015)]. Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: Recognition and management. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG155. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohan F.C., Martin L., Grasberger J.C., Boehme D., Cottrell J.C. Antibodies to wheat gliadin in blood of psychiatric patients: Possible role of emotional factors. Biol. Psychiatry. 1972;5:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hekkens W.T.J.M. Antibodies to gliadin in serum of normals, coeliac patients & schizophrenics. In: Hemmings G., Hemmings W.A., editors. Biological Basis of Schizophrenia. 1st ed. MTP Press; Lancaster, PA, USA: 1978. pp. 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mascord I., Freed D., Durrant B. Antibodies to foodstuffs in schizophrenia. Br. Med. J. 1978;1:1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6123.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hekkens W.T.J.M., Schipperijn A.J.M., Freed D.L.J. Antibodies to wheat proteins in schizophrenia: Relationship or coincidence? In: Hemmings G., editor. Biochemistry of Schizophrenia & Addiction. 1st ed. MTP Press; Lancaster, PA, USA: 1980. pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuffin P., Gardiner P., Swinburne L.M. Schizophrenia, celiac disease, and anti- bodies to food. Biol. Psychiatry. 1981;16:281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugerman A.A., Southern D.L., Curran J.F. A study of antibody levels in alcoholic, depressive, and schizophrenic patients. Ann. Allergy. 1982;48:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rix K.J.B., Ditchfield J., Freed D.L.J., Goldberg D.P., Hillier V.F. Food antibodies in acute psychoses. Psychol. Med. 1985;15:347–354. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700023631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rybakowski J.K., Chorzelski T.P., Sulej J. Lack of IgA-class endomysial antibodies, the specific marker of gluten enteropathy. Med. Sci. Res. 1990;18:311. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichelt K.L., Landmark J. Specific IgA antibody increases in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1995;37:410–413. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peleg R., Ben-Zion Z.I., Peleg A., Gheber L., Kotler M., Weizman Z., Shiber A., Fich A., Horowitz Y., Shvartzman P. “Bread madness” revisited: Screening for specific celiac antibodies among schizophrenia patients. Eur. Psychiatry. 2004;19:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saetre P., Emilsson L., Axelsson E., Kreuger J., Lindholm E., Jazin E. Inflammation- related genes up-regulated in schizophrenia brains. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaroo D., Dickerson F., Kasarda D.D., Green P.H., Briani C., Yolken R.H., Alaedini A. Novel immune response to gluten in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2010;118:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickerson F., Stallings C., Origoni A., Vaughan C., Khushalani S., Leister F., Yang S., Krivogorsky B., Alaedini A., Yolken R. Markers of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease in recent-onset psychosis and multi-episode schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cascella N.G., Kryszak D., Bhatti B., Gregory P., Kelly D.K., mc Evoy J.P., Fasano A., Willimans W.W. Prevalence of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in the United States clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study population. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37:94–100. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidhom O., Laadhar L., Zitouni M., Ben Alaya N., Rafrafi R., Kallel-Sellami M., Makni S. Spectrum of autoantibodies in Tunisian psychiatric inpatients. Immunol. Investig. 2012;41:538–549. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.685537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin S.Z., Wu N., Xu Q., Zhang X., Ju G.Z., Law M.H., Wei J. A study of circulating gliadin antibodies in schizophrenia among a Chinese population. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38:514–518. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okusaga O., Yolken R.H., Langenberg P., Sleemi A., Kelly D.L., Vaswani D., Postolache T.T. Elevated gliadin antibody levels in individuals with schizophrenia. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;14:509–515. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2012.747699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cascella N.G., Santora D., Gregory P., Kelly D.L., Fasano A., Eaton W.W. Increased prevalence of transglutaminase 6 antibodies in sera from schizophrenia patients. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39:867–871. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lachance L.R., McKenzie K. Biomarkers of gluten sensitivity in patients with non-affective psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2014;152:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lionetti E., Francavilla R., Pavone P., Pavone L., Francavilla T., Pulvirenti A., Giugno R., Ruggieri M. The neurology of coeliac disease in childhood: What is the evidence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010;52:700–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadjivassiliou M., Sanders D.S., Grünewald R.A., Woodroofe N., Boscolo S., Aeschlimann D. Gluten sensitivity: From gut to brain. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:318–330. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70290-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadjivassiliou M., Grunewald R.A., Chattopadhyay A.K., Davies-Jones G.A., Gibson A., Jarratt J.A., Kandler R.H., Lobo A., Powell T., Smith C.M. Clinical, radiological, neurophysiological, and neuropathological characteristics of gluten ataxia. Lancet. 1998;352:1582–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickerson F., Stallings C., Origoni A., Vaughan C., Khushalani S., Alaedini A., Yolken R. Markers of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:52–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichelt K.L., Seim A.R., Reichelt W.H. Could schizophrenia be reasonably explained by Dohan’s hypothesis on genetic interaction with a dietary peptide overload? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;20:1083–1114. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(96)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y., Wan C., Li H., Zhu H., La Y., Xi Z., Chen Y., Jiang L., Feng G., He L. Altered levels of acute phase proteins in the plasma of patients with schizophrenia. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:3571–3576. doi: 10.1021/ac051916x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollis C. Adult outcomes of child and adolescent onset schizophrenia: Diagnostic stability and predictive validity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:1652–1659. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]