beyond reason

아플라톡신(Aflatoxin)은 Aspergillus flavus 등이 생산하는 곰팡이독으로 발암성이 있는 독성물질이다. 주로 산패한 호두, 땅콩, 캐슈넛, 피스타치오 등의 견과류에서 생긴다.

개요[편집]

아플라톡신은 토양, 썩어가는 식물, 건초 및 곡물에서 자라는 특정 곰팡이 (Aspergillus flavus 및 Aspergillus parasiticus)에 의해 생산되는 독성 및 암을 유발하는 화학물질이다. 그들은 정기적으로 카사바, 칠리 페퍼, 옥수수, 면실, 기장, 땅콩, 쌀, 참깨, 사탕수수, 해바라기씨, 견과류, 밀 등이 부적절하게 보관 된 제품에서 발견된다. 오염 된 식품이 처리 될 때, 아플라톡신은 일반 식품 공급 물에 들어가서 애완동물과 사람의 식품뿐만 아니라 축산동물용 사료에서도 발견된다. 오염된 사료를 섭취한 동물은 아플라톡신 변이 생성물을 알, 유제품 및 고기에 전달할 수 있다. [1] 예를 들어 오염 된 가금류 사료는 아플라톡신으로 오염 된 닭고기와 계란이 파키스탄에서 높은 비율로 발견된 것으로 의심된다.

특히 아플라톡신에 노출되면 성장 장애, 발달 지연, 간 손상 및 간암을 유발한다. 성인은 노출에 대한 내성이 높지만 안전하지는 않다. 동물은 면역이 없다. 아플라톡신은 알려진 가장 발암성이 강한 물질 중 하나이다. 몸에 들어가면 아플라톡신은 간에서 반응성 에폭시드 중간체로 대사되거나 덜 유해한 아플라톡신 M1이 되도록 하이드록실화 될 수 있다.

아플라톡신은 경구섭취가 일반적이며 가장 독성이 강한 아플라톡신B1은 피부를 통해 침투 할 수 있다.

식품 또는 사료에 함유된 아플라톡신의 미국 식품 의약청 (FDA) 조치 수준은 20 ~ 300ppb이다. [6] FDA는 노출방지를 위한 사전 예방조치로 인간과 애완동물의 오염된 식품에 대해 회수를 선언할 수 있다.

Aflatoxins: A Global Concern for Food Safety, Human Health and Their Management

Abstract

The aflatoxin producing fungi, Aspergillus spp., are widely spread in nature and have severely contaminated food supplies of humans and animals, resulting in health hazards and even death. Therefore, there is great demand for aflatoxins research to develop suitable methods for their quantification, precise detection and control to ensure the safety of consumers’ health.

Here, the chemistry and biosynthesis process of the mycotoxins is discussed in brief along with their occurrence, and the health hazards to humans and livestock(가축). This review focuses on resources, production, detection and control measures of aflatoxins to ensure food and feed safety. The review is informative for health-conscious consumers and research experts in the fields. Furthermore, providing knowledge on aflatoxins toxicity will help in ensure food safety and meet the future demands of the increasing population by decreasing the incidence of outbreaks due to aflatoxins.

Introduction

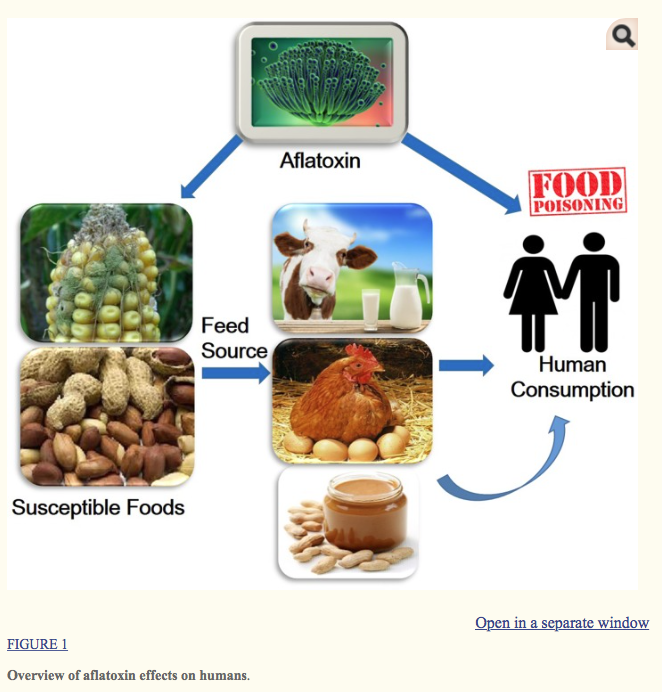

Aflatoxins are one of the highly toxic secondary metabolites derived from polyketides produced by fungal species such as Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius (Payne and Brown, 1998). These fungi usually infect cereal crops including wheat, walnut, corn, cotton, peanuts and tree nuts (Jelinek et al., 1989; Severns et al., 2003), and can lead to serious threats to human and animal health by causing various complications such as hepatotoxicity, teratogenicity, and immunotoxicity (Figure Figure11) (Amaike and Keller, 2011; Kensler et al., 2011; Roze et al., 2013). The major aflatoxins are B1, B2, G1, and G2, which can poison the body through respiratory, mucous or cutaneous routes, resulting in overactivation of the inflammatory response (Romani, 2004).

Food safety is one of the major problems currently facing the world; accordingly, a variety of studies have been conducted to discuss methods of addressing consumer concerns with various aspects of food safety (Nielsen et al., 2009). Since 1985, the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has restricted the amount of mycotoxins permitted in food products. The USDA Grain and Plant Inspection Service (GPIS) have implemented a service laboratory for inspection of mycotoxins in grains. Additionally, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) have recognized many toxins present in agricultural products. When mycotoxins are contaminated into foods, they cannot be destroyed by normal cooking processes. However, there have been many recent advances in food processing developed to keep final food products safe and healthy, such as hazard analysis of critical control points (HACCP) and good manufacturing practices (GMP; Lockis et al., 2011; Cusato et al., 2013; Maldonado-Siman et al., 2014). Moreover, several physical, chemical and biological methods can be applied to partially or completely eliminate these toxins from food and guarantee the food safety and health concerns of consumers. This review provides an overview of aflatoxigenic fungi, chemistry and biosynthesis of aflatoxins, along with their diversity in occurrence, and their health related risks to humans and livestock. Moreover, the effects of processing techniques on aflatoxins and various physical, chemical and biological methods for their control and management in food are discussed briefly.

Outbreaks Due to Aflatoxins

In 1974, a major outbreak of hepatitis due to aflatoxin was reported in the states of Gujrat and Rajasthan in India, resulting in an estimated 106 deaths (Krishnamachari et al., 1975). The outbreak lasted for 2 months and was confined to tribal people whose main staple food, maize, was later confirmed to contain aflatoxin. The preliminary analysis confirmed that consumption of A. flavus had occurred (Krishnamachari et al., 1975; Bhatt and Krishnamachari, 1978). Another outbreak of aflatoxin affecting both humans and dogs was reported in northwest India in 1974 (Tandon et al., 1977; Bhatt and Krishnamachari, 1978; Reddy and Raghavender, 2007). A major aflatoxin exposure outbreak was subsequently documented in Kenya in 1981 (Ngindu et al., 1982). Since 2004, multiple aflatoxicosis outbreaks have been reported worldwide, resulting in 500 acute illness and 200 deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDCP], 2004; Azziz-Baumgartner et al., 2005). Most outbreaks have been reported from rural areas of the East Province of Kenya in 2004 and occurred because of consumption of home grown maize contaminated with molds. Preliminary testing of food from affected areas revealed the presence of aflatoxin as reported in 1981 (Ngindu et al., 1982). In 2013, countries in Europe including Romania, Serbia, and Croatia reported the nationwide contamination of milk with aflatoxin1.

Major Source of Aflatoxin

The major sources of aflatoxins are fungi such as A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius (Kurtzman et al., 1987), although they are also produced by other species of Aspergillus as well as by Emericella spp. (Reiter et al., 2009). There are more than 20 known aflatoxins, but the four main ones are aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), aflatoxin B2 (AFB2), aflatoxin G1 (AFG1), and aflatoxin G2 (AFG2; Inan et al., 2007), while aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) and M2 (AFM2) are the hydroxylated metabolites of AFB1 and AFB2 (Giray et al., 2007; Hussain and Anwar, 2008).

Aspergillus spp.

The Aspergillus species are an industrially important group of microorganisms distributed worldwide. A. niger has been given Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status by the USFDA (Schuster et al., 2002). However, some species have negative impacts and cause diseases in grape, onion, garlic, peanut, maize, coffee, and other fruits and vegetables (Lorbeer et al., 2000; Magnoli et al., 2006; Waller et al., 2007; Rooney-Latham et al., 2008). Moreover, Aspergillus section nigri produces mycotoxins such as ochratoxins and fumonisins in peanut, maize, and grape (Astoreca et al., 2007a,b; Frisvad et al., 2007; Mogensen et al., 2009).

Plant–pathogen interactions have been studied using molecular markers such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) isolated from Aequorea victoria (Prasher et al., 1992). The GFP gene has been successfully inserted into Undifilum oxytropis (Mukherjee et al., 2010), Fusarium equiseti (Macia-Vicente et al., 2009), and Muscodor albus (Ezra et al., 2010) and utilized to study the expression of different proteins and production of mycotoxins. A. flavus and A. parasiticus infect many crops in the field, during harvest, in storage, and during processing. A. flavus is dominant in corn, cottonseed, and tree nuts, whereas A. parasiticus is dominant in peanuts. A. flavus consists of mycelium, conidia, or sclerotia and can grow at temperatures ranging between 12 and 48°C (Hedayati et al., 2007). A. flavus produces AFBI and AFB2, whereas A. parasiticus isolates produce AFGI, AFG2, AFM1, AFBI, and AFB2. A. flavus produces a number of airborne conidia and propagules that infect plants such as cotton (Lee et al., 1986). A high number of propagules was reported in soil, air, and on cotton leaves during mid- to late August, while soilborne inoculum increased drastically between April and December in cotton fields in Arizona (Ashworth et al., 1969). This fungus can even colonize moribund rye cover crop and peanut fruit debris (Griffin and Garren, 1976).

Aflatoxin (AFT)

Among the mycotoxins affecting food and feed, aflatoxin is the major one in food that ultimately harms human and animal health (Boutrif, 1998). The level of toxicity associated with aflatoxin varies with the types present, with the order of toxicity being AFTs-B1 > AFTs-G1 > AFTs-B2 > AFTs-G2 (Jaimez et al., 2000).

Chemistry and Biosynthesis of Aflatoxins

Chemically, aflatoxins (AFTs) are difuranocoumarin derivatives in which a bifuran group is attached at one side of the coumarin nucleus, while a pentanone ring is attached to the other side in the case of the AFTs and AFTs-B series, or a six-membered lactone ring is attached in the AFTs-G series (Bennett and Klich, 2003; Nakai et al., 2008). The physical, biological and chemical conditions of Aspergillus influence the production of toxins. Among the 20 identified AFTs, AFT-B1, and AFT-B2 are produced by A. flavus, while AFT-G1 and AFT-G2 along with AFT-B1 and AFT-B2 are produced by A. parasiticus (Bennett and Klich, 2003). AFT-B1, AFT-B2, AFT-G1, and AFT-G2 are the four major naturally produced aflatoxins (Pitt, 2000). AFTs-M1 and AFTs-M2 are derived from aflatoxin B types through different metabolic processes and expressed in animals and animal products (Weidenborner, 2001; Wolf-Hall, 2010). AFT-B1is highly carcinogenic (Squire, 1981), as well as heat resistant over a wide range of temperatures, including those reached during commercial processing conditions (Sirot et al., 2013).

The biosynthetic pathway of aflatoxins consists of 18 enzymatic steps for conversion from acetyl-CoA, and at least 25 genes encoding the enzymes and regulatory pathways have been cloned and characterized (Yu et al., 2002; Yabe and Nakajima, 2004). The gene comprises 70 kb of the fungal genome and is regulated by the regulatory gene, aflR (Yabe and Nakajima, 2004; Yu et al., 2004; Price et al., 2006). The metabolic grid involved in the aflatoxin biosynthesis (Yabe et al., 1991, 2003). Hydroxyversicolorone (HVN) is converted to versiconal hemiacetal acetate (VHA) by a cytosol monooxygenase, in which NADPH is a cofactor (Yabe et al., 2003). Monooxygenase is encoded by the moxY gene, which catalyzes the conversion of HVN to VHA and the accumulation of HVN and versicolorone (VONE) occurs in the absence of the moxY gene (Wen et al., 2005).

Gene Responsible for Aflatoxin Production

Various genes and their enzymes are involved in the production of sterigmatocystin (ST) dihydrosterigmatocystin (DHST), which are the penultimate precursors of aflatoxins (Cole and Cox, 1987). The aflatoxin biosynthesis gene nor-1, which was first cloned in A. Parasiticus, is named after the product formed by the gene during biosynthesis (Chang et al., 1992). These genes named according to substrate and the product formed nor-1 (norsolorinic acid [NOR]), norA, norB, avnA (averanti [AVN]), avfA(averufin [AVF]), ver-1 (versicolorin A [VERA]), verA and verB while those based on enzyme functions fas-2 (FAS alpha subunit), fas-1 (FAS beta subunit), pksA (PKS), adhA (alcohol dehydrogenase), estA(esterase), vbs (VERB synthase), dmtA (mt-I; O-methyltransferase I), omtA (O-methyltransferase A), ordA(oxidoreductase A), cypA (cytochrome P450 monooxygenase), cypX (cytochrome P450 monooxygenase), and moxY (monooxygenase). Initially, the aflatoxin regulatory gene was named afl-2 in A. flavus (Payne et al., 1993) and apa-2 in A. parasiticus (Chang et al., 1993). However, it was subsequently referred to as aflRin A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nidulans because of its role as a transcriptional activator. Previous studies have shown that aflA (fas-2), aflB (fas-1), and aflC (pksA) are responsible for the conversion of acetate to NOR (Townsend et al., 1984; Brown et al., 1996). Moreover, the uvm8 gene was shown to be essential for NOR biosynthesis as well as aflatoxin production in A. parasiticus. The amino acid of sequence of the gene is similar to that of the beta subunit of FASs (FAS1) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae(Trail et al., 1995a,b). FAS forms the polyketide backbone during aflatoxin synthesis; hence, the uvm8 gene was named fas-1 (Mahanti et al., 1996). Fatty acid syntheses (FASs) is responsible for sterigmatocystin (ST) biosynthesis in A. nidulans and further identified two genes viz., stcJ and stcK that encode FAS and FAS subunits (FAS-2 and FAS-1; Brown et al., 1996).

Occurrence in Food

Aflatoxins are found in various cereals, oilseeds, spices, and nuts (Lancaster et al., 1961; Weidenborner, 2001; Reddy, 2010; Iqbal et al., 2014). These Aspergillus colonize among themselves and produce aflatoxins, which contaminate grains and cereals at various steps during harvesting or storage. Fungal contamination can occur in the field, or during harvest, transport and storage (Kader and Hussein, 2009). Aflatoxins contamination of wheat or barley is commonly happen by the result of inappropriate storage (Jacobsen, 2008). In milk, aflatoxins is generally at 1–6% of the total content in the feedstuff (Jacobsen, 2008). AFTs infect humans following consumption of aflatoxins contaminated foods such as eggs, meat and meat products, milk and milk products, (Bennett and Klich, 2003; Piemarini et al., 2007).

Effects on Agriculture and Food

Mycotoxins, including aflatoxin, have affected most crops grown worldwide; however, the extent of aflatoxin toxicity varies according to the commodities (Abbas et al., 2010). Aflatoxin can infect crops during growth phases or even after harvesting (Kumar et al., 2008). Exposure to this toxin poses serious hazards to human health (Umoh et al., 2011). Commodities such as corn, peanuts, pistachio, Brazil nuts, copra, and coconut are highly prone to contamination by aflatoxin (Idris et al., 2010; Cornea et al., 2011), whereas wheat, oats, millet, barley, rice, cassava, soybeans, beans, pulses, and sorghum are usually resistant to aflatoxin contamination. However, agricultural products such as cocoa beans, linseeds, melon seeds and sunflower seeds are seldom contaminated (Bankole et al., 2010). Aflatoxin was on the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) of the European Union in 2008 because of its severe effects (European Commission, 2009), and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) later categorized AFB1 as a group I carcinogen for humans (Seo et al., 2011). Despite several research and control measures, aflatoxin is still a major threat to food and agricultural commodities.

Mechanism of Toxicity and Health Effects by Aflatoxin

Aflatoxin are specifically target the liver organ (Abdel-Wahhab et al., 2007). Early symptoms of hepatotoxicity of liver caused by aflatoxins comprise fever, malaise and anorexia followed with abdominal pain, vomiting, and hepatitis; however, cases of acute poisoning are exceptional and rare (Etzel, 2002). Chronic toxicity by aflatoxins comprises immunosuppressive and carcinogenic effects. Evaluation of the effects of AFT-B1 on splenic lymphocyte phenotypes and inflammatory cytokine expression in male F344 rats have been studied (Qian et al., 2014). AFT-B1 reduced anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 expression, but increased the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ and TNF-α expression by NK cells. These findings indicate that frequent AFT-B1 exposure accelerates inflammatory responses via regulation of cytokine gene expression. Furthermore, Mehrzad et al. (2014) observed that AFT-B1 interrupts the process of antigen-presenting capacity of porcine dendritic cells, suggested this perhaps one of mechanism of immunotoxicity by AFT-B1.

Aflatoxins cause reduced efficiency of immunization in children that lead to enhanced risk of infections (Hendrickse, 1997). The hepatocarcinogenicity of aflatoxins is mainly due to the lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage to DNA (Verma, 2004). AFTs-B1 in the liver is activated by cytochrome p450 enzymes, which are converted to AFTs-B1-8, 9-epoxide, which is responsible for carcinogenic effects in the kidney (Massey et al., 1995). Among all major mycotoxins, aflatoxins create a high risk in dairy because of the presence of their derivative, AFTs-M1, in milk, posing a potential health hazard for human consumption (Van Egmond, 1991; Wood, 1991). AFTs-B1 is rapidly absorbed in the digestive tract and metabolized by the liver, which converts it to AFT-M1 for subsequent secretion in milk and urine (Veldman et al., 1992). Although AFTs-M1 is less mutagenic and carcinogenic than AFTs-B1, it exhibits high genotoxic activity. The other effects of AFTs-M1 include liver damage, decreased milk production, immunity suppression and reduced oxygen supply to tissues due to anemia (Aydin et al., 2008), which reduces appetite and growth in dairy cattle (Akande et al., 2006). Several studies have shown the detrimental effects of aflatoxins exposure on the liver (Sharmila Banu et al., 2009), epididymis (Agnes and Akbarsha, 2001), testis (Faisal et al., 2008), kidney and heart (Mohammed and Metwally, 2009; Gupta and Sharma, 2011). It has been found that aflatoxin presences in post-mortem brain tissue (Oyelami et al., 1995), suggested that its ability to cross the blood brain barrier (Qureshi et al., 2015). AFTs also cause abnormalities in the structure and functioning of mitochondrial DNA and brain cells (Verma, 2004). The effects of aflatoxin on brain chemistry have been reviewed in details by Bbosa et al. (2013). Furthermore, few reports have described the effects of AFTs-B1 administration on the structure of the rodent central nervous system (Laag and Abdel Aziz, 2013).

The liver toxicology of aflatoxin is also a critical issue (IARC, 2002; Iqbal et al., 2014). Limited doses are not harmful to humans or animals; however, the doses that do cause-effects diverse among Aflatoxin groups. The expression of aflatoxin toxicity is regulated by factors such as age, sex, species, and status of nutrition of infected animals (Williams et al., 2004). The symptoms of acute aflatoxicosis include oedema, haemorrhagic necrosis of the liver and profound lethargy, while the chronic effects are immune suppression, growth retardation, and cancer (Gong et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2004; Cotty and Jaime-Garcia, 2007).

Effects of Processing on Aflatoxin

Techniques to eliminate aflatoxin may be either physical or chemical methods. Removing mold-damaged kernels, seeds or nuts physically from commodities has been observed to reduce aflatoxins by 40–80% (Park, 2002). The fate of aflatoxin varies with type of heat treatment (e.g., cooking, drying, pasteurization, sterilization, and spray drying; Galvano et al., 1996). Aflatoxins decompose at temperatures of 237–306°C (Rustom, 1997); therefore, pasteurization of milk cannot protect against AFM1 contamination. Awasthi et al. (2012) reported that neither pasteurization nor boiling influenced the level of AFM1 in bovine milk. However, boiling corn grits reduced aflatoxins by 28% and frying after boiling reduced their levels by 34–53% (Stoloff and Trucksess, 1981). Roasting pistachio nuts at 90°C, 120°C, and 150°C for 30, 60 and 120 min was found to reduce aflatoxin levels by 17–63% (Yazdanpanah et al., 2005). The decrease in aflatoxin content depends on the time and temperature combination.

Moreover, alkaline cooking and steeping of corn for the production of tortillas reduces aflatoxin by 52% (Torres et al., 2001). Hameed (1993) reported reductions in aflatoxin content of 50–80% after extrusion alone. When hydroxide (0.7 and 1.0%) or bicarbonate (0.4%) was added, the reduction was enhanced to 95%. Similar results were reported by Cheftel (1989) for the extrusion cooking of peanut meal. The highest aflatoxin reduction was found to be 59% with a moisture content of 35% in peanut meal, and the extrusion variables non-significantly affected its nutritional composition (Saalia and Phillips, 2011a). Saalia and Phillips (2011b) reported an 84% reduction in aflatoxin of peanut meal when cooked in the presence of calcium chloride.

Effects of Environmental Temperature on Aflatoxin Production

Climate change plays a major role in production of aflatoxin from Aspergillus in food crops (Paterson and Lima, 2010, 2011; Magan et al., 2011; Wu F. et al., 2011; Wu S. et al., 2011). Climate change affects the interactions between different mycotoxigenic species and the toxins produced by them in foods and feeds (Magan et al., 2010; Paterson and Lima, 2012). Changes in environmental temperature influence the expression levels of regulatory genes (aflR and aflS) and aflatoxin production in A. flavus and A. parasiticus (Schmidt-Heydt et al., 2010, 2011). A good correlation between the expression of an early structural gene (aflD) and AFB1 has been reported by Abdel-Hadi et al. (2010). Temperature interacts with water activity (aw) and influences the ratio of regulatory genes (aflR/aflS), which is directly proportional to the production of AFB1 (Schmidt-Heydt et al., 2009, 2010). The interactions between water activity and temperature have prominent effect on Aspergillus spp. and aflatoxin production (Sanchis and Magan, 2004; Magan and Aldred, 2007). Increasing the temperature to 37°C and water stress significantly reduces the production of AFB1 produced, despite the growth of A. flavus under these conditions. The addition of CO2under the same temperature and water activity enhances AFB1 production (Medina et al., 2014). According to Gallo et al. (2016), fungal biomass and AFB1 production were reported to be highest at 28°C and 0.96 aw, while no fungal growth or AFB1 production was seen at 20°C with aw values of 0.90 and 0.93. There was also no AFB1 production observed at 37°C. Reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR also revealed that the regulatory genes aflR and aflS were highly expressed at 28°C, while the lowest expression was observed at 20 and 37°C, suggesting that temperature plays a significant role in gene expression and aflatoxin production (Gallo et al., 2016).

Detection Techniques

The detection and quantification of aflatoxin in food and feed is a very important aspect for the safety concerns. Aflatoxins are usually detected and identified according to their absorption and emission spectra, with peak absorbance occurring at 360 nm. B toxins exhibit blue fluorescence at 425 nm, while G toxins show green fluorescence at 540 nm under UV irradiation. This florescence phenomenon is widely accepted for aflatoxins. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) is among one of the oldest techniques used for aflatoxin detection (Fallah et al., 2011), while high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LCMS), and enzyme linked immune-sorbent assay (ELISA) are the methods most frequently used for its detection (Tabari et al., 2011; Andrade et al., 2013; Sulyok et al., 2015). ELISA can be used to identify aflatoxins based on estimation of AfB1-lysine (metabolite of AFB1 toxin) concentration in the blood. Specifically, the test detects levels of AfB1 in blood as low as 5 pg/mg albumin, making it a cost effective method for routine monitoring that can also be utilized for the detection of hepatitis B virus. Room temperature phosphorescence (RTP) in aflatoxigenic strains grown on media is commonly used in food mycology. Aflatoxins immobilized on resin beads can induce RTP in the presence or absence of oxygen and heavy atoms (Costa-Fernandez and Sanz-Medel, 2000) and also have high sensitivity and specificity (Li et al., 2003). Moreover, several biosensors and immunoassays have been developed to detect ultra-traces of aflatoxins to ensure the food safety.

Degradation Kinetics

Various treatments including chemical, physical, and biological methods are routinely utilized for effective degradation, mitigation and management of aflatoxin (Shcherbakova et al., 2015). The aflatoxins AFB1 and AFG1 are completely removed by ozone treatment at 8.5–40 ppm at different temperatures, but AFB2 and AFG2 are not affected by this method. The degradation of aflatoxin followed first order kinetic equation. However, microbial and enzymatic degradation is preferred for the biodegradation of aflatoxin due to its eco-friendly nature (Agriopoulou et al., 2016). The bacterium Flavobacterium aurantiacumreportedly removes AFM1 from milk and Nocardia asteroides transforms AFB1 to fluorescent product (Wu et al., 2009). Rhodococcus species are able to degrade aflatoxins (Teniola et al., 2005) and their ability to degrade AFB1 occurs in the following order: R. ruber < R. globerulus < R. coprophilus < R. gordoniae < R. pyridinivorans and < R. erythropolis (Cserhati et al., 2013). Fungi such as Pleurotus ostreatus, Trametes versicolor, Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans, S. cerevisiae, Trichoderma strains, and Armillariella tabescensare known to transform AFB1 into less toxic forms (Guan et al., 2008). Zhao et al. (2011) reported purification of extracellular enzymes from the bacterium Myxococcus fulvus ANSM068 with a final specific activity of 569.44 × 103 U/mg. The pure enzyme (100 U/mL) had a degradation ability of 96.96% for AFG1 and 95.80% for AFM1 after 48 h of incubation. Moreover, the recombinant laccase produced by A. niger D15-Lcc2#3 (118 U/L) was found to lead to a decrease in AFB1 of 55% within 72 h (Alberts et al., 2009).

Management and Control Strategies

The biocontrol principle of competitive exclusion of toxigenic strains of A. flavus involves the use of non-toxigenic strains to reduce aflatoxin contamination in maize (Abbas et al., 2006). The use of biocontrol agents such as Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Ralstonia spp., and Burkholderiaspp. are effective at control and management of aflatoxins (Palumbo et al., 2006). Several strains of B. subtilis and P. solanacearum isolated from the non-rhizosphere of maize soil have been reported to eliminate aflatoxin (Nesci et al., 2005). Biological control of aflatoxin production in crops in the US has been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency and two commercial products based on atoxigenic A. flavus strains are being used (Afla-guard® and AF36®) for the prevention of aflatoxin in peanuts, corn, and cotton seed (Dorner, 2009). Good agricultural practices (GAPs) also help control the toxins to a larger extent, such as timely planting, providing adequate plant nutrition, controlling weeds, and crop rotation, which effectively control A. flavus infection in the field (Ehrlich and Cotty, 2004; Waliyar et al., 2013).

Biological control is emerging as a promising approach for aflatoxin management in groundnuts using Trichoderma spp, and significant reductions of 20–90% infection of aflatoxin have been recorded (Anjaiah et al., 2006; Waliyar et al., 2015). Use of inbred maize lines resistant to aflatoxin has also been employed. Potential biochemical markers and genes for resistance in maize against Aspergillus could also be utilized (Chen et al., 2007). Additionally, biotechnological approaches have been reviewed for aflatoxin management strategies (Yu, 2012). Advances in genomic technology based research and decoding of the A. flavus genome have supported identification of the genes responsible for production and modification of the aflatoxin biosynthesis process (Bhatnagar et al., 2003; Cleveland, 2006; Holbrook et al., 2006; Ehrlich, 2009). In addition, Wu (2010) suggested that aflatoxin accumulation can be reduced by utilizing transgenic Bt maize with insect resistance traits as the wounding caused by insects helps penetrate the Aspergillus in kernels.

Conclusion

Aflatoxins are a major source of disease outbreaks due to a lack of knowledge and consumption of contaminated food and feed worldwide. Excessive levels of aflatoxins in food of non-industrialized countries are of major concern. Several effective physical, chemical, biological, and genetic engineering techniques have been employed for the mitigation, effective control and management of aflatoxins in food. However, developing fungal resistant and insect resistant hybrids/crops to combat pre-harvest infections and their outcome is a major issue of concern. Post-harvest treatments to remove aflatoxins such as alkalization, ammonization, and heat or gamma radiation are not generally used by farmers. However, some of the microorganisms naturally present in soil have the ability to degrade and reduce the aflatoxin contamination in different types of agricultural produce. Therefore, methods of using these organisms to reduce aflatoxin are currently being focused on. Moreover, application of genetic recombination in A. flavus and other species is being investigated for its potential to mitigate aflatoxins to ensure the safety and quality of food.

Author Contributions

PK and DM designed and conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript. MK, TM, and SK edited and helped in finalizing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

PK and MK highly grateful to the Director and Head, Department of Forestry, NERIST (Deemed University), Arunachal Pradesh, India. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2009-0070065).

References

- Abbas H. K., Reddy K. R. N., Salleh B., Saad B., Abel C. A., Shier W. T. (2010). An overview of mycotoxin contamination in foods and its implications for human health. Toxin Rev. 29 3–26. 10.3109/15569541003598553 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas H. K., Zablotowicz R. M., Bruns H. A., Abel C. A. (2006). Biocontrol of aflatoxin in corn by inoculation with non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 16 437–449. 10.1080/09583150500532477 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hadi A., Carter D., Magan N. (2010). Temporal monitoring of the nor-1 (aflD) gene of Aspergillus flavus in relation to aflatoxin B1 production during storage of peanuts under different environmental conditions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109 1914–1922. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04820.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahhab M. A., Abdel-Galil M. M., Hassan A. M., Hassan N. H., Nada S. A., Saeed A., et al. (2007). Zizyphus spina-christi extract protects against aflatoxin B1-intitiated hepatic carcinogenicity. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 4 248–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnes V. F., Akbarsha M. A. (2001). Pale vacuolated epithelial cells in epididymis of aflatoxin-treated mice. Reproduction 122 629–641. 10.1530/rep.0.1220629 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Agriopoulou S., Koliadima A., Karaiskakis G., Kapolos J. (2016). Kinetic study of aflatoxins’ degradation in the presence of ozone. Food Control 61 221–226. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.09.013 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Akande K. E., Abubakar M. M., Adegbola T. A., Bogoro S. E. (2006). Nutritional and health implications of mycotoxin in animal feed. Pak. J. Nutr. 5 398–403. 10.3923/pjn.2006.398.403 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts J. F., Gelderblom W. C. A., Botha A., van Zyl W. H. (2009). Degradation of aflatoxin B1 by fungal laccase enzymes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 135 47–52. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.022 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Amaike S. A., Keller N. P. (2011). Aspergillus flavus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49 107–133. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095221 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade P. D., da Silva J. L. G., Caldas E. D. (2013). Simultaneous analysis of aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, G2, M1 and ochratoxin A in breast milk by high-performance liquid chromatography/fluorescence after liquid-liquid extraction with low temperature purification (LLE-LTP). J. Chromatogr. A 1304 61–68. 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.06.049 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anjaiah V., Thakur R. P., Koedam N. (2006). Evaluation of bacteria and Trichoderma for biocontrol of pre-harvest seed infection by Aspergillus flavus in groundnut. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 16 431–436. 10.1080/09583150500532337 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth L. J., Jr., McMeans J. L., Brown C. M. (1969). Infection of cotton by Aspergillus flavus: epidemiology of the disease. J. Stored Prod. Res. 5 193–202. 10.1016/0022-474X(69)90033-2 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Astoreca A., Magnoli C., Barberis C., Chiacchiera S. M., Combina M., Dalcero A. (2007a). Ochratoxin A production in relation to ecophysiological factors by Aspergillus section Nigri strains isolated from different substrates in Argentina. Sci. Total Environ. 388 16–23. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.07.028 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Astoreca A., Magnoli C., Ramirez M. L., Combina M., Dalcero A. (2007b). Water activity and temperature effects on growth of Aspergillus niger, A. awamori and A. Carbonarius isolated from different substrates in Argentina. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 119 314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi V., Bahman S., Thakur L. K., Singh S. K., Dua A., Ganguly S. (2012). Contaminants in milk and impact of heating: an assessment study. Indian J. Public Health 56 95–99. 10.4103/0019-557X.96985 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin A., Gunsen U., Demirel S. (2008). Total aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A levels in Turkish wheat flour. J. Food Drug Anal. 16 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Azziz-Baumgartner E., Lindblade K., Gieseker K., Rogers H. S., Kieszak S., Njapau H., et al. (2005). Case–control study of an acute aflatoxicosis outbreak, Kenya, 2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 113 1779–1783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole S. A., Adenusi A. A., Lawal O. S., Adesanya O. O. (2010). Occurrence of aflatoxin B1 in food products derivabl e from ‘egusi’ melon seeds consumed in southwestern Nigeria. Food Control 21 974–976. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.11.014 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bbosa G. S., Kitya D., Lubega A., Ogwal-Okeng J., Anokbonggo W. W., Kyegombe D. B. (2013). “Review of the biological and health effects of aflatoxins on bodyorgans and body systems,” inAflatoxins – Recent Advances and Future Prospects, ed. Razzaghi-Abyaneh M., editor. (Rijeka: InTech; ), 239–265. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. W., Klich M. (2003). Mycotoxins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16 497–516. 10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar D., Ehrlich K. C., Cleveland T. E. (2003). Molecular genetic analysis and regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61 83–93. 10.1007/s00253-002-1199-x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt R. V., Krishnamachari K. A. V. R. (1978). Food toxins and disease outbreaks in India.Arogya J. Health Sci. 4 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Boutrif E. (1998). Prevention of aflatoxin in pistachios. Food Nutr. Agric. 21 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. W., Adams T. H., Keller N. P. (1996). Aspergillus has distinct fatty acid synthases for primary and secondary metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 19 14873–14877. 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14873 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDCP] (2004). Outbreak of Aflatoxin Poisoning — Eastern and Central Provinces, Kenya, January—July 2004. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5334a4.htm [accessed October 10 2016] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P. K., Cary J. W., Bhatnagar D., Cleveland T. E., Bennett J. W., Linz J. E., et al. (1993). Cloning of the Aspergillus parasiticus apa-2 gene associated with the regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 3273–3279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P. K., Skory C. D., Linz J. E. (1992). Cloning of a gene associated with aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Curr. Genet. 21 231–233. 10.1007/BF00336846 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cheftel J. C. (1989). “Extrusion cooking and food safety,” in Extrusion Cooking, eds Mercier C., Linko P., Harper J. M., editors. (Eagan, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists; ), 435–461. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Brown R. L., Damann K. E., Cleveland T. E. (2007). Identification of maiz kernel endosperm proteins associated with resistance to aflatoxin contamination by Aspergillus flavus.Phytopathology 97 1094–1103. 10.1094/PHYTO-97-9-1094 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland T. E. (2006). “The use of crop proteomics and fungal genomics inelucidating fungus–crop interactions,” in Proceedings of the Myco-Globe Conference, Bari, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Cole R. J., Cox E. H. (1987). Handbook of Toxic Fungal Metabolites. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornea C. P., Ciuca M., Voaides C., Gagiu V., Pop A. (2011). Incidence of fungal contamination in a Romanian bakery: a molecular approach. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 16 5863–5871. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Fernandez J. M., Sanz-Medel A. (2000). Room temperature phosphorescence biochemical sensors. Quim. Anal. 19 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cotty P. J., Jaime-Garcia R. (2007). Influences of climate on aflatoxin producing fungi and aflatoxin contamination. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 119 109–115. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.060 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cserhati M., Kriszt B., Krifaton C., Szoboszlay S., Hahn J., Toth S., et al. (2013). Mycotoxin-degradation profile of Rhodococcus strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 166 176–185. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.06.002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cusato S., Gameiro A. H., Corassin C. H., Sant’Ana A. S., Cruz A. G., Faria J. D. A. F., et al. (2013). Food safety systems in a small dairy factory: implementation, major challenges, and assessment of systems’ performances. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10 6–12. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1286 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner J. W. (2009). Development of biocontrol technology to manage aflatoxin contamination in peanuts. Peanut Sci. 36 60–67. 10.3146/AT07-002.1 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich K. C. (2009). Predicted roles of uncharacterized clustered genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis.Toxins 1 37–58. 10.3390/toxins1010037 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich K. K., Cotty P. J. (2004). An isolate of Aspergillus flavus used to reduce aflatoxin contamination in cottonseed has a defective polyketide synthase gene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 65 473–478. 10.1007/s00253-004-1670-y [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Etzel R. A. (2002). Mycotoxins. JAMA 287 425–427. 10.1001/jama.287.4.425 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2009). The Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2008. Luxembourg: European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Ezra D., Skovorodnikova J., Kroitor-Keren T., Denisov Y., Liarzi O. (2010). Development of methods for detection and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the sterile, endophytic fungus Muscodor albus. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 20 83–97. 10.1080/09583150903420049 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal K., Periasamy V. S., Sahabudeen S., Radha A., Anandhi R., Akbarsha M. A. (2008). Spermatotoxic effect of aflatoxin B1 in rat: extrusion of outer densefibres and associated axonemal microtubule doublets of sperm flagellum. Reproduction 135 303–310. 10.1530/REP-07-0367 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah A. A., Rahnama M., Jafari T., Saei-Dehkordi S. S. (2011). Seasonal variation of aflatoxin M1 contamination in industrial and traditional Iranian dairy products. Food Control 22 1653–1656. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.03.024 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J. C., Smedsgaard J., Samson R. A., Larsen T. O., Thrane U. (2007). Fumonisin B2 Production by Aspergillus niger. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55 9727–9732. 10.1021/jf0718906 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A., Solfrizzo M., Epifani F., Panzarini G., Perrone G. (2016). Effect of temperature and water activity on gene expression and aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus on almond medium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 217 162–169. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.026 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Galvano F., Galofaro V., Galvano G. (1996). Occurrence and stability of aflatoxin M1 in milk and milk products. A worldwide review. J. Food Prot. 59 1079–1090. 10.4315/0362-028X-59.10.1079 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Giray B., Girgin G., Engin A. B., Aydın S., Sahin G. (2007). Aflatoxin levels in wheat samples consumed in some regions of Turkey. Food Control 18 23–29. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.08.002 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Hounsa A., Egal S., Turner P. C., Sutcliffe A. E., Hall A. J., et al. (2004). Postweaning exposure to aflatoxin results in impaired child growth: a longitudinal study in Benin, West Africa. Environ. Health Perspect. 112 1334–1338. 10.1289/ehp.6954 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin G. J., Garren K. H. (1976). Colonization of rye green manure and peanut fruit debris by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus niger group in field soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32 28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S., Ji C., Zhou T., Li J., Ma Q., Niu T. (2008). Aflatoxin B1 degradation by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and other microbes selected using coumarin medium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 9 1489–1503. 10.3390/ijms9081489 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Sharma V. (2011). Ameliorative effects of tinospora cordifolia root extracton histopathological and biochemical changes induced by aflatoxin-b (1) in mice kidney. Toxicol. Int.18 94–98. 10.4103/0971-6580.84259 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed H. G. (1993). Extrusion and Chemical Treatments for Destruction of Aflatoxin in Naturally-Contaminated Corn. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayati M. T., Pasqualotto A. C., Warn P. A., Bowyer P., Denning D. W. (2007). Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and micotoxin producer. Microbiology 153 1677–1692. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007641-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickse R. G. (1997). Of sick Turkeys, Kwashiorkor, malaria, perinatal mortality, Herion addicts and food poisoning: research on influence of aflatoxins on child health in the tropics. J. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 91 87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook C. C., Jr., Guo B., Wilson D. M., Timper P. (2006). “The U.S. breeding program to develop peanut with drought tolerance and reduced aflatoxin contamination [abstract],” inProceedings of the International Conference on Groundnut Aflatoxin Management and Genomics, Guangzhou. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain I., Anwar J. (2008). A study on contamination of aflatoxin M1 in raw milk in the Punjab province of Pakistan. Food Control 19 393–395. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.12.002 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2002). Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 82. Lyon: International Agency for Cancer Research. [Google Scholar]

- Idris Y. M. A., Mariod A. A., Elnour I. A., Mohamed A. A. (2010). Determination of aflatoxin levels in Sudanese edible oils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48 2539–2541. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.021 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inan F., Pala M., Doymaz I. (2007). Use of ozone in detoxification of aflatoxin B1 in red pepper.J. Stored Prod. Res. 43 425–429. 10.1016/j.jspr.2006.11.004 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal S. Z., Mustafa H. G., Asi M. R., Jinap S. (2014). Variation in vitamin E level and aflatoxins contamination in different rice varieties. J. Cereal Sci. 60 352–355. 10.1016/j.jcs.2014.05.012 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen B. J. (2008). “Predicting the Incidence of Mycotoxins,” in Proceeding of 26th Annual International Symposium on Man and His Environment in Health and Disease: Molds & Mycotoxins, Hidden Connections for Chronic Diseases, (Dallas, TX: American Environmental Health Foundation), 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimez J., Fente C. A., Vazquez B. I., Franco C. M., Cepeda A., Mahuzier G., et al. (2000). Application of the assay of aflatoxins by liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection in food analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 882 1–10. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00212-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek C. F., Pohland A. E., Wood G. E. (1989). Worldwide occurrence of mycotoxins in foods and feeds – an update. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 72 223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kader A. A., Hussein A. M. (2009). Harvesting and Postharvest Handling of Dates. Aleppo: ICARDA. [Google Scholar]

- Kensler T. W., Roebuck B. D., Wogan G. N., Groopman J. D. (2011). Aflatoxin: a 50-year odyssey of mechanistic and translational toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 120 28–48. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq283 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamachari K. A. V. R., Bhat R. V., Nagarajan V., Tilak T. B. G. (1975). Hepatitis due to aflatoxicosis-An outbreak in western India. Lancet 1 1061–1063. 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)91829-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]