The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway coordinates cell

작성자문형철작성시간20.11.03조회수1,707 목록 댓글 0beyond reason

영향력지수 20점 논문

AMPK는 세포내 ATP가 떨어지면 활성화되는 장수유전자

AMPK는 세포성장, 대사의 재설계 조절에 중요한 역할을 함.

AMPK promotes catabolic pathways to generate more ATP, and inhibits anabolic pathways.

- ampk는 음식물의 이화작용을 촉진하여 ATP를 생성하고 동화작용을 억제함.

Hesperetin is a potent bioactivator that activates SIRT1-AMPK signaling pathway in HepG2 cells

- Hajar Shokri Afra,

- Mohammad Zangooei,

- Reza Meshkani,

- Mohammad Hossein Ghahremani,

- Davod Ilbeigi,

- Azam Khedri,

- Shiva Shahmohamadnejad,

- Shahnaz Khaghani &

- Mitra Nourbakhsh

Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry volume 75, pages125–133(2019)Cite this article

- 391 Accesses

- 6 Citations

- 1 Altmetric

- Metricsdetails

Abstract

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is a deacetylase enzyme that plays crucial roles in controlling many cellular processes and its downregulation has been implicated in different metabolic disorders. Recently, several polyphenols have been considered as the effective therapeutic approaches that appear to influence SIRT1. The main goal of this study was to evaluate the effect of hesperetin, a citrus polyphenolic flavonoid, on SIRT1 and AMP-activated kinase (AMPK). HepG2 cells were treated with hesperetin in the presence or absence of EX-527, a SIRT1 specific inhibitor, for 24 h. Resveratrol was used as a positive control. SIRT1 gene expression, protein level, and activity were measured by RT-PCR, Western blotting, and fluorometric assay, respectively. AMPK phosphorylation was also determined by Western blotting. Our results indicated a significant increase in SIRT1 protein level and activity as well as an induction of AMPK phosphorylation by hesperetin. These effects of hesperetin were abolished by EX-527. Furthermore, hesperetin reversed the EX-527 inhibitory effects on SIRT1 protein expression and AMPK phosphorylation. These findings suggest that hesperetin can be a novel SIRT1 activator, even stronger than resveratrol. Therefore, the current study may introduce hesperetin as a new strategy aimed at upregulation SIRT1-AMPK pathway resulting in various cellular processes regulation.

Nat Cell Biol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 Mar 2.

Published in final edited form as:

Nat Cell Biol. 2011 Sep 2; 13(9): 1016–1023.

Published online 2011 Sep 2. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329

PMCID: PMC3249400

NIHMSID: NIHMS341890

PMID: 21892142

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy, & metabolism

Maria M. Mihaylova and Reuben J. Shaw

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

The publisher's final edited version of this article is available at Nat Cell Biol

See other articles in PMC that cite the published article.

Associated DataSupplementary Materials

Abstract

One of the central regulators of cellular and organismal metabolism in eukaryotes is the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is activated when intracellular ATP levels lower. AMPK plays critical roles in regulating growth and reprogramming metabolism, and recently has been connected to cellular processes including autophagy and cell polarity. We review here a number of recent breakthroughs in the mechanistic understanding of AMPK function, focusing on a number of new identified downstream effectors of AMPK.

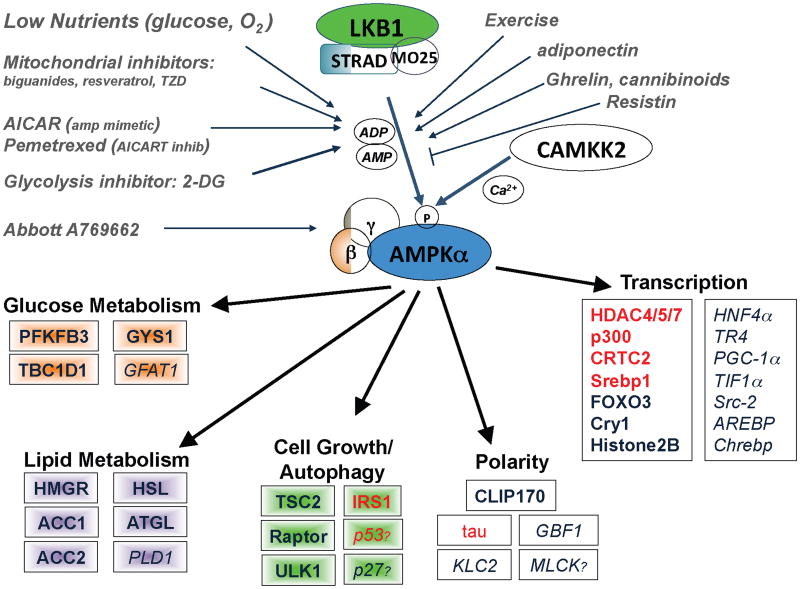

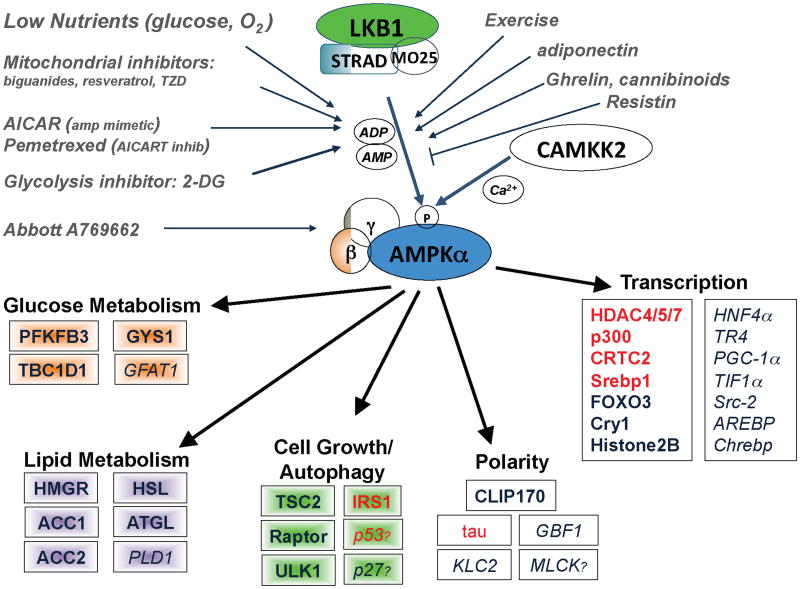

Core AMPK complex Components and Upstream Activators

One of the fundamental requirements of all cells is to balance ATP consumption and ATP generation. AMPK is a highly conserved sensor of intracellular adenosine nucleotide levels that is activated when even modest decreases in ATP production result in relative increases in AMP or ADP. In response, AMPK promotes catabolic pathways to generate more ATP, and inhibits anabolic pathways. Genetic analysis of AMPK orthologs in Arabidopsis1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae2, Dictyostelium3, C. elegans4, Drosophila5, and even the moss Physcomitrella patens6 has revealed a conserved function of AMPK as a metabolic sensor, allowing for adaptive changes in growth, differentiation, and metabolism under conditions of low energy. In higher eukaryotes like mammals, AMPK plays a general role in coordinating growth and metabolism, and specialized roles in metabolic control in dedicated tissues such as the liver, muscle and fat7.

In most species, AMPK exists as an obligate heterotrimer, containing a catalytic subunit (a), and two regulatory subunits (β and γ). AMPK is hypothesized to be activated by a two-pronged mechanism (for a full review, see8). Under lowered intracellular ATP levels, AMP or ADP can directly bind to the γ regulatory subunits, leading to a conformational change that protects the activating phosphorylation of AMPK9,10. Recent studies discovering that ADP can also bind the nucleotide binding pockets in the AMPK γ suggest it may be the physiological nucleotide for AMPK activation under a variety of cellular stresses18-11. In addition to nucleotide binding, phosphorylation of Thr172 in the activation loop of AMPK is required for its activation, and several groups have demonstrated that the serine/threonine kinase LKB1 directly mediates this event12-14. Interestingly, LKB1 is a tumor suppressor gene mutated in the inherited cancer disorder Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and in a significant fraction of lung and cervical cancers, suggesting that AMPK could play a role in tumor suppression15. Importantly, AMPK can also be phosphorylated on Thr172 in response to calcium flux, independently of LKB1, via CAMKK2 (CAMKKβ) kinase, which is the closest mammalian kinase to LKB1 by sequence homology16-19. Additional studies have suggested the MAPKKK family member TAK1/MAP3K7 may also phosphorylate Thr172 but the contexts in which TAK1 might regulate AMPK in vivo, and whether that involves LKB1 still requires further investigation20, 21.

In mammals, there are two genes encoding the AMPK α catalytic subunit (α1 and α2), two β genes (β1 and β2) and three γ subunit genes (γ1, γ2 and γ3)22. The expression of some of these isoforms is tissue restricted, and functional distinctions are reported for the two catalytic α subunits, particularly of AMP- and LKB1-responsiveness and nuclear localization of AMPKα2 compared to the α123. However, the α1 subunit has been shown to localize to the nucleus under some conditions24, and the myristoylation of the (β isoforms has been shown to be required for proper activation of AMPK and its localization to membranes25. Additional control via regulation of the localization of AMPK26-28 or LKB129, 30 remains an critical underexplored area for future research.

Genetic studies of tissue-specific deletion of LKB1 have revealed that LKB1 mediates the majority of AMPK activation in nearly every tissue type examined to date, though CAMKK2 appears to be particularly involved in AMPK activation in neurons and T cells31, 32. In addition to regulating AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 phosphorylation, LKB1 phosphorylates and activates another twelve kinases related to AMPK33. This family of kinases includes the MARKs (1-4), SIKs (1-3), BRSK/SADs (1-2) and NUAKs (1-2) sub-families of kinases34. Although only AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 are activated in response to energy stress, there is a significant amount of crosstalk and shared substrates between AMPK and the AMPK related kinases15.

Many types of cellular stresses can lead to AMPK activation. In addition to physiological AMP/ADP elevation from stresses such as low nutrients or prolonged exercise, AMPK can be activated in response to several pharmacological agents (see Figure 1). Metformin, the most widely prescribed Type 2 diabetes drug, has been shown to activate AMPK35 and to do so in an LKB1 dependent manner36. Metformin and other biguanides, such as the more potent analog phenformin37, are thought to activate AMPK by acting as mild inhibitors of Complex I of the respiratory chain, which leads to a drop of intracellular ATP levels38, 39. Another AMPK agonist, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-b-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR) is a cell-permeable precursor to ZMP, which mimics AMP, and binds to the AMPKγ subunits40. Interestingly, the chemotherapeutic pemetrexed, which is an inhibitor of thymidylate synthase, also inhibits aminoimidazolecarboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (AICART), the second folate-dependent enzyme of purine biosynthesis, resulting in increased intracellular ZMP and activation of AMPK, similar to AICAR treatment41. Finally, a number of naturally occurring compounds including Resveratrol, a polyphenol found in the skin of red grapes, have been shown to activate AMPK and yield similar beneficial effects on metabolic disease as AICAR and metformin42, 43. Resveratrol can rapidly activate AMPK via inhibition of the F1F0 mitochondrial ATPase38 and the original studies suggesting that resveratrol directly binds and activates sirtuins have come into question44, 45. Indeed, the activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol in cells and mice appears to require increased NAD+ levels by AMPK activity46, 47.

The AMPK signaling pathway

AMPK is activated when AMP and ADP levels in the cells rise due to variety of physiological stresses, as well as pharmacological inducers. LKB1 is the upstream kinase activating it in response to AMP increase, whereas CAMKK2 activates AMPK in response to calcium increase. Activated AMPK directly phosphorylates a number of subtrates to acutely impact metabolism and growth, as well as phosphorylating a number of transcriptional regulators that mediate long term metabolic reprogramming. Shown are all the best-established substrates to date-those needing further in vivo examination are italicized. Question marks denote candidate substrates whose identified phosphorylation sites diverge from the established optimal substrate motif (which all the others conform to). A full lineup of the identified AMPK phosphorylation sites in these substrates in Supplemental Table 1. Substrates in red have been reported to serve as substrates of other AMPK family members (SIK1, SIK2, MARKs, SADs) in vivo in addition to being substrates of AMPK.

The principle therapeutic mode of action of metformin in diabetes is via suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis7, 48, 49, though it remains controversial whether AMPK is absolutely required for the glucose lowering effects of metformin50. Since metformin acts as a mitochondrial inhibitor, it should be expected to activate a variety of stress sensing pathways which could redundantly serve to inhibit hepatic gluconeogenesis, of which currently AMPK is just one of the best appreciated. Critical for future studies will be defining the relative contribution of AMPK and other stress-sensing pathways impacted by metformin and the aforementioned energy stress agents in accurate in vivo models of metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance in which these agents show therapeutic benefit. Nonetheless, metformin, AICAR51, the direct small molecule AMPK activator A76966252, and genetic expression of activated AMPK in liver53 all lower blood glucose levels, leaving AMPK activation a primary goal for future diabetes therapeutics54. As a result of the diverse beneficial effects of this endogenous metabolic checkpoint in other pathological conditions, including several types of human cancer, there is an increasing interest in identifying novel AMPK agonists to be exploited for therapeutic benefits.

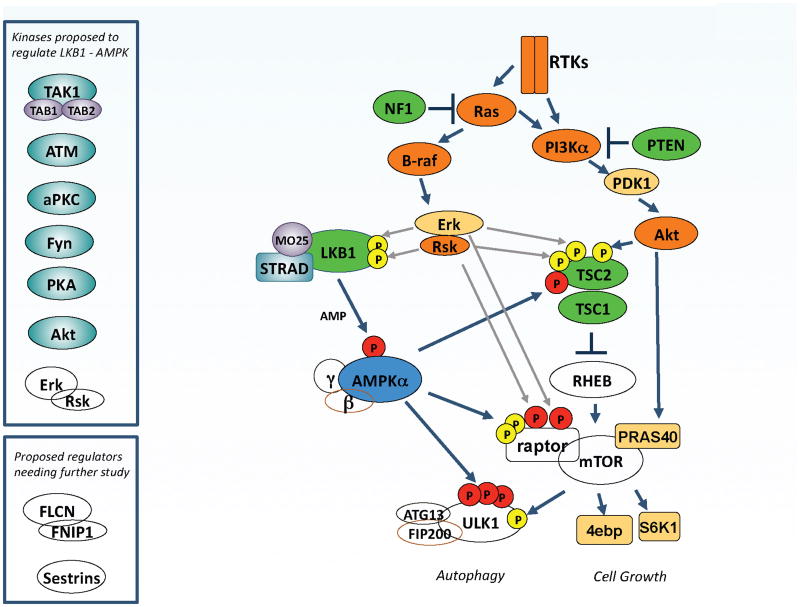

AMPK coordinates Control of Cell Growth and Autophagy

In conditions where nutrients are scarce, AMPK acts as a metabolic checkpoint inhibiting cellular growth. The most thoroughly described mechanism by which AMPK regulates cell growth is via suppression of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway. One mechanism by which AMPK controls the mTORC1 is by direct phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor TSC2 on serine 1387 (Ser1345 in rat TSC2). However, in lower eukaryotes, which lack TSC2 and in TSC2-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) AMPK activation still suppresses mTORC1 55, 56. This led to the discovery that AMPK also directly phosphorylates Raptor (regulatory associated protein of mTOR), on two conserved serines, which blocks the ability of the mTORC1 kinase complex to phosphorylate its substrates42.

In addition to regulating cell growth, mTORC1 also controls autophagy, a cellular process of “self engulfment” in which the cell breaks down its own organelles (macroautophagy) and cytosolic components (microautophagy) to ensure sufficient metabolites when nutrients run low. The core components of the autophagy pathway were first defined in genetic screens in budding yeast and the most upstream components of the pathway include the serine/threonine kinase Atg1 and its associated regulatory subunits Atg13 and Atg1757, 58. In budding yeast, the Atg1 complex is inhibited by the Tor-raptor (TORC1) complex59-61. The recent cloning of the mammalian orthologs of the Atg1 complex revealed that its activity is also suppressed by mTORC1 through a poorly defined mechanism likely to involve phosphorylation of the Atg1 homologs ULK1 and ULK2, as well as their regulatory subunits (reviewed in62). In contrast to inhibitory phosphorylations from mTORC1, studies from a number of laboratories in the past year have revealed that the ULK1 complex is activated via direct phosphorylation by AMPK, which is critical for its function in autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis (reviewed in63).

In addition to unbiased mass spectrometry studies discovering endogenous AMPK subunits as ULK1 interactors64, 65, two recent studies reported AMPK can directly phosphorylate several sites in ULK166, 67. Our laboratory found that hepatocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts devoid of either AMPK or ULK1 had defective mitophagy and elevated levels of p62 (Sequestrosome-1), a protein involved in aggregate turnover which itself is selectively degraded by autophagy66. As observed for other core autophagy proteins, ULK1 was required for cell survival following nutrient deprivation and this also requires the phosphorylation of the AMPK sites in ULK1. Similarly, genetic studies in budding yeast68 and in C. elegans66 demonstrate that Atg1 is needed for the effect of AMPK on autophagy. Interestingly, Kim and colleagues found distinct sites in ULK1 targeted by AMPK, though they also found that AMPK regulation of ULK1 was needed for ULK1 function67. These authors also mapped a direct mTOR phosphorylation site in ULK1 which appears to dictate AMPK binding to ULK1, a finding corroborated by another recent study, though the details differ69. Collectively, these studies show that AMPK can trigger autophagy in a double-pronged mechanism of directly activating ULK1 and inhibiting the suppressive effect of mTORC1 complex1 on ULK1 (see Fig. 2). Many of the temporal and spatial details of the regulation of these three ancient interlocking nutrient-sensitive kinases (AMPK, ULK1, mTOR) remains to be decoded.

The Ras/ PI3K/ mTOR pathways intersect the LKB1/AMPK pathway at multiple points

LKB1, the upstream kinase for AMPK, is the tumor suppressor gene mutated in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS), as well a significant fraction of sporadic lung cancers and cervical cancers. PJS patients share a number of clinical features with patients inheriting defective PTEN or TSC tumor suppressors, perhaps due to their control of common biochemical pathways, best understood currently being the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway. Extensive cross-regulation of the LKB1/AMPK pathway by the oncogenic Ras and PI3K pathways has been discovered, which may explain how these commonly mutated oncogenes also try to circumvent this endogenous tumor suppressor pathway. The ULK1/hATG1 kinase complex has emerged recently as a central node receiving inputs from both AMPK and mTORC1. A number of kinases that can phosphorylate specific residues in LKB1 or AMPK have been identified (upper inset), though the contexts in which most of these regulatory events occur is poorly defined at present, as is the functional impact of these phosphorylation events on AMPK signaling. The BHD tumor suppressor and its partner FNIP1, as well as the sestrin family of proteins, have also been implicated as being upstream or downstream of AMPK and mTOR depending on the context.

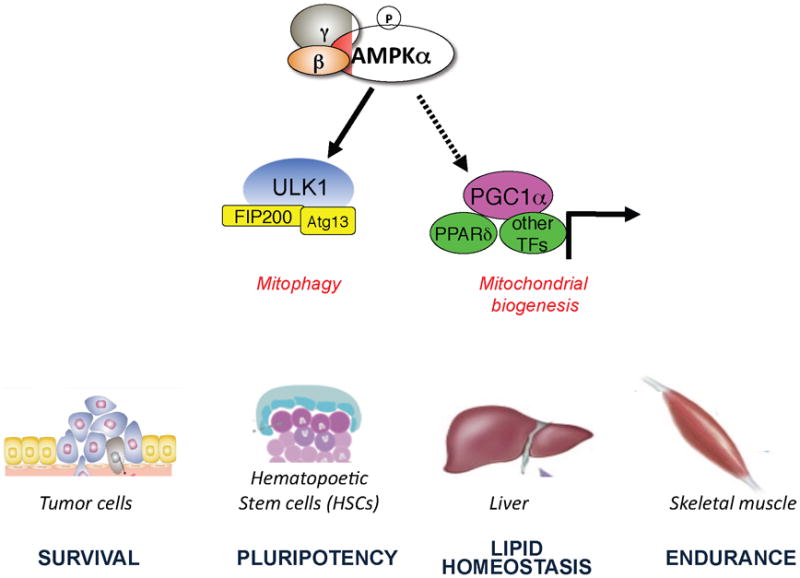

Interestingly, AMPK both triggers the acute destruction of defective mitochondria through a ULK1-dependent stimulation of mitophagy, as well as stimulating de novo mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α dependent transcription (see below). Thus AMPK controls mitochondrial homeostasis in a situation resembling “Cash for Clunkers” in which existing defective mitochondria are replaced by new fuel-efficient mitochondria (Fig. 3). One context where AMPK control of mitochondrial homeostasis may be particularly critical is in the context of adult stem cell populations. In a recent study on haematopoetic stem cells, genetic deletion of LKB1 or both of the AMPK catalytic subunits phenocopied fibroblasts lacking ULK1 or the AMPK sites in ULK1 in terms of the marked accumulation of defective mitochondria70.

AMPK acts as a mitochondrial “Cash for Clunkers”

Activated AMPK acutely triggers the destruction of existing defective mitochondria via ULK1-dependent mitophagy and simultaneously triggers the biogenesis of new mitochondria via effects on PGC-1a dependent transcription. These dual processes controlled by AMPK have the net effect of replacing existing defective mitochondria with new functional mitochondria. This two-pronged control of mitochondria homeostasis by AMPK will have a number of physiological and pathological conditions where it plays a critical role, and a few are illustrated here.

Beyond effects on mTOR and ULK1, two other reported targets of AMPK in growth control are the tumor suppressor p5371 and the CDK inhibitor p2772, 73, though the reported sites of phosphorylation do not conform well to the AMPK substrate sequence found in other substrates. The recent discovery of AMPK family members controlling phosphatases74 presents another mechanism by which AMPK might control phosphorylation of proteins, without being the kinase to directly phosphorylate the site.

Control of Metabolism via Transcription and Direct effects on Metabolic Enzymes

AMPK was originally defined as the upstream kinase for the critical metabolic enzymes Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1 & ACC2) and HMG-CoA reductase, which serve as the rate-limiting steps for fatty-acid and sterol synthesis in wide-variety of eukaryotes75, 76. In specialized tissues such as muscle and fat, AMPK regulates glucose uptake via effects on the RabGAP TBC1D1, which along with its homolog TBC1D4 (AS160), play key roles in GLUT4 trafficking following exercise and insulin77. In fat, AMPK also directly phosphorylates lipases, including both hormone sensitive lipase (HSL)78 and adipocyte triglyceride lipase (ATGL)79, an AMPK substrate also functionally conserved in C. elegans4. Interestingly, mammalian ATGL and its liberation of fatty acids has recently been shown to be important in rodent models of cancer-associated cachexia80. Whether AMPK is important in this context remains to be seen.

In addition to acutely regulation of these metabolic enzymes, AMPK is also involved in a adaptive reprogramming of metabolism through transcriptional changes. Breakthroughs in this area have come through distinct lines of investigation. AMPK has been reported to phosphorylate and regulate a number of transcription factors, coactivators, the acetyltransferase p300, a subfamily of histone deacetylases, and even histones themselves. In 2010, Bungard et al., reported that AMPK can target transcriptional regulation through phosphorylation of histone H2B on Serine3681. Cells expressing a mutant H2B S36A blunted the induction of stress genes upregulated by AMPK including p21 and cpt1c81, 82. In addition, AMPK was chromatin immunoprecipitated at the promoters of these genes making this one of the first studies to detect AMPK at specific chromatin loci in mammalian cells81. Notably, Serine36 in H2B does not conform well to the AMPK consensus83; further studies will reveal whether this substrate is an exception or whether this phosphorylation is indirectly controlled.

AMPK activation has also recently been linked to circadian clock regulation, which couples daily light and dark cycles to control of physiology in a wide variety of tissues through tightly coordinated transcriptional programs84. Several master transcription factors are involved in orchestrating this oscillating network. AMPK was shown to regulate the stability of the core clock component Cry1 though phosphorylation of Cry1 Ser71, which stimulates the direct binding of the Fbox protein Fbxl3 to Cry1, targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation24. Importantly, this is the first example of AMPK-dependent phosphorylation inducing protein turnover, although this is a common mechanism utilized by other kinases. One would expect additional substrates in which AMPK-phosphorylation triggers degradation will be discovered. Another study linked AMPK to the circadian clock via effects on Casein kinase85, though the precise mechanism requires further investigation. A recent genetic study in AMPK-deficient mice also indicates that AMPK modulates the circadian clock to different extents in different tissues86.

As the role of transcriptional programs in the physiology of metabolic tissues is well-studied, many connections between AMPK and transcriptional control have been found in these systems. Importantly, many of the transcriptional regulators phosphorylated by AMPK in metabolic tissues are expressed more ubiquitously than initially appreciated and may be playing more central roles tying metabolism to growth. One example that was recently discovered is the lipogenic transcriptional factor Srebp187. Srebp1 induces a gene program including targets ACC1 and FASN that stimulate fatty acid synthesis in cells. In addition to being a critical modulator of lipids in liver and other metabolic tissues, Srebp1 mediated control of lipogenesis is needed in all dividing cells as illustrated in a recent study identifying Srebp1 as a major cell growth regulator in Drosophila and mammalian cells88. AMPK was recently found to phosphorylate a conserved serine near the cleavage site within Srebp1, suppressing its activation87. This further illustrates the acute and prolonged nature of AMPK control of biology. AMPK acutely controls lipid metabolism via phosphorylation of ACC1 and ACC2, while mediating long-term adaptive effects via phosphorylation of Srebp1 and loss of expression of lipogenic enzymes. AMPK has also been suggested to phosphorylate the glucose-sensitive transcription factor ChREBP89 which dictates expression of an overlapping lipogenic gene signature with Srebp190. Adding an extra complexity here is the observation that phosphorylation of the histone acetyltransferase p300 by AMPK and its related kinases impacts the acetylation and activity of ChREBP as well91. Interestingly, like Srebp1, ChREBP has also been shown to be broadly expressed and involved in growth control in some tumor cell settings, at least in cell culture92.

Similarly, while best appreciated for roles in metabolic tissues, the CRTC family of transcriptional co-activators for CREB and its related family members may also play roles in epithelial cells and cancer93. Recent studies in C. elegans revealed that phosphorylation of the CRTC ortholog by AMPK is needed for AMPK to promote lifespan extension94, reinforcing the potentially broad biological functions of these coactivators. In addition to these highly conserved targets of AMPK and its related kinases, AMPK has also been reported to phosphorylate the nuclear receptors HNF4α (NR2A1)95 and TR4 (NR2C2)96, the coactivator PGC-1α97 and the zinc-finger protein AREBP (ZNF692)98, though development of phospho-specific antibodies and additional functional studies are needed to further define the functional roles of these events.

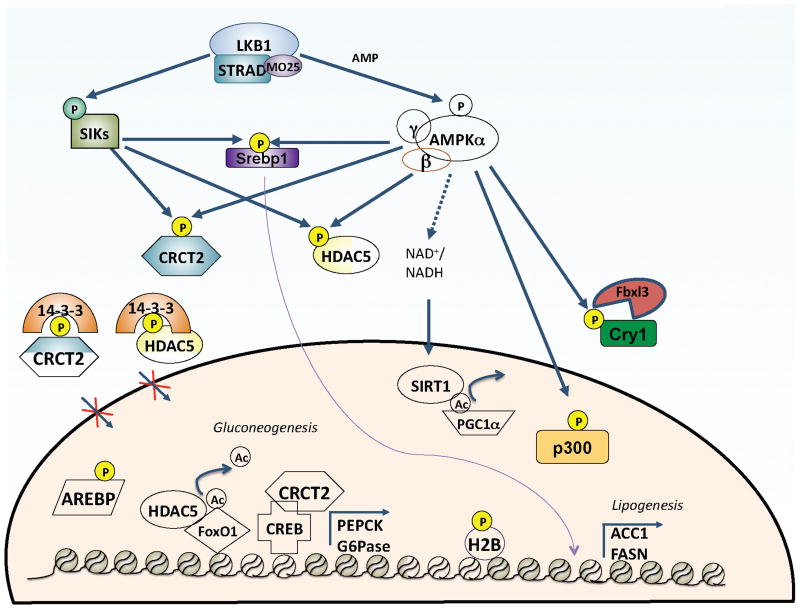

Another recently described set of transcriptional regulators targeted by AMPK and its related family members across a range of eukaryotes are the class IIa family of histone deacetylases (HDACs)99-105. In mammals the class IIa HDACs comprise a family of four functionally overlapping members: HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7, and HDAC9106 Like CRTCs, class IIa HDACs are inhibited by phosphorylation by AMPK and its family members, resulting in 14-3-3 binding and cytoplasmic sequestration. Recently, we discovered that similar to CRTCs, in liver the class IIa HDACs are dephosphorylated in response to the fasting hormone glucagon, resulting in transcriptional increases that are normally opposed by AMPK. Once nuclear, class IIa HDACs bind FOXO family transcription factors, stimulating their de-acetylation and activation,104 increasing expression of gluconeogenesis genes including G6Pase and PEPCK. Collectively, these findings suggest AMPK suppresses glucose production through two transcriptional effects: reduced expression of CREB targets via CRTC inactivation and reduced expression of FOXO target genes via class IIa HDAC inactivation (Figure 4). It is worth noting that while AMPK activation inhibits expression of FOXO gluconeogenic targets in the liver, in other cell types AMPK is reported to stimulate a set of FOXO-dependent target genes in stress resistance via direct phosphorylation of novel sites in FOXO3 and FOXO4 (though not FOXO1)107, an effect which appears conserved in C. elegans108. Ultimately, defining the tissues, isoforms, and conditions where the AMPK pathway controls FOXO via phosphorylation or acetylation is an important goal for understanding how these two ancient metabolic regulators are coordinated.

AMPK control of transcription

AMPK regulates several physiological processes through phosphorylation of transcription factors and co-activators. It shares substrates with its AMPK family related kinases to negatively regulate gluconeogenesis in the liver by phosphorylation and inhibition of the CRCT2 and Class IIa HDACs. These phosphorylation events induce binding to 14-3-3 scaffold proteins and sequestration of these transcription regulators into the cytoplasm. AMPK also regulates transcription factors via inducing their degradation (Cry1), preventing their proteolytic activation and translocation to nucleus (Srebp1), and by disrupting protein-protein (p300) or protein-DNA interactions (Arebp, HNF4a). AMPK has also been shown to directly control phosphorylation of Histone 2B on Serine 36 as well as indirectly controlling SIRT1 activity via increasing NAD+ levels.

In addition to phosphorylating transcription regulators, AMPK has also been shown to regulate the activity of the deacetylase SIRT1 in some tissues via effects on NAD+ levels109, 110. As SIRT1 targets a number of transcriptional regulators for deacetylation, this adds yet another layer of temporal and tissue specific control of metabolic transcription by AMPK. This has been studied best in the context of exercise and skeletal muscle physiology, where depletion of ATP activates AMPK and through SIRT1 promotes fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial gene expression. Interestingly, AMPK was also implicated in skeletal muscle reprogramming in a study where sedentary mice were treated with AICAR for 4 weeks and able to perform 44% better than control vehicle receiving counterparts111. This metabolic reprogramming was shown to require PPARβ/δ111 and likely involves PGC-1α as well97, though the AMPK substrates critical in this process have not yet been rigorously defined. Interestingly, the only other single agent ever reported to have such endurance reprogramming properties besides AICAR is Resveratrol112, whose action in regulating metabolism is now known to be critical dependent on AMPK47.

Control of Cell Polarity, Migration, & Cytoskeletal Dynamics

In addition to the ample data for AMPK in cell growth and metabolism, recent studies suggest that AMPK may control cell polarity and cytoskeletal dynamics in some settings113. It has been known for some time that LKB1 plays a critical role in cell polarity from simpler to complex eukaryotes. In C. elegans114 and Drosophila115, LKB1 orthologs establish cellular polarity during critical asymmetric cell divisions and in mammalian cell culture, activation of LKB1 was sufficient to promote polarization of certain epithelial cell lines116. Initially, it was assumed that the AMPK-related MARKs (Microtubule Affinity Regulating Kinases), which are homologs of C. elegans par-1 and play well-established roles in polarity, were the principal targets of LKB1 in polarity117. However, recent studies also support a role for AMPK in cell polarity.

In Drosophila, loss of AMPK results in altered polarity118, 119 and in mammalian MDCK cells, AMPK was activated and needed for proper re-polarization and tight junction formation following calcium switch120, 121. Moreover, LKB1 was shown to localize to adherens junctions in MDCK cells and E-cadherin RNAi led to specific loss of this localization and AMPK activation at these sites30. The adherens junctions protein Afadin122 and a Golgi-specific nucleotide exchange factor for Arf5 (GBF1)123 have been reported to be regulated by AMPK and may be involved in this polarity122, though more studies are needed to define these events and their functional consequences. In Drosophila AMPK deficiency altered multiple polarity markers, including loss of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation118. While it was suggested in this paper that MLC may be a direct substrate of AMPK, this seems unlikely as the sites do not conform to the optimal AMPK substrate motif. However, AMPK and its related family members have been reported to modulate the activity of kinases and phosphatases that regulate MLC (MLCK, MYPT1), so MLC phosphorylation may be indirectly controlled via one of these potential mechanisms.

Another recent study discovered the microtubule plus end protein CLIP-170 (CLIP1) as a direct AMPK substrate124. Mutation of the AMPK site in CLIP-170 caused slower microtubule assembly, suggesting a role in the dynamic of CLIP-170 dissociation from the growing end of microtubules. It is noteworthy that mTORC1 was also previously suggested as a kinase for CLIP-170125, introducing the possibility that like ULK1, CLIP-170 may be a convergence point in the cell for AMPK and mTOR signaling. Consistent with this, besides effects on cell growth, LKB1/AMPK control of mTOR was recently reported to control cilia126 and neuronal polarization under conditions of energy stress127. In addition, the regulation of CLIP-170 by AMPK is reminiscent of the regulation of MAPs (microtubule associated proteins) by the AMPK related MARK kinases, which are critical in Tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer's models128, 129. Indeed AMPK itself has been shown to target the same sites in Tau under some conditions as well130.

Finally, an independent study suggested a role for AMPK in polarizing neurons via control of PI3K localization131. Here, AMPK was shown to directly phosphorylate Kinesin Light Chain 2 (KLC2) and inhibit axonal growth via preventing PI3K localization to the axonal tip. Interestingly, a previous study examined the related protein KLC1 as a target of AMPK and determined it was not a real substrate in vivo132. Further experiments are needed to clarify whether AMPK is a bona fide kinase for KLC1 or KLC2 in vivo and in which tissues.

Emerging themes and future directions

An explosion of studies in the past 5 years has begun decoding substrates of AMPK playing roles in a variety of growth, metabolism, autophagy, and cell polarity processes. An emergent theme in the field is that AMPK and its related family members often redundantly phosphorylate a common set of substrates on the same residues, though the tissue expression and condition under which AMPK or its related family members are active vary. For example, CRTCs, Class IIa HDACs, p300, Srebp1, IRS1, and tau are reported to be regulated by AMPK and/or its SIK and MARK family members depending on the cell type or conditions. As a example of the complexity to be expected, SIK1 itself is transcriptionally regulated and its kinase activity is modulated by Akt and PKA so the conditions under which it is expressed and active will be a narrow range in specific cell types only, and usually distinct from conditions where AMPK is active. Delineating the tissues and conditions in which the 12 AMPK related kinases are active remains a critical goal for dissecting the growth and metabolic roles of their shared downstream substrates. A much more comprehensive analysis of AMPK and its family members using genetic loss of function and RNAi is needed to decode the relative importance of each AMPK family kinase on a given substrate for each cell type.

Now with a more complete list of AMPK substrates, it is also becoming clear that there is a convergence of AMPK signaling with PI3K and Erk signaling in growth control pathways, and with insulin and cAMP-dependent pathways in metabolic control. The convergence of these pathways reinforces the concept that there is a small core of rate-limiting regulators that control distinct aspects of biology and act as master coordinators of cell growth, metabolism, and ultimately cell fate. As more targets of AMPK are decoded, the challenge will be in defining more precisely which targets are essential and relevant for the beneficial effects of AMPK activation seen in pathological states ranging from diabetes to cancer to neurological disorders. The identification of these downstream effectors will provide new targets for therapeutically treating these diseases by unlocking this endogenous mechanism that evolution has developed to restore cellular and organismal homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

SupplInfo

Click here to view.(68K, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The authors want to apologize for the many primary studies in the AMPK field that could be not covered due to space limitations. Work in the authors' laboratory is, or has been, funded by the NIH grants R01 DK080425 and 1P01CA120964, an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award, the American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist Award. We also thank the Adler Family Foundation and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust for their generous support.

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests.

References

1. Baena-Gonzalez E, Rolland F, Thevelein JM, Sheen J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature. 2007;448:938–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Hedbacker K, Carlson M. SNF1/AMPK pathways in yeast. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2408–2420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bokko PB, et al. Diverse cytopathologies in mitochondrial disease are caused by AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1874–1886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Narbonne P, Roy R. Caenorhabditis elegans dauers need LKB1/AMPK to ration lipid reserves and ensure long-term survival. Nature. 2009;457:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Johnson EC, et al. Altered metabolism and persistent starvation behaviors caused by reduced AMPK function in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2010;5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Thelander M, Olsson T, Ronne H. Snf1-related protein kinase 1 is needed for growth in a normal day-night light cycle. Embo J. 2004;23:1900–1910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Hardie DG, Carling D, Gamblin SJ. AMP-activated protein kinase: also regulated by ADP? Trends Biochem Sci. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Xiao B, et al. Structure of mammalian AMPK and its regulation by ADP. Nature. 2011;472:230–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Oakhill JS, et al. AMPK is a direct adenylate charge-regulated protein kinase. Science. 2011;332:1433–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Bland ML, Birnbaum MJ. Cell biology. ADaPting to energetic stress. Science. 2011;332:1387–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Hawley SA, et al. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRADalpha/beta and MO25alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Woods A, et al. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2004–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]