어깨 관절의 불안정성에 관한논문

![]() Shoulder Instability. management and rehabilitation.pdf

Shoulder Instability. management and rehabilitation.pdf

abstract

Shoulder dislocation and subluxation occurs frequently in athletes with peaks in the second and sixth decades. The majority (98%) of traumatic dislocations are in the anterior direction. The most frequent complication of shoulder dislocation is recurrence, a complication that occurs much more frequently in the adolescent population. The static (predominantly capsuloligamentous and labral) and dynamic (neuromuscular) restraints to shoulder instability are now well defined. Rehabilitation aims to enhance the dynamic muscular and proprioceptive restraints to shoulder instability. This paper reviews the nonoperative treatment and the postoperative management of patients with various classifications of shoulder instability.

- 운동선수의 어깨 탈구, 아탈구는 20대, 60대에 가장 많이 발생. 98%에서 ant direction으로 타박에 의한 탈구.

- 어깨 탈구의 흔한 합병증은 반복재발

- 어깨불안정성에 정적( capsuloligamentous and labral), 동적(neuromuscular) 제한은 잘 정의되어 있음

- 재활치료의 목표는 어깨불안정성에 dynamic muscular and proprioceptive restraints을 증진시키는 것

Shoulder stability is the result of a complex interaction between static and dynamic shoulder restraints. Disruption to these restraints manifests itself in a spectrum of clinical pathologies ranging from subtle subluxation to shoulder dislocation. This article describes the anatomical variants associated with both traumatic and atraumatic shoulder instability and evaluates existing literature pertaining to nonoperative and surgical management with the ultimate aim of providing guidelines for the rehabilitation of various classifications of shoulder instability.

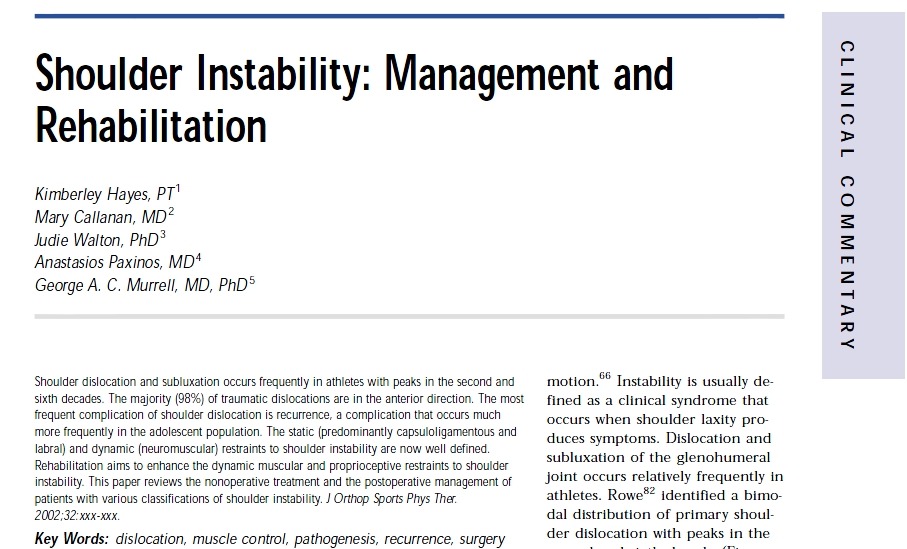

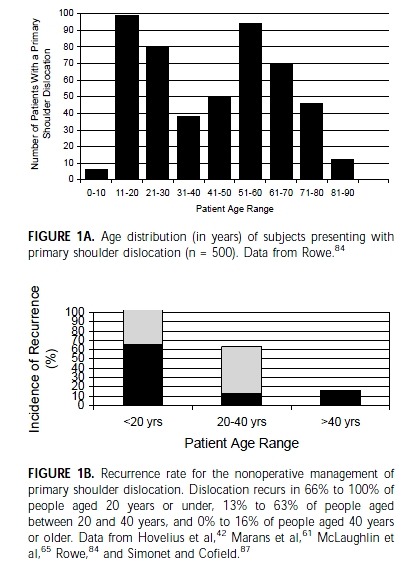

Primary dislocation

- 20대와 60대에 가장 많이 발생

- 95%에서 trauma가 원인. 98%가 ant direction.

- 5%에서 atraumatic origin. 원인은 capsular laxity or altered muscle control of the shoulder complex.

Recurrent dislocation.

- primary dislocation의 중요한 합병증은 recurrent dislocation. 2년이내에 대개 다시 탈구가 발생.

- 재탈구는 대개 나이가 들어감에 따라 탈구는 줄어들고 젊은 경우 탈구가 많음.

Functional Anatomy and Biomechanics

Static shoulder restraints refer to the bony ball and socket configuration of the shoulder and the major soft tissues holding these bones together. The soft tissues include the capsule, the glenohumeral ligaments and the glenoid labrum. Dynamic shoulder restraints refer to the neuromuscular system, including proprioceptive mechanisms and the scapular and humeral muscles.

Static Stabilizers

While the shoulder joint surfaces are highly congruent,89 there is minimal bony containment of the humeral head in the glenoid cavity. At most, only 25% of the humeral head is in contact with the glenoid fossa in any given shoulder position. 13 Under normal circumstances the shoulder capsule is relatively large and loose.19

- shoulder joint surfaces가 가장 적합할때, glenoid cavity에 humeral head의 bony 견제가 최소로 존재

- humeral head의 오직 25%가 glenoid fossa에 접촉. 정상적인 상황에서 shoulder capsule은 상대적으로 크고, loose함.

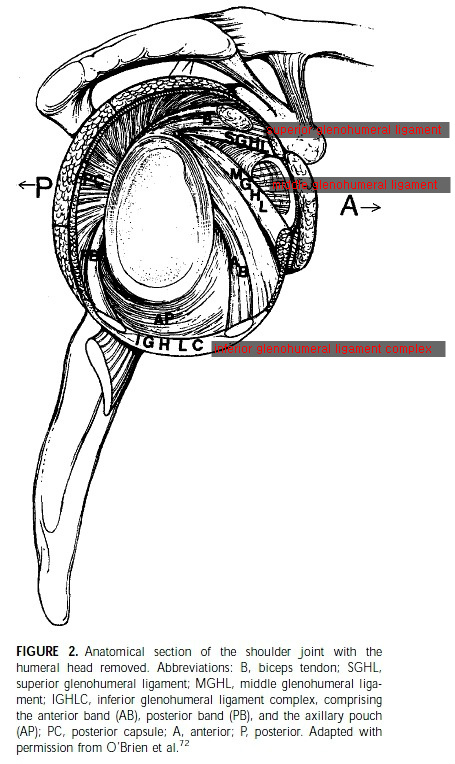

The discrete thickenings or capsular ligaments of the capsule have been named the superior glenohumeral ligament (SGHL), the middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL), and the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex (IGHLC) (Figure 2).72 The relative contributions of the capsuloligamentous restraints to stability of the glenohumeral joint are variable.

어깨 인대의 기능

1) The SGHL primarily limits anterior and inferior translation of the adducted humerus.15,72

2) The MGHL primarily limits anterior translation in the lower and middle ranges of abduction.15,72

3) The IGHLC is the longest and strongest of the glenohumeral ligaments85 and has been identified as the primary static restraint against anterior, posterior, and inferior translations when the humerus is abducted beyond 45°.72

The labrum constitutes the fibrocartilagenous rim of the glenoid. Inferiorly it is firmly attached to the glenoid, although it may be loose and mobile anterosuperiorly. Although variable in size, the labrum contributes to shoulder stability by increasing the depth of the glenoid cavity from an average of 4.5 to 9.0 mm in the superior-inferior direction and from an average of 2.5 to 5.0 mm in the anteriorposterior direction.43 The labrum may also act as a chock block(멈추개), having been shown to increase resistance to glenohumeral translation by up to 20%.58,63 The labrum provides attachment of the glenohumeral ligaments anteriorly, and the biceps tendon superiorly.

- 관절순은 glenoid의 fibrocartilagenous rim (섬유인대 림).

- 관절순은 위로는 상완이두근 건이 부착하고, 아래로는 glenohumeral ligament가 부착.

Dynamic Stabilizers

A number of dynamic EMG studies have shown that the rotator cuff works in a combined synergistic action to create a compressive force at the glenohumeral joint during shoulder movement.16,45,55 Radiographic evaluation of glenohumeral kinematics in the normal shoulder has shown that the center of the humeral head deviates from the center of the glenoid fossa by no more than an average of 0.3 mm throughout abduction in the plane of the scapula.22,79 With fatigue of the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles, there was an average 2.5 mm superior migration of the humeral head.22

- 회전근개 근육은 어깨 움직임 동안 GH joint에서 주요 작용을 함

- 회전근개(극상근, 극하근, 소원근, 대원근)와 삼각근의 근피로는 humeral head의 평균 2.5mm 상방이동

The biceps assist the rotator cuff in creating glenohumeral joint compression. In an abducted and externally rotated cadaveric shoulder model,46 static loading of the rotator cuff and biceps brachii muscle (long and short heads) significantly reduced the magnitude of simulated anterior humeral head translation. For conditions of increasing shoulder instability (vented capsule, simulated Bankart lesion) the biceps brachii made a greater contribution to shoulder stability than the individual muscles of the rotator cuff.46

- 상완이두근은 GH joint 압박력을 창조하는데 회전근개를 도움.

- 어깨관절의 불안정성이 증가된 상황에서 상완이두근은 회전근개보다 어깨관절의 안정성을 제공하는 역할을 함.

The individual tendons of the rotator cuff splay and interdigitate to form a wide, continuous insertion on the humeral tuberosities.23 Near their insertions, the deep surface of these tendons are tightly adherent to the underlying joint capsule.23,24 It has been hypothesized that contraction of the rotator cuff muscles may tighten the underlying capsule, creating a soft tissue barrier to excessive humeral head translation.104,105

EMG studies of shoulder kinematics have shown that the scapulothoracic muscles operate as functional units to create upward scapular rotation.9,45 Synchronous scapular rotation and humeral elevation is prerequisite for maintaining optimal alignment of the glenoid fossa and humeral head.45 Because there are no scapulothoracic ligamentous restraints, the

scapulothoracic muscles also serve to stabilize the scapula on the thorax. Stability of the scapula in relation to the moving upper extremity provides a secure platform for the glenohumeral articulation and the action of attaching humeral muscles.

- 근전도 검사에 의하면 scpulothoracic muscle은 견갑골의 upward rotation을 담당하는 기능적 단위가 됨.

- 조화로운 견갑골 회전과 상지 거상은 humeral head와 glenoid fossa의 최적의 정렬을 유지하는 전제조건임

- capulothoracic ligamentous restraints이 없기 때문에 scapulothoracic muscles은 흉곽에 견갑골을 안정화시키는 역할

It has been suggested that proprioceptive mechanisms involving reflexive muscular action may protect against excessive translations and rotations of the glenohumeral joint.100 A recent histological investigation97 has demonstrated the presence of mechanoreceptors (ruffinian corpuscles and pacinian corpuscles) within the capsuloligamentous restraints of

the shoulder. These specialized nerve endings relay afferent information relating to joint position and joint motion awareness (proprioception) to the central nervous system.

- 반사성 근육 활성과 관련된 고유수용성 기전은 GH joint의 과도한 이동과 회전을 방어하는 역할

The perceived sensation of shoulder joint position and movement is likely to play an important role in coordinating muscular tone and control. It has been suggested that joint instability secondary to trauma may be associated

with a decrease in proprioceptive reflexes and thus a predisposition to subsequent reinjury.97

- 어깨관절 위치감각과 운동감각은 근육톤과 조절을 coordinate하는데 중요한 역할.

Traumatic Anterior Dislocation

Mechanism of Injury The most common mechanism

of anterior shoulder dislocation has been described

as forced external rotation and abduction of the humerus

as seen in a basketball player who attempts to

block an overhead pass.5,59 Other mechanisms of injury

have included a fall onto an elevated outstretched

arm and direct force application to the

posterior aspect of the humeral head.5,59

Sequelae of Anterior Dislocation There are several

morphological changes associated with anterior dislocation

of the glenohumeral joint. The most significant

in terms of recurrent instability are those associated

with the inferior glenohumeral ligament

complex and its attachments to the labrum and humerus.

In 1923 Bankart8 described anterior labral

detachment as the essential lesion in traumatic anterior

instability (Figure 3). Rowe and Zarins84 noted

the lesion in 85% of traumatic instability cases requiring

surgery. An osseous Bankart defect on the

antero-inferior glenoid rim is best appreciated radiographically

with a West Point view.73 Detachment of

the anterior labrum and plastic deformation of the

capsule and inferior glenohumeral ligament complex10

contribute to increased anterior humeral

translation.44,90

The most common bony lesion associated with

traumatic glenohumeral instability is a compression

fracture at the posterolateral margin of the humeral

head. This occurs as the humeral head impacts into

the glenoid edge during dislocation and has been

termed the Hill Sach’s lesion.39 This lesion has been

reported to occur in over 80% of traumatic instability

cases21,73,99 and is best appreciated radiographically

with a Stryker Notch view and an

anteroposterior view with the shoulder in internal ㅜrotation.73 The lesion must involve more than 30%

of the proximal humeral articular surface to play a

significant role in recurrent instability.90 The lesion is

smaller than this in the majority of cases of traumatic

shoulder instability.83,99

Scapulothoracic motion asymmetry, as determined

by Moire topographic evaluation, has been found in

64% of patients with antero-inferior shoulder instability

compared to 18% of subjects with normal shoulders.

101 In 36% of patients with antero-inferior instability,

this asymmetry presented as scapular winging,

hence an increased anterior orientation of the

glenoid with repeated shoulder elevation. Simulated

glenoid anteversion in the abducted and externally

rotated shoulder has been shown to significantly increase

in situ strain of the anterior band of the inferior

glenohumeral ligament.102 Regardless of whether

scapulothoracic motion asymmetry represents a cause

or an effect of shoulder instability, suboptimal

glenohumeral joint alignment implies an increased

loading of surrounding capsuloligamentous restraints.

Proprioceptive deficits have been shown for patients

with traumatic anterior shoulder instability.88,10

Warner et al100 reported a significantly greater

threshold to detection of passive shoulder motion for

patients with shoulder instability compared to subjects

with normal shoulders (2.8° angular displacement

versus 1.9° angular displacement before detection

of passive shoulder motion). Reproduction of a

joint reference position was also significantly less accurate

for subjects with shoulder instability.100 Interestingly,

in this same study, a third group of test subjects

who had undergone arthroscopic or open

Bankart repair demonstrated normal proprioceptive

function for both of the variables examined.

Capsulolabral integrity may thus be important for

normal proprioceptive function.

Age-Related Changes

The high incidence of recurrent shoulder dislocation

in the adolescent population as opposed to recurrence

in those over 40 years of age may be explained,

in part, by the collagen profile of

encapsulating shoulder tissues. Collagen is the major

protein of ligaments and tendons. In newborns,

soluble collagen (type III) is synthesized and the fibers

formed from collagen type III are supple and

elastic. With each passing decade, collagen-producing

cells make less soluble collagen and progressively

convert to synthesizing an insoluble, more stable type

I collagen (Figure 4). This form of collagen has sulfur

groups that have a high tendency to cross-link

and form bridges between the collagen filaments,

causing the fibers they comprise to be relatively

tough and nonelastic. This changing ratio of collagen

types I and III throughout the body is so reliable

that chronological age of an individual can be

determined by analyzing the collagen type III content

of a skin sample according to the following

equation:7 collagen type III (mg)/wet dermis

(gm) = 1.3e-Age/23.5. Thus, the higher content of

stretchy collagen in tendons and ligaments can help

to account for the observation that younger people

who have already had a dislocated shoulder are

much more prone to recurrent dislocation than

older people. Once excessively stretched, their capsule

and ligaments may be too loose to provide the

secure and stable shoulder support required for

maximum athletic performance.

Atraumatic Dislocation

A small group of patients dislocate or sublux their

shoulders with minimal force application or by putting

their arms into certain positions. Neer and Foster70

thought the pathological entity was a loose re-dundant inferior capsule and introduced the term

multidirectional instability. Multidirectional instability

is less often associated with a labral detachment or

Bankart lesion. The condition is associated with generalized

ligamentous laxity.3,70

The definitive etiology of atraumatic instability is

still not clear and it may be multifactorial. Current

etiological theories include suboptimal muscle control

for shoulder function, a deficiency in the rotator

cuff interval, and connective tissue abnormalities.

EMG analyses of shoulder motion have demonstrated

altered patterns of shoulder muscle activity

for patients with atraumatic anterior instability when

compared to normal subjects.56 Radiographic analyses

of glenohumeral kinematics in patients with

atraumatic multidirectional instability have demonstrated

an increase in humeral translation and a decrease

in upward rotation of the glenoid fossa for

scapular plane abduction when compared to normal

subjects.75 While these studies have shown a correlation

between abnormal shoulder muscle activity,

glenohumeral incongruence and scapulohumeral

motion asymmetry, it remains to be determined

whether these findings represent a cause or an effect

of atraumatic shoulder instability.

Clinical studies have documented an association

between the size of the rotator cuff interval (a defect

in the anterosuperior capsule between the superior

border of the subscapularis tendon and the anterior

margin of the supraspinatus tendon) and the

amount of anterior84 and inferior glenohumeral

translation.71 A biomechanical study using a

cadaveric shoulder model has confirmed the importance

of the anterosuperior capsule in preventing

inferior subluxation of the adducted shoulder.36 A

large rotator cuff interval has been viewed by some

authors as a possible causal mechanism in some cases

of atraumatic shoulder instability.

Rodeo et al81 analyzed the collagen and elastic fibers

in the shoulder capsule in patients with unidirectional

anterior instability, multidirectional instability

at primary surgery, multidirectional instability at

revision surgery, as compared to patients with no history

of instability. Skin analysis between these groups

demonstrated a significantly smaller mean collagen

fibril diameter in skin samples in the primary

multidirectional instability group compared with the

unidirectional anterior instability group. This suggests

the possibility of an underlying connective tissue

abnormality.

Acquired Shoulder Instability

Chronic stress associated with repetitive overhead

sports has been cited as a predisposing factor to anterior

shoulder instability.1,2,31,57 These athletes usually

perform activities such as throwing, volleyball,

and tennis, all of which require extreme external

rotation with the humerus abducted and extended in

the horizontal plane. A current hypothesis is that

repetitive glenohumeral capsular overload in this position

of extreme range of motion leads to gradual

attenuation of the antero-inferior static restraints,38,57

increased glenohumeral translation and a continuum

of shoulder pathology.57 On the basis of arthroscopic

observations, Kvitne and Jobe57 described a pattern

of injury in this athletic population that involved primary

instability and secondary subacromial impingement

or posterosuperior glenoid impingement of the

undersurface of the rotator cuff with the posterosuperior

glenoid rim. In a separate retrospective review

of arthroscopic findings for 61 throwing athletes,

Nakagawa et al69 reported anterior joint laxity

in 33% of patients, detachment of the superior

glenoid labrum in 51% of patients, posterior labral

injury in 80% of patients, and rotator cuff tears in

66% of patients. While this study confirmed the presence

of several different shoulder pathologies in this

athletic population, there was no correlation among

anterior joint laxity, superior or posterior labral injury,

and a rotator cuff tear.

Nonoperative Management of Dislocation

Traumatic Instability Various treatments, including

shoulder immobilization, activity restriction, and exercise

rehabilitation have been advocated in the

management of primary traumatic anterior shoulder

dislocation. While low recurrence rates have been

reported for this condition for conservatively managed

older patients, the prognosis for patients aged

20 years and younger is generally considered to be

poor.

In a prospective study of 257 patients (age range

12 to 40 years) with a primary traumatic anterior

shoulder dislocation, Hovelius et al42 found no difference

in redislocation rates between treatment with

early mobilization and treatment with 3 to 4 weeks of

immobilization. Regardless of the immobilization period,

redislocation occurred in 47% of patients aged

from 12 to 22 years, 34% of patients from 23 to 29

years, and 13% of patients aged from 30 to 40 years

for the 2-year duration of the study.

Other studies of primary traumatic anterior shoulder

dislocation performed retrospectively have found

no beneficial effect of immobilization of up to 6

weeks duration.61,87 In one study of 21 patients (age

range 4 to 16 years), 100% recurrence rates were

reported for immobilization periods that included 0,

4, and 6 weeks in duration.61 Another study of 116

patients (age range 14 to 96 years) reported an overall

redislocation rate of 33% with no difference in

recurrence for periods of immobilization between 0

and 6 weeks duration.87 In the same study, 82% of

athletes aged 30 years or younger sustained a

redislocation (all due to athletic injury) compared to

30% of nonathletes of similar ages. While the type or

length of shoulder immobilization had no influence on the rate of recurrence, significantly better results

were reported for patients aged 30 years or younger

with 6 to 8 weeks of activity restriction compared to

activity restriction of less than 6 weeks in duration

(resolution of symptomatic shoulder instability in

56% and 15% of patients, respectively).

Therefore, the literature does not support shoulder

immobilization with a traditional sling in the

nonoperative management of primary traumatic anterior

shoulder dislocation. In a recent study47 of 18

patients who underwent magnetic resonance imaging

between 1 and 60 days after traumatic anterior dislocation

(6 patients with a primary dislocation, 12 patients

with recurrent dislocation), better approximation

between the Bankart lesion and the glenoid

neck occurred with the humerus positioned in adduction

and external rotation as compared to that

which occurred with conventional immobilization in

a position of humeral adduction and internal rotation.

In support of this finding, a cadaveric shoulder

experiment37 involving similar humeral positions (adduction

and external rotation versus adduction and

internal rotation) and a simulated Bankart lesion,

demonstrated significantly greater contact force between

the detached glenoid labrum and the glenoid

neck with the arm in the externally rotated position.

Lack of capsulolabral and glenoid contact after

glenohumeral joint dislocation helps to explain the

observation in previous studies that the rate of recurrence

is not influenced by the method or duration

of shoulder immobilization.47

There have been few studies investigating outcomes

for exercise rehabilitation in the nonoperative

management of primary traumatic anterior shoulder

dislocation. In one prospective study6 of 20 male patients

(age range 18 to 22 years), Aronen and Regan

reported a return to unrestricted duty and sports

participation without redislocation for 75% of cases

with a rehabilitation program that emphasized

strengthening for the muscles of shoulder internal

rotation and adduction (mean follow-up of 35.8

months). Another study107 of 104 patients (mean age

± SD = 21.5 ± 8.5 years) reported a success rate of

83% with a 6-week graduated exercise regime of limited

abduction (mean follow-up of 156 months).

These studies support a role for activity restriction

and exercise rehabilitation in the nonoperative management

of primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation.

In a prospective randomized study54 involving 40

patients, aged 30 years or younger, with a primary

traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation, Kirkley et

al54 reported a 47% redislocation rate for a treatment

group that received 3 weeks of immobilization

followed by a supervised shoulder range of motion

and muscle strengthening regime (activity restriction

enforced for 4 months). In the same study, a

redislocation rate of 16% was reported for a treatment

group that received immediate arthroscopic

surgery followed by an identical immobilization and

rehabilitation regime (mean follow-up of 32

months). Another prospective study17 involving 29

shoulders with recurrent anterior shoulder instability

secondary to a previous dislocation demonstrated

good or excellent results (as determined by the

Rowe and Zarins grading system84) in only 7% of

cases with a rehabilitation program that emphasized

progressive strengthening of the rotator cuff, deltoid,

and scapular stabilizer muscles (mean follow-up of 46

months). Further research is warranted to clarify the

efficacy of exercise rehabilitation in the nonoperative

management of primary traumatic anterior shoulder

dislocation.

Atraumatic Instability As for traumatic instability,

there have been few investigations pertaining to exercise

rehabilitation in the nonoperative management

of atraumatic shoulder instability. In a prospective

study17 of 47 patients (age range 12 to 54 years) with

anterior, posterior, and multidirectional instability of

atraumatic origin, good or excellent results as determined

by the Rowe and Zarins grading system84 were

reported in 80% of cases with a rehabilitation program

that emphasized progressive strengthening of

the rotator cuff, deltoid, and scapular stabilizer

muscles (mean follow-up of 46 months). Shoulder

strengthening and coordination exercises combined

with lifestyle modification is the most commonly recommended

treatment for atraumatic instability.

17,60,70,103

There is much to learn about the best methods to

enhance compression of the humeral head on the

glenoid and to restore scapulothoracic motion symmetry

and proprioception to the unstable shoulder.

Most authors have acknowledged the importance of

strengthening exercises for all components of the

rotator cuff and deltoid as a means of controlling

glenohumeral translation. Infraspinatus and teres

minor strengthening exercises performed in higher

degrees of abduction have been advocated as a

means for reducing anterior glenohumeral ligamentous

strain during the throwing motion.18 Strengthening

exercises have also been advocated for the biceps

brachii as well as the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis

major, and teres major to enhance the stabilizing

action of the rotator cuff muscles at the

glenohumeral joint.27,46,78,104

Functional exercises that require coordination

among multiple muscle groups (eg, hitting a tennis

ball backhanded) have been recommended for retraining

normal patterns of muscle activity in the

patient with shoulder instability.27 In a pilot project80

involving nonoperative treatment of atraumatic anterior

shoulder instability, significant improvements in

work and sport function and pain intensity were reported

for a functional retraining program designed

to improve rotator cuff muscle control through the use of electromyographic biofeedback. Changes in

work and sport function and pain intensity were not

significant for a second rehabilitation program that

consisted of isokinetic resistance exercises designed

to improve shoulder muscle strength and endurance.

Various forms of scapular muscle retraining have

been advocated in the rehabilitation of shoulder instability.

27,53,105 These have included exercises designed

to stabilize the scapulothoracic articulation

(isometric exercises, manual stabilization techniques),

to restore normal patterns of scapular

muscle activity (upper extremity weight-bearing activities),

and to maximize scapulothoracic muscle

strength and endurance in preparation for a return

to normal functional use (resistance exercises,

plyometric exercises, sport-specific drills). It remains

to be determined whether scapular motion asymmetry

can be corrected with exercise rehabilitation in

the patient with shoulder instability.

The interplay between neural and muscular

mechanisms for dynamic glenohumeral joint stability

is incompletely understood. Inman45 theorized that

proprioceptive mechanisms were elicited as a result

of specific movement patterns rather than isolated

muscle actions. This theory would imply a role for

functional exercises that include positions of instability

to evoke reflexive muscular activity that may protect

against potential joint instability. Other forms of

neuromuscular re-education,27,104,105,106 including

joint repositioning tasks, proprioceptive

neuromuscular facilitation techniques, upper extremity

weight-bearing exercises, and plyometric exercises

have been used to retrain proprioceptive mechanisms.

Further research is needed to determine the

efficacy of these exercises in the rehabilitation of

shoulder instability.

Surgical Management

Traumatic Unidirectional Instability The most recent

and most successful surgical procedures for unidirectional

shoulder instability reattach the detached

labrum and associated glenohumeral ligaments with

little disruption to the length or attachment of other

structures around the shoulder (Bankart repair). An

open Bankart repair consists of detachment and later

reattachment of the humeral insertion of subscapularis

(or a split of the subscapularis) and a reattachment

of the labrum to the anterior glenoid with sutures

through bone or with suture anchors. Most

surgeons also reduce any capsular redundancy by

tightening the anterior capsule with sutures. Open

anterior stabilization is associated with a 12° loss of

external rotation of the shoulder, probably secondary

to shortening of the subscapularis tendon after

detachment-reattachment.34

Arthroscopic techniques for unidirectional

glenohumeral instability have been developed to reattach

the labrum without an open incision and without

subscapularis detachment. The reported

redislocation rates for arthroscopic anterior shoulder

stabilization are higher than those reported for open

procedures (2–18% versus 11%) (Table 1). However,

arthroscopic procedures are associated with less loss

in external rotation than open procedures.

Arthroscopic techniques for reattaching the labrum

can be divided into three categories: (1) a

transglenoid suture technique,14,26,35,51,62,74,76 (2)

arthroscopically delivered and tied suture anchors,

33,40,93 and (3) arthroscopically delivered biodegradable

tacs.4,12,25,26,28,51,52,86,92 A comparison of the

reported rates of recurrent dislocation for each technique

is made in the Table.

Multidirectional Instability The most commonly performed

and most successfully reported surgical procedure

for multidirectional instability of the shoulder

is an anterior capsular shift, an open procedure that

involves the overlaying and thus shortening of the

anterior and inferior capsule.3,60,77 Closure of the

capsular interval between the subscapularis and

supraspinatus has been reported to be successful in a

small series of patients with subluxation.30,36

More recently, capsular shrinkage has been advocated

as a treatment for more subtle cases of shoulder

instability. Thermal denaturation of collagen results

in uncoupling of the triple helices and

shortening of the collagen. A recent study noted a

15% to 40% reduction in length of a cadaveric

shoulder capsule subjected to 65°C to 72°C heat

(Figure 5).98 Also noted was an associated 15% loss

in load to failure properties. Arthroscopic devices

have been designed to deliver heat to the shoulder

capsule with the potential to ‘‘shrink’’ redundant

capsule arthroscopically. A short-term study has reported

excellent results using this technique.86 Further

long-term evaluations are necessary to identify

the technique, indications, and results of this novel

method of reducing capsular volume.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

The basic principles of nonoperative rehabilitation

for shoulder instability (restoration of glenohumeral

compression stability, scapulohumeral motion

synchrony, and proprioceptive mechanisms) apply

equally to postoperative patients. The specific content

of postoperative rehabilitation varies according

to the stabilization procedure performed, individual

pathology, and the activity level of the individual.

Anterior Stabilization

Cryotherapy Cryotherapy in the postoperative shoulder

(applied for 15-minute durations every 1 to 2 waking hours for the first 24 hours, and 4 to 6 times

daily for the ensuing 9 days) has been shown to significantly

decrease the frequency and intensity of

shoulder pain both at rest and during rehabilitation

as compared to no-cryotherapy conditions.91 We recommend

15 minutes of cryotherapy every second

hour for the first week after a stabilization procedure

and after every exercise session for the duration of

rehabilitation.

Activity Restriction The postoperative management

of anterior instability has typically involved a minimum

of 6 weeks of activity restriction to minimize

stress to healing structures. During this period of

limited upper extremity use, we recommend active

exercise of noninvolved joints (elbow, wrist, and

hand). In the case of the injured athlete, rehabilitation

also aims to maintain cardiovascular fitness and

lower limb and trunk muscle condition.

Isometric Exercise Isometric shoulder muscle exercises,

initially performed with the arm adducted by

the side of the body, provide a means for preventing

muscular inhibition during the period of activity restriction.

Isometric exercises for the scapulothoracic

muscles are commenced during the first postoperative

week. Isometric exercises for the humeral muscles are commenced during the second postoperative

week. Care is taken when performing isometric

internal rotation for the first 6 weeks following an

open Bankart repair, in which the subscapularis

muscle is detached and reattached, to prevent rupture

from its humeral insertion. We recommend

pain-free contractions of 3 to 5 seconds duration and

a minimum of 30 daily repetitions20,32,64 for all isometric

exercises.

Range of Motion Exercises Assisted shoulder exercises

initially performed within a limited range of motion

are designed to protect the surgical repair and prevent

adhesion formation in the early postoperative

period. These exercises are commenced during the

second postoperative week. External rotation range

of motion is limited to 30° (0° abduction) for the

first 4 postoperative weeks. Combined external rotation

and abduction range of motion is avoided for

the first 6 postoperative weeks. Assisted elevation is

initially performed in the plane of the scapula to

maximize humeral and glenoid congruency.50 The

absence of pain, apprehension, and abnormal movement

patterns with assisted exercise are prerequisite

for the progression to active range of motion exercise.

Rehabilitation aims to restore full active range

of motion by 12 weeks after arthroscopic29 and open

anterior stabilization.103

Scapulothoracic Muscle Retraining In addition to isometric

scapulothoracic muscle exercises, the first

postoperative week involves treatment for any

strength or flexibility deficits within the lumbar or

thoracic areas.53 Upper extremity weight-bearing exercises

that incorporate specific scapular movements

at glenohumeral angles of less than 60° elevation are

introduced during the third postoperative week.53

Light resistance exercises are commenced during the

fourth postoperative week. We emphasize retraining

for scapular protraction and retraction and advocate

multiple sets of up to 30 repetitions for exercises

that involve both concentric and eccentric modes of

contraction.

Dynamic scapulothoracic stability, scapulohumeral

motion synchrony, and an absence of pain and apprehension

for movements performed between 0°

and 90° elevation are prerequisite for further rehabilitation

progression. Once these goals have been

achieved, upper extremity weight-bearing exercises

are advanced to higher angles of elevation and

weight-bearing loads are increased (eg, press-ups,

push-ups, and quadruped exercises).53 The

scapulothoracic muscles are comprehensively conditioned

through the use of free weights,27,67 various

resistance machines27,53 (eg, rowing, upright rows,

and pull-downs, anterior to the frontal plane) and

training activities27,105,106 (eg, throwing movement

exercises, blocking and ball defense exercises, and

water-based exercises) designed to replicate stresses

that will be imposed upon the shoulder during functional

upper extremity use.

Rotator Cuff and Humeral Muscle Strengthening Exercises

Rotator cuff strengthening is commenced with

isometric exercises, as detailed above. Light resistance

exercises for the rotator cuff and biceps

brachii muscles are introduced during the fourth

postoperative week. (For open stabilization procedures

involving detachment or reattachment of the

subscapularis, resistance exercises for the

subscapularis muscle are introduced during the sixth

postoperative week). We advocate exercises that involve

both concentric and eccentric modes of contraction

initially performed at glenohumeral angles

of less than 45° elevation. We use the same range of

motion to commence strengthening of the latissimus

dorsi, pectoralis major, and teres major.

Dynamic control of the scapulothoracic and

glenohumeral joints and an absence of pain and apprehension

for movements performed between 0°

and 45° elevation are prerequisite for exercise progression

to higher angles of elevation. Rotator cuff

strengthening for higher angles of elevation includes

the use of Theraband27,105 (eg, internal and external

rotation), free weights11,49,94 (eg, prone horizontal

abduction with arm externally rotated and scapular

plane elevation), and training activities27,106 (eg, underarm,

side-arm, and overhead throwing or catching

exercises using balls of various weights and sizes).

Humeral muscle strengthening includes Theraband

exercises27 (eg, extension and adduction initiated

from 90° flexion and abduction, respectively), free

weights94 (scapular plane elevation with arm internally

rotated and horizontal abduction with arm internally

and externally rotated), press-ups,27,94 pushups,

48 and various weight machines.27

Proprioception In the latter stage of rehabilitation,

emphasis is given to functional exercises that prepare

the neuromuscular and cardiovascular systems for

the return to sports participation. We include activities

that require the coordination of multiple

muscles (eg, catching and throwing activities, racquet

and other batting activities, and goal defense activities)

to achieve the desired magnitude, duration, and

sequence of motor output for a given functional

task. These exercises initially use glenohumeral positions

that are least likely to provoke an instability

episode. An absence of symptoms and quality of

movement are fundamental prerequisites for exercise

progression to positions that maximally challenge the

dynamic shoulder restraints.

Stabilization for Multidirectional Instability: Special

Considerations

Postoperative rehabilitation for multidirectional

instability is characterized by activity restriction and

strict range of motion control. Care is taken to pre-vent overstretching of tightened capsular tissues, particularly

after thermal shrinkage procedures that induce

an initial decrease in collagen tensile

strength.95,98 We restrict axial loading of the upper

extremity for 6 weeks. For cases with an anterior

component of instability, we restrict external rotation

range of motion to 30° (0° abduction) for the first

4 postoperative weeks and avoid combined external

rotation and abduction range of motion for the first

6 postoperative weeks. For cases with a posterior

component of instability, we avoid combined flexion,

internal rotation, and horizontal adduction for the

first 6 postoperative weeks.

Glenohumeral and scapulothoracic muscle retraining

guidelines used in the postoperative management

of anterior instability are also appropriate for the

postoperative rehabilitation of multidirectional instability.

We advocate a more conservative approach to

the rate of rehabilitation progression after stabilization

procedure for multidirectional instability, as the

success of this condition may be more dependent

upon the restoration of normal shoulder muscle

function.

CONCLUSION

In summary, there have been significant advances

in methods to restore function in both unidirectional

and multidirectional shoulder instability.68

Biomechanical and anatomical studies have enhanced

our understanding of the mechanics of the

shoulder joint with implications for the management

and rehabilitation of shoulder instability. Further investigation

of the mechanisms responsible for dynamic

glenohumeral control will help to delineate

the optimal treatment for shoulder instability.