The toxic truth about sugar

- Comment

- Published: 01 February 2012

Public health

The toxic truth about sugar

Nature volume 482, pages27–29 (2012)Cite this article

Added sweeteners pose dangers to health that justify controlling them like alcohol, argue Robert H. Lustig, Laura A. Schmidt and Claire D. Brindis.

SUMMARY

Last September, the United Nations declared that, for the first time in human history, chronic non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes pose a greater health burden worldwide than do infectious diseases, contributing to 35 million deaths annually.

This is not just a problem of the developed world. Every country that has adopted the Western diet — one dominated by low-cost, highly processed food — has witnessed rising rates of obesity and related diseases. There are now 30% more people who are obese than who are undernourished. Economic development means that the populations of low- and middle-income countries are living longer, and therefore are more susceptible to non-communicable diseases; 80% of deaths attributable to them occur in these countries.

설탕 섭취는 비전염성 질병의 증가와 관련이 있습니다.

설탕이 신체에 미치는 영향은 알코올과 비슷할 수 있습니다.

세금 부과, 수업 시간 판매 제한, 구매 연령 제한 등의 규제가 포함될 수 있습니다.

지난 9월,

유엔은 인류 역사상 처음으로

심장병, 암, 당뇨병과 같은 만성 비전염성 질환이

전염병보다 전 세계적으로 더 큰 건강 부담을 초래하여

연간 3,500만 명이 사망한다고 선언했습니다.

이는 비단 선진국만의 문제가 아닙니다.

저가의 고도로 가공된 식품이 주를 이루는 서구식 식단을 채택한 모든 국가에서

비만 및 관련 질병의 발병률이 증가하고 있습니다.

현재 영양 결핍인 사람보다

비만인 사람이 30% 더 많습니다.

경제 발전으로 인해 저소득 및 중간 소득 국가의 인구가 더 오래 살면서 비전염성 질병에 더 취약해졌고, 이로 인한 사망의 80%가 이들 국가에서 발생하고 있습니다.

Credit: ILLUSTRATION BY MARK SMITH

Many people think that obesity is the root cause of these diseases. But 20% of obese people have normal metabolism and will have a normal lifespan. Conversely, up to 40% of normal-weight people develop the diseases that constitute the metabolic syndrome: diabetes, hypertension, lipid problems, cardiovascular disease andnon-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity is not the cause; rather, it is a marker for metabolic dysfunction, which is even more prevalent.

The UN announcement targets tobacco, alcohol and diet as the central risk factors in non-communicable disease. Two of these three — tobacco and alcohol — are regulated by governments to protect public health, leaving one of the primary culprits behind this worldwide health crisis unchecked. Of course, regulating food is more complicated — food is required, whereas tobacco and alcohol are non-essential consumables. The key question is: what aspects of the Western diet should be the focus of intervention?

In October 2011, Denmark chose to tax foods high in saturated fat, despite the fact that most medical professionals no longer believe that fat is the primary culprit. But now, the country is considering taxing sugar as well — a more plausible and defensible step. Indeed, rather than focusing on fat and salt — the current dietary 'bogeymen' of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the European Food Safety Authority — we believe that attention should be turned to 'added sugar', defined as any sweetener containing the molecule fructose that is added to food in processing.

Over the past 50 years, consumption of sugar has tripled worldwide. In the United States, there is fierce controversy over the pervasive use of one particular added sugar — high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). It is manufactured from corn syrup (glucose), processed to yield a roughly equal mixture of glucose and fructose. Most other developed countries eschew HFCS, relying on naturally occurring sucrose as an added sugar, which also consists of equal parts glucose and fructose.

Authorities consider sugar as 'empty calories' — but there is nothing empty about these calories. A growing body of scientific evidence is showing that fructose can trigger processes that lead to liver toxicity and a host of other chronic diseases1. A little is not a problem, but a lot kills — slowly (see 'Deadly effect'). If international bodies are truly concerned about public health, they must consider limiting fructose — and its main delivery vehicles, the added sugars HFCS and sucrose — which pose dangers to individuals and to society as a whole.

많은 사람이 비만이 이러한 질병의 근본 원인이라고 생각합니다. 하지만 비만인 사람의 20%는 신진대사가 정상이며 정상적인 수명을 유지합니다. 반대로 정상 체중인 사람의 최대 40%는 당뇨병, 고혈압, 지질 문제, 심혈관 질환 및비알코올성 지방간 질환과 같은 대사 증후군을 구성하는 질병에 걸립니다. 비만은 원인이 아니라 대사 기능 장애의 지표이며, 이는 훨씬 더 널리 퍼져 있습니다.

유엔의 발표는 담배, 알코올, 식습관을 비감염성 질환의 주요 위험 요인으로 지목했습니다. 이 세 가지 중 담배와 술은 공중 보건을 보호하기 위해 각국 정부가 규제하고 있지만, 전 세계 건강 위기의 주범 중 하나인 음식은 방치되고 있습니다. 물론 식품은 필수품인 반면 담배와 술은 비필수 소비재이기 때문에 식품에 대한 규제는 더 복잡합니다. 핵심 질문은 서구식 식단의 어떤 측면에 개입의 초점을 맞춰야 하는가 하는 것입니다.

2011년 10월, 덴마크는 대부분의 의료 전문가들이 더 이상 지방이 주범이라고 믿지 않음에도 불구하고 포화 지방이 많은 식품에 세금을 부과하기로 결정했습니다. 하지만 이제 덴마크는 설탕에도 세금을 부과하는 것을 고려하고 있습니다. 이는 더 그럴듯하고 방어 가능한 조치입니다.

실제로 현재 미국 농무부(USDA)와 유럽 식품안전청의 식단

'악당'인 지방과 소금에 초점을 맞추기보다는

가공 과정에서 식품에 첨가되는

과당 분자를 함유한 감미료로 정의되는

첨가당'에 관심을 기울여야 한다고 믿습니다.

지난 50년 동안 설탕 소비량은 전 세계적으로 3배나 증가했습니다. 미국에서는 특정 첨가당인 고과당 옥수수 시럽(HFCS)의 광범위한 사용에 대해 치열한 논쟁이 벌어지고 있습니다. 이 설탕은 옥수수 시럽(포도당)으로 제조되며 포도당과 과당이 거의 같은 비율로 혼합되도록 가공됩니다. 대부분의 다른 선진국에서는 HFCS를 사용하지 않고 포도당과 과당이 같은 비율로 함유된 자연 발생 자당을 첨가당으로 사용합니다.

당국은 설탕을 '빈 칼로리'로 간주하지만, 이 칼로리에는 빈 것이 없습니다. 과당이 간 독성 및 기타 여러 만성 질환으로 이어지는 과정을 유발할 수 있다는 과학적 증거가 점점 더 많이 나오고 있습니다1. 소량은 문제가 되지 않지만 많은 양을 섭취하면 서서히 사망에 이르게 됩니다('치명적인 영향' 참조). 국제기구가 진정으로 공중 보건을 염려한다면 개인과 사회 전체에 위험을 초래하는 과당과 과당의 주요 전달 수단인 첨가당 HFCS 및 자당을 제한하는 것을 고려해야 합니다.

Table 1 Deadly effect Excessive consumption of fructose can cause many of the same health problems as alcohol.

No ordinary commodity

In 2003, social psychologist Thomas Babor and his colleagues published a landmark book called Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity, in which they established four criteria, now largely accepted by the public-health community, that justify the regulation of alcohol — unavoidability (or pervasiveness throughout society), toxicity, potential for abuse and negative impact on society2. Sugar meets the same criteria, and we believe that it similarly warrants some form of societal intervention.

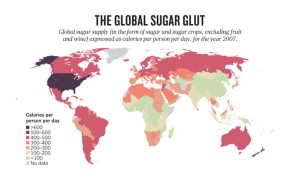

First, consider unavoidability. Evolutionarily, sugar was available to our ancestors as fruit for only a few months a year (at harvest time), or as honey, which was guarded by bees. But in recent years, sugar has been added to nearly all processed foods, limiting consumer choice3. Nature made sugar hard to get; man made it easy. In many parts of the world, people are consuming an average of more than 500 calories per day from added sugar alone (see 'The global sugar glut').

Credit: SOURCE: FAO

Now, let's consider toxicity. A growing body of epidemiological and mechanistic evidence argues that excessive sugar consumption affects human health beyond simply adding calories4. Importantly, sugar induces all of the diseases associated with metabolic syndrome1,5. This includes: hypertension (fructose increases uric acid, which raises blood pressure); high triglycerides and insulin resistance through synthesis of fat in the liver; diabetes from increased liver glucose production combined with insulin resistance; and the ageing process, caused by damage to lipids, proteins and DNA through non-enzymatic binding of fructose to these molecules. It can also be argued that fructose exerts toxic effects on the liver that are similar to those of alcohol1. This is no surprise, because alcohol is derived from the fermentation of sugar. Some early studies have also linked sugar consumption to human cancer and cognitive decline.

Sugar also has clear potential for abuse. Like tobacco and alcohol, it acts on the brain to encourage subsequent intake. There are now numerous studies examining the dependence-producing properties of sugar in humans6. Specifically, sugar dampens the suppression of the hormone ghrelin, which signals hunger to the brain. It also interferes with the normal transport and signalling of the hormone leptin, which helps to produce the feeling of satiety. And it reduces dopamine signalling in the brain's reward centre, thereby decreasing the pleasure derived from food and compelling the individual to consume more1,6.

Finally, consider the negative effects of sugar on society. Passive smoking and drink-driving fatalities provided strong arguments for tobacco and alcohol control, respectively. The long-term economic, health-care and human costs of metabolic syndrome place sugar overconsumption in the same category7. The United States spends $65 billion in lost productivity and $150 billion on health-care resources annually for morbidities associated with metabolic syndrome. Seventy-five per cent of all US health-care dollars are now spent on treating these diseases and their resultant disabilities. Because about 25% of military applicants are now rejected for obesity-related reasons, the past three US surgeons general and the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff have declared obesity a “threat to national security”.

How to intervene

How can we reduce sugar consumption? After all, sugar is natural. Sugar is a nutrient. Sugar is pleasure. So too is alcohol, but in both cases, too much of a good thing is toxic. It may be helpful to look to the many generations of international experience with alcohol and tobacco to find models that work8,9. So far, evidence shows that individually focused approaches, such as school-based interventions that teach children about diet and exercise, demonstrate little efficacy. Conversely, for both alcohol and tobacco, there is robust evidence that gentle 'supply side' control strategies which stop far short of all-out prohibition — taxation, distribution controls, age limits — lower both consumption of the product and the accompanying health harms. Successful interventions share a common end-point: curbing availability2,8,9.

Taxing alcohol and tobacco products — in the form of special excise duties, value-added taxes and sales taxes — are the most popular and effective ways to reduce smoking and drinking, and in turn, substance abuse and related harms2. Consequently, we propose adding taxes to processed foods that contain any form of added sugars. This would include sweetened fizzy drinks (soda), other sugar-sweetened beverages (for example, juice, sports drinks and chocolate milk) and sugared cereal. Already, Canada and some European countries impose small additional taxes on some sweetened foods. The United States is currently considering a penny-per-ounce soda tax (about 34 cents per litre), which would raise the price of a can by 10–12 cents. Currently, a US citizen consumes an average of 216 litres of soda per year, of which 58% contains sugar. Taxing at a penny an ounce could provide annual revenue in excess of $45 per capita (roughly $14 billion per year); however, this would be unlikely to reduce total consumption. Statistical modelling suggests that the price would have to double to significantly reduce soda consumption — so a $1 can should cost $2 (ref. 10).

Other successful tobacco- and alcohol-control strategies limit availability, such as reducing the hours that retailers are open, controlling the location and density of retail markets and limiting who can legally purchase the products2,9. A reasonable parallel for sugar would tighten licensing requirements on vending machines and snack bars that sell sugary products in schools and workplaces. Many schools have removed unhealthy fizzy drinks and candy from vending machines, but often replaced them with juice and sports drinks, which also contain added sugar. States could apply zoning ordinances to control the number of fast-food outlets and convenience stores in low-income communities, and especially around schools, while providing incentives for the establishment of grocery stores and farmer's markets.

Another option would be to limit sales during school operation, or to designate an age limit (such as 17) for the purchase of drinks with added sugar, particularly soda. Indeed, parents in South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, recently took this upon themselves by lining up outside convenience stores and blocking children from entering them after school. Why couldn't a public-health directive do the same?

The possible dream

Government-imposed regulations on the marketing of alcohol to young people have been quite effective, but there is no such approach to sugar-laden products. Even so, the city of San Francisco, California, recently banned the inclusion of toys with unhealthy meals such as some types of fast food. A limit — or, ideally, ban — on television commercials for products with added sugars could further protect children's health.

Reduced fructose consumption could also be fostered through changes in subsidization. Promotion of healthy foods in US low-income programmes, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (also known as the food-stamps programme) is an obvious place to start. Unfortunately, the petition by New York City to remove soft drinks from the food-stamp programme was denied by the USDA.

Ultimately, food producers and distributors must reduce the amount of sugar added to foods. But sugar is cheap, sugar tastes good and sugar sells, so companies have little incentive to change. Although one institution alone can't turn this juggernaut around, the US Food and Drug Administration could “set the table” for change8. To start, it should consider removing fructose from the Generally Regarded as Safe (GRAS) list, which allows food manufacturers to add unlimited amounts to any food. Opponents will argue that other nutrients on the GRAS list, such as iron and vitamins A and D, can also be toxic when over-consumed. However, unlike sugar, these substances have no abuse potential. Removal from the GRAS list would send a powerful signal to the European Food Safety Authority and the rest of the world.

Regulating sugar will not be easy — particularly in the 'emerging markets' of developing countries where soft drinks are often cheaper than potable water or milk. We recognize that societal intervention to reduce the supply and demand for sugar faces an uphill political battle against a powerful sugar lobby, and will require active engagement from all stakeholders. Still, the food industry knows that it has a problem — even vigorous lobbying by fast-food companies couldn't defeat the toy ban in San Francisco. With enough clamour for change, tectonic shifts in policy become possible. Take, for instance, bans on smoking in public places and the use of designated drivers, not to mention airbags in cars and condom dispensers in public bathrooms. These simple measures — which have all been on the battleground of American politics — are now taken for granted as essential tools for our public health and well-being. It's time to turn our attention to sugar.

References

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert H. Lustig.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lustig, R., Schmidt, L. & Brindis, C. The toxic truth about sugar. Nature 482, 27–29 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/482027a