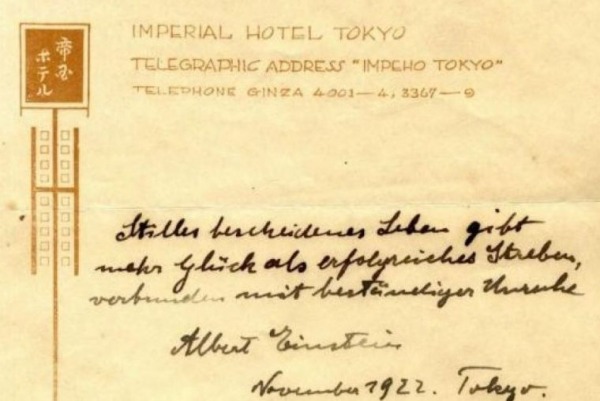

1922. 강연투어 중 노벨상 수상결정 소식을 듣고 일본 도쿄 제국호텔 벨보이에게 팁 대신 준 자필 메모

2017. 10. 24. 이스라엘의 경매에서 약 20억 원에 낙찰

Stilles bescheidenes Leben gibt mehr Glück als erfolgreiches Streben,

verbunden mit beständiger Unruhe.

조용하고 검소한 생활이 끊임없는 불안에 묶인 성공을 추구하는 것보다 더 많은 기쁨을 준다.

Wo ein Wille ist, da ist auch ein Weg.

뜻 있는 곳에 길이 있다.

He is known as one of the great minds in 20th-century science. But this week, Albert Einstein is making headlines for his advice on how to live a happy life — and a tip that paid off.

In November 1922, Einstein was traveling from Europe to Japan for a lecture series for which he was paid 2,000 pounds by his Japanese publisher and hosts, according to Walter Isaacson’s biography, “Einstein: His Life and Universe.” During the journey, the 43-year-old learned he’d been awarded his field’s highest prize: the Nobel Prize in physics. The award recognized his contributions to theoretical physics.

News of Einstein’s arrival spread quickly through Japan, and thousands of people flocked to catch a glimpse of the Nobel laureate. Impressed but also embarrassed by the publicity, Einstein tried to write down his thoughts and feelings from his secluded room at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

That’s when the messenger arrived with a delivery. He either “refused to accept a tip, in line with local practice, or Einstein had no small change available,” according to the AFP.

Instead, Einstein wrote two short notes and handed them to the messenger. If you are lucky, the notes themselves will someday be worth more than some spare change, Einstein said, according to the seller of the letters, a resident of Hamburg, Germany who is reported to be a relative of the messenger.

Those autographed notes, in which Einstein offered his thoughts on how to live a happy and fulfilling life, sold at a Jerusalem auction house Tuesday for a combined $1.8 million.

“A calm and modest life brings more happiness than the pursuit of success combined with constant restlessness,” reads one of the notes, written in German on the hotel’s stationery.

It just sold for $1.56 million. The letter had originally been estimated to sell for between $5,000 and $8,000, according to the Winner’s Auctions and Exhibitions website.

Gal Wiener, chief executive of the auction house, said the bidding on that note began at $2,000 and escalated for about 25 minutes, the Associated Press reported.

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” read the other note, written on a blank sheet of paper. That note sold at auction for $240,000 and was initially estimated to sell for a high of $6,000.

Neither the buyer’s nor the seller’s identity has been made public.

Roni Grosz, the archivist overseeing the Einstein archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told the AFP that the notes help uncover the innermost thoughts of a scholar whose public profile was synonymous with scientific genius.

“What we’re doing here is painting the portrait of Einstein — the man, the scientist, his effect on the world — through his writings,” Grosz said. “This is a stone in the mosaic.”

Einstein was among the founders of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and gave the university’s first scientific lecture in 1923. He willed his personal archives, as well as the rights to his works, to the institution.

Back in 1922, Einstein six-week tour of Japan was a huge success.

Einstein was still traveling during the Nobel award ceremony in December 1922, so he was absent when the chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics said that “there is probably no physicist living today whose name has become so widely known as that of Albert Einstein.”

Perhaps Einstein would have settled for something more “calm and modest.”

The year 1922 was a busy one for Albert Einstein: He completed his first paper on unified field theory, went to Paris to help normalize French-German relations and joined an intellectuals committee at the League of Nations.

Shortly before heading to Asia for a lecture tour, he learned that he had won the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics. But rather than head to Stockholm for the award ceremony, he decided to keep his plans and continued to Japan.

When he arrived in Tokyo, thousands greeted him at the Imperial Palace to witness his meeting the emperor and empress, according to Walter Isaacson's biography of Einstein. Nearly 2,500 paid to see his first lecture in the city, which lasted almost four hours with translation.

"No living person deserves this sort of reception," he told his wife, Elsa, amused at the throngs who waited outside his hotel balcony in hopes of catching a glimpse of him. "I'm afraid we're swindlers. We'll end up in prison yet."

While staying at Tokyo's Imperial Hotel, a courier came to the door to make a delivery. The courier either refused a tip or Einstein had no small change, but Einstein wanted to give the messenger something nonetheless.

So on a piece of hotel stationery, Einstein wrote in German his theory of happiness:

"A calm and modest life brings more happiness than the pursuit of success combined with constant restlessness."

On a second sheet, he wrote another message: "Where there's a will there's a way."

He told the bellhop to save the notes — they just might be valuable in the future.

And indeed they were.

In an auction in Jerusalem on Tuesday, the note on happiness sold to an anonymous European bidder for $1.56 million. The second note fetched $240,000.

A spokesman for the auction house, Meni Chadad, told The New York Times that it had expected the notes would garner $5,000 to $8,000. When the sale was announced, he said, the room burst into applause.

"It was an all-time record for an auction of a document in Israel, and it was just wow, wow, wow," Chadad said. "I think the value can be explained by the fact that the story behind the tip is so uplifting and inspiring, and because Einstein continues to be a global rock star long after his death."

Don't have a million dollars? Einstein's papers are archived at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he was a founder and member of the board.

More than 2,000 of his papers have been digitized for online perusal, including his handwritten theory of relativity, a diary of his 1930-31 trip to the U.S., and the manuscript for an article titled "E=mc 2 : The Most Urgent Problem of Our Time."

There are also his notes from lectures he was giving on general relativity in Berlin and Zurich in 1918-19. In an entry from Nov. 9, 1918, the day that German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated the throne, Einstein wrote: "[Lecture] cancelled due to revolution."

The seller of the Imperial Hotel notes is reportedly a grandson of the Japanese bellboy's brother who lives in Germany.

It turns out Einstein's theory of valuation was right on the money: "They are very, very happy," Chadad told the Times.

"Bescheidenes Leben gibt mehr Glück als erfolgreiches Streben"

1922 steckte Albert Einstein einem Hotel-Dienstboten in Tokio zwei handschriftliche Botschaften zu. Nun wurden die Sinnsprüche versteigert - für ein Vielfaches des Schätzpreises von ein paar Tausend Dollar.

Ein handschriftlicher Sinnspruch von Physik-Genie Albert Einstein ist für 1,56 Millionen Dollar versteigert worden. Ein Europäer erstand den Zettel bei der Auktion in Jerusalem, wie das Auktionshaus Winner's mitteilte. Der Käufer wollte anonym bleiben.

Der Zettel erzielte ein Vielfaches des Schätzpreises von 5000 bis 8000 Dollar. Das Bieten begann bei einem Preis von 2000 Dollar, es endete etwa 25 Minuten später bei dem Millionenbetrag.

Einstein hatte dem Dienstboten 1922 im Hotel Imperial in Tokio während einer Vortragsreise zwei Botschaften zugesteckt. Die zweite wurde ebenfalls versteigert, sie lautet: "Wo ein Wille ist, da ist auch ein Weg." Der neue Eigentümer dieses Zettels zahlte mehr als 200.000 Dollar.

Laut dem Verkäufer der Botschaften, einem in Hamburg lebenden Verwandten des Dienstboten, soll Einstein diesem weise vorausgesagt haben, die Zettel könnten irgendwann weitaus wertvoller als ein einfaches Trinkgeld sein.