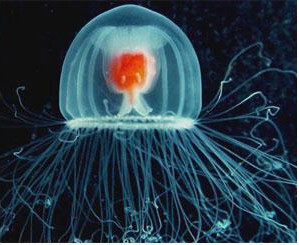

홍해파리

Immortal jellyfish

이명 : 작은 보호탑 해파리

The so-called ‘immortal’ jellyfish, or Turritopsis dohrnii, can somehow reprogramme the identity of its own cells, returning it to an earlier stage of life. In other words, it can age in reverse and morph from an adult back into a baby.

영원히 죽지않는 단 하나의 생명체 : 영생불사 해파리

인류의 오랜 소원 중 하나인 영원한 삶, 과학기술이 발달하면서 평균수명 100세 시대가 열렸지만 영원한 삶은 여전히 꿈만 같은 이야기이다. 모든 생명체는 태어남과 동시에 죽음으로 향한 레이스를 시작한다.

하지만 영생불사라는 꿈만같은 삶을 살고있는 단 하나의 생명체가 있었으니 바로 최근에 언론에 보도된 일명 '영생불사 해파리'이다.

학명 : 투리토프시스 누트리큘라Turritopsis nutricula

1990년대 이탈리아에서 처음 발견된 해파리의 일종인 몸길이 5mm 남짓의 투리토프시스 누트리큘라는 병들거나 잡아먹히지 않는 한 이론적으로 영생불사 할 수 있는 유일한 생명체이다.

영생불사 해파리의 라이프 사이클(왼쪽)과 폴립형태(오른쪽)

죽지않고 다시 어린시절로

대부분의 해파리는 번식 후 죽음을 맞는데 그 수명은 체 1년이 안된다. 그러나 영생불사 해파리는 번식 후 또는 외부 환경이 좋지않아 영양분이 없을때 우산 모양의 몸이 뒤집히고 촉수와 바깥쪽 세포들이 몸 안으로 흡수되면서 세포덩어리로 돌아간다 그리고는 아래로 가라앉아 바위에 부착되면 고착형 폴립(미성숙 단계)이 된다.

불사(不死)는 맞지만 불로(不老)는 아니다

이 영생불사 해파리도 영원히 젊은 상태를 유지하는 것은 아니다, 노쇠하여 수명이 다하기 직전에 다시 젊은 상태로 회귀하는 라이프 사이클을 계속 반복한다.

전세계로 퍼져나가는 영생불사 해파리

과학자들은 영생불사 해파리가 본래 서식지인 열대 해역은 물론 전 세계 바다로 급속히 퍼져나고있을 것으로 추정했다.

밸러스트 워터, 즉 화물선이 균형을 잡기 위해 출항지 항만에서 싣고 목적지에서 쏟아내는 물이 영생불사 해파리의 전파를 가능하게 했을 것이라고 한다. 영생불사 해파리는 우리나라에서도 서식하고 있는것으로 확인되었으며, 우리말로 '작은보호탑 해파리'라 불리며 학회에 정식 보고도 되었다.

영생불사 해파리의 성체

노쇠하고 다시 어린시절로 돌아가는 그 과정을 몇번이나 반복했을지 짐작하기 힘들다.

어쩌면 이들 중 운이 좋은 녀석은 지구 역사의 오랫동안을 함께했을 것이다.

오늘도 영상불사 해파리는 바다 깊은 곳에서, 생명연장에 매진하고있는 인간을 비웃고 있을지도 모른다.

https://www.bbcearth.com/blog/?article=the-animal-that-lives-forever

The animal that lives forever

By Chris Baraniuk

In the warm seas of the Mediterranean lives a jellyfish with an extraordinarily rare ability – it can rewind its life cycle.

The so-called ‘immortal’ jellyfish, or Turritopsis dohrnii, can somehow reprogramme the identity of its own cells, returning it to an earlier stage of life. In other words, it can age in reverse and morph from an adult back into a baby.

In the science fiction television series Doctor Who, the programme’s hero periodically transforms into a completely new version of himself. Like Turritopsis dohrnii, the Doctor sometimes does this when he has been badly wounded or would otherwise die.

For the jellyfish, its ability to become a younger version of itself is a spectacular survival mechanism that plays out when it gets old or sick or faces danger. Once the reversal process has been initiated, the jellyfish’s bell and tentacles deteriorate and it turns back into a polyp – a plant-like structure that attaches itself to a surface underwater. It does this partly through a process known as cellular transdifferentiation – when cells change from one type directly into another, producing an entirely new body plan. And it can do it again and again.

A team of researchers recently sequenced a small part of the jellyfish’s DNA. Professor Stefano Piraino at the University of Salento in Italy was involved in the work and is now coordinating a project called PHENIX to better understand the communication between cells in Turritopsis dohrnii. He says the secret of ‘life reversal’ might only be found after the creature’s full genome has been unravelled.

Immortal Jellyfish

Professor Piraino also notes that the death of the jellyfish has been observed in the lab – perhaps disappointingly, it’s not truly ‘immortal’ after all.

Still, the adaptation remains remarkable and two other jellyfish have recently been discovered to have it, including Aurelia sp.1, native to the East China Sea.

A new lease on life

If humans could somehow tap into the transdifferentiation process, could we regenerate? To some extent we already do – scars, bruises and healing after sunburn are all signs of our skin regenerating. We can regrow the tips of our fingers and toes, too.

It was once a popular idea that we become a new person every seven to 10 years as, in that time, all the cells in our body will have died and been replaced. While this myth has been busted, it is true that our cells are continually dying and being replaced.

But as a Time Lord, the Doctor goes through a far more complete transformation process. However, regeneration like his does happen in other animals, though it’s usually limited to just portions of the body. Take salamanders, for instance.

“They are considered the champions of regeneration,” says Dr Maximina Yun at University College London.

“Some can regenerate parts of their hearts, their jaws, whole legs and arms – and the tail including the spinal cord.”

The precise mechanism through which salamanders achieve this is not known, but Dr Yun has been experimenting with blastemas – clumps of cells that form when regeneration of a lost body part is triggered at the site of an amputation in salamanders.

She and her colleagues recently found evidence suggesting that salamanders suppress a certain protein, p53, which may contribute to cells taking on a new identity. This would allow cells to develop into the necessary muscle, nerves and bone tissue for a regenerated leg, for example.

It’s hoped that humans may ultimately be able to harness this process for our own benefit (for more on this, see ‘Doctoring ourselves’ on the previous page).

Dr Yun’s team is also investigating the role of the immune system. Once thought to be a potential hindrance to regeneration, she says the presence of immune system cells, macrophages, has now been shown to be ‘essential’ for regeneration. ‘It’s possible that this is the key element,’ she adds.

It’s worth noting that various types of salamander have different means of regenerating. Axolotls, for instance, can trigger the production of stem cells – which can develop into any type of cell – where regeneration is wanted. But newts, when regenerating muscle tissue, use a process called dedifferentiation, in which a specific cell is encouraged to proliferate.

Looking the part

When the Doctor regenerates, he becomes an entirely new person, with a different form and appearance, and perhaps even a different gender. Animals that are able to drastically change their appearance at a moment’s notice are fairly rare, but new examples are being discovered all the time.

Only two years ago, researchers in the Ecuadorian rainforest realised that a certain species of frog, Pristimantis mutabilis, could suddenly change the texture of its skin from rough and spiky to completely smooth in a matter of just a few minutes.

The frog had been known to science for nearly a decade, but this shape-shifting ability – thought to help the frog blend into its environment – had never been documented before.

“It happens so quickly, I think the behaviour just hadn’t been noticed before,” explains Dr Louise Gentle from Nottingham Trent University. “It had been fooling everyone.”

Other animals have long been known to use similar camouflaging tricks, including many species of octopus that can suddenly transform the texture and colour of their bodies to match the surface on which they are resting. It’s not known how this response is triggered. It may be similar to goosebumps on human skin – an involuntary reaction triggered by, for example, low temperatures, explains Dr Gentle.

“But it might be they are recognising their background and consciously making that decision [to transform],” she adds.

Of course, some organisms take on entirely new forms through metamorphosis – the most well-known example being the many caterpillars that form a chrysalis and later emerge as butterflies. But there are some surprising other examples, too. Various species of single-celled amoeba frequently join together as multicellular structures – in other words, they team up to transform. For example, one species, Dictyostelium discoideum, has been found to clump together to form a ‘slug’ when it needs to find food. When the slug has settled on a new feeding ground, it changes form again, into a mature fruiting body that releases spores and begins the life cycle over again.

As more of these examples come to light, Dr Yun observes, “Science is slowly catching up with science fiction.”