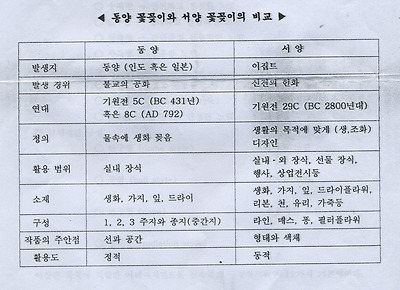

굳이 박물관 까지 찾아가지 않더라도 웬만한 가정에서는 동양화 한점쯤은 볼 수가 있으리라 생각합니다.

그런데 서양화를 배우고 서양화에 익숙해 있는 우리의 시각으로 보면 동양화는 이해가 안되는 부분이 많습니다.

그 첫째가, 우리가 학교에서 미술(회화)를 배울때는 빈 공간 없이 크레파스로 짙게 칠을 잘 해야 잘 그렸다고 칭찬을 받았었는데, 동양화는 하얀 여백이 절반 이상의 공간을 차지하고 있어서 미완성의 그림으로 보이게 됩니다.

두번째는, 먼 경치는 작게 그리고 가까운 것은 크게그려야 원근법에 맞는데 동양화에서는 이와 같은 원근법이 없습니다.

세번째는, 요즘 말로 풍경화라 할 수 있는 진경산수화를 보면 실제 현장에서 보이는 경치와는 다른 모양으로 그려져 있습니다. 쉬운 예로 겸제선생의 금강산전도는 금강산 일만이천봉을 한장의 그림에 그렸는데 이 세상 어느 지점에서 보아도 그와 같은 경치는 보이지 않는다는 것입니다.

이상의 문제에 대하여 정리해 보고자 합니다.

첫째, 여백의 문제인데, 서양화에서는 여백은 미완성으로 보지만 동양화에서는 여백을 이용하여 구도를 잡는다는 것입니다. 그래서 동양화는 여백의 미를 극대화한 미술이라 합니다.

두번째, 원근법의 문제인데 미술에서 원근을 표현하는 방법은 여러가지가 있다는 것입니다. 서양화에서는 크기로 표현하는데 반하여 동양화에서는 먼 것은 흐리게 그리고 가까운 것은 짙게그리는 방법과, 가까운 것은 화폭의 아래에 그리고 먼 것은 화폭의 위에 그리는 방법(산에 올라가서 먼 경치를 본다고 상상해 보십시요)을 사용한다는 것입니다. 따라서 원근법은 표현기법의 차이가 있을 뿐 동양화에 원근법이 없다는 말은 옳지 않습니다(참고로 우리나라에 서양식 원근법의 도입은 조선 정조 때 부터입니다)

셋째, 사실과 다르다는 경치의 문제는, 서양화는 그림을 그릴 때 한곳에 이젤을 세우고 그 자리에서 보이는 경치를 그대로 그립니다. 다시 말하면 그림을 바라보는 시점이 한 곳에 고정되어 있다는 말 입니다. 그래서 서양화를 감상할 때는 액자에 넣어서 벽에 걸어두고 보는 것입니다.

반면에 동양화는 이동시점을 사용합니다. 금강산 전도를 그린다면 금강산을 전체를 돌아보면서 부분 부분을 스케치한 후 이것들을 모아서 한장의 그림으로 그린다는 것입니다. 이해를 돕기 위하여 하나를 더 예로 든다면, 조선초 안평대군의 꿈을 안견이 그렸다는 몽유도원도를 들 수 있는데, 옆으로 긴 그림입니다. 안평대군이 꿈에 무릉도원을 찾아가서 놀았다는 이야기를 한장의 그림으로 그렸는데, 좌측은 현실의 인간세상을 그렸고 우측으로 갈수록 산천이 점차로 기기묘묘해 지다가 우측에 도달하면 무릉도원이 나타나는 그림으로서 한장의 그림으로 나타나 있지만 출발부터 도착까지의 과정을 한장으로 표현한 요즘말로하면 파노라마식 그림이라는 것입니다.

그래서 동양화를 감상할 때는 병풍이나 두루말이로 만들어서 펼쳐가면서 보도록 되어 있습니다.

시점이 다르다보니 서양화는 한 부분만 잘라 놓으면 그림으로서의 완성도가 훼손되어 버리지만 동양화는 시점마다의 독립된 그림들의 조합이기 때문에 전체도 보기 좋지만 부분 부분을 잘라 놓아도 완성도가 훼손되지 않는다는 잠점이 있습니다.

끝까지 읽어주셔서 감사합니다.

그래서 얘긴데 제가 항상 여러분들한테 강조하는 게 있어요.

우리말하고 영어는요.

동양화와 서양화의 차이점이다.

제가 아마도 여러분들한테 강의한 것 중에서

여러분들이 명심해야 될 게 이건지도 몰라요.

동양화의 서양화의 차이점이 뭔 줄 아세요?

서양화는요. 색칠을 다 해야 돼. 흰색도 남으면 안 돼.

그런데 우리나라 그림은요. 여백이 많아요.

건데, 서양화는요.

슬슬 색칠 하다말면 미완성이라고 얘기하지만은요.

우리나라 그림은 여백이 있어야 완성이에요.

무슨 말이냐?

우리말 속에는 여백이 많다는 거고, 일일이 말을 표현하지 않는다 이거야.

그래서 제가 어떤 얘기 많이 하느냐 하면요.

‘나 가슴이 아파요’ 라고 얘기하는 것도 영어로 옮기면은

상황에 따라서 영어는 다~ 다르다 이거야.

그런데, ‘가슴이 아프다’ 얘기할 때는요.

폐질환도 가슴 아픈 거구요. 심장마비도 가슴이 아픈 거구요.

정말로 뭐라고 그럴까. 가슴이 쓰린 것도 가슴 아픈 거구요.

정말로 마음이 슬퍼지는 것도 가슴이 아픈 거구요

연탄 깨스 마셔서 허파가 쑤시는 것두 가슴이 아픈 거다. 이거에요.

그러면은. ‘가슴이 아파요’라는 말을 영어로 옮길때는.

잘못하다가는요. 정말로 심장병 환자도 만들고.

이상한 번역이 된다 이거야.

그래서, ‘가슴이 아파요’ ‘니를 보니 마음이 아퍼’

그럼 예를 들어서 그렇게 얘기를 하더라도요.

예를 들어서, ‘I have a heart-attack .' 그러면은.

‘너 보니까 나 심장병 걸렸어.' 그런 말이잖아요. 그게 아니라.

‘I feel sad.' 'I feel sorry.' 이런 말이잖아.

‘너 보니까 안됐다.’ 그런 말이잖아.

예를 들어서 ‘허파가 아프다.’ 그러잖아요.

허파가. 가슴이 아프다도 들어가거든.

그러면 걔네들은요. I have a lung disease. 그래요.

lung이 허파잖아요. 그럼 ‘허파에 병이 걸렸다.’

그래두 가슴이 아퍼. 그런 식으로 표현을 하는데 우리말은 아니다.

이래서 내가 우리말을 영어로 옮길 때마다

‘가슴이 아포’(하선생님만의 특유의 말재치!)

왜? 고민을 해야 되니깐.

우리말은 여백 때문에 여러분들 고 잘 해석하지 않으면요.

이상한 번역이 될 수가 있어요.

동양화 서양화는 우리나라에서 사용하는 용어로 미술에서 회화의 재료나 화법에따라 분류된 용어입니다. 요즈음에는 미술의 형태에 따른 분류를 평면(회화)과 입체(조각)로 분류합니다. 우리나라에서 불리어지는 동양화는 먹을 사용하여 화선지나 비단에 그림 그림을 총칭하기는 하지만 서양화를 전공한 작가들도 먹과 화선지를 사용하기도 합니다. 요컨대 동양화와 서양화라는 것은 서양과 동양의 지역적 분류와 재료 사용에 따른 편의적인 분류입니다

먼저 서양화는 서양의 전통적인 재료와 화법을 이용하여 그린 그림을 말합니다. 재료에 따라 유화·수채화·펜화·연필화·파스텔화·크레용화 등으로 나뉘며 표현형태에 따라서는 구상화·비구상화로 나눌 수 있습니다. 서양화는 논리적이며 화면에 덧바르거나 깎는 식으로 층을 구성한다. 반면 동양화는 동양의 전통적인 재료와 화법을 이용하여 그린 그림으로서 직관적이며 되풀이하지 않고 한번의 터치로 그려지는 그림입니다. 한국·중국·일본 등에서 발달한 독특한 화풍과 화법의 그림으로 주로 먹을 사용하며, 화선지나 비단에 산수·사군자 등을 그립니다. 과거의 중국,일본 한국의 화가들은 모두 투시원근법과 명암법을 중요하게 여기지 않고 평면적으로 그렸으며 텃치와 선, 여백과 공간을 중요하게 여겼습니다. 동양화는 서양화의 특징인 논리적이고 과학적인 원근법을 사용하기보다 여백과 정신을 강조합니다.

그렇다면 동양화와 서양화의 공통점과 차이점에 대해 알아보겠습니다. 일단 동양화와 서양화라고 부르게되면, 회화의 종류를 두 가지 분류로 분리하여 칭하는 것이 됩니다. 즉 회화의 개념을 이분법적으로 구별한 개념이라는 것입니다. 그렇게 회화를 두 종류로 구분을 했으니, 둘은 재료나 내용, 형식에 있어서 당연히 많은 차이를 지니게 됩니다. 그리고 공통점은 자연히 회화의 특성이 될 것입니다. 예를 들자면 인간을 여자와 남자로 구분하는데, 여자와 남자를 구분했으니 차이점은 어느정도 명백하게 떠오릅니다. 그런데 여자와 남자의 공통점을 얘기하게 된다면, 그것은 인간의 특성이라는 것과 마찬가지의 맥락으로 해석할 수 있습니다. 붓을 사용한다는 재료상의 특징이나, 붓이 화폭에 닿게 되면서 어떤 형상이 생기게 된다는 것 등 회화의 특징은 그 공통점이라 할 수 있습니다. 우리 나라도 여인의 아름다운 한복을 강조하여 그리는데 르네상스 시대의 서양 인물화는 인간의 모습을 귀엽게 그렸습니다. 바로 인간의 아름다움을 아주 잘 표현하려 노력했다는 게 공통점입니다.

동양화와 서양화의 가장 큰 차이점으로는 동양화는 중국 한국 일본 등의 아시아권 미술이고 서양화는 유럽 쪽의 미술이라는 것입니다. 일단 눈으로봐도 동양화는 주고 먹, 다시말해 먹물을 주 재료로 쓰며 먹의 농도로 명암을 표현합니다. 반면 유화물감 아크릴 물감 흔히들 사용하는 수채화 등의 재료를 사용하는게 서양화 입니다. 서양화는 초기부터 칼라로 그려졌으며 그림의 밀도가 매우 높습니다. 멀리서 얼핏 보면 실제 사물과 착각을 일으킬 만큼 중간색이 많기 때문입니다. 서양화의 경우 대부분 다양한 칼라를 사용하는 유화가 대표적인데 반해 동양화는 거의 수묵화입니다. 서양화는 화선지에 그리는 동양화에 비해서 켄버스에 그리는게 특징입니다. 원근에 대해 비교하자면 동양화는 사물이 멀수록 밝고 제일 가까운 것을 어둡게 그립니다. 그러나 서양화는 반대로 가까이 있는 사물이 밝게 처리됩니다. 서양화는 이른바 눈에 보이는 대로, 꼭 정말 그것인 것처럼을 추구하기 때문입니다. 따라서 서양화에는 동양화에 없는 투시도법, 명암법이 발달했습니다. 이에 비해 동양화는 "눈에 보이지 않는 것"도 중시합니다. 동양화의 특징은 여백의 미에 있다고 합니다. 대상을 그리고 생각을 표현함에 있어서 서양화는 그대로 보여주는데 반해 동양화는 그것을 보여주면서 다른 어떤 것을 요구합니다. 그것은 이성을 중시하며 합리적인 서양과, 감성을 중시하며 합리적이기 보다는 감정의 문제가 많은 동양과 서양의 감성의 차이라 할 수 있습니다. 또한 동양화와 서양화는 풍경화를 보면 차이가 확연히 드러납니다. 동양화는 한 풍경화에 일점 투시도법을 적용하는 것이 아니라 풍경을 감상하는 사람이 절벽을 돌아서는 부분에서는 정말 절벽을 돌아설 때 보는 시점 즉 밑에서 위를 쳐다보는 시점으로 절벽을 그려넣습니다. 풍경을 감상하려 들어설 때는 멀리서 보는 시점이구요. 한자리에서 눈으로 직접 보고 그리는 진경산수화 이전까지는 이런 관념적인 산수화였습니다. 진경 산수화에서도 주관적으로 산수를 축약하는 것은 여전합니다. 여하튼 서양화는 사물을 객관적으로 똑같이 그리는 것이 발달한 반면 동양은 주관적, 관념적인 것이 중시되었습니다. 요즘의 이른바 포스트모더니즘에서는 동양화에서는 일찍부터 주목해온 주관적인 시각, 관념을 중시하고 있습니다.

동양화는 서양화에 비해서 그림의 수준을 판별하기가 수월합니다.

붓놀림이 얼마나 부드럽고 경쾌하면서도 힘찬지 보면 알 수 있습니다.

이것만 보자면 아마도 장승업 그림이 가장 탁월하겠지만

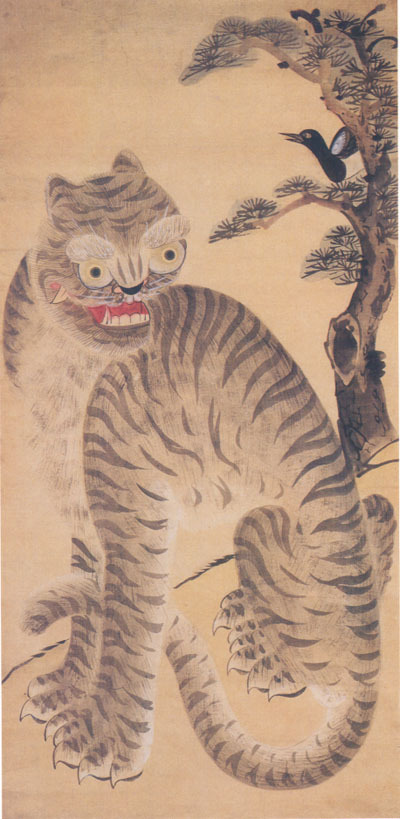

여기서는 기에 관한 이야기인 만큼 여기에 초점을 맞춥니다. 먼저 아래 그림.

<신위의 묵죽화>

동양화와 서양화의 차이점은 대충 다음과 같습니다.

첫째, 동양화는 여백을 강조합니다. 여백은 그저 빈 것이 아니라

기로 꽉 찬 공간, 태허이며 사물은 그것에 의해 비로소 하나의 사물로 나타날 수 있습니다.

둘째, 서양화는 빛에 의한 원근을 강조하는 방면 동양화는 사물 자체가 빛을 머금습니다.

그래서 서양화는 빛의 소실점을 중심으로 거리가 배분되지만

동양화에서는 채색을 강하고 엷게 하는 방식으로 거리라기보다 기-느낌을 나타냅니다.

셋째, 서양화는 사물의 형식미를 강조하는 반면, 동양화는 사물을 탈형식화합니다.

그리하여 사물이 지니는 기운을 드러내려고 합니다.

위의 묵죽화는 제가 말한 특징을 고스란히 가지고 있지요.

이런 특징으로 인해 동양화는 사실적인 묘사에 충실히 해도 겉모습이 아니라

모습이 머금은 기운이 드러나게 마련입니다. 아래 그림을 보세요.

<윤두서 자화상>

그림에서 보시다시피 털 한올한올이 아주 섬세하게 그려져 있습니다만,

서양의 인물화와는 확연히 다르지요?

보이는 것을 통해 보이지 않는 것을 보여주는 것.

동양화의 특징인 여백과 생략은 세계의 기-특질을 드러내기 위해 필수적인 요소이지요.

아래 그림은 산의 허리를 생략해버림으로써 오히려 그 장대함을 드러낸 빼어난 그림입니다.

<곽희의 조춘도>

옛날 이야기 하나.

한 부자가 아주 좋은 병풍을 구한 후 그 병풍에 글씨를 써 줄 사람을 찾았습니다.

워낙 좋은 병풍이라 사람들이 이에 걸맞는 글을 써기가 힘들어 감히 청하지 못했는데,

한 걸인이 찾아와 자기가 써보겠노라고 자청합니다.

사실 이 걸인은 붓글씨를 몰랐고 그저 며칠이라도 잘 먹어보려고 거짓말을 한 것입니다.

마음준비를 해야 한다고 차일피일 미루다가 결국 병풍에 글을 쓰게 되었는데요,

이 걸인, 고심을 하다가 한 일자를 쭉 긋고는 붓을 던지고 달아납니다.

부자의 하인들에게 쫒긴 이 걸인은 돌부리에 걸려 넘어지고는 그 자리에서 죽습니다.

몹시 실망한 부자는 그 병풍을 사랑채 한켠에 치워놓습니다.

그런데 어느 날 한 스님이 왔다가 이 병풍을 보고 몹시 감탄합니다.

부자가 의아해하자 그 스님이 ‘일생일대의 일획’이라고 설명합니다.

기술이 아니라 기운이 중요합니다.

그런데 그 기운은 그리는 사람과 사물이 맞닿는 자리에서 일어나는 것이지요.

다시 말해 그림은 또한 그린 사람의 정신을 나타내는 것이기도 합니다.

그래서 매국노로 유명한 이완용은 조선 후기에 가장 난을 잘 친 사람이지만

그의 그림은 단돈 10원의 가치도 없는 반면 김구 선생의 글씨는

기술적으로 뛰어나진 않더라도 누구라도 갖고 싶어하는 것입니다.

이 방면으로 가장 유명한 그림은 아마도 추사 김정희 선생의 세한도일 것입니다.

<세한도. 문인화의 대표적 그림>

추사체는 워낙 유명하니 따로 설명하지 않겠습니다. 대신 일화 하나를 소개합니다.

어떤 글을 잘 쓰는 사람이 배를 타고 강을 건너려고 하다가 돌에 새겨진 글을 봅니다.

옛날 유명한 사람의 글이라지만 그 사람이 보기에는 별로 신통치 않았습니다.

그래서 그는 그 옆에 자신의 글을 쓴 다음 우쭐해 했지요. 그런데..

나룻배를 타고 가다가 그는 저만치 떨어진 자신의 글을 봅니다.

돌에 새겨진 글은 오히려 또렷이 보이는 반면 자신의 글을 점점 흐려집니다.

기운을 제대로 보이려면 단박에 드러내야지 꾸밈은 오히려 방해만 될 뿐입니다.

이를 박(樸)이라고 하며 그 기예를 졸(拙)이라 합니다.

아래 그림을 보세요.

<탈춤-운보 김기창의 그림>

운보선생은 만년에 마치 어린아이 같은 그림을 그립니다.

제가 한 미술학도에게 짐짓 “이런 그림은 아무나 그릴 수 있는 거 아닌가?”

라고 물었더니, 보기에는 쉬워도 결코 다른 사람이 넘볼 수 없는 공력이 담겼다네요.

다음은 서양화입니다.

서양에는 없는 개념인 기로 서양화를 감상할 수 있는지 의아해 할 수 있을텐데,

물론 가능합니다.

기로 보면 세계는 이루 말할 수 없이 다양한 모습을 자신 안에 품고 있으며

화가는 수 없이 많은 습작을 하면서 점차 자신이 느끼는 세계의 한 특질을 잡아냅니다.

아래 그림은 고흐가 많은 습작을 통해 완성시킨 그림입니다.

<씨뿌리는 사람>

이 그림은 태양을 중심으로 빛이 뻗어나갑니다만, 그 힘은 조금도 줄지 않으며

강렬함이 그림 전체를 휩쓸고 지나갑니다.

햇빛에 의해 드러난 색체가 그 강렬함으로 사물들을 녹이고 엉키게 하고 있지요.

혹 매가 공중에서 거의 정지한 모습으로 있는 것을 보신 적이 있으신지요?

아시다시피 공중에서는 나는 것이 더 쉽지 정지하기란 결코 쉽지 않습니다.

뭐, 과학에서는 매가 상승기류를 타고 있어서 그렇게 할 수 있다고 설명하지만

그 모습을 보면 평안한 것이 아니라 대단한 강렬함이 느껴집니다.

고흐의 해바라기는 정물화이지만 공중에 정지된 매와 유사한 힘을 느끼게 합니다.

<해바라기>

서양화가 한 사람만 더 소개합니다.

클리는 대단히 독특한 선으로 그림을 그리는 화가인데요,

그의 선은 부드러우면서도 힘차고 어린아이 같으면서도 현묘한 느낌을 줍니다.

그 덕분에 그는 보이지 않는 모습을 그리는데 탁월한 솜씨를 발휘합니다.

<지저귀는 기계>

어떤가요? 새의 노래가 들리는 것 같은지요?

일담 하나.

전에 한국의 유명한 화가 작품의 진위 여부로 큰 소동이 벌어진 적이 있습니다.

국립박물관의 전문가들은 그것이 진품으로 판정했는데,

문제는 그 그림을 그린 작가가 가짜라고 주장한 것이 발단이 되었지요.

이에 대해 만화가 고우영씨가 이런 말을 했지요.

자신은 그저 만화쟁이에 불과하지만 십년 전에 들판을 표시하기 위해

약간 휘어진 선을 그려놓은 것도 그것이 자신이 그린 것인지 판별할 수 있다고 합니다.

그런데 그 뛰어난 화가가 자신의 그림도 구분하지 못한다는 것은 말이 안된다고요.

그 화가가 무슨 사정이 있어 거짓말을 했는지도 모르겠지만, 여기서 중요한 점은

자신의 그림을 보는 화가의 눈과 전문가의 감정의 눈은 확연히 다르다는 점입니다.

아시겠지요? 그 차이가 무엇인지?

마지막으로 제가 좋아하는 클리의 그림 하나를 더 소개합니다.

< 식물과 대지, 공기의 영역 스케치 >

잠재성의 바다인 이 세계를 제대로 느끼려면 형식적 격자를 돌파하여야만 하며

그리하여 드러난 무한한 기-느낌의 세계로 들어가야만 합니다.

그 좋은 수단이 바로 미술입니다.

그림은 눈으로만 보는 것이 아니라 눈을 통해 신체로 감상해야 하며,

그리하여 화가가 느낀 그 세계로 빠져들어 보아야 하는 것이지요.

감상(感想)은 모습(相)이 마음(心)으로 들어오는 것이며

이를 씹어서(咸) 마음(心)이 되게 하는 행위입니다.

즉, 감상이란 자신의 존재가 그 그림을 통해 변모하는 행위인 것입니다.

동양식 꽃꽂이

동양식 꽃꽂이는 서양식 꽃꽂이 보다는 화려하지는 않지만, 미적 표현요소인 선을 강조하는 방식으로 선을 다양화 시킴으로써 내면의 미를 느끼게 한다. 직선은 강직하고 힘이 있어 보이게 하며, 곡선은 유연하고 섬세한 느낌을 주게한다.

대개 천(天), 지(地), 인(人)-(하늘,땅,인간)의 조화를 생각하여 3개의 주지로 삼아서 1주지,2주지,3주지의 칭호를 붙이면서 그림 상으로는 1주지는 ○로, 2주지는 □로, 3주지는 △로 표시한다.

동양식 꽃꽂이의 종류로는 직립형, 경사형, 하수형, 평면형, 분리형이 있다.

동양화를 표현할때는 세주지를 부등변 삼각형으로 구성, 대자연의 사실적 묘사, 선의 간결한 아름다움과 꽃과의 조화, 공간과 여백의 미를 강조, 음양의 조화, 움직이는 동,정을 살펴서 표현을 하는것이 좋다.

서양식 꽃꽂이

서양식 꽃꽂이는 미국을 중심으로 발전한 스타일로서 기원전 2800년 고대 이집트시대 부터 내려오던 유럽 정통 스타일이 영국의 영향으로 발달하여 내려온 것이다. 서양식 스타일은 종교적 요소에 합리적 사고방식, 시대 환경에 맞는 기능이나 장식성에 의한 표현에 중점을 두고 있다. 꽃의 모습을 그대로 재현하는 것뿐만 아니라 인공적인 기교를 가해 실내장식, 의상장식의 일부로서 생활 속에 활용되어 직업적 활용도와 상품적인 가치가 크게 발전된 실용화된 디자인이다.

서양식 꽃꽂이의 종류로는 수직형, 수평형, L자형, 삼각형, 사각형, 원형, 초생달형, S자형, 반구형, 구형, 원추형, 방사형의 있으며 꽃의 모양 및 형태에 따라 Line 플라워(선을 표현-글라디올러스,금어초,리아트리스 등), Mass 플라워(디자인의 양감을 표현-장미,국화,카네이션 등), From 플라워(꽂자체가 아름답고 색깔이 화려한 시각상의 포칼포인트-카라,극락조화,안스리움 등), Filler 플라워(라인과 매스의 부족한 공간을 메워줌-과꽃,소국,안개 등) 나눌수 있다.

*입시 동양화를 잘 하기 위해서는 먼저 동양화와 서양화의 차이점을 정확하게 알고 그림에 임해야 할 것이다.

-동양화와 서양화의 차이점

동양화란 동양의(한국.중국.일본..등)전통적 기법과 양식에 의해 다루어진 회화를 말하며 서양화와 대별되는 용어이다.

동양의 문화권에 있어서 한국의 전통회화는 한국과,중국의 전통회화는 중국화, 일본의 전통회화는 일본화로 정한다.

-회화의 기본요소는 점, 선, 면인데

동양화는 획 즉 선의 예술로서 사물의 내부본질을 파악하는 것이며 화선지나 비단 등에 수간 안료를 사용하고 모필을 이용하여 그리며, 표현양식에 달라 수묵화, 수목담채, 채색화 등으로 구분되며 표현형식에 따라서는 문인화, 구상, 비구상등으로 나뉜다. 동양적 자연관과 철학에 바탕을 둔 회화관과 화론에 입각하여 그리는 그림이며 주로 중국의 전통 회화관과 아주 밀접한 관계를 갖고 있다.

서양화란 현상적으로 사물의 외부로부터 분석하여 체계를 세우려는 빛에 의한 면의 예술이라 하겠다. 재료적인 측면에서 유화, 수채화, 펜화, 목탄화, 콘테화, 연필화, 파스텔화, 크레용화, 과슈화...등이 있으며 표현형식에 따라 구상화. 비구상화로 나뉘며, 동양 문화권에 서양화가 알려지면서 동양의 그림(중국, 한국, 일본 등...)즉 동양화와 대별되는 개념의 용어이다.

동양화는 주로 객관적이고 사의적이며 되풀이하지 않고 한번의 터치로 그림을 그리는데 반해 서양화는 지극히 합리적이고 논리적이며 빛에 의한 명암법과 사실성에 중점을 두고 덧칠하고 긁고 깍아내는 그림 수법을 엿볼수있다. 동양화를 시작하기에 앞서 사혁의 화론을 숙지하고 이해하여야만 동양화에서 요구시되는 참맛을 표현할수있으리라 본다.

*사혁의 화론육법

:사혁은 AD510년경의 중국의 화가로서, 그가 세운 동양회화론은 이론에 있어서 가히 시조라 할 수있을만큼 고대회화를 체계적이며 과학적으로 정리했다. 그의 화품론은 후일 많은 화가들에게 영향을 끼쳤으며, 특히 이론적으로 후세에 지대한 영향을 미쳤다. 그가 저술한 고화품록은 육품론이 정리 된 것이며, 화품이란 화가들의 우열을 말하는 것으로 모든 화가들은 이 육품에 의해 서열이 정해졌다.

:화론육법

기운생도, 골법용필,웅물상형,수류부채,경영위치,전이모사, 등인데 그 뜻을 알고 그림에 임하여 한층 격있는 작품을 만들어보자...^^

1.기운생동...정기론에 근거하였고, 사물을 대할때 어떻게 기를 살려 표현할 것인가 하는 것으로 정신적인 감정과 공간적인 감각, 운율적인 감정, 생명감과 생동감등을 표현하는 문제이다.

2.골법용필...대상을 표현하는데 있어서 용필, 즉 붓의 사용을 뜻하는 것으로 골법이란 골자, 즉 뼈대를 말하는 것이며, 또한 운필이란 동양화에서는 생명과 같은 것으로 이 용필이 서툴면 그림은 생명력을 잃게 된다.

3.웅물상형...대상을 그리는데 있어서 윤곽을 정확하게 하여 형상을 사실적으로 표현하는 것을 만하며 윤곽과 정신이 일치했을때 비로소 형상과 내용을 표현할 수있다는 것을 의미한다.

4.수류부채...모든 사물에는 고유의 색채가 있으므로 채색을 바로 하지 않으면 그 물체의 빛깔을 잃어버리게 된다는 것이다. 느낌과 형태에 따른 색감을 회화적으로 잘 표현해야 한다는 것으로 필법과 윤곽, 생감이 잘 어우러져야 함을 말한다.

5.경영위치...화염의 포국, 즉 그도를 말하는데, 그림을 그릴때는 주제와 부 주제 등의 위치가 잘 위치해야 하고 또 다른 모든 사물들이 잘 배치, 배열되어야 함을 말한다.

6.전이모사...옛 선조나 스승의 그림을 모방하여 그리는 것을 말한다. 하지만 중국 육조시대의 그림공부는 이화로부터 시작했다고 하는데, 이화란 모사를 말하는 것이 아니라 자연의 경관을 어느 만큼 잘 옮겼는가를 뜻한다.

이처럼 사혁의 화론육법은 그 후 많은 화가들에 의해 연구 습득되어 발전하였으며, 화가 자신들의 생활과 경험속에 반영되어 왔다. 화론육법은 회화창작에서 요구되는 예술성을 계통적으로 지적해 냄으로써, 이때부터 창작또는 평론상으로 작품에 대한 우열을 가리는 기준이 되어왔다고 한다. 입시동양화 또한 위와 같은 화론에 입각하여 그림에 임한다면 좋은 작품평을 받을 수 있으리라 본다.

*선과 여백

입시에서 실기고사내용이 수묵담채화인데 여기선 선과 여백의 의의를 알아보자

-수묵화는 농담조차도 면으로 표현하지 않고 선으로 표현한다.

대상물의 색상을 뛰어넘어 그 내면의 기의 흐름은 어떻게 생동하는 것으로 표현할 것인가에 큰 비중을 두어야 한다.

남제의 사혁이 고화품록에서 주장하고 있는 당의 장언원이 화론육법에서 의미를 밝혀 기운생동을 첫째로 한것은 바로 기의 생동을 철학적인 고차원의 예술에서 해석한 것이다.

수묵화는 이와 같은 동양적 사고의 정신성을 나타내는 대표적인 예술이며 대상을 포착하여 마음으로 그것을 연소시켜 단순한 획(선)으로 화면에 정착시카는 것이다.

따라서 생략과 단순화는 수묵화의 가장 큰 특징이며, 그리지 않고 남겨 둠으로서 그리는 여백은 형상의 묘사에 그치지 않고 마음을 그리는 것이며 여백은 비어 있는 공백이 아닌 채워진 상태, 곧 표현의 저장인 것이다.

-동양화의 대표적인 수묵화는 표현방법이 대담하고 거침없는 필력과, 선의 단순함이 아닌 농담의 다양한 변화의 묘를 간직한 획(선)으로 그림을 그림으로써 세부적인 묘사를 암시적이고 은유적으로 처리한다. 그러므로 화선지에 붓을 대기전에 어덯게 표현할 것인가, 어떤 순서로 그릴 것인가 등의 기법 적인 면에서 계획을 세워 그림을 그려야 할 것이다.

따라서 사생(스케치 및 계획)을 충실히 하여 대상물의 형태나 그 성격을 잘 파악하고 대상을 자유자재로 그릴수있어야만 비로소 그릴수 있는 것이다.

선과 농담의 변화를 익혀보자

회화의 기본요소는 점, 선,면이다. 동, 서양화의 본질은 동일하지만 표현양식에 있어 동양화는 선의 예술이고 서양화는 빛에 의한 명암의 대비로 표현하는 면의 예술이라 할 수있겠다. 동양화에서의 선은 외곽형상의 의미에 그치는 것이 아니라 사물의 본질과 질감 및 양감을 함축적으로 표현하는 것이므로 그 뜻을 알고 필선의 운용에 유의해야 할 것이다.

수묵담채화에 있어서 중요한 것 중의 하나가 먹색의 짙음과 엷음을 적절히 사용하는 것이다. 먹색을 자유롭게 구사할 수 있어야 원하는 느낌의 그림을 얻을 수 있다.

물과 먹의 배율에 따라 그 변화가 수없이 많은데 적재소에 적합한 먹색을 올릴수있도록 물과 먹의 배합을 적절히 해주어야 하겠다. -먹색을 짙음, 중각, 옅음(농.중.담)으로 구분하여 3색이라고 하며 먹을 사용함으로써 나타나는 현상에 따라 검정, 짙음, 젖음, 마름, 엷음으로 구분한다.

다음은 동양화를 그리는 수법 중 붓 쓰는 방법과 그리는 방법 등을 알아보기로 하겠다.

-중봉...서예가나 화가드링 가장 선호하는 필법이며 붓을 다섯 손가락 모두 사용하여 단정하게 잡고 붓대를 지면과 수직으로 바로 세워 긋는 선이며 입시동양화에서는 주제부에 주로 활용한다. 주제의 부각을 꾀하기 위해서는 강직하고 힘차게 그어주는 것이 좋다.

-측봉...붓대는 80도 각도로 우측으로 기울여 운필하고 예리한 표현 및 경쾌한 맛을 살려 주기에 적합하다. 나뭇가지나 대나무 표현 등에 자주 쓰인다.

-역봉...위에서 아래로 긋거나 좌측에서 우로 긋는다든지 붓을 사용하는데는 누구나 습관이 있다. 이러한 운필의 방향을 상반되게 붓의 사용법을 익힘으로써 상하 좌 우 어느방향이든 자유롭게 선을 구사할 수 있게 된다. 대나무를 그릴때 아래서 위로 그리는 법이나 난을 그릴때 우측에서 좌측으로 뻗은 잎을 그리는 법 등이 바로 역봉법이다. 입시동양화에서는 사물의 방향성에 따라 많이 사용되는 필법이다.

-전봉...이 붓질법은 손목과 손을 자유롭게 움직여 손가락으로 쥔붓대까지 굴리거나 뒤틀면서 중봉,측봉,역봉 등을 서로 변환 교환하여 사용한며 풍부한 표현이 가능한 필법이다. 주로 넓은 면을 채색하기에 용이하며 항아리, 벽돌, 혹은 주전자 등의 표현에 활용하면 좋다.

-순봉...붓의 끝은 중봉처럼 중심에 가게 하되 붓대를 경사지게 하여 백합 잎이나 난초 잎혹은 둥근 형제의 정물표현에 있어서 쌍방향 진행선 등의 표현에 용이하다.

-파봉...붓긑을 거칠게 흩으려 붓질하는 법으로 한 획에 여러 갈래의 가는 선이 표현된다. 거친 사물의 질감 표현이나 솜털, 페인트 붓, 페인트, 로울러, 곰인형 묘사 등에 용이하다. 자칫 속기에 빠져 격이 떨어질 수있으니 신중해야한다.

-구륵법...선으로 물체의 윤곽을 그리는 방법이며 선의 강약, 굵거나 가는 여러가지 성질의 선으로 표현하는 묘법이다. 국화나 백합 그리고 대부분의 인공물을 표현할때 주로 사용하며 대체적으로 사물의 정돈된 느김이 장점이라 할 수있다.

간단한 선만으로 표현하는 백묘법과 먼저 채색한 후 나중에 선을 긋는 방법이 있고 먼저 선을 긋고 후에 채식을 하는 구륵 채색법이 있는데 전자는 화훼류에 적합하고 후자는 기물류나 질감이 견고하고 딱딱한 정물표현에 적합하다.

-몰골법..물체의 윤곽을 선으로 표현하지 않고 먹물이나 물감의 농담을 이용하여 그리는 방법이다. 먹물만을 사용하는 방법과 먹과 색을 병용하여 그리는 방법, 먹과 색깔을 혼합하여 그리는 방법, 색깔만을 사용하는 채색화등이 있다.

그냥 집에서 혼자 독학하시는 분들은 중국의 개자원 이라는 책을 사서 공부하는것도 하나의 방법이며 .많의 모방 ,,을 통하여 실력을 키워 나가는 방법이 있다고 할것이며,다른작가의 작품을 우선적으로 많이 보고 이해하는것이 먼저가 아닌가 생각한다.

동양화

축구관계로 수업을 빨리 끝나는 바람에 교수님(추계예대 김 지 현 교수)께 동양화에 대한 이론을 1시간 정도 강의 받았습니다.

동양화와 서양화의 차이점과 색에 대한 철학을 들을 수 있는 시간이었습니다.

조금은 어려운 말씀을 하시어 이해하는 데 조금은 ....

어째거나 동양화는 直觀 (직관)으로 보라는 말씀 ( 그 안의 것을 보라<내 생각>)이었습니다.

붓에 오색 육채를 표현한다고 합니다.

짧은 시간에 많은 것은 기억에 나지는 않지만 여기까지 입니다.

그럼 우리들의 직관을 감상하시지요

공판화

일명 스탠실 이라고도 합니다.

두꺼운 도화지에 밑그림을 그린 후 오려 붙혀서 선을 나타내고 싶은 곳에 덧붙여서 나타내는 것을 말합니다.

그럼감상하시지요

작가;이승희 작품명; 꽃과 나비

작가; 신영준 작품명; 꽃밭에서

작가; 김철회 작품명; 꽃병

작가; 정구봉 작품명; 곰돌이

작가; 노경희 작품명; 오리가 태어났다

작가; 노병호 작품명; 슬리버

작가; 방혜옥 작품명; 사랑스런 꽃이여

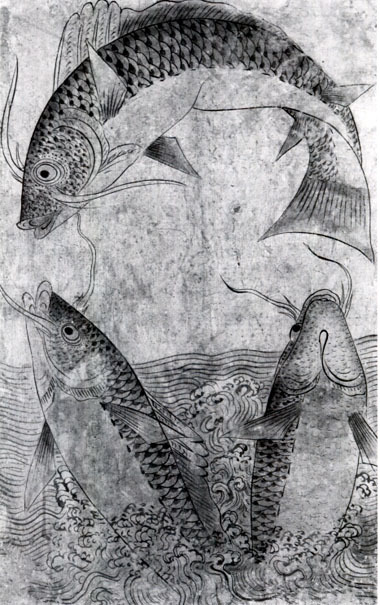

작가; 이현숙 작품명; 금붕어

작가; 작품명; 연 꽃

작가; 민승기 작품명; 삼족오

작가; 장 광 복 작품명; 꽃다발

작가; 우경순 작품명; 미니 마우스

작가; 민승기 작품명; 치우천황

전통적인 관점에서 본 동양화의 관찰방법

---진조복(鎭兆復) 著 <동양화의 이해> 중에서 요약

예술은 생활에서 비롯되는 것으로 회화예술의 표현문제는 먼저 현실생활에 대한 관찰과 인식에서 시작된다. 그러므로 관찰방법을 익히는 것은 그림을 공부하는 데 중요한 과정이다. 그러나 많은 동양화 연구자들은 그 표현기법에는 많은 관심을 보이나, 관찰방법은 크게 중시하지 않는다. 화가에게 눈의 훈련은 음악가의 귀의 훈련과 같은 것으로, 표현기법 역시 눈의 훈련에서 시작되는 것이다.

1. 걸으면서 관찰한다.

동양의 화가들은 어떻게 생활을 관찰하고, 또 어떻게 이를 창작과 연결시키는가? 이에 대한 많은 고사들이 전해오고 있는데 예를 들면 당(唐)의 현종(玄宗)이 가릉지방의 경치를 그리워하여 오도자(吳道子)로 하여금 그려오게 하였는데 오도자는 가릉지방을 둘러보고는 빈 손으로 돌아왔다. 현종이 그 이유를 물으니 `저는 비록 밑그림을 그리지 않았으나 모두 마음속에 담아 왔습니다`라고 답하였다. 훗날 오도자는 대동전이라는 건물에 벽화를 그리게 되었는데 여기에 3백여 리에 걸친 가릉지방의 풍경을 담아 하루 만에 완성하였다고 한다. 또 남당(南唐)의 고굉중(顧閎中)이 그린 <한희재야연도(韓熙載夜宴圖)>는 몇 개의 서로 다른 장면을 다른 각도에서 포착하여 연회의 장면을 묘사한 것으로, 각 장면들은 병풍을 이용하여 구분 짓되 자연스럽게 연결되도록 하여 한 작품으로 완성한 것이다.

이러한 고사들은 동양의 화가들이 그림을 그릴 때 어떤 고정된 시점에서 특정한 시야 안의 사물을 관찰하고 묘사하지 않음을 설명해준다. 화가들은 걸으면서 보고 생각하면서 대상의 각 방면을 관찰하게 되며, 그 후 대상을 떠나 대부분을 형상기억에 의해 창작을 하였다는 것을 알려준다.

서양회화와 비교하여 보면 그 차이점이 더욱 분명해지는데 전통적인 서양화는 사생을 중시하고 사생 때에는 특정한 시간과 장소, 일정한 거리와 각도에서 그 시야 안의 사물을 관찰하고 묘사한다. 그래서 화면 안의 명암과 색채의 변화는 특정한 시간과 공간의 객관적인 요소의 제한을 받게 된다.

동양화가들이 사용한 이동시점(移動視點)은 `마치 산이 가로 막히고 물이 끝나 길이 없을 듯하지만 버드나무 우거지고 꽃이 피어있는 사이에 또 하나의 마을이 있다`는 옛 시인의 시구와 같은 것이다.

초기 산수화에서부터 이동시점의 이른바 `산의 모습은 걸음에 따라 변하고``산의 면면을 모두 본다`라는 묘사방법은 이미 존재하였다. 동진(東晋)의 화가 고개지(顧愷之)의 <화운대산기(畵雲臺山記)>에서도 이에 관한 내용을 찾아볼 수 있다. 동양화는 그 화면에서 반드시 하나의 고정된 초점과 하나의 분명한 지평선, 혹은 수평선을 필요로 하지 않는다. 이것이 걸으면서 관찰하는 동양화의 관찰방법이다.

노신(魯迅)이 `서양인들은 그림을 볼 때 보는 이를 어떤 정해진 지점에서 감상하는 것으로 여기나 동양화는 그렇지 않다`라고 한 말은 바로 동양화와 서양화의 관찰방법 차이를 정확하게 지적한 것이다.

2. 모양을 버리고 정신을 취한다.

전통적인 동양미술은 대상이 되는 사물을 단순히 어떤 한 곳에서 생각하거나 관찰하거나 묘사하지 않는다. 관찰에서 묘사에 이르기까지 개괄과 취사선택을 거쳐야한다. 이것이 바로 `유모취신(遺貌取神)`이다.

동양화는 전면적인 관찰을 강조하면서 동시에 대담한 취사선택을 요구한다. 즉 정신이 깃들어 있는 부분은 될 수 있는 한 분명하게, 정확하게, 특출하게 공들여 표현하고 그 나머지 배경을 포함한 덜 중요한 부분은 최대한 간략하게 하거나 생략해 버리는데, 이러한 부분은 여백으로 대체된다.

일상생활에서도 자신의 이상이나 필요에 부합되는 것은 주의를 기울여 보고, 관계없거나 필요없다고 여겨지는 부분은 관심을 덜 갖게 마련이다. 그렇기 때문에 동양화가들은 기계적인 자연 모방을 경계했으며, 이러한 그림을 비록 자세하고 세밀하나 생기가 부족한 죽은 그림으로 간주하였다.

동양화가들은 현실을 관찰할 때 시종 느낌이 가장 크고 깊으며 가장 생동하는 면을 포착하였으며, 창작에 임할 때도 이렇게 포착한 것을 결코 잃지 않았다. 청(淸)나라 때 양주팔괴(楊洲八怪)의 한 사람인 이방응(李方膺)은 그의 매화 그림에 `분방하게 핀 매화 중 가장 마음에 드는 것은 단지 두세 개의 가지일 뿐이니, 그 두세 가지만 빼어나게 표현하면 될 것 아닌가`라는 시구를 적었다. 단지 그 가장 아름다운 두세 가지만을 화폭에 담고 나머지는 모두 화폭 밖에 놓아두어 보는 이들로 하여금 상상에 의해서 보충하고 발견케 한다.

‘유모취신’은 예술적인 중요한 형상을 돋보이게 하며, 동시에 보는 이에게 더욱 넓은 상상의 여지를 남겨주어, 눈앞에 펼쳐지는 경치 이외에 다하지 못한 또 다른 의미까지도 작품에 포함시키는 것이다.

3. 조직구조에 주의한다.

동양화가들은 각기 다른 시점, 다른 각도에서 느낌이 제일 강한 인상을 관찰하여 이를 하나의 화면에 돌출되고 과장되게 표현하기 때문에 작품에 종종 명암을 생략한다. 빛과 명암은 모두 객관적인 것들인데 왜 이를 표현하지 않는가? 그 이유는 작가가 사물을 관찰할 때 여러 각도에서 관찰하기 때문에 고정된 빛을 묘사할 수 없을 뿐 아니라, 서양화에서와 같이 빛으로 어두운 면과 밝은 면을 구별하는 방법을 사용할 수 없기 때문이다. 이렇듯 동양화의 관찰방법은 명암을 배제하고 대상의 조직구조에 주의하게 되어 있다.

동양화가는 작업에 임하기 전에 반드시 세밀한 관찰과정을 거쳐 대상의 생장법칙과 조직구조를 파악한다. 예를 들면 인체의 비례와 해부학적 규율, 바위의 체적과 질감, 나무의 생태 등을 자세하게 익히고 표현방법을 훈련한다.

동양화가들은 오랜 창작경험을 토대로 하여 대상의 각종 구조로 표현양식을 만들어내게 마련이다. 산수화에서의 각종 나무나 바위를 그리는 법과, 화조화의 여러 가지 새와 꽃의 조직구조와 그 화법, 인물화에서의 얼굴과 각종 옷주름을 표현하는 방법 등이 그것이다. 이러한 기본적인 규칙들을 익히고 난 후에야 비로소 현실에 대한 관찰 역시 바탕이 있게 되어 현실 중 어떤 것을 취하고 어떤 것을 버려야 할지 알 수 있게 된다.

동양화는 빛에 의한 명암의 변화보다 대상의 구조묘사를 중시한다. 수묵의 농담 변화, 선의 경중, 휘어지고 구부러짐 등은 모두 물체의 조직구조를 표현하기 위한 것이고, 밝고 어두운 선염은 단지 화면의 필요에 따라 배치하는 것으로 화면의 리듬감과 체적감을 증가시키기 위한 것이다. 묵죽(墨竹)을 예로 들면 일반적인 대나무 그림은 그 본래의 명암 변화는 무시되고 형태와 구조만으로 표현되어 왔는데 이러한 형태와 구조는 자연 상태의 대나무가 갖는 가장 본질적인 특징이다. 화가는 대나무의 생장법칙과 그 특성을 잘 이해하고, 필묵의 기교 또한 완전히 숙련한 후에야 비로소 모필(毛筆)이 화선지에 닿을 때마다 줄기, 잎이 드러나고 또 서로 어우러져 바람에 흔들리는 자연스러운 자태를 표현해 낼 수 있다.

Uniqueness of Korean Cusine I

| Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles |

|

| Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles |

|

(6-2, p. 4) KOREAN ART IN WESTERN COLLECTIONS: 11

Sir John Figgess

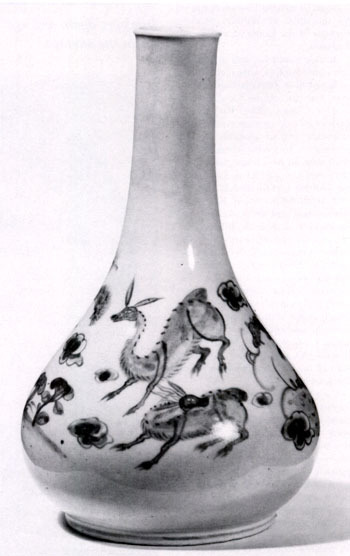

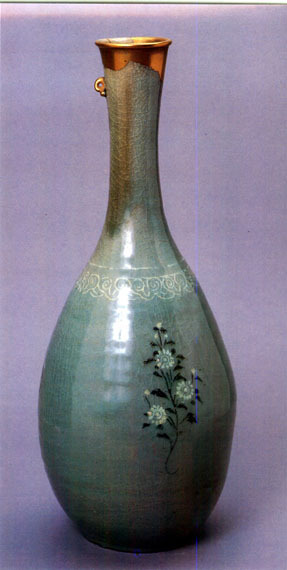

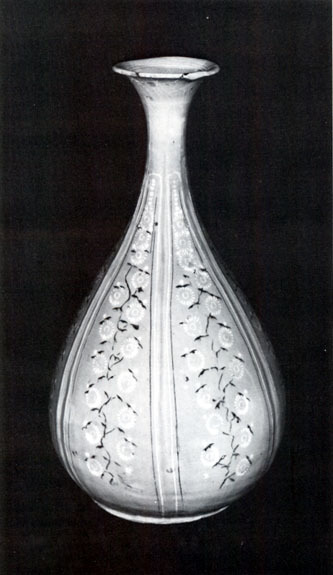

(6-2, p. 5) Throughout Europe until some years after the end of the Second World War, interest in the arts and cultures of East Asia focused predominantly on China and—to a lesser extent—on Japan. The culture of Korea attracted little attention; and it is no surprise, therefore, that awareness of the heights attained by the arts of Korea came relatively late to the British Isles. Indeed, it was not until about 1952 that the pioneering activities of Godfrey Gompertz awakened English connoisseurs of oriental ceramics to the superb quality of the best Koryo celadons which had previously been rarely seen in England. While the broad range of Korea's arts went largely unnoticed, however, this is not to say that the peninsula's ceramics were entirely unknown prior to the war. During the early years of the twentieth century, a fair number of representative ceramic pieces from both the Koryo (918-1392) and Yi (1392-1910) dynasties found their way to England, by way of collections assembled in Korea by resident diplomats or missionaries, or as single items acquired by the rare discriminating visitor. The objects thus collected were generally not, however, of the best quality-which may explain why they failed to arouse great interest among the growing band of enthusiasts of oriental ceramics then active in England. Nevertheless, among these Korean wares were a few notable examples—especially of Yi dynasty porcelains—which attracted the attention of connoisseurs of the time. The renowned collector George Eumorfopoulos cast his discerning eye over many of these pieces, and some of those originally acquired for his collection provided the basis for the collection of Korean ceramics now housed in the British Museum. In 1911, Eumorfopoulos gave to the British Museum one of the first of its Korean works, a pear-shaped bottle vase of the Koryo dynasty (pl. 1). Few examples of Korean ceramics could have been better calculated to stir the interest of the museum's staff than this thirteenth-century vase of glazed stoneware, decorated with panels of chrysanthemum heads inlaid in black and white slip under a greyish-green celadon glaze. The elegant shape and large size of this bottle with its slender neck, flaring mouth, and swelling body mark it as an outstanding example of the Koryo potter's art.

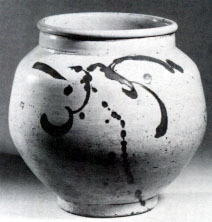

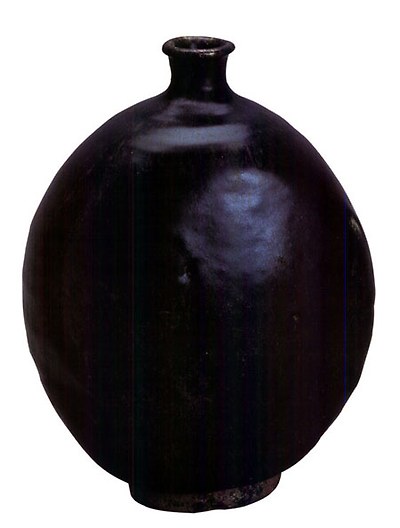

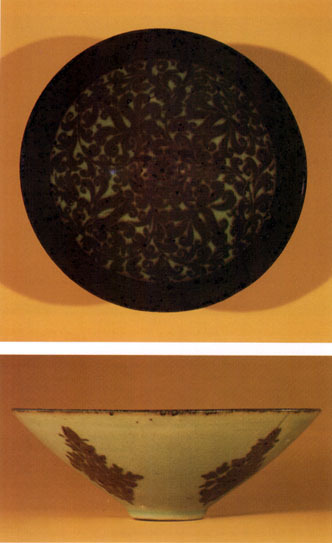

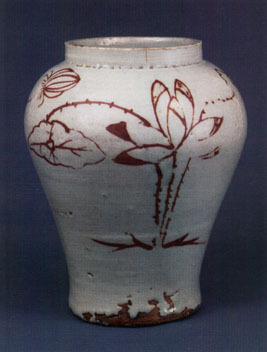

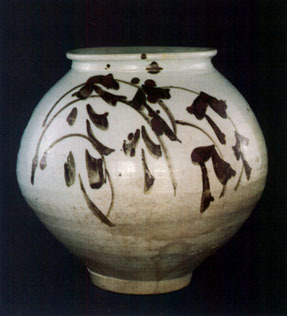

Post-War Acquisitions Since the war, the British Museum has continued to acquire Korean ceramics, some of which are unique in their beauty or significance. In 1946 the museum obtained a faceted porcelain jar of the Yi dynasty, decorated with stamped blossoms under a very pale bluish glaze (pl. 4). As seen in this jar, the faceting of simple basic ceramic forms to produce sharp angles and flat surfaces for decoration was an innovation of Korean potters of the middle part of the Yi dynasty. The technique was subsequently adopted by the porcelain factories of Japan, which employed it widely in the manufacture of arita and kakiemon decorated wares for export to Europe. This fine and unusual faceted jar is technically very advanced and, so far as is known, unmatched by any example of the (6-2, p. 7) type elsewhere. Also now in the collection of the British Museum is a seventeenth-century porcelain jar, decorated in iron-brown under a finely crackled transparent glaze (pl. 5). This strikingly handsome jar was given to the museum in 1957 by K. R. Malcolm; its bold shape and the freedom of its vigorous, almost abstract, iron painting give it an air of modernity.

It is all the more remarkable that Honey could express himself so unreservedly, when we reflect that he had little opportunity to see the finest Korean wares as we now know them in collections in Korea, Japan, and the United States. Among those ceramics that Honey did inspect, however, were some remarkable examples that have remained in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, including a thirteenth century bottle vase of porcellaneous stoneware with inlaid decoration in black and white slip and painting in copper-red under a celadon glaze (pl. 6). In the decoration of this beautiful vase—one of the first Korean pieces to enter the collection of the museum—may be seen the effective use by Koryo potters of the technique of inlaid slip. Here the single sprays of peony and chrysanthemum within roundels, set against the mellow tone of the celadon glaze, exercise a lasting effect on the imagination and seem to attain the highest level of artistry. The blossoms are enhanced by a touch of underglaze copper-red.

'Bold Rendering' It is likely that the use of painted decoration in underglaze copper-red was an innovation of Korean potters during the latter part of the twelfth century. While there is no means of telling whether the use of underglaze copper-red continued into the Yi period without a break, there is ample evidence from kiln sites and literary references to indicate that such wares were being produced during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Relatively few complete pieces from this period have survived, however, and by far the largest number of existing underglaze copper-red painted wares date from the latter part of the Yi dynasty. The Victoria and Albert collection is fortunate in having a fine baluster vase which is unmistakably from the early part of the Yi dynasty (pl. 8). Honey, who particularly admired this rugged jar, regarded it as a test of ceramic appreciation, and described it as the first example to reveal to me the peculiar beauty of the Yi dynasty wares . . .. It is painted in an impure copperred with a bold rendering of a lotus plant. The large gestures of the drawing have an almost sublime quality, and the design fills its space in a most (6-2, p. 9) (6-2, p. 10) satisfying way. 3

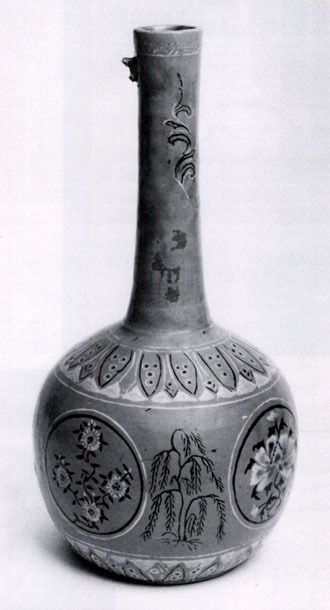

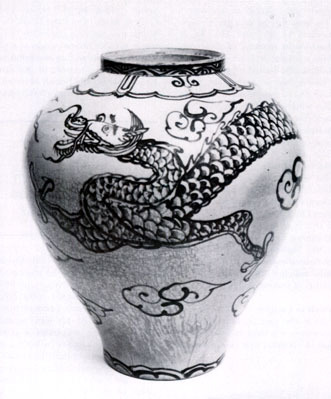

Another of the Korean pots in the Victoria and Albert collection that excited Honey's admiration is its seventeenth-century porcelain wine jar, with painted iron-brown decoration of a dragon among clouds (pl. 9). The hard but immensely vital linear drawing of the fiery dragon, the bold sweep and freedom of the brushwork, and the rich brown of the pigment used in the decoration of this handsome jar command our attention. As Honey wrote of the Yi dynasty painted wares, the decoration of this jar "seems to grow with perfect naturalness out of the very shape of the piece." 4 It seems likely that the widespread use of iron painting in Korea during the middle part of the Yi dynasty was due to difficulty experienced in obtaining cobalt ore for the production of underglaze blue decoration, and the consequent restrictions placed on its use. Looking at this iron-painted jar we may perhaps consider this to have been a felicitous combination of circumstances.

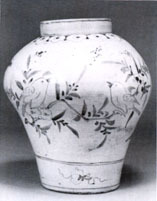

In the same year, the Ashmolean collection received a large globular porcelain jar of the seventeenth century, with painted decoration of a (6-2, p. 12) fruiting vine in underglaze ironbrown and cobalt-blue (see cover). This beautiful jar was given to the museum by Mr. and Mrs. K. R. Malcolm in memory of their son, John, a scholar of Worcester College, Oxford, who died in 1974. It is one of a rare group of high-grade wares decorated in iron-brown and cobalt-blue, which are believed to have been made for the court at the official potteries in Kwangju and at other kilns in the vicinity of Seoul. It is likely that the decoration of such wares was entrusted to skilled artists, who seem to have favored rather elaborate themes such as clusters of grapes or monkeys swinging on grapevines. One frequently illustrated piece of this type is a large baluster jar belonging to Ewha Women's University Museum, Seoul. 5 Although the Ashmolean example is smaller, it fully matches the Ewha piece in quality of potting and decoration.

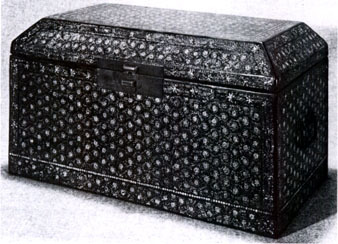

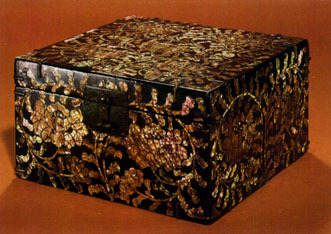

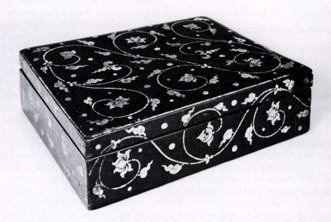

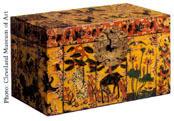

The museum does have at least four fine boxes from the middle of the Yi dynasty, of which two are illustrated here(pls.13, 14).The earlier of these dates to the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, and is inlaid in mother-of-pearl with a design of (6-2, p. 13) chrysanthemum flowers and foliage, and has bronze fittings (pl. 13). This lacquer box is of superb quality and in excellent condition. The shell inlay is multicolored, giving the effect in changing light conditions of a mysterious irridescence. It came to England from Japan sometime after the Second World War, and was in a private collection until the museum acquired it by purchase in 1979. The later box dates to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, and is inlaid in mother-of-pearl with scrolling lotus flowers and foliage (pl. 14). It was probably made to contain clothing-perhaps a priest's vest merits. Its interior is lacquered red, and its base—as is usual with Korean boxes of this kind—is plain unlacquered wood.

Among the non-ceramic items in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum is a Koryo dynasty bronze flower vase with inlaid silver decoration (pl. 17). The shape of this rare bottle is evidently closely related to that of its ceramic contemporaries of the twelfth to thirteenth century and especially to Koryo celadons of the twelfth century. Indeed, there is in the collection of Godfrey Gompertz (now housed at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) a celadon vase which closely resembles this bronze in both shape and size. The simple linear decoration of this bronze has also its ceramic counterpart in some of the inlaid Koryo celadons. The purpose of this and similar bronze vessels is not known for certain, but it was probably made for use as a flower vase in a Buddhist temple.

Turning to Korean paintings, the British Museum once again holds the finest examples in the United Kingdom. The fifteenth-century Kwanum in White Robes is a rare example of Buddhist painting from the first century of the Yi dynasty, when Buddhism often suffered from the proscriptions of the new Confucian court (pl. 18). During the Koryo dynasty, the bodhisattva Kwanum (Sanskrit, 'Avalokiteshvara') had appeared frequently as an accompanying figure in depictions of Amitabha, or as the 7. Pak, Korea: Korean Days, pp. 50-51. (6-2, p. 15) main figure of 'Water :Moon Avalokiteshvara' paintings. He is identified by-the kalasha (flask) he holds, as well as by his white robes. In most representations, Kwanum wears the Dhyani Buddha (Buddha of Purity, Meditation, and Enlightenment) in his crown; here, this has been replaced by a miniature Amitabha triad, symbolic of the Buddha's descent to receive the soul of a believer. The final triumph of Yi dynasty Neo-Confucianism over Buddhism is also reflected in the British Museum's portrait of a Confucian scholar, which dates to the eighteenth or nineteenth century (pl. 19). Executed in ink and light color, this portrait reflects both the stylistic influences at work in Yi dynasty Korea, and the changing ethics of its society. The otherworldly appeal of the Western Paradise is here replaced by the canny realism of the literati, as surely as the monk of the Koryo dynasty was replaced by the scholar-bureaucrat of the Yi dynasty.

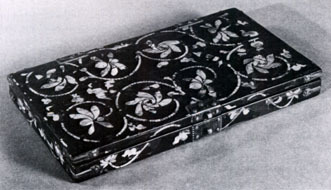

In Private Hands 'With Godfrey Gompertz' splendid donation of his entire collection to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, it must be assumed that comparatively few Korean works of distinction now remain in private hands in the United Kingdom. Two examples from a private collection are however illustrated here: a Koryo celadon bottle vase of simple form, and a lacquer box of unusual shape with inlaid mother-of-pearl decoration of peony scrolls (pls. 20, 21). The celadon wine bottle dates from the middle of the twelfth century, and has a pear-shaped body and flared neck (pl. 20). It is obvious that the early Koryo potters were greatly influenced by Chinese wares-in particular by the Yue (Yueh) celadons of the Northern Song dynasty-but also by-the lovely plain bluish-green glazed official wares called Ru (Ju) wares. This graceful Koryo wine bottle with its undecorated bluish-green celadon glaze is an example of such influence. It is in fact almost identical in shape and appearance to a famous Ru ware bottle formerly in the Alfred Clark collection and now in the British Museum—the only marked difference being the more lavender tone of the RU glaze. The mouth of this piece has been repaired in gold lacquer. The shallow hinged lacquer box illustrated here is an example of a type not uncommon among mother-of-pearl inlaid lacquer wares of the Yi dynasty (pl. 21). Its bold decoration of peony scrolls, which includes a number of birds in flight, suggests that it is (6-2, p. 16) early-probably dating from the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. The late Sir Harry Garner, who much admired this box, considered that it probably belonged to the fifteenth century. The metal fittings with strengthening corner-pieces terminating in rosettes, are of a type commonly found in Korean boxes.

Sir John Figgess is a noted collector and expert in Korean ceramics, who has studied the collections of Korean works of art in museums throughout the world, and has explored extensively the stylistic connections between the techniques of inlaid lacquerware and celadons o1 the Koryo dynasty. 1. The collection of the Freer Gallery of Art includes a similar, but smaller, celadon kundika, also with inlaid slip decoration; a photograph of this piece was published by Ann Yonemura, "Korean Art in the Freer Gallery of Art [Korean Art in Western Collections: 5]," Korean Culture 4:2 (June 1980), pl. 6.

|

| Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles |

|

3-4, p. 4)

Marjorie L. Williams

(3-4, p. 5) Brilliantly-colored icons, greenhued celadons, and brightly-painted oxhorn boxes all highlight the collection of Korean art at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Almost as old as this institution itself, which opened its doors to the public in 1916, the Korean collection began in 1918 with gifts of a Koryo dynasty (1918-1392) bronze trinity (pl. 3) from the Worcester R. Warner Collection and a celadon bowl (pl. 6) of the same era from the John L. Severance Collection. During the following six decades the collection has grown through the gracious assistance of museum patrons, such as Severance and Greta Millikin and J. H. Wade, and the discriminating connoisseurship of the museum directors, William M. Milliken and Sherman E. Lee. The unique assemblage of Korean ceramics is due in large part to John L. Severance, a patron of both the visual and musical arts in Cleveland. As a contributor to both the Western and Eastern collections, Mr. Severance donated approximately two hundred Korean ceramics from the family's collection. This well-known figure in the Cleveland art-world had a particular affinity for Korean art since his father, a noted Cleveland physician, established the Severance Medical School and Hospital in Seoul, Korea. Even after his death in 1936, the John L. Severance Fund enabled the museum to acquire additional masterpieces of Korean art. The Cleveland Museum displays masterpieces of both ceramics and painting found in few other Western collections. The ceramics collection is a comprehensive one illustrating, in particular, the development of the stoneware tradition that dominated the historic evolution of Korean ceramics. To this already significant holding the museum has added, in only the last three years, four paintings — two rare Buddhist paintings dating from the Koryo dynasty and two hanging scrolls of secular themes completed during the later Yi dynasty (1392-1910) — to make the Cleveland Museum of Art an important collection for the study of Korean painting. (3-4, p. 6)

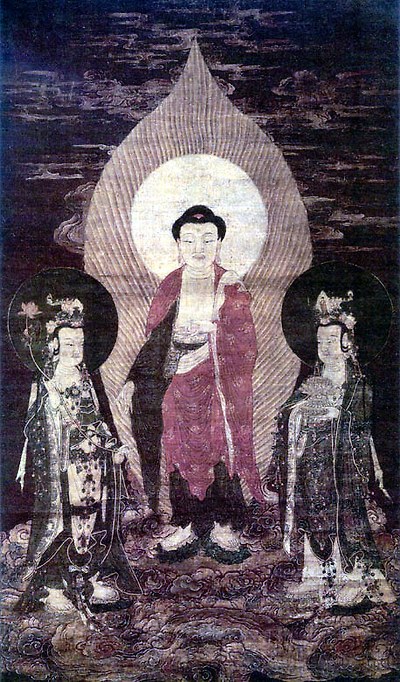

Buddhism, the unifying religion of the East, entered Korea during the fourth century and continued to dominate the lives of the aristocracy and commoners alike throughout the following thousand years. These foreign doctrines inspired the kings of the Silla dynasty (668-918) to construct large temples such as Pulguk-sa and the magnificent mountainous shrine, the Sokkuram. Kings of the later Koryo dynasty designated separate offices within the court, called the Institute of Gold Letters and Silver Letters (Kumja-won and Unja-won), in which monks copied the Buddhist sutras, or scriptures. Although the Koryo rulers basically continued the grand traditions of Buddhism established during the preceding centuries, they introduced a new element to its doctrines and arts. The late Koryo kings established close ties with China and its foreign Mongol rulers who patronized Tibetan Lamaism. By the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries Lamaistic doctrines had entered the court circles, thereby introducing a highly decorative flair to the Buddhist arts. The three Buddhist trinities (pls. 1-3) in the Cleveland collection all attest to this elegant style which characterizes sculptures and paintings created during the late Koryo dynasty. Entering the Cleveland Museum in 1961, the Amitabha Triad (pl. 1 ) — painted around 1250 — exemplifies the majority of extant Koryo Buddhist paintings that illustrate scenes of the Pure Land Sect of Buddhism. This sect, which originated in India and developed more fully in China, gained widespread popularity throughout the East because it provided an easy path to salvation. The devotee was assured, through simple faith and the mere recitation of Amitabha's name, a rebirth into Amitabha's Western Paradise. In the Korean hanging scroll, Amitabha — standing in front of a flaming mandorla — occupies the center of the trinity. In accordance with the iconography of this deity, he is attended by the bodhisattvas Mahasthamaprapta — positioned at his right and identified by the water jar in his headdress — and Avalokiteshvara — standing at his left and identified by the image of the Shakyamuni Buddha accenting his headdress. Amitabha's left hand — posed in a variation of the vitarka mudra — and the lotus throne carried by Avalokiteshvara suggest the theme of the painting, most commonly known by its Japanese designation, raigo, 'Welcoming Descent.' A common theme in Pure Land Buddhism, the raigo illustrates the moment when Amitabha appears at the deathbed of a faithful follower to welcome his soul into the Western Paradise. Avalokiteshvara, the God of Mercy, carries the soul of his devotee on the lotus seat to the land of unimaginable beauty. Unlike most raigos, in which both Mahasthamaprapta and Avalokiteshvara bow toward the viewer extending an invitation into the ideal world, however, this Korean painting depicts the trinity in a more formal, hieratic fashion. The three figures are rendered in an elegant, decorative style most obvious in the bodhisattva's jewelry and Amitabha's robe enriched with gold medallions. The refined, linear brushwork, evident to a seemingly excessive degree in Amitabha's garments and the mandorla, enhances this decorative quality introduced into Korean Buddhist arts through the lavishly ornamented accessories of Tibetan Lamaism.

The large icon, Shakyamuni and Two Attendants (cover and pl. 2), completed around 1300 and added to the Cleveland collection only this year, echoes the same decorative style preval!ent in Koryo Buddhist arts by the late thirteenth century. The large scale of the icon, achieved by joining vertically three strips of silk cloth, suggests that it originally hung in an important, metropolitan temple. Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, sits in a large, hexagonal throne ornamented with lotus motifs and a recumbent (3-4, p. 7) lion (a protector of the Buddhist faith) encircled by flaming pearls (a symbol of purity representing Buddha's truth). His symmetrically rendered features — including his nose distinctively outlined by two vertical lines connecting with the arched eyebrows — recall the similar detailing of Amitabha's features (pl. 1 ). The deity's right hand, positioned in the mudra usually known by its Japanese name, kichijo-in, grants good fortune to the two adoring, priestly attendants who complete the frontal, symmetrical icon. Brilliantly colored with an intense red, malachite green, and azurite blue, and extraordinarily preserved, this masterpiece and the Amitabha Triad parallel in both style and date the famous painting depicting Avalokiteshvara with a Willow Branch, completed in 1313 by the Korean master Hyeho and presently in the Senso-ji Temple in Japan. A copy of the Korean trinity by the Japanese painter Jakuchi (1716-1800) is a part of the collection of the Shokoku-ji in Kyoto, Japan. Although Shakyamuni is generally depicted with his attendant bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara and Maitreya, the bronze Shakyamuni Trinity (pl. 3) departs from this usual iconographic representation. All three deities sit on individual lotus thrones; Shakyamuni with his right hand expressing the vitarka or 'teaching' mudra sits in crosslegged fashion, while his attendants sit in the more relaxed, lalitasana pose with one leg pendant and the other bent at the knee. Avalokiteshvara, identified by the seated Buddha image in his crown, sits at his left while Kshitigarbha, holding the sacred jewel, sits at his right. This deity, commonly known by his Japanese name, Jizo, is represented with shaven head in the guise of a monk. The idealized proportions of the deities' faces and the sharp curves of their eyebrows and noses — coupled with the beaded jewelry accenting their necks, knees, and lotus seats — suggest that the triptych is a creation of the late thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries. Bodhisattvas, or enlightened beings (such as Avalokiteshvara), who delay the state of their Buddhahood to become teachers of Buddhist doctrines, are the most essential deities in the East Asian Buddhist pantheon, and are commonly represented in Korean art. In contrast, nahans (Chinese, 'lohans') or Buddhist disciples, hold a lesser position in northern Buddhist doctrines and iconography and appear less (3-4, p. 8) frequently in Korean art. Depicted as wizened, mystical men, nahans are occasionally represented alone but more frequently encountered in groups of sixteen, eighteen, or crowds of five hundred.

This Korean nahan, seated in profile view, is distinctively Indian in appearance. Subtle tones of ink model his face, and his gnarled arm extends an alms bowl to a writhing dragon, a protector of the Buddhist faith. The partially visible inscription in the upper right corner reads "464 [?] nahan" while the names of the donors are written at the lower edge. Customarily an individual donor commissioned a single nahan painting while a group of worshippers commissioned a set of sixteen, eighteen, or, in this case, five hundred.

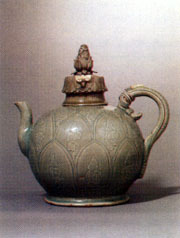

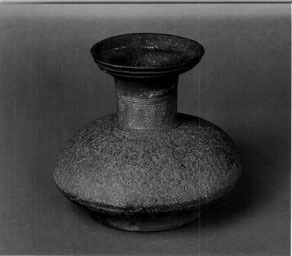

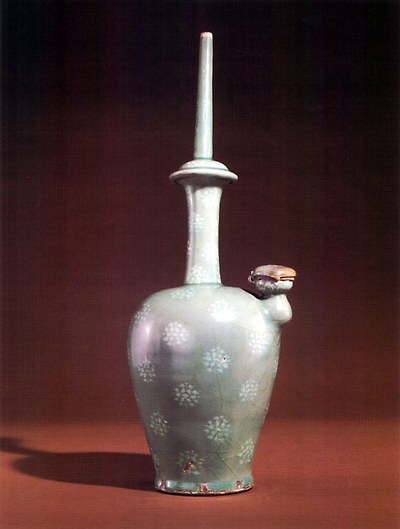

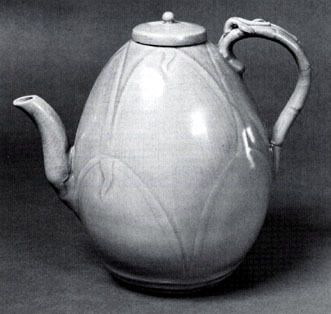

Of all the Korean arts, ceramics, by virtue of their functional nature, are the most easily understood by Western museum visitors. The casual visitor immediately knows when looking at the covered bowl (pl. 5) or the Ewer in Form of a Sprouting Bamboo (pl. 10) that they served food and wine because their shapes demonstrate their original (3-4, p. 9) functions. This bowl and ewer represent the climactic stage of the long stoneware tradition characterizing Korean art. Produced as early as the first century A.D. in southern Korea, stoneware ceramics are impervious to liquids when fashioned from clay fired at temperatures of 1200-1300 degrees centigrade. This tradition, culminating in the green-glazed celadon of the Koryo dynasty, continued to be the foundation of Korean ceramic history throughout the following centuries.

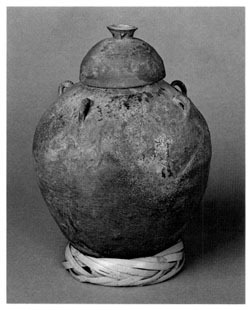

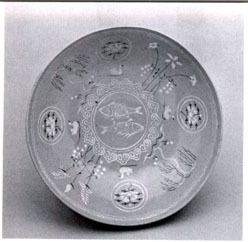

The covered bowl with stamped decorations (pl. 5), dating from the eighth and ninth centuries, represents the earliest type of stoneware produced during the Silla kingdom (668-918) near the city of Kyong-ju. Wheel-thrown, the bowl typifies the early ceramics created from a dark, grayish-black clay found in this region. The decorations accenting these early ceramics were simple and direct; geometric or floral patterns were either incised or stamped directly onto the clay body. In contrast, slight glazing discernible on the bowl was not an intentional element of the decorative scheme but was a purely accidental addition of the firing process. Ash from the wood used to fuel the kiln settled in the heated clay, uniting with iron impurities to form drops of glass on the bowl's surface. Admired by both Chinese scholars and Korean kings, Korean celadons dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries of the Koryo dynasty represent the crowning achievement of Korean potters. The three celadon ceramics — the bowl (pl. 6), kundika (pl. 7), and vase (pl. 8) — all typify the early stages of this industry when Korean potters were influenced by Chinese celadons and porcelains brought to Korea by merchant ships or official envoys. These wares are identified by their blue-green color, the result of small quantities of iron present in the glaze mixture that turns green during a reduction firing (when all the oxygen is removed from the kiln). The Chinese called this coveted color bi-se, 'the secret color,' while Korean poets compared it to the color of the autumn skies or the blue-green feathers of the kingfisher bird. (3-4, p. 10)

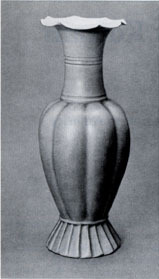

Historical records document political ties between this state and the Koryo kingdom. In 924 and 925 Chinese envoys sailed from the nearby port city of Ning-p'o to the Koryo capital Kaesong. Examples of the Chinese Yueh bowls were no doubt taken to Korea as official gifts since the penchant for fine ceramics, shared by all Korean rulers, was well-known in China. Once in Korea, the bowls inspired the native Korean potters who 'Koreanized' the Chinese phoenix motif so that it resembled a parrot. Although wispy incised birds commonly accent eleventh and twelfth-century celadon bowls, they are rarely, if ever, seen highlighting the body of a kundika (pl. 7) of similar date. The unique combination of this particular motif and shape introduces a masterpiece of Korean art in the Cleveland collection. The kundika, or holy water sprinkler, is an essential element of Buddhist liturgy and iconography. This ritual water container is identified by the tall pointed spout for pouring or sprinkling water, and the smaller one, capped and cupshaped, for filling the hollow interior. Although the shape, introduced to Korea from China, and derived ultimately from India, is a common one among Far Eastern countries, Korean craftsmen in particular fashioned numerous examples of this accessory of worship during the Koryo Dynasty. The kundika, created from either metal or ceramic, reflects the dominance of the Buddhist faith during this period. As early as the fifth and sixth centuries, ceramics were considered important furnishings for a royal tomb. This desire to surround the deceased ruler with earthly riches continued into the Koryo dynasty when the greenhued celadons served as mortuary gifts. The lobed vase (pl. 8) in the Cleveland Museum recalls a similar vase excavated from the tomb of King Injong (reigned 1123-1146). The shape with pleated foot, lobed body resembling a melon, and a flaring rim probably originated in Chinese Qing-bai (Ch'ing-pai) porcelains. Examples of similar Qing-bai vases, found near aristocratic tombs located near Kaesong, are presently housed in the National Museum of Korea located in Seoul. (3-4, p. 11)

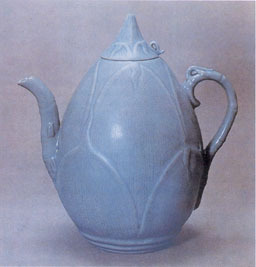

By the twelfth century, Korean potters had established an independence from the Chinese ceramic industry by developing unique sculpturesque shapes and ceramic techniques. This phase of Koryo celadons is further illustrated at the Cleveland Museum through the Ewer in Form of Sprouting Bamboo (3-4, p. 12) (pl. 10) and the lid for a box (pl. 11). Korean potters ingeniously integrated botanical motifs into ceramic forms so as to create a unique union of decoration and shape. The delicately incised and veined leaves accenting the swelling profile of the wine ewer recalls a young bamboo shoot with overlapping sheaths. The decorative scheme extends even to the segmented, notched handle that resembles a mature bamboo stalk. Swirling cranes, a traditional symbol of immortality, and stylized chrysanthemums enliven the lid of a circular cosmetic box (pl. 11). Although the decorative techniques of incising and stamping were widely used by Chinese and Japanese potters, inlaying motifs with white or black clay slips was a unique innovation of Korean potters. Originating during the reign of King Uijong (reigned 1147-1170), who was scorned by Korean scholars of succeeding centuries for his hedonistic life-style and extravagant building campaigns, this decorative technique takes those other, more common techniques of incising and stamping to their ultimate conclusion. If left untouched, those incised, recessed decorations such as the flying parrots (see pl. 6) would be subtly highlighted by the pooling of the green celadon glaze. The innovative potters simply filled in the intaglio designs incised or carved out of the clay body with colored slips. Most ceramicists today agree that these inlaid celadons received two firings: an initial, low-temperature one after the completion of the inlay process, and a final, high-temperature firing after glazing the wares. The flat surface of the ceramic lid with intricate motifs orderly arranged in a medallion-like design resembles a richly-embroidered tapestry. Korean potters extended the traditional limits of the ceramic medium so it resembled other artistic media sharing similar motifs. The maebyong vase (p1. 12), dating from the twelfth century, introduces one of the most common shapes observed in Korean ceramics. Originating in China where it is called the mei-bing or 'prunus vase,' the form is distinguished by a small neck opening, broad, bulging shoulders — emphasized by the constricted lower half — and a flaring base. This particular maebyong exemplifies a rare type of stoneware with underglaze black slip. Produced at the Sadang-ni kiln sites in South Cholla Province, the ware's affinity to celadon is obvious through its iron-bearing glaze and the inlay decorative technique. The vine motif accenting the rounded shoulders was incised into the body after coating it with a dark slip. The potter then carved away the black slip and filled-in the intaglio design with white slip. Existing in numerous examples, the vase shape probably functioned as a container for storing or serving wine and water.

A white glaze freely painted over the dark clay body is a common feature of both these ceramics and a distinguishing characteristic of all punch'ong stoneware. Using a variety of decorative techniques, potters manipulated this slip to create diverse decorations. The entire surface of the pear-shaped wine bottle, for example, was first coated with a clay slip having the consistency of heavy cream. Motifs of fish and water foliage and stylized lotus leaves were next drawn onto the slip.

In contrast, the decorative scheme of the placenta jar with four 'ears,' or handles, is more complex. It combines the inlay technique — inherited from the Koryo celadon tradition — with the more spontaneous decorations typical of punch'ong ware. The potter thoughtfully divided the surface of the bold jar into three concentric bands of decoration. Using a serrated tool, he stamped into the clay slip covering the shoulder the 'rope-curtain' pattern. The combination of these two techniques suggests that the jar was a creation of the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century — the transitional period between the refined inlaid celadons and the coarser punch'ong wares. The jar reflects both innovative pottery techniques and traditional folk practices. The afterbirth of a child was buried in these large jars to grant its future happiness. (3-4, p. 13)

(3-4, p. 14)

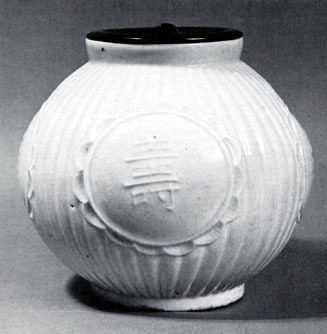

The porcelain Jar with Relief Design of Four Characters (pl. 15) is the most recent acquisition to the Cleveland collection of Korean ceramics. Sometime after its creation in the eighteenth century, the jar was taken to Japan where it served as a mizusashi, or cold water jar, in a tea ceremony. The black lacquer lid was, no doubt, added to the jar at this time. Although porcelains were created as early as the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the coveted celadons overshadowed their simple, unobtrusive beauty. This white ware produced from the high-fired kaolin-rich clay was not patronized by Korea's ruling communities until the Yi dynasty. It then became the official ceramic ware of this era ruled by Confucian kings and scholars. Unlike many Yi dynasty porcelains painted with underglaze blue decorative themes, this mel-on-shaped jar consists of molded designs expressing wishes for a prosperous life. The four molded characters su, neung, kang, bok (long life, safety, health, and happiness) accent the floral medallions. Created at the height of Korean porcelains, the thickly potted jar is thought to be a product of the Punwon-ri kilns located in the area of Kwangju, Kyonggi-do. If Buddhist monks and painted or sculpted icons distinguish the Koryo dynasty, the scholar-official and the arts of painting and calligraphy characterize the following Yi dynasty. The late fourteenth century witnessed the downfall of the (3-4, p. 15) Buddhist aristocracy and the ascent of Neo-Confucian rulers and scholars. During this five-hundred-year period, the art of painting rose to a respected position equal to that traditionally held by the ceramic arts. Fifteenth-century Korean kings followed the examples of earlier, twelfth-century Chinese emperors by establishing a Bureau of Painting (Tohwa-so) at the court. The professional artists who were members of this academy continued the Chinese classical styles of painting established in that neighboring country during the earlier eleventh and twelfth centuries.

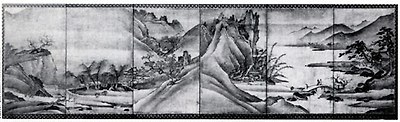

Congenial relations between Korea and its neighbors during the fifteenth century afforded Korean artists the opportunity to travel to both the mainland and to Japan where a school of ink painting was developed within the Zen monasteries in Kyoto. Yi Su-min is just one of the artists who made the journey from Korea to Japan during this century. Although none of his works remain in Korea, an album of his bamboo paintings exists in a private collection in Japan and a pair of his folding screens (pl. 16) can be observed at the Cleveland Museum of Art. An autobiographical note inscribed on his bamboo album establishes that Yi Su-min was in Japan by 1425. Although very little is known about this enigmatic figure, it is possible that he traveled to Japan with the Japanese priest-painter Shubun who had visited Korea as part of an official envoy one year earlier in 1423-24. It is speculated that Yi Su-min returned to Japan with this artist, who is considered to be one of the founders of the Japanese school of ink-painting ultimately based on Chinese painting styles. Once in Japan, Yi Su-min became an established artist, patronized by the Asakura family, and the founder of the Saga school of painters centered around the Daitoku-ji monastery in Kyoto. The Landscapes of Four Seasons (pl. 16) in the Cleveland Museum is the only work by this artist, also known by his Japanese name Ri Shubun, in the Western world. The landscape scenes follow the usual format for representing seasonal themes in screen paintings. The Winter and Summer scenes appear at the end panels while the gentler Fall and Spring seasons join where the folding screens meet. The screens recall the composition of thirteenth-century Southern Sung Chinese handscrolls where fragments of land, located 'near' the viewer at the lower edge, are complemented by receding mountainous forms on the other or 'far' side of the river. Using only limited brush techniques Yi Su-min simplified the mountains and travelers to angular brushstrokes and subtly graded washes. (3-4, p. 16)

In 1979, the Cleveland Museum acquired another fifteenth-century Korean landscape painting (pl. 17). The carefully rendered hanging scroll represents a Buddhist temple in a mountainous landscape. The (3-4, p. 17) monumental, rocky forms — outlined with dark ink and modeled with graded washes and staccatolike strokes — dominate the painting composition at the left and are sharply contrasted by a river valley — created primarily from soft ink washes — receding at the right of the painting. The viewer's eyes are drawn to the temple at the top of the mountain silhouetted by a distant, misty gulf. The juxtaposition of the mountain and river views plus this isolation of one particular vantage point in the upper half of the scroll recalls the 'high distance' compositions typical of earlier eleventh-and twelfth-century Chinese painting.

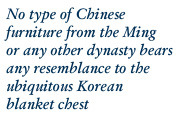

This particular portrait of a stout, affable anonymous official typifies most Yi dynasty portraits based on Chinese imperial portraits. The official is seated in a formal, frontal pose. The head of a tiger skin, draped over his chair, is visible near the gentleman's shoes. Although the artist attempted to individualize his model's physical features, the portrait accomplishes — through insignias of rank — its true intent: to convey the social status and court position of the official. The breast plate embroidered with flying cranes and the winged, silk sano hat indicates this man of large stature was one of the three highest-ranking ministers at court. No collection of Korean art is complete without at least one example of the traditional folk crafts created by Yi dynasty artisans. The nineteenth-century storage chest (pl. 19) is a superior example of the hwagak, or oxhorn boxes, representing a craft unique to Korean art. Pieces of oxhorn — flattened through a soaking and heating process — were glued onto the wooden core of the chest. The colorful animal and floral designs set against a yellow ground were painted on the underside of the horn so their bright forms are visible through the thin, transparent sheet. The decorations introduce the themes of traditional folk paintings generally hung in Korean homes for good omen. The dragon protects the family, the tiger ensures good luck, and the deer with the tree-like lichen extends wishes for a long life. Including both the aloof icons of the Buddhist faith and the familiar symbols of folk beliefs, the Cleveland Museum of Art introduces to its museum visitors some of the finest achievements of Korean art. Marjorie L. Williams is an assistant curator in the Department of Art History and Education at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

|

| Korean Cultural Center, Los Angeles |

3-3, p. 4)

George Kuwayama

|

|

(3-3, p. 5)

Of the major ceramic traditions of East Asia, Korean ceramics are the least known. Since the mid sixteenth century, the palaces of Europe have been embellished with Chinese porcelains; while Japanese Kakiemon and Imari bottles, covered jars, and figurines have long adorned the chambers of European castles. By contrast, it has been only within the twentieth century that Korean ceramics have come to be admired in the West.

The first Korean wares to enter an American museum collection arrived at the Smithsonian in Washington in 1891. During the first two decades of this century European and American collections of Korean ceramics grew enormously, with wares of the Koryo dynasty (918-1392) obtained from the royal tombs around the ancient capital of Kaesong and from the island of Kanghwa in the Han River estuary. In 1918, Bernard Rackham, the Keeper of Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, wrote admiringly of Korean wares in his Catalog of the LeBlond Collection of Corean Pottery. Among these wares, Rackham mentioned porcellaneous celadons as being "the most characteristic of all Korean wares and in their finest manifestation the most beautiful." Rackham's successor at the Victoria and Albert, W. B. Honey, wrote in 1945 that Koryo celadons were "one of the summits of all ceramic achievement." In recent decades American museums have slowly acquired some excellent examples of Korean ceramics, ranging in date from the Old Silla period through to the Yi dynasty.

Although the West has been slow to appreciate them, Koryo celadons have been ardently admired in the Far East since as early as the twelfth century. Xu Jing (Hsu Ching), a young Chinese official renowned for his calligraphy, accompanied the Chinese emissary to the Koryo court in 1123. In the following year he wrote a detailed account of his travels, with illustrations, entitled Xuan-he Feng Shi Gao-li Tu-jing (Hsuan-ho Feng Shih Kao-li Tu-ching). Although the original illustrated copy of this text was lost when the Chin Tartars invaded north China in 1126, a Song dynasty printed edition without illustrations remains, and is currently preserved in the Palace Museum, Taipei. The Gao-li Tu-jing is a comprehensive account (in forty chapters, comprising some three hundred headings) of Korean customs and institutions, with a brief but informative section on 'wares and vessels' in which Xu Jing gives high praise to Koryo celadons. He was particularly impressed by the (3-3, p. 6) wine pots and incense burners, because their novel design and glaze color resembled "the old bi-se (secret color) of Yueh and the new wares from the Ru kilns." For a Chinese official to admit that anything matched the beauty of Imperial Ru wares would have been an extreme compliment, indeed.

|

Celadons are high fired stonewares, during the making of which kiln temperatures reach 1,300 degrees centigrade. Their light grey or buff colored bodies are covered with a transparent feld-spathic glaze containing traces of iron that turn blue-green when fired under reduction conditions (that is, without air), and brown when combined with the oxygen of the atmosphere. Oddly, the word celadon is not a Chinese or Korean term at all, but French. It derives from an otherwise undistinguished |

Of all the Korean celadons, ceramic connoisseurs consider those of the Koryo period most attractive, because of the beauty of their form. Curved contours — without jagged angles or rigid, straight lines — provide Koryo celadons with a graceful silhouette, while their flowing lines and subtle curves suggest freedom and strength. The coloration of Koryo celadons ranges from a subdued greyish-to-bluish green to an exquisite light green, infinitely rich in its subtle variations of tone and lustrous, opalescent depth. Their incised and carved decorations are executed with great flair and finesse, while molded or impressed patterns — essentially mechanical in technique — appear free and spontaneous. These celadons Also display the greatest innovation of the Korean potter: the use of black and white inlaid designs under the glaze. The overall feeling imparted by these celadons is one of endless tranquillity evoked without pretension, in a mood of peaceful solitude.

|

Influences and Origins The foundations of the Koryo ceramic industry were laid in the ceramic technology of the high fired stonewares and glazed ceramics of the preceding Unified Silla period (668-935. The ceramic wares of China, however, also stimulated the development of Koryo celadons, which reveal their indebtedness to Chinese prototypes in their glazes, shapes, decorative techniques, and motifs. |

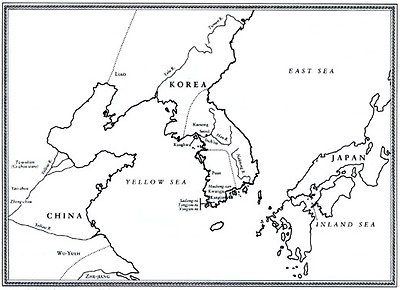

In China, ash-glazed proto-celadons were produced at Zheng-chou (Cheng-chou) as early as the middle Shang dynasty, about 1400 B.C. However, fully developed celadons have only been made in China since about the third century A.D. at the Yueh kilns in Zhe-jiang (Che-chiang) province. These Yueh kilns, which could be reached easily by sea from the south-west coast of Korea, provided an important source of ceramic techniques. In later centuries, these influences were accompanied by other contacts between the regions: the Chinese state of Wu-Yueh [in the provinces of Zhe-jiang [Che-chiang] and Jiang-su [Chiang-su] and the Koryo dynasty were both Buddhist states with frequent cultural and religious exchanges.

|

Korea and China, showing principal kiln sites. |

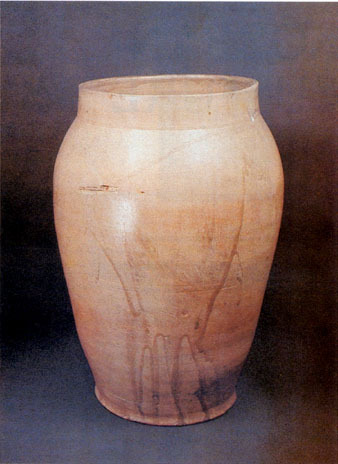

Toward the end of the Unified Sil-(3-3, p. 7)la period, north China provided still another source of ceramic technology. Northern Chinese kilns had already begun to produce high fired wares, and may have assisted in establishing kilns at Inch'on and at other sites along the west coast of Korea. Some evidence for this northern Chinese influence has been unearthed in recent decades. In 1964, during the construction of the Seaside Golf Club at Inch'on, pottery sherds of an early type of celadon ware were found. The sherds were brownish in color due to oxidation, and were often incompletely fused because of underfiring (pl. 1).* Together with these sherds were found the remains of several kilns, built on a slope which extended about twenty-five to thirty feet. The early date of the Seaside site is suggested by the fact that the kilns discovered there lack the partitions characteristic of all kilns of the Koryo period. Further, the remains of only five kilns were found, indicating that this ceramic center had a short life. Like many ancient kiln sites in Korea, this site is near to the sea so as to facilitate transport by boat. Examination of the sherds by Korean archeologists reveal stylistic analogies with ninthand tenth-century wares of the late Tang and Five Dynasties period in northern China. It may be surmised that an incipient form of celadon began to be produced at the Seaside site early in the tenth century. Since this discovery, several similar kiln sites have been discovered up and down the Yellow Sea coastline from Inch'on.

Early Koryo Celadons

The earliest dated Koryo vessel is a wide-mouthed jar, now in the collection of Ehwa Women's University, which bears an inscription stating that it was made for the ancestral shrine commemorating the founder of the dynasty (pl. 2). The Koryo-sa (History of Koryo) records that this shrine was begun in 989 and completed in 993, confirm!ing the inscription on the jar. This vessel represents one of the early efforts to produce high fired stoneware with feldspathic glaze in Korea. It is essentially a white ware with a primitive glaze, and its simple form — with straight mouth and slightly splayed foot-rim — derives from Chinese prototypes.

During the eleventh century, and particularly during the peaceful and prosperous reign of King Munjong (1047-1083), rapid strides were made toward the production (3-3, p. 8) of fine celadons. Chinese Song wares were import!ed by Korea, in a flourishing reciprocal trade that inspired high levels of achievement. The elegant forms and subtle potting of white Ding (Ting) and Qingbai (Ch'ing-pai) wares acted as models for early Koryo vases. By the end of the eleventh century, the celadons of Ding, Qing-bai, and Yao-zhou (Yao-chou) — that is, the wares of northern China — were also the dominant influences for carved and molded decorations. Ding was the main inspiration for carved and incised wares, while molded designs were derived equally from Ding and Yao-zhou. Some of the painted designs used during this period may owe their origins to the influence of wares from Ci-zhou (Ts'u-chou); however, designs painted in white slip on a black ground, and then glazed with celadon, reflect a development that is uniquely Korean.

In addition to Chinese influences, wares from Liao — a state to the north of Korea inhabited by Khitan peoples — provided another important stimulus to the development of Koryo celadons. Although Liao was strongly sinicized, it also maintained a culture and style of its own. Liao vases with long, narrow necks and dish-shaped mouths appealed to the Koryo potter, and the angularity of the upper portions of these vases formed a pleasing contrast to the rounded contours of the body. Liao influences are evident in the designs of floral arabesques on Koryo wares, as well as in Koryo ewers with pronounced shoulders. The thin, sinuous, elongated dragon inlaid on Koryo vases also derives from Liao, and is visibly distinct from the full, rounded, scaled bodies characteristic of Chinese dragons. The influence of Liao on Koryo pottery is partly explained by the Koryo-sa, which reports that the Jurchen Tartars revolted against their Khitan rulers between 1115 and 1117, and that as a result hordes of Khitan refugees streamed into Korea. A few years later, Xu Jing's report on his Korean trip states that "there were many thousands of Khitan [that is, Liao] captives of whom one in ten was a craftsman."

Maturity and Invention

The second phase in the development of Koryo celadons occurred during the twelfth century, when the Korean potter had mastered his craft and began experimenting with new forms, techniques, and designs. This was the apogee in the development of Koryo celadons, with production centered at Kangjin and Puan. The ceramic vessels created during this period are unsurpassed for their elegant shapes, exquisite glazes, and superb artistry.

In 1914, archeologists discovered a large kiln complex at Kangjin on the southwestern tip of the Korean peninsula. This kiln site had been active from the tenth through the thirteenth centuries, and by the mid twelfth century incomparable celadons were being produced there. Many Kangjin pieces were covered with the fabled Kingfisher blue glaze, decorated with incised or impressed designs, and inlaid or painted with slip. Early Kangjin wares, such as the sherds excavated from Yongun-ni kiln number eleven, datable to the eleventh century, owe their inspiration to the Yueh wares of Zhe-jiang province. In view of the history of sea-links and other close relationships between Zhe-jiang and southernmost Korea, it is conceivable that Chinese potters emigrated and settled in southern Korea, and assisted in the establishment of the Kangjin kilns. The earliest of these kilns were built during the tenth century at the end of a steep valley; subsequent kilns were constructed lower down in the valley, with the result that by the twelfth century the kilns were close to the shore. Early Kangjin wares were roughly potted, with a dull, grey-green glaze or a glaze that had turned light brown due to oxidation. The highly splayed foot-ring, and the flat, wide foot-rim found in early Kangjin wares are both characteristic of Chinese Yueh wares, as are also the large white clay spurmarks made by kiln supports; all of these suggest the influence of Chinese potters. Interestingly, there is a celadon bottle from Kangjin in the National Museum of Korea that bears the date 1049 (pl. 3).

Some of the finest extant Kangjin wares are those which came from the village of Sadang-ni, a twelfth-century kiln site that received the patronage of the Koryo court. The significance of findings that have been made at Sadang-ni was slow to be realized: although fragments of celadon roof tiles were discovered in the Kangjin kiln area in 1914, these received little further attention. In June of 1928, several small celadon roof-tile fragments ornamented with floral arabesques in relief were found at the site of Sadang-ni kiln number seven. Together with these, many other ceramic sherds of the finest quality were uncovered, adorned with underglaze incising and slip inlay. Two months later, fragments of both round and flat celadon roof tiles were found at Manwol-tai, the site of the Koryo royal palace in Kaesong. The Koryo-sa records that the epicurean King Uijong commissioned the construction of a Summer palace in 1157. The pavilions were filled with rare and precious objects, the grounds were landscaped with plants and flowers, and an artificial lake was made within the palace grounds. On the northern section of the palace grounds the Yang-i-jong pavilion was constructed, and celadon tiles were used for the roof. The discoveries of 1928 did not exhaust the available sites, by any means. In 1964, celadon-glazed roof tiles with molded decoration were excavated at Tangjon-ni in the Kangjin area; these tiles are now preserved in the National Museum of Korea (pl. 4). In these examples, the round end tiles depict in relief a peony twig within double circles and bordering dots. Between the circular end tiles are the slabs of concave roof tiles, embellished at their outer edge with an elegant floral arabesque handsomely rendered in relief. These designs are crisply molded and thickly glazed with greyishgreen celadon. The tiles reflect the (3-3, p. 10) sumptuous elegance and refined tastes of the aristocratic Koryo court.

Puan was another twelfth-century ceramic center that produced some of the finest Koryo celadons, and received the patronage of the court. Puan was established a little later than Kangjin, and was particularly noted for its fine inlaid celadons.

(3-3, p. 9)

|

|

|

Korean Form and Style

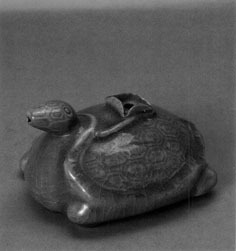

There is an essentially Korean character to the form and style of twelfth-century Koryo wares. When a shape was borrowed from China, it was inevitably modified to suit Korean aesthetic sensibilities. Koryo celadon vessels were often used in rituals, and the traditionalism of Koreans may be observed in vessels that copy and continue the archaic bronze ritualforms of ancient China. The Ding tripod in the National Museum of Korea, for example, is typically Sino-Korean, with its relief design of a tao-tieh monster mask, vertical flanges, horizontal grooves, and spiral ground (pl. 5); but there is also a typically Korean whimsy in the rendering of the zoomorphic beasts. Among the most popular forms of Koryo celadons are the wine pots and incense burners. Xu Jing, the Chinese diplomat who visited Korea in 1123, was enormously impressed by these shapes, and mentions that they were frequently surmounted by ducks, lions, or mythical beasts modeled in the round. The National Museum of Korea has an incense burner with a lion-shaped cover that closely matches Xu Jing's description (pl. 6). Reflecting Buddhist tradition, this incense burner depicts a male lion holding a ball; carved, incised, and appliqued details enliven the beast and define its form, while animal masks adorn the three legs and cloud patterns are incised on the surface of the burner. The Koryo potter excelled in producing small ceramic sculptures of animals and figures, as is demonstrated by an early twelfth-century water dropper in the shape of a duck (pl. 7). The bird seems to float placidly, holding 10 a lotus stem in its beak. The carefully modeled feathers are further detailed with fine incised lines. Celadons such as these reflect the enormous curiosity and interest that the Koryo potter had in the life and nature of the Korean countryside.

The excavation of the tomb of King Injong, who died in 1146, was one of the most significant of all excavations relating to the history of Koryo ceramics. There, celadon vases of superlative quality were unearthed, attesting to the extraordinary quality of the ceramics of this period. Although the melonshaped lobed vase discovered among these may derive its form from Chinese Qing-bai models, its flawless execution and aesthetic ambience is typically Koryo (pl. 8). The stately, lobed body of this vase is supported by a pleated foot, and the mouth emerges with the graceful petals of a morning-glory. The smooth glaze is exquisite, and has the tone of a warm, liquid green. Fragments of similar vessels have been found at the Sadang-ni kiln site in Kangjin.

|

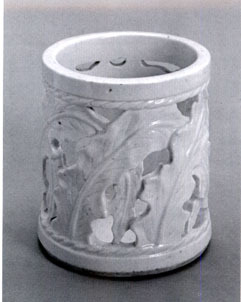

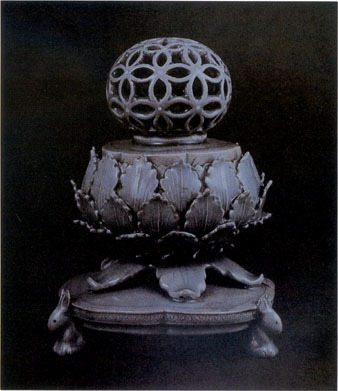

One of the novel features of Koryo celadons is a preference for reticulated openwork, such as that often found on incense burners (pl. 9). A beautiful burner in the National Museum of Korea is supported by three charmingly obedient rabbits who support an assemblage of gracefully modeled leaves appliqued to a central pod. A ball atop the container is intricately rendered with interlocking circles in openwork. Tea-drinking was a popular social custom during the Koryo period and, at first, Chinese Yueh teabowls were preferred because of their jade-like color and elegant shapes. By the twelfth century, however, many handsome tea-cups, bowls, and ewers were being created in Korea. Typical of these is an elegant ewer that was subtly modeled in the shape of a bamboo stem, with delicately incised details (pl. 10). The supreme invention of the Koryo potter was the use of black and white inlaid design. It is exemplified by a handsome maebyong vase with an inlaid design of cranes flying amid mushroom-shped clouds (pl. 11). The technique of inlaying seems to have been invented around the middle of the twelfth century. Xu Jing's memoirs of 1123 make no mention of inlaid designs; nor did the tomb of King Injong, who died in 1146, yield any specimens of inlaid celadons. However, the tomb of King Mun Yu, who died (3-3, p. 11) in 1159, did contain examples of Koryo inlay. The process of inlaying designs in celadons is complex. The design must initially be incised from the leather-hard clay body. The recessed design is then filled by brushing in a white or reddishbrown clay, and the piece is fired at 900 degrees centigrade. This baked biscuit is then covered with a transparent celadon glaze and, after a second firing at 1,300 degrees centigrade, the reddish-brown clay appears black. In some Koryo vessels only white clay was used, while in others the background was cut out and inlaid to create a reverse inlay. Although the black and white sgraffiato slip designs of Chinese Cizhou wares may have been one of the sources of the Koryo inlay technique, the incised and stamped patterns on Old Silla and Unified Silla grey wares suggest that there were also Korean antecedents. |

|

Another unique innovation of the Koryo potter was the use of a copper oxide underglaze, which produced red designs when fired under reduction conditions. The earliest use of this technique occurred during the first half of the twelfth century, as exemplified by a celadon bowl with floral arabesques in underglaze copper oxide, now preserved in the British Museum. By the late twelfth century — and throughout the thirteenth century — copper oxide was frequently used to create colorful accents on inlaid celadons. Considering that cultural exchanges are usually reciprocal, it is interesting that Chinese potters did not begin to use copper oxide underglaze until the Yuan period, at the end of the thirteenth century.

|

Loss of Momentum By the beginning of the thirteenth century, the richest period in the development of Koryo celadons had ended. Aesthetic inspiration lost momentum, and decline set in. The excavation of later Koryo kiln sites confirm!s this. The ceramic kiln complex at Mudungsan near Kwangju, for instance, is known to have been active during the transitional period between the late Koryo and early Yi dynasties /that is, from the mid fourteenth to mid fifteenth centuries. In 1962 this site was excavated, revealing celadon sherds of poor quality, inlaid with repetitive stamped patterns. Inlaid designs had become overly profuse, bold, and pretentious, and their execution lacked technical skill and grace. In addition, firing techniques had deteriorated: underglaze iron painted designs — a relatively unsophisticated technique in use as early as the eleventh century — had become the common medium. A maebyong jar inscribed with the date 1345 provides eloquent testimony to this decline (pl. 12). A Rare Moment The artistic efflorescence and splendor of twelfth-century Koryo celadons is a wondrous historical phenomenon. Korean potters had spent nearly two centuries under the tutelage of Chinese and Liao potters, perfecting their skill in the creation of celadons. By the end of the eleventh century, many excellent celadon wares had been import!ed to Korea from Ding and other northern Chinese sites, and a number of these were subsequently interred in Koryo tombs. Emigrant potters from Liao, who sought refuge in Korea between 1115 and 1117, brought with them still another ceramic tradition. Magnificent examples of Chinese Imperial Ru wares — created for Emperor Hui-zong (Hui-tsung) during the first quarter of the twelfth century — arrived in Korea as a result of exchanges between the ruling |